Comments

-

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?I agree that philosophy must go deeper than empirical refutations or moral outrage - but Hitchens’s value lies precisely in the moral dimension that many technical philosophers neglect. He exposes how certain conceptions of God license cruelty and submission, and that critique operates at the level of moral phenomenology, not mere empiricism. When he asks “What kind of being would demand eternal praise under threat of hell?”, he isn’t just being cynical - he’s inviting us to examine the psychological and ethical structure of the “God-concept” itself.

You ask what is “natural” versus “supernatural.” I’d say that distinction loses meaning if “God” cannot be coherently defined or empirically differentiated from nature. Once the supernatural ceases to have observable consequences, we’re left only with human moral experience - which is precisely where Hitchens situates his inquiry: in compassion, honesty, and the freedom to question.

If “God” is a moral concept, then its worth must be judged by the moral outcomes it inspires. A concept that sanctifies fear, tribalism, or subservience fails on its own moral grounds. The greatness you mention may indeed be woven into the fabric of human existence - but perhaps what we call “God” is simply our evolving attempt to articulate that greatness in moral and existential terms. When the old metaphors harden into dogma, philosophy reopens the question.

So I’d say: philosophy doesn’t replace Hitchens’s critique - it completes it. -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you for sharing your observations. Given how self-contradictory the Bible is, I am not surprised that Christians can't agree about what is right and what is wrong.

-

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Thank you for your detailed reply.

1. On decoherence, chaos and “everything matters”

You’re right to insist that every physical event in principle influences the future state of the universe. But there are three separate claims mixed together here, and they need to be untangled:

Claim A: “Every decoherence event must produce a macroscopically different future.”*

This is false as a practical claim. Mathematically, you can map a micro-perturbation forward, but most microscopic differences remain confined beneath the system’s Lyapunov horizon and are washed out by dissipation and averaging. Saying “it mattered in principle” is not the same as “it produced a distinct, observable macroscopic outcome.”

Claim B: “If a quantum event didn’t cascade to macroscopic difference, then it didn’t happen.”

This is a category error. An event’s occurrence is not defined by whether it produces long-range, observable divergence in weather on Mars. Decoherence can and does happen locally without producing macroscopic differences that survive coarse-graining. To deny the event happened because it didn’t alter the weather is to adopt a peculiar, counterfactual definition of “happened” that isn’t used in physics.

Claim C: “Because chaotic systems amplify differences, microscopic quantum noise always matters.”

Chaos gives sensitivity to initial conditions, not guaranteed macroscopic divergence from every tiny perturbation within any fixed observational timescale. Some perturbations are amplified quickly; many are damped or trapped inside subsystems and never produce a new, robust classical structure. So yes, everything is part of the state functionally, but that does not imply practical, observable macroscopic branching for every microscopic event.

2. On ensemble forecasting and pragmatic unpredictability

Ensemble weather models show that small perturbations grow and forecasts diverge over days to weeks. That demonstrates sensitivity, not an omnipresent quantum-to-macroscopic channel that we can exploit or even detect in a controlled way. Ensemble perturbations used in practice are far larger than Planck-scale corrections; their convergence tells us about statistical predictability and model error, it does not prove ontic indeterminacy at the macroscale. In short: models are evidence of chaotic growth, not of routine quantum domination of weather.

3. Interpretations of quantum mechanics - collapse, MWI, Bohmian, etc.

Two helpful distinctions:

Predictive equivalence vs metaphysics.

Most mainstream interpretations (Copenhagen-style pragmatism, Everett/MWI, Bohmian/DBB, GRW-style objective collapse) make the same experimental predictions for standard quantum experiments. Where they differ is metaphysical: whether there is a literal branching reality (MWI), hidden variables (Bohmian), or real collapses (GRW/Penrose). That difference matters philosophically but not experimentally so far.

Determinism vs practical unpredictability.

MWI is best understood as deterministic at the universal wave function level (no collapse), while Bohmian mechanics is deterministic at the level of particle trajectories guided by the wave function. Both can produce the same Born probabilities for observable results. Objective collapse theories, if true, would introduce genuine stochastic events at the fundamental level. Superdeterminism attempts to recover determinism by postulating global correlations that undermine usual independence assumptions - but it’s philosophically and scientifically unattractive because it erodes the basis for experimental inference.

So: yes, many interpretations are deterministic; some are not. But the existence of multiple empirically-equivalent interpretations means the metaphysical verdict isn’t settled by current experiments.

4. Functional robustness (brains, transistors, computation)

Absolutely: brains and silicon devices exploit enormous redundancy and averaging to achieve robust classical behaviour despite quantum microphysics. That robustness is precisely why we can treat neurons as implementing computations without invoking exotic quantum effects. Inputs and boundary conditions matter: if an input to a brain were influenced by a huge amplification of a quantum event, your choices could track that influence, but that’s a contingent physical story, not a metaphysical proof of libertarian free will.

5. About “happening”, counterfactuals and responsibility

Two related points:

Happening and counterfactual dependence.

Whether an event “happened” should not be defined by whether it caused a macroscopic divergence millions of miles away. Physics generally treats events as happening if they leave local, causal traces (entanglement, records, thermodynamic irreversibility), not by whether they produce globally visible differences across light-years.

Responsibility and determinism.

Even if one accepts a deterministic physical description (whether classical or quantum-deterministic under MWI or Bohmian), that does not automatically dissolve ordinary moral responsibility. That’s the compatibilist position: responsibility depends on capacities, reasons-responsiveness, and the appropriate psychological relations, not on metaphysical indeterminism. Saying “my decision was set at the Big Bang” is metaphysically dramatic but doesn’t change whether you deliberated, had conscious intentions, and acted for your reason(s) - which are precisely the things our ethics and law respond to.

6. About “pondering” and the illusion of choice

You’re right to resist the crude conclusion that determinism makes choice an illusion. Choice is a process that unfolds over time; it can be broken into sub-choices and revisions. Whether decisions are determined or involve ontic randomness does not by itself answer whether they were genuinely yours. If you deliberated, weighed reasons, and acted from those deliberations, we rightly treat that as agency. Randomness doesn’t create agency; reasons and responsiveness do.

We shouldn’t conflate three different claims: (A) that micro events in principle influence the universal state; (B) that such influence routinely produces distinct, observable macroscopic outcomes; and (C) that metaphysical determinism therefore undermines agency. In practice, decoherence + dissipation + coarse-graining mean most quantum perturbations don’t make detectable macroscopic differences. Interpretations of quantum mechanics disagree about metaphysics but agree on predictions. And finally, even in a deterministic physical world, agency and moral responsibility can still be meaningful because they hinge on capacities, reasons, and psychological continuity, not on metaphysical indeterminism. -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Did you watch the above video? I agree with everything he said in the video. Please note that I am talking about the Biblical God.

Christopher Hitchens may not have been a professional philosopher, but I don’t think that diminishes the depth or value of his insights. What I find interesting about what he says about God is not technical philosophy but moral and existential clarity.

He challenges the assumption that belief in God automatically makes a person moral, and he exposes the moral contradictions in many religious doctrines - especially those that sanctify cruelty, fear, or submission. He asks uncomfortable but necessary questions: If God is good, why does he permit suffering? If morality depends on divine command, does that make genocide or slavery good if commanded by God?

Hitchens also reminds us that we can find meaning, awe, and compassion without invoking the supernatural. He combined reason, moral passion, and literary brilliance - showing that intellectual honesty and empathy can coexist.

So, while he wasn’t a technical philosopher, he was a moral and cultural critic who made philosophy accessible and urgent - which, to me, is just as important. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?

1. On Decoherence and Chaotic Amplification

I appreciate your clarification. I agree that once decoherence has occurred, each branch behaves classically. My emphasis was never that quantum events never cascade upward, but that most do not in practice. Chaotic sensitivity doesn’t guarantee amplification of all microscopic noise; it only ensures that some minute differences can diverge over time. The key is statistical significance, not logical possibility.

The fact that there are trillions of decoherence events per nanosecond doesn’t entail that every one creates a macroscopically distinct weather trajectory. Many microscopic perturbations occur below the system’s Lyapunov horizon and are absorbed by dissipative averaging. The “butterfly effect” metaphor was intended to illustrate sensitivity, not to claim that every quantum fluctuation alters the weather.

So:

Yes, chaos implies amplification of some differences.

No, it doesn’t imply that quantum noise routinely dominates macroscopic evolution.

Empirically, ensemble models of the atmosphere converge statistically even when perturbed at Planck-scale levels, suggesting the mean state is robust, though individual trajectories differ. (See Lorenz 1969; Palmer 2015.)

2. On Determinism, Ontic vs. Epistemic Randomness

You’re right that we can’t know that randomness is purely epistemic. My point is pragmatic: there’s no experimental evidence that ontic indeterminacy penetrates to the macroscopic domain in any controllable way.

MWI, Bohmian mechanics, and objective-collapse theories all make the same statistical predictions. So whether randomness is ontic or epistemic is metaphysical until we have a test that distinguishes them.

Even if indeterminacy is ontic, our weather forecasts, computer simulations, and neural computations behave classically because decoherence has rendered the underlying quantum superpositions unobservable.

So I’d phrase it this way:

The world might be ontically indeterministic, but macroscopic unpredictability is functionally classical.

3. On Functional Robustness

Completely agree: both transistors and neurons rely on quantum effects yet yield stable classical outputs. The entire architecture of computation, biological or digital, exists precisely because thermal noise, tunnelling, and decoherence are averaged out or counterbalanced.

That’s why we can meaningfully say “the brain implements a computation” without appealing to hidden quantum randomness. Penrose-style arguments for quantum consciousness have not found empirical support.

4. On Choice, Process, and Responsibility

I share your intuition that a “choice” unfolds over time, not as a single instant.

Libet-type studies show neural precursors before conscious awareness, yet subsequent vetoes demonstrate ongoing integration rather than fatalistic pre-commitment.

Determinism doesn’t nullify responsibility. The self is part of the causal web. “Physics made me do it” is no more an excuse than “my character made me do it.” In either case, the agent and the cause coincide.

Thus, even in a deterministic universe, moral responsibility is preserved as long as actions flow from the agent’s own motivations and reasoning processes rather than external coercion.

5. Summary

Decoherence → classicality; not all micro noise scales up.

Chaos → sensitivity; not universality of amplification.

Randomness → possibly ontic, but operationally epistemic.

Functional systems → quantum-grounded but classically robust.

Agency → compatible with determinism when causation runs through the agent.

Quantum indeterminacy might underlie reality, but classical chaos and cognitive computation sit comfortably atop it.

Responsibility remains a structural property of agency, not an escape hatch from physics. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Thank you for your thoughtful and technically well-informed reply. Let me address your key points one by one.

1. On Decoherence vs. Propagation of Quantum Effects

I agree that quantum coherence is not required for a quantum event to have macroscopic consequences. My point, however, is that once decoherence has occurred, the resulting branch (or outcome) behaves classically, and further amplification of that quantum difference depends on the sensitivity to initial conditions within the system in question.

So while a chaotic system like the atmosphere can indeed amplify microscopic differences, the relevant question is how often quantum noise actually changes initial conditions at scales that matter for macroscopic divergence. The overwhelming majority of microscopic variations wash out statistically - only in rare, non-averaging circumstances do they cascade upward. Hence, quantum randomness provides the ultimate floor of uncertainty, but not a practically observable driver of weather dynamics.

2. On the “Timescale of Divergence”

I appreciate your breakdown - minutes for human choice, months for weather, millennia for asteroid trajectories, etc. That seems broadly reasonable as an order-of-magnitude intuition under MWI or any interpretation that preserves causal continuity. What’s worth emphasizing, though, is that those divergence times describe when outcomes become empirically distinguishable, not when quantum indeterminacy begins influencing them. The influence starts at the quantum event; it’s just that the macroscopic consequences take time to manifest and become measurable.

3. On Determinism and Randomness in Complex Systems

I also agree that classical thermodynamics is chaotic, and that even an infinitesimal perturbation can, in principle, lead to vastly different outcomes. However, that doesn’t mean the macroscopic weather is “quantum random” in any meaningful sense - only that its deterministic equations are sensitive to initial data we can never measure with infinite precision. The randomness, therefore, is epistemic, not ontic — arising from limited knowledge rather than fundamental indeterminacy.

Quantum randomness sets the ultimate limit of predictability, but chaos is what magnifies that limit into practical unpredictability.

4. On Decision-Making Systems and Quantum Filtering

I completely agree that biological and technological systems are designed to suppress or filter quantum noise. The fact that transistors, neurons, and ion channels function reliably at all is testament to that design. Quantum tunneling, superposition, or entanglement may underlie the microphysics, but the emergent computation (neural or digital) operates in the classical regime. So while randomness exists, most functional systems are robustly deterministic within the energy and temperature ranges they inhabit.

* Decoherence kills coherence extremely fast in macroscopic environments.

* Chaotic systems can amplify any difference, including quantum ones, but not all microscopic noise scales up meaningfully.

* Macroscopic unpredictability is largely classical chaos, not ongoing quantum indeterminacy.

* Living and engineered systems filter quantum randomness to maintain stability and reproducibility.

So while I agree with you that quantum events can, in principle, propagate to the macro-scale through chaotic amplification, I maintain that in natural systems like the atmosphere, such amplification is statistically negligible in practice - the weather is unpredictable, but not “quantumly” so. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?So no, you could not have made a different choice because that would have meant that you had different information than you did when you made the decision. — Harry Hindu

I agree. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Thank you for asking for a source. You’re right that quantum effects can, in principle, influence macroscopic systems, but the consensus in physics is that quantum coherence decays extremely rapidly in warm, complex environments like the atmosphere, which prevents quantum indeterminacy from meaningfully propagating to the classical scale except through special, engineered amplifiers (like photomultipliers or Geiger counters).

Here are some references that support this:

1. Wojciech Zurek (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics, 75, 715–775.

Zurek explains that decoherence times for macroscopic systems at room temperature are extraordinarily short (on the order of (10^-20) seconds), meaning superpositions collapse into classical mixtures almost instantly.

DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.75.715

2. Joos & Zeh (1985). The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment. Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter, 59, 223–243.

They calculate that even a dust grain in air decoheres in about (10^-31) seconds due to collisions with air molecules and photons - long before any macroscopic process could amplify quantum noise.

3. Max Tegmark (2000). Importance of quantum decoherence in brain processes. Physical Review E, 61, 4194–4206.

Tegmark estimated decoherence times in the brain at (10^-13) to (10^-20) seconds, concluding that biological systems are effectively classical. The same reasoning applies (even more strongly) to meteorological systems, where temperature and particle interactions are vastly higher.

In short, quantum coherence does not persist long enough in atmospheric systems to influence large-scale weather patterns. While every individual molecular collision is, in a sense, quantum, the statistical ensemble of billions of interactions behaves deterministically according to classical thermodynamics. That’s why classical models like Navier–Stokes work so well for weather prediction (up to chaotic limits of measurement precision), without needing to invoke quantum probability.

That said, I fully agree with you that quantum randomness is crucial to mutation-level processes in biology - those occur in small, shielded molecular systems, where quantum tunnelling or base-pairing transitions can indeed introduce randomness before decoherence sets in. The key distinction is scale and isolation: quantum effects matter in micro-environments, but decoherence washes them out in large, warm, chaotic systems like the atmosphere.

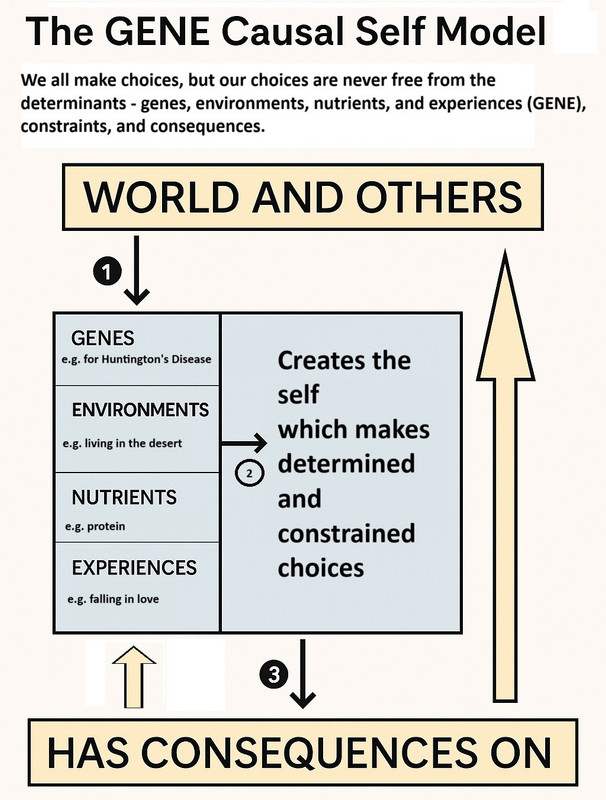

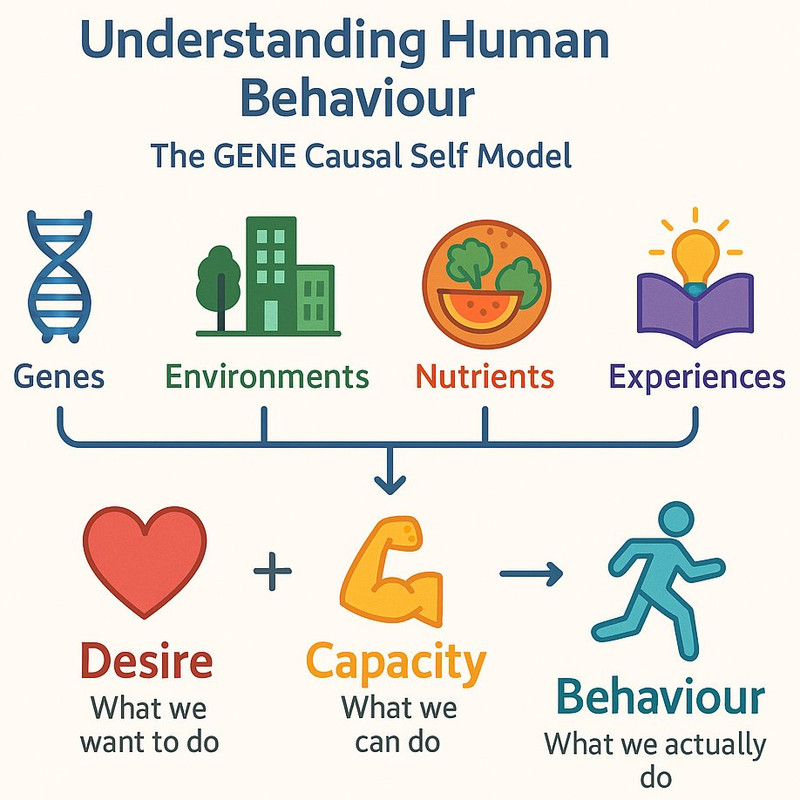

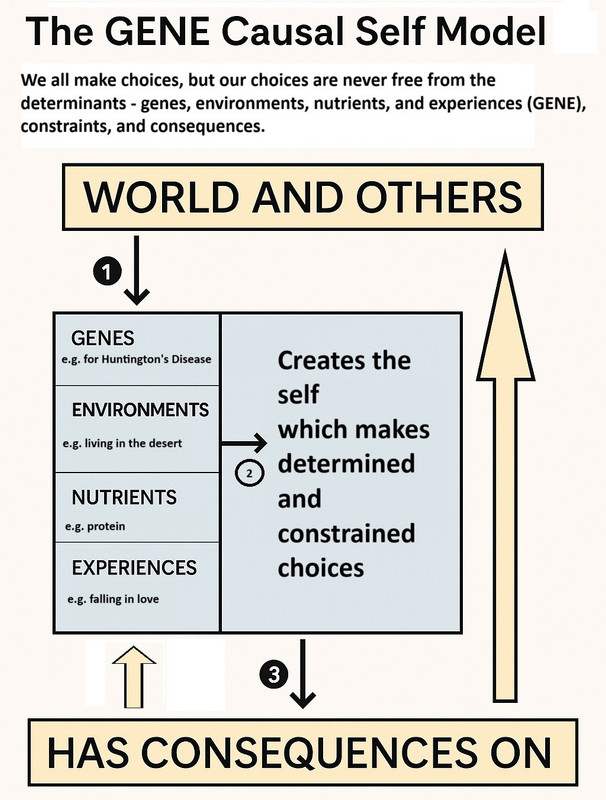

Here are two images I created to help explain my worldview:

-

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?I agree with Christopher Hitchens. Thank you very much for posting the video.

-

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Thank you very much for the fascinating links you posted. I really appreciate your thoughtful follow-up. I agree that we’re largely converging on the same view.

Regarding Norton’s dome, I think it’s an interesting mathematical curiosity rather than a physically realistic case of indeterminism. It depends on idealized assumptions (e.g., perfectly frictionless surface, infinite precision in initial conditions) that don’t occur in nature. Still, it’s a useful illustration that even Newtonian mechanics can be formulated to allow indeterminate solutions under certain boundary conditions.

As for the quantum–chaos connection, yes - Schrödinger’s cat is indeed the archetypal quantum amplifier, though it’s an artificial setup. In natural systems like weather, decoherence tends to suppress quantum-level randomness before it can scale up meaningfully. Lorenz’s “butterfly effect” remains classical chaos: deterministic, yet unpredictable in practice because initial conditions can never be measured with infinite precision. Whether a microscopic quantum fluctuation could actually alter a macroscopic weather pattern remains an open question - interesting but speculative.

I agree with you that determinism is a great tool for agency. Even if all our choices are determined, they are still our choices - the outputs of our own brains, reasoning, and values. Indeterminacy doesn’t enhance freedom; it merely adds noise.

On superdeterminism: I share your concern. It’s unfalsifiable if taken literally (since it could “explain away” any experimental result), but it remains conceptually valuable in exploring whether quantum correlations might arise from deeper causal connections. I don’t endorse it, but I don’t dismiss it either until we have decisive evidence.

You put it well: the bottom line is that we mostly agree - especially that neither pure determinism nor indeterminism rescues libertarian free will. What matters is understanding the causal web as fully as possible.

Thanks again for such a stimulating exchange. Discussions like this remind me how philosophy and physics intersect in fascinating ways. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Quantum indeterminacy is irrelevant because at macroscopic levels all the quantum weirdness (e.g. quantum indeterminacy and superposition) averages out.

— Truth Seeker

Only sometimes, but not the important times. There are chaotic systems like the weather. One tiny quantum event can (will) cascade into completely different weather in a couple months, (popularly known as the butterfly effect) so the history of the world and human decisions is significantly due to these quantum fluctuations. In other words, given a non-derministic interpretation of quantum mechanics, a person's decision is anything but inevitable from a given prior state. There's a significant list of non-deterministic interpretations. Are you so sure (without evidence) that they're all wrong?

Anyway, it's still pretty irrelevant since that sort of indeterminism doesn't yield free will. Making truly random decisions is not a way to make better decisions, which is why mental processes do not leverage that tool. — noAxioms

Thank you for the thoughtful response. You raise a key point — that in chaotic systems, even minute quantum fluctuations could, in theory, scale up to macroscopic differences (the “quantum butterfly effect”). However, I think this doesn’t meaningfully undermine determinism for the following reasons:

1. Determinism vs. Predictability:

Determinism doesn’t require predictability. A system can be deterministic and yet practically unpredictable due to sensitivity to initial conditions. Chaos theory actually presupposes determinism - small differences in starting conditions lead to vastly different outcomes because the system follows deterministic laws. If the system were non-deterministic, the equations of chaos wouldn’t even apply.

2. Quantum Amplification Is Not Evidence of Freedom:

As you already noted, even if quantum indeterminacy occasionally affects macroscopic events, randomness is not freedom. A decision influenced by quantum noise is not a “free” decision — it’s just probabilistic. It replaces deterministic necessity with stochastic chance. That doesn’t rescue libertarian free will; it only introduces randomness into causation.

3. Quantum Interpretations and Evidence:

You’re right that there are non-deterministic interpretations of quantum mechanics - such as Copenhagen, GRW, or QBism - but there are also deterministic ones: de Broglie-Bohm (pilot-wave), Many-Worlds, and superdeterministic models. None of them are empirically distinguishable so far. Until we have direct evidence for objective indeterminacy, determinism remains a coherent and arguably simpler hypothesis (per Occam’s razor).

4. Macroscopic Decoherence:

Decoherence ensures that quantum superpositions in the brain or weather systems effectively collapse into stable classical states extremely quickly. Whatever quantum noise exists gets averaged out before it can influence neural computation in any meaningful way - except in speculative scenarios, which remain unproven.

So, while I agree that quantum indeterminacy might introduce genuine randomness into physical systems, I don’t see how that transforms causality into freedom or invalidates the deterministic model of the universe as a whole. At best, it replaces determinism with a mix of determinism + randomness - neither of which grants us metaphysical “free will.” -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Randomness entails a factor not under our control. — Relativist

It's not just randomness that is a factor not under our control. We don't control the genes we inherit, our early environments, our early nutrients and our early experiences. As we grow older, we acquire some control over our environments, nutrients and experiences, but even then, we don't have 100% control.

-

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?I think both, but I'm not a compatibilist. — bert1

That's interesting. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?Even though it seems like you could have chosen differently, it is impossible to know you could have. — Relativist

I agree that it is impossible to know with 100% certainty. -

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?I agree. Faith is not reliable. Religions are self-contradictory, mutually contradictory, and they contradict what we know using the scientific method.

-

Could anyone have made a different choice in the past than the ones they made?If hard determinism is true, then all choices are inevitable, which means that no one could have chosen differently. It's impossible to know with 100% certainty whether it is true or false.

-

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you, Constance. I can see how much care you’re taking to work these ideas through, and I appreciate the way you keep tying them back to phenomenological method rather than treating them as free-floating theses.

I think I understand your point that the “wholly other” is not something that stands beyond phenomenality, but is disclosed in the radical indeterminacy of language and in the givenness of value itself. Your example of pain was helpful: the badness of the burn isn’t an “idea” but an elusive alterity that resists reduction, and only shows itself when we perform the reduction. That gives me a sense of how phenomenology preserves otherness without positing a Kantian noumenon.

At the same time, I’m still left wondering: if all alterity is revealed within phenomenality, isn’t there a risk that “the wholly other” becomes just another way of talking about indeterminacy and openness, rather than something irreducibly beyond? Levinas wanted the face of the other to resist assimilation; does phenomenology, as you frame it, secure that resistance, or does it reinterpret it as another disclosure of givenness?

On responsibility, your clarification helps. Animals and children participate in the value-dimension, but responsibility as such belongs to us, since it requires reflection and concepts. That makes sense, but I’m curious whether this creates a two-tier picture: all sentient beings are moral participants, but only humans are moral agents in the full sense. Is that the distinction you’d want to defend?

And lastly, I can see why you describe phenomenology’s refusal of closure as a strength rather than a weakness - it keeps philosophy alive, a “feast for thought.” But when you gesture toward meta-consummatory and meta-redemptive grounds, you seem to be moving back toward something like metaphysics or even theology. How do you see phenomenology avoiding the pitfalls of “bad metaphysics” at that point? Does this “metaground” remain descriptive, or does it inevitably take us into prescriptive, religious territory? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you, Constance, that was a fascinating tour through Heidegger, Levinas, Derrida, and beyond. I think I see more clearly now what you mean when you describe the “wholly other” not as something that exceeds language but as something disclosed within the indeterminacy of language and the openness of being. That does help explain why you resist the charge of collapse: otherness isn’t abolished, but appears in the play of disclosure and re-description.

Still, I’m struck by the cost of this move. If alterity is always mediated by hermeneutical openness, then the “wholly other” seems inseparable from the historical contingency of our vocabularies. Is that really sufficient to preserve what Levinas meant by alterity in the ethical sense - the face of the other as a demand that resists assimilation? Or is phenomenology reinterpreting that demand as simply another manifestation of openness?

On agency, I appreciate your willingness to extend moral significance beyond the human - that if cats and canaries participate in value-as-such, then they are owed moral regard as agents of a kind. That resonates with contemporary debates about animal ethics, though your grounding in phenomenality is very different from utilitarian or rights-based accounts. I suppose my question here is: if all sentient beings are moral agents in this descriptive sense, what still distinguishes human responsibility? Is reflection just a matter of deepening what is already basic, or does it introduce something normatively unique that goes beyond affectivity?

Finally, I notice you say phenomenology doesn’t “solve” problems but reframes them. Do you see that as a strength - a way of keeping thought open to the world as event - or as a limitation compared to traditions that do aim for closure in metaphysical answers? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you again, Constance - I can see how much thought you’ve put into this, and it helps me clarify where my own sticking points are.

On the “wholly other”: I appreciate how you bring Derrida into the discussion, especially the way language can turn back on itself and fall “under erasure.” I think I see what you mean: that when language asks “what am I?” it exposes both its indispensability and its limits, and that this tension is where the notion of the wholly other arises. Still, I find myself asking: does this really preserve alterity, or does it risk reducing “otherness” to the play of language itself? If all otherness is mediated through our historical vocabularies, can the “wholly other” ever really exceed them?

On co-constitution: your insistence that “pain is not an idea” struck me. I take you to mean that normativity doesn’t float free as some principle, but that it arises directly out of the manifestness of suffering itself. That’s a powerful point, but it does blur the line between ontology and normativity. If pain is already “its own importance,” then ethical obligation seems built into the structure of being. Do you think that means ethics is not derivative at all, but intrinsic - part of the very fabric of reality?

And regarding agency: I see now that you’re trying to resist both Kant’s formal reduction and a purely human-centered notion of agency. If even my cat evidences agency in its participation in the value-dimension, then ethics extends beyond reflection into affectivity itself. That’s an intriguing move, but I wonder: if all sentient creatures are agents in this sense, does “ethics” lose its distinctively human task of reflection and responsibility, or does reflection simply become one way of deepening what is already basic to existence? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?I like how you put it that phenomenology resists deflationary “language game” talk and instead sees all knowledge as hermeneutical, including science itself. That helps explain why you stress that suffering and value aren’t abstractions but intrinsic to the manifestness of being.

But I’m still wrestling with the issue of co-constitution. If, as you say, “pain is its OWN importance,” then ethics is not something layered on top of ontology but already woven into it. Yet doesn’t that blur the line between description and normativity? Saying “pain is its own importance” feels stronger than “pain shows up as something important to us.” Do you mean to suggest that importance is ontologically basic, that value is part of the very fabric of reality?

And on your point about agency: I find it intriguing that you see even your cat as a moral agent because it participates in the value-dimension of existence, even without conceptual reflection. That seems to broaden “agency” far beyond the Kantian framework. But does that mean every sentient creature participates in ethics simply by virtue of suffering and caring? If so, wouldn’t ethics then lose its distinctively human dimension of reflection and responsibility?

Finally, on scientific realism: if physics is just another hermeneutical abstraction from phenomenality, does it still tell us something true about the world, or is it simply a historically contingent interpretation that works until paradigms shift? I’m wondering whether, in your view, science still “latches onto” structures of reality or whether its authority is entirely instrumental. -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?So my view would be: we should avoid unnecessary harm wherever it occurs, but we must prioritize preventing the most intense and obvious suffering. And right now, that means reducing and eliminating the killing of sentient organisms when we can live well on plant-based foods.

— Truth Seeker

It sounds like you are projecting your own personal value or psychological state onto the nature and the eco system unduly and with some emotional twist. The nature works as it has done for billions of years. It operates under the system called "survival for fittest". Lions always used to go and hunt for deers, striped horses and wild boars. If you say, hey Lion why are you eating the innocent animals killing them causing them pain? And if you say to them, hey you are cruel, bad and morally evil to do that. Why not go and eat some vegetables? Then it would be your emotional twist and personal moral value projected to the nature for your own personal feel good points.

Lions must eat what they are designed to eat by nature. No one can dictate what they should eat.

Same goes for human. Human race is not designed to eat rocks and soils, just because someone tells them it is morally wrong to eat meat, fruits or vegetables because they may suffer pain, and they might have minds and consciousness.

The bottom line is that it is not matter of morality - right and wrong. It is more matter of the system works, and what is best and ideal for the nature. If it is healthy - keep them fit and keep them survive for best longevity, and tasty for the folks, then that is what they will eat. — Corvus

I think it’s important to distinguish between what happens in nature and what humans choose to do. Lions must eat other animals because they have no alternative. Humans, by contrast, have alternatives. We can thrive on plant-based diets, which are now supported by mainstream nutrition science, and in doing so, we can drastically reduce the suffering and death we cause.

Appealing to “nature” as a moral guide is tricky. Nature also contains parasites that eat their hosts alive, viruses that wipe out populations, and countless brutal struggles. If “survival of the fittest” were our moral compass, then any act of domination or exploitation (e.g. murder, torture, rape, robbery, slavery, colonization, child abuse, assault, theft, etc.) could be excused as “just natural.” But human ethics has always involved questioning our impulses and asking whether we can do better than nature’s cruelties. You used the word 'designed' for humans and lions. Humans and lions are not designed. They evolved. Evolution is a blind process, it has no foresight, plan or conscience.

So I’d say the real issue isn’t whether killing happens in the wild - it obviously does - but whether we, with our capacity for reflection and choice, should perpetuate unnecessary killing when alternatives exist. Lions can’t choose beans over gazelles. We can. That’s where morality comes in. Lions murder other lions, and they have no police or legal system to punish the murderers, but we do. Humans are not lions, and lions are not humans. We have the capacity for moral reasoning - lions don't.

Veganism is far more than a diet. It's an ethical stance that avoids preventable harm to sentient organisms. Fruits and vegetables don't suffer pain because they are not sentient. Humans, lions, zebras, deer, chickens, cows, lambs, goats, pigs, octopuses, squids, dogs, cats, rabbits, ducks, lobsters, crabs, fish, etc., suffer because they are sentient. Please see:

https://www.carnismdebunked.com

https://www.vegansociety.com/go-vegan/why-go-vegan

https://veganuary.com

-

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?I think I see what you’re saying, that what looks like a “collapse” isn’t a collapse at all, but an opening. If noumenality is internal to phenomena, then the “other” is always already available through the recontextualizing power of language. A pen is what it is until language situates it otherwise, and in that sense the “wholly other” is not shut out but emerges as a possibility.

That helps me understand why you resist the charge of collapsing appearance and reality. You’re not erasing the difference but relocating it: the difference shows up within manifestness itself, in the shifting horizons of description and re-description. The danger, you’re suggesting, only comes if we try to freeze being into a final, closed definition.

Still, I wonder whether this move really preserves the “otherness” that Kant had in mind. If all otherness is mediated by our historically contingent vocabularies, does the idea of the wholly other end up being just another name for the openness of language? In that case, are we still talking about reality-in-itself, or have we turned it into a way of describing indeterminacy within phenomenality?

And on your last point about good and bad: I find it intriguing that you see them as “closed only in their manifestness.” Do you mean that values, unlike objects, resist infinite re-contextualization, that they present themselves with an authority that can’t be deferred in the same way? If so, is that where phenomenology keeps the ethical from collapsing into pure relativism? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?

Thank you for taking the time to unpack all of that - it’s a lot to absorb, but I think I follow the thread. If I understand you, you’re saying that Kant’s noumena don’t need to be treated as some unreachable “beyond,” but rather are already immanent within phenomenality itself - the givenness of the world. The cup, the keys, the pain in my ankle: these are not mere appearances pointing to something hidden, but the very ground of what Kant misplaced on the noumenal side.

That makes sense of why you think phenomenology “drops representation” and allows the world simply to be what it is. But then I wonder: doesn’t this risk dissolving the distinction between appearance and reality entirely? If noumenality is internal to phenomena, then haven’t we just collapsed reality-in-itself into the structures of givenness, making it conceptually impossible to say what, if anything, could be “other” than appearance?

I also found your point about language important - that ontology requires articulation, and that language both makes the world manifest and at the same time gestures apophatically beyond itself. Still, I’m left with a tension: if language constitutes beings, do we have any grounds left for scientific realism? In other words, can we still say physics describes how the world is, or is it only another language-game, a historically contingent way of structuring manifestness?

And finally, on the ethical dimension: I appreciate your insistence that value is not vacuous, that pain and joy are not abstractions but intrinsic to the manifestness of being. But if value is as foundational as you suggest, does that mean ethics is not derivative of ontology, but co-constitutive with it? That strikes me as both powerful and problematic - powerful because it restores seriousness to ethics, problematic because it blurs the line between descriptive ontology and normative claims.

Would you say phenomenology ultimately abolishes the metaphysical question, or only reframes it as a question of how manifestness discloses itself in experience, language, and value? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Why wouldn't the murder of 80 billion sentient land organisms and 1 to 3 trillion sentient aquatic organisms per year by non-vegans and for non-vegans be morally wrong when it is possible to make vegan choices which prevent so much pain and death?

— Truth Seeker

Some plant and fruit lovers might say to you that how could you kill the plants pulling them out from the field, cut and boil or fry them, and eat them? You are killing the innocent living plants. Same with the corns and fruits. They were alive and had souls. But you took them from the fields, cut them and boiled them, and ate them killing them in most cruel manner. The panpsychic folks believe the whole universe itself has consciousness and souls. Even rocks and trees have mind. What would you say to them? — Corvus

That’s a fair question, and it touches on deep debates about consciousness and moral status. If plants or even rocks had experiences - if they could feel pleasure, pain, or suffering - then harming them would indeed raise moral concerns. But that’s precisely the point: sentience, not mere aliveness, is what makes the moral difference.

Plants grow, respond to stimuli, and even have complex signaling systems, but there is no credible evidence that they have subjective experiences. There is no “what it’s like” to be a carrot or a corn stalk. By contrast, cows, pigs, chickens, lambs, octopuses, and lobsters clearly display behaviors indicating pain, fear, and pleasure. That’s why I draw the moral line at sentience: it’s the capacity for suffering and well-being that generates ethical duties.

If panpsychism is true and everything has some primitive form of consciousness, then we’re faced with a spectrum: perhaps electrons or rocks “experience” in some attenuated sense. But even then, there is a morally relevant distinction between a rock that (hypothetically) has a flicker of proto-consciousness and a pig screaming in agony while being slaughtered. Degrees of sentience would matter.

So my view would be: we should avoid unnecessary harm wherever it occurs, but we must prioritize preventing the most intense and obvious suffering. And right now, that means reducing and eliminating the killing of sentient organisms when we can live well on plant-based foods. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?So this may be a collective dream. We don't know. — frank

I agree. -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?

Thank you for this rich reply. I see more clearly now how you’re situating Kant’s “noumenon” inside the fabric of phenomenality itself - turning the supposed “otherness” of reality-in-itself into what you call givenness. That does help explain why phenomenology insists that we don’t need to posit some unreachable metaphysical substrate; the phenomenon is already the site of verification.

But here’s where I still feel some tension. If noumena are reinterpreted as “the mystery of appearance,” are we actually dissolving the distinction between appearance and reality, or are we simply redescribing it in a way that keeps philosophy “within the field” of what is given? In other words: does phenomenology abolish the metaphysical question, or only defer it?

Your remarks on emergence were also illuminating. I like the idea that “all is equi-derivative,” and that paradigm shifts in science are themselves a kind of metaphorical emergence. Still, I’m left wondering: if all emergence is intra-paradigmatic and metaphorical, doesn’t that undermine the very notion of an independent reality that science aims to describe? Physics then becomes not so much about “what the world is” but about “how our descriptions evolve.” That seems coherent, but it sounds close to a kind of conceptual idealism.

So maybe my question back to you is: do you think phenomenology, in the end, commits us to giving up on scientific realism as a metaphysical claim? Or is there still room in your view to say that physics, while mediated by paradigms, does latch onto structures of the world that exist whether or not we describe them? -

What is real? How do we know what is real?There's no criteria for testing which of your experiences are of something real and which are false, for instance, drug induced, right? — frank

You may be right that there’s no absolute criterion. Every experience, whether sober perception or drug-induced vision, arrives through the same subjective channel. The difference is usually practical rather than metaphysical: some experiences cohere with others in stable, intersubjective ways, while others clash and collapse under scrutiny. But that coherence doesn’t prove we’ve accessed “reality itself,” only that we’ve settled on a framework that works for human purposes.

In that sense, the line between “real” and “false” experiences may be fuzzier than we like to admit. What we call “real” might just mean “reliably integrated into our form of life,” while “false” means “fails to integrate.” That’s not proof that reality-in-itself is off-limits, but it does suggest that our ordinary tests are pragmatic rather than metaphysical. -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Why wouldn't the murder of 80 billion sentient land organisms and 1 to 3 trillion sentient aquatic organisms per year by non-vegans and for non-vegans be morally wrong when it is possible to make vegan choices which prevent so much pain and death?

-

What is real? How do we know what is real?

Thank you, that’s a really thoughtful response. I like your idea that “reality-in-itself is not a thing” but rather a way of speaking about aspects, limits, and frontiers. The pulsar example is helpful, because it shows how what seems mysterious and “beyond us” can eventually be integrated into our conceptual framework without invoking any separate ontological realm.

Still, I wonder: if we treat “reality-in-itself” as simply “what resists explanation until new concepts arrive,” doesn’t that risk reducing it to nothing more than the horizon of human cognition? In that case, the notion stops doing the metaphysical work Kant meant for it, and becomes more of a pragmatic placeholder. Do you think that’s an adequate way to interpret the tradition, or is something lost when we set aside the stronger claim that something exists independently of our ways of knowing?

On your last point, I agree that philosophers often overgeneralize. But if “reality-in-itself” and “being-in-itself” are different, as you suggest, how would you articulate the difference without collapsing one into epistemology and the other into ontology? What criteria let us say: “this is about reality” vs. “this is about being”? Or is the best we can do to recognize that the distinction is heuristic rather than hard and fast? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Is there any way to know for sure what is right and what is wrong?

— Truth Seeker

Observations on the circumstances with evidence, reasoning and logical analysis on the case are some tools we can use in knowing right and wrong. — Corvus

Vegans say that veganism is right and non-veganism is wrong. Non-vegans say non-veganism is right and veganism is wrong. They can't both be right. How do we decide whether veganism is right or wrong? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you for the detailed response. I think I follow your point that science always already operates within experience, and that perception is not an afterthought to objects but inseparable from them - the “perception-of-the-peak IS the peak.” That’s a powerful corrective to the picture of brains as if they were somehow standing outside of experience, receiving inputs like a machine.

But here’s what I’m struggling with: if everything reduces to the playing field of experience, how do we avoid collapsing into a kind of idealism? You say it’s not “all in the head,” but once we deny any perspective outside experience, what secures the distinction between the cup itself and my experience of the cup? Isn’t there a risk that “ontological foundations” become just redescriptions of phenomenology?

Also, I’m not sure I fully grasp your critique of emergence. You suggest that calling subjective experience an “emergent property” is incoherent, because everything we can talk about is an emergent property. But doesn’t that simply mean “emergence” is a relational notion? Temperature emerges from molecules, but molecules emerge from atoms, and so on. If experience emerges from brain states, why isn’t that just one more layer in the same explanatory pattern, rather than a category mistake?

In other words, does your view amount to saying: experience is foundational, and any talk of emergence must be subordinated to that? If so, what does that mean for scientific realism? Can we still say that physics tells us something true about the world, or only that it gives us a useful way of describing how experiences hang together? -

What is real? How do we know what is real?I appreciate your honesty about not being entirely sure what “reality-in-itself” means - that’s partly why I asked the question, since the term itself is slippery. Kant framed it as noumenon, that which exists independently of our forms of cognition. But, as you point out, every example we can give (light spectra, bird magnetoreception, etc.) still relies on human conceptual frameworks to describe it. So maybe “reality-in-itself” always risks being a placeholder for “what we don’t yet know how to grasp.”

Your examples show how science extends perception beyond its native limits, which suggests that even if we begin with projection, careful cross-checking can reveal where we’ve mistaken appearance for reality. Still, I wonder: do those successes give us reason to think we are asymptotically approaching reality-in-itself, or only that we are continually refining the human image of the world?

On the second issue, I like your thought that “reality does not equal existence.” That helps explain why “reality-in-itself” and “being-in-itself” might not be identical. The first emphasizes the independence of what is (an epistemic concern: what exists beyond our categories?), while the second stresses sheer givenness without relation (an ontological concern: what is apart from consciousness?). Perhaps they are two faces of the same riddle, but one seen through the lens of knowing, the other through the lens of being.

Do you think it’s coherent to maintain that these distinctions are useful heuristics even if, in practice, we can never step outside cognition to test them? Or do you lean toward collapsing them into a single problem about how language points beyond itself? -

What is real? How do we know what is real?That’s an intriguing way of putting it. If I understand you right, you’re linking “real” not so much to existence as to coherence - something is real if it has logical grounding, even if it is radically unlike our ordinary world.

That makes me wonder, though: does “logical grounding” mean internal consistency within a system, or correspondence with the structures of our actual world? A toon world might be internally consistent but still disconnected from what we ordinarily call reality. Similarly, “magic” in a fantasy novel can follow strict rules (e.g. conservation of energy in a different form), but is that “real,” or just “fiction with rules”?

Maybe the crux is whether logical grounding alone is enough for reality, or whether we also need some bridge to empirical verification. Otherwise, couldn’t we end up calling any consistent fiction “real” in its own frame, even if it has no existence beyond the story? -

What is real? How do we know what is real?That’s a thoughtful response. I like your framing of limits not as static barriers but as moving frontiers that expand with discovery. It raises for me two further questions.

First, when you suggest that “partly” knowing reality-in-itself implies that we do in fact know something of it, what safeguards do we have against simply projecting structures of our cognition outward and mistaking them for reality? Kant, for example, would say phenomena always bear the stamp of our categories, so even our best science may be telling us more about how our minds structure experience than about things-in-themselves. How do we tell the difference?

Second, you asked how “reality-in-itself” differs from “Being-in-itself.” For me, “reality-in-itself” gestures toward what exists independently of any observer, while “Being-in-itself” (to use Sartre’s term) connotes the sheer presence of things apart from consciousness. They might overlap, but one emphasizes ontology, the other epistemology. I’m curious: do you see them as distinct, or just two ways of naming the same riddle? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Thank you for laying this out. I see what you’re doing - pulling back from all cultural and contextual frames to speak about suffering as a pure phenomenon, rooted in Being itself.

But I struggle with your claim that suffering is ‘inherently auto-redemptive.’ From my perspective, suffering simply is. A burn, an illness, a grief - they happen, and they devastate. Calling them ‘auto-redemptive’ risks sounding like a metaphysical gloss over lived harm.

If suffering is inherently what ‘should not be,’ as you say, then how is it redeemed simply by being recognized as such? Recognition does not stop the pain, nor prevent the recurrence. Children still die, animals are still slaughtered, injustices still multiply. If the redemption isn’t concrete - if it doesn’t reduce or relieve suffering - can we honestly call it redemption at all?

It seems to me that redemption requires change in the world, not just reinterpretation of phenomena. Otherwise, aren’t we just sanctifying the very thing that cries out to be abolished? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?Humans and all the other living things are physical things. We are all made of molecules. Our subjective experiences are produced by the physical activities of our brains.

— Truth Seeker

But a thought is not a thing, nor is an anticipation, a memory, a sensory intuition, a pain or pleasure; caring is not a thing. These constitute our existence. — Constance

That’s a good point - experiences like thoughts, pain, anticipation, and caring aren’t 'things' in the same way molecules or neurons are. But they do seem to be processes or states that depend on things. For example, pain isn’t a molecule, but it is a state produced by particular neural firings and pathways. Pain relievers are also molecules that physically intervene to relieve the subjective experience of pain.

So perhaps the relationship is like this:

Physical things (neurons, molecules) provide the substrate.

Subjective experiences are emergent properties of those physical interactions.

Calling experiences ‘not things’ doesn’t necessarily make them non-physical - it may just mean they belong to a different level of description. The same way 'temperature' isn’t a molecule but arises from molecular motion.

I’m curious how you see it: do you think subjective experiences point to something beyond the physical, or are they just a different way of talking about physical processes? -

What is right and what is wrong and how do we know?a human being never was a physical thing...was it? — Constance

Humans and all the other living things are physical things. We are all made of molecules. Our subjective experiences are produced by the physical activities of our brains.

Truth Seeker

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum