Comments

-

Bernardo Kastrup?The hypothetical question 'if a tree falls in the forest' is another way of posing the question and is often used to stimulate discussion on this very topic. It is a 'thought experiment' in philosophy, and again, not a question answerable by physics. — Wayfarer

If it's the same, then what is the point in referencing QM? What does that add to the thought experiment?

But if you say flat-out, outright, that 'philosophical idealism is not relevant to the issues raised by quantum mechanics', then you'd be mistaken. — Wayfarer

As far as the arguments I see being offered I'd say that this is the appropriate conclusion. A conclusion which may be modified in light of more argument, but I see no good reason to believe that QM implies idealism. It seems to me to remain entirely open, and I suspect ultimately unresolvable by QM. I'll just note real quick here that this is a separate issue from the notion of "observer" in QM though.

There may be more choices, but Heisenberg chose 'Plato and Democritus' as representative of idealism and materialism, respectively — Wayfarer

And there are more options than idealism vs. materialism. Personally I don't believe either are the case. That's the error Heisenberg is making.

A master, a brilliant mind, but just as human as you or I. It's not like he's alone in making said error. I've made the exact same error before, and probably will again.

But surely you understand that there's more options? It's not like by disproving materialism we suddenly gain idealism, or vice-versa.

The second point is that what is at stake, again, is the notion of an independently-existing, real, physical entity, the 'point-particle' that acts as a 'building block of reality'. The reason this is a vexed question at all, is because of that. The question is, what is the nature of reality? That's why it's a philosophical issue. — Wayfarer

I don't think I'm disagreeing with any of this. I agree it is a philosophical issue. I agree that these points are debated by Bohr and Einstein.

Where I disagree is that the double slit experiment, and use of the word "observer", implies idealism. That's the specific misreading I'm getting at. It's OK to have misread. I certainly do, and have misread on this very topic. It's complicated after all, yeah?

On a second point unrelated to the misreading, I just don't see a good argument to believe that idealism is implied by QM. For what it's worth, I don't think physicalism is implied either. I simply do not think either are implied. But that's the other disagreement that requires some kind of commitment to the knowledge.

Which brings me to a very simple question I've asked --

In order to reasonably infer what some bit of knowledge implies, we must first know that bit of knowledge. yes or no?

I'm not being rhetorical here. I would answer "Yes". And I would even say we can acquire said knowledge sans-certification. But it seems to me that this is a sticking point between ourselves.

So the point here is that this is a philosophy that explicitly accepts that 'the subject' has a role, is part of the landscape. Whereas, the whole conceit of a lot of science is that things are seen from a viewpoint of ultimate objectivity — Wayfarer

Isn't this here specifically what concerns you?

You believe the subject has a role in the world. You also believe that certain widespread conceits of science eliminate said subject. So you prefer to present and express scientists who do not, by your view, express that conceit.

I don't have a problem with biases like this. Everyone has them. But it is a problem when said biases get in the way of understanding what's actually being said, such as the case of the observer being interpreted as a mind causing an outcome, because then we're no longer talking about knowledge.

That is important, isn't it? Not rhetorical. I'm looking for that common ground upon which disagreement can take place. You do care that some bit of knowledge is true, don't you? And must we actually understand some knowledge in order to reasonably infer implications from it? -

Bernardo Kastrup?The role of observation in determining an outcome - not by 'interfering with' or physically causing an effect, but simply observing. It seems to implicate the mind of the observer. — Wayfarer

So in what way is this example any different than, say, that of a tree falling in a forest?

Because the word "observe" you use here really does mean something different, as SX pointed out. "observation from a mind determines the outcome" is not what's being said.

I underlined that phrase as to whether 'they exist in the same way' as ordinary objects, because I think it's important. And overall, I think it's fair to say that Heisenberg's attitude to the philosophy of physics favoured some form of idealist philosophy, as did some (but not all) of his peers. — Wayfarer

He did, yes. But here's the mistake in the quote -- there are more options than between Democritus and Plato. We don't have two choices, either Democritus or Plato, between which we must choose. There are more options. We are even free to create our own.

Also this still doesn't relate to a notion of "observer" as you are using the word. It's not just that there is a mind passively observing which causes an outcome, therefore Plato. Heisenberg had some idealist notions as did Bohr about the world. But that doesn't mean that QM automatically implies idealism, either. We don't have to bow before the masters and follow them in everything they believed. We are right to ask why they came to their conclusions.

Put it this way, I try to remain aware of my limitations, which are considerable — Wayfarer

That's not exactly answering my question.

Before we can reasonably infer what some bit of knowledge implies, we must first know that bit of knowledge. Yes or no? -

Bernardo Kastrup?So - the ‘ontological implications’ of this are what was at issue in the debates between Bohr and Einstein. It’s all about what is really there, prior to it being measured. Is it a wave or a particle? Is it in a particular place? I think the so-called ‘copenhagen’ view is that there is no ‘it’ until it is measured. And that’s why it has a philosophical dimension: we’re purportedly debating the most fundamental reality, and yet can’t say what it is independent of the act of measuring it. — Wayfarer

I don't deny that there is a philosophical dimension. Heck, I don't think there's a reasonable difference between science and philosophy.

Specifically, though, I don't see any connection between idealism and QM. The position of a photon is unknown until it is measured. Therefore, Idealism. What's missing in between to connect the two?

There's a big difference, from my view, between scientific realism, realism, physicalism, and idealism. All of these say different things. So when Bohr and Einstein argue over whether or not the probability in QM is due to the apparatus alone or because reality itself behaves in accord with probability that just does not say the same thing as the wave-function collapses because of consciousness is the fundamental nature of reality.

Something you start off with but I want to address:

Not being a physics graduate, I am restricted to reading popular books on the topic — Wayfarer

While I do believe QM is difficult, I do not believe that you have to be a physics graduate to speak intelligibly on QM. There is something more to the knowledge produced than the mere certification of an institution. All you need to do is be knowledgeable, which takes work. Histories are great. I actually own one of the books you recommended there :D (the one by Kumar). I don't think science can be understood apart from its history. But neither can it be understood strictly as stories of great scientific men. There is also a theory to understand as well.

And you don't need some degree to say you understand it. You just need to learn it, and you can do so with time and effort.

Not that you have to do so. But it makes sense for someone to know something before they have an opinion on its implications, doesn't it?

I certainly don't understand all of QM. I have no problem admitting that. But from the get-go it just seems a strange thing to say that the statement ,"Consciousness is the fundamental base of all existence" has anything to do with it, from what I do know about it. -

Limits of Philosophy: Desire1. How can philosophy get its hands dirty again with the lived reality of individual desire? — Kym

I'm interested in what you mean by "get its hands dirty again" -- you reference the stoics, so I think you might have something like establishing a school. But I find it hard to imagine that such a thing would be possible now.

2. How can philosophy influence the trajectory of a culture seemingly caught in death spiral down a vortex of desire?

I'm tempted to say nothing.

If we are beasts more motivated by desire than reason, and reason be the standard of philosophy, then we should expect philosophy to be ineffectual in influencing people.

It seems to me that there are two possible paths. One in which philosophers abandon philosophy in pursuit of other paths -- but then philosophy would obviously not have much influence. Or one in which philosophers rethink the bounds of philosophy to include desire in philosophical thinking.

For myself I really do like Epicurean analysis of desire and the practical life he advocates. But I sort of think that in our world now such thinking is pretty much limited to the individual -- as in, only if an individual decides to look for other answers and change themselves is philosophy going to even to begin to make headway. Philosophy is relatively weak in comparison with other means of influencing people. It's only really effective in self-reflection; which can include other people, but still requires that commitment to self-criticism and examination. -

Bernardo Kastrup?I don't see it. What's the argument?

Wiki doesn't give a very good overview, from my perspective. Not one that utilizes QM specifically -- we could just say that objects ultimately reside in our conscious experience of objects, and say the same thing as the wave-function collapses at the point in the causal chain within the mind.

The reference to QM adds nothing to that point.

What I see is sort of more of the same here as I see in Kastrup -- scientists too naive in philosophy doing bad philosophy.

Heisenberg, at one point after Copenhagen Interpretation had been "unveiled", told a room of philosophers that QM demonstrated how Kant was wrong because it showed we could know the thing-in-itself. Heisenberg was a brilliant mind. He even has some interesting philosophical speculations. But just because he was a founder doesn't mean everything he had to say on the topic was correct. This is one of those times.

I sort of get the same feeling here. When I look at the basic formalism and seminal experiments of QM I don't see how a reference to consciousness or idealism in interpreting that formalism makes sense of it. So maybe some physicists smarter than me believed such-and-such -- at the end of the day I just don't see how the argument follows. What lends this interpretation credence? Why should I believe it?

It seems to me that references to consciousness in interpreting QM just obfuscates rather than clarifies -- and from the examples I've seen in this thread and links it seems that the argument for idealism could be accomplished just as well without referencing QM. -

Bernardo Kastrup?Yeah, I think it's something that comes up mostly out of misunderstanding. I don't think QM has much to say on idealism, either way.

-

Bernardo Kastrup?Yes. In fact I'd say that it's not a resolvable debate at all. We can always save a belief from refutation. That would include beliefs about the fundamental nature of reality.

But a debate need not be resolvable in order for it to be fruitful. For it to be fruitful we would need to have some points on which we do agree.

With respect to QM, though, I'd say I fall more in line with SX in that it just does not say anything about consciousness somehow being involved. There are seven posultes of QM -- http://web.mit.edu/8.05/handouts/jaffe1.pdf

"Observable" has a lot to do with classical mechanics. As in, the wave-equation on which an operator acts is not an observable (edit: and the operator functions a lot like an apparatus -- it operates on the unobservable and, when solved, derives what is observed). It has nothing to do with consciousness. Or, insofar that it does, there are just more straightforward ways of putting the same point without referencing something which most people do not have a good familiarity with -- such as a tree falling in the woods.

I'd say that with respect to physicalism/idealism one such necessary point of agreement in order that we may fruitfully disagree is that we at least understand the facts of a discipline as that discipline understands them before we use it as a point in our argument.

So we might say that QM supports a notion of idealism, but not because consciousness is somehow involved in the outcomes of QM experiments. That's just a misunderstanding of what is being said. (and, truth be told, I'd say that if one can't do the math of QM, then it's fair to say that that person doesn't understand QM -- the formalism is a big part of the theory) -

Bernardo Kastrup?I am. The double-slit experiment does not imply that its outcomes are the result of consciousness.

If, for instance, a photon came across a double slit without it being built by anyone then the interference pattern would be the same. It's not that our setting up the double slit made the interference pattern -- any double slit would do, seen or not.

And if it's being seen is what's at issue here, then any old example would work just as well -- QM wouldn't need to be invoked. QM would be just as pertinent as any other example, such as a tree falling in a forest where no one is around. -

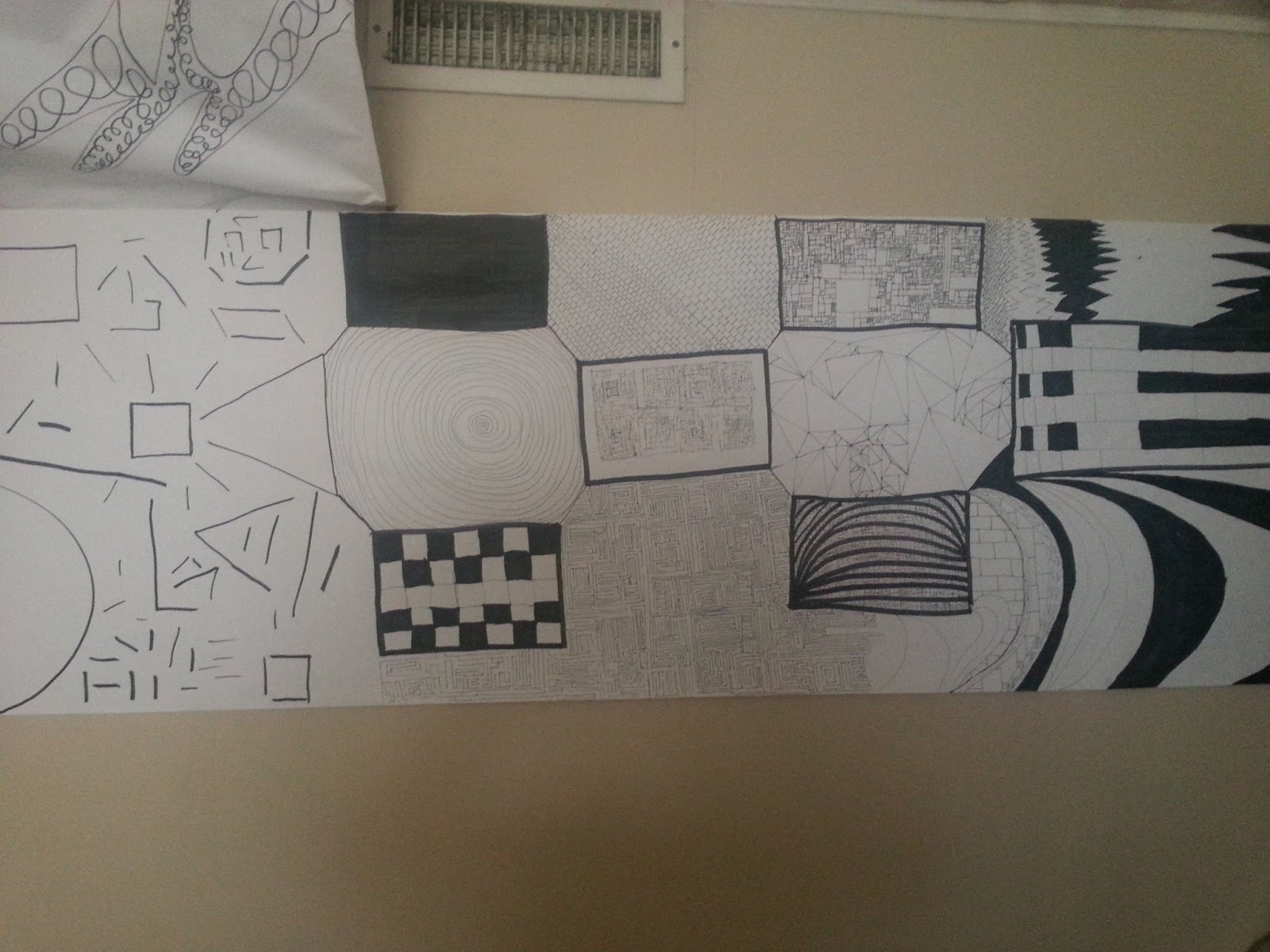

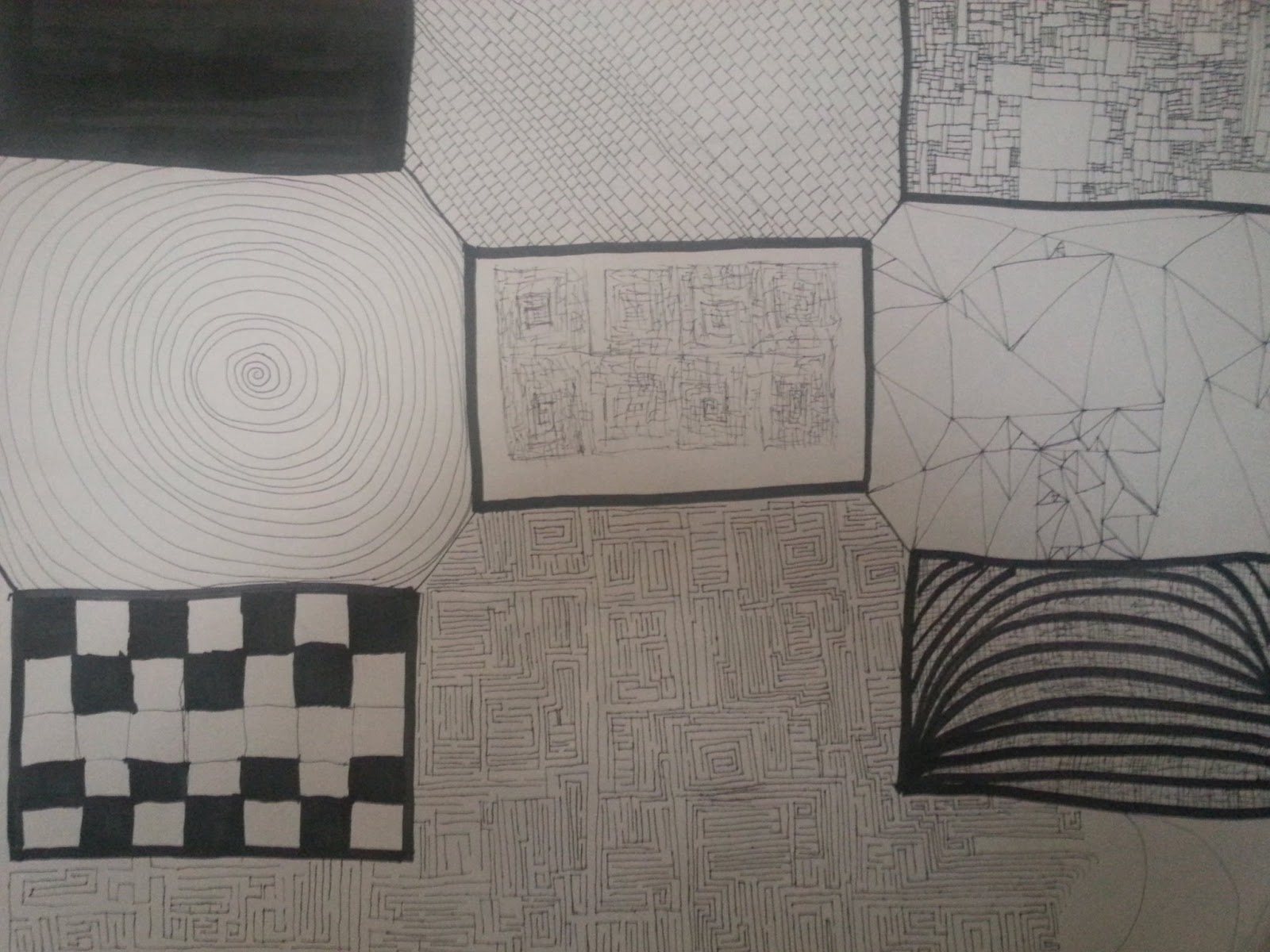

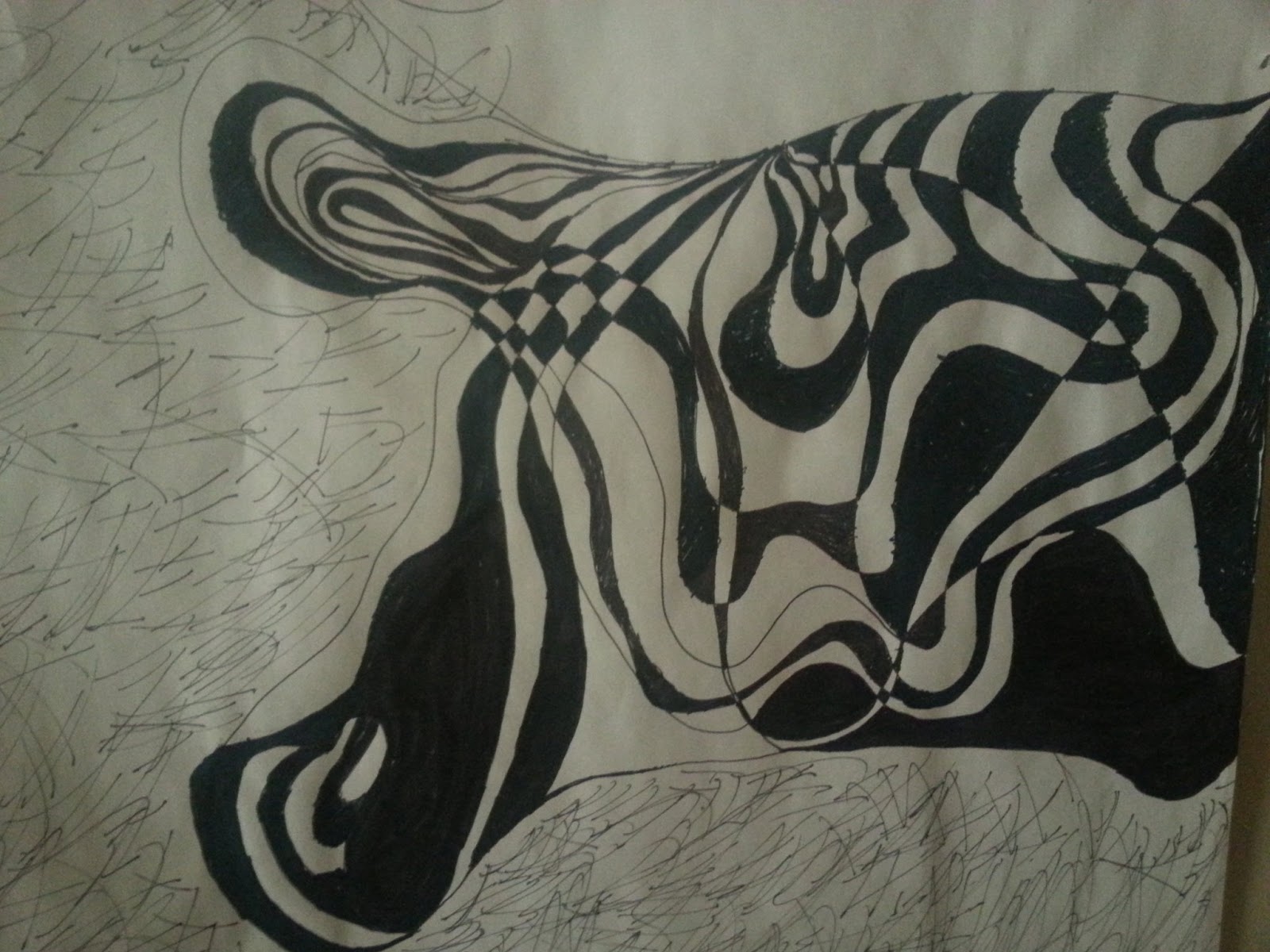

Get Creative!I do these abstract doodles with butcher paper and sharpies. I started doing them as a joke a long time ago, but then I actually started to like them. I follow a few simple rules: 1. Sharpies and blank paper only (only 2 tones), 2. nothing representative (just patterns), 3. no straight edges or any other tools to guide the line (strictly free form)

This one hangs on the wall in my apartment. The outside edges aren't as detailed as the middle -- I was going for a "stretched out" effect all across the paper. The 2nd photo just zooms in a bit on the middle to show some of the detail.

Also, I'm not super fond of the rest of this piece, but I did really like this one part:

It's just fun to play with patterns and see if you can come up with something semi-unique or interesting. -

Bernardo Kastrup?It's more a matter that a secular, non-religious outlook is normalised in a secular culture such as ours. As you say - this doesn't mean that holding this kind of view has necessarily entails 'scientism'. But many are more likely to accept that whatever answers there are to be sought, are best sought, or can only be sought, by scientific means. But even that has existential implications, in that the scientific stance is one in which there is an implicit separation between the object of knowledge and the knowing subject. Whereas in pre-modern cultures, there is a felt sense of 'relatedness' to the Cosmos; that sense of it being totally 'other' to the observer is not so pronounced as it has become in the modern age. — Wayfarer

I don't believe that the United States is a strictly secular culture. While religious life is in decline, it is still by the far the majority. I took a quick look over at gallup to make sure this was still the case and it seems to be.

I mean, you have an entire political block organized around religion with a fair amount of influence on how the state is run.

And the majority of people don't look strictly to science for what is knowable.

This monolithic secular view just does not exist in the United States. There are some secular people, and the state is meant to be secular. But the majority of people are still religious.

And, furthermore, while they are in a minority, there are still many scientists who are religious.

I'd say that there are other more likely culprits for a lack of relatedness to the Cosmos than a secular dogma.

And, to attempt getting back on topic, I don't think that a secular dogma is holding back idealism. Historically there have always been trends towards this or that metaphysical stance in philosophy -- including idealism!

From my perspective this all just seems way off the mark. I get that you have issues with a secular worldview. But I don't think that non-religious outlook is so normalized as you seem to believe, and I certainly don't believe that secular beliefs are the reason why Kastrup is being criticized here. -

Bernardo Kastrup?Not least because of its use by culture warriors such as Jerry Coyne and Richard Dawkins to attack religion at every possible opportunity. — Wayfarer

Whether they are attacking religion or not -- evolution is a well-founded scientific theory. And a very large percentage of people do not believe it to be true (at least with respect to human beings). So it's just not the case that most people listen to science as the source of all truth, the way, and the light. By the link I provided it appears that the Bible is more influential in that regard. -

Bernardo Kastrup?in that most folks don’t ever give ontology or cosmology much thought at all, if ever. — snowleopard

While I agree that formally speaking such thinking is unpopular, I'd say that informally it is not. People talk about their beliefs regarding the world and its beginning quite often, in the right setting. And I'm not so sure that people, at large, lap up scientific theses as a Biblical truth, either. Some people do -- it's something which some groups have fallen into the habit of doing without much critical reflection -- but I'd be pretty hesitant to say that there is a successful brainwashing program based on the sciences in practice, and much less so that it is successful even if there happens to be one.

This is 4 years old, but I don't think things have changed much: http://news.gallup.com/poll/170822/believe-creationist-view-human-origins.aspx

Evolution is one of the most well founded scientific hypotheses. But in the U.S it's regarded with suspicion by a very large percentage of the population.

I find it hard to reconcile the notion that science is a priesthood brainwashing the population with facts like that.

Scientism is off the mark. But that doesn't mean that the dominant pardigm is scientistic either. -

Body and soul...On "soul":

I sort of take inspiration here from Aristotle, but my best understanding of the term is the wholeness of a person -- so that includes my mental life, my emotional life, my physical life, my social life. And as much as I am philosophically inclined to avoid the word in the everyday use of the word I have encountered expressions that couldn't be expressed better without the use of "soul" -- "You and I have seen eachother's souls" is such a sentence that could not be translated into another sentence. It was the perfect expression.

It goes against my intuitions, but there does seem to be something to the word in the everyday sense that gives me pause. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?I'd probably fall closest to number 3. Seems about right to me.

-

Bernardo Kastrup?However, with respect, that doesn’t seem reason enough to stop reading at that point. — snowleopard

I could be more fair than what I was, I agree. But I'd have to want to :D. There's a lot of junk out there so sometimes I'll be less-than-fair to an author if I start to get the feeling that the argument isn't going to address what look to me obvious flaws in it and continues to move forward as if they just aren't there.

Anyway, my intention here is not to defend his ontology on his behalf, but rather to get input on his version of idealism, and idealism in general, so as to make some sense of it, one way or the other. The main reason being that my intuitive feeling, being more mystical than analytical, is that materialism, as the prevailing metaphysical model, fails to adequately explain even ordinary experience, never mind extraordinary or paranormal experience, and hence the ongoing search for an alternate model -- e.g. Idealism. Clearly it is predicated on the premise of the primacy of Consciousness, as the ontological primitive, and thus avoids the ‘hard problem’ faced by materialism, as there is no longer any need to explain its emergence, there being no ‘prior to’ Consciousness, and therefore no point of origin or causation. From there -- this being an admittedly simplified synopsis -- as the word idealism implies, it posits the emanations of the ideations of Consciousness (Platonic forms/ideas), akin to a Cosmic Mind, as the basis for the phenomenal experience of the individuated loci of Consciousness, i.e. sentient beings, which comprises one’s apparent subject/object perception. Our thoughts then become the recapitulation, or iterations, of that greater cognitive process. But of course one realizes that, while this avoids the so-called ‘hard problem’, it has its own hard problems, the challenge being to tie it in with the findings of quantum theory, evolutionary theory, the origins of life, etc. — snowleopard

Cool. Idealism is an interesting topic to me, at least historically speaking.

I don't believe the world is only consciousness in some ultimate sense. But then, I have deep reservations about positing any sort of ultimate ontology -- be it physicalism or idealism or neutral monism or dualism or whatever. Not that I haven't believed some of these to be true at some point. But I've become more skeptical with regards to fundamental or foundational ontology, in general.

Why would you say that the hard problems of idealism are reconciling it with science? I guess it depends on the idealism, but it would seem to me that you could fashion an argument from the findings of science to idealism. If the world were consciousness then it would explain how we could know about the world -- there is no disconnect between our minds and the world, in that case. True beliefs would just be micro-reflections of the world we inhabit. Correspondence could make more sense -- to correspond is just to equal a true statement. So when I believe a true statement it corresponds to a fact in the world; that the Earth revolves around the sun. I believe "The Earth revolves around the sun", "The Earth revolves around the sun" is true, and The Earth revolves around the sun = The Earth revolves around the sun.

Theoretically we could come to know everything because everything just is the set of true statements. (in this hastily constructed kind of idealism)

So you could actually say because we know the world through science we can infer that the universe is ideal as it explains how we can come to know the world -- the world is made of propositions so we should expect our knowledge to reflect that.

Nonetheless, it somehow seems important to conceive of an ontological/cosmological model upon which to base a cultural ethos. The question becomes, which one? — snowleopard

If that's the motivation for constructing some ultimate ontology, then wouldn't it depend on the ethos, first, and then hashing out which ontology to believe based upon how believing in it practically effects the actions of human beings? -

God and Critque of Pure ReasonOh, hey. That is a "who" there. Whoops! Sorry. I read "Would", for whatever reason.

-

God and Critque of Pure ReasonYes and no at the same time. I love Kant, but we all still argue over interpretation, and interpretation is a big part of Kant scholarship. So yes, it's interesting. But if you haven't read much else in terms of philosophy, then no. It's dense and difficult and could turn you off. If you have that "spark" then that's not going to stop you, but there are definitely other interesting philosophers who talk on the same topics who aren't as dense.

-

God and Critque of Pure ReasonIt is mentioned in the CPR. But if you're hoping for something in the affirmative, then you should look for another writer.

-

German philosophy in English?I think translations are roughly sufficient. Or semi-smoothly sufficient. I don't think you need to read the original to understand the arguments, especially on a first reading. It's only when you delve into the nitty-gritty of argument for particular interpretations that translation becomes an issue.

So at an intro level, or even just undergrad level, you're fine. At a doctorate level you'd want to learn the language, but you're talking some odd 4-8 (sometimes 12) years of commitment there.

Since you mentioned Kant I'll note that I think Werner Pluhar's translations are on point. It comes with a particular interpretation of Kant, of course (as would be necessary with any translation) -- but he's the translation I read for clarity and an excellent index. -

Bernardo Kastrup?For a rigorous, analytical summary of his philosophical ideas, see this freely available academic paper: http://www.mdpi.com/2409-9287/2/2/10

I took a gander at the paper he linked in his 'books' page.

I stopped reading at this point.

Let us start by neutrally and precisely stating four basic facts of reality, verifiable through observation, and therefore known to be valid irrespective of theory or metaphysics:

Fact 1: There are tight correlations between a person’s reported private experiences and the observed brain activity of the person.

We know this from the study of the neural correlates of consciousness (e.g., [5]).

Fact 2: We all seem to inhabit the same universe.

After all, what other people report about their perceptions of the universe is normally consistent with our own perceptions of it.

Fact 3: Reality normally unfolds according to patterns and regularities—that is, the laws of nature—independent of personal volition.

Fact 4: Macroscopic physical entities can be broken down into microscopic constituent parts, such as subatomic particles.

Seeing this I sort of gathered that the man is just not versed in philosophy very well. You can't just neutrally and precisely state four basic facts of reality without having at least some notional commitment to a metaphysics. "Fact" is even a controversial word. You can be precise, but why the claim to neutrality? And if something is verifiable by observation alone, then you haven't contended with philosophy of mind or science, by my lights. Surely you have to have a sort of idea, at a minimum, about perception (mind), or have a way of dealing with the underdetermination of evidence (science).

I don't think he means badly, at this point. But I also don't think he's really delved much into philosophy. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?It might help, too, to note that beliefs of the form "does not exist" or "does not necessarily exist" would also count as metaphysics, in my view. So we might talk in terms of forces but believe there is no such entity, but it is a convenient shorthand for describing the behavior of fields. Or we might take an instrumentalist approach to scientific discourse and claim that while it works it does not speak of what exists, even while making what appear to be existential claims.

Perhaps you could say you are a sort of agnostic and say that all entities named by science may or may not exist, but even this sort of ploy seems to me to take a sort of skeptical stand towards metaphysics -- which is either a convenient opinion which suits one's feelings, in the absence of an argument, or a sort of belief with regards to the knowability of entities in the presence of an argument, and would count as a kind of commitment with respect to metaphysics because it deals with entities and our minds relation to said entities in such a case.

Unless science, in spite of appearances to the contrary which seem to make claims about what exists and how it exists, could be construed to somehow be about something else in actuality -- sort of like an error theory of science -- science talks about what does or does not exist, therefore is discussing metaphysical topics. And any argument which says science does not deal with entities would itself be a metaphysical thesis, so I don't see much escape from the charge of "doing metaphysics" here.

Not that there's anything wrong with that, by my lights. I don't think there's anything useful to be had by trying to separate the two. Science is just a bunch of arguments, in part empirical and in part more a priori. It's a hodge-podge of impurity interested in asking and answering questions, not some sort of regimented methodology followed with ritual precision to obtain the pure stuff of nature. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?I agree there's a difference between those two, but I don't know why you'd think science is restricted to one or the other.

How would a biologist work under such a regime? "We agree that yeast exist, but we do not characterize them" isn't exactly what microbiology looks like. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?So, on that angle at least, only regularities are required, without which everything would be incomprehensible chaos anyway. — jorndoe

Regularities may be all that are required, but even specifying some belief in regularities is already a commitment. And if scientists said all things were made of pixie dust, rather than particles, then these would also be commitments. Since they are commitments about what exists, they are metaphysical commitments.

A commitment can be changed, of course, upon pain of further reasoning or new discoveries. We could just as well use "belief" for "commitment", I'd say. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?I guess my thinking is this -- if you can model a physical system without reference to the principle of least action, then in what way must we be committed to whatever metaphysical commitments which come with it? With a system as simple as a javelin being through we certainly can do so -- and just because we can derive equations from some principle that does not then entail that we must do so.

I guess the example is just meant to be illustrative, though, rather than definitive. And yeah, it does seem more general. I had myself a bit of a wikipedia reading session after your reply to check myself and see if I was mistaken, and I was indeed ignorant of it being present in physics at a higher level. So I could be speaking a bit too ignorantly here, after all.

It seems, though, that the point could be made more simply. We don't need the most general form of physical theory to demonstrate that metaphysical commitments are part of physics. Interpretation of force, gravity, inertia, mass, and so forth fall squarely within the realm of metaphysics, by my lights. -

Propedeutics QuestionsI doubt that it's central, but I know I'd just say that I find it fun and interesting -- and that's enough for me.

-

What is the solution to our present work situation?This sort of thinking is a kind of madness which arises when we decide to accept what is unacceptable, to my mind. Prison is a good thing which cures me of what I am inflicted by. My brother only hits me because he loves me so much. Work is actually necessary for freedom. The peasants need the nobles to structure their lives and give it meaning.

I can acknowledge you may be different. But I'll gladly forgo that need and suffer the horrible bondage that comes from not having to clock in -- were it consequence free, at least. -

Does doing physics entail metaphysical commitments?I believe there is no meaningful difference to be made between scientific and metaphysical beliefs.

That being said, I have to echo some of what StreetlightX says above. The blog post does come across as a bit odd. In particular...

This physical system has a kinetic energy, determined by the velocity and mass of the javelin, and a potential energy, fixed at any moment by the javelin’s height above the ground and its weight. The physical quantity known as the action of this system is defined by physicists in terms of changes in these two quantities of energy over specific periods of time. The Principle of Least Action requires precisely and only one thing: that the actual value for the action of this system during any such interval should be the smallest it could possibly take. In this particular case, this translates into the requirement that during any period of the javelin’s flight, out of all the possible paths between its initial and final location for that period, the javelin must follow the path that ensures the action of the system will be zero. As it turns out, only one path meets this requirement, and it is the one that Newton’s laws of motion describe. So, Newton’s laws follow from the Principle of Least Action.

is just a bad argument. There is no such thing as "the action of this system", and the Principle of Least Action is something the writer is importing here. There isn't anything to be said about paths in basic energetic modeling, only that energy is neither created nor destroyed. So Kinetic Energy is converted into Potential Energy as the javelin travels to its apex, and converted back into Kinetic Energy as it descends to the Earth where it is transferred to the Earth upon impact. Further, motion is different from energy in that it has a direction that is specified, and deals in forces rather than in energy.

If the principle of least action requies that the actual value for the action of the system during any interval should be the smallest, such reasoning doesn't enter in arguing where the javelin is going to fall or what is going to happen. The writer may see something of his principle in basic motion puzzles, but I sure don't. It just seems inserted in the middle of a text-book problem meant to explain the basics of motion without doing any argumentative work, and then is assumed to be required.

If that be the case then the rest -- possibility, actuality, paths -- are likewise not really part of the reasoning, since they all follow from this principle.

While it's the case that metaphysics is part and parcel to science -- or so I believe -- I'd say the writer here is way off, and hasn't really done the work necessary to understand the science. -

What is the solution to our present work situation?Hahaha. No insult intended. Sorry :D

tldr: It's reasonable to look at hunter-gatherer societies as affluent, rather than simply eking out a mediocre existence because as noted in this thread there are two sides to the problem of scarcity -- there's production, but there is also desire. There are still limitations, but the characterization of hunter-gatherer economies as purely limited to physical existence is too far a stretch largely rooted in our own theories of economy developed with our own particular social expectations. -

What is the solution to our present work situation?A bit off the beaten path, but a good read when considering older economic forms: https://libcom.org/files/Sahlins%20-%20Stone%20Age%20Economics.pdf

EDIT: I realize that's a whole book. But chapter 1 suffices. -

The CharadeSo I think my response depends a little bit on whether or not what you propose as solution is a strict rule, or more of a suggestion. As a suggestion I'd probably find little to no disagreement -- I have my own set of little rules I try to use to think through questions that crop up based upon my own tendencies or errors past. And, sure, often times we simply need to rephrase our question to make it more specific because we may just be following a bad habit that leads nowhere, after all.

As a rule, though, I think I'd disagree. I'd go to Heidegger to do so -- heck, one could argue that Being in Time just is a circle where Heidegger is clarifying what he already believes to be the case, chasing his own tale, but I'd still say it's good philosophy.

But before saying much more I'll just wait and see in what capacity you mean your solution. -

The Charade

M'kay, maybe there is more disagreement after all then.Indeed, I don't agree with the phrasing. The way I see it, it can be both the very question and what we're asking for. But acknowledging at least part of the problem is a start. — Sapientia

At risk of committing the error you're after I'm tempted to ask: What is the problem?

I wonder what sort of pretence, exactly, you think philosophy might invite. Like, that we are just pretending that we do not know something, maybe? Sort of like a parlor game rather than something we are asking?

The mistake, as I gather so far, has something to do with the habits of the philosophically inclined, and something to do with how they formulate questions, and in particular their usage of questions of the form "What is [x]?" -- that when the philosophically inclined ask such a question perhaps they are sort of deluding themselves into thinking they do not know what they, in some sense or other, know. Or that they are playing a game of making the obviously false appear true to them, at least for the moment, because they are in some kind of habit whereby they believe they're digging deeper into truths but are actually just chasing their own tail and rehashing what it is they already believe.

That's my closest guess.

And I think, if I'm reading you right, your solution is to rephrase questions of the form "What is [x]?" to be more specific, or to reflect on whether or not what you're asking after is actually something easy to answer without anything more deep or profound to it. -

The CharadeI can sort of relate to what I'm critical of here. I'm certainly not suggesting that I've never been guilty of it myself. It's just that, with hindsight, I look back at it differently. We experience these moments of realisation from time to time, and they don't always cast things in a good light - or at least they shouldn't, otherwise I'd think that there's something wrong with you: a chronic case of naivety, perhaps.

I once - "famously" :joke: - asked, "What is an apple?". Although, even then, there was part of me that thought, "Do we really not know?", and that's quite a forceful impression. It's a question I think we - those of us with a philosophical bent - could do with asking ourselves more often. — Sapientia

I think I'd just say that it's part of the practice of philosophy to route out our own ignorance -- so even when a question ends up being a bit silly, it's actually in line with what I'd still consider good philosophy. We're just identifying yet another time where we're making some sort of mistake. (since we'll never actually be free of intellectual mistakes)

And then there are the times when I'd say that when something may look silly on its surface it actually ends up interesting. "What is Google?" actually struck me that way -- on its surface its sort of silly, but understanding the ins and outs of an algorithm is actually kind of interesting.

Or, to use a classic question, "What is the meaning of being?" inspired some really great philosophy.

Not that I'd say every time you or I happen to ask seemingly simple questions we'd be able to then write good philosophy :D.

But I think I can dig the gist of what you're on about here -- or at least this is how I'd put it, while uncertain that you'd agree with this phrasing -- that sometimes the problem isn't what we're asking for, but rather the very question we are asking. -

The CharadeIs there something about philosophy which invites or attracts a sort of pretence? Is there something about it which opens up for debate that which we already know? Is everything really a matter of personal opinion? — Sapientia

I think philosophy can invite a sort of pretence -- but I don't know I'd say that said pretence is unique to philosophy. I think that simple questions like the one's you use as examples can be asked earnestly. I'd say there are times that what I thought I knew appears, for whatever reason at that time, to be something I don't know -- and so I ask something along the lines of...

What is faith? What is education? What is the purpose of education? What is scientism? What is a philosophical question? What is common sense? What is Google? — Sapientia

... which is not to say that said question is necessarily profound. Sometimes the reason I might ask such a question is something as simple and boring as self-deception or confusion.

but not always.

I'm not sure I follow why you're asking if everything is a matter of personal opinion, though. If it were, wouldn't the simple questions have whatever answer we wish, after all? It seems to me that in asking a question that seems a bit silly -- if we are asking earnestly -- we are hoping for something more than mere personal opinion, even if the answer doesn't quite reach the demands of knowledge. -

What is the solution to our present work situation?I'd say limiting work hours is more realistic. One, it's a demand that's worked to build a movement before. And two, there are large sections of the economy which are superfluous. We produce enough goods and services to meet people's needs. We just don't distribute those goods and services equitably.

-

Why do you believe morality is subjective?I think I have already addressed this, but I will try again. "Equality in treatment in all men" means that, for a given situation, the treatment you choose must apply to yourself, and to others, and from yourself, and from others. With this, the treatment "do as you please, and only as you please" cannot be just, because what pleases you does not necessarily please others. So there is a contradiction, both when you apply the treatment to others, and when others apply the treatment to you. — Samuel Lacrampe

I feel we're kind of going around the circle, too, but I'm willing to keep it up to see if something latches on.

My rejoinder here is that the same can be said for the golden rule you propose. "Do unto others as you would have done unto you" leads to a contradiction -- because what you want may not be what someone else wants, especially if the standard is necessity.

To contravene this sort of criticism of the golden rule others have developed the platinum rule: "Do unto others as they wish to have done unto them" -- but this likewise does not meet the standard of necessity, because you may not wish to do what I want you to do for me, and I likewise. It would not necessarily please any of us, though we may find ourselves pleased by others.

Even so, I would also say that justice isn't about pleasing others at all. Justice is about fairness. It's different from moral goodness, as I see it. They are actually very often in conflict with one another.

And I want to add a side note to the conversation: I realize that the topic is really about the objective/subjectivity of morality. But I think the meta- position on morality is better reached in the weeds, so to speak, rather than in yet even more abstract arguments regarding the objectivity/subjectivity of morality. My long term strategy here is to explore one of the main arguments for moral nihilism -- the argument of diversity in ethical commitments leading to a reasonable inference that there is nothing objective about them. I think a flip side of this argument is: even if you come up with something that sounds universally agreeable, that we only do so by abstracting moral norms to a point that they say virtually nothing about proper conduct.

While I know the response to this argument, from the moral realists perspective, is to point out that no subject matter has agreement, I wonder if there might just be degrees of agreement/disagreement which makes the inference to objectivity/subjectivity reasonable. -

What is the solution to our present work situation?At this point I'd settle for the 20 hour work week without reduction in pay. It's not the sort of goal I dream of, but it's good.

-

Your take on/from college.I was wondering what other members think about college, if it's worth it, the reasons why one should go to college, and some such matters? — Posty McPostface

I think it was worth it. It costs a lot of money, but that can be managed. I wouldn't know the things I know without having had that time to study -- I'm still an autodidact but I learned more with access to knowledgeable people and adequate time to put into studying and learning. I think more clearly and rationally -- and am able to communicate those thoughts -- better after having learned in college than I could before.

It so happens to look good on a resume, some of the time. But good connections and experience look even better than an education on a resume. What I got out of college was knowledge, and I think that a worthwhile pursuit unto itself.

Economically speaking? I'm not so sure. But that was a secondary reason for going, from my perspective. I hoped it would help out, but I primarily chose to study things which I found difficult to study on my own, and felt rewarded for it after putting the work in; not because I have a piece of paper that says so, but just because I learned while there.

I think the price tag is too large. From an economic perspective I sort of wonder if it was worth it. But that's more politics, from my perspective, than whether or not I should have gone. I come from a family that values education unto itself, and it's one of the values taught that happened to stick with me. -

Why do you believe morality is subjective?As mentioned above, the golden rule is directly linked to justice; so much so that one cannot be followed without the other. Your behaviour of "treating everyone as some sort of means to whatever happens to please me" clearly breaks the golden rule because you would not want this behaviour from others onto you. And if the golden rule is broken, then the behaviour is unjust. — Samuel Lacrampe

Leaving aside what I want for now, and whether the golden rule follows from justice...

I would say that on the formal level, if not in spirit, my maxim follows your definition of justice. But that's what I was trying to get at in the first place; what you state justice is -- the equality of treatment of men -- is not robust enough. The formal statement is too permissive, because it clearly allows for things which are not just, at least as yours and my intuitions would have them (since I don't think that the maxim I produced is exactly just, either, merely something which follows from your formally stated definition of justice). There must be more to justice, in that case, than merely the equality of treatment between persons. -

Why do you believe morality is subjective?To generalize: "Equality in treatment in all men" means that for a given situation, a just treatment is determined such that all men must follow it for others and themselves, as well as from others. This is really nothing more than the golden rule. — Samuel Lacrampe

They are connected, because both are derived from justice. Golden Rule: "Do unto others as you would have done unto you" is the only way to preserve equality in treatment when interacting with others. Just War Theory: how to conduct a war while preserving justice. If you are in conflict with a neighbouring country, how would you want to them to behave towards you in order to resolve the conflict? E.g., you would likely want them to first use peaceful acts before resorting to force. As such, to preserve justice, you ought to behave the same way towards them. Thus the Just War Theory is related to the Golden Rule — Samuel Lacrampe

If they are both derived from the golden rule then then golden rule would differ from justice. In which case I'd be back to your original definition --

Justice is defined as: equality in treatment among all men. — Samuel Lacrampe

In which case I'd say that my principle is derived from your notion of justice. Or, at least, is compatible with what is stated by your definition of justice. So if I treat everyone as some sort of means to whatever happens to please me, then everyone is treated by the same rule, and would at least count as equal treatment.

Your counter-example to this was a person who wanted to kill a person who wanted to live. But this doesn't show that my principle isn't derived from your definition of justice. It's in line with it just as much as the golden rule is. Unless any conflict in desire counts as a counter-example?

In which case the golden rule also wouldn't count. What if I don't want to be treated like you want to be treated, after all? Or, in the so called platinum form of said rule, what if treating me as I want to be treated goes against what you want?

I'd like a massage, after all. Why aren't you giving it to me?

No, I don't think a mere conflict in desired outcomes would be enough to invalidate a principle, given the principles you've lain out here. After all, even if it is a just war, we both want to win it once it starts.

Which is just my way of saying that you need a more robust theory of justice than the preservation of the equality of treatment. It is too permissive to count for justice.

Moliere

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum