Comments

-

Do People Have Free Will?I experience, personally, a capacity to choose options at random. — Olivier5

Making truly random choices is notoriously difficult - ask a poker player. There are common situations in poker where random choices are considered to be an optimal strategy. Experienced players sometimes use props, such as a digital watch, to help them randomize their choices, because otherwise an opponent can pick up on a hidden bias and exploit it. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

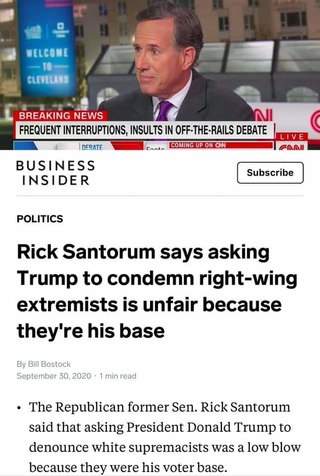

Santorum saying the quiet part loud. — StreetlightX

Lifeimitatesoutdoes The Onion.

Same day:

Stunned Pundits Criticize Trump For Refusing To Denounce His Base

CLEVELAND—After failing to condemn the group’s violent behavior and rhetoric during the first presidential debate, President Donald Trump came under fire from stunned political pundits Wednesday for refusing to denounce his base. “I’ve been reporting on these debates for decades, and frankly, I don’t know what the president was thinking when he declined to clearly and openly disavow thousands of violent, radicalized people who his reelection dearly depends on,” said ABC’s George Stephanopoulos, who, along with flabbergasted pundits from CNN, MSNBC, and CBS, noted that the president had several opportunities to distance himself from the people upon which his entire image, campaign, and presidency relied, and yet ignored them all. “How can Trump, as the sitting president, get away with this type of behavior that he’s totally normalized at every turn? It really shouldn’t be that hard for him to look at the camera, say their names, and then denounce his stalwart supporters whose votes are crucial for an election victory.” At press time, political pundits blasted Democratic candidate Joe Biden for refusing to explicitly denounce the extreme pro-Green New Deal rhetoric on the left. — The Onion, Wednesday 12:35PM -

Stove's Gem and Free WillYeah, he doesn't actually define responsibility, except in a negative way, so this was a bit of extrapolation on my part. I suppose if Strawson was a theist, then he would have to say that God is the only one responsible. Since he is not, his conclusion literally is: The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility.

Rather, we'd work out what it is we still mean by 'responsible' despite determinism. — Isaac

That would be a very different approach indeed (and one that I would endorse): start from the commonsense assumption that there is such a thing as moral responsibility, then work out what it is. Strawson, on the contrary, comes with presuppositions of what moral responsibility is, or rather what it cannot be, and then asks whether we can have it. -

Stove's Gem and Free WillThere is something that Strawson is saying with his argument. He apparently believes that the only thing that can bear the "ultimate" responsibility is that which is itself uncaused (but not random/chancy). He considers a person in that role and concludes that the role doesn't fit, because a person is just a transient state in the causal chain. This is an argument, though perhaps not a very good one.

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillThis is because for him the buck doesn't stop at the self. He doesn't actually give an account of personal identity, because it is irrelevant to his concept of will/responsibility. He only refers to 'one' as a shorthand indicating the person qua physical or mental state at some point of time, but he places that state in the middle of a causal chain and says that because of this middle position, it cannot bear the ultimate responsibility.

-

A thought on the Chinese room argumentWell, the neural network and the full connectome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans have been fully mapped. Simulating this neural network produces an identical response to different experiments when compared to a biological worm. If we are able to do this for our own brains we can expect similar results. But C. legans has only 302 neurons, orders of magnitude less than humans and the network complexity doesnot even come close. However, it is possible and hopefully we will be able to achieve this. — debd

Sure, but can this technology scale up many orders of magnitude to simulate human brain? And just as importantly, is such a neural net simulation fully adequate? It may reproduce some behavior, modulo time scaling factor, but not so as to make the simulation indistinguishable from the real thing - both from outside and from inside (of course, the latter would be difficult if not impossible to check).

I am not committed to this view though - just staking out a possibility. -

A thought on the Chinese room argumentI wonder if functionalism with respect to the mind in general might fail for a similarly banal reason? Might we be overly optimistic in assuming that we can always replicate the mind's (supposed) functional architecture in some technology other than the wetware that we actually possess? What if this wetware is as good as one can do in this universe? We might be able to do better in particular tasks - indeed, we already do with computers that perform many tasks much better than people can do in their heads. But, even setting aside the qualia controversy, it is a fact that nothing presently comes close to replicating the mind's function just as it is in actual humans, in all its noisy, messy reality. What if it can't even be done, other than the usual way?

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Trump's taxes and business ventures: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/podcasts/the-daily/donald-trump-taxes-investigation.html

We’ve now looked at almost 30 or 40 years of Donald Trump’s tax returns and his financial records, analyzed his inheritance. This wellspring that came from “The Apprentice” — that’s an amount of income unlike anything he experienced in any other aspect of his life.

It sounds like a big thing you’re learning is that when it comes to the kinds of deals in which somebody else borrows the Trump name and uses it, Donald Trump is swimming in money, but when it comes to a business that he buys and tries to operate, like a big golf course, those become big financial black holes.

The less decision-making authority Donald Trump has on a business, the more money that business is going to make. And the more he’s involved in designing a business, setting it up and creating a business plan, the more likely it is to have trouble. — NYT -

Stove's Gem and Free WillIn a way, Strawson's argument is the opposite of the Gem: instead of "My will is my will, therefore..." it is "My will is not my will, therefore I am not responsible." Which would actually be reasonable, if he could give a convincing argument. And his argument isn't all bad, but it is too limited and oblivious to reality.

-

Stove's Gem and Free WillThere is something analogous here, but I wouldn't say it's the same thing. Strawson capitalizes on the so-called sourcehood criterion of free will: for a decision to be free, it has to be your decision, you have to be its originator. This is fair, generally speaking; there isn't an inherent fallacy in this criterion (unlike in Stove's Worst Argument). Sociological research shows that this criterion indeed forms part of what people commonly mean by "free will," and philosophers too usually give it its due.

Where Strawson's argument can be criticized is in how he caches out this sourcehood. Strawson in effect identifies sourcehood with causality. His theses is that in order for you to be responsible for your decision, you have to be its ultimate causal source. He then argues that since you are just an intermediate element in the causal chain (this isn't exactly his argument, but it can be restated this way), then you cannot be ultimately responsible.

This identification of responsibility with causality is, again, not entirely unreasonable. What I think makes Strawson's argument bad, and not just flawed or mistaken, is that he takes this framing of sourcehood for granted, without any reflection and argument (at least that was my impression from his oft-cited paper The Impossibility of Moral Responsibility). This also characterizes most free will discussions on the 'net (including this very thread), where people plunge into arguments without bothering to do any philosophical groundwork, without asking questions that need to be asked, and often just talk past each other. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?For my part, I am not really paying attention to this pompous ass, but there is not reason why we can't discuss analytical philosophy or the value of philosophy.

-

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?I take your point that as any pursuit that depends largely on public support, philosophy has a burden of justifying its existence. But as I think you agree, this question should not be considered transactionally, but in the wider context of the value of learning. (After all, philosophy is not much different in this respect from many of our other pursuits, and not only academic.)

But I want to stress that value here does not have to be a measurable material value. We don't support philosophy in the hopes of possibly getting Velcro or strong encryption out of it somewhere down the road. This is value in a broader axiological sense. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?I feel bad sometimes for studying philosophy. Other fields are focusing on actual problems like how to stop COVID or how to help countries with serious economic problems while philosophers shut them selves off from the outside world to go play in their own heads or provide extensive commentary on a long dead philosopher that no one cares to read and often requires a second language to fully understand. — BitconnectCarlos

Well, this is true for a lot of academic disciplines, both in humanities and in physical sciences.

One has to wonder about the complicity of this middle-management demand for 'value'. — StreetlightX

Exactly. This demand for (whatever) philosophy to justify itself in terms of its measurable value to society ought to be resisted. -

Gotcha!I think (as you correctly point out) it's all about motivation. If your immediate response to a new idea is, that you are obviously right and there's no value to that new idea, then it's very easy to point out irrelevant contradictory technicalities or to even willfully misunderstand the proponent. — Hirnstoff

Likewise, if your response to any push-back is that you are obviously right and there's no value to a different view, then it is very easy to come up with ad hominem excuses for why the opponent can be dismissed outright. For example, psychoanalyze them and conclude that the only reason they are contradicting you is that they are "craving the Gotcha Game experience." After that you don't have to listen to anything they say and you can still feel good and smug. -

Are we justified in believing in unconsciousness?Should we only believe in what is verifiable? — petrichor

Obviously not. Most of the things that we hold as true are not verifiable in practice or even in theory.

How would we know? — petrichor

If you were consistent in your skepticism, you would eventually arrive at solipsism, thus undermining all your empirical reasoning up to that point. This is a dead end. -

A thought on the Chinese room argumentAnother issue is that the contents of a computer's mind (if it has one) are immune from discovery using scientific methods. The only access to knowledge of computer mental states would be through first-person computer accounts, the reliability of which would be impossible to verify. Whether machines are conscious will forever be a mystery. This suggests that consciousness is unlike all other physical properties. — RogueAI

How is this issue different from not having a first-person experience of another person's consciousness? Unless your real issue is that it's a computer rather than a person - but that is the same issue that Chinese Room-type thought experiments try to capitalize on (confusingly, in my opinion). -

A thought on the Chinese room argumentIn A nice derangement of epitaphs Davidson argues that language is not algorithmic.

Searle is arguing much the same thing with the Chinese room. — Banno

I think Searle's thought experiment was rather a reaction to reductive takes on consciousness, particularly computational, functionalist ones:

I think that consciousness or understanding or perception at a particular point of time is the function of the structural and physiological state of the neuronal network at that point in time. — debd

Now consider the room to be our brain and the person is replaced by a chain of neurons. — debd

There are other variants of the thought experiment that are an even better fit for this, such as Ned Block's Chinese Nation thought experiment, where a large group of people performs a neural network computation simply by calling a list of phone numbers. The counterintuitive result here is that a functionalist would have to say that the entire system thinks, understands language, feels pain, etc. - whatever it is that it is functionally simulating - even though it is very hard to conceive of e.g. the Chinese nation as a single conscious entity.

But I think this people-as-computer-parts gimmick is a red herring. Of course a part of a system is not equivalent to the entire system - that was never in contention. A wheel spoke is not a bicycle either. The real contention here is whether something that is not a person - a computer, for example - can have a functional equivalent of consciousness. -

Can research into paranormal be legitimized?Whenever I hear about those that study psychics, telepathy, remote viewing, and the like it is usually some specialized group that studies nothing else — TiredThinker

Well, that is generally true of specialists. You will find the same with black holes or medieval French literature.

But as for your general question, there has been a fair bit of non-crank research into some areas with paranormal associations, such as near-death experiences. It depends on the character of the claim, how conducive it is to scientific study. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?Analytic philosophy, I think, hasn't really been a thing for some time now. — Srap Tasmaner

Was it ever a thing? Is "analytic philosophy" a meaningful and useful designation? I think philosophers tend to answer in the negative. (And the same with "continental philosophy.") -

Is Logic Empirical?If conjunction and disjunction (∨ and ∧) are interpreted differently than in classical logic, then it does not seem so surprising that the principle of distributivity might fail. But this does not entail that the principle does not hold universally. The principle does hold universally (it seems to me) so long as we interpret the conjunction and and disjunction symbols (and whatever other symbols might also be relevant) to mean what they mean in classical logic. If we change their meanings, then it makes (classically) logical sense that we'd get a different set of theorems. — Dusty of Sky

If you identify logic with classical logic, or something with a close family resemblance, then yes. But formal logic in general is less specific than classical logic, even though it still has to do with reasoning, with inference. Which is to say that the patterns of reasoning that are available to us go beyond those that are covered by classical logic. With this general sense of logic, it is indeed possible to have a logic in which conjunction and disjunction mean something different than what they mean in classical logic, but play broadly similar roles. Perhaps the example on pp. 12-13 will help to illustrate the point, though admittedly, taken in isolation it may not look very convincing.

But I admit that much of what I read in the introduction went over my head. — Dusty of Sky

Yeah, I am out of my depth here as well. Perhaps one of our resident mathematicians will come along and enlighten us :) -

Is Logic Empirical?I think you make a good point here:

It seems arbitrary to me that we should make the realist assumption that (A1 or A2) is true, even though this assumptions can't be empirically verified, but not also assume that the principle of distributivity holds just because we can't empirically verify either (A1 and R) or (A2 and R). — Dusty of Sky

But this is if you look at quantum logic as making an absolute metaphysical statement about quantum mechanics, rather than simply treating the logic instrumentally, or as usefully capturing some aspect of the phenomenon without pretending to the ultimate truth.

My claim is that a logic in which the principle of distributivity is false does violate the laws of thought such that any claim made in such a logic, regardless of its usefulness, amounts to nonsense if we actually try to conceive of its meaning. — Dusty of Sky

Logic without distributivity is not as problematic as you think. You may find this recent article interesting: Non-distributive logics: from semantics to meaning. -

A Philosophy Of SpaceAnd of course there's heaps from the philosophy of physics side. Reviews and anthologies alone will probably fill a shelf or three, e.g. Tim Maudlin's entry on Space and Time in Prinston Foundations series, Dieks' The Ontology of Spacetime, etc.

-

A Philosophy Of SpaceOne wonders whether a focus on things is a form of bias which obstructs our view of reality. As example, astronomers seem to spend most of their time focused on things in space, instead of space itself. To the degree this is true, they are focused on tiny details instead of the big picture, a cosmos dominated by space. — Hippyhead

Rather than speculate in the abstract, do yourself a favor and google "philosophy of space." You'd be surprised at what scientists and philosophers have gotten up to in the last 300 years or so. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticRight, I am just saying that bringing up the fact that a conscious being is always involved in QM experiments as a last-ditch defense of a mentalist thesis is futile, because the same is true of everything that we do. So one is no more justified in making the inference in case of QM than in any other case (e.g. performing a classical physics experiment, or getting beer from the fridge).

Who has represented himself as a purely mentalist interpreter? — Mww

Well, Wigner (who came up with Wigner's Friend thought experiment) was one famous proponent who has been mentioned here. von Neumann was another before him. Both were big names in mathematics and theoretical physics, especially Neumann, so one doesn't dismiss them lightly. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticYou are talking about the mind interpreting the world. Mentalist interpretations of QM imply the mind directly affecting the world, e.g. reaching out and collapsing the wavefunction.

-

All mind, All matter, DualisticOh, you want boobies? Why didn't you just say so? :)

Anyway, to your point that an experimenter has to be involved, that's true of literally everything, ever, even when we are not talking about scientific experiments. You cannot come to know something without your mind being involved in the process one way or another. But why then make it a special point about quantum mechanics? -

Is Logic Empirical?Even if we treat it as false in quantum mechanics, I don't think we must interpret this as invalidating the principle's universality. — Dusty of Sky

You don't have to use quantum logic in quantum mechanics either; classical logic works perfectly well there - it's just one way of thinking about QM that some find useful or entertaining. Which goes to show that "laws of thought" - including the principle of distributivity - don't have to be as rigid and universal as people often assume. We can adopt different logics for different uses. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticNow I'm interested in how this would hold up. In the example given, even before the mind cognates the "true" state, it had already been decided by the measurement devices placed. If a measurement device measures which slit the electron goes through, and we NEVER get a case of a striped pattern, isn't it safe to assume that the measurement is what collapsed the wave function not us? If it were us we should get a striped pattern. — khaled

Right, that would be the orthodox Copenhagen interpretation: the electron interacts with the detector and the wavefunction collapses from a superposition of two states into a single pure state right at that moment, way before anyone conscious can come to know about what happened.

The Everett (Many Worlds) interpretation does away with the wavefunction collapse, so that the superposition persists, but now the two states are effectively independent and non-interacting - decohered. If you would like to play along with the mind collapse theory, this parallel-world state would allow you to stall for as long as it takes a person to read off the result from the paper - only there are now effectively two persons, one in each of the two decohered branches of the wavefunction. One of the two, the ensouled one, then collapses the other branch of the wavefunction, together with her mirror twin, and the sanity is restored.

I am just making shit up here, as you've probably guessed. I don't know how the actual proponents of mentalist interpretations deal with decoherence, and can't be bothered to look it up, to be honest, because I don't take this very seriously. But if you are interested, the information must be out there. I'd wager that a deft and committed theoretician can come up with a robust enough interpretation - if you can swallow the metaphysics. It is ultimately a matter of taste. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticWigner was roundly refuted by everyone including himself, including for the above reasons: necessitating consciousness for wavefunction collapse cannot reproduce statistical experimental outcomes. — Kenosha Kid

It can, with some footwork, but at the cost of metaphysical extravagance. But then mind/matter dualism is already pretty extravagant, and if you've already payed that price, then Wigner comes at little additional cost.

I think it might have been him that also pointed out that conscious observers are high-temperature bodies and cannot mediate coherent superpositions. — Kenosha Kid

So like I said, you have to go with Everett up to a point, assuming that decohered states continue to exist side by side until the mind cognates the "true" state, at which point the "counterfactual" state (along with the counterfactual observer's body!) vanishes. Or something like that. Heady stuff, but so is dualism. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticWhat @khaled attributes (inexplicably) to the Copenhagen interpretation sounds like the von Neumann-Wigner interpretation, in which only minds have the power to collapse the wavefunction. If my understanding is correct, the interpretation would say that in the double slit experiment the system (along with the portion of the world that interacts with it) remains in a superposition right until the moment when a conscious being observes the result, at which point the "counterfactual" branch of the wavefunction vanishes. Without that vanishing act, this would be the same as the Everett interpretation. Indeed, before conscious minds entered the world, the world was entirely Everettian. (Either that, or God was extremely busy, collapsing wavefunctions right and left!)

-

All mind, All matter, DualisticThe Copenhagen wavefunction is a mathematical encoding of what we know. If what we know about the past changes, that change is encoded in the past, not at the moment of discovering the change. — Kenosha Kid

That is what I mean when I said that it makes the mind necessary for matter to be definite — khaled

That doesn't follow. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticAs far as I know that is exactly what it suggests. The uncollapsed "result" is measured by a measuring system — khaled

Which is when the collapse allegedly occurs: when the (classical) measuring system interacts with the quantum system to produce a measurement. Measurement here is a technical (and quite contentious) term; it should not be interpreted by appealing to its common meaning outside of QM.

Some of the original proponents of the so-called Copenhagen interpretation also favored mentalist takes on QM, but what most physicists nowadays take to be the Copenhagen interpretation has nothing to do with mentalism. -

Knowledge of Good and EvilThe Garden of Eden is one of the most misunderstood passages in the history of the Bible. — bcccampello

This is theology, not general philosophy. Wrong forum. -

All mind, All matter, DualisticAfter quantum mechanics many scientists now do not know what to make of mind. — khaled

This is not accurate. There are interpretations of quantum mechanics that involve the mind (e.g. Neumann–Wigner), but as Kenosha Kid says, the Copenhagen interpretation is not it, nor are its main competitors. Mentalist interpretations of QM are pretty far from the mainstream. -

Indirect and contributory causationThanks for your candid explanation. As I suspected, what is at issue here is not the original question, which is easy enough to answer, but how you frame the question in the first place. The key contention here is empirical, not logical. The therapist thinks that the illness is the main reason for the persisting symptoms, with the implication that treating the illness would alleviate the symptoms. Your position is that the symptoms would likely persist with or without the illness, with the implication that the proposed treatment probably would not address the problem. (On a personal note, this situation is familiar to me, and probably to many others as well; even now I am in a similar situation of having to decide on a course of treatment, having consulted with a specialist.)

Unfortunately, this contention is not something that a formal logical analysis could resolve. Everything hinges on the two contrary judgements regarding "the facts about the world," as you put it. -

Philosophy....Without certainty, what does probability even contribute?:up: Welcome to the forum!

-

CoronavirusThe 2020 IgNobels are in.

MEDICAL EDUCATION PRIZE [BRAZIL, UK, INDIA, MEXICO, BELARUS, USA, TURKEY, RUSSIA, TURKMENISTAN]

Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, Boris Johnson of the United Kingdom, Narendra Modi of India, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, Donald Trump of the USA, Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, Vladimir Putin of Russia, and Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow of Turkmenistan, for using the Covid-19 viral pandemic to teach the world that politicians can have a more immediate effect on life and death than scientists and doctors can.

REFERENCE: Numerous news reports. — Improbable Research -

Is anyone here a moral objectivist?You seem to be using the forum as a personal blog or scratchpad. There are better platforms for this. The point of posting on a forum is conversation. I don't know what your purpose here is, but seeing that you apparently aren't interested in engagement, I am no longer reading your posts. No offense, but if I just wanted to read something, there are thousands of things I would rather read than your musings (indeed, I am reading some interesting papers right now.)

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum