Comments

-

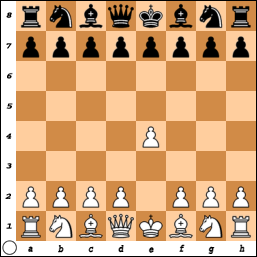

Friendly Game of ChessGood game.

Always down for another too -- I kind of like having the long play of a few days. Gives me something to warm my mind up on in the morning and set aside during the weekends without letting me forget. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoWhy would you assume that there needs to be an equality? The inequality is what the capitalist lives on, and it is the basic feature of relativism. — Metaphysician Undercover

The capitalist is the relativist: — Metaphysician Undercover

I feel like we're so close and so far away at the same time here.

There does not need to be an equality -- that's the false consciousness of the capitalist relativist. A capitalist says "A fair days work for a fair days wage", but the objective law of that wage is that the capitalist must pay the worker less than what they produce.

So the capitalist claims relativism but it's a narrow relativism that is, objectively, in the capitalist's favor.

Again, that's how I understand that section.

I want to note that there aren't so many demonstrations here (especially wrt Marx) as much as an introduction to the idea of ND -- we have much more of the book to go through is what I mean. We can drop this (as you note, usual) disagreement on interpretation and move on. -

Hate speech - a rhetorical pickaxeWhich is to say: Thought and feelings are already criminalized. I suppose if you don't say or do anything ever then no -- are you one to hold onto thoughts and feelings "outside" of what you do?

-

Hate speech - a rhetorical pickaxeI would too.

What I've noticed is that the law is invoked in various circumstances differently. "Free speech for me, but not for thee": anyone who speaks out of turn is punished by some other means by creatively interpreting the law to get rid of them -- or when the law is broken straight up lying to the judge who says "Sounds good to me" because he has to rely upon the police forces' testimony.

When the popo lie together that's where the weather goes. -

Hate speech - a rhetorical pickaxeLet us take an example:

"Kill all the white people!"

Substitute any group you wish. Suppose a person with influence yells that to their people wanting an answer for their problems.

Is that free speech?

If so then "free speech" is the right to say whatever you want to say even if it results in death.

The recent lynching of a black man in Mississippi is free speech under this definition -- it's only the person who pulled the rope that is guilty of murder. We should be free to sing songs of lynching people.

-

The Ballot or...Says the boy who tosses a snowball off a winter-kissed hill overlooking a remote village that is warned: "You shouldn't do that. It could cause an avalanche." — Outlander

But how would I know which way it'd go unless I toss? This is a relatively safe environment for exploring thoughts.

Also, to be technical. The last sentence is completely true. I would in fact relocate if I were him. Just to see what else is around, if nothing else. You're smart, but not very thorough. — Outlander

What I thought is untrue is that @frank didn't make "a genocidal statement" -- whatever the motive or result that's not what the statement does or is intended for.

It's important to me that "genocide" is understood in a fairly technical manner -- as well as "fascist"

Else it runs the risk of trivializing horrors I want to talk about and understand.

Glad to at least be "smart" ;)

I agree that I'm not thorough -- that's where things get hard. I like to pursue it but that's the hard part. And ultimately it's why I post threads like this: I don't know where I'll land at the end and that's why I wanted to talk about it.

This recent assassination compared to the ongoing genocide is what inspired the thought. There's certainly a contrast there in terms of exposure (the assassination) and impact (the genocide).

I don't think @frank was making a comment towards genocide or even something that'd result in genocide, but attempting to make light of a heavy situation. -

The Ballot or...This is a genocidal statement that would result in systemic discrimination, incarceration, enslavement, and eventual killing off of all those with relative small face-to-head ratios. You are the next Hitler and must be stopped. Nothing short of your immediate arrest will suffice. I would relocate somewhere else if I were you. — Outlander

None of that is true. -

The Ballot or...Voting is good. Supporting institutions as well as we can in relation to our capacities and opportunities is good. — Paine

I have to admit I was mocking voting in this retort. Mostly at the individual level -- i.e. if you're organized then voting can make a difference in some circumstances, but we don't live in a country where voting has much influence if you're just an individual voting in practical terms. That it exists influences conversations, but it's also well managed so that it doesn't influence policy.

One way I look at it is that MAGA has to reproduce to become a force in the next generation. If they completely "own the libs" the environment of the first generations will lose their meaning. Becoming a victim of one's own success does happen to people.

I'd say that's already there. Consider https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kyle_Rittenhouse -- the fascists have a multi-generational movement willing to utilize violence to purge the state of those unclean. That connections from the young to the old is part of why I say Trump has bloomed into full on fascism rather than the proto-fascism of yesteryears. They have enough people thinking like them that purifying the state with state powers are seen as legitimate uses of state power.

The illegals, the drug addicts, the unemployed, the disabled, the "antifa", the progressives, the atheists, the Muslims, the Jews, the anti-anythingTrumpsays-ers -- time to finally get rid of these dirty individuals so we can make ourselves great again. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoBut Adorno clearly says: "it can just as stringently be shown, however, why this objectively necessary consciousness is objectively false". — Metaphysician Undercover

I'd interpret this as it's the consciousness which is false rather than the necessary social law.

I'm interpreting Adorno as noting a performative contradiction in the relativist. The consciousness must adhere to the law of exchange, but if the entrepreneur were to do that then there is not an equality between labor-power and a wage unless the entrepreneur were to erase himself from the equation.

On one side we have the capitalist who sets the wage such that labor is reproduced and there is some surplus-value which said capitalist directs. On the other we have a worker who would set their wage equal to the value produced such that they keep their surplus value. Were the capitalist a true relativist then this social law could be mediated by people setting their own wages such that they retain their surplus-value.

But the capitalist is no relativist, after all -- there is only a very small part of thought which the capitalist relativizes, namely the Spirit and anything that has nothing to do with the productive process, such as the qualitative rather than the quantitative.

I could be wrong but that's how I understood that section, at least. -

The Ballot or...I'm sure if we register to vote this will all go away.

It's been ugly and getting uglier. I've admitted I didn't expect Trump 2.0 to go full fascist.

So what to do? -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoBy "Marxist Interpretation" I'm referring to Karl Marx more than latter political movements -- here the "objective law" I'm thinking is as Marx describes it in Capital.

-

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoAnd I do not understand what he means by this. What is "the objective law of social production"? — Metaphysician Undercover

The way I'm understanding that paragraph:

"... must calculate so that

the unpaid part of the yield of alienated labor falls to him as a profit,

and must think that like for like – labor-power versus its cost of

reproduction – is thereby exchanged"

is the law so described. "Like for like" is exchanged -- so a wage is set such that labor-power is sustained and reproduced and the wage is below the value being produced.

Ideologically "A fair days labor for a fair days pay" -- a falsity because if it were true then there'd be no profit, and thereby no entrepreneur. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoI think Adorno would say social process is equivalent to ideology. In that way, it is most distinct from Hegel's Absolute Spirit because Absolute Spirit thinks itself to have achieved objectivity. Negative Dialectics, on the other hand, is not a peering into reality, it is not truth through dialectic, rather it is a revelation about the presuppositions that sustain the ideological system. — NotAristotle

That gets along with what I'm thinking regarding @Metaphysician Undercover's inquiry.

At least insofar that we understand "Ideology" as more than "that which is thought", but something enacted and unquestioned. -

The Ballot or...A general note:

Analogies to family dynamics aren't good ways of understanding geo-politics if that's where we end. If that's what we have to work with then OK that's what we work with.

But political conflict is not a family dynamic. There are no "older siblings" or "Daddys". There is no such thing as an "immature" country from the political perspective such that another country can "guide" it. When a more developed country "guides" another there is always a realpolitik motive. The family analogies aren't helpful in understanding these sorts of relationships. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor AdornoNow the question is, what is the mentioned "objective law of social production". This appears to be the unifying principle of "social process", whereby the inspiration of commitment, causes the forfeiture of the distinct laws of the divergent perspectives, in favour of the objective law of "social production". — Metaphysician Undercover

I read that in a Marxist sense. So the entrepreneur must pay a wage which is below the value produced by the labor-power he employs, else he will not be an entrepreneur for long. "social process" I take it to mean "Capitalism" in the age he's writing in, but as Marx describes it. The "narrowness" of this relativism I took to mean that the bourgeois individualist who allows each of us to have our own truths is far more narrow than he presents -- the equality of labor to its wage is not questioned or relativized to the entrepreneur but is held as a truth that the laborer will have to follow whether they like it or not. So, in fact, we can't all just "have our own truth", at least in accord with this particular relativism, because there is one truth that we must insist upon -- which, more generally, I'd take from the Marxist notions to think about so the economic superstructure of some kind. -

The Ballot or...And yes -- I agree.

That seems part of the reflection, philosophically -- if you don't have a clear notion of both then how could you possibly choose? -

The Ballot or...We do not know what the killer had in mind. — Paine

Yes, and never will really -- I'm trying to make sense of things so posit various "motivations" that aren't really from evidence but an attempt to make sense of things.

The label "fascist" has been pinned to too many donkeys to form a shared idea.

I disagree in that I think it's a social phenomena worth identifying.

We have had experience of the MAGA version of our circumstances. Maybe they have been hoisted by their own petard. Maybe we will find out about that. Maybe not. — Paine

Yes, true.

What puzzles me about the MAGA message is to be told there is a war going on but also not a war. The absorption of 1/6 as a valid form of political expression versus preventing a hostile takeover by a particular cartel. — Paine

"Fascism" explains this, I'd say.

By contrast, I submit that John and Malcolm had a clear idea about the difference between war and peace. — Paine

John the Baptist? 4th book in the Bible?

The answer. -

The Ballot or...Yeah, but “how much violence we are already responsible for” is also a diversion. More fog. This is an easy one if you have any principles at all. — Fire Ologist

I did say that I don't believe he deserved what happened to him.

Charlie Kirk didn't deserve what happened to him in the sense that all he did made him worthy of punishment: But we're in a time when speakers of movements are legitimate targets for the propaganda by the deed. — Moliere

Now, granted, if all we're talking about is Charlie Kirk's assassination then it's a diversion.

I had a particular feeling in relation to his death, what he said, and our continued support for Israel.

And, ultimately, still feel fear at my own numbness.

Unless you really mean to ask: when should we be allowed to kill our political debate opponents?

No, not at all. I tend to see one-off assassinations as ineffective to what I want to achieve.

I'm asking after the justifications for political violence in a world where we condemn this sniper while living as we do. I genuinely don't get how Trump, for instance, can support Israel and condemn the sniper**.

**EDIT: I get it politically, but I mean the whole reaction that Trump joined in with: we condemn this random assassination as if we aren't supporting death on a mass scale elsewhere. In an ethical sense it shouldn't matter the laws, so much, as the deaths and how much they can be prevented. Sending weapons en masse without sanction isn't exactly on par with the reaction against this sniper.

We don’t get to bring a gun to a debate and have a debate. No one should celebrate what happened on any level. Charlie was as precious and loved as Malcom, and so many others.

That's the true Christian*** spirit I'm aware of.

I agree that no one should celebrate death -- that's the path to more death. It's part of why I'm disturbed at my own indifference, even though I can tell you why.

I've felt an absurd feeling I don't know how to describe succinctly since seeing that assassination and trying to contextualize it within what first came to mind. The thing that comes to mind for me is not only should we not celebrate, but we should pay attention to the death we're more directly involved in rather than continue the sensation. At least in light of the deaths we can prevent if we choose to act.

***EDIT: Given the circumstances I ought say the true Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Atheist spirit, and really all life and freedom loving people, but I succumbed to rhetorical devices. -

The Ballot or...Bingo.

It's the sort of logic that can lock one into a fight -- a tit-for-tat that lands on whichever side you want to favor. And usually adopted by the bully to try and confuse people as to who is really at fault.

In such a case we might look for an arbiter of some kind -- but I don't trust the United States in this matter.

I'd prefer the United Nation's ICC. -

The Ballot or...Jews lived alongside Hindus in peace for many centuries since neither group felt the need to convert or conquer the other — BitconnectCarlos

It would certainly be nice if those were the people we were talking about.

When one side refuses to accept the presence of the other, wars are launched, which lead to greater loss of land, more humiliation, and more victimization. It's a vicious cycle of victimhood.

After 10/7, Hamas lost its seat at the table. They shattered any prospective hope for peace. They acted like Nazis - summarily executing Israelis/Jews civilians and keeping Israelis/Jews in concentration camp-like conditions in captivity - and they deserve annihilation just like the Third Reich. Like the deaths of German civilians are ultimately the responsibility of the Third Reich, the deaths of Gazan civilians are on Hamas, as Israel takes considerable precautions to avoid disproportionate civilian deaths. — BitconnectCarlos

At least you aren't denying that it's a genocide -- you're just going about it saying that no matter what Israel does the presence of Hamas justifies everything that come.

I'm afraid that responsibility for death doesn't work that way, though. I'd welcome international trials once we disarm Israel -- but I'd put Israel on trial as the one responsible for the deaths of the people their army is killing, and not the dirty other that they must cleanse from the land.

As far as I'm concerned, it's Israel that has lost face in this exchange with their actions. It is they who have lost a seat at the table for free military aid: Look at what they do with it. They cry for people to remember Amulek, sow disinformation, speak duplicitously, and kill systematically such that they will destroy a people for voting for Hamas -- collective punishment -- and hopefully eliminate them from the land so they can take it for themselves.

But the United States isn't terribly concerned about the moral implications of all this -- they just want an airfield. So insofar that the elimination is contained to the Palestinians we'll continue sending military aid because almost no one in office opposes Israel, and people are punished for speaking up in favor of the Palestinian cause.

Which brings me back to my reflection on ballots and bullets: in the United States there is little the ballot will do regarding these matters. It is ineffective. What I see as peaceful means of opposition lies with BDS and the international community, though -- to use the bullet in the United States on this issue wouldn't be effective in spite of the lack of a ballot.

But for Hamas? Well, supposing you eliminate Hamas, given what's happened, were I to survive. . .

you cannot pass down hate and resentment about it from generation to generation. — BitconnectCarlos

This wouldn't be something you could shame me from. I'd be tempted to start Hamas 2.0 after seeing so many people slaughtered once you remove Hamas 1.0.

Which is why BDS strikes me as a moral giant. I don't think I'd have that restraint given what's happening. Hate and resentment will spread further and longer the further and longer the genocide continues. And just because Hamas was voted in that does not mean everyone within a territory gets to be killed because "they lost their seat at the table" for daring to fight back against apartheid. -

Reading group: Negative Dialectics by Theodor Adorno

I will try. I'm going to do a summary of each of the 5 paragraphs as I see it:

1. Dialectics is opposed to absolutism. Fundamental ontologists believe this is a relativism because of this, but ND is equally opposed to relativism as it is to absolutism. This attack on relativism is overdue because the previous retorts were unpersuasive enough that relativism could continue unabated. i.e. "Relativism presupposes an absolute" is a bad argument, and so relativism continues on, passing it over as an obvious palliative to the non-skeptical which doesn't consider the skeptics ability to negate without absolutes.

2. The first relativism is a bourgeois individualism: Everyone is endowed with rights, and thereby my truth is good for me and your truth is good for you given that we're all equal. This allows us all to keep our opinions to ourselves and go about the business of money and work: material relationships of the capitalist sort are preserved such that thought cannot broach them -- these are private, rather than public affairs, and everyone is free to think as they wish insofar that they work.

3. This can only be maintained in a sort of silence -- once consciousness comes to believe it has a truth thought no longer has a subjective contingency. I.e. relativism is undermined by our shared social reality of which we can cognize truths about. The individual thoughts could not come about without the objective conditions of society which found an individualistic society. "The strata-specific bounds of of objectivity..." are laid down by this sociology of knowledge. And the bourgeois individualistic relativist reveals themselves an objectivist in the sense that there is only one important thing: Where you fall in the pecking order of work, a truth that allows the individual to think their individual thoughts as long as they adhere to these economic forms.

4. Divergent perspectives have their truth in the social whole -- by cognizing this preestablished whole divergent perspectives lose what is non-committal. The capitalist must, lest he be eliminated in the social process, obtain a profit from his workers and treat the exchange of money for labor as an equality. So the individualistic relativism of the bourgeois entrepreneur can be revealed as objectively false, given the equality between wage and labor-power that he must assume, so he follows the objective process that follows from the private ownership of the means of production -- thus is revealed how narrow this skepticism is.

5. "The Perennial hostility to the spirit" I take to be referring relativism, but throughout all time rather than the bourgeois variety. It occurs because the concept of reason within existing relationships of production must fear that the trajectory of the emancipation of the concept of reason will disintegrate those very existing relationships of production -- we can live without the fetters of Church in our state, but not without the fetters of the private ownership of the means of production. "Here thought goes too far!" says our perennial relativist who depends upon Spirit being something outside of this relationship, something where my truth is mine and your truth is yours and we can get back to work.

This critique of relativism is a paradigm of determinant negation (in ND)

Yup that makes sense to me. -

The Ballot or...How can the Civil War be a war to you? The North didn't recognize the South as an independent country. — BitconnectCarlos

Does it matter? If you won't accept South Africa as an analogue, then ought I to accept the civil war?

I told you the differences I saw. I used South Africa because it's another colonial project.

With the States you have two colonial governments fighting. If I were to analogize something in the United States I'd say it's how we treated the Native Americans and Blacks rather than the Civil War. They were less than second class citizens, for the most part.

Tell that to the Israeli Arab muslims who serve in Parliament and as judges and professors with full rights. — BitconnectCarlos

What about the ones that don't have full rights?

Consider: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Israeli_citizenship_law#Status_of_Palestinian_Arabs

They were forced from their land and required to apply for citizenship with Israel and if they couldn't -- which most didn't -- they lost their property.

Technically speaking they're not citizens so it's not a "second class citizen" de jure -- but it is de facto.

I'm not entertaining this because Israel is not South Africa, nor has Israel begun bombing its own neighborhoods. Gaza is not an Israeli neighborhood or region. It is a territory possessed by an enemy political group. — BitconnectCarlos

Here's the part where Israel gets duplicitous. Prior to Oct 7th they wouldn't recognize their statehood. After Oct 7th they still won't recognize statehood, but they'll declare war on them as if they are a state. In times of peace they are controlled by the Israeli government, in times of war they're a fully independent nation.

Under apartheid they slowly drive out Palestinians with expansions of colonies. Under war they kill indiscriminately while holding a siege to keep people in an area where they can be slowly eliminated. This is all part of a history of slowly expanding and taking over Palestinian lands by any means necessary.

Drop the analogy if you wish. It was thinly veiled. The part that sticks, from my perspective, is that Israel effectively treats the Palestinian territories as an open air prison in "peace times", and a kill zone in "war times".

Keep in mind that over 10,000 rockets have been fired indiscriminately into Israel from Gaza since 10/7 and that 10-20% of these misfire and end up landing in Gaza itself. — BitconnectCarlos

... you realize that this comparison isn't in Israel's favor, yes?

In any case, whether we call it a war or a protracted conflict doesn't matter much to me... although near 1,000 Israeli soldiers have been killed since 10/7 but ultimately 'war' or 'protracted conflict' both fit.

My thought is that this is not a war, but a systematic erasure of another people for the purpose of obtaining land and punishing them en masse for voting for Hamas. I.e. a genocide.

Even if the Nazis were evil they kept Germany after the fact. Heidegger even got to stay a part of the party until it was legally dissolved. -

The Ballot or...So this genocide (oh, sorry, I mean ethnic cleansing) has nearly succeeded. A few thousand more dead babies (oops, I mean Hamas combatants) and destroyed buildings should do the trick over the next few years. All with the weapons and support of the US. — Mikie

Oh, I disagree there. It can still be stopped. There is still resistance. -

The Ballot or...That is different than hunting down and killing Hamas. I have no problem eliminating Hamas if it can be done without collateral damage or without the goal of stealing land. — RogueAI

Ehhh... given what we see right now, it really isn't possible to do that. This is what the Israeli government is pursuing in the name of routing out Hamas. -

The Ballot or...I often wonder how the normalization of violence figures into this sort of messaging. There is a blatant political device in particular instances such as pardoning all of the participants in 1/6. But that does not add up to a possible future. The whole theater is oddly barren. — Paine

I get the sense that the 4chaners et. al. just want to agitate people to kill others in order to cause a sense of terrorism. I don't think they care which side does it; what they care about is the terror, and the lack of culpability for themselves. They want to inspire others to carry out random acts of violence.

This is functionally speaking -- the ideology is hard to decipher, but that's on purpose. This is part of why I think of it as a fascist underground: fascists purposefully use duplicitous messaging with the intent of destroying social bonds with the state such that they can take over the state without a real political program other than hatred for the other, a desire for punishment, and the willingness to utilize the powers of state to carry out that mission.

Fascism is a cult that worships death for its own sake as a means to purify the population.

At least, that's my perception. It's terribly hard to track details on the actual people -- this is just what the part of the internet looks like that looks similar to what thus far this assassin at hand. -

The Ballot or...Meaning, both people would gladly perform the same acts upon one another, given the opportunity. It simply happens to be one who is able to instead of the other right now. — Outlander

While a penchant for violence is a part of human nature I do not think that people are sitting around waiting for their turn at the genocide stick. That's an entirely cynical view whereby we can dismiss any genocide on the basis that "Well, if the people who are being killed now had the opportunity, they'd be the genocidaires. So what's the difference? Let the genocide go on" -

The Ballot or...So the Civil War wasn't a war? Or the Revolutionary War, for that matter. — BitconnectCarlos

Naw, that's dumb.

There are significant differences between those and what's happening here, though, such that the "war" designation isn't exactly apparent to me.

Suppose South African Apartheid.

I see that situation as much closer to the situation in Israel -- Israel offers different rights to Jews than to non-News. Palestinians are segregated into different locations within the state of Israel. This is largely due to a desire for an ethno-state -- i.e. Arabs over there and Jews over here.

Suppose that South Africa, in response to a political act of terrorism on white people, set up artillery and began to systematically eliminate the Black neighborhoods in retaliation. Further suppose that they continued to bombard the schools, hospitals, journalists, civilian living quarters, universities, places of worship, etc. in the name of defeating the political group responsible -- how many non-combatants and places unrelated to combat can be purposefully annihilated before this stops being a "war" and starts being a "genocide"?

Part of me is also hesitant to describe this as a war on the sheer basis of firepower. If you hold a firing line to keep people within a place where you're going to bombard them regardless of their political orientation are we really engaging in war? Or is this Dresden extended over a longer period of time? Gaza is under siege while being bombarded. Part of the tools being used here are starvation to inflict mass punishment.

There are other means of genocide in play here too: if one targets people who have knowledge, such as doctors, journalists, teachers, scholars, holy persons, and legal authorities then it will be harder for the genocidaires to be persecuted -- if you destroy the evidence and the knowledge of a people then you can tell the story as you want. Consider "Go West Young Man" as a result of the United States' genocide.

So my theory of war needs refinement, but I don't see an apt comparison to either the United States' civil war or its revolutionary war. -

The Ballot or...If the destruction of Nazi Germany is genocide then nothing is genocide. — RogueAI

That's not what happened. There was a war between different powers and people were tried after a government surrendered. The destruction of "Nazi Germany" is not the same as the systematic hunting down of anyone associated with "Hamas" to the point that it's OK to kill unarmed civilians and topple down Hospitals or civilian living quarters or stop aid from coming in to starve out anyone that might be associated in order to take over the land.

Hamas isn't the fascist in this scenario -- they're not really a "liberal democracy", but they're not "Nazi Germany" -- not even close. -

The Ballot or...There's one thing here that I think is important to distinguish: this is not a war.

A war is between two countries that recognize one another.

Israel uses the UN definition to declare war on Hamas, but when they controlled the occupied territories they applied two levels of citizenship and deeply controlled who got in or out of the West Bank or Gaza.

It's not like Hamas just decided to be evil. There are reasons for why they were voted for that lead up to Oct 7th.

So as long as they "obey" the restrictions that continued to expand settlements they would not be bombed, but they weren't citizens of Israel as much as an apartheid. -

The Ballot or...When a Hamas terrorist dies, the world is improved. — BitconnectCarlos

I disagree.

That'd count as an example of "genocide": MW: "the deliberate and systematic destruction of a racial, political, or cultural group"

Hamas is a political group.

Something like "When a Republican dies the world is improved" would fit here.

Or even "When a Nazi dies the world is improved"

Only the Nazis did the genocide, so it is false to lament the death of a Nazi.

Whereas here we have the IDF carrying out the deliberate and systematic destruction of Hamas while killing anyone that gets in their way.

They don't use nukes because they want the land, not because they have restraint.

They don't use airpower because the land is close enough that artillery does the job.

It's not restraint -- it's systematic.

Moliere

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum