Comments

-

How LLM-based chatbots work: their minds and cognitionRegardless of how “human” large language models may appear, they remain far from genuine artificial intelligence. More precisely, LLMs represent a dead end in the pursuit of artificial consciousness. Their responses are the outcome of probabilistic computations over linguistic data rather than genuine understanding. When posed with a question, models such as ChatGPT merely predict the most probable next word, whereas a human truly comprehends the meaning of what she is saying.

-

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

Additionally, another problem with ethical naturalism is its non-deterministic nature. In any natural science, the laws or theories established are deterministic. The effects of gravity, for example, will always be measured regardless of the number of trials. However, not everyone adheres to ethics, and there’s always a significant number of people doing immoral things. The predictive power of any ethical theory is not satisfactory. I guess you could say ethics is not measured in terms of behaviors but rather by a sense of approval. But a measurement of “approval” is far from “empirical.” -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

Isn’t gravity defined as a force of attraction between masses in Newtonian physics, and the curvature of space-time in general relativity? Why is it not defined?

Naturalism and emotivism also have their own problems.

Against naturalism:

Moore’s argument takes the following form:

Let goodness be equivalent to some complex idea X (e.g. the pursuit of the desire as desired by all humans)

Then goodness = X, just as saying a triangle is a plane figure with three straight sides and three angles

This means that asking whether goodness is really X should yield no meaningful and substantial answer, just as asking whether a triangle is a plane figure with three straight sides and three angles

However, it seems that asking whether goodness is really X do yield meaningful and substantial answer (consider the case of Utilitarianism and Organ Donor Trolley Problem)

Therefore, goodness cannot be equivalent to some complex idea X

In this way, Moore refutes any attempt to define goodness in terms of anything other than itself. He concludes: “Good is a simple notion, just as yellow is a simple notion… We know what ‘yellow’ means, and can recognize it wherever it is seen, but we cannot actually define it. Similarly, we know what ‘good’ means, but we cannot define it” (Principia Ethica, §10). Therefore, any moral realist position that aims to define moral concepts in a synthetic or a posterior way render themselves susceptible to Moore’s Open Question Argument. — Showmee

Against emotivism:

One of the most well-known objections is the Frege–Geach problem. If moral statements like "stealing is wrong" are indeed senseless or not truth-apt propositions, then how is it that we can still use them in semantically appropriate contexts where they serve as components of valid logical inferences? For instance, it makes perfect semantic sense to say:

Stealing is wrong,

and Johnny is stealing,

So Johnny is doing something wrong.

We know that for a conclusion to be valid, its premises must also be truth. But if we assume that "stealing is wrong" is not even a truth-apt statement, why does the conclusion still seem logically valid in the above argument? On the other hand, if we treat moral propositions as mere expressions of emotion, it wouldn’t make for a valid argument to say something like:

Boo to stealing!

Johnny is stealing,

So Johnny is doing something wrong. — Showmee -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealismYou say "descriptive" as if saying something is descriptive somehow suggests that it doesn't relate to value. That is only true if one has already accepted that there aren't truths/facts about value. Saying facts are about "how the world is," and then expecting this to somehow make the case for anti-realism only works if you already assume anti-realism is true. — Count Timothy von Icarus

When we pursue “truth,” we typically mean aspects of the world that exist independently of the mind. By independent, I mean it is possible for their truthfulness to be perceivable from a third-person perspective apart from human consciousness. Of course, it seems implausible to access anything that is absolutely independent, but generally, the more mind-independent something is, the more “true” it seems to be. Yet values, prima facie, appear to be completely mind-dependent—especially ethics, whose existence seems to rely heavily on the presence of agency and consciousness.

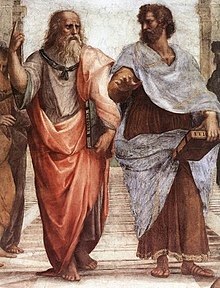

Now, I don’t think adopting a descriptive definition of fact necessarily entails moral antirealism. One could, for instance, ground normative beliefs in naturalistic explanations, such as evolutionary ethics. Alternatively, one might appeal to a Platonic Form of the Good, treating ethics as an objectively existing idea. Perhaps even if-theism (if I may call it that) could offer a foundation for ethics.

These are all forms of moral realism that could, in principle, be successful—if adequately defended. However, each faces significant challenges: naturalism confronts Moore’s Open Question Argument, Platonism must account for its obscure metaphysics and epistemology, and I haven’t yet explored moral intuitionism in depth, so I can’t speak to it with confidence. But perhaps that is your position—or at least one you sympathize with.

So, when you say that “stomping on a baby is bad,” do you mean that this is so obviously and intuitively true that it makes no sense to further analyze the sentence? And with what level of certainty are you proclaiming it, that of logic or physics? -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealismI should also add that Error Theory is only negative (destructive), yet you move away from non-cognitivism because you claim it is also only capable of negation. Can you explain why or is it just a case of having to choose one to write about over the other? — I like sushi

It is partially because I didn't had the time to thoroughly go over non-cognitivism and intuitionism. But you can see "the road to error theory" as a stream of reductio ad absurdum. Here is the roadmap:

i) we establishing realism vs anti-realism as a binary system

ii) by rejecting realism, we are left with anti-realism

iii) anti-realism includes 2 views: noncognitivism and error theory

iv) noncognitivism not well supported, so it is diched

v) So the final conclusion on ethics is any anti-realism that is not non-cognitive

vi) The only such view is error theory in this context

vii) Therefore error theory is the least refutable position (not THE position).

I guess you may disagree with iv)? -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

Just think how and why the following two statements differ:

i) Regular exercise is good for me

ii) Regular exercise helps prevent various diseases, aids in maintaining body weight, and increases serotonin levels in the brain.

To say that both sentences are true means to make the following conclusion:

C: preventing various diseases, aiding in maintaining body weight, and increasing serotonin levels in the brain are good for me

But why is this the case? Does that mean "preventing various diseases...increasing serotonin levels" is the very definition of "goodness"? If not, don't we need to keep substituting "preventing various diseases...increasing serotonin levels" with other terms until hopefully an eventual fundamental definition can be found.

This is why I don't want to right away treat these "obvious" cases as facts or true right away. I think they deserve further and prior investigation—i.e. subtitling terms—until we have a clear definition (e.g. maximum happiness is good). Then we may proceed to examine morality more carefully. -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

But I also don’t see how you get around simply assuming it isn’t bad. Why preference one assumption over the other?

It seems pretty obvious that being maimed and extreme suffering is, at least ceteris paribus, bad for animals. — “Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that when suffering occurs, our direct conscious experience is pain, which is immediately followed by a strong desire to avoid that pain. Or perhaps we could give ethics its own category of mental state. But if one identifies such desire (or ethical mental state) with the term “bad,” then the syllogism you previously provided would take the following form:

P1. I want to avoid the effects of burning (i.e., burning is not choice-worthy).

P2. If I throw myself into the fire, I shall burn.

C. Therefore, I don’t want to throw myself into the fire.

But by defining “bad” in this way, one is essentially equating moral terms with desires or emotions. That leads to non-cognitivism—a position that comes with many of its own issues.

Tracing this back to the source of the problem: you suggest there are some moral facts that can be empirically discovered, such as “x is bad.” I think it’s now a good time to ask what we mean by a fact. Perhaps this is the real point of contention—maybe we don’t share the same understanding of the term. For me, a fact is an aspect of the world, and statements that reflect facts must be descriptive in nature. The key word here is descriptive—that is, concerned with how the world is. So if we are to give morality the status of facthood, then a clear metaphysical and epistemological account must be provided.

To be clear, I don’t want to reduce all facts to physicalism—that seems a bit reckless. After all, the ontology of conscious states seems different from that of biochemical processes. But when you mention medicine, veterinary science, zoology, psychology, etc., these are all disciplines that deal with the physical aspects of the world. These empirical sciences do not lose their predictive power—their “dealing-with-facthood”—if one rejects ethics or value as you mentioned.

Even if I deny that “taking vitamin B is good for me” is a moral fact, vitamin B doesn’t stop helping to form red blood cells. Note how the latter part about vitamin B is solely descriptive. This points back to the original question posed by my essay: how do we define morality and moral terms, and what properties do they have (i.e. real or unreal)? This is the most fundamental question—one that must be addressed before we can meaningfully interpret, evaluate, or debate any moral propositions.Lastly, you might consider that being committed to such a rejection of values means rejecting a great deal of medicine, psychology, economics, etc. as not actually dealing with facts. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Prima facie, "gratuitous suffering is bad for us" seems as obvious as, "water is wet," and your response is akin to: "you cannot just assume that water is wet." — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is interesting. I think my starting point for anything is logic, and I assume that nothing exists until it is proven. Are you taking a phenomenological stance, beginning instead with consciousness?

For me, "water is wet" is a perception of mind (what Locke calls a secondary quality). While the existence of such mental state may be a factual statement (i.e. "the feeling that water is wet exists as an idea in my mind"), the content is not necessarily so (i.e. "wetness is a real property of water"). Perhaps similarly in ethics, when we proclaim "x is bad", badness is not an inherent aspect of the world. But all these, again, follow from my understanding of the term "fact," maybe it helps to put out your view on this.

So even if you have good arguments here, it cannot possibly be "better" for me to agree with you here, right? One should only agree with you if they just so happen to prefer to agree with you. Otherwise, there is no reason to prefer truth over falsity. It's an arbitrary preference. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think the distinction between two dualisms must be made clear here: objectivity vs. subjectivity, and mind-dependent vs. mind-independent. Things can be mind-dependent without being subjective. Instincts, for example, are mind-dependent, but they are also shared among all humans. So the preference for truth over falsity is not merely an arbitrary choice, but an objective tendency rooted in our shared cognitive nature. It may be arbitrary in a metaphysical sense—there is no necessity that the universe values truth—but this is not the case in a social or cultural sense, where the preference for truth is stable, widespread, and normatively reinforced. -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

because analytic philosophy doesn't talk about ethics, epistemology and ontology at the basic level, the level that belong exclusively to philosophy. — Astrophel

Could you elaborate on the "basic level" you are referring to, I am really curious about it.

Moral principles that are universal?? — Astrophel

I think this is a misunderstanding. From previous conversations with Tom, I used the word "universal" not to mean necessary in a logical sense, but to indicate that it is objective, namely something that is shared by all humans.

but at the core of every system lie certain objective moral principles that are universal to all humans (e.g., that one should not kill an innocent person merely for personal pleasure). — Showmee

ethics as such transcends reduction to what can be said about ethics. Rorty's failing lies in his commitment to propositional truth, that is, truth is what sentences have, not the world. But this truth is derivative OF the world, and thus, the world has to be understood inits ethical dimension, not in the finitude of language. — Astrophel

I’m not sure if you’re adopting the stance of the early Wittgenstein, but one thing I don’t understand is whether he’s smuggling in a kind of metaphysical realism about subjects that transcend language and logic. When he says ethics is “nonsensical”—which, by his picture theory, means it cannot be represented within the space of possible states of affairs—what is he really trying to show? Do they exist or not exist or cannot be known? -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

It is bad for children to have lead dumped into their school lunches.

It is bad for people to be kidnapped, tortured, and enslaved.

It is bad for a fox to have its leg mangled in a trap.

It is bad for citizens of a country to experience a large-scale economic depression.

[...]

It seems fairly obvious that the truth of such statements is something that we can discover through the empirical sciences, the senses, etc. To insist otherwise is to insist that medicine, veterinary science, biology, welfare economics, etc. never provide us with information about what is truly good or bad for humans or other living things. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think it is unfair to claim that these cases are facts that can be discovered through empirical sciences. While they strike us as merely descriptive propositions, there are implicit value prescriptions in the presumption of each case. For example, let us take the case that 'it is bad for the fox to have its leg mangled in a trap.' The truly descriptive proposition is 'having its leg mangled in a trap decreases the fox's probability of survival.' To say that this is 'bad' for the fox presumes that survival is something worth pursuing. The same presumption about the value of survival is present in the case of 'it is bad for people to be kidnapped, tortured and enslaved,' because these conditions increase the likelihood of death. So if one is to claim these as facts, then one must first accept certain presumed values, such as that survival is worth pursuing. Therefore, to merely use the words "good" or "bad" is to presume that they are meaningful terms and that they refer to some definition. Even in philosophical discussions, when we say an argument is "bad", what we really want to say is that this argument does not meet the criteria of logical coherence, which is already something we think worth pursuing (I will expand a bit on this later).

Further, it certainly seems that empirical sciences such as medicine, vetinary science, etc. can at least sometimes tell us about what is truly choice-worthy. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't think you can just assume that there are things that are choice-worthy, and by observing that empirical sciences can be used as a tool to direct us towards these "things," conclude that empirical sciences discover moral facts. I'm not saying that these choice-worthy things are purely subjective. Take survival, for instance: it is something deemed worth pursuing by all humans, if not all animals. But just because we have the intuition and desire to survive does not mean "one must pursue survival" is a fact.

So I think the reasoning:

P1. The effects of burning are bad for me (i.e. burning is not choice-worthy).

P2. If I throw myself into the fire, I shall burn.

C. I ought not choose to throw myself into the fire. — Count Timothy von Icarus

is not valid on the ground that P1 is not true (at least without first examining the implicit value prescription i.e. avoid pain is good), and thus cannot be used to construct a valid argument.

Just consider what it would mean to deny values if we weren't separating off a sort of discrete "moral value." If practical reasoning (about good and bad) is not distinct from moral reasoning (about good and evil) and we deny practical reason, then we are denying that truth can ever be truly "better" than falsity, that good faith argument is better than bad faith argument, that invalid argument and obfuscation of this is ever worse than clear, valid argument, etc. Having taken away all values, argument, the search for truth, etc. seems to boil down to "whatever gets me whatever it happens to be that I currently desire." — Count Timothy von Icarus

I see no problem with saying that the entirety of philosophy is based on the assumption that truth is worth pursuing (if I had to). The fact that the pursuit of truth is a subjective desire has no bearing on the validity of a person’s arguments. Ultimately, pursuing truth could just be simply an activity people choose to engage in, regardless of its deeper meaning. I take the same view with respect to morality: if morality is something inherent to human nature, then I will practice it (which I do, just fyi). But that does not automatically make morality a fact, and to claim that it is already presupposes that truth is worth pursuing. Therefore, I believe one can practice morality without regarding it as objective truth, just as one can practice philosophy without viewing it as objectively superior. -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

I would say that a value is a prescriptive idea that makes its possessor believe everyone else ought to approve of and adopt it.

Values usually represent a transition from facts to rights, from what is desired to what is desirable. — Albert Camus -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealismBut you’ll note, over a century ago a woman with a job, for instance, was considered deviant and wrong. This was a feeling also. Today (unless you’re in some unsophisticated or uber religious part of the world), the idea of women with jobs is not seen as a moral problem. — Tom Storm

The premise of gender equality is that all humans must be treated equally. From there, it is easy to construct the argument for feminism:

All humans must be treated equally.

Women are humans.

Therefore, women ought to be treated equally.

The problem with ancient or traditional moral systems is that our ancestors did not recognize the second premise as true. In essence, they regarded women as “sub-human.” As a character played by Jack Nicholson once quipped, when asked how he writes women: “I think of a man, and I take away reason and accountability.”

I lay all this out to highlight that the first premise is more fundamental—an invariant moral principle that transcends both historical periods and cultural boundaries. It is precisely these kinds of foundational moral statements that I find most compelling.

different cultures develop distinct moral systems, but at the core of every system lie certain objective moral principles that are universal to all humans — Showmee

So yes, one can imagine a society where women are treated as inferior and everyone believes this to be just (such societies have indeed existed). But to reject the fundamental proposition that all humans must be treated equally—while simultaneously acknowledging that minorities are fully human—seems less conceivable. -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealismAll i think taking a non-cognitive approach to morality does is dispel the need to explore failing theories. — AmadeusD

The [non-cornitivist] arguments themselves are constructive, and obviously account for things like moral disagreement better than cognitivism. — AmadeusD

I think there are actually plenty of problems that challenge the soundness of non-cognitivism. One of the most well-known objections is the Frege–Geach problem. If moral statements like "stealing is wrong" are indeed senseless or not truth-apt propositions, then how is it that we can still use them in semantically appropriate contexts where they serve as components of valid logical inferences? For instance, it makes perfect semantic sense to say:

Stealing is wrong,

and Johnny is stealing,

So Johnny is doing something wrong.

We know that for a conclusion to be valid, its premises must also be truth. But if we assume that "stealing is wrong" is not even a truth-apt statement, why does the conclusion still seem logically valid in the above argument? On the other hand, if we treat moral propositions as mere expressions of emotion, it wouldn’t make for a valid argument to say something like:

Boo to stealing!

Johnny is stealing,

So Johnny is doing something wrong.

Here is a nice quote from the book Ethical Intutionism to further elaborate the problem:

Thus, suppose the non-cognitivist says “There’s a right way to handle this situation” means “There’s a way to handle this situation that I would approve of.” Now ask: Does “x is right,” by itself, mean “I would approve of x”?

If the non-cognitivist says “yes,” then he has abandoned non-cognitivism in favor of subjectivism. “I would approve of x” is a factual claim, which is either true or false, not a non-cognitive utterance.

If the non-cognitivist says “no,” then he must say that “right” shifts its meaning between the following two sentences:

There is a right way to handle this situation.

The right way to handle this situation is to draw straws to decide who gets on the lifeboats.

In the first sentence, “right way” means “way that I would approve of,” but in the second sentence it supposedly functions to express a non-cognitive emotional attitude toward drawing straws. If so, then the second statement does not entail the first. But that’s false: “right” obviously has the same meaning in both sentences, and the latter sentence obviously entails the first. — Micheal Huemer -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealismI think this has been—and perhaps still is—my intuitive stance: that different cultures develop distinct moral systems, but at the core of every system lie certain objective moral principles that are universal to all humans (e.g., that one should not kill an innocent person merely for personal pleasure). These fundamental moral principles are what philosophers are primarily interested in. They ask questions such as: Where do these principles come from? What is their metaphysical status? And how do we come to know them? The answers to these questions form the basis for the main metaethical positions mentioned in my essay: naturalism, intuitionism, non-cognitivism, and error theory. (There’s also subjectivism, but I don’t yet fully understand it.)

Now, if I’ve learned one thing from philosophy, it’s to restrain myself from making belief-changing judgments before thoroughly exploring all the available information. While I, too, intuitively feel that moral propositions are artificially constructed and mind-dependent, it's still an interesting question to ask whether it might be the case that these principles possess the same degree of self-evidence and absolute certainty as logical or mathematical statements.

I mean, is it really possible to imagine a world where people kill whenever they feel like it—and genuinely regard this as morally acceptable? Or is the concept of justice truly contingent, when it just feels inherently wrong for one of two equally qualified candidates to be chosen solely because she is a good friend of the selector? -

Moral-realism vs Moral-antirealism

“Meta” is a prefix derived from the ancient Greek word μετά, which literally means “after.” In philosophical and broader academic contexts, however, it typically signifies an approach to a subject that emphasizes on reflection, transcendence, or taking a broader and often more abstract perspective. I mean you can understand it by taking a look at how it is used in the following examples: metanalysis, metaphysics, metalogic etc.

So in this case specifically, ethics is the field concerning the normative nature of ethical propositions, whereas metaethics sort of "takes a step back" and asks more fundamental and essential questions pertaining to the ontology and epistemology of ethics. -

What are the philosophical perspectives on depression?

What is the definition of "meaning" for you? When I use it in the context of "the meaning of suffering" or "the meaninglessness of the universe", I am referring to a conscious-independent purpose or value.

So when you say this, are you affirming that there is a mind-independent purpose or design that underline those atrocities?it would be selfish to act pretending that human misery is meaninglessness — javi2541997

From my perspective, things just happen. If one truly wants to make an objective assertion, then it must be descriptive in nature, not prescriptive or teleological. Of course, it is perfectly human to attach emotions to the things we see and hear, but to ask what the "fundamental" meaning of these things is in the aforementioned sense, I suppose, is meaningless (in a semantic sense). Asking why children suffer from war is the same as asking, say, why it is raining or not raining right now—if by "why" you are not referring to a physical or psychological process or causation, but rather to a metaphysical purpose.

Wishing the death of a father (The Brothers Karamazov) or stealing your daughter's money because you are a gambler. People do this, and after that, the following can happen: regretting or not caring. I go for the first option, and I explain to you why: for unknown reasons, people tend to act viciously, and when they understand the moral consequences of their acts, it is too late. Now that the problem has happened, what can we do? If I wasn't ethical in the first place, why am I suffering from my consequences now? — javi2541997

So here, I would say the first question—"Now that the problem has happened, what can we do?"—is a sensical one, as it seeks a response within the same dimension of the issue, namely, practicality. However, the second question—"If I wasn’t ethical in the first place, why am I suffering from the consequences now?"—can only be answered if one accepts the existence of "meaning" in a metaphysical sense. Moreover, the answer would vary depending on one’s metaphysical stance. -

What are the philosophical perspectives on depression?

I think it would be helpful to first identify what exactly the problem is—in this case, determining which specific type of depression you may be experiencing. According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), depression is not a single, uniform condition but rather a group of related disorders that fall under the category of “Depressive Disorders,” each with its own diagnostic criteria, features, and clinical course. Given the condition you described, perhaps (with apologies, and please feel free to correct me if I’m wrong) two specific disorders might be relevant: Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia). They differ in terms of severity and duration. Severity can be formally assessed using the following criteria:

- Depressed mood daily

- Loss of interest in almost all activities daily (anhedonia)

- Significant loss/gain of weight (Δ of 5% in a month), or decreased/increased appetite

- Insomnia/hypersomnia daily

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation almost daily

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feeling of worthless, inappropriate and low self-esteem

- lack of concentration and indecisiveness

- Diminished cognitive abilities

- Recurrent thought of death or suicide

For MDD, the first two symptoms must be satisfied, followed at least by three additional symptoms from the list, lasting at least for two weeks.

Dysthymia is the presence of two or more of the symptoms and characterized by a depressed mood for at least 2 years (1 year for children or adolescents).

The next step, then, is to identify the contributing factors, which I believe is your main interest here. From a psychiatric perspective, all factors can be classified into the following five categories:

- Genetic

- Neurobiological

- Social/Environment

- Personality traits

- Cognitive

Genetic factors include a family history of depression, with heritability estimated at approximately 30–40%.

There's no need to elaborate on the neurobiological aspects here, as they mostly concern biological mechanisms.

Social and environmental factors encompass the influence of one’s surroundings, such as adverse childhood experiences, chronic stress (e.g., from work), and low socioeconomic status. Personal history—such as a specific traumatic or tragic event—also plays a role.

Personality traits, particularly high neuroticism (a dimension of the Big Five model), are associated with a higher risk of depression.

Cognitive factors generally involve maladaptive thinking patterns that consistently interpret life experiences through a negative lens.

Each of these categories corresponds to potential healing strategies. For example, if depression arises from social factors, then expanding one's social network can be highly beneficial. In my view, these categories are deeply interconnected, so the most effective approach is to address all of them—perhaps with the exception of genetic factors, which are largely beyond one’s control.

Given your interest in the philosophical perspective on depression, particularly through existentialist novels and doctrines, this can be seen as an exploration of the cognitive aspect. If one adopts the view that human existence is inherently marked by suffering and internalizes this belief, then the onset of depression seems almost inevitable. While there may be a grain of truth in Dostoevsky’s recurring themes of human misery, I think it is misguided to focus exclusively on this aspect. One could just as easily find numerous counterexamples. What often appears to be timeless human suffering is, in many cases, the result of specific historical and political conditions.

While I stick the TV on, and I watch a lot of children dying in Gaza or starving in a random village in Africa. — javi2541997

You also mentioned the topic of fairness—such as the plight of children affected by recent global conflicts. But contrary to popular belief, I would argue that nihilism offers a better cognitive framework than sheer pessimism, both in terms of psychological effects and logical coherence. In fact, nihilism serves as the starting point for many existentialist thinkers. Sartre, for instance, saw the inherent meaninglessness of the world as the foundation for human freedom and agency. Camus, on the other hand, insisted that the beauty and essence of life lie in the absurd revolt—our rational craving for meaning set against the irrational silence of the universe.

destiny and circumstances are often the things that make me feel depressed. I always wonder, "Why does this happen to me?" Or "Why did I make this decision?" etc. — javi2541997

So, questions of this sort are resolved by deeming them senseless. I mean, it's essentially an attempt to find an objective (in the sense of mind-independent) answer to a subjective (mind-dependent) question.

Of course a common response to the premise of nihilism is "why don't you just kill yourself". So it is worth noting that nihilism is the mere assertion of a lack of inherent value in a mind independent universe. One still could affirm or exercise personal beliefs, whether they stem from cognitive (i.e. intellectual pursue) or biological (i.e. happiness) grounds.

In any case, I wish you strength and improvement in your journey. -

Ongoing Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus reading group.Hello guys, new to this discussion. I don't know if you have already discussed this but I am having a hard time to understand what a symbol is. All I know is that it is the same thing as an expression, which is what characterizes a proposition's sense (3.31). So for example "x is y" taken altogether is an expression, I guess. But when Wittgenstein starts to discuss the relationship between signs and symbols, he says that , for example, "is" is a sign for the symbol of copula. But "is" itself does not characterize any sense in a proposition such as "x is y". I tend to identify symbols with names, and a sign is just a physical expression of a name, but names have no meaning without being a part of a proposition.

Also, since I brought up names, can anyone tell me what a simple word, such as "cat" is? Is it an atomic fact or a name, because on the one hand its definition seems to consist of other signs thus is not a primitive sign, and on the other hand "cat" alone doesn't seem to mean anything.

Thanks a lot. -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

I think for me, the problem with idealism is its extremely anthropocentric nature. It seems that this position supports the claim that the material world would cease to exist had human consciousness ended. If so, don't you think that we might have endowed to ourselves too much significance? Moreover, along with idealism follows the universal scepticism, which leads only to solipsism. Also, how do we define consciousness if we are to claim that the world is a mind-dependent entity. Does it depend on individual consciousness (without me, the world may cease to be) or on the collective consciousness of humanity (without humans, the world may cease to be). -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

So in short, your view is that we are to be content with dwelling within the subjective interpretation we as a species formulated, whilst simultaneously recognizing that the true/objective nature of the world is incomprehensible by not claiming neither the world has a meaning nor it’s devoid of meaning?

Sure, but everything humans do is natural by definition. From mass murder to painting pictures of Krishna. — Tom Storm

This actually is a quite ambiguous theme that I need further insights on. We often automatically draw a line between our own existence and Nature. However, it is also true that our consciousness, that is what enables us to produce our subjective reality, is begotten by nature through evolution. Maybe the distinction between objectivity and subjectivity arises only from the first person perspective we stand upon? Because if we imagine ourselves as beings external from this World, humans would seem to us as an integral part of this universe, encompassed within Nature. Thus, the entire cosmos would be analogical to our body, where the role of humans would be similar to that of the brain, carefully perceiving and examining the rest of the body, which are unconscious on their own. In other words, the concepts of subjectivity and objectivity converge into a unity, and thus the world does possess an intrinsic meaning in that we as meaning-making beings are a part of that world. On the other hand, does there exist a possibility such that consciousness has its own existence outside of nature, albeit the former has its root in the latter? Think about ChatGPT: it is an AI technology invented by humans. But if I command it to write a poem (which is similar to the mass murder example you gave), to what extend am I eligible to claim that this poem is mine.

Note that these concepts are not consolidated within my system of knowledge, thus further critiques are required. Thank you. -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

All we have is life, this is our reality. I don't think humans ever arrive at or know some external to self 'reality'. As you say, humans inhabit a world of their own making, a function of our experience, our cognitive apparatus and shared subjectivity. Do we need more than this? — Tom Storm

I guess you could say that it is precisely the humanity's inability to comprehend reality which makes it devoid of meaning (though I think reality is just the way the world is as it is, without any meaningful properties). However, I would regard seeking an objective meaning as a natural impulse. We as rational animals constantly ask ourselves, "who are we", "where did we come from" and "where are we going". And it is genuinely difficult for a person to fully renounce a sense of metaphysical egocentrism. -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

Terms like "exists," "is good," "is necessary," etc., when applied to God, are necessarily all forms of analogical predication, as opposed to the standard uniquivocal predication at work when we point to a real tree and say "this tree exists," or "this tree is green." We know of God's "goodness," or "necessity," through finite creatures' participation in an analogically similar, but lower instantiation of the property. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think the analogical view here does not necessarily stand. Sure, when we say "the sun is bright" and "this colour is bright", the predicate "bright" is not univocal; but terms you provided such as "exist/being", "good", and "necessary" transcend the boundaries of the ontological categories (say that of Aristotle), applying across all of them. As Duns Scotus insisted, a concept is univocal when:

"it possesses sufficient unity in itself so that to affirm and deny it of one and the same thing would be a contradiction. It also has sufficient unity to serve as the middle term of a syllogism, so that whenever two extremes are united by a middle term that is one in this way, we may conclude to the union of the two extremes among themselves. (Ord. 3. 18)"

For example, "being good" could be defined as a subject manifesting highly its quiddity or telos. Thus, a "good" man is a fully rational man; a "good" knife is a very sharp knife; and a "good" God is a God that is omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent (assuming these are God's essence). The predicate "being" is univocal in a more apparent way. When X is, X exists in reality. How can "being" thus be analogical, unless you say that the existence of God in reality is different from the existence of anything else by being either more or less real (what does "more" real even mean)? It's both unclear and unnecessary. -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

I mean, that's certainly a popular dogma, but I don't think it's by any means something that has been well demonstrated. Plenty of thinkers have thought they have discovered something quite the opposite, reason and purpose at work throughout the world. The "rock solid" foundations for the claim that the universe is essentially "meaningless and purposeless," seem to be to be grounded by the same epistemic methods that tend to ground religious beliefs — Count Timothy von Icarus

That is a very valid point worth reflecting. However, religions and other beliefs, in terms of logic, are deductive conclusions (e.g. the Ontological Argument presumes the existence of God) without any valid empirical evidence to support their propositions (many times these systems even lack logical validity). On the other hand, nihilism is an inductive conclusion, derived from the observation that so far no belief or religion can adequately prove the existence of an objective meaning independent of the mind. Nihilism is not a simple affirmation, it is a negation of other affirmations. This is the very reason I included also a weaker version of nihilism, claiming that "even if there exists a meaning or something sublime and superior such that a definition or a providence is indeed bestowed to the universe, it is, nonetheless, most certainly hidden away from the domain of pure reason."

Thus, demanding a religious person to prove the existence of God is not the same with demanding, say, an atheist to prove that God does not exist. It's like demanding a physicist to prove that a fifth fundamental force does not exist. In fact, if we observe the history of physics, we find that scientists always faithfully followed the so called Occam's razor:" entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity." Whilst I understand that physicists are able to utilize empirical measures to obtain their results, both physics and nihilism share the same notion that if X is not a logical necessity and cannot be proved empirically, then X can be eliminated from the system of knowledge. Therefore, if an objective meaning or purpose is not a hard necessity for the existence of us and of the world, and such meaning cannot be proved empirically, it follows that this world does not require any intrinsic meaning.

Fundementally irrational how? The world seems to operate in law-like ways that can be described rationally quite well. Indeed, this is often a key empirical fact cited as evidence for universal rationality or even purpose (e.g. the concept of Logos Spermatikos). — Count Timothy von Icarus

The fact that this world functions in a seemingly law-like manner does not necessitate a creator or an intrinsic meaning, since the universe may exist in other unimaginable forms had it started slightly different. It's all merely probabilities. Furthermore, the predicate "law-like" we apply onto the function of the universe is a concept begotten by rationality; it's a conclusion yielded only by beings capable of recognizing patterns, which are merely different arrangements and configurations of information. For me, all things, objectively speaking, merely exist. Any other description one might add is just a subjective interpretation of the world. One might argue that even without our existence, this universe would function in the exact same law-like manner; but in reality, it would merely continue to function, and not in a "law-like", "chaotic", "beautiful" or any other way.

I also don't know how this would make the universe somehow lack quiddity. It still is what it is. Is this a claim about our epistemic ability to understand the essence of the universe, or a claim about a lack of essence simpliciter? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Quiddity is merely a nominalistic existence, a product of cognitive abilities. The essence of a rock for humans may be its hardness, but if we were stronger, say being able to smash rocks easily, its essence would consequently change too.

But the idea that religion is some sort of "cope," a flight from the terror of the "meaninglessness and purposelessness," of the universe seems to be somewhat an existentialist dogma. Why would this be the case for people who simply don't believe the existentialist claim the the meaninglessness of existence? If they have never believed that claim, then they will have had no motivation to generate such illusions in the first place. It seems to assume something like: "deep down, everyone knows our claim is true." However, I don't think this is the case at all, and empirically it seems hard to support in light of phenomena like suicide bombers. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Whilst I agree that the origin of religion is better explained by other more scientific theories, it is an undeniable fact that one of the main reason a substantial proportion of the contemporary population still finds refuge in religion is to cope against the fear of death, either consciously or unconsciously. As for the suicide bombers, or even self-immolators, they are those who had already conquered the fear of death through having faith in the continuity of their spirit posterior to death. And it's an excellent example of how people are often misguided by their own creations—religion in this case, as I had pointed out in my essay.

Second, isn't science as good of a candidate of an objective description of the world as we have. But if scientific explanations are rational, often framed in mathematical terms, then why would we say objective reality is "irrational?" It seems to submit to rational explanations quite readily.

Objectivity only makes sense in the context of subjectivity in any case. It's the view of things with relevant biases removed. The claim then would be that removing all biases would also remove all rationality? But why should we accept that? — Count Timothy von Icarus

The universe is irrational in the sense that there exists no meaning. I don't see how the rational discoveries/descriptions of science has any connection with an intrinsic meaning. -

The Conjunction of Nihilism and Humanism

Thus God is irrational? — tim wood

Only when God actually exists. And even then, yes, I would regard Him irrational in the sense that His essence is beyond the realm of human understanding, and thus "irrational" here does not bear any diminishing implications, but signifies only the incapability of rationality to grasp God.

What do you mean? Don't we have, in various forms, "nothing is without reason." Does not the world and the universe appear soon enough to yield to reason where reason chooses to look? — tim wood

It depends on the exact definition of "reason". If by "reason" you refer to causality, then sure, but that is irrelevant to my propositions. However, if "reason" signifies providence and intention, e.g. God created humans to love Him, then no, I don't think anything has a "reason".

English words: but what do they mean? What are you trying to say? — tim wood

Human intellect is unable to grasp the meaning the world, because either the world has no meaning to start with, or the cosmos is described by something intangible through rationality.

Facts and values entirely unrelated? That seems extravagant. And so forth. I suggest, fwiw, you ask yourself what you are trying to say, and try to say it in four or six or seven well-crafted sentences, if even it takes that many. Else people like me (and the others of TPF) will be asking you for clarity, definitions, and meaning, and if you're lucky, explicitly. — tim wood

Facts are members of the objective world, and values are our subjective interpretation of facts we perceive. I would say that the relation between these two concepts is not bidirectional. Namely, values judgements depend on facts, but not the other way around. And since in this part of the essay the focus is on the factual aspect of the world, "[...]this categorisation is entirely unrelated to value judgments but only to factual properties."

+ You mean I write overly complex sentences which are ambiguous?

And this all encompassed and included in the opening words of the Creed, "We believe." And once you're clear on that, you can believe what you like, and what follows much like a game, of course with rules. Is it a game you wish to play? — tim wood

Could you please elaborate on your question, I don't quite get it, sorry...

Showmee

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum