Comments

-

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Lol, Biden just showed again why the Democrats sidelined him (or the people who sponsor the party). Yet how could he remember the classic gaffe made by Hillary Clinton?Trump capitalizes on Biden calling his supporters garbage. — NOS4A2

Best way to get people to vote for Trump. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Lol.It's obvious that the US/NATO insistence on a military rather than a diplomatic solution is a guarantee for Ukraine's eventual collapse. — Tzeentch

As if there would be a "diplomatic solution" for the artificial state that ought to be part of Russia (or at least parts that are Novorossiya) and is ruled by nazis.

But coming back to the thread.

European green parties are demanding that Jill Stein would not run, because it favors Trump.

First, it's none of their business and second, this is the utter stupidity that continues the stranglehold of the two dominant parties in US politics (which is one cause of the stagnation and corruption).

Also shows just how much "comradeship" there's in the green ideology. -

How does knowledge and education shape our identity?In my view Wittgenstein's comment of "Psychology is no nearer related to philosophy, than is any other natural science" just refutes the idea that philosophy would be psychology. At Wittgenstein's time psychology was quite new, actually.

Today psychology is understood as an interdisciplinary field of study and close to sociology, not purely a "natural science".

Just like there's a difference between data and information, I think there's also a difference between "memory" or memorizing something and the knowledge (and the understanding) of something. And this understanding defines how we act, how we view the World and things in it, which surely then passes on to the distinguishing character or personality that we have.Apart from education as a formative process in the young mind, I would like to ask the reader about how does the reader suppose that knowledge can influence one's identity? My personal belief is that knowledge is a form of "memory" encoded in the brain, more specifically the hippocampus. — Shawn -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Really??? :yikes:Pulling the rug on the Ukrainians wouldn't weaken NATO. It would strengthen it. — Tzeentch

Oh I get. Just like Trump threatening to take out the US ground forces out of Europe would strengthen NATO...because European countries should then really commit to their defense. Or something like delusional like that.

This is really crazy, really. Somehow you seem not to understand that it's an European objective to not let Russia defeat and conquer Ukraine (or take the parts it wants and put a "denazified" puppet regime in the carcass state that is left). How cannot you fathom this? NATO members simply would be worse of if Russia wins the war. The Baltic States would be worse. Finland and Sweden would be worse off. Something as totally evident like this comes somehow to be blurred in this anti-Americanism. Or Trumpism, for that matter. That Trump gave Afghanistan on a platter to the Taleban seems not to matter at all.What's weakening NATO is the fact that we're trying to drag Ukraine in even though it would lead to endless conflict with the Russians, undermining the security of everyone involved. — Tzeentch

Russia wants to destroy the link between the US and Europe. Russia is against the European Union. Somehow you don't see this reality.

This is really the deafeatism that causes the West to lose it wars and emboldens Russia to annex territories from it's neighbors (which apparently you don't care about). The selectivity of anti-Americans is just incredible: somehow they can be against Israel's actions, but when it comes to Russia doing similar annexations it's OK, reasonable, realpolitik... and it's basically the fault of the US. Countries simply can do some things right and some things wrong.

And this is the cause of this delusional thinking. The sheer hubris to think everything evolves around the US and that everything happening in the World because of the West is the real problem here. This creates the World where the West loses. Because for you the US is the reason for all the troubles in the World. And other countries don't matter... especially if they agree on something with the US.And yea, Ukraine is hardly the first disaster Washington has created, but that's their problem. — Tzeentch

What United States has done has also actually has helped. I would prefer a South Korea to exist rather have it to be a part of North Korea. Yes, I'm fully aware that South Korea wasn't a democracy until the late 1980's, but it's still totally something else than North Korea. Something else that should be helped to survive if attacked. In the same fashion was the correct thing for the US to oppose such thing as Soviet Union taking over Eastern Europe. And Ukrainians have the right to their country, it's not an artificial country that ought to be part of Russia and isn't ruled by nazis. Supporting their struggle is the correct thing.

Yet somehow being critical at US foreign policy becomes this incoherent crazy anti-americanism where the perpetrators and aggressors like Russia become victims of evil US. Poor, poor Russia.

Of course this is the election thread and even if this is an important factor in US foreign policy, it isn't important to the Americans who vote. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”From the OP:

. It seems that people sometimes either forget that something cannot exist prior to its conception, or can reason with a distorted vision of time, leading them to enter a reasoning of how something was created as if it did not already exist and was not used throughout the reasoning. As if things could exist and not exist at the same time.

It's kind of like the liar paradox “this sentence is false” that implies the attribution of a truth value before the sentence is created, which creates some kind of weird time distortion where future and past events get mixed up and circle back to each other because they are contradictive.

"This sentence" refers to a future reference which is "this sentence is false". So it's attributing a truth value to itself that is not constructed yet. And the analysis after the creation contradicts the analysis based on events that did not happen yet so it's continuously changed — Skalidris

First, isn't being conscious subjective?

At least I assume that somebody that is conscious is a subject: he or she or it can think and act on it's own choosing. The acting is not a simple mechanism like throwing a burning matchstick in a pool of gasoline and the liquid blowing up. And Philosophers like Chalmers and Searle hold that consciousness is necessarily subjective or first person in character and that subjectivity is an ontological feature of consciousness. So at least here I'm not way off.

But let's think about this.

If subjectivity is an ontological feature of consciousness, can we then really accurately model consciousness with a conventional model, that is objective?

Let me try to explain what I'm after here: If we try to model consciousness objectively, the rules of objectivity come immediately into consideration and we have a logical problem in modelling this subjectivity. We usually end up with some kind of a black-box model: something is happening in our "black box", in our brains, and somehow, out comes consciousness. In the black box happens something, what could be said to be our consciousness.

And then we start to compartmentalize just where is this "black box" and how it works... usually in a similar fashion that we model some engine, computer or network. Yet we are still looking at all of this objectively from the outside, think that the logic here is equivalent to some simple mechanical or chemical reaction that a scientist can easily do in the lab. Especially as something that you can give a computable model.

The logic of the subjective is likely different from this. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

The worst thing for him is to pull out the rug from the Ukrainians and weaken NATO while getting more entangled in the Gaza genocide and with the war with Iran in the Middle East. And yes, he can do both, even if it's not the likeliest outcome.Trump would be better for Europe. The worst thing he can do is pressure European countries to pay for their own security, which we ought to be doing anyway. — Tzeentch

Let's remember that he has done already a huge Dolchstoss to one allied nation, that collapsed immediately and he did it without even negotiating with his allies. I bet that Kim il Sung would have immediately jumped to a peace offer during the Korean war if Trump would have been there to give a surrender paper like he gave to the Taliban. Yeah, I bet that Kim Il Sung would have promised not to attack mainland US and then squashed with Chinese support the back stabbed South Koreans. Then no Korean electronics or K-pop, just larger famines in the Korean peninsula.

But naturally nobody talks about Afghanistan, the longest war the US fought, because both parties have played a role in that disaster. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

The truth is that the UN can perform only a limited things well. It can be between two sides, when both sides accept this. But it's laughable to think the UN could act like a superpower. Really, the Korean war fought under the UN flag happened only because China was represented by the nation now known as Taiwan and the Soviets had foolishly boycotted the Security Council and wasn't there to veto the thing.The UN sat by for years while Hezbollah constructed terror installations when it was in the UN's deliberate mission to disarm them. — BitconnectCarlos

The idea that the UN could "disarm" Hezbollah is ludicrous. If the IDF with all it's might couldn't disarm Hezbollah while occupying Lebanon last time, how could a small contingent of a battalion size or so lightly armed blue berets do that?

But I guess that was this kind of agreement that all sides could OK in the Security Council, while knowing it wouldn't happen. Many actions are hypocritical. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

The US politicians are just in the pocket of the Israel lobby thanks to mainly the Pro-Israeli Christians in the electorate, not just the American Jewish community. It's quite obvious that the US doesn't want the kind of "final solution" which the Netanyahu government hopes it can do somehow. These things take a lot of time to change, but I think they are changing.I think the better explanation is that Israel / US simply have no practical way to defeat Iran.

They've been in a delusional driven genocide with constant escalation to try to distract from the Genocide internationally (new enemies to continue to be the victim) and also maintain credibility domestically of being the superior race that can go around killing all their enemies. — boethius

But do notice that you have two different administrations and states here.

I have to agree with you. Those missiles hitting Nevatim Air base really were hitting Nevatim air base. And the US is in no position to occupy Iran.The spell of invincibility broke between due to Iran's missile attack demonstrating Israeli air defence doesn't work so well (so Iran can cause significant damage conventionally) and also the pentagon simply having no plan to actually defeat Iran (Israel overconfidence likely includes overconfidence in US capacity as well). — boethius

Nuclear weapons hinder the pace of going up the escalatory ladder, but they don't keep states from fighting each other ...as long as the fighting is "limited" in scale. Argentina could attack easily the UK as there really was no threat of a nuclear mushroom cloud engulfing Buenos Aires. The UK wouldn't use nukes to defend few inhabitants and sheep in the Falklands. Also Pakistan and India could have a border war even with nuclear arms on both sides. And North and South Korea can engage in firefights then and now.

Hence the unfortunate reality is that it would be logical now for Iran to get it's nuclear weapon. The US will attack only nations that have potential nuclear weapons, but not a large and dispersed nuclear deterrent. That's why it's totally possible that Iran does have few nukes already. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Yeah, Trump will probably win. :meh:Most of us seem to agree Trump is winning as things stand, me, Mikie, the betting markets, Nate SIlver etc. — Baden

Hopefully I'm wrong.

And it's likely going to be worse than last time, because now he can demand to be surrounded by yes-men. Not like he will take a lot of generals into his cabinet, which naturally don't veer off from US policy where it has been on since WW2. He'll bring on people that he took on the last years of his prior administration.

Lame duck president for four years? -

Where is AI heading?

Yet the issue here is that they have to have in their program instructions how to learn, how even to rewrite the algorithms they are following. And that's the problem with the order for a computer "do something else". It has to have instructions just what to do.There are levels of 'controlled by'. I mean, in one sense, most machines still run code written by humans, similar to how our brains are effectively machines with all these physical connections between primitive and reasonably understood primitives. In another sense, machines are being programmed to learn, and what they learn and how that knowledge is applied is not in the control of the programmers, so both us and the machine do things unanticipated. How they've evolved seems to have little to do with this basic layered control mechanism. — noAxioms

A computer cannot be given such an order! Simple as that.A decent AI would not be ordered to do something else. — noAxioms

An algorithm is an mathematical object and has a mathematical definition, not a loose general definition that something happens. A computer computes. So I'm not rejecting the possible existence of conscious AI in the future, I am just pointing at this problem in computation, following arithmetic or logical operations in a sequence, hence using algorithms. I'm sure that we are going to have difficulties in knowing just what is AI and what is a human (the famous Turing Test), but that can be done by existing technology already.I don't think you understood how I explained algorithms. — Christoffer

This problem doesn't go away by saying that well, as we are conscious, hence there's those "algorithms" making us conscious. That's not the issue, the issue there's simply the difference in following orders and then us thinking of the orders and then making our decision. Modelling this just like an normal computer goes works isn't accurate. It comes basically close to the hard problem of consciousness, but this actually is about the limitations of Turing Machines that Turing in his famous article stated.

The Church-Turing Thesis asserts that any function that can be computed by an algorithm can be computed by a Turing machine. Turing himself showed that there are limitations on what a Turing machine can do, which basically is a result of negative self reference, when you think about it. In a way you could state the problem of subjectivity, which is crucial for consciousness. All that I'm saying is that computation isn't going to solve this riddle, it indeed can be something emerging from mimicking and plagiarization, but not just from simple algorithms that a computer goes through.

As I said, the World can be deterministic, but that doesn't mean that we don't have free will. The limits in what is computable is real logical problem. Or otherwise you would then have to believe in Laplacian determinism, if we just had all the data and knowledge about the World. Yet Laplacian determinism's error isn't that don't have all the data, it's simply that we are part of the universe and cannot look at it from outside objectively, when our actions influence the outcome.No, we do not have free will. The properties of our universe and the non-deterministic properties of quantum mechanics do not change the operation of our consciousness. Even random pulls of quantum randomness within our brains are not enough to affect our deterministic choices. — Christoffer -

There is only one mathematical object

This is a very interesting paper on the subject. Thank you, @Count Timothy von Icarus! :grin: :up:Barry Mazur has a really neat paper on this question, and at least parts of it are quite accessible. He ends up advocating (maybe just "showing the benefits of" is a better term) of an approach grounded in category theory. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Too bad that the basics of category theory aren't taught in school. But then again, the educational system doesn't care much about the philosophy of mathematics or the foundations of mathematics. -

Where is AI heading?

Just like with alchemy, people could forge metals well and make tools, weapons and armour, but we aren't reading those antique or medieval scriptures from alchemy to get any actually insights today. Yes, you can have the attitude of an engineer who is totally satisfied if the contraption made simply works. It works, so who cares how it works.It's important, but not needed for creating a superintelligence. We might only need to put the initial state in place and run the operation, observing the superintelligence evolve through the system without us understanding exactly why it happens or how it happens. — Christoffer

Well, this is an site for philosophy, so people aren't satisfied if you just throw various things together and have no idea just why it works. You can be as far away as the alchemists were with the idea of transforming "base metals" into "noble metals", like gold. Well, today we can produce gold in a particle accelerator, our best way today to mimic a supernova nucleosynthesis, which actually forms the element. Just how off ideas of alchemy were from this is quite telling. Still, they could Damascus steel.

What other way could consciousness become to exist than from emergence? I think our logical system here is one problem as we start from a definition and duality of "being conscious" and "unconscious". There's no reasoning just why something as consciousness could or should be defined in a simple on/off way. Then also materialism still has a stranglehold in the way we think about existence, hence it's very difficult for us to model consciousness. If we just think of the World as particles in movement, not easy to go from that to a scientific theory and an accurate model of consciousness.As per other arguments I've made in philosophies of consciousness, I'm leaning towards emergence theories the most. That advanced features and events are consequences of chaotic processes forming emergent complexities. Why they happen is yet fully understood, but we see these behaviors everywhere in nature and physics. — Christoffer

I think our (present) view of mathematics is the real problem: we focus on the computable. Yet not everything in mathematics is computable. This limited view is in my view best seen that we start as the basis for everything from the natural numbers, a number system. Thus immediately we have the problem with infinity (and the infinitely small). Hence we take infinity as an axiom and declare Cauchy sequences as the solution to our philosophical problems. Math is likely far more than this.I'm leaning towards the latter since the mathematical principles in physics, constants like the cosmological constant and things like the golden ratio seem to provide a certain tipping point for emergent behaviors to occur. — Christoffer

But the machines we've built haven't emerged as living organisms have, even if they are made from materials from nature. A notable difference.Everything is nature. Everything operates under physical laws. — Christoffer

A big if. That if can be still an "if" like for the alchemists with their attempts to make gold, which comes down basically to mimicking that supernova nucleosynthesis (that would be less costly than conventional mining or the mining bottom of the sea or asteroids etc).If we were able to mechanically replicate the exact operation of every physical part of our brain, mind and chemistry, did we create a machine or is it indistinguishable from the real organic thing? — Christoffer

Exactly. It cannot do anything outside the basics of operation, as you put it. That's the problem. An entity understanding and conscious of it's operating rules, can do something else. A Turing Machine (a computer, that is) following algorithms cannot do this.The algorithms need to form the basics of operation, not the direction of movement. — Christoffer

You're not using here the term "algorithm" incorrectly or at least differently than me here.A balanced person, in that physical regard, will operate within the boundaries of these "algorithms" of programming we all have. — Christoffer

Algorithm is a is a finite sequence of mathematically rigorous instructions, typically used to solve a class of specific problems or to perform a computation. We might be built by the instructions in our DNA, but don't use our DNA to to think or to put it another way, there's far more to us having this discussion than just the code in our DNA. As we are conscious, we can reason just why we have made the choices that we've made. That's the issue here.

We do have free will. Laplacian determinism is logically false. We are part of the universe the hence idea of Laplacian determinism is wrong even if the universe is deterministic and Einstein's model of a block universe is correct.We are still able to operate with an illusion of free will within these boundaries. — Christoffer -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankSo now Israel hit Iran by going after it's air defense. But not the nuclear sites and, of course, not yet the oil installations, which would bounce oil prices higher. Seems like Bibi listened to the US administration and now waits just how the US elections are going to go.

If Trump get's into office, will then the nuclear sites be targeted? -

Perception of Non-existent objects

How would we perceive them?Could there be other factors involved in perception apart from the the object of perception, sensory organs, memories and experiences? — Corvus -

Where is AI heading?

Oh yes, many times scientists stumble into something new. And obviously we can use trial and error to get things to work and many times we can be still be confused just why it works. Yet this surely this isn't the standard way of approach, and especially not the way we explain to ourselves how things work. This explanation matters.But we invent things all the time that utilize properties of physics that we're not yet fully able to explain. — Christoffer

Yet understanding why something works is crucial. And many times even our understanding can be false, something which modern science humbly and smartly accepts by only talking of scientific theories, not scientific laws. We being wrong about major underlying issues doesn't naturally prevent us innovative use of something.To say that we can only create something that is on par with the limits of our knowledge and thinking is not true. — Christoffer

Just look how long people believed fire being one of the basic elements, not a chemical reaction, combustion. How long have we've been able to create fire before modern chemistry? A long time. In fact, our understanding has changed so much that we've even made the separation between our modern knowledge, chemistry, from the preceding endeavor, alchemy.

Now when we have difficulties in explaining something, disagreements just what the crucial terms mean, we obviously have still more to understand that we know. When things like intelligence, consciousness or even learning are so difficult, it's obvious that there's a lot more to discover. Yet to tell just why a combustion engine works is easy and we'll not get entangled into philosophical debates. Not as easily, at least.

In a similar way we could describe us human being mechanical machines as Anthropic mechanism defines us. That too works in many cases, actually. But we can see the obvious differences with us and mechanical machines. We even separate the digital machines that process data are different from mechanical machines. But it was all too natural in the 17th Century to use that insight of the present physics to describe things from the starting point of a clockwork universe.So, in essence, it might be that we are not at all that different from how these AI models operate. — Christoffer

I agree, if I understand you correctly. That's the problem and it's basically a philosophical problem of mathematics in my view.if we're to create a truly human-like intelligence, it would need to be able to change itself on the fly and move away from pre-established algorithm-boundraries and locked training data foundations as well as getting a stream of reality-verified sensory data to ground them. — Christoffer

When you just follow algorithms, you cannot create something new which isn't linked to the algorithms that you follow. What is lacking is the innovative response: first to understand that here's my algorithms, they seem not to be working so well, so I'll try something new is in my view the problem. You cannot program a computer to "do something else", it has to have guidelines/an algorithm just how to act to when ordered to "do something else". -

Where is AI heading?To reach this point, however, I believe those calculations must somehow emerge from complexity, similar to how it has emerged in our brains. — Carlo Roosen

I think the major problem is that our understanding is limited to the machines that we can create and the logic that we use when creating things like neural networks etc. However we assume our computers/programs are learning and not acting anymore as "ordinary computers", in the end it's controlled by program/algorithm. Living organisms haven't evolved in the same way as our machines.Yes, my challenge is that currently everybody sticks to one type of architecture: a neural net surrounded by human-written code, forcing that neural net to find answers in line with our worldview. Nobody has even time to look at alternatives. Or rather, it takes a free view on the matter to see that an alternative is possible. I hope to find a few open minds here on the forum.

And yes, I admit it is a leap of faith. — Carlo Roosen

I think the real problematic hurdle that we have is philosophical. And surely this issue isn't straightforward or clear to us. -

Perception of Non-existent objectsI think that one thing would be obvious in the realism of dreams. If you don't have any idea or experience of something, you likely won't have that in your dream either.

So likely when in your dream flying a light airplane of the night sea, I assume that it's likely you flew it straight and level. It's likely that didn't stall the airplane and put it into a tailspin or perform high-G turns or inverted flight.

Having flown sailplanes, done even aerobatics with them and few times been at the controls of motor airplanes, it's the motions that you experience that cannot be duplicated by the smart simulators of today, even if Microsoft Flight Simulator mimics reality very well otherwise. These motions are very mild in passenger aircraft, that nearly everyone has flown in: the acceleration at take off and the tiny effect of turbulence. Yet few have experienced how being in a tailspin feels like or how G-forces are experienced in the air. A roller coaster ride gives some feel of this, but as a roller coaster ride is done on rails, it misses just how smooth aircraft feel as they're not attached to rails.

How that then comes in your dreams is interesting, as usually we see, hear, touch and can even smell something in our dreams, but the inner ear's vestibular system isn't giving us much feedback, especially not something that we haven't experienced. Yet if you have a lot of experience of something, you likely can feel experiencing it in your dream too. -

There is only one mathematical object

Ok, I perhaps I could have better defined the axiom of choice, but in the latter you get the point.You're conflating non-equivalent theorems. — TonesInDeepFreeze

That basically was my question. And I think comes to this thread's main question, because mathematics is quite connected.This brings up an interesting question: If two things are equivalent, A<->B, does that mean they represent the same math object? — jgill

Perhaps our questions define what we treat as objects. Could logical mathematics in it's entirety be an object compared to let's say something different like poetry. -

The News DiscussionHi javi,

Yep, even the Finnish media noticed this. But we can agree that there's countries with even worse public health sectors. But it's the general malaise in Europe, the debt-lead economic system will have huge problems with low growth, demands for the health care sector increasing and government incomes decreasing.

The fact that both in Spain and Finland there will be far more less children in the future doesn't make me more hopeful that things will get better. Even with the health care of children. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

I think it's quite obvious that where UNIFIL has stations and observation posts is known to everybody and in the maps. Let's take for example just some of the attacks at UNIFIL troops by the IDF:I am curious about that. I think 5 were injured last time I checked. Perhaps a mistake? Fog of war? I don't know. I'd be horrified if Israel viewed the blue berets as valid targets alongside Hezbollah. — BitconnectCarlos

(October 10th, POLITICO) ROME — Two United Nations peacekeepers were hospitalized after an Israeli tank fired at an observation tower Thursday, according to the U.N. mission in southern Lebanon.

The U.N. peacekeeping mission UNIFIL has been operating along the “Blue Line” that separates Lebanon and Israel since the 1970s, with a mandate to restore security in the area. - The U.N. said in a statement that Israeli forces have "repeatedly hit" its positions in recent days, including two Italian bases and the mission headquarters in Naqoura, a coastal town in the southwest of Lebanon.

And then, six days later:

(Oct 16th, Al Jazeera) UN peacekeepers in southern Lebanon say Israeli forces have fired at one of their positions in the south in a “direct and apparently deliberate” attack that damaged a watchtower.

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) said on Wednesday its peacekeepers near southern Lebanon’s Kfar Kila observed an Israeli Merkava tank “firing at their watchtower”, adding that “two cameras were destroyed, and the tower was damaged”.

You really think that a Merkava tanks, with their superb optics and fire control just "accidentally" fire on a marked and known UN watchtower? Fog of war, really? I won't buy the idea that tank crews are so disobedient and reckless that they just themselves decided to fire upon UN installations when they felt like it.

Look, Israel simply tries to intimidate UN forces simply to leave, hence there then would be nobody observing what they do. It's the obvious fact here. Even if nobody listens to what UN says, it's still there as an annoying neutral observer. Besides, there's historical examples of this. In one case in a prior war (if I remember correctly in the Golan Heights) IDF soldiers wanted UN peacekeepers that were Finns to abandon their observation post, which the Finnish blue berets refused to do. As the situation with two armed sides pointing assault rifles at each other was dangerous, the Finns laid down their weapons, but still refused to move. Hence an Israel-Finland wrestling match ensued. -

There is only one mathematical object

Let's try an example to clarify this idea:Yes, the similarities don't define the object, however. Is an "object" its' representation picked at random? Or, is there a more metaphysical meaning of the one object having representations? Is there an Object Theory? Just thinking of a way this thread might proceed. — jgill

What would be the mathematical object behind/described by the "well ordering theorem", which can be described as every nonempty set of positive integers contains a smallest member?

How is this object comparable to the axiom of choice? They are basically equivalent to each other. Are they still two different mathematical objects? Do they differ and if they do, how?

Thoughts? -

There is only one mathematical objectI think the one issue in mathematics is that defining a "mathematical object" can be difficult if there are equivalencies, multiple ways of representation of the "object". There's a whole field of mathematics just looking at these similarities, category theory.

-

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankWhat seems not to have been discussed is the possible nuclear weapons test made by Iran.

If the earthquake in a region where a testing site is would have been a nuclear explosion, although it could have been also eathquake (as there are earthquakes in Iran). Yet if it was, the absolute silence in Israel (except the Jerusalem Post) and in the US would be totally in line with how historically the US (and the West) reactions of the past.

When North Korea made it's first nuclear experiment and the tremors were noticed in an area where there's no earthquakes usually, the reaction was to play down it was a possibly a conventional explosion or in any case a failed test. And latter nuclear tests haven't made any outcry. With silence the North Korean nuclear arsenal has been building up.

Naturally this is speculation, but if Iran did make a nuclear test, it will be now frantically building it's meager nuclear deterrent and decentralized the weapon systems. As Iran and Israel are basically at war with each other (even if both sides really don't want to look it that way), then this would be the logical time for Iran to go through with it's nuclear weapons program. Anymore the "ability to make a bomb" isn't credible deterrence for Iran. And the rockets of Hezbollah aren't either, as Netanyahu has opted to destroy Hezbollah and invade Lebanon.

So that would leave Iranians with the attempt to have some kind of nuclear balance with Israel. Naturally this means that Saudi-Arabia or UAE could also decide to have nuclear weapons, if Iran goes public with it's nuclear deterrence. Yet also if Iran has a nuclear deterrent, even small one, it can also get a more aggressive. Which actually it has by now twice attacking Israel. Which in the latter strike the attack has seemed to have gone through... even if naturally the IDF says that the attacks were inneffective.

And Hezbollah (Iran) attacking Bibi's home with a drone in Ceasarea won't likely defuse the situation...

(Times of Israel) The Prime Minister’s Office confirms that the premier’s private residence in Caesarea was targeted in a drone attack from Lebanon earlier this morning.

In a short statement, the PMO says that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his wife Sara were not home at the time of the attack and that there were no injuries in the incident. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Formation of the Hezbollah was the result of the last occupation of Lebanon. That in itself shows how obvious this is.What the Israelis don't seem to understand is that it goes both ways. How many Oct 7s have happened to the people in Gaza and now Lebanon and how many civilians have been radicalized as a result? — Mr Bee

In an intelligent debate this would be obvious, but policy has been hijacked by ideology and propaganda, where the leaders themselves are believing their own propaganda. Bibi and his administration has morphed into a wartime cabinet. Now before Israel and the IDF made limited military strikes, but those did go hand in hand with foreign policy and basically were peace-time operations. Now once the military has been totally mobilized (and demobilized partly for the economy not to tank totally), the threshold of military actions has severely been reduced. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Whether UNIFIL is successful or not isn't the question here. It's attacking UN blueberets. It's just shows how absolutely reckless Netanyahu has come.UNIFIL needs to leave. — BitconnectCarlos -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankWell, Israel banned the UN general secretary.

Since you will have the backing of the US (Biden sent just more US soldiers to protect Israel and deployed there the THAAD system), why care? You can do anything you want, so now is the time to do that anything.

Never underestimate the impact how a large terrorist attack can be put to use to rouse people to support war.

And anyway, both this thread and the Ukraine thread were put into the "lounge", because they didn't fit to the main page. Wouldn't that be telling too? :wink: -

Climate change denial

Ummm....have you noticed that it's colder when the sun isn't up?Where is your evidence for this? Have you just made up this claim because you want it to be true? I have done a lot of researching about this and the biggest problem is that they don't specify the time of day that the maximum temperature occurs. So you can't tell if the maximum temperature happened during the day or during the night. Can you prove otherwise? — Agree-to-Disagree

Especially in the desert it's so. And when the highest temperature recorded temperatures are 54 Celsius or so, then it's quite reasonable to assume that the highest records are taken DURING DAYTIME.

But you aren't talking total rubbish. Night time temperatures have measured near 50 Celsius:

See Death Valley may have just had the hottest recorded midnight ever(New Scientist, 2023) Between 12am and 1am on 17 July, a weather station in Death Valley, California measured temperatures of 48.9°C (120°F). If confirmed it would be the hottest recorded temperature at that time

So @unenlightened is right. But a record to be close is still a long way from Kuwait having regularly +50 Celsius nights.

(Death Valley National park, picture from National Park Service)

But if you're living up to your name, then I can understand. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankI think it's quite reprehensible for IDF to attack UN peacekeepers. A Finnish officer that I know who was in Lebanon in UNIFIL just last spring commented that it was a miracle that nobody died there. Well, now UN blueberets have been killed or wounded. Well, now the

See hereIsraeli forces fired on the headquarters of the UN peacekeeping force in southern Lebanon for the second time in two days on Friday, injuring four peacekeepers.

Even the US noticed this:

US President Joe Biden has said he is "absolutely, positively" urging Israel to stop firing at UN peacekeepers during its conflict with Hezbollah in Lebanon, following two incidents in 48 hours.

At least in the Finnish newspapers an security analyst told the reality how it is, because lets face it, UNIFIL has been in Lebanon since 1978 and to for a tank to fire on UN base (HQ) is no accident: Israel is trying to get the UNIFIL troops to be withdrawn so that IDF can create a new security parameter in Southern Lebanon. And although there was one before and it didn't work so well, who cares. Netanyahu is on the roll.

And on what the future holds for Gaza, here's an interesting possibility what Bibi has in mind now:

The Open air prison is divided to many open air prisons to handle the prison riot. -

There is only one mathematical objectThank you for the response. I don't think we have any real disagreement here and I think you got my point.

Well, that article basically states what this is about: attempt to get job positions. What better way is there to accuse a field of study, mathematics, to itself be "white and patriachial", or whatever. But it works. What can the head of a mathematics department say when accused that there are too few if any women or minorities represented in the staff? Stop hiring your male buddies and follow the implemented DEI rules!How bad has it gotten when Scientific American, of all outlets, publishes Modern Mathematics Confronts Its White, Patriarchal Past. — fishfry

With this short interlude to social discourse, I would like to go back to the actual topic of this thread. -

Scarcity of cryptocurrencies

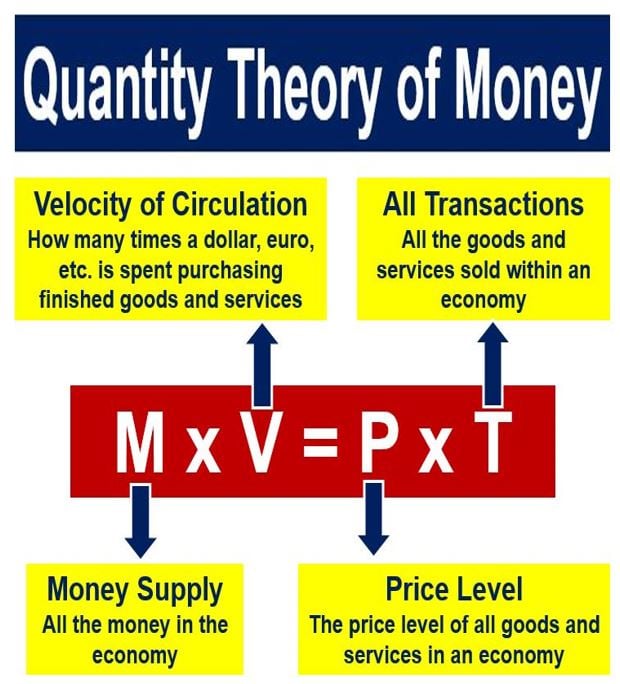

Good that you agree with the Fischer equation. Yet it's actually very important to understand it, because the increase in the money supply doesn't automatically mean that it's value goes down. For example when a speculative bubble bursts creating a banking crisis, the velocity of circulation tanks. Banks won't be lending anymore, but will sit on their money like Scrooge McDuck. Hence if the Central Bank prints more money or in the Nordic model, creates a "bad bank" where all the toxic garbage loans are parked, this doesn't create inflation.And yet in the quantity theory of money graphic you posted, both scarcity (money supply) and velocity determine price. I agree with the graphic. — hypericin

This is a policy decision. If you just bail out the people that where carelessly creating the bubble at the first place, then the game will just continue. If you let large banks go bust or put away to jail the most reckless bankers, that sends a totally different message.This increase in supply does not sit stagnant like you suggest. It is invested in the stock market, in real estate, and other assets. — hypericin

The effect of true power can be seen in the actions of the US government: in the Savings & Loans crisis many bankers went to jail and the US handled the situation as law basically requires. In the case of 2008 Financial Crisis where it was the big guys at Wall Street, nobody went to jail and all were bailed out. The only one that went to jail voluntarily gave himself up as the ponzi scheme was too much for him. Yet if Bernard Madoff had just kept a cool head, he might have totally survived 2008 and still could have died as a respected fund manager.

Well, usually inflation is measured by an average of what people consume and the price of housing ought to be taken into account. Usually it isn't and statisticians use things like hedonics to lower the inflation statistics. There is a real economic and political incentive to report inflation being far lower than it actually is.If you measure inflation by the cost of goods you need to survive, inflation might actually be 2.59. If you measure by your ability to buy a house, inflation is quite a bit higher. — hypericin -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Right.That vision has existed before and after Roman rule. It a Jewish constant. Whether it's Hertzl or bar Kohkba (or others in between), the goal is 1) Remove foreign hegemons from the land and 2) Re-establish Jewish self-rule. — BitconnectCarlos

But in truth Judea was a vassal of the Seleucid Empire, then become a client state of the Roman Republic, then a client state of the Parthian Empire, then came back to be a client state of the Roman Republic and later Roman Empire. It had little room to wiggle when Romans were fighting each other and then was put into line once the Romans themselves got their act together. Judea was as late as 6 AD annexed to Rome and became a Roman province, so the glorified vision of Jewish eternal resistance, always removing foreign hegemons is the likely propaganda. Of course this was before the Bar Kohkba revolt. There likely is very many of the "Quislings", which a vassal / client state tells us.

Yet patriotic history is actually quite similar anywhere: the thread of history becomes what enforces and validates our current views at the present. Many things that don't tell this narrative aren't simply "important". -

Ukraine CrisisRemember that now from last June, even officially North Korea and Russia have a mutual defense pact:

Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un signed the treaty Wednesday, during Putin’s visit to Pyongyang.

The treaty upgrades the countries' relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” It specifies that if either side goes to war after being invaded, “the other side shall provide military and other assistance with all means in its possession without delay,” according to a treaty text published Thursday by North Korean state media.

North Korea had a similar treaty with the Soviet Union, but Russia didn't have it until this year. -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Is that decolonization, really? What's the Roman colony that they wanted to decolonize? Actually those colonial efforts of Rome came later when the revolts were put down. The Jewish diaspora into Europe started during those times, so Jews have been part and parcel of Europe for a really long time.Tell that the Jews who fought the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries in order to re-establish an independent Jewish kingdom in the land of Israel. Is that not the basic idea of Zionism? — BitconnectCarlos

And you simply seem not to get it. Decolonization is a historical term. And anyway, a revolt against Romans, especially when it fails, is hardly decolonization.

For example, we don't talk about the social media of Antiquity, the bourgeoisie or the middle class in ancient Mesopotamia. Was there some class of people that could be related to them? Perhaps, but it's not correct to use such terms as the class isn't what we now call "the middle class".

Yet the other way around historical similarities or links are much used. When faced a threat, people look for similar events in history and willingly link the present to ancient history to give importance to the present. A common link, a common goal shared by generations apart sounds very nice. And people don't want to hear any historian saying that things two millennia ago were actually different.

I would say Netanyahu is far more capable and better politician than Milosevic.The Serbs tried to justify their violent ethno-nationalism in exactly the same way during the Balkan wars. Netanyahu is literally a Jewish Milošević. — Tzeentch

Yet for example the battle of Kosovo Polje, battle of Kosovo in 1389, where after ancient Serbia lost the war to the Ottoman, even if they managed to kill an Ottoman Sultan, is very important for Serbs. Just that the place where the battle was in Kosovo made Kosovo important to Milosevic. And likely the ethos that it's a similar fight now as then:

In Serbian folklore, the Kosovo Myth acquired new meanings and importance during the rise of Serbian nationalism in the 19th century as the Serbian state sought to expand, especially towards Kosovo which was still part of the Ottoman Empire. In modern discourse, the battle would come to be seen as integral to Serbian history, tradition and national identity. Vidovdan is celebrated on June 28 and is an important Serbian national and religious holiday as a memorial day for the Battle of Kosovo.

Some say the speech that Milosevic gave in the 600th anniversary at the battlefield was a starting cry for the collapse of Yugoslavia and first step on road to civil war:

-

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

?Zionism has long been understood as a decolonization movement. — BitconnectCarlos

This is quite funny, or as Benkei puts it, false.

As Benkei said, Zionism started in the 19th Century is linked to 19th Century nationalism. Also the term "decolonization" is also a very modern term not used to depict events happening in Antiquity.

For example, we can call the expansion of Rome, of Ancient Egypt or even the actions of the Mongol Horde as "Imperialism", yet with imperialism we mean expansionist policies of far later period. For example there of course is similar thinking in ancient times as "imperialism" and what we would now call "nationalism". Yet with nationalism we mean a specific ideology and thinking that came only far later. -

Scarcity of cryptocurrencies

Was in reality the one trillion, doubling of the Fed balance sheet, flagged instantly? Nope. We actually only later found out close the system had been at a total collapse. Or that corporations that didn't have any financial problems were given money, because it otherwise "would look bad".I don't think so. Of course in reality this loan would have been flagged instantly. — hypericin

First of all, the Fed doesn't have to announce and it didn't announce just how much it aided the markets during the financial crisis. Then it loaned over 1 trillion dollars. I remember that time well, nowhere was it stated that the Fed lent 1 trillion dollars. And furthermore, the way it really did assist the banks and financial institutions was very generous:Just imagine that the Fed announced that they were stimulating the economy by printing 100 trillion dollars. — hypericin

Broadly stated, the Fed chose to provide a "blank cheque" for the banks, instead of providing liquidity and taking over. It did not shut down or clean up most troubled banks; and did not force out bank management or any bank officials responsible for taking bad risks, despite the fact that most of them had major roles in driving to disaster their institutions and the financial system as a whole. This lavishing of cash and gentle treatment was the opposite of the harsh terms the U.S. had demanded when the financial sectors of emerging market economies encountered crises in the 1990s.

The Fed's balance sheet was doubled during the financial crisis. That didn't create inflation as that one trillion didn't go into the economy, because the velocity of circulation was low.

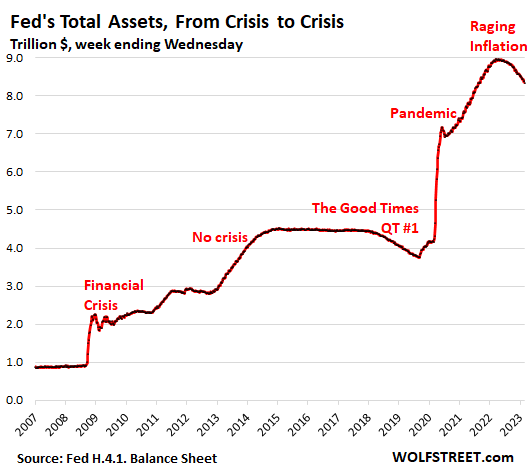

Just think for a moment: in 2003 total assets of the Federal Reserve were 730 million, less than one trillion, last Wednesday 2nd of October 2024 it was 7,046 trillion and total assets have been as high as 9 trillion in 2022. We don't see anymore the most important indicator of monetary growth, M3, but even the M2 monetary base has gone from 6 trillion to 21 trillion. Now if your simple idea of the value coming from "scarcity" be right, the a tenfold increase in Fed assets and the tripling+ of the M2 monetary base would have severe inflationary effects. Well, the annual inflation rate between 2003 and 2024 has been 2,59% annually.

Behind my example is the Fisher equation, which has a lot of truth in it: MV=PT or written out is Money Supply x Velocity of circulation = Price Level x Transactions.

In the example the money supply is hugely increased (over tenfold), yet as you just bought a Ferrari and some bottles of Champagne, the velocity of circulation is basically extremely close to 0. Yet if you give that 100 trillion to every American (which get that 303 000), the effects are devastating, because not all will just park it in the bank, it's also goes to bying stuff and services. Yet, if you just give PF members here (who can be dubious foreigners, but anyway) that 303000 dollars, then the members can enjoy the fruits of dollar having still worth. And here we see just how inflation works: those who get the "new" money first, benefit. The last one's are usually the workers that respond to seeing everything going in prices up and then start demaning increases in wages. And conveniently, they are the ones then blamed for inflation.

This is actually very important to understand, because especially the crypto-fans and the goldbugs usually just give as the sales pitch for their investment how the Fed has ballooned it's balance sheet and utter destruction of hyperinflation is just around the corner. Well, that corner can be still some way off, even if the signs aren't good when the Fed is the largest owner of US government debt and the US will continue spending as it has done until a crisis erupts. -

Scarcity of cryptocurrencies

Not actually...money doesn't work that way. It's not about scarcity, it's money moving in the economy and being used to buy stuff.If the belief spread that they might do this, the value of the dollar would plummet to 0, due to the belief in an imminent loss of scarcity. — hypericin

Assume a bank would give you the loan for mining the asteroid belt (perhaps the banker was high and thought it was just 100 million, not 100 trillion). Then it's in the books before anyone notices and later the people in the bank have this WTF-moment. Naturally some other bankers (who aren't high) don't think your collateral was OK to get the loan and let's say state a credit loss of 100 trillion (because you forgot where you put the money).

Now comes the Fed to rescue and simply bails out the bank. The loss of 100 trillion is written away and nothing has happened.Really, the dollar is just fine. (They might not publish to avoid embarrassment the data of money supply for some days you got those 100 trillion, but anyway...)

You see, the value of the dollar only goes down if that 100 trillion enters the economic system. Only then it will drive up prices and thus lowers the value of the currency. But as you have only had the time to buy a Ferrari and fifty boxes of Champagne before forgetting just where you parked the money, your actions haven't crashed the dollar. Yet if you, as the computer hack as you are, immediately donated that 100 trillion dollars to every American citizen (that's like 330 million people), who then get 303 000 dollars each, you bet there's going to be a huge inflation spike and the dollar will go down, not to zero, but down. Think about it: what would you do if you are given 303 000 dollars? Especially when you understand that everybody else has been given 303 000 dollars. Perhaps people would simply first pay their loans back, but then they would simply start to compete on what they can buy with the money.

And this in a way has already happened in real life: during the Covid pandemic the government sent helicopter money to Americans, because there were the restrictions on working. The bout of inflation was totally foreseeable, even if usual, they lied about the effects of this. Yet when the banking crisis hit and the financial sector had huge losses, the aid the Fed gave to the banks didn't create inflation. The Fed just covered the losses, no money went into the economy. The banks didn't lend so nothing happened (except perhaps mild deflation and a recession).

Hence if there's 100 trillion in some obscure derivatives market, that amount won't wreck the price of the dollar... as long as those 100 trillion stay in the obscure derivatives market! And this is why if there really would be an Uncle Scrooge McDuck, who would be the richest person (duck) in the World who would have his wealth in coins, he could be out there. As he uses the money simply to swim in it, the value of the currency is totally Ok. Sitting (or swimming) on the money doesn't create inflation, hence it isn't the amount itself that is important, because the miserly duck won't use the money to buy stuff.

-

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Don't forget South America, Central America and the Caribbean. The Continent of America isn't just the US.. In any case, yes North America was colonized — BitconnectCarlos

?but it also underwent large-scale decolonization. — BitconnectCarlos

You mean Latin America and North America got Independent? Especially when population transfer (meaning settlers coming in), American Continent comes to mind as the example. And of course with Islam people converted to the religion, so the people weren't replaced, but conquered. There weren't so many Arabs actually at the time of Mohammad.

You're really serious? New interpretations for Zionism. Besides, without going to Biblical times, it was the Romans and Emperor Hadrian, that started rooting out Jews from their land (for example banned Jews from Jerusalem) and settling other people to the land, so that's a bit earlier than the Muslims. Like half a millennium earlier or so.The idea of decolonizing Muslim lands (e.g. Zionism) — BitconnectCarlos -

Scarcity of cryptocurrencies

Not actually.They are willing to buy to the degree it is scarce. As I said scarcity is a necessary but insufficient condition for value. — hypericin

There's no scarcity of let's say the US dollar. Only that the Central Bank won't do this. But with a few pushes on a computer, they could make tomorrow 100 trillion dollars. Just as no bank can give you a 50 year 100 trillion dollar bullet loan to mine the Asteroid belt, even if you would have this awesome business plan to do it. Likely the Central Bank or the Financial Regulator would halt the bank giving you such a loan.

Yet if they would go along with your loan plan, once you sign it, you have just created that 100 trillion.

How could that be scarcity in the meaning that we usually understand it? -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West Bank

Somebody is a bit exaggerating here. :snicker:The greatest & most brutal settler-colonial project in history -- Islamic rule — BitconnectCarlos

I think the colonization of a whole large continent would still count as the greatest settler-colonial project in history.

And I'm not talking about Australia. -

Scarcity of cryptocurrenciesJust scarcity isn't a reason for demand.

If people think something is valuable and are willing to buy it, it's valuable.

ssu

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum