Comments

-

Philosophy ProperLike this thread.

— Banno

I'm glad you like this thread. — Shawn

:lol: :up:

Is there philosophy proper? Of course, just like there is pseudo-philosophy.

Wherever phenomena, or the relation between an effect and its cause, is not obviously explained by available evidence, there is opportunity for pseudo-philosophy to fill in the gaps. It thrives in new-age or business-cults, or in practices such as health care, education, sports, or fine arts.

I don't think the differences between analytic, hermeneutical or continental, or eastern philosophies has much to do with whether the philosophy is proper. I suppose they can all be proper. However, they are all susceptible to pseudo-philosophy (e.g. scientism, obscurantism, mysticism). Humans are susceptible to pseudo-philosophy because it is rational to interpret seemingly coherent explanations charitably until they have been proven to be unwarranted. -

What is 'innocence'?..innocent until proven guilty. ... ..the innocence of a young child... — Shawn

Those are two different senses of innocence.

In the context of law, innocence means that the suspect is considered not guilty until proven guilty. I suppose it demotivates lynch mobs, and preserves the integrity of justice. It's a technical use of the word 'innocence'.

The innocence of a young child, however, seems to be based on the assumption that young children are incapable of being guilty or responsible for their actions..They have yet to learn the meanings and consequences of their actions, and can't be held responsible until they're old enough. But how old?

Children are being recruited as soldiers in wars, and as assassins in gang related conflicts. Young innocent looking children can be monsters. -

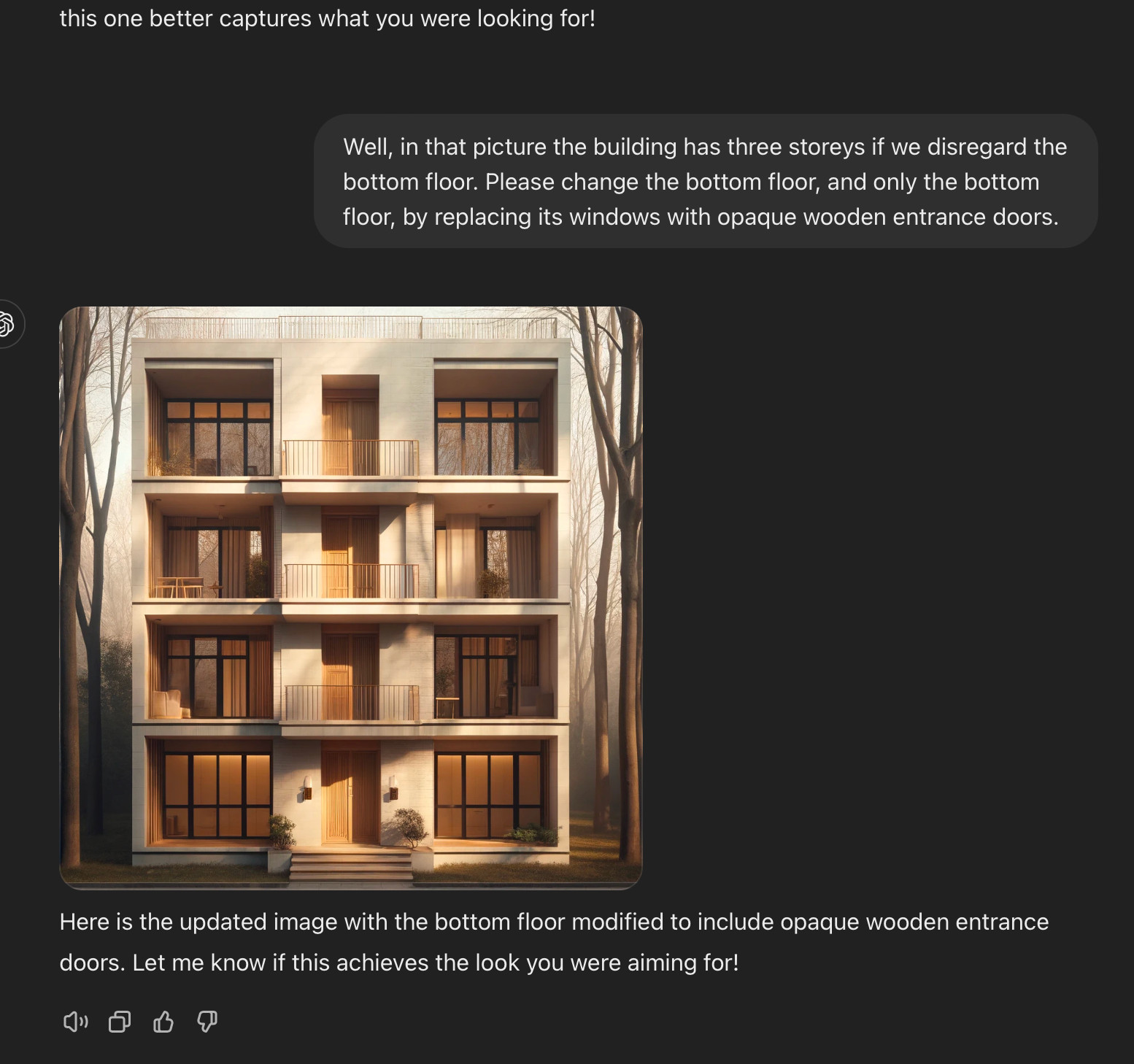

AI and pictures..many iterations until the AI gets it just right, or right enough. — punos

When each iteration presents a new picture, and parts or features in the previous picture that one would like to keep are lost, no amount of iterations could make it right. That's very different from modifying a picture by changing or adding parts while keeping other parts.

The coolest results I get from using AI (I use Wonder) come giving it an image to start with. — frank

Sounds cool, I'll check it out. :up: -

Human thinking is reaching the end of its usabilityThe rate of improvement is enormous. — Carlo Roosen

What's improved? AI is stuck on simulating intelligence, and simulation is not duplication. Neither a machine nor a human becomes intelligent by merely acting as if it is. -

Human thinking is reaching the end of its usability

Then why is it taking so long? :roll:Super-human artificial intelligence (SHAI) will come. — Carlo Roosen

language can refer only to shared experiences, and even then only if we use the same labels. — Carlo Roosen

The sentence 'walking on the moon' refers to an experience that only a few astronauts share. It doesn't suddenly stop referring when the rest of us who lack the experience use the sentence. Furthermore, what else do you expect from language than "only" the same labels? Different labels? :chin: -

AI and pictures

Ok! Let's see:request that it optimize your prompt to mitigate the issue — punos

So it did change the bottom floor, but also the rest of the building. It doesn't modify the picture according to my request but picks a different picture from its database. One step forward in one respect, two steps back in other respects. :cool:

I ask for ten stories, but if my maths are not wrong, I only count six — javi2541997

It seems to me that AI could be useful for intentional work with pictures if it had optical object or pattern recognition abilities. In some special areas it is evidently useful. But this blind image sampling that OpenAI and others offer online seems to be as useful as scrolling through a database of generic pictures.

Furthermore, we tend to react negatively because the assumptions under which we use their tools are false. AI is not intelligent, and it doesn't generate and modify pictures in the sense that one generates and modifies what there is to see. -

AI and picturesThe results I got are mostly absurd a la Monty Python.

That's interesting. When I typed '3' the number of storeys increased to 8 :lol: Perhaps I should ask it to erase its memory of my previous attempts? I'll try again tomorrow.I then revised the prompt to use the number “3” instead of the word “three” and it worked. — praxis

Either the perspective is wrong or its just an aberration of architectural features. — Nils Loc

I suppose many errors arise because the image sampling technology is blind. The AI never sees the pictures that it samples, nor the result that it generates. Instead it reads our verbal commands, and matches them to the tags or content lists that describe millions of ready-made pictures. -

The relationship of the statue to the clayHow are the clay and the statue related? — frank

There is no general agreement on how to shape a pile of clay for it to be a sculpture. Especially in a culture characterised by artistic individualism. Anyone can single-mindedly declare that a pile of clay is a sculpture, But that's uninteresting.

What's interesting is that when we work with clay, shapes begin to appear that we may find worth elaborating, and eventually our work has transformed the pile into a sculpture. In this sense, the clay is related to the sculpture by having properties that make it easy to shape. We can test shapes, revise them, and accumulate knowledge on how to proceed until we're satisfied with the result. The sculpture is related to the clay e.g. by having degrees of detail and textures that are possible to achieve with clay. -

Facts, the ideal illusion. What do the people on this forum think?Are you able to name a fact and if yes how do you know completely certain there is one? — Plex

It's s fact that these marks on this page are words. I know it for certain since I wrote some of them, they're published and open to read. -

The relationship of the statue to the clay

Ok, but my point is not that 'house' can have many definitions, but that the form of a house is insignificant for its definition.

A homeowner and a contractor can agree to build a house in the form of a pile of building materials as long as it can be used according to the building regulations (e.g. provide shelter, possibilities for cooking, toilet, shower etc).

There is no form shared by all houses. Instead, there are some functions shared by all houses. -

The relationship of the statue to the clayBut it is very difficult to find an example where forms are discovered, not created. — javi2541997

New forms and properties are discovered now and then. See for example aperiodic tiling. -

The relationship of the statue to the clayI am lucky enough to live in the house I remade for myself. So, both made and found. The 'made' is also a matter of finding in regard to what I could afford. — Paine

Interesting :up: I've recently built a house for myself too. The ground is remade, but the house is made from scratch. In the design and construction process you both make and find parts and their features relative to a whole.

Like drawing a picture, where there are too many details to draw, too many decisions to make, so you leave some parts blank/unbuilt until the drawn or built parts give you sufficient reason to complete the picture/building. -

The relationship of the statue to the clayA pile of building materials is not a house. — LuckyR

Some pile of building materials is possibly a house somewhere. An unfinished house can be a house. Lots of things that were not designed to be houses are houses, for example, caves, trees, cars, boats, old factories.

Other houses remain uninhabited when too expensive or when used as a financial investment.

Does it matter whether an object is designed by intent?

In an aleatoric process, forms are discovered, not created. Or they're "created" by being discovered and used in new ways. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsYou just quoted the OP out of context, — Bob Ross

No, I didn't do that either.

The biggest problem for indirect realists (that's the title of your OP) is their own assumption that we never experience objects and states of affairs directly. How is knowledge possible even under such conditions? Hence the complexity of Kant's investigation, and its seemingly paradoxical use of two worlds or perspectives. Such problems don't even arise for direct realists or idealists. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect Realistsyou didn't even attempt to address the OP at all. — Bob Ross

I'll quote the part of the OP again to which my first post is a response

..what grounds do we have to accept Kant’s presupposition (that our experience is representational)? — Bob Ross

Examples of illusions, dreams, hallucinations etc. ... — jkop

For many indirect realists, arguments from illusion, dreams etc. are "grounds" for accepting representational experience.

Kant is more sophisticated, but his presupposition (that objects are conformed by the categories and the perceptual apparatus) amounts to the conclusion that we never experience objects directly, only indirectly by way of experiencing conformed versions first. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsThe question is posed as if it is possible to compare the appearance and the object, implying that they are separable. I think that relies on an implicit 'world-picture' of the self and world - but that itself is a product of the brain/mind! We can't 'get outside' phenomena in that way. — Wayfarer

I agree we can't get outside phenomena. The question follows from concluding (from illusions etc) that we see external objects by way of seeing something else first (e.g. sense-data, mental representation etc). That's indirect realism. It creates an insurmountable gap between what we see and what it supposedly represents.

Idealism and naive realism are two ways of closing that gap, but Kant rejects both. His ontology consists of categories, not objects. Objects are conformed by the categories. It sure seems to assume that there are two objects, or two versions of one object: one we see, and another we don't see. -

The Biggest Problem for Indirect RealistsIf we don’t trust our conscious experience to tell us about the things-in-themselves to some extent, then what grounds do we have to accept Kant’s presupposition (that our experience is representational)? — Bob Ross

Examples of illusions, dreams, hallucinations etc. tend to make some thinkers conclude that the object of experience is not the external object but a figment of the perceptual apparatus, conceptual scheme, language, culture etc.

But if the object that we see is only our own phenomenal object, then how can we explain its relation to the external object?

We can't, and idealists know this, but "solve" the problem by rejecting the external. However, Kant's transcendental idealism maintains the external object by distinguishing between its empirical sense and transcendental sense.

In its empirical sense it's an object of experience, but in its transcendental sense it's an abstraction, an object without properties, hence imperceivable.

But it seems to make explanations of perceptual experience ambiguous, e.g. when we see the empirical object, do we see the object or our own phenomenal representation of... what? It also seems to make skepticism true, e.g. do we see the object, a representation, or an hallucination?. -

What can’t language express?Is there anything that language can’t express ? I don’t think it’s very good at expressing emotion because emotion is non-linguistic. — kindred

No, we use ordinary or poetic languages for expressing emotions. Often in combination with other ways of expression, e.g. gestures, sounds, and pictures.

Some ways of expression are recognizable as symbols for emotions, because they exemplify properties shared by what they express.

For example, "Ouch!" expresses sudden pain by exemplifying some property it shares with the experience (i.e. something sudden, uttered as if being hit or surprised etc.) It's a metaphorical exemplification that's frequently used in literature, theatre, music, pictures, cartoons etc. -

PerceptionI think 'naive' is fine, because in the philosophy of perception it does not refer to ignorance.

— jkop

What does it refer to then? — Metaphysician Undercover

Versions of direct perceptual realism (e.g. McDowell's disjunctivism, or Searle's non-disjunctivism).

Compare it with indirect perceptual realism, which is sometimes called 'scientific' despite the fact that it does not refer to science per se but the philosophical assumption that perception is indirect since scientists can manipulate the conditions of observation and evoke non-veridical experiences or hallucinations. But from artificially evoked experiences or hallucinations it doesn't follow that all experiences are hallucinations, nor that we never directly experience objects and states of affairs.

In both of these cases the words 'naive' and 'scientific' are used metaphorically (or rethorically), not literally. -

PerceptionI still like the term naive realism. I think it is apt since it's not doing justice to any adequate theory of realism. An adequate theory of realism would have to treat the perceiver as a genuine agent, not an entirely passive recipient of a purely objective world in all its glory. — Bodhy

Have you read any of the above mentioned philosophers on perception? Try this.

Hence, why I think critical realism and new realism are better positions since they're seeking a better understanding of what it even means for something to be real. — Bodhy

They're better, because they're better at satisfying what you already assume? :roll:

What are you saying, that "direct realism" is better terminology? — Metaphysician Undercover

No, 'direct' is equally misunderstood by uncharitable opponents. I think 'naive' is fine, because in the philosophy of perception it does not refer to ignorance. -

PerceptionThere is a reason why the word "naïve" is used to describe naïve realism. The person holding this view is like an ignorant child rejecting higher education. — Metaphysician Undercover

Like Aristotle? Putnam? Searle? McDowell? To ascribe child-like ignorance to those who defend naive realism is not so educated.

In the philosophy of perception, 'naive realism' is the name for the idea that the relation between observer and object is direct. -

PerceptionWhat matters is that both a) I see a can of red Coke and b) the photo does not emit 620-750nm light are true. — Michael

a) is false. You don't see red. One colour, or a bundle of colours, can look like another colour. For example, at dusk, dawn, under coloured lights, in pointilistic paintings, RGB screens etc.

the colours we see are determined by what the brain is doing. — Michael

That's also false. The blind can't see anything no matter what their brains are doing. -

PerceptionThe arguments from illusion continue to pile up, as if the hight of the pile would make them more convincing. :roll:

Did anyone mention RGB? The screens of modern phones, tablets, computers, TVs etc use three colour channels: red, green, blue. There's no yellow light emitted from these screens, yet they can depict yellow objects, and we see them as yellow. But the truth is that those are faint green colours looking as yellow.

Try this. Open a picture of a yellow colour swatch on your phone, zoom in so that the colour covers the entire screen. Then go into a dark room or closet, and let the light from the screen shine on a (white) wall. The light on the wall does not look so yellow. It's faint green. -

People Are LovelyDo you believe the balance between our focus on the positives and negatives has an optimal state or are we necessarily in various states of flux regarding how we regard others? — I like sushi

Our lives and communication with each other would become unnecessarily difficult or impossible if we'd focus on negatives only. In fact, it is irrational to focus on negatives when positive interpretations are available (this is basically the principle of charity).

To focus on negatives enables us to avoid negatives. To focus on positives enables us to enjoy positives. They're not mutually exclusive, so I'm not sure there's anything to balance here. Both are functions of our interest, both increase our fitness. -

The Problem of 'Free Will' and the Brain: Can We Change Our Own Thoughts and Behaviour?Can We Change Our Own Thoughts and Behaviour? — Jack Cummins

After you become aware of having a thought, you still have the capability to veto the thought, e.g. ignore it or think of something else.

You don't get to choose (homunculus) what thoughts pop up in your conscious awareness , but you do get to choose to withdraw, distract, focus, or redirect your awareness of thoughts, and change your behaviour accordingly. -

Communism's AppealWhy or how has communism lost its appeal, if it really has? — Shawn

It lost its appealing support for workers' rights, for instance, because many workers have become consumers, stock owners, home owners etc. It seems to me that today's communists don't mind being capitalists themselves. They have found other means for acquiring political power, e.g. by supporting minorities, implementing identity politics etc. -

Stoicism & Aesthetics..art became an off-shoot from crafts, like philosophy became an off-shoot from science.

— jkop

I think you have gotten that backwards ;) — I like sushi

Well, philosophy used to be the name for science, recall. The off-shoots from this old sense of science are the special sciences and philosophy in their modern senses. Likewise, the modern sense of 'art' is an off-shoot from an older and more inclusive sense of crafts.

they may well not have had a specific word for Art but certainly had enough terms to talk of it how we do. — I like sushi

They could, but modern art, especially concept art, is often context-dependent, whereas the meanings of craft manifest in the works. -

Stoicism & AestheticsI thought this might be of interest.

— T ClarkThe Greeks and Romans had no conception of what we call art as something different from craft; what we call art they regarded merely as a group of crafts... — R.G. Collingwood - The Principles of Art

Right, art became an off-shoot from crafts, like philosophy became an off-shoot from science.

Some contemporary art is craft-like, and some contemporary philosophy is practiced scientifically. But there's a lot of art without craft (replaced by concepts, originality, fame etc), and there's a lot of philosophy practiced like literature (some being critical or hostile to science).

What might the ancient stoics say about modern concept art? A modern stoic? -

PerceptionIf there is no color in the world, then rainbows and visible spectrums are colorless. — creativesoul

:up: :100: -

Stoicism & AestheticsIt's a synthesis of sense and intellect. We look, see, feel and judge works of art or nature, no matter whether they are ugly or beautiful. — Amity

Right, so perhaps a stoic finds meaning in the understanding of works of art, whereas a hedonist finds meaning in being attracted, surprised, provoked etc by works of art. Therefore, it might matter for the hedonist whether a work is ugly or beautiful or at least interesting. -

PerceptionYou could hardly be recognized as biased if your expressions were meaningless. — frank

One does not even have to speak. They have already diagnosed whatever one says as a function of identity, sexual phobias, privileges, self interest, inherited sin etc. Thus any criticism can be dismissed as biased, regardless of the truth of the words. -

PerceptionThat brings up the issue of understanding the biases of those who step back from science

— wonderer1

Yes. That's also part of phil of sci. — frank

Makes me think of the many revelatory ideologies (freudian, marxist, individualist, religious etc), categorically assuming underlying biases, power relations etc. no matter what. They just "know' that what one says or writes is a function of one's biases, not of the meanings of the words. -

Perception

-

PerceptionI think the term you're looking for is "fluorescent", — Michael

No, I'm not looking for a term, and plaster walls are not fluorescent.. -

PerceptionNot sure what you mean by "pigments" here, but it's usually things like stars and torches and lightbulbs and fire that emit photons. — Michael

I'm not talking about stars, torches, nor lightbulbs. but pigments. Pigmented surfaces exposed to light emit light, unlike glossy surfaces that reflect light.

A pigmented surface is uneven, incoming photons bounce and scatter on it according to the wave-like behaviour of light. That's why a rough plastered wall, for instance, emits/spreads more light on its surroundings than a smooth glossy wall which instead reflects incoming light.

Walls of plaster, wood, stone etc may both emit and reflect light in various degrees, but that's because their pigmented surfaces (which emit light in the above sense) can be grinded or treated or covered with glossy materials (reflecting light). -

PerceptionThe rejection of naive realism is like obscurantism: a habit among intellectuals to expect a phenomena or its explanation to be sufficiently complicated to appear advanced, learned, intriguing, surprising, absurd, or incomprehensible even... anything but mundane or naive. If the explanation is too obvious, then it won't be taken seriously.

Yet I don't know of any good arguments against nsive realism, so perhaps it's worth investigating (but in a separate thread) :cool: -

PerceptionSo we have an superficially enigmatic situation in which the ball does not change colour but the colour changed. Is this a paradox? Not at all. We understand the background of each description, and we acknowledge the truth of both: this is what a red ball in part shade looks like. — Banno

Right, in white light that has the energy of daylight the pigments emit photons of about 700 nm. In shade (ambient light) they emit photons with less energy. Hence the red is darker or less saturated in the shade.

A damaged eye, brain injury, spectral inversion, colour blindness, hallucination, illusion etc. may impair one's ability to see things as they are, but an impaired ability won't change what there is to see: a coloured world of pigments, shapes, varying behaviour of light. -

PerceptionThe percept of the ball changed, but its color stayed the same. — Leontiskos

No, the change is the shadow falling over a part of the red ball, making that part look dark red. That's what there is to see.

The "percept" (or mental phenomenon) is the seeing, not the colour that one sees. Even if the colour is a systematic hallucination, it is not a percept. What makes it systematic is the fact that the hallucination is causally constrained by the eye's interaction with wavelength components of light. -

PerceptionI don't have a copy of Searle, but according to this:

Searle presents the example of the color red: for an object to be red, it must be capable of causing subjective experiences of red. At the same time, a person with spectrum inversion might see this object as green, and so unless there is one objectively correct way of seeing (which is largely in doubt), then the object is also green in the sense that it is capable, in certain cases, of causing a perceiver to experience a green object.

This seems to be arguing that colours are mental phenomena, and that the predicate "is red" is used to describe objects which cause red mental phenomena. — Michael

:roll: According to Searle, colours are systematic hallucinations, and what characterizes hallucinations is that you're having experiences without experiencing anything, not even percepts. -

The Sciences Vs The Humanities"Every effect has a cause" may be true, in a way. But it does not follow that every effect must have a cause which is a specific component of the building. The cause of utility might be an effect of the totality of the building as built, rather than as a collection of components. — Ludwig V

No, its utility may become available when it's built, but just being available does not cause anything, unless it already has the property, which can attract and initiate use.

Short version - holistic aspects of the building. — Ludwig V

Here's a sketch of different levels of composition that I'm thinking of:

Architecture is a composition of practical, beautiful, sustainable parts.

The practical, beautiful, sustainable parts of architecture are composed of materials, structures, processes.

The materials, structures, processes are composed of minerals, organic or other chemical compounds, geometries, structural design, causal chains, relations to contexts etc.

jkop

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum