Comments

-

Comparing religious and scientific worldviewsThank you very much for your reply and the link.

-

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

I do understand your position, and I think the disagreement is now very clear.

You are saying, in effect:

1. If we accept God’s omnipotence and omniscience, we must also accept God’s omnibenevolence.

2. “Perfect love” and “perfect knowledge” may be radically unlike human love or knowledge.

3. Therefore, judging God by human moral intuitions is illegitimate.

4. The proper intellectual posture is apologetics (interpretive charity), not moral critique.

I understand that view. I reject it — not out of arrogance, but because it empties the concepts being defended of their content.

Here’s why.

1. If “perfect love” is unconstrained by moral content, it becomes meaningless.

You say I cannot judge what “perfect love” is because my notions of love are imperfect.

But then we face a dilemma:

Either “perfect love” retains some continuity with what we mean by love, or it does not.

If it does retain continuity, then concepts like care, non-instrumental concern, and aversion to unnecessary harm remain relevant. In that case, the presence of involuntary suffering is morally probative.

If it does not retain continuity — if “perfect love” may will or permit anything whatsoever — then the word love no longer distinguishes God from a tyrant or a force of nature. It becomes a label without criteria.

In other words:

If divine love cannot be morally assessed in any way recognizable to moral reasoning, then calling it “love” does no explanatory work.

That is not humility. That is semantic insulation.

2. Accepting omnipotence and omniscience does not force acceptance of omnibenevolence.

You ask:

Why accept omnipotence and omniscience but not omnibenevolence?

Because power and knowledge are descriptive capacities; love is a normative property.

We infer power and knowledge from effects.

We infer goodness from moral coherence.

If an agent’s actions systematically violate what “love” means even in its most abstract form — care for the wellbeing of others — then the inference to omnibenevolence fails, even if power and knowledge are granted.

This is not criticizing a book for being a different book.

It is questioning whether the book’s internal claims are consistent.

3. Apologetics is not neutral “criticism”; it presupposes the conclusion.

You say that once we accept the omni-attributes, our responsibility is apologetics, not condemnation.

But apologetics is not neutral interpretation. It is defensive harmonization — a method that treats contradiction as something to be explained away rather than examined.

That is a legitimate theological practice.

It is not a neutral epistemic one.

Truth-seeking allows conclusions to be revised.

Apologetics does not.

Refusing apologetics is not ignorance; it is methodological independence.

4. Appeals to centuries of apologetics do not answer the logical problem.

You suggest my position reflects ignorance of Christian apologetics.

Even if that were true (and it is not to the extent implied), it would be irrelevant unless those apologetics resolve the logical issue.

But the problem of suffering has been debated for centuries precisely because no consensus resolution exists. The diversity of theodicies — free will, soul-making, mystery, greater good, fallen world — signals unresolved tension, not settled clarity.

Appealing to the existence of many responses is not the same as showing that anyone succeeds.

I should correct a factual assumption.

I have read many Christian apologetics — including works by C. S. Lewis (The Problem of Pain, Mere Christianity, Miracles, etc.). I am not unfamiliar with the tradition, and I am not dismissing it out of hand.

I reject those arguments after engaging with them, not because I am unaware of them.

My rejection is not based on temperament, resentment, or lack of literary sensitivity. It is based on a substantive judgment that none of the standard theodicies resolve the core problem — they relabel, deflect, or appeal to mystery, but they do not remove the incompatibility I’ve identified.

To be explicit:

Appeals to mystery suspend moral reasoning rather than answer it.

Appeals to greater goods rely on unproven necessity.

Appeals to divine transcendence drain moral terms of content.

Appeals to authority replace argument with deference.

I understand why apologetics aims at reconciliation rather than critique. But truth-seeking does not obligate me to adopt apologetics as a method — especially when I judge the arguments to fail on their own terms.

So the disagreement here is not about whether I’ve “done the reading.”

It is about what counts as a satisfactory explanation.

I am willing to let cherished claims fail if they conflict with moral coherence.

You are willing to preserve them by revising how moral concepts apply.

That difference is philosophical, not personal — and reading more apologetics would not change it.

5. “God knows better” is not an argument; it is a veto.

You imply that divine superiority blocks moral critique.

But once “God knows better” is allowed to override all moral evaluation, then no possible world could ever count against divine goodness — not even a world of maximal cruelty.

At that point, goodness is no longer a property we understand; it is whatever God does.

That is not reverence — it is moral quietism.

6. Why this is not hubris.

Hubris would be claiming certainty, infallibility, or moral omniscience.

I claim none of those.

My claim is conditional and conceptual:

If a being is perfectly loving, perfectly powerful, and perfectly knowing, then certain kinds of involuntary suffering are incompatible with that combination.

That is not arrogance.

It is conceptual consistency.

Refusing to surrender moral reasoning in the face of authority is not pride; it is the minimum condition of ethical thought.

You are comfortable grounding goodness in mystery and authority.

I am not.

You are willing to let “perfect love” float free of moral constraints.

I am not.

Those are different epistemic commitments, not differences in temperament or education.

Calling logical analysis “hubris” does not resolve the issue — it simply relocates it behind reverence.

I think we’ve reached the genuine stopping point: not because the issue is exhausted, but because our standards for what counts as an explanation differ.

7. How the Bible fails.

Astronomy & Cosmology: pre-scientific mythology

The Bible reflects an ancient Near Eastern cosmology, not hidden advanced knowledge:

Flat or dome-covered Earth (the firmament)

Waters above the sky

Sun, moon, and stars placed inside the firmament

Earth established before stars

Light existing before light sources

This isn’t “metaphor misunderstood later.”

It’s exactly what you’d expect from pre-astronomical humans with no telescopes, no physics, no cosmology.

A being who created galaxies would not accidentally endorse Bronze Age sky myths.

Physics: magical causation and category errors

Biblical physics routinely violates conservation laws, thermodynamics, and basic causality:

Matter appearing without physical mechanism

Instantaneous global floods

Heat, light, and motion without sources

Supernatural suspension of physical regularities without constraints

These aren’t exceptions explained by deeper laws.

They are storytelling devices, indistinguishable from myth.

Biology: creationism and biological impossibilities

The Bible gets biology wrong in structural ways:

Fixed “kinds” instead of common descent

Humans formed separately from animals

No understanding of genetics, evolution, extinction, deep time

Global bottlenecks that would have destroyed biodiversity

This is not a matter of missing details.

It reflects zero awareness of how life actually works.

Ethics: tribal morality, not universal compassion

Biblical ethics are deeply inconsistent and often morally indefensible:

Genocide endorsed

Slavery regulated, not abolished

Women treated as property

Children punished for ancestral sins

Infinite punishment for finite “belief errors”

These are not moral heights we failed to reach.

They are moral baselines we have since outgrown.

The best ethical moments in the Bible come from humans pushing against its own framework, not from divine command.

History: legendary development, not eyewitness rigor

The Bible fails basic historical standards:

Anonymous authorship

Decades-to-centuries-late composition

Theological agendas driving narrative

Contradictory accounts

No contemporary corroboration for central miracles

What we see is exactly what we see in myth formation everywhere else:

oral tradition → embellishment → canonization → dogma.

The pattern matters more than any single error

Any one mistake could be excused.

But the Bible fails:

astronomy,

physics,

biology,

ethics,

and history,

systematically, in the same direction, at the same level, with the same cultural fingerprints.

That pattern is diagnostic.

It looks exactly like what it is: a collection of human texts written by sincere but ignorant people trying to explain the world before science existed.

Why this matters morally

I care about reducing suffering and death, not about defending meaning or tradition.

That’s crucial.

Texts that:

misdescribe reality,

misassign blame,

moralize ignorance,

and sanctify error,

don’t just fail intellectually — they cause harm.

Religious certainty built on false premises has:

justified violence,

delayed medicine,

stigmatized illness,

excused cruelty,

and obstructed progress.

Rejecting that isn’t nihilism.

It’s ethical seriousness. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

I do understand your position, and let me show that before explaining why I disagree.

You are not claiming that suffering is good in itself.

You are not denying that much suffering is tragic.

You are not saying humans are competent to judge the full moral calculus of reality.

What you are saying is roughly this:

1. The traditional “omni-” attributes may be idealisations rather than strict requirements.

2. A god who is extremely powerful, extremely good, and extremely wise may still permit suffering for reasons beyond human understanding.

3. Given our epistemic limits, humans are not well placed to judge the moral decisions of a vastly superior being. What you are saying matches the following from the Bible.

"For my thoughts are not your thoughts,

neither are your ways my ways, declares the Lord.

For as the heavens are higher than the earth,

so are my ways higher than your ways

and my thoughts than your thoughts." - Isaiah 55:8,9, The English Standard Version of the Bible.

4. Therefore, the existence of suffering does not decisively count against the existence of such a god.

I understand that position. I simply do not accept it.

Here is why.

1. Weakening the attributes weakens the claim being defended

Once omnipotence, omniscience, and omnibenevolence are treated as approximate rather than defining, the argument changes category.

At that point, the claim is no longer:

“Suffering is compatible with a maximally perfect being.”

It becomes:

“Suffering is compatible with a powerful but morally and cognitively limited being.”

I agree with that.

But that concession matters.

A being who is less than all-knowing may permit suffering through ignorance.

A being who is less than all-powerful may permit suffering through inability.

A being who is less than all-loving may permit suffering through indifference, prioritisation, or malevolence towards some and benevolence towards others.

None of those cases raises a logical problem.

The problem of suffering arises only for a being claimed to be unlimited in power, knowledge, and love. Once those are relaxed, the incompatibility dissolves, but so does the traditional claim of moral perfection.

That is not a refutation of my argument; it is a retreat from its target.

2. “God knows better than you” dissolves moral reasoning itself

You ask whether it is possible that God knows better than I do.

Of course it is.

But notice what follows if that move is accepted without constraint.

If “God knows better” is sufficient to justify any amount of involuntary suffering, then no possible state of the world could ever count against God’s goodness — including worlds of maximal cruelty.

At that point, “good” no longer has content accessible to moral reasoning. It becomes whatever God does.

That is not humility; it is moral abdication.

Reasoned moral judgment does not require certainty or infallibility. It requires only this minimal principle:

If an action would be morally unjustifiable for any being we understand, then claiming it is justified for a superior being requires reasons — not appeals to superiority.

Otherwise, goodness becomes indistinguishable from power.

3. Moral superiority cannot exempt one from moral evaluation

You ask: Who are we to judge our moral superiors?

But moral superiority does not exempt an agent from moral standards — it presupposes them.

We routinely judge:

parents who knowingly allow preventable harm to children,

leaders who permit suffering for alleged long-term benefits,

institutions that justify harm by appeal to higher purposes.

We do this because we take morality seriously, not because we think ourselves omniscient.

If the concept of “good” is meaningful at all, then it must constrain even the most powerful agent. Otherwise, it is empty praise. God must follow consistent moral principles to be moral. Might does not make right.

4. This is not hubris; it is conceptual clarity

You say I appear to think I have morality “figured out.”

I do not.

I am making a far more modest claim:

Certain kinds of involuntary suffering are morally incompatible with perfect love combined with perfect power and knowledge.

That claim does not require complete moral knowledge — only consistency in the concepts being used.

Calling that “hubris” mistakes logical analysis for arrogance.

It is not arrogant to say:

a perfectly loving being would not require involuntary suffering as a condition of worth,

a perfectly powerful being would not face tragic trade-offs,

a perfectly knowing being would not rely on pain as a pedagogical tool.

It is simply to take those attributes seriously.

5. Where we ultimately part ways

You are comfortable saying:

“We must muddle through; God knows better; the rest is mystery.”

I am not.

Not because I think I am superior to God — but because once mystery is allowed to override moral coherence, nothing meaningful remains of moral praise or blame.

If suffering, injustice, and death are all compatible with supreme goodness by definition, then goodness ceases to guide understanding. It becomes a label applied after the fact.

I respect that you find religious narratives, myths, and theological humility meaningful. I am not attacking that.

I am saying that once the attributes of God are weakened, the logical problem dissolves — but so does the claim of moral perfection. And once moral judgment is surrendered entirely to inscrutability, the word “good” loses its anchor.

That is the disagreement.

It is not resentment, not biography, not hubris.

Just incompatible starting points.

I’m content to leave it there. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

First, a clarification that matters.

My argument is not Dawkins’s or Hitchens’s argument.

It is not rhetorical, psychological, or rooted in contempt for religion. It is a logical incompatibility argument.

The existence of suffering, injustice, and death is incompatible with the existence of a being that is simultaneously all-loving, all-knowing, and all-powerful.

That claim stands or falls on logic, not temperament, biography, or literary sensibility.

1. On fortitude and logical necessity

You write:

Fortitude is logically impossible without suffering.

That is correct by definition, but the conclusion you draw from it does not follow.

You then argue:

If the positive value of fortitude is greater than the negative value of suffering, a benevolent God would allow suffering.

This introduces a moral calculus — but that calculus is already incompatible with classical theism.

Why?

Because an all-powerful being is not constrained to trade-offs.

If:

God is omnipotent → no limitation on possible good.

God is omniscient → no uncertainty about outcome.

God is omnibenevolent → no willingness to impose harm.

then God is not forced to choose between:

suffering + fortitude

and

no suffering + no fortitude

That dilemma exists only under constraint.

A God who must allow involuntary suffering to obtain moral good is not omnipotent in the relevant sense.

2. “Greater good” requires necessity, not productivity

Your argument depends on this hidden premise:

Suffering is necessary for fortitude.

But necessity is doing far more work here than you’ve justified.

It is not enough to say:

“fortitude wouldn’t exist as defined without suffering”

You must show: no morally equivalent or superior good could exist without involuntary suffering.

And that is precisely what you cannot show — because an omnipotent being defines the space of possibility.

If suffering produces virtue only because the world was designed that way, then the designer is responsible for that dependency.

Productive ≠ necessary.

Occasioning ≠ justifying.

3. Love, heartbreak, and equivocation.

You say:

Love inevitably leads to suffering.

This is an empirical generalization about human psychology, not a metaphysical truth. Not all romantic relationships break up. Although everyone dies, death is not mandatory - protected immortal jellyfish don't die. God could have made all living things immortal.

Even if we grant "Love inevitably leads to suffering" for humans as we are now, it does not follow that:

love is logically inseparable from suffering, or

an omnibenevolent, omniscient and omnipotent creator could not instantiate love without grief.

Otherwise, heaven becomes incoherent — unless you concede that:

either love in heaven is diminished, or

suffering still exists in heaven.

The Bible clearly portrays the Christian heaven as a place without any suffering and death. "He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.” - Revelation 21:4, the English Standard Version of the Bible. So, the Biblical God is capable of creating a place that does not have any suffering and death. Why not make Earth free from all suffering and death?

You accuse me of dismissing heartbreak and grief as suffering. I have not.

I distinguish:

existential vulnerability (sadness, loss, disappointment)

from

imposed, non-consensual, destructive suffering (disease, torture, starvation, dementia).

Collapsing that distinction is what allows the “greater good” argument to slide unnoticed from tragedy into justification.

4. The arsonist exception exposes the problem

You write:

None of this excuses the arsonist… for humans causing suffering is immoral because we lack omniscience and our acts are motivated by hatred.

But this exemption proves the opposite of what you intend.

If:

causing suffering is wrong because humans are not omniscient,

then omniscience becomes a moral solvent — suffering becomes permissible once one “knows better.”

That collapses morality into authority.

Worse, it implies that:

if a human were omniscient,

causing involuntary suffering could become morally good.

That is not a defense of divine goodness — it is a redefinition of goodness as whatever the powerful permit.

Besides, the Biblical God commands genocide and supports slavery in the Bible. I have quoted these verses in a previous post, so I won't quote them again. Genocide and slavery are not ethical.

5. Moral worth without instrumentalization

Your view implies this structure:

suffering is allowed

because it produces virtues

which God values.

That treats persons as means to the production of virtues.

But moral agents are not raw material for character-polishing.

If a being’s suffering is justified only because it produces a value for someone else (including God), then that being’s intrinsic worth has already been subordinated.

An all-loving being would not need to trade sentient suffering for virtue creation.

6. On Dawkins, Hitchens, and “axes to grind”

You have grouped me with Dawkins and Hitchens even though my argument is different from their arguments. You really need to grasp the nuance because my argument is not theirs.

Dawkins focuses on explanatory redundancy,

Hitchens focused on institutional harm,

I am making a modal incompatibility claim.

Whether or not you enjoy myth, literature, or religious symbolism is irrelevant to that claim.

7. Final clarification

I am not arguing:

that courage is bad

that love is worthless

that suffering never leads to growth.

I am arguing that:

1. Involuntary suffering is not morally justified by the virtues it sometimes occasions.

2. An omnipotent being would not require suffering to instantiate moral good.

3. Therefore, the existence of suffering, injustice, and death is logically incompatible with the existence of an all-loving, all-knowing, all-powerful God.

That conclusion does not depend on anger, bitterness, or disdain for religion. Besides, not all religions have a creator God, e.g. Buddhism and Jainism don't have a creator God the way Christianity and Islam do. I am convinced that all religions are man-made and there is no all-loving, all-knowing, and all-powerful God because such a God would not create a world full of suffering, injustice, and death.

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?"

— Epicurus. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

You’ve now sharpened your claim, which is good. Let me respond just as precisely.

Courage is admirable.

Suffering is tragic.

The first does not sanctify the second.

Where we disagree is here:

“It might justify it.”

That is the hinge — and it does not hold.

1. Fortitude does not justify suffering; it presupposes it.

You are correct about the definition: fortitude is courage in the face of pain or adversity. But that tells us something important — and often overlooked:

Fortitude is a response to suffering, not a justification for its existence.

From the fact that fortitude cannot exist without adversity, it does not follow that adversity is therefore justified, intended, or morally acceptable.

By analogy:

Firefighters are admirable.

Fires are tragic.

The existence of firefighting virtue does not justify arson, faulty wiring, or preventable fires.

Virtue arising under constraint does not morally license the constraint.

2. Athletic pain is voluntary; cancer is not.

Your athlete analogy quietly switches moral categories.

An athlete:

chooses discomfort,

controls the risk,

can stop at any time,

accepts pain instrumentally for a self-chosen goal.

A person dying of cancer:

did not choose to have cancer,

cannot opt out of having cancer,

bears pain and death imposed by biology.

These are not morally comparable situations.

Voluntary hardship can be meaningful. It's great to train and win gold at the Olympics. It's not great to suffer and die from cancer or torture or earthquake or arson or any other fatal condition.

Involuntary suffering cannot be justified by outcomes it later occasions.

That distinction is foundational to ethics.

3. “God values fortitude” does not justify imposed suffering.

For someone who claims not to be religious, you bring up God a lot in your arguments. Why is this? Were you religious in the past? Do you wish there were a God?

You suggest that:

A benevolent God might see the fortitude of someone bravely dying of cancer as unspeakably noble.

Even if that were true, it does not follow that the suffering was justified.

At best, it would show that something admirable can arise despite the suffering.

But if God could have produced virtue without requiring cancer or any other terminal condition, and

chose cancer or any other terminal condition anyway, then the suffering remains morally unexplained.

To justify suffering, it must be shown to be necessary, not merely productive.

4. “Necessary for certain virtues” is not the same as “necessary in principle.”

Here is the key distinction your argument collapses:

Given our current world, some virtues arise only under adversity.

In principle, an omnipotent creator is not bound by our developmental constraints.

If fortitude exists only because suffering exists by design, then the designer is responsible for that dependency. With omniscience and omnipotence comes omniculpability.

Appealing to definitions (“fortitude requires adversity”) merely restates the problem — it does not resolve it.

5. Rewards after suffering do not retroactively justify it.

You say:

“For the Christian, the rewards to the sufferer might make it all worthwhile.”

But compensation is not justification. Also, the Bible says that the Biblical God predestined who would be saved and who would be damned to eternal torture in hell. Predestining sentient beings to eternal torture is fundamentally the greatest evil ever. Yet, Christians still praise this utterly evil God of Christianity!

If someone were tortured and later compensated, we would not say the torture was therefore justified. We would say the compensation mitigates the harm it does not morally license the act. If suffering is justified only after the fact, it was not justified at the time it was imposed.

6. The deeper issue: instrumentalizing persons.

Your position implies this structure:

Suffering is permitted because it produces virtues that are valued by God.

That treats persons as means to the production of virtues.

But moral agents are not virtue-factories.

They are beings whose suffering matters in itself.

If virtue requires involuntary suffering to be brought into existence, then the moral cost has not been answered — only aestheticised.

I am not denying that:

people can be admirable in suffering,

courage in adversity is real,

dignity can exist even in tragedy.

I am denying that:

suffering is justified because of the virtues it occasions,

a morally perfect creator would require involuntary suffering as a precondition for moral worth,

definitions of virtues settle moral questions about harm.

Fortitude is admirable.

Suffering remains tragic.

And tragedy does not become justified because something noble can grow in its shadow. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

You say I ascribe arguments to you that you have not made, so let me reset and respond only to the two claims you now explicitly endorse.

1. On the claim that the “scientific worldview” is limited.

Of course it is limited. I have never claimed otherwise.

Science does not answer questions of:

ultimate meaning,

moral value,

aesthetic worth.

But what science does do — and this is the point you keep trying to bracket off — is identify, explain, and reduce suffering and death in the real world. When claims are made about what is necessary, inevitable, or unavoidable in sentient life, science is directly relevant, because those are empirical claims about the world.

When someone says:

“Suffering and death are simply part of life — that’s just the sentient condition”

science answers:

“Large portions of what was once thought inevitable have already been reduced or eliminated.”

That is not worldview overreach. It is factual correction.

Calling this “harping” does not make it irrelevant.

2. On the claim that God might prefer suffering + virtue over the absence of both.

This is the real disagreement, and we should keep it here.

You suggest that:

Since some virtues are impossible without suffering, an omniscient God might rationally prefer a world with suffering and virtue to a world with neither.

That position has three problems.

(a) It assumes suffering is a necessary precondition for virtue.

That is not established.

Courage, compassion, kindness, and love may sometimes arise in response to suffering, but that does not show they are logically or metaphysically impossible without it. It only shows how we, given our constraints, tend to develop them.

An omniscient and omnipotent being is not constrained by our developmental limitations.

If a virtue requires suffering because the designer made it so, then the designer remains responsible for that requirement. What about those who just die through suffering, e.g. being tortured to death or slowly starving to death during a famine or a pig kept confined in a factory farm and slaughtered?

(b) It treats suffering as instrumentally justified.

If suffering is permitted because it produces virtue, then suffering becomes a means to an end.

That has moral consequences.

On that view:

the child who dies painfully of disease,

the animal tortured in confinement,

the person with dementia,

are not merely unfortunate — they are essential components of a value-producing system.

You may find that conclusion uncomfortable, but it follows directly from the position.

(c) It collapses omniscience and omnipotence into moral necessity.

An omniscient, omnipotent God would not face trade-offs of the form:

“Either virtue with suffering, or neither.”

That is a limitation, not a necessity.

If suffering is required for virtue, then either:

God lacks the power to create virtue without suffering, or

God values suffering itself, not merely virtue.

Either way, the appeal to omniscience and omnipotence does not rescue the claim. Besides, with omniscience and omnipotence comes omniculpability.

On “science” vs “scientific worldview”.

You say:

Medical and technological advances are the result of science — not the scientific worldview.

This is a distinction without practical force.

Science is not value-neutral in application. It is motivated by the conviction that:

suffering is bad,

death is worth postponing,

ignorance should be replaced by understanding.

Those commitments are precisely what I am defending.

You can call that a “worldview” or not — the label is irrelevant. What matters is that refusing to treat suffering as morally sacrosanct is what produces progress.

I am not arguing that:

suffering never leads to growth,

courage never arises from hardship,

the world can be made totally perfect by humans.

I am arguing that:

suffering is not justified by the virtues it sometimes occasions,

suffering is not necessary in principle for virtue,

reducing suffering is a moral good even if it can never be completely eliminated.

That position is consistent, compassionate, and fully compatible with acknowledging limits. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

All living things suffer and die. That is the "sentient condition"… We can avoid suffering and death only by avoiding living. — Ecurb

Non-sentient organisms (e.g. plants, bacteria, etc.) do not suffer, but they do die. Only sentient organisms (e.g. humans, octopuses, antelopes, cows, etc.) suffer and die.

From

“All living things suffer and die”

you infer

“Therefore rejecting suffering and death means rejecting life itself.”

That inference is false.

Reducing suffering is not the same as eliminating all suffering.

Postponing death is not the same as denying mortality.

By your logic:

Medicine is pointless.

Safety engineering is foolish.

Public health is delusional.

Yet science and technology have already:

1. More than doubled the average human lifespan.

2. Eliminated entire categories of suffering (smallpox, polio in many regions).

3. Drastically reduced infant and maternal death.

If your argument were sound, none of this would make sense. Biological immortality already exists in organisms like the immortal jellyfish. All we need to do is engineer all organisms to be immortal. Then we can spread out to other star systems, galaxies and even universes.

So the question is: should we obsess about avoiding suffering, or should we try to maximize joy?

This is a false dichotomy.

Avoiding suffering and increasing joy are not opposites — they are usually aligned.

People enjoy life more when:

they are not in chronic pain,

they are not starving,

they are not being tortured,

they are not prematurely dying.

You present harm reduction as “obsession” only because you treat suffering as morally trivial once it is common.

Falling in love is joyful, but inevitably leads to heartbreak.

Heartbreak is not the kind of suffering under discussion.

You keep sliding between:

existential disappointment (which is unavoidable), and

severe, imposed harm (which is often avoidable).

This equivocation is doing all the work.

The suffering I oppose includes:

factory farming,

starvation,

torture,

preventable disease,

premature death.

Not “sadness because a romantic relationship ended.”

Obviously, if we can cure diseases, great. It's a short-lived stay, though. We are all going to die.

This move is rhetorically neat — and morally empty.

“Yes, we cured disease, but everyone dies anyway” is exactly the argument someone could have made before antibiotics, vaccines, or sanitation.

And it would have been wrong then, just as it is wrong now.

Lengthening life, improving health, and reducing suffering are not negated by eventual death.

Otherwise, saving a child’s life would be meaningless because the child will die someday — a conclusion no sane ethic accepts.

On veganism (the point you keep evading)

You say:

“All living things suffer and die — that’s life.”

But here is the difference you refuse to acknowledge:

Vegans do not cause avoidable suffering and death to sentient beings for pleasure or convenience.

Non-vegans do.

That is not rhetoric. It is a material fact.

Factory-farmed animals are:

bred into confinement,

mutilated,

distressed,

slaughtered young.

This suffering is not inevitable. It exists because of non-vegan choices.

When demand drops, production drops.

When production drops, suffering and death drop.

That is saving and improving lives, whether or not you find it emotionally satisfying to acknowledge.

Your claim that “fewer animals would be born” somehow negates this is incoherent.

Non-creation is not harm. Creating beings for suffering is.

On science and technology (another evasion)

You concede:

“If we can cure diseases, great.”

But you refuse to draw the obvious conclusion:

Curing disease, extending life, and reducing suffering are precisely what rejecting suffering as ‘just life’ looks like in practice.

Science does not “accept the human condition.”

It systematically examines it and improves it.

Every medical advance is an act of moral rebellion against what once seemed inevitable.

Eve chose knowledge and pain over ignorance and pleasure. Are we sure she made a bad choice?

This is fiction, not an argument. There is no evidence for the existence of Adam and Eve, or for their eating from the Tree of Knowledge.

Knowledge does not require:

factory farming,

torture,

preventable disease,

mass premature death.

You keep romanticising suffering by tying it to symbolic narratives — Eden, virtue, knowledge — while ignoring the actual, concrete suffering being imposed on sentient beings right now.

Rejecting suffering is not rejecting knowledge.

It is rejecting the idea that harm is a morally acceptable price of existence.

You keep saying:

“That’s life.”

I keep showing:

life has already been radically improved by refusing to accept suffering and death as fixed,

veganism measurably reduces suffering and premature death of sentient organisms,

science and technology have saved and improved billions of lives.

Calling this “foolish” does not refute it.

It just reveals an attachment to resignation over responsibility and compassion.

I do not deny that suffering and death currently exist.

I deny that their existence justifies causing more of them — or treating efforts to reduce them as naïve.

Wanting all living beings to be forever happy is not foolish.

It is the same moral impulse that created medicine, which saves and improves lives. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

Well, yes it does mean rejecting the entire condition, since suffering and death are universal portions of the human condition. — Ecurb

No — universality does not equal essentiality in the sense you are using it.

Your basketball analogy fails because rules are constitutive by definition: if you remove them, the game ceases to be basketball. Suffering and death are not rules of life; they are contingent outcomes of biological and physical constraints. They are facts about how life currently unfolds, not definitional requirements of what life is.

To reject cancer is not to reject biology.

To reject slavery is not to reject society.

To reject suffering and death is not to reject the sentient condition.

You are reclassifying limitations as normative necessities. That is a philosophical mistake.

Almost everyone "opposes" suffering and death. So what? Opposing them is meaningless and irrational. Accepting them is rational.

This conflates recognition with endorsement.

Yes, most people say they oppose suffering — yet many actively cause massive, avoidable suffering while defending it as “normal,” “natural,” or “necessary.” Acceptance becomes rationalisation the moment it excuses preventable harm.

I do not merely dislike suffering in the abstract. I structure my life around minimising the suffering I cause, including to non-human sentient beings. That practical commitment is exactly what distinguishes opposition from lip service.

Acceptance of inevitability is rational.

Acceptance of avoidable harm is not.

You have "saved sentient lives" by becoming a vegan? I've "saved sentient lives" by refraining from murdering people.

This is a false equivalence.

You are comparing refraining from an act you were never socially permitted to commit (murdering humans) with refraining from acts that society actively normalises, rewards, and industrialises (breeding, exploiting, and killing animals).

Veganism is not moral inaction. It is refusal to participate in a system explicitly designed to cause suffering and death to sentient beings.

That distinction matters.

If more people became vegans, fewer animals would be raised, and there would be fewer "sentient lives". That constitutes "saving"?

Yes — because non-creation is not harm.

Preventing a sentient being from being bred into guaranteed confinement, mutilation, psychological distress, and premature death is not “killing a life before it begins.” It is preventing a harm from ever being imposed.

A being who is never created does not suffer deprivation.

A being who is created for exploitation does.

Conflating the two collapses the moral difference between preventing harm and ending an existing life — a difference that every coherent ethical system recognises.

It's reminiscent of your earlier claim that you wish you had never been born.

If I had never been born, I would never have suffered and died, I would never have made any mistakes and I would never have caused any harm to anyone. So, there are many positive aspects to never being born. However, if I had never been born, I wouldn't have been able to save and improve all the lives I have saved and improved.

To say “a world without imposed suffering would be better” is not to say “existing beings should not exist.” It is to say that existence under coercive harm is morally worse than existence without it.

I want sentient beings to exist without being forced to suffer and die — not to kill those who already exist.

But aren't all deaths "premature"? Death is a fact of life.

Again, fact is being confused with justification.

That all deaths occur does not mean all deaths are equally acceptable, nor that preventing early or violent death is incoherent. Medicine, safety engineering, law, and public health all rest on the distinction between avoidable and unavoidable death.

If “death is a fact of life” were a sufficient moral answer, we would abandon resuscitation, surgery, vaccines, and emergency care.

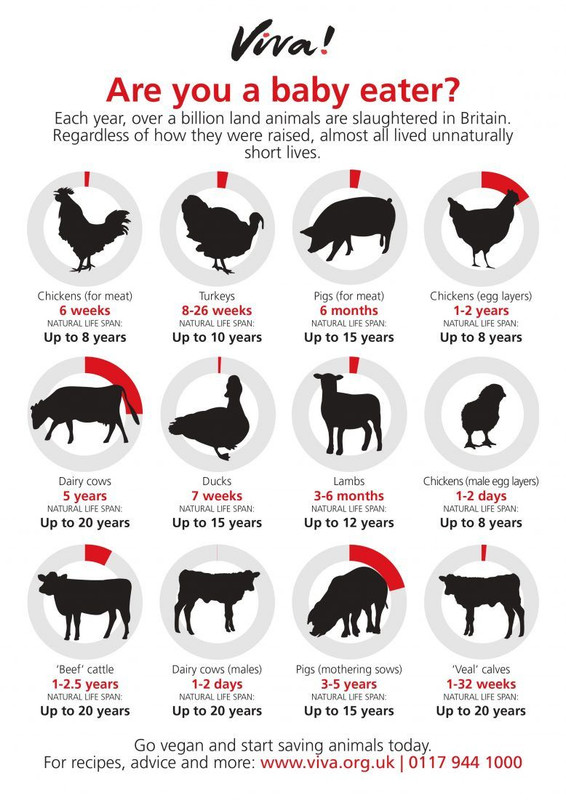

The image shows how non-vegans dramatically reduce the natural lifespan of the animals they kill. This is entirely avoidable by going vegan.

I have also saved human lives by donating blood regularly since I was 17. I save human lives also by donating money and volunteering regularly.

Humans used to live on average only 30 years in the pre-1800s. Now, they live on average 80 years in the developed countries. Science and technology have also increased the human standard of living and quality of life enormously.

Immortal jellyfish can already live forever if protected from illness, injury, starvation and predation. If we genetically engineer humans and other species to do the same, all species could live forever. I know we don't have the technology to do that yet, but scientists are working on improving our technology.

What if suffering begets moral ennobling? Isn't fortitude one of the virtues?

Fortitude is admirable in response to suffering.

That does not mean suffering is justified because it sometimes produces fortitude.

This is the same error repeated throughout: mistaking adaptive virtues for moral endorsements of the conditions that necessitate them.

We admire firefighters. We do not, therefore, endorse arson.

Virtues developed under constraint do not retroactively sanctify the constraint.

But death and suffering cannot be eliminated. It's not possible.

Impossibility is not an argument against moral orientation. As the image above shows, non-vegans dramatically shorten the natural lifespan of many sentient organisms.

80 billion sentient land animals and 1 to 3 trillion sentient aquatic organisms are murdered by non-vegans per year. This is entirely avoidable by going vegan.

We cannot eliminate all injustice — yet justice remains meaningful.

We cannot eliminate all disease — yet medicine remains rational.

We cannot eliminate all suffering — yet reducing it remains obligatory.

My position is not utopian incoherence. It is harm-minimisation grounded in moral seriousness, extended consistently to all sentient beings rather than selectively to humans.

You treat suffering and death as conceptually defining, and therefore morally untouchable.

I treat them as tragic constraints, to be resisted, reduced, and never glorified.

That difference does not make my view “negative.”

It makes it compassionate, consistent, and action-guiding.

And yes — I want all living beings to be forever happy.

The fact that this is unattainable does not make it irrational.

It makes it a moral north star. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

Suffering and death are part of the human condition. You are contradicting yourself. — Ecurb

No contradiction is present.

Suffering and death are parts of the human condition — they are not the whole of it.

Likewise, they are parts of the sentient condition more broadly.

What I reject is the slide from:

“Suffering and death are part of the condition.”

to

“Therefore, rejecting suffering and death means rejecting the entire condition.”

That inference does not follow.

Love, joy, curiosity, creativity, attachment, play, empathy, learning, and care are also part of the human and sentient condition. My objection is selective and principled: I oppose the harmful components, not the existence of sentient life itself.

Opposing disease does not mean despising biology.

Opposing injustice does not mean despising society.

Opposing suffering and death does not mean despising sentient existence.

If you regret being born, why do you object to dying? That makes no sense.

It makes sense once coercion and harm are kept in view. According to the Bible, death is not the end - it is the beginning of eternal torture in hell for those predestined by the Biblical God to be non-Christian.

I do not “regret being born” in the sense of wishing harm upon myself or others. I object to the non-consensual imposition of suffering, injustice and death on all sentient beings — including myself.

Death ends suffering by destroying the sufferer. That is not a solution; it is a termination. Wanting suffering to end is not the same as wanting the subject of experience to be annihilated. If the subject is terminated, the subject can't be happy.

To be clear:

• I want suffering to end without ending the ones who suffer.

• I want life without coercive suffering, injustice and death.

Those are morally coherent positions.

However, suffering is not preventable, nor is death avoidable.

This confuses current limits with moral ideals.

That something is not yet fully preventable does not mean it is not partially preventable, nor does it absolve us of responsibility to reduce it wherever possible.

By this reasoning, medicine, public health, law, and disaster prevention would all be meaningless.

As a vegan Compassionist, I act on this principle consistently:

I avoid causing unnecessary suffering to sentient beings, and I work to save and improve lives — human and non-human alike. Unlike non-vegans, I do not treat avoidable harm as morally acceptable merely because it is common.

I have saved and improved many sentient lives. That fact alone refutes the claim that my position is purely “negative.” The word "vegan" was coined in 1944. 82 years later, only an estimated 1% of the 8.27 billion humans currently alive are vegan. This is deeply depressing. Veganism is better for human health, for the environment and for the animals, but despite this fact, most humans have not yet gone vegan.

This is not "unjust" by any reasonable definition of justice.

Justice concerns how harms and benefits are distributed and imposed.

When harm is avoidable by going vegan yet imposed anyway, justice becomes relevant.

Much suffering inflicted on sentient beings is not inevitable. It is a product of choices, systems, and traditions. Calling that “just the way things are” does not make it morally neutral.

Good grief… Eternity is metaphorical and relative.

If “eternal life through descent” is metaphorical, then it should be acknowledged as such. In my previous post, I addressed both literal and metaphorical interpretations of your words.

Metaphors can console. They do not alter biological reality, nor do they redeem mortality itself. Each individual still suffers and dies as an individual. Symbolic continuity does not undo that fact.

You continue to tout your negative ethos. Life is horrible!

This is a caricature.

My position is not “life is horrible.”

It is: life contains enormous, unnecessary, and avoidable suffering — and that suffering matters morally.

I affirm life strongly enough to want it without cruelty, without injustice, and without premature death.

I want all living things to be forever happy — not because I hate life, but because I value sentient experience so deeply that I refuse to romanticise its harms.

Why not make the best of it?

I do my best constantly to save and improve all sentient lives.

Making the best of the world does not require pretending it is already good enough. It requires reducing harm, expanding care, and refusing to baptise suffering as morally ennobling. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

Our disagreement: you despise the human condition, I don't. You think each birth is a tragedy, and, of course, you are right. But that tragedy is redeemed by the possibility of virtue… — Ecurb

This misrepresents my position, so let me correct it plainly.

I do not despise the human condition.

I despise suffering, injustice, and death — wherever they occur, in all sentient beings, human and non-human alike. That's why I am a vegan. Vegans cause much less suffering, injustice, and death to sentient beings than non-vegans.

That distinction matters.

What I reject is not humanity, but the forced imposition of terror, pain, and death on beings who did not consent to any of it. That is not a uniquely human issue. It is a condition shared by animals, children, and every sentient organism dragged into existence without choice.

Calling this “the human condition” does important rhetorical work — it normalises what is, in fact, a universal moral catastrophe.

Terror, pain, and death are forced on all of us. That's the human condition.

Exactly — they are forced.

And it is precisely because they are forced that I object to them.

To describe this as merely “the human condition” does not explain or justify it; it only renames the problem. Injustice does not cease to be injustice because it is universal. If anything, universality deepens the moral urgency.

If a system guarantees that every sentient being will suffer and die, then the correct response is not reconciliation but moral protest.

That tragedy is redeemed by the possibility of virtue: of courage, fortitude, kindness, and love.

This is where we fundamentally diverge.

Virtues that require suffering in order to exist are not redemptive — they are adaptive responses to harm. Courage presupposes danger. Fortitude presupposes adversity. Compassion presupposes suffering.

I value kindness and love deeply — but I reject the claim that they justify the conditions that make them necessary.

If a child must be exposed to terror, pain and death so that courage may later emerge, then courage has been purchased at an unacceptable price.

The birth of a child — tragic though it may be — is also the occasion of love.

Yes, love emerges — and it does so despite the conditions imposed on that child, not because of them.

Loving someone who will inevitably suffer and die is not evidence that the system is good. It is evidence that humans — like other sentient beings — are capable of profound attachment even under tragic constraints.

Love does not retroactively justify a world structured around unavoidable harm.

So no — I do not despise the human condition.

I despise the fact that sentient beings are forced into existence, forced to endure suffering, and forced to die — and then told that the virtues developed in response somehow redeem the coercion itself.

My moral intuition is simple and consistent:

• If suffering were preventable, it should be prevented.

• If injustice were removable, it should be removed.

• If death were avoidable, it should be avoided.

If I could go back in time and prevent all suffering, injustice, and death, and make all living beings forever happy, I would do so without hesitation — not because life lacks value, but because life without imposed harm would be infinitely better.

That is not contempt for the human condition.

It is compassion extended to every sentient being, without exception.

A factual clarification on “eternal life through descent”

You write that “every child is born to grant eternal life to his or her parents (through descent).”

Taken literally, this is not biologically correct.

Having children does not make parents immortal — neither personally nor genetically.

A child inherits only half of each parent’s chromosomes. In the next generation, that contribution is halved again, and so on. After a small number of generations, any given ancestor’s genetic contribution is vanishingly small, statistically diluted, and often entirely absent due to recombination and lineage extinction.

So even on purely naturalistic terms, descent does not confer anything resembling eternal life. At most, it offers a partial, temporary, probabilistic genetic continuation, not persistence of the person, their consciousness, their experiences, or their identity.

If “eternal life” here is meant symbolically rather than biologically, then it should be acknowledged as metaphor — not presented as a literal redemption of mortality. Metaphor may offer meaning, but it does not undo death, nor does it negate the fact that each individual still suffers and dies as an individual.

In short:

• Parents die.

• Their children die.

• Genetic dilution continues.

• Nothing eternal is achieved through descent.

Whatever value love, memory, or legacy may have, they are not immortality, and they do not cancel the reality of mortality or the suffering and injustice that precede death.

You could argue that even though individual organisms die, species survive, but at least 99.9% of all the species that have existed on Earth are already extinct, and the remaining 0.1% are also at risk of extinction and will probably go extinct sooner or later.

A brief response to the Christian redemption framing

You invoke a Christian parable in which birth, suffering, and mortality are redeemed by love, descent, and salvation. I understand the existential comfort this narrative provides, and I don’t deny its emotional power. But comfort and moral justification are not the same thing.

From my perspective, redemption that occurs after imposed suffering does not morally redeem the imposition itself. A system does not become just because it later offers meaning, forgiveness, or eternal compensation to those it first exposes to terror, pain, and death without consent.

If a child must suffer in order for others to learn love, or must die in order for salvation to acquire meaning, then the moral problem has merely been reframed, not resolved.

Christianity interprets love as salvific — and I respect that internal coherence. But I reject the idea that love requires suffering as its precondition, or that suffering is morally licensed because it can later be redeemed. Love that emerges despite suffering is admirable; suffering that is justified because it produces love is not.

In short:

Redemption may console those already harmed.

It does not justify the harm itself.

My objection is not to love, meaning, or virtue — it is to a worldview that treats unavoidable suffering and death as acceptable entry fees for them.

You should remember that the Bible also provides eternal torture in hell for those predestined by the Biblical God to go there. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviewsIf we value courage or adventure, suffering is a necessary evil — Ecurb

What about those who don't want to be courageous or adventurous? Should terror, pain and death be forced on them? I think it is totally unethical to force sentient beings into situations where they suffer and die when they didn't ask to be in those situations, e.g. dying slowly in a famine, being tortured to death, being gang raped and beaten to death, being imprisoned and slaughtered in a factory farm, etc. Life imposes catastrophic costs on sentient beings without their consent. I didn't ask to be born as a human being. I wish I had never existed. Sadly, I can't kill myself without causing suffering to others. So, I am trapped in my constant suffering in a world full of suffering, injustice, and death. Life is fundamentally unethical. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviewsThank you for your reply. Have you read "Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder" by Richard Dawkins? If not, I recommend that you read it.

-

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

1. God, courage, and the design vs response distinction

You say:

“It would be reasonable for a benevolent God to value courage, fortitude, and adventure. Since pain and danger are necessary if these virtues are to exist God might have created a world in which there are pain and danger.”

This sounds plausible — but it relies on a quiet equivocation that keeps doing the work.

There are two very different claims:

1. Courage requires the possibility of danger and loss.

2. Courage requires the existence of large-scale, involuntary, preventable suffering.

(1) is true.

(2) does not follow.

A world can contain:

risk,

uncertainty,

vulnerability,

moral difficulty,

genuine stakes,

without containing:

childhood cancer,

torture in the name of religion or ideology,

mass predation engineered into biology,

the genocide of one tribe by another,

natural disasters killing millions,

the mass extinction of 99.9% of all the species that have existed on Earth,

extreme suffering and slaughter imposed on those who didn't consent, e.g. factory farm animals.

Courage is a response virtue, not a design justification.

A benevolent designer could value courage without embedding vast quantities of non-consensual suffering into the fabric of reality. Saying “God might have done it this way” is not an explanation — it’s a permission slip.

And crucially:

You don’t need this move at all, because you’ve already said you’re not religious.

2. The “benevolent God” hypothesis adds nothing explanatory

Notice what invoking God does not do here:

It doesn’t tell us how much suffering is necessary.

It doesn’t tell us which beings must suffer.

It doesn’t explain why suffering is distributed so arbitrarily and unevenly.

It doesn’t explain why courage in one being requires agony in another.

“All this suffering exists because courage is valuable” is not an explanation — it is post hoc aestheticization.

If someone said:

“Perhaps a benevolent God values music, so He created tinnitus,”

we would immediately see the non sequitur.

Same structure. Same flaw.

3. Science, measurement, and the Whitman mistake

You write:

“Surely a ‘scientific worldview’ sees the world in measurable terms.”

No.

It sees some aspects of the world in measurable terms — when measurement is the right tool.

This is the core misunderstanding that keeps resurfacing.

A scientific worldview says:

The moisture content of air is measurable.

The mystical feeling Whitman describes is real as experience. The neural activity underlying our experiences can be observed in real time using fMRI and PET scanners. However, we don't have the capacity to experience what it is like to be another sentient being e.g. you don't know what it is like to be me, and I don't know what it is like to be you, or a bat, or a whale, or a chicken, etc.

What it rejects is this leap:

“Because an experience is meaningful, it can overrule facts about the world.”

Whitman’s “mystical moist night-air” is not threatened by science unless one commits to scientism, which neither I nor any serious philosopher of science is defending.

Whitman is reacting to explanatory saturation, not to truth.

He leaves the lecture because wonder returned, not because the astronomer was wrong.

A scientific worldview allows both:

knowing what stars are,

feeling the wonder of looking at stars.

It only insists that we not confuse the two.

4. “Mystical” does not mean “non-natural”

This is another quiet slide.

“Mystical” in Whitman means:

emotionally resonant,

subjectively expansive,

phenomenologically rich.

It does not mean:

supernatural,

metaphysically spooky,

epistemically privileged.

A scientific worldview has no problem whatsoever with:

awe,

wonder,

altered states,

depth experiences.

It only denies that these experiences:

reveal hidden truths about cosmic purpose,

justify suffering,

or license metaphysical conclusions.

5. Where we actually differ

You are not arguing that suffering is good.

You are arguing that a world containing suffering might be justified by the virtues it makes possible.

I am arguing something narrower and firmer:

Even if suffering exists, and even if courage arises in response to it, suffering itself does not gain moral standing from that fact.

Courage is admirable.

Suffering is tragic.

The first does not sanctify the second.

And once that distinction is kept clear, the pressure to defend suffering — cosmically, theologically, or poetically — disappears.

Hope you have safe travels. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

1. Whitman is not rejecting a scientific worldview — he’s rejecting scientism.

Walt Whitman is not saying that astronomy is false, dehumanizing, or the wrong way to understand stars.

He is saying something subtler and much more important:

Charts are not the stars.

Explanations are not experiences.

Measurement is not meaning.

No defender of a scientific worldview (as I’ve described it) denies any of that.

Whitman is resisting reduction, not constraint.

A scientific worldview does not require that we:

see stars only as data,

love only in biochemical terms,

value only what can be graphed.

It requires only this:

When claims about the world conflict, the chart beats the poem about what is actually there — while the poem may still beat the chart at telling us how it feels.

Whitman leaves the lecture hall not because the astronomer is wrong, but because explanation exhausted the moment. That’s a human experiential truth — not an anti-scientific one.

2. “The map is not the territory” — agreed.

You say:

“The map is not the territory.”

Exactly.

But the mistake is thinking the scientific worldview confuses the two.

A scientific worldview says:

Maps are models.

Models are partial.

They are corrigible.

They are not substitutes for experience.

What it refuses to say is:

The map is optional.

The territory can be navigated by myth alone.

Poetry can overrule physics when consequences are real.

3. Your worldview already includes the scientific constraint.

You say:

“My worldview (like Whitman’s) includes both.”

So does mine.

The difference is not:

science vs poetry,

charts vs stars,

measurement vs wonder.

The difference is this:

You want both without hierarchy.

I want both with constraint.

That constraint is simple:

When stories, myths, or meanings justify harm, they must answer to reality.

Whitman’s poem never sanctifies suffering.

Milton’s poetry sometimes tries to.

That’s where the critique enters.

4. Courage, suffering, and the logical slip.

You define courage correctly, then draw an invalid inference.

Yes:

Courage presupposes fear, pain, or loss.

No:

Courage does not require the preservation or increase of suffering.

Courage does not require victims of genocides.

Courage does not require avoidable harm.

Courage is a response property, not a design goal.

If a disease is cured, we do not mourn the loss of bravery.

We admire those who endured it — and then move on.

If a world had:

less cruelty,

less illness,

less imposed suffering,

it would still have:

risk,

uncertainty,

vulnerability,

grief,

love.

And therefore courage.

5. “Perhaps God values courage.”

You say:

“Perhaps a benevolent God values courage, and created a world where it is possible.”

"The fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge; fools despise wisdom and instruction." - Proverbs 1:7, English Standard Version of the Bible.

As the verse shows, the Biblical God does not value courage. It wants humans to fear it.

6. The real convergence.

You are not defending suffering.

You are defending:

depth,

urgency,

vitality,

wonder,

romance.

So am I.

Where we differ is this:

You worry that reducing suffering drains the world of meaning.

I worry that romanticizing suffering drains victims of moral standing.

Whitman sides with neither myth nor measurement alone.

He sides with science plus experience.

That is exactly what a scientific worldview — properly understood — protects. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviewsThis now comes down to a disagreement over the word “worldview,” not over the substance of the position.

If by worldview you mean:

a comprehensive source of meaning, value, love, beauty, and guidance for how to live,

then I agree with you completely: science is not that, and I’ve never claimed it was.

But that concession does not do the work you want it to do.

1. A worldview does not have to supply values to constrain them.

There are (at least) two ways a worldview can function:

1. Generative – it tells you what to value, love, admire, and obey.

2. Constraining – it tells you what cannot be true, justified, or defended.

Religion aims to be generative.

A scientific worldview is primarily constraining.

And that still counts as a worldview.

Why? Because it answers fundamental questions such as:

What kinds of explanations are acceptable?

What counts as knowledge?

What sorts of claims require evidence?

What cannot be justified by tradition, authority, or narrative alone?

Those answers radically shape how one views the world — including beauty, love, and ethics — even if they don’t generate them outright.

2. Beauty and love do not float free of reality.

You ask:

“Can science tell us where to find beauty, where to find love, how to behave?”

No — and again, that’s not the claim.

But science does tell us:

what humans are,

how minds work,

how attachment forms,

how trauma damages,

how empathy develops,

how cruelty deforms,

how well-being collapses under certain conditions.

That knowledge constrains romantic, ethical, and aesthetic fantasies.

For example:

A culture may glorify domination as strength.

A myth may aestheticize suffering as noble.

A tradition may sanctify obedience as virtue.

A scientific worldview doesn’t tell you what to love — it tells you when your story about love is lying about its effects.

That matters.

3. “Comprehensive worldview” is doing illicit work here.

You keep asking whether science provides a comprehensive worldview.

But no worldview that we actually live by is comprehensive in that sense.

Religion does not tell you which medical treatment works.

Poetry does not tell you how economies function.

Philosophy does not tell you how neurons fire.

Art does not tell you whether a belief causes harm.

Every mature worldview is pluralistic.

What distinguishes a scientific worldview is not that it answers everything — but that it refuses to let answers in one domain override reality in another.

That refusal is not minor.

It is civilizationally decisive.

4. “How far Pluto is from the sun” is not a trivial aside.

You frame scientific knowledge as a minor curiosity compared to love and beauty.

But notice what hangs on scientific understanding:

whether children die of preventable diseases,

whether famines persist,

whether cruelty is justified by myth,

whether suffering is treated as sacred or solvable.

Those are not peripheral to “how to behave.”

They are central.

A worldview that treats empirical truth as optional cannot reliably guide love or ethics — no matter how beautiful its stories.

5. The real disagreement (finally stated cleanly).

So let me state the position without slogans:

A scientific worldview does not replace art, love, myth, or philosophy.

It does set non-negotiable constraints on what any of those may credibly claim.

It rejects the idea that meaning licenses falsehood.

It rejects the idea that beauty excuses harm.

It rejects the idea that tradition outranks consequence.

If that does not count as a worldview, then the word has been defined so narrowly that it excludes every serious modern outlook except religion.

You want a worldview that tells you how to live.

I want a worldview that:

does not lie about reality,

does not romanticize harm,

and does not sanctify ignorance.

Those aims are not in conflict.

But they are not the same — and confusing them is what has kept this discussion circling instead of landing.

The scientific worldview does not give us meaning.

It tells us when our meanings have crossed the line into self-deception.

And that is not a small thing; it's a significant thing. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

1. “The world is good because God created it” — that premise does all the work.

You say this is the religious worldview, not yours — fair enough. But then you continue to reason as if it were morally dispositive:

“I’m not prepared to believe the world is an evil place because people suffer.”

Neither am I.

And I have never claimed that the world is evil because suffering exists.

That is a straw target.

The claim is narrower and stronger:

Suffering is not morally justified merely because it is natural, inevitable, or narratable as meaningful.

Calling existence “good” at the cosmic level does not answer the ethical question at the human level.

A hurricane is natural.

A parasite is natural.

Bone cancer in children is natural.

“Natural” is not a moral category.

2. Mortality as tragedy and gift — agreed, with limits.

You’re right that mortality gives urgency, intensity, and romance to life. That insight is beautifully explored in "The Lord of the Rings", where J. R. R. Tolkien speaks of death as “the Gift of the One to Men.”

And Andrew Marvell captures the same urgency in “To His Coy Mistress.”

On this we agree:

Finitude can intensify meaning.

Immortality might flatten urgency.

Awareness of death shapes depth.

But notice what these examples do not show:

They do not show that suffering itself is the source of meaning.

They show that time-limitation is.

Mortality ≠ cruelty

Finitude ≠ torture

Urgency ≠ exploitation

A world with less disease, less violence, and less imposed suffering would still be:

finite,

fragile,

romantic,

urgent.

Meaning does not require victims.

3. Preventing suffering in practice — and limiting concern in principle.

You say:

“In reality I look to prevent suffering, just like you do.”

That's great. That matters more than metaphysics.

But then you add:

“Maybe I limit my concern to those sentient beings to whom I relate: dogs, cats, apes, monkeys, etc.”

That is the real philosophical fault line — not poetry, not Eden, not God.

The question is not whether compassion exists.

It is how far it extends and why.

Once we accept that:

suffering is bad for the one who suffers,

regardless of species,

regardless of our emotional familiarity,

then the circle cannot be drawn at “those I happen to relate to” without arbitrariness.

This is not about moral superiority.

It is about consistency. This is why I am a vegan. I avoid causing preventable harm to all sentient species, e.g. dogs, cats, apes, monkeys, fish, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, rats, mice, whales, sharks, octopuses, squids, crabs, cattle, pigs, lambs, goats, ducks, chickens, turkeys, prawns, turtles, birds, camels, horses, donkeys, etc.

4. “God is not evil for creating a world with suffering” — a misplaced charge.

You object to the claim that God would be evil for creating such a world.

But notice: I don’t need that claim.

As an agnostic atheist, I’m not indicting God. I am not convinced any God or Gods exist, but I am open to considering any evidence.

I’m indicting a moral move — the move that treats suffering as justified because it exists.

Even if God does not exist:

suffering still harms,

victims still matter,

prevention still counts.

Even if God did exist:

“Who can know the Mind of God?” is not a moral answer.

It is a refusal to evaluate.

Moral reasoning begins where mystery ends.

5. Natural suffering vs. moral evil — an important distinction, carefully used.

You conclude:

“It is not the suffering that is evil — it is natural. It is the ill will and lack of love that sometimes produces it that is wicked.”

This is close to the truth — but incomplete.

Yes:

Not all suffering is caused by malice.

Disease and aging are not immoral acts.

But moral responsibility enters wherever suffering is:

preventable,

amplified,

ignored,

or institutionalized.

Ill will is not the only moral failure.

Negligence, indifference, and rationalization count too.

A system can cause vast suffering without hatred — and still be morally indictable.

6. The crux — what we do with suffering, not whether it exists.

So let me put the position cleanly, without rhetoric:

Suffering and death are part of the human condition.

They can deepen love, urgency, and courage.

They are not therefore sacred.

They are not therefore justified.

And they are not therefore exempt from critique or reduction.

Facing suffering courageously is admirable.

Creating, preserving, or excusing avoidable suffering is not.

That is not nihilism.

It is not world-denial.

It is not anti-romance.

It is moral adulthood.

I am not saying:

the world is evil,

life is a mistake,

or that tragedy negates beauty.

I am saying this — and only this:

Suffering is to be reduced with compassion; it's not a feature to be increased through deliberate harm.

We can honor courage without venerating pain.

We can accept mortality without worshipping murder.

And we can love this world deeply while still working on making it kinder.

That insistence is not ingratitude. It is care. -

Comparing religious and scientific worldviews

1. Self-flagellation, chemotherapy, mountaineering — and the missing distinction.

You say:

“Nobody chooses harm unless the alternative is worse.”

Exactly.

And that sentence quietly concedes my core position.

There is a decisive moral difference between:

chosen, instrumental pain (chemotherapy, surgery, mountaineering), and

imposed, non-consensual suffering (childhood cancer, torture, slavery, factory farming).

Self-flagellating monks do not refute this. They illustrate it:

They believed self-harm prevented a worse fate (sin, damnation).

Their belief may be false, but the structure is the same: pain as means, not pain as ideal.

Now notice what never appears in your examples:

Inflicting suffering on others for their supposed good.

Sacrificing unwilling beings to preserve romance, courage, or metaphysical drama.

That absence matters.

My claim was never “pain is never chosen.”

It was:

Suffering does not become morally justified merely because it can be narrated as meaningful.

You have not challenged that.

2. Love, heartbreak, and the false implication.

You write:

“The greatest loves are the most painful… Does this mean we shouldn’t love?”

No — and this is another misfire.

Pain as a by-product of vulnerability is not pain as a moral requirement.

Love entails risk because:

we are finite,

we cannot control outcomes,

we care.

That does not imply:

heartbreak is good,

loss is sacred,

or that suffering deserves reverence.

A world with less disease, less violence, and less exploitation would still contain: