Comments

-

What are your normative ethical views?But my understanding is, very briefly put, that the purpose of life is to awaken, and to serve awakening. To what? one might ask. I think you have to be able to develop a sense of gratitude, and also a sense of wonder at what most people think is ordinary (although that is by no means all there is to it.) — Wayfarer

If I can jump in, I agree with this purpose. I share these values. But I view it as a chosen purpose. We can identity with this notion of virtue, having experimented with others perhaps.So the sense, common to a lot of existentialism, of having been 'thrown into existence', isn't warranted (although I hasten to add, I could easily understand why many people do feel that way, like the poor unfortunate refugee diaspora.) — Wayfarer

While I'm sure that there are tortured existentialist that fit this bill, I don't think contemplating or pointing out our "thrown-ness" has to be "poor-me" or "a stranger and afraid / in a world I never made." Sure, the scientific image provides a plausible story, but that this in particular happens to be the plausible story is part of our thrown-ness. Upon reflection, the world appears radically contingent. It could have been another way. Other worlds are not all logically contradictory.

...because of that we actually have a reason for existence, and it's up to us to work out what that is; I think a good deal of unhappiness is caused by the unwillingness to face up to that fact (for which, see Eric Fromm, Fear of Freedom). — Wayfarer

This is very close to Sartre's existentialism. We are "condemned to be free." So we are tempted to fall into a state of "bad faith" and describe ourselves as objects with a fixed nature. My problem with Sartre was the unstable blend of world-fixer and poet of radical freedom.

And also we have stewardship of 'spaceship earth', which, in my view, is the only vessel we're ever going to have (so we have to overcome our promethean sci-fi fantasies of interstellar travel). — Wayfarer

I'm surprised you think we're stuck here. We might destroy ourselves before technology liberates us from this spaceship, of course, but we'll be pioneers again if we don't. -

Meno's Paradox

I don't think our views are that far apart. I'm just arguing that induction is psychologically rather than logically grounded. It's mostly just a "gee whiz" point, since I can't help but trust induction like everyone else, despite this gap that I see between logic and expectation (which can be understood alternatively as a hard-wired premise of uniformity in nature.)

That said, I continue the exploration. How would the chicken determine that a man was nothing to put its trust in, if not empirically? "Humans have violated expectation before, so we should (or just do) expect them to violate expectation again. We humans have learned not to trust induction without reservations, but we seemed to have learned this inductively. "Inductions have failed in the past, so they might fail in the future." Induction is to us as the human is to chickens, perhaps.

I agree that we strive to put anomalies or variances under a law. I agree that anomalies can only appear via a contrast effect in a largely invariant or law-governed context. I remember a Ted talk where the speaker stressed that consciousness is especially directed at violations of unconscious expectation. So the expected becomes an invisible background. The mind deals with the troubling or opportune "figure" against this ground. He painted a vivid picture of the mind as a humming expectation machine. -

Meno's Paradox

I think I'm more saying that nature as far as we can tell is and has always been uniform, even if only statistically, and not deterministically so, and that, secondly, a nature that were not uniform would be utterly unintelligible to us, and that, lastly, it makes no sense to speak of any purported lack of uniformity 'manifested' by a 'nature' unknown to us. — John

I agree that nature has been reliably uniform and that a lawless nature would be unintelligible. But it does make sense to speak of a violation of expectation.

Perhaps the most famous illustration of the problem of induction was given not by Hume, but by Bertrand Russell. Russell imagines a chicken on a farm. The farmer feeds it every day, so the chicken assumes that this will continue indefinitely. One day, though, the chicken has its neck wrung and is killed.[6] — Wiki -

Meno's Paradox

I wouldn't say that we have no rational warrant but only no deductive warrant. Because we can't live without induction, it's counterproductive to deny its strange rationality. But I do think your support it appeals to the same uniformity that you are trying to prove. It's something like: the future will be infer-able from past in the future because the future has been infer-able from the past in the past. the future resembled the past in the past. Don't get me wrong. Your argument appeals to me. But it seems like your assuming the uniformity of nature to establish the uniformity of nature.I actually don't agree that we have no rational warrant for expecting the invariances we are so familiar with to continue to be. There is a huge (relative to each individual at least) body of evidence that seems to show there are no reliably recorded incidences of contraventions of the so-called laws of nature (it was probably a bit hard to record any such miraculous events that might have occurred prior to visual recording technologies, though). I would dare say none of us can claim to have personally witnessed such an event. — John

https://www.princeton.edu/~grosen/puc/phi203/induction.html

I agree that lawful = intelligible. But do we expect the law of gravity to switch from an inverse square to an inverse cube law? Or the speed of light in a vacuum to halve? (Seems logically possible and intelligible.)Since we can only go on what we have experienced, and since nature cannot even be intelligible to us at all unless it is conceived as lawful, and since even if we did witness an apparent contravention we could have no way of knowing that it was not just a manifestation of some law that we are not yet familiar with; I would say we have pretty good warrant for expecting things to continue as we have known them to be thus far. In fact I would say that the nature of thought is inseparable from the nature of the world. — John

Just to be clear, I do expect and expect everything else to expect things to continue along as we have known them so far (with the predictable "deviations"). But I think our warrant is just hard-wired prejudice or gut-level assumption of the uniformity of nature. Support for "nature is uniform" is naturally going to be empirical, but why should observation have weight unless the uniformity of the past and the present with the future is assumed? -

The purpose of life

I don't know. Thinking that the point is to be happy doesn't mean expecting or demanding to always be happy. It's just the attitude that suffering is toll one pays. Also, why seek for a sense of security? I'd call this an aspect of happiness, feeling safe. So even the desire to believe that life is about the pursuit of happiness looks itself like the pursuit of happiness. I'd even conjecture that we tend to tolerate painful "truths" only as tools for the restoration of peace. Homoestasis, return to the creative play. That seems to be the game.So I think people like to believe that happiness is the purpose of life. But I think this is a pipe dream that nevertheless hoodwinks people into a false sense of security. — darth -

Meno's Paradox

I do like this theme.( I enjoyed Steiner's Heidegger.) Being is the "light" that discloses beings. And Being-as-concept is itself disclose by...Being-under-erasure? It's both profound and empty. I'm also interested in that which exceeds the concept, even as the concept structures it and makes it speak-able. It's 'sensation-emotion' or the overflow (underflow?) or the sensual that Feuerbach opposed to Hegel's concept-blob.Likewise, being cannot itself be, but is rather the be-ing of beings, so to speak (sound enough like Heidegger?) — John

I agree. The distinction between the self and world or subject and object exists within a unified concept system, except that concept becomes the wrong word, since things and concepts are one and the same in a peculiar sense. This concept system is "immersed" in the nonconceptual like a spiderweb in the fog or like leaves on a branch in the wind. We know there is redness other than the idea of red and pain other than the idea of pain, but we can't deliver it via marks and noises. Sort of like Being-as-concept and Being-under-erasure.I think that to be must be to be for us; because even to be in itself is to be in itself for us. This was Hegel's main point against Kant, at least as I read him. There is, thus, no coherent distinction between the in itself and the for us, except for us. I think, therefore, that in a sense probably beyond what Hegel Himself intended, the "rational is the real".

So, for me the whole question about the intelligibility of nature is a kind of furphy. There really is no nature apart from thought! But that is not an idealist avowal, because there really is no nature apart form material, either. I think of the Buddhist notion of 'interdependent arising' in this connection. So, if there is no nature apart from thought, then nature itself just is intelligibility itself. After all what else other than nature, of one kind or another, be it physical, human, mathematical or linguistic, could be intelligible? — John

Nature as concept ("what-happens") seems like a system of projected necessities. So, yeah, it is intelligibility itself. Even the "supernatural" would have to be fit into this system of nature to be intelligible, it seems to me. A "miracle" would just modify our notion of the possible or the to-be-expected. There's nothing outside the concept-system, for "thing-hood" is intelligible unity, always in relationship except for the paradoxical or infinite notion of the "whole." The totality is the only "miracle" one might say, but it's not a miracle that violates a projected necessity. It's just (apparently) radically contingent, because there's no-thing outside it to put it into necessary relationship with.

But don't we ferociously expect the future to resemble the past? It's so gut-level and yet not deductively valid. He published an extremely short version of the treatise as a marketing ploy, and this was at the center of it. I think his true target was "metaphysical" necessity. Maybe deductive necessity is the kind of necessity we project without deductively established warrant. This too is both empty and profound, because we are going to go on expecting not to fall through the floor when we step out of bed.For me Hume's problem of induction just sharply highlights the fact that induction is not pure deduction from axiomatic first principles, but speculation based on observed invariances. I think this must have been obvious long before Hume, but he was the first to shine a spotlight on something that was probably previously simply taken for granted. — John -

An Image of Thought Called Philosophy

That's how I understand as well. (Of course the issue of what he "really" meant seems secondary to the exciting and independent theme of thought-idols constraining thought.If I understand this correctly, it's that Deleuze is concerned with the "canonization" of philosophers, and the subsequent assimilation of thought. Thus thought is constrained by the thought-idols of the past. — darthbarracuda

I relate completely. Harold Bloom's theory of the "anxiety of influence" is basically exactly this. We don't want to be imitations or acolytes or fanboys. To distinguish one's self and to have one's own philosophy is to be, in Bloom's terminology, a "strong poet." For me philosophy is deeply parricidal. It becomes conscious of and incorporates the very anxiety of influence that largely drives it. But, anyway, yeah, none of the old masters are sacred. They're dead and their world is dead --or at least radically transformed. And yet I, too, have been hugely influenced by some of them. Schop and Nietzsche were big figures for me. I can almost sum up what it is that I've think I've learned in "reading NIetzsche against Nietzsche" in order to sort the wheat from the chaff. Hegel via Kojeve was also a book that set me on fire. Then, of course, there's W. James, a man of style and heart.If this is true, I have to agree. In fact this kind of reasoning has been running through my mind a lot recently; although I get a lot of influence and inspiration from the philosophers of the past, I also feel the need to distinguish myself and have my own philosophy. I don't want to just be a philosopher-fanboy, an acolyte of one single person's ideas. Aristotle didn't have the Truth, nor did Aquinas, nor Descartes, Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, etc. — darthbarracuda

Thus I try to take a more hermeneutic approach, synthesizing the thought of many thinkers before into my own thought. I think the best method of doing this is by identifying the questions/problems that each thinker struggled with: for even if their answers are insufficient or incorrect, they at least identified an issue that must be dealt with. The answers change, the questions remain (unless you're Wittgenstein). If you limit yourself to the answers (the "story") — darthbarracuda

The focus on problems reminds me of Popper. If memory serves, he insisted philosophers be read in the context of the intellectual difficulties of their time. For me the questions that remain are first and foremost existential. Who should I be? That for me shapes almost everything else, because even the questions we concern ourselves with seem strongly related to the value we assign to that sort of questioning.Thus I try to take a more hermeneutic approach, synthesizing the thought of many thinkers before into my own thought. I think the best method of doing this is by identifying the questions/problems that each thinker struggled with: for even if their answers are insufficient or incorrect, they at least identified an issue that must be dealt with. The answers change, the questions remain (unless you're Wittgenstein). If you limit yourself to the answers (the "story") without identifying the question structure, you essentially end up with an extremely narrow and blind view of reality, believing in an interpretation without understanding what the interpretation is of.

I guess you could call me a scavenger of some sorts. Systems inevitably get updated or replaced - philosophical systems are no different from the OS on your laptop. I like to take a look back at the previous versions, see how the current versions build upon them, and mod the hell out of my rig for my own preferences while adding my own personal touch. — darthbarracuda

I can especially relate to the synthesizing theme. As I see it, we are never done rewriting our part, tweaking the system of maxims and insights and identifications that gets us through and (at best) allows us to be glad we were thrown into this world.

For me the sense of self-possession and "radical freedom" is central. Philosophy for me is something like a flaming sword against bluffs, cons, brow-beatings. It is ideological violence. We meet one another as friends, trading tools, (peer-to-peer) or we try to establish mastery without granting it to the other. There's the pop-psych book called Games People Play. I think the "transactional analysis" background of the book is pretty slick. We play the adult, the parent, or the child. All goes well in a transaction if the roles are compatible. This reminds me of Hegel's theme of recognition seeking. -

An Image of Thought Called Philosophy

Can we add desire and fear to the mix, too? A thinking being with fears and desires to drive his thinking. I think everyone is a at least a part-time philosopher. Is there a god? What happens when we die? What should I do? How can I know for sure? Can people who disagree both be right? Is life worth living? Is this or that sexual practice wrong? Is revenge wrong? Do words have exact meanings?All you need, in order to be a philosopher, is to be, in Descartes's words, ''a thinking being''.

I'd personally narrow philosophy down to bigger and grander issues, just so the word has some punch to separate it from thinking in general. -

Honest question: To any nihilists out there, what brought you to your realization?

I remember not too many months ago, I went through a sort of anxiety/depression at the face of death. I would think about how there is really nothing but the present moment and that literally each passing second right now is irreplaceable and that writing these words has taken 5/some odd minutes away from my life that i will never be able to get back. I remember feeling like my daily actions had to have depth and meaning, i.e, going on walks on the traintracks by my house was something I considered poetic and meaningful in a way, and If i didn't do anything ''poetic'' or aesthetically rewarding or immersive then i felt lazy and unmotivated because my day didn't have enough signifigance to me.

[/quote]

I can relate. What's fascinating is the dominance of the "time is money" metaphor here, thought this "money" (time) is used (hopefully) to purchase the profound and/or beautiful.

I like states of "creative play" where time disappears. I get absorbed in my math or even in writing posts like this and I forget about time as a shrinking wallet even as I write about "time as a shrinking wallet." We get away from the narrow, anxious self in play (or that's play's definition, maybe).

As to the meaning of life, I think self-sculpture plays a role. We know that we must die, that the sandcastle self we seek to enrich must go out with the tide. But that knowledge comes and goes, and it's not real when we aren't thinking of it. Our mortality is only a part-time job. More often we think of who we want to be tomorrow, which is a guy (or gal) at least a little bit better and wiser than he or she was the day before.

You might call me a "nihilist," though I think it's not a term worth using. I don't think there is some universal, grand "meaning" that dominates or gives law or justification to all things. I think it's better to think in terms of desire and fear, pleasure and pain. We know what these things are. The meaning of "meaning" is already obscure. I will say that "everything is empty" (or "all is vanity") hints at a profound perspective that does not, however, exclude care for all the little things. In fact, abandoning the question for the infinitely "big" thing can allow one to enjoy all of the little things, since one accepts that that's all their is and that these little things can but by no means must add up to a beautiful life that one is grateful for, however mysterious its coming and going. -

The purpose of life

I think you nailed. It's a "simple" idea, but so much falls out from this simple commitment. I say "commitment" because some find their happiness in the idea that their lives are about something more profound than happiness. But, yeah, I say that we pursue pleasure and avoid pain, with both understood to include sophisticated, "spiritualized" pleasure and pain.In a nutshell: What, if any, is the purpose/goal a human would strive towards, in living his/her life?

My own answer to the above question would simply be happiness.

Happiness here covers a broad variety of emotions and mental states including all sorts of satisfactory, comfortable feelings from peacefulness to orgasms.

This just underlines how happiness lies at the root of our actions. What do you think? — hunter -

I hate hackers

I wouldn't go that far. It's just that criminality is always with us as a species, so we take it seriously and minimize our risk. It does suck that we have to build so many fences and walls, literally and metaphorically, but "so it goes."And it's become normalised, we've lost sight of the fact that theft and destruction of property are actually unethical behaviours. — Wayfarer -

Meno's Paradox

I see what you mean, but don't you find it hard to think both of beginning-less time and also the beginning of time? So that would at least damage this eternal being's use as an explanation. I wouldn't say that such a thing couldn't "be" somehow, but I often reflect on what a god or a guru or any given X can be for us. I'm tempted to say that nothing can be greater than the thinking mind, at least for the thinking mind, precisely because the thinking mind can only "chew" what will fit "inside" it. So gods would have to be experienced in terms of sensations and emotions, for instance, and we only understand the guru to the degree that we already are the guru. Anyway, the "time glitch" I started with is one more reason I like the "engineer" metaphor. Hume's problem of induction also suggests a sort of glitch (some gap between inductive and deductive faculties that suggests that the projection of necessity is a sort of "mental primitive").I guess the only answer could be something 'eternal being'. Its 'always-having-being' puts it beyond both necessity and contingency. Spinoza's definitions of contingent and necessary being are, respectively: 'an existence dependent on something' and 'an existence not dependent on anything'. — John

"...for the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life."Dogma is the fossilization of thought and emotion; the antithesis of the spiritual. -

An Image of Thought Called Philosophy

Please, be poetic all you like. Half the fun here is in the writing of an especially self-aware "poetry."

If the person in question takes historical traditions in philosophy very seriously,then yeah,he would be reluctant to stray beyond the well-worn paths etched through the lands of thought by the ancients who travelled before him(sorry,felt like being poetic there).

However,on the flip side,if the person in question is adventurous in spirit and contemptuous of tradition,then this "power of history" that Deleuze refers to would have no effect on him and he would go on to discover original ways of thought. — hunterk

I have a great friendship with a guy who just doesn't get into "philosophy proper," and yet our idea of a good time is to drink 3 or 4 cups of coffee and walk around the neighborhood talking all night. It's "deep" conversation every time. That's how we roll. I paraphrase some of what I like in certain books in our 2-person dialect, and it's a great way to test for relevance. If one can't paraphrase for the non-initiated, then it's probably a technical issue, an optional issue, no more "sacred" than calculus. I respect technical issues. Math pays my bills. But there's a certain kind of philosophy that might as well be the fixing of air conditioners. And that's maybe the personality crisis of philosophy. Should we picture the philosopher in a lab coat? Or is he the wise man on the mountain? Or on the corner? -

Meno's Paradox

Thanks for the great response, John.

I generally agree. Some of most powerful myths seem turned "inward" toward the emotional aspect of reality. On the other hand, science dominates the measurable. I like that you mention the "conceived forces." We need them. My theory is that the explanations you mentioned are deductions from postulated necessity. It's a fine way to use "explain." There doesn't even seem to be another. But perhaps you'll agree that all the necessity we postulate (and fail to falsify or learn to respect as actual necessity) must be itself contingent. So there is a "just because" that seems to haunt everything. "Thrown-ness." "It's not how the world is but that it is that is the mystical."I think the difference between myth and science is one of degree and orientation, not so much one of kind. So, science seems to be oriented towards the perceptible world, to find its clues leading to causal explanations, that are themselves couched in physically conceived terms, but involve conceived forces which are not themselves directly observable. — John

Well put. I think James nails it here:...we would have no reason to reprogram ourselves, in any case, if we felt nothing. It seems you are saying that we generally believe what it suits us to believe and that we marshall our reasoning around those preferences, rather than it being the case that reasoning, determines or preferences in an unbiased way. If so, I would certainly agree. — John

I like to think of a table with uneven legs. We put more weight on some beliefs than on others. Then we are also shaped by different histories. If a certain harmony of beliefs and lifestyle obtains, the system stabilizes. A big (and yet simple) insight for me was that there was simply no reason to expect a single stable point at infinity to which all earnest inquirers must eventually their way. Why not many, varying (sufficiently) correct belief-systems?The individual has a stock of old opinions already, but he meets a new experience that puts them to a strain. Somebody contradicts them; or in a reflective moment he discovers that they contradict each other; or he hears of facts with which they are incompatible; or desires arise in him which they cease to satisfy. The result is an inward trouble to which his mind till then had been a stranger, and from which he seeks to escape by modifying his previous mass of opinions. He saves as much of it as he can, for in this matter of belief we are all extreme conservatives. So he tries to change first this opinion, and then that (for they resist change very variously), until at last some new idea comes up which he can graft upon the ancient stock with a minimum of disturbance of the latter, some idea that mediates between the stock and the new experience and runs them into one another most felicitously and expediently. — James

I agree. Probably it helps to envision unbiasedness as something sacred or heroic in order to move in that direction. Indeed, I suspect most of thinking types adopted such a goal. It's almost the "will to Truth" itself. And while I eventually became suspicious of the "will to Truth," I only did so in what felt like the pursuit of the unbiased truth about truth. You mention Hegel below. I was especially moved by Kojeve's (mis-)reading of Hegel. The "wise man" is stable in his satisfaction and therefore unbiased. He's a clean, flat mirror; the surface of still water. I also like Bukowski's "Don't Try."But, I also tend to think that apart from the polemic of believing/ not believing there is also the possibility of being openly unbiased. I also think that if this disposition is achieved, then the deliverance of intuition will be all the more reliable, and may actually be self-evidently convincing. For example, mystical experience ( if coupled with a truly impartial 'scienitifc' attitude) can lead to 'knowledge' which is beyond doubt for the knower. — John

I completely agree about knowledge that is beyond doubt for the knower. As a matter of prudence and style we may regulate who we discuss it with. (Hell, I chose to study math because I anticipated that the formal study of philosophy would be slavishly depersonalized and compulsively safe as milk. I only say what I really think to true friends and of course anonymously.

I never suspected we were this much on the "same page." Certain perspectives or investments are just foreclosed to those with other incompatible perspectives or investments. You basically nailed my objection to what I call scientism. It's just another righteous, self-hobbling heroic pose. I'm not against heroic poses/masks (they are almost "spirituality" itself, in my view, though the mask and the face become one) but only against (to me) ugly or weak poses/masks. Science deserves respect, but it makes for a sorry god. On the flip-side, I don't believe in ghosts, etc. I personally find a happy medium by viewing the spiritual in terms of concepts and emotions. "Since feeling is first," that's plenty. If the right things are "figuratively" true (for me), then that's more than enough -- though we do want a few people to "get" our poetry. The "dragon" wants to chat with other "dragons." If a person knows that they know, then it's not about argument but instead about discussion, the trading of passwords and slight tweaks. I insist on myth so much to batter at the fetishism of "mere rational thought," itself adored irrationally.This is not say it can be rendered into a discursive form which will, merely by dint of its logic, be convincing to those whose preconceptions are not compatible with it, though. It is kind of like the idea of 'direct knowing' in Zen. What is known in this way is simply beyond doubt and not something which could ever become the subject of a sensible argument. I think it is a uniquely modern tendency that is present in many people today to deny themselves any truck with knowledge of 'that sort'. On the other hand, I would say that if there is a truly rich kind of knowledge, then that is it. And it can certainly inform literature and poetry and the other arts, even if it cannot be justified by mere rational thought. — John

I love Hegel, largely through secondary sources. Kojeve's "Introduction" blew my mind. (Others were also good, but I'm sentimental about Kojeve's book).I can't comment on Spengler, though, since I haven't read him. I like some of Derrida's inventiveness, but I am not so thrilled by his impenetrability. I'm not convinced he would be worth the effort for anything more than a cursory reading of him. Hegel, or Heidegger, on the other hand.... — John -

Ray Monk on Wittgenstein's Philosophy of Mathematics

I relate to everything you've said, even about sets. I've been doing math all day, actually. And it's sets, functions, and logic. I don't intuitively think of the integers as sets (except when I'm trying to), but I do find it natural to speak of sets of numbers and sets of sets of numbers and so on. (I'm actually doing an independent study in axiomatic set theory this semester, too.) More on topic, I do think "worldly math" has an empirical foundation. Calculus earned our trust before it was made rigorous. We would continue to use it even if some contradiction were found in ZFC, for instance. So the quest for foundations seems aesthetically driven, which I can respect. I cooked up a construction of the real numbers this summer that I haven't seen elsewhere. It absolutely felt like I was sculpting. -

Meno's Paradox

Perhaps I abuse the word "myth" and use it eccentrically. One of Popper's essays described science as a second order tradition on the first order tradition of myth that included the civilized criticism of myth. The myths were no longer sacred. The second order tradition was itself a sort of sacred meta-myth. But I'm not so sure we can escape myth-making. Why would we eschew myth? If not in the name of the myth of the inferiority of myth? I suppose 'myth' is synonymous with 'hypothesis' here. From this perspective, myth and thought are tangled concepts, but perhaps should stop using "myth" this way.I cannot bring myself to think of thought in terms either for or against any myth such as "the natural goodness of thought in the traditional image", because to do so would be just another example of myth-making. And we should recognized that thought is prior to myth. — John

I agree with just about all of this. I am suspicious of "immediate experience" being taken too far, though. I think concept and sensation and emotion are terribly tangled in experience, though I just used words to seemingly break it into a trinity. I'm no fan of insincere doubt. We always already "really and truly" believe quite a lot, I'd say, despite our dutiful protestations in the name of what strange investment? (There are candidate answers, of course, but I'll stop there.)So, if immediate experience consists in being presented with a series of unrelated patterns, or even disconnected entities, then the real work of thought consists in penetrating to the order and relations that are implicit in the perceived regularities, and the unities they evoke in thought whether poetic or scientific; and to the recognition of the regularities which is enabled by memory, and which is conceived in terms of invariance. Of course, there must be an element of pure trust at work for thought to operate this way, and trust is anything but fashionable these days.

So, the implications of regularity and the justification for any postulation of invariance are not given in immediate experience, as Hume was keen to emphasize. But, firstly, nothing at all is given in mere perception as already noted, and secondly, if the idea is not to be trusted that thinking in terms of regularity, invariance, unity and causation, in accordance with principles that seem self-evident to us, then all of our discourses, apart form those which irrationally acknowledge and trust the God of science, are rendered on the same flat plane of the unwarranted. — John

I can relate to all of this. I'm willing to assert the importance of what might be called intuitive. I'm always invoking "images of the hero," because I see reason as the tool of the unreasonable human heart. I don't think the heart flails around blindly, though. Instead it "thinks" or rather desires in images. (Really there is a reason-heart unity, or we couldn't "reprogram" ourselves.) Rigor has some pragmatimatic justified. We skin our knees if we miscalculate. But posing as rigor or reason incarnate can also serve, for instance, the irrational heart's investment in a particular vision of the intellectual hero. Rigor is sexy or intimidating, etc. It's hard to ignore that philosophy tends to attract males especially. It's even hard to ignore the male preoccupation with status and hierarchy, from which I wouldn't dream of denying in myself. So I think all of this is lurking behind the "reasonable" reasons folks give for investment in either tradition or in a fashionable thinker. Who would you rather quote, for instance? Spengler or Derrida? And yet Spengler is probably more useful (as he was to the Beats) to those not playing the "have you read?" game or toiling in academia.This is the aporia at the heart of modern scientism and the fashionable kind of philosophy based on it which are both biased towards the empirical, and away from any trust in the intuitive and the purely rational. The continental philosophers as much as the analytic philosophers are responsible for bringing modern philosophy to this impasse. That said, both of these traditions have their own valuable practical (as opposed to genuinely theoretical) contributions to philosophy; the first to the creativity, and the second to the rigour, of thought. — John -

An Image of Thought Called PhilosophyOh, I'd guess you're right about Deleuze. And I like patient conceptual analyses (I'm beginning an independent study in axiomatic set theory just today). But I wish you would have responded more to "radical freedom recognizes itself joyfully in the other." Still, this was nice:

My only problem with this is that the tradition isn't alive, so we still need actual other human beings to recognize and be recognized by, admittedly through a medium like philosophy, though I would stress that this is mixed in fact with one's exposure to literature, etc. I think there are a few explosive, central realizations (radical self-possession or freedom or instrumentalism) and then lots of footnotes to be read by the fire of these realizations. The tradition, having passed on the gift, loses its aura. It's an ethical/egoistic Copernican revolution. One loves a "great" thinker (assents to this reputed greatness) only when one detects their possession of "fire." Did they hear the "laughter of the gods"? Hell, do you hear the "laughter of the gods"? I ask earnestly, in a friendly spirit. Or do you have no idea what I'm getting at and why I think the "real" meaning of any dead man's quote is quite secondary?To speak of an 'image of thought called philosophy' is the desire to feel one's (philosophical) writing 'mirrored' in the tradition, to appeal to that 'image' for recognition and continuity. — SX -

An Image of Thought Called Philosophy

Thanks for the comment. I've never studied him closely. I've picked up various books, browsed, and never really been stirred. I'd bet you're right about anxiety of influence (an important concept, along with "strong poet," with ties in D's apparent stressing of creativity.)

Seemingly related:

He says this and yet his "image of a free man" is stark-nakedly a central myth itself. I love this quote, and I'm invested myself in this idea of the radically free man or strong poet. But it's a myth or a compelling image that one shapes one's self after, like all the others, except that it's perhaps a final myth, the "creative nothing" or "hole in Being."( Stirner's book is a mess, but this same image of the free man is its beating heart.) I'm pretty committed to the idea that "spiritual urge" is always stirred and directed by usually unstable images of "the hero" or "the sacred." One idol is smashed in the name of the next. Until one acheives a sort of self-recognition as "pure negativity" or "poetic genius" (Blake) and "becomes the dragon."The speculative object and the practical object of philosophy as Naturalism, science and pleasure, coincide on this point: it is always a matter of denouncing the illusion, the false infinite, the infinity of religion and all of the theologico-erotic-oneiric myths in which it is expressed. To the question 'what is the use of philosophy?' the answer must be: what other object would have an interest in holding forth the image of a free man, and in denouncing all of the forces which need myth and troubled spirit in order to establish their power? — Deleuze

We could describe philosophy from this perspective in a high, grand way as a place where radical freedom recognizes itself joyfully in the other. This would be the "true infinite" --the negation of everything finite as lacking in genuine or sacred being -- and Deleuze one more iconoclast in its name(-lessness). But demystification can only pretend to demystify itself (for it acts in the name of the idol it would crush) or forget to notice its own, burning, superstitious center. -

Meno's ParadoxPerhaps this is relevant:

Or one could also say that "good thought" is a mode we can afford to slip into when our desperate but creative or myth-making (myth-breaking) thought has done its job and is asleepIn contradistinction to the natural goodness of thought in the traditional image, Deleuze argues for thought as an encounter: "Something in the world forces us to think." (DR 139) These encounters confront us with the impotence of thought itself (DR 147), and evoke the need of thought to create in order to cope with the violence and force of these encounters. The traditional image of thought has developed, just as Nietzsche argues about the development of morality in The Genealogy of Morals, as a reaction to the threat that these encounters offer. We can consider the traditional image of thought, then, precisely as a symptom of the repression of this violence. — IEP

till the next alarm. Heartbreak, health failure, grinding poverty: I suspect any of these move us far, far away from Meno's paradox. (Though obviously this forum is the perfect place to discuss such a thing as well as discuss the discussing of it.) -

TPF Quote Cabinet"He who despises himself nevertheless respects himself as one who despises." -- Nietzsche

-

What are you listening to right now?I just found this last night. Great, living poetry. It's called "Die." (Beanie Sigel)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aarg7gVC0TU -

Self Inquiry

It has the same tone, but it's deeper. It includes that old but beautiful thought that we are the way that the universe looks at itself, its eyes and ears -- and without which nothing. -

Meno's Paradox

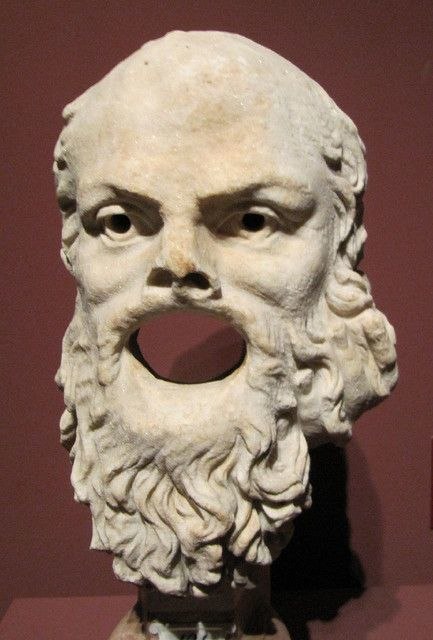

I guess the question is whether we want more than solid pragmatic knowledge and, if so, why? I have some notion of why (as a math guy), but perhaps this quest for perfect certainty (humorously) leads one to a repudiation of the original goal. As a crude analogy, we can think of philosophy as circle-squaring and post-philosophy as playful conversation opened up by an impossibility proof. Of course, this impossibility "proof" is itself just solid, pragmatic knowledge. I'd say that we end up redrawing the image of the wise-man, giving him more flesh and letting the laughter of the gods ring in his ears. But then I've been ferociously influenced by Nietzsche. As for Plato, I've only dabbled. Some of it's great, but sometimes the dialogue seems silly, stilted, slow. (The Apology is grand, of course, but I can't completely buy Socrates as hero. It's easy for an old man to throw his life away in such a grand way. A younger man doing the same thing might look like a fool to us. I hope you'll forgive this digression: I really think these gut-level attitudes are more important than we tend to acknowledge.). -

Meno's ParadoxI like the pragmatic vision of inquiry. When the machine jams, we tinker around with it until it starts humming again. Pain (among other things) spurs inquiry, which we might include as an aspect of generalized adjustment. Or we can insist that inquiry is as much about action in the typical case as it is about thought. The whole organism strives away from pain toward pleasure. Philosophers love to dwell in solitude and abstractions, so we tend to forget the typical case of social problems, physical problems. Typically, we don't completely persuade the person we have to live with. But words can be exchanged that ease the situation sufficiently so that some other tension can be addressed. With physical problems, the getting of food or warmth or aspirin, etc., also eases one tension that another may dominate problem-solving consciousness.

Addressing the first part of the OP, I'd say we always already have prior knowledge. Maybe it's not the philosopher's ideal/perfect knowledge, but it's knowledge that we do in fact act on. Pragmatism answers the skeptic in terms of the knowledge we are always already acting upon. Our belief is manifest in our doings (scepticism is largely a pose or a past-time). It half-answers the problem of ambiguity in language (dissemination or what have you) in terms of stressing the consequences of a belief. If two beliefs lead to the same actions in the relevant cases, they aren't different in an important way. (Also this insistence on action is refreshingly worldly, if one likes the image of philosophy as (street-)wise as opposed to priestly or apart.) -

Ray Monk on Wittgenstein's Philosophy of Mathematics

I like the "engineer" metaphor. It's one of my favorites. The "generalized engineer" seems to capture my current "summary" of the human mind. We solve problems, satisfy desires. Foundational quests are probably related to the "god shaped hole." Then we also desire to minimize cognitive dissonance.

I very much sympathize with this: "much of the talk about truth or 'truth conditions' that is at the heart of the traditional enterprise is 'bosh'" I wouldn't call it nonsense, but I do feel that I've had a "vision" of the futility of trying to dominate language from the outside. I want to say that "ordinary language" is the genuine metalanguage, but philosophers of a different persuasion (the very ones I'd be try to share this "insight" with) can't help but try to assimilate it in the exactly the sort of bad-math object language which is (as object language) dependent on this OrdLang. By "object language" I mean a normalized discourse, a type of communication with fixed rules (consensus) about what is "true" or "reasonable" therein. But we are always already communicating more or less successfully as we try to hammer out these nakedly secondary rules and this ideal instrument (the right system of terms of inferences) for trapping Truth. We are always already knee-deep in the meta-language, that language build and check the ideal properties of the object language we often think we need. I want to say that we are always "in fact" largely improvising, getting by on proverbs and rules-of-thumb. Generations come and go. The ideal consensus remains anything but achieved. Meaning-by-fiat is ignored away from the narrow game (futile or boring to most) of "fixing" what mostly ain't broke. Some non-philosophical problems are about language, surely, but even these are perhaps better addressed by comedians and novelists. Myths, sensual and emotional, seem to lie at the heart of the drives that employ thought. If we imagine a mind without a heart, then whether we wouldn't care whether a proposition was true or false (prudent or reckless, productive or counter-productive). But yes I get the sense that we are on the same page somehow. -

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"Just to be clear, I'm think more of this kind of instrumentalism: "a pragmatic philosophical approach that regards an activity (such as science, law, or education) chiefly as an instrument or tool for some practical purpose, rather than in more absolute or ideal terms, in particular." Except that I would certain include poems and novels among my instruments. I don't think we only move non-human nature around. We move human nature around.

-

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"

I don't know if I'd call us "finite reasoners" exactly (think philosophy of math), but I feel like you are roughly agreeing with me as if you were disagreeing. (Maybe we can figure it out). My theory is that we are hardwire, if you will, to postulate "just because" necessity. This is often called "induction." An event X is explained in terms of some necessity. It doesn't have to be sophisticated mathematically. It could be "whatever goes up must come down." This is false, of course, but it's hard to figure that out till you can give something escape velocity. And of course a sophisticated thinker can indeed experience such postulated necessity as a mere conjecture. "Maybe everything that goes up must come down." But then one might ask why must what goes up come down? So yet a more general postulation of necessity is reached for: "all matter must be (or "always" is) attracted to all matter." To simplify the situation, let's imagine a simple world where this was a theory of everything. All the laws recognized or projected by our primitive physicists can be derived from an inverse square law of gravity. The obvious question is why does the world they live in (its matter, anyway) obey an inverse square law? Because we answer such questions (in my view) in terms of postulated necessity either derived or "just-because" contingent, there is no explanation. We're out of tricks.

When you write:

The possibility of explanation implies the postulation of context, but what is the context for "everything"?

You are paraphrasing exactly the point that I made on this issue on the original PF thread (were you on that forum by chance?). Moreover, I mentioned "lyrical confusion" in the OP. I think "asinine" is a terrible word here, because I do not believe that the question is obviously "lyrical" or a "pseudo-question." If that were the case then religion and old-fashioned earnest metaphysics wouldn't be so popular, for this seems to imply that the world is massively and apparently necessarily contingent through and through, a gaping "miracle." I will grant that we can't live in this ecstatic/hysterical for long. Indeed, I can only remember the wonder I felt when I first had this vision as youth (it was my first unwittingly derivative "work" of philosophy, an ecstatic celebration of the "miracle" of empty space, color, sound, that "there was a there there.") Now it mostly supports the radical instrumentalism that I tend to embrace. No grand explanation even seems possible, if desirable in the first place. Rather than capital-T Truth, I think in terms of useful marks and noises or generalized technology, including the "technology of morale." -

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"

How would you further unpack "induction"? Noticing a pattern in experience seems creative to me, even if it's spontaneously given in simple cases.

I think I see what you mean by "self-limiting," and I tend to agree. But I still don't see why a most general theory of everything avoids its "just because" status or contingency. -

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"

I don't think you see my point at all, judging by your response. Hell, Weinberg seems to get it. He's just more interested in the explanations, while I'm interested in the concept of explanation itself. -

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"

Thanks for responding. I agree with all that you said (and I like the way you put it.) I'd just add that I really enjoy the contingency of all things as apparently revealed by analyzing explanation. I don't dwell on it often, but it's one of those beautiful perspective opened by philosophical thinking. -

Thesis: Explanations Must Be "Shallow"

I agree. That's why I stressed the creative postulation of necessity. I like Nicholas Rescher's idea of this:

"I recall well how the key ideas of my idealistic theory of natural laws - of “lawfulness as imputation” - came to me in 1968 during work on this project while awaiting the delivery of Arabic manuscripts in the Oriental Reading Room of the British Museum. It struck me that what a law states is a mere generalization, but what marks this generalization as something special in our sight -- and renders it something we see as a genuine law of nature -- is the role that we assign to it in inference."

http://www.iep.utm.edu/rescher/#H7

We project/impute necessity and check deductions against experience? This suggests that the creativity of the physicist is central. Creative imagination (in this case mathematical) is crucial. -

Social Anxiety: Philosophical inquiry into human communication

I don't think it's ignorant at all, especially if one means philosophy at its best. I think Blake was right when he called true religion the cultivation of the intellect (self-knowledge, etc.). On the other hand, religion as accusation or the obsession with an impossible and self-ignorant innocence he associated with false or anti-religion. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is just great.

Anyway, I feel very lucky and grateful myself these days ( having just turned 40) and I chalk it up to wisdom writing, which includes philosophy but also great novels and poems and films. Humans figure things out sometimes, and the best of them deeply enjoy sharing the words that help them enjoy our tour on this side of the grave. For what it's worth, you seem like a pretty aware guy at 17. I'd bet on you getting through this. My theory is that anyone who reads and writes passionately is deeply social at heart. Language is a big system of shared universal thought. It's just hard to be an "object for others." I think Sartre really nailed what was creepy in being a picture show for strangers. Maybe you're a bit hyper-aware, hyper-passionate. It could pay off in the long run. -

Is Nihilism a bad influence on a person?

I feel you. It is terrifying indeed to accept one's annihilation. I also agree that this is nevertheless the path to authenticity and depth. One reasons that what must die is largely the vessel of universal virtues that will be carried on by the next generation. If a person happens to be too alienated to see themselves in others and others in themselves, then (in my experience) they fantasize about crystallizing their irreplaceable essence in the "great work." The alienated death-dodging personality carves a copy of his misunderstood soul or likely over-rated uniqueness for some future generation worthy of him or her. When I think of my younger self, I laugh and wince and how much I (unconsciously, defensively) exaggerated my uniqueness and/or its importance. And yet one can feel wise in one's awareness of one's ignorance. And one can feel particularly attracted to the universal ,take the impersonal personally, if you will, which is to say find a real passion for it and be joyfully absorbed in it. I like the idea of the universal as a flame that leaps from melting candle to melting candle. -

''Love is a dog from Hell''

I think you nailed it right here: "Without the proper intelligence, love doesn't exist and I'm not talking about IQ or intelligence for getting good grades in school, but the intelligence related to experiencing emotions and love. "

I also think hope and trust play a central role. Hell, you have to love yourself even to believe in the love of another, to accept it. I think the word is used for a complex situation. I've been in a relationship for 20 years, now, and it is deeper and richer than ever. But it's not the same feeling that one might have toward a potential partner. That's probably for the best, for who can endure that kind of excitement indefinitely? Those jittery early feelings that obscure everything probably help us to make one of the most important choices of our lives. They force us to obsess so that in the end we can have a satisfying relationship that allows us to breath as individuals and pursue a career and profound friendships. In my view, what gets called "true love" involves building a life together. It's not just a feeling (feelings fluctuate), it's a partnership. There's a little part of you that remains alone. No one is exactly like you, so no one will ever understand you completely and utterly. But this isn't a need and in fact some ineradicable solitude has its beauty. Modern love is watching Netflix together and looking over to share a joke. Young lovers look at one another constantly. Established lovers both look out toward the world together. -

Existential Truth

There is something beautiful in Sartre. I love the idea of the self or consciousness as a hole in being. I'd call it an abstract myth that allows us to notice something about ourselves. Kojeve's Lectures on Hegel go well with Sartre. I'd say that half of Nausea is profound. The rest, upon rereading it recently, I couldn't do anything with. But there was a white flame in the little man with the lazy eye. (It's illuminating to read about his relationship with women, one in particular, with whom he gossiped and co-seduced the others).

In response to your original post, I agree with Rorty than anything and everything is re-describable. So there are not 2 ways and but countless ways to paint a situation. If there is a general structure in all of this re-description, I'd venture to say that they are all infused with purpose, desire, "bias." Reacted to another thread about "cold, hard truth," I'd say that even the notion of "cold, hard truth" satisfies a warm, soft desire. -

What the heck is Alt-Right?I've read some of a couple of their intellectuals, Nick Land and Mencius Moldbug (you can google their key works). I suppose the high-brow aspect has little to do with low-brow stuff, especially after looking at videos of that Milo character. He has a certain charisma, but he's basically absurd.

-

Is Nihilism a bad influence on a person?

Ecclesiastes is a book of wise "nihilism." It opens with "all is vanity." But it advises one to enjoy life, work hard at something one loves, find a nice girl. Childhood in this culture sets us up to expect absolutes. Maybe we are hardwired to start that way. But the pleasure in life, in all of the little projects we make for ourselves, suffices for many -- assuming there is not too much pain. And things tend to get less painful as one gets the hang of a godless life. I tempted to say something along the lines of what the wise Joseph Campbell might say: the "finite" personality has to die to make way for the "infinite" personality.

Hoo

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum