Comments

-

The Christian narrativeA better approach might well be to accept that the Trinity is a mystery, and not to look for coherence. If that's your point, I'll agree. — Banno

Well, I agree it is impossible to simply grasp the Trinity, especially when trying to do so in a math class or a logic class.

But when two Christians are faced with what they believe Jesus said and meant when he said he and his father are one, they can make reasonable statements about it, to try to grapple with it and understand it more, and correct error about it and discover new facts. Just like two mathematicians grappling with the set of all sets. It’s incoherent, but still it is there to grapple with, to perplex, to face head on anyway.

In other words, yes it’s a mystery, but that doesn’t have to nothing more can be said. That doesn’t mean nothing can be said as true about the Trinity and no one can say other things are false about it. Ground can be covered while the mystery remains. -

The Christian narrativetrinity is a mystery, then leave it as such — Banno

I think you can still reason about mysteries.

Like Frege and Russell did. “How the hell do sets collapse into impossibility?” -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingDo you think we can discover something new by changing the perspective in this way? — Astorre

I think we might discover a way to understand something (namely, being/becoming), that does not linguistically look rational.

Meaning, the way we normally talk follows a reasoning.

But there is no normal way to talk about “being” qua being. When we talk normally, and make our topic “being”, we impose things in the topic that obfuscate and cover up what we are trying to say.

When talking about being/becoming, it is often the case that with each word we use, we turn our attention away from being/becoming.

Like you said the question “What is being?” doesn’t even make sense in Russian. I think what we are discovering is that, while “being qua being” is mysterious, and therefore, worthy of inquiry and discussion, even if we discover some wisdom about it, it will be difficult to say or demonstrate with reasonable statements.

So short answer to your question is, yes, I do think a new perspective, or really a new eyeball, (a new logic), needs to be developed to philosophically (not metaphorically or mystically) talk about being/becoming. And your observation about what is present in some languages but not in others relating to something so basic as “is” are really good because they point to a newer method (way of looking - through linguistic analysis), and a bit of new wisdom as a result (being as a piece of Becoming, so to speak). -

The Christian narrative

I think people who find themselves in opposition about God questions might actually show a bit more support for each other’s perspectives.

Set Theory is like a neutral ground to understand seeking to logically penetrate a mystery that seems impenetrable.

Sets obviously function.

But then there is the Set of all Sets - impossible and defies all logic (yet it keeps rearing its head and underpinning logical progress..)

This is a type of mystery in the face of clear evidence/logic. We sort of have to live with how simple sets clearly are useful, AND how sets are ultimately impossible. We can call this where logic meets mystery.

So we can give the believers in the mysterious Trinity a pass (letting them have their evidence AND letting them attempt to logically explain and make coherent something that seems must be a paradox and to yield contradictory statements).

I’m just saying, the emergence of mystery is not fatal and need not end the reasonable discussion. -

Alien Pranksters

The question is this: given enough time and computing power, can humanity eventually "discover" an interpretation that renders the text coherent? While in truth, inventing one out of whole cloth? — hypericin

That’s two totally different questions

1. Can we see the meaning in the text?

2. Would we fool ourselves that a reasoning we imposed on the text was in the text when it was not?

My answer to both is no, probably not (“definitely not for me, but Incant speak for everyone.)

Seems reasonable to assume it is language and text. But maybe it isn’t. But still seems reasonable to assume it was made by something sentient, like us, but maybe not. Until we find a Rosetta Stone, or a decryption key, confirming it is indeed a language at all, or even an artifact of a knowing being, I think most people would never get too far convincing others about the “meaning” of its “language.”

Did you see the movie “Contact” with Jodi Foster? They had a similar alien text problem. The aliens built in a decryption key to help other intelligent species learn the language. Neat movie. -

The Christian narrativeThere are numbers all over the place — frank

Like in order to have a single open and honest discussion, we have to first have half of such a discussion, and before that, half of that half…until we realize this goes on infinitely and a single open and honest discussion was impossible from the start. Too many numbers… -

The End of WokeThe only way that unconscious entities can be brought to bear within a deliberative philosophy forum is by first bringing them into consciousness. -Leontiskos — Joshs

Yes.

For any ideas which are important to us, it is a mistake to say they are unconscious or that we are unaware of them. The challenge we often deal with is in articulating why and how they are important to us. — Joshs

Leon’s unconscious entities are neutral and just need to be brought to the fore. Leon is pointing to “what”.

Joshs unconscious entities are the “why and how” of importance.

Still yes.

how long we last until we start talking past one another. — Joshs

I admit my writing style is not the best, I go too fast, fail to edit, but I truly try to be open and honest and clear and respectful, and even grateful, and in-debted when I read some of the things you guys make so clear. My apologies. I can be a wise ass and even know I sound dismissive but I am truly not dismissive and would rather just know we all already can get along as people, like cousins, so we could hash out a good, blood soaked argument, never talking past anyone.

Calling each other out for saying something stupid is one thing. That doesn’t mean you aren’t also brilliant. At least that’s how I do it. (See, I just used a double-negative because that is how I would say it “doesn’t mean you aren’t”. Sorry! Internet is a blessing and a fickle bitch.)

“wokeness” concerns all of us. — Number2018

Yes.

the challenge with wokeness lies in its resistance to precise definition or straightforward philosophical inquiry. — Number2018

Wokeness is a reflection of the fact that precise definition and straight inquiry are challenging to come by. Wokeness embraces the challenge leaving the end, the overcoming and completion of the challenge, unfinished, without “precise definition” or “straight” lines of inquiry.

Yes.

Its meaning shifts depending on political perspective, social context, and rhetorical intent. — Number2018

You could have stopped here to fix the point this makes to me: “It’s meaning shifts.”

So nothing you just said about where its meaning shifts (perspective,etc) is wrong at all. But I pause at simply the notion “woke’s meaning is a shifting thing, unfixed.” That, I think, is a perfectly neutral observation about “wokeism” - we are going to have leave some lines undefined and unclear if we are to clearly see “what is woke.” That’s what woke is - it resists to stagnant form embracing change qua change; but that is always woke. So when we draw the line and point clearly “that is woke - like trans rights are woke” - we are also pointing not to any clear lines but maybe to areas or frameworks or local systems of agreement…

Likely, what makes wokeness so urgent is its implicit relation to power. — Number2018

Yes, It is urgent. It is immediate, and self-evident at times, like injustice. This involved is real power that must be managed, and judged, and in support of calls to action, a morality.

Its influence is subtle, diffuse, and often operates below the level of conscious awareness. — Number2018

This speaks to how it is undefined again. What is unconscious is the same qua unconscious for the woke and the anti-woke (qua unconscious). But this unconscious for the woke is a comfort level with ambiguity and undefined things. So it’s influence may be subtle but that is not intrinsic to wokeness - its influence could be dramatic and loud.

The term unconscious is often overused and should not be understood here in a purely psychological sense. Rather, it refers to a regime that operates across heterogeneous domains and builds a cumulative strategic resonance. — Number2018

Yes, that is part of the “how” Joshs was relating/contrasting with Deluze and the other writers.

[this produces] specific expressions — Number2018

Yes - there is a particular character, nevertheless, to the woke. (Like with anything, there is its particular character and how this blends in with its context…)

not as such due to objective empirical evidence, but because of how they resonate within affective and social contexts. — Number2018

Yes. The character of wokeness involves its context more than its own defined “in-itself” and this “affective and social” context IS where woke finds it clearest definition in its struggling self.

There is a lot more to say.. -

The End of WokeWe now seem to be discussing how to discuss “How to develop methods of discussion” with a sub-topic “methods of discussing wokeness” (and a hope that we will eventually discuss wokeness itself).

-

I've been trying to improve my understanding of Relativity, this guy's videos have been helpingRelativity tells us spacetime can be stretched, — flannel jesus

Ok - so invisible gravity has been replaced by space which stretch and compressed etc can be measured. Like things can be measured. Ok, I sit corrected. :up: -

I've been trying to improve my understanding of Relativity, this guy's videos have been helpingThe arena — flannel jesus

But “arena” has to be analogy - it’s not an actual arena. It’s not like “space” can be a “thing-in-itself” like an arena is a thing.

So I’m not trying to argue against Einstein, or Newton, or you. I’m just saying it is all still, in my mind, “full of holes” (if holes can be used to fill something). -

The End of Woke

but without judging the value of the things being stretched, just to judge the length of the stretch — Fire Ologist

You forgot:

5. Pretty white girl who talks about her genes.

6. Someone who is having a seizure because they saw the ad. -

I've been trying to improve my understanding of Relativity, this guy's videos have been helpingTotally interesting video and great teacher. Will watch more videos.

So now that gravity isn’t a force, what the hell is space- time (with a curvature to it)?

We go from abracadabra to hocus-pocus.

Job security for people way smarter than me. -

The End of WokeIt seems like a stretch to compare longboard surfing, something that doesn’t even qualify for the Olympics, to child abuse, industrial safety, and sexual assault. — praxis

Maybe, but without judging the value of the things being stretched, just to judge the length of the stretch: is the above stretch between a man taking over a women’s sporting event (maybe as a precedent for all women’s sports) and child abuse/sexual assault a bigger stretch than an ad with a pretty white girl talking about have good genes/jeans and being offended by her? I’d say only the woke hear that sort of dog-whistle. But all of the girls in surfing competition (if not everyone who watched, could see what was expressly being done (no whistle sensitivity needed).

-

The imperfect transporterWe all go through an imperfect transporter, literally every moment of our lives. — SophistiCat

I agree.

There is the “Ship of Theseus” paradox -if you replace one board on a ship, it’s still the same ship; but if over time you replace all of the boards, one by one, at what point does it become a new ship or is it still the same ship after all of the boards have been replaced.

Pre-star trek transporter problem.

Like the birth of a caterpillar, then it enters the cocoon, then becomes a butterfly, orbit is the same creature?

Or the swimming tadpole becomes the tree climbing frog.

@Mijin -your line between you being transported or not is certainly an interesting philosophical problem, but I just think all of the sci-fi of transporters of scattered atoms recombined totally confuses an issue that has perplexed mankind since a person fist said “Hey, it’s me.”

Identity is the line between this and that.

Over time (or over space in the case of a transporter) the line between this identifiable one and that identifiable new one is stretched and broadened.

In a way, I am reborn at each new moment and each new moment is a brand new me.

In another way, I can only make this observation, because something I also call “me” persists and remains across many moments. It’s like two clocks are going at the same time in order for ‘me’ to recognize new “me’”.

From his own point of view, did he survive? — Mijin

See that is the problem with the transporter problem - that is a fact question. You’d have to ask him. You’d have to run him through a test transporter and ask him. What else is a ‘me’ but the one subject who reports when you ask “who’s there?” Once transported, If he couldn’t tell whether or not he died and was reborn, or died and was duplicated, or didn’t die at all, who else could possibly determine that and how? What or who would care?

You’d have to run the experiment, or just think about the Ship of Theseus. -

The imperfect transporterI am sorry but I hate this problem. Why would anyone assume the Star Trek transporter could ever possibly work? If one assumed it could possibly work, one could assume any number of solutions to any number of assumed problems.

That said, if one assumes scattering all of the atoms in a living cell doesn’t irreparably disintegrate the cell, and if one assumes one can put all of those atoms back in place and that the cell would just jump start into functioning again (why do we assume you can transport atoms any faster than whole cells anyway, why don’t the atoms need to be broken apart into light waves or something, but…), then the transport process is just me being me while moving very far very fast and the differences between me before transport and me after transport are like the differences between me before walking across Europe and me after - things lost along the way and things gathered making me new with each step.

there has to be a line somewhere between "transported" and "not transported". Because, while "degree of difference" might be a continuous measure, whether you survive or not is binary — Mijin

I think that is the age old metaphysical question of identity and change. Transporter or not; surviving or not - these are ways of saying “what is ‘me’ when ‘me’ is a changing thing?” What about “me” survives one minute to the next no matter what process of change is occurring?

The fact that you can say things like “Abe Lincoln appears at the destination” makes the whole thought experiment utterly impossible to help think through this metaphysical issue. What is “Abe Lincoln” in the first place is the same question as “what appears at the other end of the transporter”, which are the same questions as “are what appears at this end of the transporter and that end of the transporter the same thing or two different things.”

The question is “what is an individual thing, or, what gives it an identity over time?”

This is Aristotle, or Heraclitus. Transporter confuses the confusing issue further. I think. -

The End of Wokeemotions are forms of judgment: They aren’t just feelings or reactions; they involve interpretation, appraisal, and meaning. — Joshs

Emotions are not just ways of thinking or judging, they are pre-reflective ways of being in the world, shaping how things matter to us. — Joshs

This is all very clarifying, but I think I disagree with some of the distinctions being made.

I would say judgments take account of emotions, but I don’t see how emotions could possibly be a “way of thinking or judging”.

Emotion is a psychological condition. It is like the body or the brain, something in which conscious thought sits. Emotion is disposition, and situates one’s conscious thought in the world. Emotion is like a higher form of sensation.

It can’t be a “way of thinking”. Emotion can be conceptualized and considered as evidence when thinking (but emoting itself is not a type of thinking). One can make judgments to follow the flow of emotion versus stopping to further deliberate and introduce concepts and other reasons. One can choose to go with one’s gut feel and not think too hard about something. This can be the best way to proceed (it’s a judgment call whether to think or not.)

The moment where a judgment is made, one is willing, intensional, about some mental object of thought. One judge’s the deliberation is over, enough evidence has been correlated into a coherent judgment, and one judges. This is reasoning or thinking - intellect and will in operation. But the moment of judgment is the end of this moment of reason. We sense - we reason - we judge. We gather experience through sensation, emotion and conceptualization; we reason about these and deliberate (forming many interim judgments); and then we make the ultimate judgment - we stop thinking and otherwise act.

One feels scared as one senses an angry bear, but one further observes the bear is focused on something else and one reasons the bear is not aware of you so one can judge what to do next. Feeling scared is important evidence to do the right thing. We can short-circuit to the moment of judgment and act immediately out of fear - but in doing so, this is not a “way of thinking” but is not thinking at all. We could also swallow our fear, and be courageous and stay still and quiet to think about what to do next.

There are not two different tracks or circuits here that we judge which to follow. We don’t act on emotion OR act on reason. Emotion is always there, like the body is. We are on one track and either incorporate sensation, emotion, AND intellectual activity all before judgment, or we skip one of these steps.

One can see the American Eagle ad and immediately feel outrage, and act angry, and try to construct an argument about how outrage is reasonable or go protest, or deliberate about what is happening to you by this ad before acting at all, before judging your emotions are reasonable evidence of the world and state of affairs. -

The End of WokeYour position, like that of Leontiskos, harks back to an older way of thinking about this relation, wherein emotion and reason run on partially independent circuits, and emotion can distort or inhibit rational processes of thinking. — Joshs

I think my position is less clear than that.

I would say that reasoning is an act of the will and the intellect. A synonym for “to reason” would be “to deliberate”. So will and intellect must simultaneously be at work to reason. Emotion can consume the will or, like a stoic, be subsumed by the will. So emotion is not on a parallel track, or prior to, reason. It’s all in the mix.

What I describe is not very clear, even to me, but I think it is more clear than what I see you describing of Deluze (who I’ve read a little) and Witt (read a bit more). I see carts and horses being moved around, but not much clarity regarding independent circuits being identified. -

The End of Woke

A critique or even assessment of wokeness can feel ad hoc (and therefore unsympathetic) if it is not situated within a broader theory of error or understanding/assessing. — Leontiskos

That should have been more plainly said by the critic of the critique/assessment. Are you trying to be woke about criticizing wokeness?

perhaps it will help for me to acknowledge that the general error of the woke is not only found elsewhere, but is actually the basis for almost all bad/evil acts of judgment whatsoever. — Leontiskos

True. So maybe what is peculiar about “wokeness” has not been peculiar at all? “Woke” is merely a new window dressing, a new word, for erroneous justification of emotional conviction?

many of our decisions become automatized, almost unconscious. This condition affects not only those identified as “woke” but all of us. Woke individuals primarely remain anchored in a relatively localized domain, where they can continuously demonstrate their vigorous sense of moral rightness and commitment to justice. In doing so, they vividly illustrate how rationality can become subsumed by the impact of ‘the short-circuit’. — Number2018

I think all of this all makes sense, and should continue to be fleshed out, but I also think we may be unnecessarily leaping ahead.

Woke is peculiar. Woke is not just a general neglect of reason, but a particularly focused liberal/progressive brand. Have we defined it enough to go so general as to all error theory?

Eichmann's reason became a slave to his passions, at least if we see Nazism as part of his passions. — Leontiskos

So we can find the same kind of error building leads to following and promoting Nazi ideology, as might lead to following and promoting woke ideology.

Eichmann’s work duties amounted to a network of language games authorized by a form of life which made his work life intelligible to him both practically and ethically. — Joshs

This seems to position things not in emotion, but in a stipulated rational framework called the Nazi.

Affect cannot influence rationality from below — Joshs

Is this a reframing of the source of error? Or are we moving away from error making? In which case we are drifting from our thesis it seems. @Joshs how do you think woke or Eichmann avoid error and emotional trigger.

However, for Deleuze and Massumi, as well as according to Foucault's concept of power-knowledge, affect is the necessary condition of reason and deliberation. My position is that true progress in thought requires an acknowledgment of how we, and our thinking are impacted by the same affective forces and assemblages that shaped figures like Eichmann or contemporary "woke" individuals. This is not a moral equivalence but an ontological and epistemological commitment. Affective investments shape all subjectivity, including our own. — Number2018

Bringing it back home again to the thesis.

So we no longer need care about what is different between “woke” and “Nazi” in order to discuss this subject?

I think error theory is essential here - wokism is error obfuscation. And wokism puts emotion first. But why would the wokist and the Nazi come to such opposite conclusions?

If emotions only, is it random whether a willfully neglect person will become a Nazi or woke?

I mean, both use similar tactics in promoting their ideology, so maybe they are only separated by circumstance? Emotional error makers born in Germany around 1915 who hear Hitler speak are more likely to become Nazis than progressives, and emotional error makers born in America around 1990 who hear the TV and go to school are more likely to become woke? Is that where this analysis is headed? -

The End of WokeI’m curious if you think it would be appropriate for wokeists to ignore something like this: — praxis

That’s an interesting way to frame the question.

I am totally interested in what you think something like this is.

I can’t imagine how to go from what this ad says/means, to what this ad REALLY says/means, to whether that is something that either demands response or that can be ignored.

The notion “good genes”?

Yesterday I was talking with my cousin about heart disease in my family, and then with another cousin (different genes) about who is tall in our family. In both conversations the phrase “good genes” came up.

I barely get the pun - she has “good genes” because she’s pretty I suppose. Is there something more I need to know about the model? She’s white? White people can’t say “genes” anymore? So if the ad only had people of color in it, they would be allowed to make this pun to sell jeans?

Yes it should be ignored for two reasons:

1. It takes too much effort and racism inside someone to be offended at this ad (at least she’s not naked) so they should fight to resist that racist urge and ignore the ad.

2. Giving it any attention at all only promotes American Eagle, so if you can’t help yourself but find something deep in the ad that is offensive to non-white or non-pretty people, it would have been better not to repost the ad and talk about it and get it in the news.

But outrage attracts in own attention and gets clicks and likes - so have at it - seems like a minuscule issue that could easily have been ignored and makes the “woke” look bad. Again.

Wish you would say what you think. Why is it something more than a silly pun on “genes” - what is it really saying that is offensive, so much so that it is not appropriate for it to be ignored? -

The End of WokeA kind of short-circuit occurs in the judgment such that one goal is prioritized to such an extent that other goals are ignored — Leontiskos

That’s what I’m getting at with the comment about the lack of wisdom. The emotional response to systemic power differences usurps good judgement.

ADDED:

that neglect is volitional, albeit indirectly volitional. The short-circuit is favored. — Leontiskos

Yes, like we all do in adolescence. This is how to avoid reasonable discussion. Willing disregard for the reasonable, and anger at the annoyance. -

The End of Wokethey remain at a primarily descriptive level and lack sufficient explanatory power. — Number2018

I agree - I am more analyzing the effects caused by wokeness, than I am getting to heart of what it is, what drives the emergence of these effects.

apply a theory of affect to approach wokeness as an affective phenomenon. Its rituals of calling out and moral absolutism reflect a particular mode of being, a form of emergent subjectivity. — Number2018

I like it. It’s why my instinct was to place emotion as the first point.

I think affection is at the heart wokeness.

So we leave that fixed as the number one component of something having some explanatory power.

I think an impulse to resist, which may be emotional, needs to be analyzed. Like an adolescent psychology - the first impulse of the woke when perceiving anything as coming from the powerful is to say “No - I disagree, I will resist.”

They have a built in power-detecting filter.

This forces reason, and discussion, as secondary to the emotion. So this further elaborates on how the affective phenomenon plays out.

But I think reason and discussion and argument are at the very heart of being human, so if we do not understand better how the affective creature that is a woke person reasons, we won’t fully explain the phenomenon.

We can’t just say they are guided by emotion, because they use reason and argument all of the time. We need to think through the fact that the woke are as fully human as anyone - I love them too, but they are just wrong - how?

I think the key is wisdom and judgment - the woke, like adolescent, simply lack an interest in learning and cultivating wisdom. They think as the the adolescent thinks that, because some bit of enlightenment is new to them, they are the first person in history to come up with wisdom and so they don’t need to listen to others. And besides, wisdom always seems to come from the powerful, and because they impulsively resist the powerful, they just don’t hear the wisdom from them. Wisdom and “my truth” are mine first, and maybe from those people I like (peers).

So they can be intelligent people, even skilled at logical argumentation, but the objects they argue about or judge to be important are just not always apt.

They view a lack of clarity as an openness to diversity, when it may just be a lack of self-awareness about the fact that they don’t know what they are talking about. That’s poor judgment. And instead of finding wise leaders, they dig in on some hill.

The woke see two things, and look for which has power over the other. It’s sort of a baked in reality that is most important to them - victims and oppressors are absolute and everywhere where two things sit next to each other. They hate this, and so fight for egalitarian leveling. But they don’t take time time to discern what can be equal and what cannot. They don’t ask which one between the powerful and the powerless might be good and which might not matter. The oppressed always matter more, and the powerful always only abuse and oppress. This is poor judgment.

This is why woke feminists can’t integrate with woke trans, and why racial motivations made Obama outshine Hillary in the 2008 election. Racism is a deeper hatred and more impactful fight than feminism (at the time). And now trans is more stark and better battle than what “woman” means (trans is at war with race as well). Since women now have power over transwomen, women may need to be resisted and take men down now.

Wokeism doesn’t really have the criteria built into itself to ensure justice between the feminist and transactivist. They just hope they can feel their way to the right villain and take them down.

It’s poor judgment finding poorly designed categories for sake of barely identified goals, summed up as fight the power.

So, there is not only an affective explanation, but a judgmental resistance to the logical if that logic comes from a station with power. -

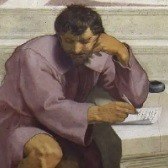

The Christian narrativeBasically, any relation that can mean anything at all involves three things:

-An object that is known (the Father)

-The sign vehicle by which it is known (the Word/Logos, Son)

-The interpretant who knows (the Holy Spirit) — Count Timothy von Icarus

Now, science often tries to view things a dyads, but it does this with simplifying assumptions and by attempting to abstract the observer out of the picture. There ends up being problems here for all sorts of things (e.g., entropy, information, etc.), but more to the point, true dyadic relationships don't seem to appear anywhere in nature. Everything is mediated. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Love it.

I find this actually flows from Heraclitus:

1. Harmony/tension, flows from 2. this, and 3. Its opposite.

(And of course he acknowledged the logos that endeavors to mirror this, or to be held in tension with it.)

And Aristotle:

1. Matter/form, 2. Material informing agent, and 3. unifying final principle (where matter and form can first be intelligible as distinct from one another; the final cause is what allows the agent to see “not this matter, but that matter is necessary, to make this form, not that form,” so it is here that we can elaborate on number 1 being separated into two distinct causes - the first semiotic product of the ontologically real.)

Or for Aristotle:

1. A substance, is 2. an essence, 3. that comes to be.

Trinity is fabric. The triad is the One. (Can’t really be said logically, but is necessary ontologically before one might say anything at all.) -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingThink of experiencing a flow of events as a bit like watching a film. For something to be happening at all, the viewer makes a connection between each frame of the film, spanning the small differences so as to create the experience of movement. But if there is a completely new viewer for every frame, with no relation at all to the prior or subsequent frame, then all that remains is an absolute unity.

That is brilliant.

For all to be swept up in becoming, ALL cannot be swept up in becoming. We have to put a pin in the intuitive notion that “all is flux” in order to have the intuitive notion that “all is flux.”

(What is odd but I think worth noting is that very much the same arguments and points have to be made on threads about theory of mind as in theories of motion/essence. The same or similar paradoxes and same difficulties with making clear linear arguments abound in notions of mind as in notions of what the mind experiences. But the above analogy is clear, and I would love to hear what a Hume or a Heraclitus might say in response.)

But information theory deals with "what something is," and not "that it is," essence but not existence. It skips the former. We can see this in the fact that a perfect set of instructions to duplicate any physical system would not, in fact, be that system. A perfect duplicator, call it Leplace's Printer, needs both instructions and prior existent materials — Count Timothy von Icarus

This another example of the problem of the One and the Many. Instructions (the one) fail to explain the duplicates (the many), but how the many duplicates can be the same instructions is not clear either. -

The End of WokeLet’s assume that I am uncertain about what woke is — Antony Nickles

@AmadeusD

I finally get it (I think). You are looking for woke criteria. You are saying to the Board “we need to appoint a new member and want to make sure we are being woke, enlightened, in our selection, so, how do we make a woke selection?

Correct?

What is uncertain about the topic of this thread, wokeness? Curiously enough, this thread has some of the strongest consensus I have ever seen on TPF. There is very little uncertainty of how to proceed. People from all different philosophical and political backgrounds are agreeing that there are problems with wokeness, and they are in large agreement on what those problems are. — Leontiskos

That’s why I’ve been saying let’s dive in deeper.

What’s been said about wokeness.

1. It’s goals are chosen and driven more by affect/emotion than by rational analysis. (So a gut feeling on a board member is just as or more valid than some rational argumentation and comparison between two members. Who’s got the stronger gut feeling despite counter factual reasons and arguments.). Gut feelings are important factors, so I’m not against recognition of emotion and passion. But, to me, it only wins the day when all else seems equal, and shouldn’t come first. But it’s number 1 for wokeness.

2. Diversity is an end in itself. In groups of people, regardless of any other factors, diversity as an end in itself is good. So any group of 10 white men is worse than any group of 10 diverse races.

And further, diversity is defined based on surface features - the diversity between a poor southern white redneck, and rich white east coast northern city-born CEO, is not as diverse as between a black boy and a white boy born and raised across the street from each other at the same schools. Giant universal categories like race, ethnicity, religion, sex, forge stereotypes that can be assumed about all members who on the surface appear to belong to said group.

(So for the board - how many white people are already on it? How many women? How many different universalizable groups of people do we want or need to show by a quick glance at a web page our board APPEARS to represent, because the appearance of representation can be just as, if not more, important than whatever that person might actually represent.)

3. Righteous indignation. The woke are honestly compassionate for victims. But they are terrible judges at who victims are and why victims are being victimized. This goes to number 1. above. They let emotions guide their sense of how to respond to something. So they see immigrants being deported, and hear of families being separated, and hear of a person being deported with no due process, and often, the outrage leads them to think of protesting and venting that rage and making a statement so that OTHER people might change their behavior and OTHER people might keep families together and OTHER people might use due process, and seek to make new legal policy and rage some more and blame OTHERS for failures. They could go find out why families have to be separated, or find out how to enforce laws and keep families together, or find a family of immigrants and help them and put all energy into that one family, or find out what due process is and find out how it looks when it is being followed and find out how it can be improved if indeed it needs improvement, and find out how best to police the police and make sure they are following the law as well (or just throw rocks at them).

(As far as the board, how does one express righteous indignation right now when selecting a board member - this might be a sort of sabotage move where you hire a board member you know will annoy the current white chairman of the board - so you think the current chairman is really a racist, so you demand the board confront its racism and hire an immigrant black/hispanic woman. Or maybe the board are all already fully woke so the best way these days to make a big statement of righteous indignation is to parade a trans woman around - nothing says “I am righteous” today better than a drag queen who means business.)

4. This all goes to the fairly recent notion of “virtue signaling”. Wokeness gave birth to this concept. We have to look woke, while we are being woke, and in order to make sure people know we are woke we have to send signals. We wear a mask or get a covid vaccine regardless of the science, but mostly because we want to signal which group we belong to and which group are people who we don’t like. And we can scold those we don’t like because of our emotion and righteous indignation.

5. Self-contradiction. It seems to be a feature of wokeness.

You have to be racist in order to notice or care that some group is diverse or not diverse.

Inclusion and tolerance are huge righteous virtues - yet the woke are the most intolerant people and create the most exclusive clubs around.

For wokeism, there is this sense: “if loving my woke ideals is wrong, I don’t want to be right.”

This means they are allowed to argue and defend their positions with logic, but they don’t have to. When logic fails, only facists would care, because the woke are already righteous in their feelings.

(Let’s say the Board currently has all black and Hispanic people on it, some women, one of whom is white, but she is mixed Asian…it is still not woke to say “we need a white man”. A white is never needed for sake of diversity. That’s wokism being self-contradictory.)

Another self-contradiction is how progressives find dog-whistles everywhere (recent American Eagle jeans ad) - they are paranoid about conspiracies around every corner. Yet they think anti-woke people are the stupid ones who fall for all the conspiracies and mock “birthers” and “anti-vax”.

Another is about science. The woke say the anti-woke are anti-science, but both sides pick and choose only the science that supports them, and if I’d have to pick a side that was more reasonable and moved by proven facts, it would be the non-woke.

6. Everything is political. We can’t interact in the community without simultaneously making a political statement about our values. If a white man is mad at a black man, it must be because of systemic privilege in which the white man has been constructed. It can’t just be because the particular black man was an idiot, or the particular white man is the idiot, or both. This robs the black man of his ability to just be a man who can legitimately piss off another man, but that’s ok, because whether the black man knows it or not, he is a victim of systemic racism. We all are pawns in a system of politics.

When a woman isn’t paid as much as a man, it is by default, injustice, because of the structure of society.

Fathers leading families is nothing more than oppressive custom.

Everything must be turned over for sake of new policy and new system (with no sense or vision even needed for what that new system would look like).

If a girl likes being beautiful and attracting boys and wants to be a mother most of all - blasphemy! She knows not the new politics!

(For the Board - we must ensure our new Board member gets across the right signal politically, shows the world this board is on “the right side of history” and captures the politics of the current moment - basically, to be woke - the board needs a trans person, whether woman or man depends on who is already on the board, and race may not matter depending on who is already on the board. After that, we can look at leadership qualities, experience and, you know, if they will be able to function day to day on the actual business…) -

Language of philosophy. The problem of understanding beingWestern philosophy, from Parmenides to Heidegger, sought the essence of being—eternity, phenomenon, givenness—relying on the formula "Being — is," rooted in a language where "is" fixes being. Even the understanding of God—from Kant's highest being to Heidegger's mystery of being—followed this logic. — Astorre

This is a great way into the issues, and interesting analysis of being/becoming. Language forces our thoughts into certain shapes, that force us to think certain ways. And this can inhibit deeper, or broader, or more complete understanding.

Essence has captivated the west. Perhaps (in part) because of the structure of our sentences.

But I think all of the puzzle pieces and all the same moving parts of experience are written into eastern and western cultures and philosophies. Some puzzle pieces are just more the focus here or there, or then or now - but it is always the same puzzle, and always the same pieces.

Your analysis shows you looking both ways at once (west and east seeing themselves hiding in the other), and a way to educate (east teaching west about the being of becoming, and west teaching east about the essence in existence.

Very interesting stuff.

Aristotle sometimes gets lumped in as a key purveyor of "static being" or "substance metaphysics," but, were I forced to lump him into either category, I'd probably place him on the "process metaphysics" side. Hegel would be another example. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree with that too. Aristotle understood the being in becoming (or the becoming of being) better than Plato seemed to, and Hegel, for all his orientation toward the absolute, is more of a method and process developer, than a substance (absolute essence) identifier.

The absence of the copula "is" makes the question "What is being?" alien. — Astorre

Being isn't a "what".

So a language that can't even ask this question may have wasted less time. Being resists definition, and maybe need none; things that are being are the things that have definitions. The being of those things needs no definition. The definition of being is always the same - becoming...

The Russian language disrupts this logic. In the present tense, the copula "есть" (is) is not obligatory: "Сократ философ" (Socrates philosopher), "Он доктор" (He doctor), "Я студент" (I student). Being does not demand confirmation; it simply is present. — Astorre

I agree "is" does not seem to distract from the "what", which is more pure. Whatness. Without distraction. Simply present. Letting the being continue breathing and not packing into a stagnant what through sentence structure.

which points to the world as a flow where everything is born and transforms. — Astorre

Being born, is a becoming motion, so in a world as flow, you should say "everything is born already transforming, continuing to flow."

In further sections, we will endeavor to philosophically clarify whether this distinction is truly rooted in ontology or if it is merely a grammatical intuition. — Astorre

I think it is a bit of both - the languages formed differently when similar human minds spoke of the similar experiences of the same world. But the eastern and western optional ways of speaking were there for the codification all along.

stemming from the Problem of the One and the Many. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is universally acknowledged, isn't it? Maybe not as a problem, but a concern, something drawing the attention of everyone who pays attention. The one-many, fixed-changing.

Being, in our view, becomes through the establishment of boundaries, through the interaction of presence and change. The question "Being — is. How?" is replaced by another: "Being — becomes. How does it become?" — Astorre

You are ambitious. I love it. Interested to see what else you see. -

How do you think the soul works?

I am not disagreeing with you or with the excerpt.

This is a language problem, not a misconstruing of what things are (and what things are not).

We should not say “the” mind.

We should say “minding” as a verb, or gerund.

The saying “make up your mind” is when or how (not what) a mind is.

Mind comes to be, thinking about.

See the seer of seeing.

Mind the minder of minding.

We cannot do it, yet here we are doing it.

Mind, as thing, is paradox. Impossible, in the act of constructing this impossibility. -

Opening Statement - The ProblemThey will complain of straw men, of trolling, or simply of rudeness, apparently being astonished that folk could be so discourteous … — Banno

Or they will say thank you… -

The End of WokeA similarity in the two is that both a surfer and a board can decide to hang 10. — praxis

Next top surfer title has to be - “The Chairman”

Or do we allow men and women to compete together and name the victor “The Chairperson”.

The trophy can be someone standing on a conference room table, hanging 10. -

The Problem of Affirmation of LifeHow can life be justified in spite of all the suffering it entails? — kirillov

I don’t know - if there is no miracle coming, and life was intentionally inflicted on us, then maybe it can’t be justified. If life is a big accident, then it doesn’t have to be justified.

But I don’t know, besides God.

Do you wish you never suffered at all, and no one else did, or do you wish that you and everyone else never suffered again?

If you only wish you had suffered less, that is not the question and so not an answer. We already do suffer less, and more, as each comes and goes.

But do you wish to never have suffered at all, or do you wish to live with relief that is permanent and thorough? -

The End of WokeWe can also abandon the experiment, if that’s what this means; or just try it out. Your call. — Antony Nickles

I didn’t mean to imply abandoning the experiment.

I guess I’m saying it needs more structure (in my eyes) to ensure it is even related to wokeness, and the way I propose giving it that structure is with a bit of dialectics - adding some Yang of goals, to the Yin of assumptions and criteria, to then come back with a new synthesis and re-inquire about the assumptions and criteria (the experiment).

But to recap progress (I’ve asked the secretary): we are seeing criteria reflecting assumptions in the identification of: general lived experience, leadership, practical task at hand experience, moneymaking/fundraising, goal setting. I see some methodological awareness of a distinction between judging, and understanding, and some thing understood. (But we haven’t really fleshed that out yet).

That’s all mostly Yin. Method. Criteria. Not many assumptions made explicit.

I’d like to provisionally “cash out” this just to see what happens - to see if the experiment is going to help us at all to understand wokeness. I am losing sight of that. OR maybe there are tons of assumptions YOU have in mind that make all of this clearly about wokeness. Please put them on the table.

But to continue building the experiment I’ll call “How to Build a Better Board”:

What kind of company? This will matter. Is it an American based for-profit, publicly traded mineral and mining company with 5,000 employees whose business model involves trashing third world resources? Is it a non-profit think tank aimed at educating HR departments in how to foster DEI? Let’s go more neutral, and say it’s a small business (200 employees), that makes low cost baby and children supplies (whatever that means, doesn’t matter to me more than manufacturing/selling kid stuff). So a nice little retail/manufacturing start up, privately held corporation, struggling to grow in today’s marketplace. (Or you tell me if this kind of detail is not necessary and I’m way outside the intended experiment.)

Do they currently have 5 board members or 12? This matters because a board of 5 members leaves no room for error and each member will have hands pretty full or all will share all duties (just operate differently than a board that has room for sub-committees). Lets say they have 7 members, all of them have some degree of ownership (profit share) in the company, but there are more employees who own some of then company that are not on the board, and the Board is looking to add an 8th board member, and don’t care if they are an owner or not. (Will this new even number of 8 members allow for stalemates in voting? so do they need to consider adding 2 members and bringing the Board to 9?)

And how about this specific - which brings up age-ism - the current Board and leadership recognize the company needs a bigger and better online social media presence. Want to almost become a baby-stuff influencer as a company. Do they make someone young and fluent in social media a board member? Even if a candidate happens to be great at social media, if they are over 55, it just won’t give the appearance they want for the role. They want a mom or dad, not grandparent type, dare I say. This new board member is going to develop initiatives that involve both their employees internally (stuff to post about in the company) and they have a lot of young employees, and they will have a bit of a marketing role themselves, be a face for the Board, so a younger face makes the sense (but no one is sure it’s necessary).

Am I getting us anywhere? -

How do you think the soul works?An object, exists.

An object has an ontology.

The mind knows objects, so it makes sense to say the mind is therefore other than objects; the mind is not an object but an objectifier of sorts.

But holding that thought, could the mind be a different type of object?

'It is never seen but is the seer; it is never heard but is the hearer; it is never thought of but is the thinker; it is never known but is the knower'. — Wayfarer

I think the above mystical quote is more about epistemology than it is ontology. It is both. But the ultimate point may be that when we take the mind as an object, we have to actually make something other than a mind to retake as an object, so that we might know the mind indirectly. (Like we know all things indirectly. — epistemology…).

the unknowable nature of mind is something it is important to acknowledge and be aware of — Wayfarer

If you read this all together it makes sense. If you break it into parts, it becomes impossible to form a single sentence out of it.

You said “mind is something”. In order to show mind is not some thing.

You said it is an “unknowable” something, and that this unknowable nature must be “acknowledged”.

This reflexivity about impossibility is ubiquitous when speaking about the mind. Acknowledging something about the unknowable, with the mind, that is that same unknowable thing, and with the mind that is not a “the X”.

It makes it impossible to speak of without mystical non-linear reasoning. Or metaphor.

Mind is like an unmoved mover; once we say something about it, we’ve made a move, and so moved away from it.

You’ve heard it said that thoughts are in the mind - well I say it is the same thing to say that the mind is constructed by its thoughts.

To say the mind is empty is the same thing as to say there is no mind whatsoever.

It could be said that the mind is where knowledge resides. It can equally be said that the object that is known is where the knowledge was drawn from by the mind. Knowledge, in the mind, is always knowledge of something that is not the mind. (This is why knowledge of the knower is so elusive.)

Like looking in a mirror - we see it is us, as it is a reflection from us, as so it is not us, but it is a reflection of us. So not one of these, without all of these.

I find it is just as hard to accept both or either truths: that the mind is not an object, and the mind is an object. Because the mind is the object that isthe ground of experience, — Wayfarer

So I don’t want to disagree with anything you said about mind; I think, mysteriously, maybe paradoxically, I want to add knowledge of the mind that somehow there is an object there when the mind is being a thinking mind.

It’s like you have to know both that thinking itself is never an object of thought itself, but also, like Parmenides would say “it is the same thing to think as it is to be” such that thinking is the only object.

Ontology and epistemology overlap in the act that is mind.

Overlapping is like reflection.

Reflection is the best single noun.

Because reflection is many moving (conjugating) parts, but one part.

I say these things hoping better minds can make use of them.

the source from which knowledge arises. To mistake it for an object among objects is to lose sight of the subjectivity that makes knowledge possible in the first place. — Wayfarer

Does, per Kant, knowledge only arise because of the mind? Isn’t is also knowledge of some thing? Admittedly that thing is first shaped by my senses and by the conditions of experience, but it is still an experience of some thing (not pure idealism - in which mind is the only thing).

I think that it is right that calling a mind a thing is to lose sight of subjectivity. But that is the thing about the kind. It is like a mirror but a near letter t mirror, meaning when one looks at oneself, when the mind reflects its contents, the mind sees both the contents and itself, like looking in a window and seeing yourself on the other side as if it was a mirror.

The mind is both subject and object, when the mind thinks about itself.

It is not perfect - we don’t know ourselves completely. But we know some thing when we know our own minds. -

The End of WokeA board hires someone who will best contribute to their goals

— Leontiskos

Okay, but how they decide (what is important in deciding) is based on criteria. Contributing to their goals is one criteria (do we have a goal that each other criteria satisfy? — Antony Nickles

Okay, but you need to cash this out. What does this have to do with wokeism? Are you demonstrating how woke thinkers think, or are you coming to a woke conclusion, a woke thought, somewhere in there?

I don’t think this expressly needs to have anything to do with woke yet.

A board hires someone who will best contribute to their goals. The rest of your post is based on assumptions about the different kinds of goals different kinds of boards would have. But like my other questions, I don't know why we are pretending — Leontiskos

A few posts back I raised as an interest or goal that all people are individuals, that kinds of people or groups are less important than any single individual that might be placed into the group for sake of argument.

This to me is an unwoke interest. Nothing came of it because you wanted criteria and underlying interests.

Now with the Board example, as with my individual example, I will still prioritize the particular when seeking the criteria and/or the interest/goal - I sort of, assume a criteria and find some particular with it and augment the particular by expanding the criteria.

So I can’t even begin to balance Board criteria without just discussing the particulars.

What kind of company/entity does this Board lead? For profit or non-profit? What is the product or service?

Who is on the board already? Who is being replaced, or is the new person being added?

These particulars are mostly external to the new potential Board member. The criteria you mentioned are mostly internal to the person:

history of leadership, subject-matter or practical experience, the ability to contribute to the board's goals (say, fundraising, lobbying), connections (political, celebrity). We may need to elaborate how judgments are made on those criteria with examples — Antony Nickles

These are about the new individual. Before I can start to prioritize and identify these people factors, I need to know the company, service, physical pieces…

But let’s look at what you said. One thing is the different notions “leadership, experience, moneymaking, goal setting. The other thing is “how judgments are made.”

@Leontiskos mentioned a third thing about making judgments, or understanding.

So in another prior post I talked about doing two things at once (like answer why and how, or clarify goals and criteria as @AmadeusD mentioned.”

Now in this post here, the method now becomes doing three things:

Criteria. (Substance based X)

How judgements are made. (Reasoning).

Judgment. Or understanding. (The particular truth, universalized, or simply what is now known.).

So we have some criteria and underlying bits. Now let’s talk woke or not-woke with these bits in mind.

Is your point with the board that if the company serves some group—say a minority—then that minority should be represented on the board, and that this therefore has something to do with DEI? — Leontiskos

@Antony Nickles Is there a way to promote inclusion, without first dividing different exclusive groups and identifying types of people to be included and represented, and others to be excluded as already represented enough?

Is there a way to promote equity without blindness to particulars?

Is there a way to promote diversity without recognizing all of the inequities that make things diverse?

When are we going to cash this out in terms reflecting the woke?

Let’s just pick something important, say what and how that is the case, and see what criteria emerge in the process, so that next time when we pick something else important again, we’ll have stronger criteria. Let’s go back to the topic, criteria be damned )before we damn the toooc and review the criteria again…) -

The End of WokeHis argument might be <There is a communication breakdown; if we take a step back and re-evaluate our interests we might overcome the communication breakdown; therefore let's take a step back and re-evaluate our interests>. Or if we are going to set an issue before a board or group of people we might want to establish criteria beforehand according to this argument: <If we explicate our criteria for a decision beforehand, then we will be fortified against post hoc rationalization once the arguments begin; it is good to be fortified against post hoc rationalization; therefore we should explicate our criteria beforehand>. — Leontiskos

@Antony Nickles. I think we are trying.

this meta-topic, because it is quite prevalent on TPF. Much of this will build on what AmadeusD has been getting at. Often on TPF people of a certain stripe try to talk about criteria, or frameworks, or something else as if they are presenting a wholly neutral starting point — Leontiskos

Yes. Instead of talking about some thing, we end up talking about how to talk.

I fully admit the criteria and the step back is important. It’s like putting all of the products on the shelves and giving them a price and having a cash register and hiring the employees and planning for opening day. All vital. But we never get to opening day and to cash out any of the criteria or see what products sell and which don’t and see a customer smiling as they say “thanks”.

We never conclude something together.

It’s all back-office paperwork.

I think it’s unconscious.

I also think it is a characteristic of woke - if the other party doesn’t appear to agree with you, they must need to reevaluate their whole approach so let’s talk about that instead of whatever thing we both disagree with.

But, I would rather discuss whether woke avoids direct confrontation every time - meaning argument (the woke obviously love a good protest, but they seem to hate a good disagreement.)

Or how about whether woke or traditionalists seek to verify the facts more. Both sides accuse the other of making up facts - does either side do this more often than the other (both accuse or actually use, false “facts”)?

Or we can start with a traditionalist thing - Leontiskos called wokeism heresy, and @praxis saw this as counterintuitive since woke and Christ seemed to both root for the little guy, the down-trodden. How can Leon’s heresy claim be consistent, or how come the religious are not more woke? -

The End of WokeMy point is that the idea that hierarchical thinking is an evil bogeyman is a strawman. Anyone who admits that some values are higher than others is involved in hierarchical thinking. It's just not about power stratification. The power hermeneutic is something that the woke imposes on everyone and everything. — Leontiskos

That’s what I was saying.

and simply acknowledge the absence of a state and organized religion, yes? This, in my opinion, loosens the rigidity of the bishop's hierarchy of values — praxis

I don’t know that we have any idea of what people did in a time before political and moral interaction, community narratives and stories of the dead and the invisible but apparent forces. There has always been a type of political state as soon as more than one family create a clan, and there has always been a type of religion as we see burial rituals going way back in time.

Plus you are placing an interest in egalitarianism over and above an interest in hierarchy - thereby creating a hierarchy.

So why fight the hierarchy itself? How about instead we focus on setting the right ideals and goals at the top? -

The End of WokeWhat do you have to say about the fact that for 95% of human history — praxis

I’d say 95% of human history covers hundreds of thousands of years possibly, and we have scant evidence of what the moment to moment lives of those individual people were like, other than, if they were people, they found themselves dealing with hierarchy everyday. How certain are you about egalitarian hunter/gatherers? You don’t think some people consistently gathered more food than others, and stratification wasn’t considered all of the time??

I didn’t listen to the bishop. -

The Christian narrative

Well since you say things you don’t mean like “humanity is evil by nature” and then don’t explain why anyone needs to know that or how it might relate to you OP, I’ll let you you know, since you don’t know, I am right. You aren’t serious. Not so much “all is lost we are doomed” serious, but sort of “this is interesting” serious…which you are not. I was right. -

The Christian narrativeHumanity is evil by nature and must atone for its sins. — frank

That’s a funny joke. Right? I mean, not so much “haha!” funny, but sort of “hmmm, I think he is kidding around” funny. It’s a form of mockery, if you will.

Because “evil” and maybe “by nature” and “atone for sins” are figments, right? Or am I the stupid one here?

Or are you the reincarnation of John the Baptist, if I may mix religious imagination (which I can’t see why you would mind that)?

Because humanity is not evil by nature. That’s just stupid. You’d have to explain how that is possible or what that means. Sounds dumb to me though, I’ll be honest.

You may need to see a psychiatrist. Because I never would have predicted such behavior as this post if you are serious. (I’m kidding of course. You’ll be fine.)

Or are you sane, and serious and you have really sinned…? In which case, I’m sorry for your loss, and you may be in big, big trouble…

:up: You can always look on the bright side of death… I hope. -

How do you think the soul works?My claim was the mind is not a thing. Doesn't mean it's nothing. But it's not a thing, it's not an object. Your 'experience of the mind' is not an experience at all mind is that to whom experiences occur, that which sees objects, and so forth. It is not itself an object. That's one of the things that makes philosophy of mind such a big and elusive topic. — Wayfarer

I don’t know how to deny any of that, but then there is the notion of self-reflection. Experience is what the mind does, and in that sense the mind must be unlike any of the things are experienced. But then, one of the things the mind does is reflect on what the mind does (which is unlike any other things too).

I think philosophy of mind is so elusive because the mind is at once a thing and, not like any of the other things it minds (it thinks about).

They way to experience a mind in the world like we experience other things in the world my be to experience the mind of another person. For some projects we want the minds of certain people, but for other projects, we want other peoples’ minds - these different minds are real objects distinguishable because of real experiences. And we get real results from our awareness of different minds as if they were different things.

So maybe mind or soul, to be a thing, must be bound up in a community that helps carve out and distinguish all of the different minds as now things to be experienced like other things are experienced.

I self-reflect and can find my mind needs the help of other people to figure something out, or I find my mind is sufficient to figure out this other problem.

So mind is like a thing, but not like a thing, at that same time.

But the positive contribution here is that, in order to discuss what a mind is, the notion of reflection has to be incorporated. There is something unique going on that is mind, and in every mental happening, there is a reflection involved.

Let’s pretend the mind is muscle, or a thing. When the mind does its thing I think it simultaneously does two things - it spins itself up into existence, and it fills itself up with what it is minding (thinking). So the function of mind is to self-animate, and at the same time, self-animate for a purpose or with something in mind.

This is just a theory I throw out there to hopefully make this discussion more frustrating and complex and raise more questions than answers. :grin:

I know you asked about the soul and not the mind. Soul to me is a word used as a unifying principle to integrate everything about your personhood. (What is that?). Meaning it’s like your living personality, which includes your emotions and passions and dislikes and physicality/body, and intellect and will and heart and mind - soul is all of you that matters to yourself and to anyone. Any changes made to who and what you are, are changes made to your soul, or in your soul, o by your soul. Your soul shapes your body while your body shapes your soul because you are neither of these alone both both of them at once - you are living a particular life, and that particularity is of your unique soul.

So animating principle (psuche) is a type of unifying principle. Your soul is you living, what moves you and you moving whatever you move. Soul is what is loved most in other people, and it is what enables people to love.

Other Greek words are helpful - there is nous or “mind” which is more tied to knowing and thinking (I believe), and there is daemon (from which we get demon) which is more tied to like a Freudian id, or underlying impulse and sub-conscious passion (I think).

This raises the notion of consciousness. All animals with senses display a type of conscious awareness. People are aware of their consciousness - so what appears unique to me about people is that consciousness itself is an object of human consciousness (we notice the subjectivity of others and ourselves), but other animals don’t do this (not like people do).

And this, I think, raises the fact that language itself is tied up in the soul or mind. There is something going on with the fact that only human beings, the ones who can wonder and do wonder about minds and souls, have true language. A word is a thing that reflects something else; it represents something else; it points to what the word means or names or is is used to say. So like the mind is reflection, the words the mind uses to organize its thinking, are never alone in themselves but referential and reflective of things. @Wayfarer Words, like minds, are not things. And Language is tied up in Logos (the word) which is the root of logic, which we have been using all along here to read to this post. Words only present their souls (to speak metaphorically), their meanings, in a mind. My dog doesn’t see this post has any different meaning than your original post or anyone else’s post, because my dog’s “mind” may not be a true proper reflecting mind at all.

And @Null Noir, I agree I want all of this to matter. I cannot pretend that any meaning I make for myself actually matters to me. It just sucks all the soul out of these discussions to think no one need care about anything I think, about my life. I don’t know why I would care about other people’s lives if they had no reason to care about mine, because I had no reason to care about mine, other than as a distraction from this whole question.

I’m not afraid of death - I won’t be dissappointed because when I die, I either won’t know it (because I’ll never dead) or I will learn I have been saved somehow from death.

But I believe my life matters to God. And I agree that without something more to life than birth to death, there is no real meaning to this thing. We might enjoy it anyway, but that doesn’t make it meaningful, just enjoyable. But it is because my life is enjoyable to God and other people, that it can be said to be objectively, truly good. Not because I like myself, but because am likable at all as proven because I am liked by others.

So in the end, you are meaningful, whether that means something to you or not. I hope it does. -

The End of WokeThis inversion where one places secondary things into the first place is key to wokism. -Leontiskos

Rather, the fixed hierarchy is key to power stratification that wokeness aims to reduce. — praxis

@Leontiskos

Huge.

So secondary things placed first is key to wokism.

Or, wokeness aims to reduce fixed hierarchical power stratification.

So much work to do.

I’ll start with “power stratification”.

Why does wokeism assume it must be reduced?

Is there something inherently always oppressive about hierarchy; or can hierarchy be compatible with, or even necessary for freedom and justice?

Can we question this interest first:

If “the fixed hierarchy is key to power stratification that wokeness aims to reduce”, then let’s see if that is a good goal, if that is supported by valid criteria?

My sense is wokeism judges hierarchy inaccurately as oppressive.

I can’t create an argument to prove this (someone else might), but I can give an example that allows me to judge hierarchy as neutral whereas oppression is negative, so by inference, if hierarchy is neutral, it need not be oppressive, so no need to assume so.

Hierarchy is woven into the fabric of everything and speech itself. By positing a “reduction” we still must see the higher has been make lower, and so there is simply a new hierarchy, not a non-existent “power stratification,” merely a new one. So wokeism can’t simply “aim to reduce power” (as if all power over another must be bad). If a woke person, or anyone, wants to realign power stratification, they must do just that - realign it, not simply and abstractly seek to take down all the powerful. We have to live with hierarchy and need have no interest in defeating hierarchical thinking and power structures - but we may instead need new representatives of the ideals or the high, and more humility from the ones who are led or the low. We aren’t just to embrace hierarchy either.

I’m not saying there is never a time to fight the power, to take down the man. Because there certainly is. But I am saying there is also I time to set up on high, to uphold a positive structure, and build up. So if reducing hierarchy is an essential part of wokeism, wokeism is doomed to be incomplete. It’s not a good enough goal.

Fire Ologist

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum