Comments

-

The Shoutbox should be abolishedWhat was that guy's name who took over PF just to transform it into a cesspool? — Metaphysician Undercover

Porat.

And whatever happened to that site, is it completely gone now? — Metaphysician Undercover

Gone, yes. -

The Shoutbox should be abolishedI never posted in the Shoutbox on old PF, nor did I pay any attention to the short story competitions. At the time it was philosophical discussion or nothing for me. Times change.

-

The Shoutbox should be abolishedIf I’m to have any anointed or divine status, I see myself as a low-level demiurge, but a bit more benevolent than that of the Gnostics. Following the fall of Paul, allegiance was transferred to the supreme God Plush, who is entirely indifferent and non-interventionist with respect to TPF.

Let’s not forget those who did not make it here in the first place, high quality contributors such as To Mega Therion (fierce but fair Leninist physicist) and Sheps (wishy-washy socialist). A few others made it across but dropped out quickly, perhaps feeling that the death of PF was a good time to break the habit.

@Hanover was indeed instrumental in making a success of this place. His immediate enthusiasm for the move was unexpected, and the fact that he didn’t become a moderator until weeks or months later must have been, and must remain, a source of deep bitterness. -

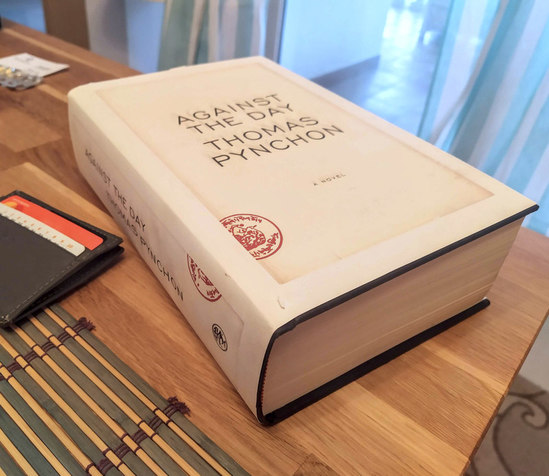

Currently ReadingI really hope you enjoy it [Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon]. I stopped at pg. 910 - no joke. Yes, I am that stupid — Manuel

I’m at around page 750 and while I do love it and think I’ll probably read it again, it’s so overwhelmingly maximalist and sometimes repetitive (almost repetitive in its endless inventiveness if that makes sense) that I’m getting tempted to skip sentences. And I’m forgetting some of the characters or getting them mixed up, maybe because they haven’t been fully drawn.

But it’s far too early to assess it. When I finished Inherent Vice my thoughts were not entirely positive but I’ve come to see it as top class, so I think these things take a while to digest. Although I get the feeling that AtD is indigestible first time around.

I shall plough on. -

Positive characteristics of FemalesThat's enough videos thanks. This isn't a platform for your campaign; it's a discussion.

-

What are you listening to right now?I'd have to say that Chick Corea/Return to Forever first got me into the jazz vicinity (i.e. fusion — busycuttingcrap

Oddly, for a long time the only fusion I really listened to was Weather Report. It’s only recently that I’ve begun to listen to Chick Corea/Return to Forever (which is even more weird because I went to see him in concert many years ago). I’ve been enjoying Romantic Warrior and The Leprechaun. The latter is total cheese but these days I can enjoy such things without shame. -

What are you listening to right now?That was the track that got me into jazz. To this day I never tire of it, which is more than I can say for some of the other stuff I was into at the time.

-

Kripke: Identity and NecessityI've been watching this and I've deleted a couple of posts by people who haven't addressed the article or who clearly haven't read it, but my skill in identifying them is limited to the obvious ones. Therefore, folks shouldn't hesitate to report off-topic posts.

-

How to hide a category from the main pageA sign of divergent and creative thinking or exemplary of a ubiquitous superficial preoccupation? — Banno

A bit of both, maybe?

Most importantly, it has allowed this notice to remain in or around the top of the main page, allowing all the active members to see it. -

Linguistic NihilismThere's a problem: All languages fail in re the purpose languages are assigned (thinking, communicating, etc.) — Agent Smith

Sometimes, but it doesn't mean you shouldn't keep trying, Agent Smith. -

If you were (a) God for a day, what would you do?a fantastical Culture style utopia — Captain Homicide

As in Iain M. Banks's Culture civilization, I take it? -

Currently ReadingI really hope you enjoy it. I stopped at pg. 910 - no joke. Yes, I am that stupid — Manuel

300 pages in and loving it. -

Do you feel like you're wasting your time being here?So, are you looking for higher quality content as per the OP? — Shawn

I would like to see more high quality stuff, such as more essay or book reading groups, like we did in the beginning. But I realize I’m not leading by example, as I hardly contribute to the philosophy discussions these days. Seems I could only keep that up for a few years. -

Currently ReadingYes, it does demand commitment, though as you say it's not all that difficult to read (if you don't mind long sentences).

Enjoy the journey. -

Currently ReadingISO...lost time — Pantagruel

Awesome box set.

Years ago I read the first two volumes but faltered in the third, which means I may have to begin at the beginning again if I want to read the whole thing (which I do). That's no bad thing, because those first two are excellent. -

Tarot cards. A valuable tool or mere hocus-pocus?I find both the Tarot and astrology interesting as providing a kind of vocabulary or system for thinking about aspects of human experience and personality. — bert1

Yes, exactly, it's an arbitrary frame, providing a kind of window on to one's life and mind.

I only came to appreciate this when someone I know, who had her own personal Indian astrologer, convinced me to do a consultation. I was impressed with the complexity of the charts he produced, and by his non-trivial insights and sometimes weirdly specific predictions and warnings. The real Indian astrology is so much deeper than anything I'd heard of before.

Of course, I don't believe in it at all, but it almost seems like that's missing the point.

And as Niels Bohr said of the horseshoe that was hanging in his house when asked if he really believed it brought good luck...

“No,” Bohr replied, “but I am told that they bring luck even to those who do not believe in them.”

(probably apocryphal, but it's a good one)

EDIT: One of the warnings was "do not take a long-distance car journey in the second half of 2022." -

"The wrong question"Am I reading to much into this? — bert1

I guess not, because despite what I said above, I have seen that attitude before around these parts. -

"The wrong question"I agree that it’s the height of bad manners for someone to say “you’re asking the wrong question,” without explaining what they mean.

However…

A question can be uninterpretable. It can be confusing. It can hide assumptions. It can be leading. But in what sense can it be wrong? — bert1

In the sense that the question already carries a view with it. Those hidden assumptions can indeed be wrong.

If your interlocutor explains this, as I think people here tend to do (correct me if I’m wrong), I think it’s fine. -

Recent post disappearedI deleted it, because it was just a YouTube link with a question along the lines of “what do you think?”

If you want to discuss a video, it's best to make some effort to summarize it, and tell us what you think of it yourself.

By the way, there is a Feedback category where you can post questions or complaints about moderation, so I've moved this there. -

Feature requestsYou can block posts by certain members using SophistiCat’s browser extension:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/5738/ignore-list-browser-extension/p1

But I’m afraid you’ll have to live with all the short stories popping up. It’s just once or twice a year. -

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?At first, when I saw they were dancing around, I was sceptical. But yeah, it works!

-

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?The only piece by Boulez that I really enjoy, probably because he abandoned serialism to do it. Rituel in Memoriam Bruno Maderna.

-

Currently ReadingI'd suggest V or GR before Against the Day. It can be a real possibility that this latter book will erode your endurance. It's not a bad book by any means, but it far inferior to V and GR. V is probably his most fun book. — Manuel

Thank you for this excellent advice, which I have decided to ignore. :grin: -

Currently ReadingJust read Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon. To begin with I found it a bit annoying, and even once I got into it I thought it was kind of forgettable and ephemeral. Then in the second half it became more involving, and now I've finished it I miss it. In any case it's a lot of fun and paints a picture of a world I knew little about (early seventies Los Angeles, the tail end of the hippie dream). So I'll give it the much-coveted :up: :sparkle:

Before I take on the monster that is his Against the Day, I'm currently reading Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov.

Jamal

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum