Comments

-

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyI can talk about situations that aren't in front of me. I can claim there's money in the banana stand. We can check. We can see directly whether my intention is fulfilled. — plaque flag

I think pragmatic versions of truth are inspired by a questionable imaginary perspective on communities from above. We look down on them and see their beliefs as tools. But we gaze on this vision and describe it in a 'naive' way, forgetting to apply the insight to ourselves.

A consistent pragmatist is a potentially dangerous character. Judge Holden from Blood Meridian, who takes War for his deciding god, is happy to 'argue' the finer points with you. It's also easy to imagine a sophisticated esoteric fascism. Or a 'proletarian Logic' that justifies the cost-minimized extermination of counterrevolutionaries. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyUseful fictions are far more tenacious than you're making it out, and they're tied to things that matter to people. They're practically inseparable from each other, truth and useful fiction, they're one and the same. There's no truth without useful fictions and no useful fictions without truth. — Judaka

As a former 'radical' instrumentalist and ironist, I'm open to such claims. I used to argue for them, and I still find them to be important partial truths.

But P is true is not used in the same way that P is useful to believe is used. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyI would like to hear how you understand the idea of "truth" since you've heard mine and offered no counterargument, — Judaka

I think Husserl pretty much got it right. The world is conceptually articulated. So I can talk about situations that aren't in front of me. I can claim there's money in the banana stand. We can check. We can see directly whether my intention is fulfilled. Or at least we understand the meaning of the claim in terms of such a check which may be practically impossible at the moment.

Note that there's more to this : vision isn't perfect, language can be ambiguous, ... -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyPeople disagree immensely on all the above factors, there's no consensus whatsoever. — Judaka

There's enough consensus for you to say so. 'Communication is impossible' is a performative contradiction. I know you didn't say exactly that, but you are getting close.

One can also not prove the untrustworthiness of logic. -

The Worldly Foolishness of Philosophy

That is the question. But if you say that nothing makes them true, where does that leave your claims ? Are sentences 'really' as meaningless but somehow as useful as teeth ?My statement is general and vague, and it makes claims based on creative interpretations. Are my creative interpretations true? What would make them true? — Judaka

I think you are seeing the community from the outside in Darwinian terms and forgetting your own position as a speaker about the world interpreted through this vision. The issue is whether you believe what you say, whether you really think the world is one way or another way. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyIt relates to my argument, which I established earlier on. — Judaka

I should add that I think all entities are related inferentially, so I very much embrace a certain crucial kind of relationalism (structuralism, holism).

But do our asserts 'intend' the world or not ? Beyond utility, etc. I think they do. I don't dream of denying that people can be deluded or wrong. But to be deluded is still to intend the world (empty intention) in a way that cannot be 'fulfilled.' -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyI think language needs to allow for expression of differences in perspective, — Judaka

Yes, and that of course is part of the ideal of rationality --- autonomy of the individual and of the community at large. So we work together to decide what to believe and do as a whole ---without dissolving completely into the crowd.

...He argued that human interaction in one of its fundamental forms is “communicative” rather than “strategic” in nature, insofar as it is aimed at mutual understanding and agreement rather than at the achievement of the self-interested goals of individuals. Such understanding and agreement, however, are possible only to the extent that the communicative interaction in which individuals take part resists all forms of nonrational coercion. The notion of an “ideal communication community” functions as a guide that can be formally applied both to regulate and to critique concrete speech situations. Using this regulative and critical ideal, individuals would be able to raise, accept, or reject each other’s claims to truth, rightness, and sincerity solely on the basis of the “unforced force” of the better argument—i.e., on the basis of reason and evidence—and all participants would be motivated solely by the desire to obtain mutual understanding. Although the ideal communication community is never perfectly realized (which is why Habermas appeals to it as a regulative or critical ideal rather than as a concrete historical community), the projected horizon of unconstrained communicative action within it can serve as a model of free and open public discussion within liberal-democratic societies.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jurgen-Habermas/Philosophy-and-social-theory -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyYeah, I agree, though I'm surprised to hear you say this. Isn't this the very performative contradiction you're so damning of? — Judaka

I wasn't speaking in my own voice, but from within the perspective that I am indeed criticizing. My use of 'I' was rhetorical, in other words. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyLet me reiterate that I largely agree with your take on things. So I'm just focusing on the place where we don't.

There is no "truth that exists in relation to nothing". — Judaka

To what does this truth relate ?

Let me offer something I found illuminating in my recent study of Husserl.

https://iep.utm.edu/huss-int/#SH1a

The character of an intentional act also has to do with whether it is an “empty” merely signitive intention or whether it is a “non-empty” or fulfilled intention. Here what is at issue is the extent to which a subject has evidence of some sort for accepting the content of their intention. For example, a subject could contemplate, imagine or even believe that “the sun set today will be beautiful with few clouds and lots of orange and red colors” already at eleven in the morning. At this point the intention is an empty one because it merely contemplates a possible state of affairs for which there is no intuitive (experiential) evidence. When the same subject witnesses the sun set later in the day, her intention will either be fulfilled (if the sunset matches what she thought it would be like) or unfulfilled (if the sun set does not match her earlier intention). For Husserl, the difference here too does not have to do with the content or act-matter itself, but rather with the evidential character of the intention (LI VI, §§ 1—12).

For Husserl, we can just see the plums in the icebox. But we can also intend that state of affairs from a distance (an 'empty' not-yet-fulfilled intention.) "There are plums in the ice box" is true because there are plums in the icebox --and meaningful in terms of potential fulfillment. To be sure, things get messier when concepts refer to concepts, but is our intention still transcendent ? Beyond utility ? The plums are there. And 2 + 2 =4. We can just see it, etc.

Direct realism helps here. We see the world as always already conceptually organized. I see plums and not purple balls. I see clouds and not white clumps. It's only philosophers whose theoretical analyses got us believing the world was actually reducible to pieces. Ontology is holist in its intention. But much of life is happy with useful reductive fictions or maps. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsOr else we relegate ideas to mere infectious memes. Flesh or spirit – is it possible not to choose? I'm reminded of Mervyn Peake's Mr Pye. — unenlightened

Nice link. New to me. -

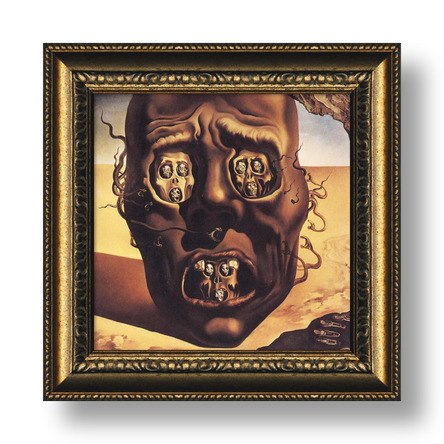

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsAs little gods, we become the architects of our fate, and time sees the realisation of our plans and ideas and dreams within the great dream which is God's Creation. And our nightmares. For little gods it is all-important to think happy thoughts. But then, talk of the real has to start to look like this: — unenlightened

As far as I can tell, your concern is that theological metaphors might lead to superstitious denials of personal death. FWIW, I think that the case in that thread for afterlife is pure sophistry, classic death-evading delusion. It's also just shallow for a philosopher to care so much about personal immortality. Our lives are ego-transcending in principle, directed toward an ideal community. This face on me, which is not so ugly, is also not so irreplaceable or important. What's worthwhile in me is pretty much what's worthwhile in everybody else.

We can't completely ignore tho the creative aspect of individuality. I may bring the tribe a gift that only I can bring. But even here I'm probably adjacent in the space of personality to others who'll bring an adjacent gift (in gift space) if I fail.

FWIW, I'm such a practiced atheist at this point that I can safely enjoy the symbols and tales that mystified my adolescence. That may be part of the charm for philosophers like Hegel --to handle those coals that once seemed so hot like tinker toys. Or to reframe that evil magic, now with both bare feet in the mud shit broken glass and flowers.

If you want a revolution

return to your childhood

and kick out the bottom -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsForgive me, the thread moves fast, and my Hegel rather Vaguel. But when God is introduced, reality is turned on its head. This world of flesh becomes the dream, and rationality and morality becomes the real. — unenlightened

To me Feuerbach is maybe the key figure here. God is roughly the projection of the species essence. You and I as individuals are small next to the infinity of the species. We are little tentacles of a giant squidlike beast with billions of such tentacles, linked through language in a kind of species-mind. One of philosophy's fundamental assumptions is the translatability of meaning ---which is to say the idea of idea itself as a flame that leaps from candle to candle, expression to expression. We both love Cantor, so I know you know what I mean.

Idea may depend on embodiment and may even be 'body' as a kind of aspect of flesh, but it's the freest and most 'contagious' part of our flesh. We are the supremely networked being --- so that private language is an oxymoron. The irreducibility of assertion hints also at a shared mind. If I trust the boy who cries wolf, I see the world through his eyes, thanks to 'ideality.' The whole tribe sees through the eyes of all its members at once. Feuerbach sees that 'Reason' has the attributes of God --- disembodied and yet subjective. But (as I've stressed in several threads) independence from any particular body is not independence from all bodies. This is where the fantasy of the independent object sneaks in.

Given that we are futural beings for whom imagined futures determine interpretation of the past and bodily action in the present, rationality and morality [hopefully] become the real in a good sense. How can I understand your own speech act except as an optimistic normative imposition ? Benevolent caution ? A push in the right direction ? -

On Illusionism, what is an illusion exactly?

Overall you seem to be saying that you are an unfree-irresponsible meatbot or the algorithm inside it. You basically claim that pain don't hurt. You also reject the founding claim-constraining normativity of rational conversation.

Try to see this pose you are offering from the outside. Why should one trust an amoral robot programmed by its environment when 'it' claims to be such an amoral robot ? 'I am a liar.' ' I don't care about truth.'

I don't mean to be rude. I'm just pointing out the strangeness of you offering your opinions with a certain confidence while eroding any possible authority or interest they are likely to have. Like a drunk at a bar, satisfying with something that sounds edgy, 'unsentimentally' numb to the lack of coherence.

To be clear, I think you do care about truth, which is to your credit. And you are just trying to see around your culture to that transcendent truth by avoiding sentimental attachment to norms that might get in the way of that truth-seeing project. Nietzchean stuff. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyPhilosophy strives to argue for the benefits of this group-orientated thinking, that we should sacrifice some of our own personal goals because if we all did that, we'd all be much better off. Philosophy also provides us with a reason to hold others accountable for their actions, and fight for the benefit of others based on blind principles.

I'd argue that's what philosophy tries to offer to the world. Holding others accountable to do what's in the best interests of the group and figuring out the best conditions for the group to exist in. — Judaka

:up:

I think overall your present a kind of group nervous system that has individual thinkers as cells. These cells are constrained by their membership in what they can and ought to say. And I pretty much agree. Though I still think there's a subtle issue in the 'feedback' of such claims. I think we intend the same kind of transcendence that such claims deny as we make them. So I earnestly assert epistemological limits and violate those limits as I assert them. That kind of thing. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyHowever, so long as philosophy, refers to the use of these biases, it's not just critical thought. If we're preaching to the group, we need to offer something the group would be interested in, and that's what philosophy is. — Judaka

If you mean it's not perfectly critical thought, then I agree. As Habermas puts it, the ideal communication community is, well, ideal. It's the perfect circle we never achieve. Rationality and justice shine on the horizon. These ideas/ideals affect us even in their 'unreality.' -

The Worldly Foolishness of Philosophy3. Truths are correct references, philosophy excludes the relevancy of most relevances, and the relevant ones have moral importance. Philosophical concepts tie back to point 1, they must be beneficial to the group. — Judaka

To me this is where your view shows some tension. Truths are correct references sounds like the assertion of truth's transcendence.

Do you believe that a community might generate a set of useful fictions ? or superstitions that are good for them in the short term ? For instance, Newtonian physics was once thought to be correct and not just an excellent approximation. People in that time were probably empowered by such a scientific triumph. Or a community might believe itself to be the center of freedom and justice on earth, even though it's mid or worse, which could help them expand their borders, since they are spreading the Best way to live.

We are in dark Nietzschean waters now questioning the will-to-truth itself. Does it not turn us back on our own intentions ? Do you understand yourself to intend truth ? To assert P looks irreducible to me. Articulation of world. -

The Worldly Foolishness of Philosophy1. Philosophy is thought for the group, logic must succeed at providing desirable conditions for the group, and arguments compete in being the best at doing this.

2. Philosophy is thought-overriding, the logics of philosophy represents a commitment to the well-being of the group, and this objective is sacrosanct. Alternative objectives aren't accepted. — Judaka

:up:

Well said. I don't 100% endorse or agree, but you point out the crucial issues. Very like Rorty again, too. Truth is what your contemporaries let you get away with saying. (Rorty). Since he got away with saying it....it must be true ?

The ethnocentric point is that we can't see around our own culture. But Rorty can't present this as a truth about human beings. Instead (for him anyway) it's only a useful tool, a speech act better understood as scratching an itch or opening a can of beans.Our vocabularies, Rorty suggests, “have no more of a representational relation to an intrinsic nature of things than does the anteater’s snout or the bowerbird’s skill at weaving” (TP, 48). Pragmatic evaluation of various linguistically infused practices requires a degree of specificity. From Rorty’s perspective, to suggest that we might evaluate vocabularies with respect to their ability to uncover the truth would be like claiming to evaluate tools for their ability to help us get what we want – full stop. Is the hammer or the saw or the scissors better – in general? Questions about usefulness can only be answered, Rorty points out, once we give substance to our purposes.

For Rorty, then, any vocabulary, even that of evolutionary explanation, is a tool for a purpose, and therefore subject to teleological assessment. Typically, Rorty justifies his own commitment to Darwinian naturalism by suggesting that this vocabulary is suited to further the secularization and democratization of society that Rorty thinks we should aim for. Accordingly, there is a close tie between Rorty’s construal of the naturalism he endorses and his most basic political convictions.

...

One result of Rorty’s naturalism is that he is an avowed ethnocentrist. If vocabularies are tools, then they are tools with a particular history, having been developed in and by particular cultures. In using the vocabulary one has inherited, one is participating in and contributing to the history of that vocabulary and so cannot help but take up a position within the particular culture that has created it. -

The Worldly Foolishness of PhilosophyPhilosophy does not have an impractical interest in truth, it's thought funnelled through a particular set of selection biases and rules which aim at creating particular moral conditions. — Judaka

I see why this view is tempting. It looks like a form of relativism. Is your own statement here trying to be true ? Or as you yourself trying to create a particular moral condition ?

This next example is not aimed at you.

Let's say a person hates the conceptual complexity of metaphysics and sees no bump in their feed for all their trouble. Aren't they motivated to embrace a relativism that denies the purity of the enterprise ? 'It's all useful fiction.' 'It's all contingently determined by our cultural inheritance.' But such claims must themselves be rationalizations or fated unfree interpretations of the world. Frankly I myself find such claims hard to deny, yet I see the logical issue, and (foolishly in worldly terms) point it out on a forum. -

Rationalism's Flat Ontologynor do I consider any humanist or rationalist ontology to meet your own criteria of not being stacked or privileging one entity over another. — Possibility

I think (I hope) that my OP made it clear that ontology itself (the stage and its ontological actors) is the necessary spider at the center of the web. The primary use of 'flat' is to emphasize the claim that 'mental' and 'physical' entities have always already been inferentially connected in order to be meaningful in the first place. [ OK, I'm not 100% an inferentialist, but ...]

This contributes toward motivating a phenomenological indirect realism which is another aspect of that flatness. Your hallucination is part of my world along with my desk lamp and . Though noninferential access to such entities may vary from person to person, with you having a privileged 'view' of your toothache, our inferential access to such entities is (ideally) 'transpersonal' (no private language, inferentialist semantics, etc.) A person born blind can know about color and yet has never seen, inasmuch as knowledge is understood in terms of justified true belief.

The 'rationalism' is not so much a nerdy celebration of 'facts and logic' as a level or moment of philosophy's dialectically achieved 'self-consciousness.' The ontologist articulates the real through/with justified claims. Small wonder then that inferential role semantics becomes so tempting. -

Entangled Embodied SubjectivityI think the difference between your position and mine (or Barad’s), though, is that we don’t believe there is an inherent distinction of the ‘subject’ - certainly not as necessarily central to the reality it articulates. There’s a ‘Copernican Turn’ of sorts required here, to decentralise language, if we are to more accurately understand reality and our role in it. — Possibility

Perhaps you are making some anti-logocentric point about 'knowing' reality nondiscursively. I readily grant that conceptuality is merely one 'dimension' or 'aspect' of a reality is also colorful and loud and feelingful and smells like beer or cotton candy. If that's the case, it's a basically Romantic point I can relate to.

But our own central contribution to the world's conceptual aspect looks hard to deny, especially given the role of thinkers in determining/articulating precisely that --- even to say such is not the case. What else could we be doing here ? And the more radical our intentions, the more radically the world's 'meaningstructure' is potentially shaken by us. -

Rationalism's Flat Ontology

Presumably you imply the relatively atemporal truth that such truth is impossible. That's the problem with lazy poses. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsJust adding a little more background to the OP.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jurgen-Habermas/Philosophy-and-social-theoryThe notion of an “ideal communication community” functions as a guide that can be formally applied both to regulate and to critique concrete speech situations. Using this regulative and critical ideal, individuals would be able to raise, accept, or reject each other’s claims to truth, rightness, and sincerity solely on the basis of the “unforced force” of the better argument—i.e., on the basis of reason and evidence—and all participants would be motivated solely by the desire to obtain mutual understanding. Although the ideal communication community is never perfectly realized (which is why Habermas appeals to it as a regulative or critical ideal rather than as a concrete historical community), the projected horizon of unconstrained communicative action within it can serve as a model of free and open public discussion within liberal-democratic societies. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling Assumptions

I've mostly studied the earliest Derrida phonocentrism-targeting stuff, focussing on passages like these:

https://monoskop.org/images/8/8e/Derrida_Jacques_Of_Grammatology_1998.pdfThe voice is heard ( understood ) ... closest to the self as the absolute effacement of the signifier: pure auto-affection that necessarily has the form of time and which does not borrow from outside of itself, in the world or in "reality," any accessory signifier, any substance of expression foreign to its own spontaneity. It is the unique experience of the signified producing itself spontaneously, from within the self, and nevertheless, as signified concept, in the element of ideality or universality. The unworldly character of this substance of expression is constitutive of this ideality. This experience of the effacement of the signifier in the voice is not merely one illusion among many -- -since it is the condition of the very idea of truth --- but I shall elsewhere show in what it does delude itself. This illusion is the history of truth and it cannot be dissipated so quickly. Within the closure of this experience, the word is lived as the elementary and undecomposable unity of the signified and the voice, of the concept and a transparent substance of expression. This experience is considered in its greatest purity--- and at the same time in the condition of its possibility -- as the experience of "being."

...

Declaration of principle, pious wish and historical violence of a speech dreaming its full self-presence, living itself as its own resumption; self-proclaimed language, auto-production of a speech declared alive, capable, Socrates said, of helping itself, a logos which believes itself to be its own father, being lifted thus above written discourse, infans (speechless) and infirm at not being able to respond when one questions it and which, since its "parent is [always] needed" must therefore be born out of a primary gap and a primary expatriation, condemning it to wandering and blindness, to mourning. Self-proclaimed language but actually speech, deluded into believing itself completely alive, and violent, for it is not "capable of protect [ing] or defend [ing] [itself]" except through expelling the other, and especially its own other, throwing it outside and below, under the name of writing. — Of Gram

This notion of the son who would be his own father is also in Joyce, and Derrida studied Ulysses.

History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

Is Derrida trying to climb out of metaphysics ?

Is metaphysics trying to climb out of writing?

Is Derrida trying to climb out of trying to climb out ?

Does a regard for metaphysics still haunt this trying to climb out of trying to climb out ? So that silence or mystic babble in a black forest hut is the best one can do ?

The thrown project says : I am the history from which I'm trying to awake. The living past in my spiritual flesh. The living past leaps ahead. The living past is my pair of eyes lost.

Sartre is worthy too.

I am my past in the mode of no longer being it.

I am my future in the mode of not being able to be it.

Speech dreams of being/becoming pure spontaneous autonomous ideality, ejecting/denying its dependence on and determination by what came before (its having been thrown?) [its enabling context] as its shadow writing. As someone else noted (random internet blog), there's some Sartre in Derrida, and we know young Derrida loved Sartre as one of his teenaged or precocious preteen heros (can't remember the bio well enough on this point.)

Man is a futile passion to be god, and Speech quests for the purity of a impossible flying nakedness. Writing represents of course deferral, ambiguity, negative elements that only signify structurally, pointing pointlessly to one another and never to the thing itself.

Derrida knew as well as anyone (White Mythology) that philosophy was oracular, mythical, metaphorical --and then that metaphoricity functioned metaphysically in such a statement and became thereby undecidable as the enabling center of a structure. I'm riffing a bit on beloved Derridean themes, but I can't help but glean 'positive' ontological theses from the work. He reminds me of a sunnier Nietzsche, and maybe he's sunnier because there was a place for him in the world. -

There Is a Base Reality But No One Will Ever Know itNot much more might be involved than a choice of ways of speaking about the unknown. — Banno

Perhaps. -

There Is a Base Reality But No One Will Ever Know itOnly realism works. — Banno

Yes. Though that still leaves some wiggle room. -

Entangled Embodied SubjectivityOn the other hand, I live as a consciousness, and that's my reality, the world began when I was born, and will end when I die. — Judaka

:up:

I'd just say that the world you live in is also my world --- but from a different perspective. The world that we can reason about together must be the world we share.

I'd need a reason to care, and some pros and cons before I could begin thinking about it. Not that I expect you to provide me with that, by the way. — Judaka

This is connected to my thread about the foolishness of philosophy. Some issues have no obvious practical relevance, and yet some of us sometimes really like trying to get clear on such issues. Maybe (I don't know) some of this could help with interpretations of theories in physics, but that's not why I do it. It's the challenge of telling the most coherent story. -

On Illusionism, what is an illusion exactly?So if I lacked autonomy I would just believe whatever you said? Are you implying that anything that lacks autonomy instead becomes perfectly obedient or amenable? — goremand

No. I'm surprised you would think that. The issue is whether you ought to believe whatever I tell you. In short, I'm trying to get you to account for the normative dimension of the project of establishing beliefs rationally.

Another way to put it: why would a person be proud of being a scientist ? of trusting science ? Why would a person be proud of living an examined life ? -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsYup! If the fascists won the war we'd be singing the same praises we sing to democracy -- the new society finally cleansed of the dirty people from the old times (something like the USA's narrative with respect to Native Americans -- we brought them technology and science and reason and God!) — Moliere

Yes. Now we optionally start walking on 'the dark side of God.' Tangent (?), but did you ever look at Blood Meridian ? Dark dark beauty.

:up:But I don't think of us as mere primates. I think of us as creatures with an ecological niche that happens to include language as an important part of that niche. And if I'm right about language it's basically the most important part of our ecological niche -- it's only because fewer of us have to die to change our ways that we are building the anthropocene (which, in turn, we are becoming aware of, will destroy us if we don't change) — Moliere

Yes, I agree that language is the killer app, a sort of extra dimension of our environment --a timebinding cultural web that we endlessly enrich (Popper's World 3, Husserl's sediment, Heidegger's One.)

I walked with ye olde serpent Rorty for a number of years. Still love the guy, though I try to catch the little rat in my foundation trap. You may know all this too well, but: He presents something like a vision endless decentralized unjustified experiment with vocabularies grasped more as teeth or ladders than pictures of reality. We also just cling to democracy for no reason at all. No deeper justification. A frank ethnocentrism. We contingently arrived here and 'irrationally' should try to protect what we like about this place. Yet he ends up celebrating the same old ideal communication community. I like Derrida too. But I tend to think the wild thinkers can only wander so far. They'll all boot out the nazi. Or any tyrant that'd shut 'em up (excepting some hard left thinkers perhaps, like maybe even my beloved Kojeve if had been given the power.) -

Entangled Embodied SubjectivityTo tell you what you already know, we have a lot of corroborating factors involved, for example, I see a table in front of me, I then reach out and I can touch it in the place I saw it, and then I put my water bottle on top of it. All of that seemingly validates my vision. Hence our ability to know about hallucinations and illusions, where corroborating factors are scarce or contradictory. — Judaka

I'm a direct realist. The world is real and we look at it and not at some representation of it. Consciousness is just the being of the world for you or me. But we are entangled with it. It's not a dream, but it's also not a thing that's part from us ---or at least I can't make sense of such a claim.

Your hallucination is real and it exists in our shared world. You just have different access to that particular entity. It's still inferentially linked to all other entities, or it'd be meaningless. No dualism needed. Different kinds of entities in the world. Toothaches are as real as pennies. You can't see my lamp. I can't see your toothache. We can both see according to our preparedness to look at it (with different intensities of understanding, because maybe one of us knows more math). -

Entangled Embodied SubjectivityCan you provide an example of an issue that convinced you to reject scientific realism? Or do you just take it to be semantically inaccurate? — Judaka

Mostly the second. Let me explain why I find it problematic. If we [try to] imagine what the world is like without us looking at it, we are just using our living brain to remember what the world looks through our human eyes while pretending we aren't there ---- but we are still there, doing the imagining.

What makes scientific realism so tempting is that we people come and go in this world that endures as a stage for this coming and going. And yet this universal stage is still, as far as we know from experience, given only perspectively ---to and through the actors on this same stage. Entangled.

The semantic issue is that we can't give any meaning to the world-in-itself that isn't stolen from the world-for-us. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling Assumptions

:up:And for the record, I am an ex-rationalist who still loves rationality. But I've come around to the idea that reason has its limits. — Moliere

I very much agree there's much more to life than this game with concepts. And there's even more to be done with concepts that 'ontology.' -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsAnother credit to Hegel is he's definitely a post-Cartesian. The rejoinder there is that his solution is worse than the original problem, but he's post-Cartesian. — Moliere

To me his genius move was to take methodological solipsism to the species level. This was implicit in Kant and Descartes because the assumption was that we all had the same kind of soul or subjectivity. But we were stuck in little bubbles. Once we are all in the same bubble, the outside of that bubble loses its meaning and necessity. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsHere's where I think we actually disagree -- what I like from Kant's project is that there are limits to reason because I don't think human beings are rational. — Moliere

Oh I very much agree that we are mostly savages ! I am extremely tempted by psychologism. It's only because it's paradoxical that I don't wallow in it. I find myself engaing in it all the time, as I think we almost have to do ---model one another as machines to be manipulated. I need the clerk to cash my check, like pulling a lever.

If we are not rational, then we cannot trust our judgment that we are not rational. I tend to think of free will as a sentimental illusion, but under the jesusbeard candycoating is the idea of responsibility, including that of keeping our story straight. So there seems to be a genuine tension between conceiving ourselves as dignified rational beings and mere primates whose beliefs are the mere outputs of goomachines. The classic challenge to relativistic irrationalism is finding a way to say that nazis are bad without universal criteria. Do we just contingently not like them and that's it ? Something like determinism with respect to our beliefs (we are just programmed by our environment in a highly complicated way that includes feedback) seems to undermine or demystify democracy, etc. So we go back to Thrasymachus. Power is knowledge. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsThe defining feature of philosophy for me is the universality of logic. We need to consider the greater repercussions beyond ourselves and beyond any single case. If I wouldn't be okay with my self-serving logic being used by others, then I must admit that I was wrong, stuff like that. If my logic doesn't best serve the group then it fails within the context of philosophy. — Judaka

:up:

Exactly. And I go on to say that we need there to be a world for us to be right or wrong about for this project to make sense. As obvious as this is, many philosophers bury us in so much illusion that they can hardly make sense of how the philosophical conversation is possible. It's sort of like hey guys you gotta keep the lamp plugged in to play checkers. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsEven the philosopher is irrational, because the philosopher is a human being who loves rationality -- but as The Symposium points out the philosopher is only philosopher in that chase rather than when the chase is consummated. — Moliere

A big theme in Kojeve too, the seeker versus the one who has found. This is why I lean on the word ontologist as a little more precise for my purpose. Our ontologist doesn't typically claim to be finished or certain. The project is to 'rationally' (and so fallibly) articulate the basic structure of reality. The ontologist is possessed by this 'scientific' ambition, is, as you say, in love with philosophy. But the ontologist exists indeed by merely being on the way. The intention is foundation and existence enough, though this intention is part of what's clarified along the way. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling Assumptions

:up:The real is absurd if you ask me. Which is why we can interpret it in so many various ways. — Moliere

Just to be clear, I'd also say the real is . It's absurd too, at least in an important sense. I might really be Schlegel's transcendental buffoon, an ironic transrational mystic, just playing the white pieces for a change. For years I mostly played the pragmatist / ironist, so it's fun to turn the board around and defend the castle of rationality, be a 'conservative.' -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsBut note I was still playing Hegel-interpreting-Kant there. There's a way in which Hegel's philosophy is entirely a priori, but it's very different from Kant's notion of synthetic a priori knowledge. Or, at least, so it seems to me. — Moliere

:up:

Kant seems to have pretty much dreamed up a meta-metaphysical 'psychology' from scratch. Hegel lets us just watch a 'system 'grow in the womb of trial and error, through various internal contradictions, stacking errors up into a spine, adding to its metacognitive vocabulary --- toward some overcoming of indirect realism.

everything depends on grasping and expressing the ultimate truth not as Substance but as Subject as well

To me consciousness is the just the being of the world from a perspective, but this world is only given perspectively. So far as we cautious philosophers can say. Mystics can say anything they want. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsIs your thread basically just saying that to play tennis we need to abide by the rules of tennis? — Judaka

So far you and I have just been unfolding the concept of philosophy. My thread is about the conditions of possibility for philosophy. In short, I claim there are certain assumptions that philosophers cannot deny without performative contradiction. Anything that makes 'tennis' possible cannot be doubted or challenged within this game of 'tennis' without absurdity.

For instance : communication is impossible.

Or : there is no world. -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsThe Matrix must be atemporal, but is there a matrix at all? I'd say that Hegel's philosophy is anti-Matrix. — Moliere

Ah but is there not an structure behind or above all of the ringing changes ?

The History of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of Freedom; a progress whose development according to the necessity of its nature, it is our business to investigate.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hi/history3.htm#III -

Parsimonious Foundationalism : Ontology's Enabling AssumptionsThat claim could not be justified by a Kantian rationality, but it can be justified in a Hegelian rationality. — Moliere

Yes, which we'd maybe both explain in Hegelian terms. For the record, I'm a liquid rationalist. The lifeworld evolves ceaselessly, and our own conceptuality is part of that evolution.

plaque flag

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum