Comments

-

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemGiving the human race a chance is a matter for every one of its members that has the cognitive ability to consider it. You are either part of the solution or part of the problem. I don't accept the term utopia and I don't desire such. I desire continued effort to improve the lives of all human beings so that fewer of us live with constant despair or/and suffering. Such despair can even have the horrible effect of turning good, deep thinking humans into misanthropic, pessimistic, antinatalists. — universeness

The human race is not alone, but part of a larger whole. 'Being part of' means it is nothing without it, cannot exist without it.

Constant improvement of human beings, via science/growth, at the cost of the rest of the whole cannot be improvement is what socialists don't seem to get.

But since you were already listening to that song in the 70's and 80's, I probably won't change your mind at this point ;-).

Thank you too. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemYes you do, so let's keep chattering with each other all over the world, with that general goal in mind. There is a lot of time left based on the expected natural lifespan of our pale blue dot planet. We have only been at this 'create a good/fair/equitable/global human civilisation,' which has earned the right to and can be trusted with 'stewardship' of the Earth, endeavour for around 10,000 tears. Okay, so far, its been mainly 10,000 years of tears and slaughter due to failed attempts and nasty individual human and groups. But Carl Sagan's cosmic calendar shows a time duration of 10,000 years to be a drop of water into a vast cosmic ocean.

As I have politely typed many times, in consideration of the potential duration of time available to our ever-busy procreating species, "Give us a f****** chance!" A single human lifespan is very brief.

The cause of the true socialist, is to progress the cause of true socialism, so that's my cause within my own short lifespan. Unless of course I can live long enough for science to invent that which will allow me the option of living longer. — universeness

Nice rant, seriously I can appreciate some real passion shining through. It made me think of this songs :

[...]

In the year 9595

I'm kinda wonderin' if man is gonna be alive

He's taken everything this old earth can give

And he ain't put back nothing

Now it's been ten thousand years

Man has cried a billion tears

For what, he never knew, now man's reign is through

[...]

Ultimately I'm probably more of an ecologist than a socialist. The laws of physics, ecology and biology take precedence over what we want, over what we can agree to.

I do want to give man a chance, I really do, but I don't think it's up to me... Socialist utopia may just not be in the cards.

Take care. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemSo yes, we have to look to the long term and create checks and balances backed by global legislation which will outlast individual human lifespans. — universeness

Part of the problem, and reason, we don't already have that is because what 'we' decide is partly determined by those that are in power. At no point in history we get to actually step outside these power-dynamics, and draw up these rules from some fair and balanced point of view.

And global legislation is even more difficult because you need actual consensus for that, because there is no decision organ with majority rule or something like that...

I mean I agree that this is how you would need to do it (if you could do it), on a global level, but that isn't going to happen it seems to me. The last 50 years we saw the opposite movement with globalization and neo-liberal abolishment of barriers.

Yes and I agree that such is necessary and will always be so but it's the checks and balances which will prevent the historical abuses of power we have memorialised. I can describe the kind of checks and balances I am typing about if you wish. I have done so in other threads. They are not of course from my original thinking, they have been around for centuries and attempts have been made to establish and apply them. Most Western political systems have quite good examples but few have the power or structure they need to effectively prevent abuses of power or the excesses of unfettered capitalism. — universeness

We probably only would know if they work if they have been put into practice. As a legal practitioner, if there is one thing I have learned it is that people always find loopholes to circumvent the rules. People seem to think rules are the solution to everything, they rarely are.

We don't currently, your right, but we must get it right or we will not survive as one human race, living on one little pale blue dot of a planet. We are all responsible for Putin who now threatens the existence of our species. One pathetic little prat should never have been able to do what he is doing. — universeness

Yeah, after WWII never before we had so much consensus and momentum to draft up systems to prevent future atrocities. But even then the powers that be couldn't resist the temptation to introduce rules that consolidated their power, essentially making the UN toothless going forward.

Geo-politics is a game of countries doing what the can get away with. Only when something really really bad happens, I could see countries actually coming together to draft something up that is fair and balanced.

No it doesn't, for me, it proves that we need to demand economic parity for all human beings and only allow authority which is under effective scrutiny and can be removed EASILY due to the checks and balances in place against abuse of power/cult of personality or celebrity/mental illness/attempts to establish totalitarian regimes or autocracies/aristocracies/plutocracies. — universeness

Like I said what we want doesn't necessarily have anything to do with what we can do. I probably agree all of that would be nice in theory, I'm just not so sure we can get there. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemOne snowball can create an avalanche. I don't dismiss the 'wishes' or determinations of any individual or a group you define as 'we', as impotent. Doing so, can often allow the nefarious to gain power and influence. I act based on my 'wishes.' — universeness

If we are talking about societal structures, it's about the long term, right? Maybe the founders of google had all the best intentions, and with those initial intentions amassing power seems a good thing... problem is they aren't going to be in power for ever even if the structure keeps on existing. After Lenin came Stalin.

Like I said in my response to Xtrix, when you get to a certain number of people hierarchies seem to become necessary. And with that kind of power relations, some will have more power to determine how the system looks like going forward. And because of that, a certain type of personality seems to rise to the top etc etc...

I don't think we have as much control over these systems as we'd like to think, and no matter the original intentions, it seems like it tends to go in certain directions.

Perhaps you are conflating historical aristocrats with modern celebrity culture. The French aristos only had interest in what their fellow aristos thought of them or/and the King/Queens inner circle. They had little interest/conception/concern about what the unimportant/starving/abused mass of the French peasantry thought about them. The same applies to all historical aristocracies. Such an aloof attitude proved to be their biggest mistake. — universeness

Well sure, I'm under no illusion that they have been a particularly nice group of people, but the fact that they were overthrown because of their aloof attitude kindof proofs my point, namely that they have to take the wants of the peasantry into account at least to some extend. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist System

I never said I fully believe the basic assumption either (check my last line), but I do think maybe there's something to it. 'That something' is always hard to determine and certainly hard to proof because we are speaking of complex emergent structures... who really knows what the limits are?

And look, if your only argument is that you don't want it to be so - which it usually is when people fight these things with a lot of zeal - I kindly bow out of the discussion. What we wish has nothing to do with what is necessarily the case...

What?? Give me a historical or current example of a well-behaved aristocratic family who were benevolent/altruistic/philanthropic towards the majority and I will provide many, many other examples of historical aristocratic nasties. — universeness

I'm not saying aristocrats are altruistic philanthropes, I'm just saying that there are limits to what they can get away with because they at least have to uphold some public image, unlike faceless capitalists who operate entirely behind the scenes. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemI personally don’t think we can make that assumption. It’s not simply about removing suppression— it’s also about positive design: beliefs, values, culture, education. Actively encouraging other values like love, compassion, good will, tolerance, strength, confidence — this is just as important as removing factors that suppress these values. — Xtrix

I think I agree. Question is maybe how does one organise those into a society, practically?

We moderns and atheists usually don't have much time for tradition or religion, but at least those did provide a positive account..

Now we only have secular states that have to guarantee neutrality and plurality, and can't give any 'thick' account of what values our societies should be build around. This has its benefits no doubt, but then again maybe that did open us up for capitalism to fill in the void.

II can’t help but be reminded, again and again, of both Plato and Nietzsche when it comes to a vision of what society could be like. They tend to favor aristocracy. So do I — but in the very long term. In the meantime, I think communalism is the proper direction as a countervailing force to the extreme form of capitalism we’ve been living under. — Xtrix

I think scale is important.

Maybe in smaller groups with little specialisation some form of communalism was the default organisational form. Maybe that is indeed even our dominant instinct because we presumably evolved in such circumstances..

But I think as soon a we pass a certain number of people, as soon as we started organising into cities, some form of hierarchy perhaps became necessary, or at least more practical.

And if we need to have these type of power relations anyway, an aristocracy probably makes sense lest we devolve into an other type and even less desirable form of oligarchy. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemThe French might fight against you on that idea. I would help them do so.

Why would you favour an aristocracy? at any time? — universeness

All systems tend to oligarchy.... combined with.... noblesse oblige.

Now we nominally have democracy, but in practice power seems to be in the hands of a few capitalists anyway.

So even though the system was supposed to be something else, we still ended up with some type of oligarchy.

The difference then is that now the oligarchy consists of nameless capitalists who have no public image or values to uphold, because 'technically' they aren't even in power.

Aristocrats at least has a reputation and values to uphold by virtue of the official position they hold.

If we need to have an oligarchy, aristocracy would seem to be one of the better versions of that.

Anyway, this ofcourse assumes we always end up with an oligarchy, which isn't a given by any means,... but this would be a reason to favour it. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemPeople who take 18th century values seriously are against concentration of power. After all the doctrines of the enlightenment held that individuals should be free from the coercion of concentrated power. The kind of concentrated power that they were thinking about was the church, and the state, and the feudal system, and so on, and you could kind of imagine a population of relatively equal people who would not be controlled by those private powers. But in the subsequent era, a new form of power developed — namely, corporations — with highly concentrated power over decision making in economic life, i.e., what’s produced, what’s distributed, what’s invested, and so forth, is narrowly concentrated.

The public mind might have funny ideas about democracy, which says that we should not be forced to simply rent ourselves to the people who own the country and own its institutions, rather that we should play a role in determining what those institutions do — that’s democracy. If we were to move towards democracy (and I think “democracy” even in the 18th century sense) we would say that there should be no maldistribution of power in determining what’s produced and distributed, etc. — rather that’s a problem for the entire community.

And in my own personal view, unless we move in that direction, human society probably isn’t going to survive.

I mean, the idea of care for others, and concern for other people’s needs, and concern for a fragile environment that must sustain future generations — all of these things are part of human nature. These are elements of human nature that are suppressed in a social and cultural system which is designed to maximize personal gain, and I think we must try to overcome that suppression, and that’s in fact what democracy could bring about — it could lead to the expression of other human needs and values that tend to be suppressed under the institutional structure of private power and private profit.

This is interesting in that it kindof lays bare some of the assumptions that are being made in enlightenment/liberalist ideology.

Maybe it is the obvious thing to try when confronted with concentrated power, to try to get rid of it, and try to distribute it evenly over the population.... that sounds perfectly reasonable on the surface at least.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating however and experiments to achieve this, haven't been all that successful historically it seems to me. Maybe one can argue over whether it's the idea or the execution that failed... but my intuition is that it's no fluke that capitalism developed in the society that championed individual liberties over everything else.

Power hates a vacuum. If we destroy traditions that uphold certain values, something else will look to fill the void. Maybe it is the case that commerce/capitalists could jump in an manipulate the rest of society precisely because it didn't have to compete anymore with traditional value-systems that have been systematically destroyed after the enlightenment?

The idea of liberalism, enlightenment and democracy seems to be predicated on the assumption that the good parts of human nature automatically will come to the fore if only we could end oppression and suppression of said values. Can we really make that assumption? -

Ukraine CrisisWe've had the technology for many decades. The only reason it's not fleshed out is because there wasn't any weapon capability as a byproduct. You know, if you have a normal nuclear power plant, you could use some of the nuclear matter used for nuclear weapons as a side gig. Thorium is too good for bad nations. — Christoffer

The main reason I'd say is that the government isn't embarking on big societal projects like it used to, the socio-political climate has changed ;-). I doubt that technology is ready to start building actual functioning plants, but I'm not an expert so I could be wrong on that.

It's a push in that it demands another solution. And "scramble" to stay afloat is not really true. An economic crisis may look like the one in 2008, but did that "scramble to stay afloat"? There's still plenty of capital to invest in new solutions, it's just that the financial world always need to balance the entire economy so as to not break regular folks. However, since regular folks seem to not care about climate change and politicians are not willing to do what it takes, a crisis that pushes everyone out of their comfort zone will lead to hard times in the short terms, but better times after a few years. Also remember the jobs that gets created by investing in new technologies. — Christoffer

This is all assuming the crisis won't be much worse and debilitating for years.

And this is what I think gets pushed when we can't rely on oil and gas. People feel the ground shake under them and they will start investing much quicker. — Christoffer

Gasprices rose something like 400% last year without the war or sanctions, one would think that would be incentive enough to try something else. -

Ukraine CrisisMy point is that tanking the economy is probably never a push towards other solutions,

— ChatteringMonkey

This is doubtful. As they say, necessity is the mother of invention (not talking Zappa here, who was extremely creative himself). Take The Manhattan Project for example. When you get hundreds, or even thousands of scientists working together, in a network, there is a lot more efficiency than a handful of scientists here, and a handful there, with intellectual property guarded by secrecy. Fusion, or other new ideas, might not be as far away as you think. — Metaphysician Undercover

I don't think the saying really applies here because there's no invention that can deal with that necessity short term. It's not like there is a lot of unexplored territory in energy-physics where one might expect radical new technologies just around the corner. Every new development costs exponentially more resources now, in fundamental research, in time and R&D, precisely because so much has already been put in over the years. All the 'low hanging fruit' is long gone. If some new technology could provide us with more energy, I'd fully expect it to take 50 to 100 years to develop. By then we'll be living in a totally different world I'd expect.

But sure, long term maybe it will spur the EU to reconsider it's energy-strategy. I'd argue that this is already happening, as climate change is putting pressure on fossil fuels and people are starting to realize that renewables can't really replace them. This is one more argument for nuclear, which seems to be the only technology (maybe with fusion in the future) that can provide us the energy we need. In short I'd argue that the necessity is already there, but we need time and resources to do it. A severe economical crisis with no doubt nasty political consequences, would probably not help, is my guess. -

Ukraine CrisisI think you should check that again. — Christoffer

I did check it, a lot... renewables just will not work on the scale needed. And even if they would, you'd need huge swats of land for it which would be an ecological disaster on it's own. Nevermind the waste afterwards, and the sheer amounts of resources needed to keep building them in large enough quantity...

And it doesn't matter, it has to be done anyway, whatever people think about it or however hard it hits the economy, it has to be done in order to decrease the rate of climate change. — Christoffer

We need to do whatever is the least worst, which is not as clear-cut as one might think ;-)

On top of that, since the investment in improvements of renewables has skyrocketed in a very short period of time, all while we just recently had a major step forward for fusion energy, which changed the projected time-frame for when we might solve that problem. If nothing else we also have Thorium nuclear power with power plant designs that can utilize nuclear waste almost until they're half-lifed to irrelevant levels before storage. — Christoffer

From what I've gleaned, renewables can only be part of mix at best, fusion is still 50 years into the future even with recent improvements, and the new type of nuclear reactors are not entirely ready to be used either. Anyway I agree that nuclear is the way to go, but this is not something that can get done in the the time-frame needed to stop climate change.

My point is that we NEED to have a push towards other solutions than gas and oil and we just got this with moving away from Russia's export of it. So while people can take the pain that creates as a sign of support towards Ukraine, that kind of pain could never be endured just on the basis of "we need to do this for the environment". People don't care about the environment, they care about people suffering. We can argue this is because they're stupid and don't connect the dots of how the environment create suffering, but the fact is that we hit a lot of flies in one hit at the moment. We can weaken Russia's hold on the west, remove their trading diplomacy cards so we don't have to be puppets of the oligarchs and Putin's ego, all while pushing the necessary push towards better solutions than oil and gas. Even if we don't go renewable soon, just build Thorium power plants. I feel like people don't know how safe these designs really are, it's way better than any other solution at the moment until renewable match up with it. — Christoffer

My point is that tanking the economy is probably never a push towards other solutions, because as you scramble to stay afloat, the last thing you want to do is make big investments in future-oriented transitions.

I agree on nuclear, if they are ready, but you need large coordinated investment for that. They are the future, but if you're too busy trying to put out fires left and right, you typically don't think about the far future. -

Ukraine CrisisI'd say, rip the band-aid already. The world needs to move towards sustainable energy and this could be a good way to speed that up. Even if it would create enormous economic problems in the short term, it can be done. — Christoffer

I don't think it can be done. Energy-transition is a process that would take decades even if there was a consensus on the way to go... you can only speed it up so much, before you run into physical, engineering or even economical limits.

Without fossil fuels you basically have renewables and nuclear energy. Renewables will not get it done any time soon, and probably never, because they just are not that efficient, reliable, easy to use, and not even that green to begin with. Nuclear could've done it if they committed to it decades ago, but as it stands they are still in the process of phasing out nuclear in a lot of the EU-countries because of anti-nuclear ideological sentiments of the past.

Energy prices were already shy-high in Europe before the war, it just came out a pandemic that caused massive debt for governments that tried to prop up the economy, inflation was already higher than in a very long time... chances are you completely tank the economy by raising energy-prices even further in a precarious moment. And completely tanking the economy seems like the worst thing one could do to speed up energy-transition, because of the enormous amounts of investments and resources needed for such transition.

Anyway, I'm not saying Europe shouldn't consider it, just that we need to realize what is a stake here.... energy is life. -

The Secret History of Western Esotericism.

Well I'd say the esoteric is whatever Western tradition ignores.... and Western tradition is more than Western philosophy I suppose, we did have a couple of religions playing a role in our history.That's something that is lacking in Western philosophy, which tends to focus on mind/pure thought (forgetting the body), and which gets a whole lot more attention in eastern philosophy (rites, meditation, etc.). So I do think this is an important topic, but I would rather want to explore it from a psychological/physiological naturalist point of view, rather than from a magical supra-natural point of view... if that makes sense.

— ChatteringMonkey

The esoteric as whatever Western philosophy neglects or denies, is almost a tautology. — unenlightened

But I wonder how a naturalist account of the supernatural, or a rational account of the irrational can possibly work. I'll have to wait and see I suppose... — unenlightened

Yeah I did and do wonder about that tension too. I'd say at this point in time we did arrive at the conclusion, via reason/empirical data, that the irrational, myth/stories are important for us humans. That's to say the idea that we should be perfectly rational beings was by itself not a very reasonable or scientifically justified conclusion.

The question still remains, how does one deal with the irrational with reason? The answer is, I suppose, one doesn't... one recognizes that ones reason isn't suited for everything and leaves some space for exploration of the irrational via arts, music, practicing rituals etc... Isn't this precisely the problem with the magical or esoteric, that one is still trying to use an essentially rational methodology to things that aren't really suited for it? What I mean is that one is looking at these things as if they have a "literal" meaning, instead of metaphorical meanings. -

The Secret History of Western Esotericism.I would appreciate particularly the sceptical response to Episode 5: Methodologies for the Study of Magic. However the warning about glamour particularly applies to the sceptic if they assume a superior position. One of the aspects of magic discussed is that of its normativity - magic as foreign/illegitimate religion. The high priests of science have cast out all the demons? Then why are we not in heaven already? — unenlightened

Ok, there's two meanings put forward of the word/concept magic, first order and second order.

The first order meaning revolves around ingroup-outgroup perspectives being taking on some sets of rituals, where in-group rituals are seen as legitimate and out-group rituals as illegitimate, magic... i.e. magic used as a political term. I totally buy that this distinction isn't really justified from a more objective point of view one would want to take on the matter. The fact that some subset of rituals is deemed illegimate however, on the basis of some political/objectively unjustified criterium, doesn't really make one want to re-evaluate the excluded rituals, if one doesn't believe in religious ritual to begin with, legitimate or otherwise,. Put another way, If one is an atheist, it doesn't really matter if it's magic or legitimate religious ritual... both seem equally unpalatable.

Looking for a second order meaning, a more objective meaning one could use as a scholar, seems a lot more difficult. One gets something that remains nebulous at best, as the podcast-host has to admit. It's a word that could denote something like rituals that seek to elicit some effect, maybe or maybe not in connection with the will. So for the skeptic there doesn't seem a whole lot to go on there.

I will say, I do think the practice of rituals, or rather the omission of ritual in Western Philosophy for the most part, is something that does interest me. That's something that is lacking in Western philosophy, which tends to focus on mind/pure thought (forgetting the body). This does get a whole lot more attention in eastern philosophy (rites, meditation, etc.). So I do think this is an important topic, but I would rather want to explore it from a psychological/physiological naturalist point of view, rather than from a magical supra-natural point of view... if that makes sense. -

The Secret History of Western Esotericism.Part of the significance that I want to look at or for in the thread discussion is how the perennial new-age spiritual revival relates to recent, particularly right wing, history, from The Nazis to to QAnon. — unenlightened

My guess is it doesn't, not in any real way anyway.

I've listened to the first 3 episodes, and one of the ideas put forward of the real history of the secret history of Western esotericism is that there isn't one unified movement, group of coherent ideas or linear hermeneutics.

I think there's a word for this - can't think of it right now - but my take is that ideas and concepts get appropriated from one generation to the next, without there necessarily being a continuity in meaning.... But they do carry some weight, an aura (because they do hang somewhere in our memories/culture I guess) which can be used as a means to gain some sway.

That's how I look at most of these phenomena. There's some real desire for answers to the situations people find themselves in, to the state of the world, for political influence maybe... which is a feeling more then something that is already clearly defined. And then this gets filled up with a whatever ideas that sound like they might fit in to create a semblance of coherence to the stories people want to tell themselves.

I do appreciate the more scholarly angle he is taking on the topic, he really does a good job. But I don't know how much I can handle of this particular topic, maybe it really doesn't deserve this much attention. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemMaybe...but that means enormous suffering that will be felt mostly -- as always -- by the poor and working classes. It means worldwide depression. They've gotten themselves into a game where they're now "too big to fail," and so the government serves as a backstop for them, preventing them from failing. On and on we go.

I'd much prefer massive legal and regulatory reforms, but that's not going to happen either. What's more is that we're really out of time. So if the entire system collapses, perhaps that's the last best hope we have?

There's always the people, of course. That's my real hope. Unfortunately millions of people are far too divided by our media bubbles, too tired from work, too sick from our lifestyles, too medicated, too drugged out, or too "amused" to know or care about the imminent catastrophe already unfolding. — Xtrix

My hope is people too in some way, but not in a typical direct political way, like people voting for reforms to the cosmopolitan global capitalist system that we have. I can't see that happening.

I think solutions will be local, smaller scale, communal etc... just people looking to pick up where the system breaks down, out of necessity or just because it makes more sense. There are already constant efforts at these more grassroots local initiatives, but they are not easy or all that successful because you still have that mainstream monolith they have to compete with that provides 'easy answers' for most people. The hope is that as it breaks down, these initiatives will get more traction as more people are forced-out/realize the terminal state of the system.

I guess my original point was that legal reforms and the like are only of consequence if one believes that the system can be saved. If one doesn't, then they don't really matter. That's the awkward political position I find myself in as of late, I think all traditional political answers are inconsequential because they seem to assume a future that I don't think is even possible. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist System

Okay to attempt to give a more constructive response to your question ;-).

The whole system is the problem right?

You can't change the whole system is my answer (and not only mine). It just doesn't work because the system works around little fissures and the like... commercializing ('colonizing') anything and everything that attempts to change it from "within". Politics is futile for much of the same reason... because by the time you get to anything worthwhile, it has to be watered down that much that it isn't worth it anymore anyway.

The way it will/has to go, is breakdown. Parts of the system will breakdown, cease to function and other things will take its place out of necessity. That's the charm of alternative ways of living, things like perma-culture, that they create alternative means of subsistence not directly tied to the mainstream economy... without trying to be overtly political. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemI don't really expect an answer to this... seriously, what do we expect people to say? That almost everything we do is a ruse, propped up by inequality or fossil fuels, both highly toxic in their own ways. Most people can't live in that space.

[silence] -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemI think the only "solution" is to let the whole system collapse, probably better sooner than later... and see what can grow after that.

The "system" is predicated on the idea that "we" can secure a future for ourselves apart and above of the rest of the world. This has turned out to be a mistake... no matter the disavowment of this mistake, at some time we will have to recon with it. If we wait longer, it'll probably be that much harder. — ChatteringMonkey

This all probably has a very "Hari Seldon"- vibe to it... but I think it true for the most part. It's just basic (energy) physiques unfortunately. -

Goals and Solutions for a Capitalist SystemGiven this analysis, the only question left is: what exactly do we do about it? In other words, what about solutions? What goals are we working towards? — Xtrix

I think the only "solution" is to let the whole system collapse, probably better sooner than later... and see what can grow after that.

The "system" is predicated on the idea that "we" can secure a future for ourselves apart and above of the rest of the world. This has turned out to be a mistake... no matter the disavowment of this mistake, at some time we will have to recon with it. If we wait longer, it'll probably be that much harder. -

The project of Metaphysics... and maybe all philosophyThe project of metaphysics is bullshit... seriously ask yourself why would you believe in something that has no apparent reason, nor any sense evidence at all (which by definition it has not).

There is no reason at all.... to believe in any of it. -

COP26 in GlasgowMarket mechanism creates the obvious limits. But if those are disregarded, then simply you will have "official" prices that nobody can get the stuff and then a black market. Perhaps the following remark on what you later note sheds light what I'm trying to say. — ssu

I think I do get what you are trying to say, oil prices will rise, renewables will get cheaper... and so in the end the idea is that market will sort it out by pricing out fossil fuels in favour of renewables.

I just don't think you will end up with anything like the same kind of economy because they are not that interchangeable as one might think, i.e. one energy for another type of energy. Renewables are more expensive to begin with, not as reliable (which means you need storage which makes it even more expensive), you need a far more expanded electric net if you want to switch to electricity, you don't have the same usefull byproducts as oil etc etc..

It not just one thing that needs to be resolved, the entire system is geared around fossil fuels, as I believe are our ideas about economic growth, capitalism and globalization too. Energy out of fossil fuels is I think not just another resource the market can sort, it's the basis on which the entire industrial system was build.

Well, energy policies DO MATTER. The fixation on the US based fossil fuel guzzling economy doesn't tell the truth. Let's compare it with another country. — ssu

End result? An actual real difference. — ssu

A smaller difference then one might think. The graphs only show electricity production, which is only what, generally about 20% of all energy-usage? Non-electricity energy usage is still predominately fossil fuels in both countries.

Have we really tried? — ssu

Sure, not that hard probably, but that's part of the problem no? We can't really make abstraction of our social and political systems, as if they don't exist or will magically change.

You are totally correct and I agree with you. It isn't at all simple. And likely there isn't the actual political will.

The worst thing is that people won't understand it when or as the climate change is happening. Because the real outcome of draughts, famines, economic crises is political crises and wars. And those have a different narrative: it was this and that politician, it was these factions that started the conflict. Nowhere do you see an link to some political conflict to truly happened because of climate change. Now every smart facet will understand this (like the US Armed Forces), but it simply won't go down to the level of political narrative on how we explain political developments.

In the end, people will take the weather as "Gods will", if the link isn't as obvious as the London smog was to how houses were heated back then. This is the real problem. — ssu

There isn't political will because nobody wants to hear that we have to de-grow, that they probably will have to do with less. No political party can push that program and get elected, which is kind of interesting in its own right... the fact that we apparently have a political system that just can't have de-growth as an end.

I still am an optimist and think that we can prevail. We are still standing on the "shoulders of giants" and all that gathered knowledge that science has given us is available for us. The economy hasn't collapsed as it did during antiquity and we haven't gone full backward that we would be going back to the "dark ages part 2". I'm not sure that it will happen. I think it's going to be just a bumpy road. After all, we are living during a global pandemic right now, ChatteringMonkey. :mask: — ssu

Maybe... I suppose these things always have to end on a note of hope. Knowledge and technology is the biggest unknown certainly, I wonder how much of it a difference it makes on it's own when you take away the energy. -

COP26 in GlasgowThe long time question is of course if we need economic growth after we have hit peak human population. More prosperous people have less children, and when the fertility rate is well below 2, do we in the long run need perpetual growth? It's more a like a question for our debt-based monetary system, which needs perpetual growth itself. But otherwise, I don't think so. — ssu

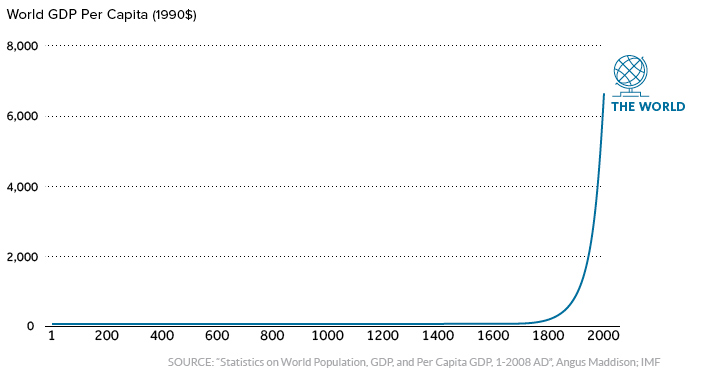

I'm going to start here, because I don't know what it is that people just keep believing perpetual growth is even possible in theory. It isn't, resources and energy are finite. If you keep taking a percentage growth of what has previously grown a percentage, you get exponentials and bump against that finitude of resources pretty quick. It's not a serious question, we can't grow perpetually. The only question is how long can we grow before we bump against all sorts of limits?

Hmm, looking at this statistic, comes to my mind a statistic of the consumption of whale oil. The 19th century likely would produce such a graph. Yep, whales were really hunted down to extinction in the 19th Century, but then came an alternate way of producing similar oil. — ssu

It would be similar except there is no alternative to fossil fuels once used up. You cannot get ease of use, energy density and other byproducts from renewables.

Do notice what I said. If alternative energies ARE MORE CHEAPER than fossil fuels, then the transformation will be rapid. And do notice what is happening in the World. Things don't happen in an instant, but they do change in decades. — ssu

If they are cheaper than fossil fuels then transformation will be rapid, seem like it would be evidentially true, but I don't think it necessarily is.

At some point fossil fuels will become so expensive that it costs more energy to extract them than you are getting from the extraction. Let's call that a negative Return On Energy (ROE). If ROE is negative it's not worth is from an energy-point of view to extract them... maybe you'd still do it for other applications like plastics, lubricants etc etc, but not for the energy.

If alternative energies are only cheaper than fossil fuels when ROE of it becomes negative, than we wouldn't transform rapidly because it wouldn't be worth it, either way.

I disagree. There are alternatives that are totally realistic. Just look at how for instance the price of solar energy has come down. In fact, the situation where non-fossil fuels are cheaper than fossil fuels isn't at all a distant hypothetical anymore. It is starting to be reality. — ssu

Yeah solar-panels that are produced by a fossil-fueled economy and mass-production process. I'd want to see how that works without fossil-fuels to jump-start the whole process.

And even if it would be theoretically possible, it surely isn't in practice as we haven't even succeeded to reduce fossils fuels one iota since we started trying to reduce them consciously. Consumption of new energies just get stacked on consumption of previous sources of energy. No way we will succeed in replacing that mountain of fossil fuels with renewables in time:

The real hurdle are niche things like aircraft. But here the also there is a lot of investment in hydrogen fueled or electric aircraft. (Hydrogen can be made by electrolysis without causing emissions) — ssu

Hydrogen is no source of energy, just a way to store it. It is energy negative to produce and we don't find it on earth. If you want to produce it without emissions then you need to rely on renewables that aren't all that energy-efficient to begin with...

And let's not forget that aside from the question of cheap energy, oil-byproducts are also used almost everywhere in production-processes. Lubricants, plastics, etc etc... I don't know if you even can have a "production-proces" without oil.

The real problems happen when don't invest and just ruin our economies. Then there isn't going to be any investment and then we will have to rely on fossil fuels just to keep our present energy consumption. Ruining the global economy will create political instability and at worst widespread war. Not much investment will then go to climate change. And just notice how for example the US energy consumption has leveled off in this millennium. And do note from below how huge the level of fossil fuels are in the US. But in for example France, it's a different matter (as they have opted smartly for nuclear energy). — ssu

The really real problems happen when we run out of cheap energy to keep feeding a growing economy. That may be because of lack of investements, or maybe there just isn't cheap enough energy to be found or invested in anymore to be able to mass-produce a tennisball in china and sell it somewhere in Europe.

I dunno,I think people just all to easily gloss over the fact that it's not evident (not possible I'd say) to just replace oil and gas, which is solar-energy densely-stored over millennia gushing out of the ground.

So I do disagree in the idea that the global economy cannot grow without fossil fuels. The way things are going now, with little and sporadic investment in technology, with pompous declarations by politically correct politicians (who know people don't remember the promises six months from now), it's going to be a bumpy ride.

Now things might prevail somehow, but likely that isn't enough for those who are against the how our society works in general. They surely will be as disappointed as now are, even if we do manage along for the next one or two hundred years without any cultural collapse. — ssu

I think aside from the obvious political and moral failings of our societies and leaders, there's also a non-moral, 'fated' side to this tragedy. We were born and raised in the candy-store, never to know anything else, how could we realistically conceive and really feel like it was not to last? Fossil-fuels being such a potent, yet one time source of energy, really threw us a nasty curve-ball there. -

COP26 in Glasgow

Since economic growth tracks energy consumption, it doesn't look to hot for the economy going forward. -

COP26 in GlasgowWake up, the whole idea of economic growth will seem parochial in a couple of decades.

-

COP26 in GlasgowThere is no juxtaposition SSU.

Without further use of fossil fuels there can be no growth economy as we know it.

With further use of fossil fuels there can be no livable planet.

You might think that this is merely an ideological (juxta)position, and that there are other options than those two... but that's because you haven't looked into the specifics of those 'alternatives'. There are no alternatives that work because fossil fuels were a one-time, easy to use energy-dense source of energy.

Now if there indeed needs to be made a choice between those two, then the choice should be pretty clear, because without a livable planet you can have no economy.

The whole discussion is moot anyway because fossil fuels (and other resources too) are a limited resource. Even if we would want to keep using them, we can't because we will run out of them soon enough. The economy will have to collapse no matter how you want to look at it. -

Philosophical Woodcutters WantedAgreed, CM - what is your understanding of what the recovery process from such a worldview might be? — Joshua Jones

I'm not sure I completely understand the question. Are you asking for what the recovery process from the worldview would be, as if the worldview is the sickness? Or are you asking what the recovery process for such a world would look like?

I'm assuming the former, though I'm not sure I agree with the idea that it is something that one needs "to recover from"... maybe i'd rather say "cope with"?

Though I think I always had the intuition somehow that this world was not to last, it only recently fully and consciously dawned on me. Since I'm still very much in the process of re-calibrating and adjusting to a new horizon so to speak... maybe it is to early for me to say how to best deal with it.

Or maybe that is precisely how one starts to deals with it, by re-evaluating and adjusting ones plans and values so that they re-align with a fundamentally changed future. Yes, that's how I will be starting I guess, by committing to what I think I know... and re-evaluating things in light of that, which will probably take a good while. -

Is essentialism a mistake, due to our wishful thinking? (Argument + criticism)One does see this sort of argument often in philosophy of religion as well for example, some philosophers seem to claim that there is no afterlife, or that religious text are just fairy tales, and then go on to say that we only believe in those things because we don't want to die (among other things), but that does not prove (as they sometimes seem to imply) that there is no afterlife or that religious texts are just fairy tales. — Amalac

It's no proof, right... but it is a sort of explanation for why people are holding those beliefs if you already assume they don't hold those beliefs because they are true. -

Is essentialism a mistake, due to our wishful thinking? (Argument + criticism)

I don't think he is making an argument there at all, he seem to be just stating what he thinks is the case, and why we tend to believe in essences... i.e. because we wish it.

But it seems to me that this is a non-sequitur: it does not follow from the fact that we wish something to be the case, that it is not the case — Amalac

Yes, and it cuts both ways, wishing doesn't have a necessary relation with truth either way... there are just putting the emphasis on the other way (because that is where the tradition they are criticizing was coming from I guess). -

Philosophical Woodcutters Wanted"The world as we know it" is basically western capitalist growth model exported to the rest of the world.

That kind of model only became possible because we found a way to use fossil fuels that are incredibly energy-dense and easy to use (economic growth is a function of the amount of energy consumed).

As fossil fuels are finite and non-renewable, or we have to stop using them anyway, it seems that energy will become a lot more expensive as we scramble to replace fossil fuels.

So then, here we are, a bunch of people expecting a certain standard of living because that's all we have ever known... while at the same time that standard seems unsustainable because the energy isn't there longterm. Add to that that we have, along the way, seriously degraded the world we previously could rely on for subsistence... and you end up with quite the predicament

Either the model has to fundamentally change or it will collapse by itself... either way it seems enough to speak about "the end of the world as we know it". -

Should and can we stop economic growth?From a societal and psychological/epistemic point of view, the problem is we have been living exclusively on the sharp end of the hockey-stick.

Our experiences, and the socio-economic structures we build thereupon, are literally fully contained within the couple of centuries that are the exception.

We are geared to expect the future to resemble the past, but have no real right to it dixit Hume. In most cases that kind of wiring has served us well... in this case maybe it won't? -

Should and can we stop economic growth?

GDP tracks energy consumption.

Rise in energy consumption has mainly been a rise in fossil fuels.

The idea that fossil fuels can - for intents and purposes of the kind of economy we have - just be replaced by renewables seem wishful thinking at best.

Ergo, If we want/have to cut out fossil fuels, GDP will decline... one way or another. -

Should and can we stop economic growth?

No, that would be pretty weird :-).I hope you haven't been waiting 3 years for this factoid; — Bitter Crank

Now and then I look back at some of my older posts, and I've been thinking a lot about this particular topic lately.... I changed my mind a lot since then.

I just came across it again. After the dust settled from the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and following for several hundred years, the economic growth rate was about 1/100th of a percent per year. Super stable. No growth. Once every century you could expect a 1% raise.

The so called "dark ages" during which the rate of growth was practically zero, wasn't 'dark'. The period saw some development, some innovations, improvements in agriculture, and so forth. But economic growth was very slow; the economy was a 'stable steady state'. — Bitter Crank

Yes, Growth is increase in GDProduct,

Product is the result of rearranging earths materials,

and rearranging can only happen by using energy.

Growth and energy-usage track almost linearly, which is why you see very low growth before the industrial revolution. You had wind and hydro, and solar via plants/food that powered humans and domesticated animals. That equation didn't change all that much for millennia.

It's often thought that what was the driver or the key for the industrial revolution, was the scientific method, or innovation. And while there's some truth to that (we needed those innovations), what really made it take off, was the fact that it unlocked fossil fuels.

That enabled us to multiply our energy output by a factor of 200 or something ridicules like that, which in turn enabled us to power all those machines, which in turn enable us to produce all those products... the rest is history.

I can't think of a tolerable method of achieving stable zero-growth. Global warming might do it for us, by reducing the population, wiping out the technological knowledge base, and focussing our minds on the matter of bare survival. The survivors would experience one grand RE-SET. Quite possibly, after the dust settled, life would go on in a stable, no-growth fashion for a long time. — Bitter Crank

Global warming might do it, or less energy might do it also... which would mean that no-growth (or even decrease) is not only a possibility, but an inevitability, if the reasoning about energy is on point here.

But yes, the real question is in what way, how will we get from here to there? At what energy level will we have to plateau? -

Should and can we stop economic growth?There's uncertainty about a number of things, when, how much, etc... but one thing seems clear, keeping our economy running on an expectation of growth seems like a recipe for disaster.

— ChatteringMonkey

One can expect growth all the time, but not in all industries or aspects of societies. — Caldwell

I was thinking about aggregate growth, GDP... but sure, presumably you could shift available energy from one sector to another. -

Should and can we stop economic growth?What do you think? — ChatteringMonkey

The way the question is formulated assumes that perpetual growth is a possibility. Since economic growth is intimately linked with energy-usage, in theory and in the long term that is clearly false... if we believe there are no exceptions to the conservation-laws that is. Energy is limited, so is economic growth.

In practice it's even worse, since we were able to temporally prop up our economies with the earths fossil fuels, which are for all our intents and purposes a one-time deal. As stocks of fossil fuels are rapidly depleting (or we have to stop using them because things like climate change), available energy will decline, and so will economies.

This is not a matter of choice, but a consequence of the laws of physics.... economies will eventually stop growing because of a lack of energy.

If we take that as a given, the more interesting question is what should we be doing to anticipate that inevitability? There's uncertainty about a number of things, when, how much, etc... but one thing seems clear, keeping our economy running on an expectation of growth seems like a recipe for disaster.

Yes, I think this is the problem. Continuous-growth economics cannot work in a system with finite resources. Like our Earth, for example. For years I have been amazed that this is not a phrase on everyone's lips. It is the reason for nearly everything we humans have got wrong in our treatment of our world. IMO, of course. :wink: — Pattern-chaser

Exactly. Growth-economics seems to only really apply in this small period in a planets history wherein resources seem practically unlimited because populations are still small relative to the amount of resources. -

Happiness in the face of philosophical pessimism?I make good money and can afford to do what I like, but there’s nothing I want. Anyway, I’m posting here because I’m hoping to get input from people who have been in a similar position and found some resolution. — Nicholas Mihaila

Usually the solution to this type nihilism involves seeing yourself more as part of a greater whole, that consequentially has a function or purpose in that larger whole.... Problem is we don't especially live in a culture right now that is conductive to this kind of solution, because any type of communitarian feeling be it religious or non-religious has essentially been hollowed out by individualism/capitalism/consumerism.

Anyway this is maybe not so much a resolution, but more of a recognition that you're not alone i guess. -

Realities and the Discourse of the European Migrant Problem - A bigger Problem?I think that it is dangerous if in a democracy real issues aren't openly discussed and rhetoric not adhered to facts and reality but to public sentiment and feelings takes over. In a way, that "dumbing down" of a political debate is a way of control. When political debate becomes a shit show, a distraction, somebody still has to make the actual decisions.

What do you think? Is this a serious problem or am I exaggerating? — ssu

No I think you're right... more generally, I think social media has made most politicians scared of doing anything that might cause something like a social media storm. The ones that aren't scared are the ones that have nothing to lose or those that make a career out of controversy anyway. -

What gives life value?Surely its value is mostly in the experience of life and not the relative span of time? — TiredThinker

Value is a more abstract notion of something we want essentially.

'Something "we" want' already implies a living thing and a duration of time.

For the purpose of this discussion (about meaning) you could say that life is that which has separated itself from the rest of the world (via a cell membrane) and tries to maintain itself, its form, over time.

So to answer your question, life gives itself values by trying to sustain itself over time. It doesn't make much sense to speak of value without both "experience ( a living thing)" and a duration of time. Theoretically, any duration of time could do. -

COP26 in GlasgowI read somewhere there is no limit to what can be done if you give others credit for it. And something about letting people think it was there idea. However, I think those tactics are old, foreseen and undermined by interests that want to conserve (ative) the status quo — James Riley

Maybe smarter people than me can figure it out. — James Riley

I agree, chances don't look that hot...I do think maybe the time is ripe for some kind of politician or political movement that can connect the dots in the right way considering how out of time and detached mainstream political parties are... there definitely seems to be a market for it.

ChatteringMonkey

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum