Comments

-

In praise of anarchyAs I wrote previously, if what you propose hasn't ever happened, won't ever happen, can't ever happen, then your idea is a fantasy. Meaningless. If you can't see that or show me how anarchy might work, then we'll never come to any resolution. That's my best shot. — T Clark

Ought implies can. The idea that all forms of government are unjust must be rejected until it can be shown (against all available evidence) that the alternative is possible in a society larger than a modern-day commune. Even then it would likely come down to choosing one injustice over another, because there is no rule that rejecting one form of injustice leaves you with a (more) just state of affairs.

No, they did have rights and those rights were not respected. I am not sure I can argue with someone who thinks a person has a right if and only if the government of any community of which they are a member says they do. That view is so plainly false to me that I am at a loss to know how to argue with someone who is willing to embrace its implications. — Clearbury

I am not sure you can, either - at least you have not demonstrated such an ability. Saying that your opponent is obviously wrong and leaving it at that is a conversation-ender. -

All Causation is IndirectWhy should this be the case? I drop an object from a certain height and predict when it will hit the ground. How does this eliminate causality? There are a host of factors involved in this physical feat, and one can argue one's way through that jungle, rather than citing a principle cause, gravity. — jgill

That sort of cause fits with the conventional contemporary ideas of causation, what @Count Timothy von Icarus refers to as granular efficient causation: gravity is the cause of the object dropping to the ground, or, alternatively, your releasing it from your grasp is the cause. No argument from me here, other than what has already been noted about such causation being in part subjective.

(I wrote a math note a year or so ago that partitioned a causal chain temporally so that each link was formed by a collection of contributory causal effects added together to produce one complex number associated with that link. Just a mathematical diversion, but a vacation from the plethora of philosophical commentaries about the subject.) — jgill

But here I would question whether the notion of cause adds anything that is not already given in the mechanistic description. -

Visualization/Understanding or Obscurantist Elitism?I think you overstate the limitations of our conceptual grasp. We are not locked into a fixed Kantian conceptual universe. Our minds have some flexibility and room for development, enabling us to comprehend formerly incomprehensible (or at least convince ourselves that we do so comprehend). Galilean principles of motion were once unthinkable, as it seemed obvious to everyone that motion must be sustained by a motive force, and there had to be a categorical difference between motion and rest. But we have learned to get over this conceptual hurdle (even though our folk physics is still more Aristotelian than Galilean). Newton's spooky action at a distance (setting aside further developments in General Relativity) also doesn't seem to be causing as much consternation as it did in his day. In general, people working in their fields, be it fundamental physics, genetics or linguistics, develop conceptual tools that enable them to apprehend even complex and unintuitive ideas, at least to some degree.

-

Visualization/Understanding or Obscurantist Elitism?Its not something that can go away and its saddening that logical positivists along with their ilk had buried it for so long under dense logical axiomatic formulations of theories (syntactic understanding of theorizing) or mathematical abstraction (semantic understanding of theories) in a sisyphean attempt to grasp natures objectivity by removing us along with understanding/explanation as well. I.E. the ten cent phrase that, "Science ONLY deals with description and not with explanation." — substantivalism

Struggles with interpreting new and unintuitive science are not that new. Neither is the retreat to the "shut up and calculate" quietist approach. Newton wrestled with the philosophical implications of his theory of gravitation all the way, and never reached a satisfactory conclusion. After the publication of his Principia, he wrote in a letter to Richard Bentle:

It is inconceivable that inanimate brute matter should, without the mediation of something else, which is not material, operate upon, and affect other matter without mutual contact; as it must do, if gravitation, in the sense of Epicurus, be essential and inherent in it. And this is the reason why I desired you would not ascribe innate gravity to me. That gravity should be innate, inherent, and essential to matter, so that one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum, without the mediation of anything else, by and through which their action and force may be conveyed from one to another, is to me so great an absurdity, that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it. Gravity must be caused by an agent acting constantly according to certain laws; but whether this agent be material or immaterial, I have left to the consideration of my readers.

In the Principia he hedges, saying that his theory is merely mathematical, cautioning even against treating it as physics:

I now go on to set forth the motion of bodies that attract one another, considering centripetal forces as attractions, although perhaps - if we speak in the language of physics - they might more truly be called impulses. For we are here concerned with mathematics; and therefore, putting aside any debates concerning physics, we are using familiar language so as to be more easily understood by mathematical readers.

Hitherto we have explained the phenomena of the heavens and of our sea by the power of gravity, but have not yet assigned the cause of this power... I have not been able to discover the cause of those properties of gravity from phenomena, and I frame no hypotheses; for whatever is not deduced from the phenomena is to be called an hypothesis; and hypotheses, whether metaphysical or physical, whether of occult qualities or mechanical, have no place in experimental philosophy... To us it is enough that gravity does really exist, and acts according to the laws which we have explained, and abundantly serves to account for all the motions of the celestial bodies, and of our sea.

(The latter passage, with its famous famous hypotheses non fingo, was added in the second edition.)

Newton did entertain a number of hypotheses (speculations), mostly towards the immaterial or divine, but he was too scrupulous to present them as scholarly conclusions (and he didn't miss a chance to contrast himself with some of his rivals in that respect - notably, Leibniz with his vortices). -

All Causation is IndirectI put "physical laws" in scare quotes because many physical laws are simply close approximations of behavior. For instance, Newtons Laws are "good enough," but won't work even on the macro scale with multi-body problems. Nancy Cartwright's work on this would be the big example I can think of. Laws are symmetric because that's how the math used to describe them works, but nature doesn't necessarily correspond to such laws. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The sciences with their laws represent our best understanding of nature. Our understanding can be wrong, of course (though not very wrong, as we previously discussed), but in that case, we can have no basis for knowing in what way it is wrong. There can be no basis for asserting that our laws may say this, but in actuality, nature is that.

I say physics isn't time symmetric because there are several observed time asymmetries in physics, at both the smallest and the largest scales. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, I still say that "physics is time symmetric" isn't very meaningful, because physics is not one theory but many.

This tangent started from the thesis that causation does not sit comfortably with modern science - physics in particular, but not just physics. One of the issues with causation is that the asymmetry between cause and effect (causes always precede their effects) is often lacking in the shape of scientific laws, so that the asymmetry becomes an added anthropocentric postulate (though easily explainable in those terms). This issue is not nullified by the fact that some processes are time-asymmetric, because the use of causal language is not limited to just those processes.

Arguing for time symmetry against all empirical evidence (no one has ever observed time running in anything but one direction, nor has anyone ever observed the defining elements of quantum mechanics, decoherence and collapse, running backwards, making for a very distinct observable asymmetry) seems to largely rely on the fact that the very mathematics used for descriptions assumes a sort of eternalism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think eternalism is a red herring here (indeed, I am not sure the concept is even meaningful). Whatever your stance on the "existence" of past and future events and entities or on the special ontological status of past, present and future, it can still be unclear from the purely objective analysis of relationships revealed through science why causes must precede effects, unless that is simply baked into their definition.

Russell famously cautioned that "[t]he method of 'postulating' what we want has many advantages; they are the same as the advantages of theft over honest toil." One peril of postulating metaphysical principles not found through honest scientific analysis is that they can stifle scientific thought. One curious example of such thought that is seemingly at odds with orthodox causality is the Transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics, which involves an absorber sending a retarded (going back in time) "confirmation wave" to an emitter. (This QM interpretation was actually an extension of a time-symmetric interpretation of classical electrodynamics proposed earlier by Wheeler and Feynman.) I am not a proponent of the Transactional interpretation as such, but I think that it has the right to exist for the possibility of enriching our understanding.

As to the problem of disentangling causes, I think this is a problem that only results if one takes a very narrow view of causality as a sort of granular efficient causation. But what we are most interested in causes are general/generating principles, not the infinite (or practically infinite) number of efficient causes at work in any event. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Well, yes, granular efficient causation is basically what causation has been about in recent times (the past 200 years or more). You seem to want to dilute the concept so as to include just about any kind of mechanistic analysis, which is tantamount to eliminating causation. -

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismWell, for one thing, you have "physical" all over the place. That's no clearer than "physicalism."

-

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismWhat are we to say of it then? The suitcase serves a function but often in an indirect way. Maybe many know it's empty or don’t know what’s in the suitcase, but just so long as you have a suitcase! But then, to avoid hypocrisy, the door should be open to alternative metaphysical commitments that don’t have any direct bearing on the conducting of the scientific method, no? Except those who take that route seem to get a much harder time of it---socially.

I suppose I am advocating for a kind of radical agnosticism as to the ultimate nature of things because I think language won’t take us anywhere near there and we end up creating word games that unnecessarily divide and polarise. — Baden

Being open-minded is a virtue, and most reasonable people, whether physicalists or otherwise, would say that they are - in principle - open to alternative metaphysical commitments. Open-mindedness is not the same as agnosticism, though. One can have strong opinions, yet be open to changing them.

The main issue with physicalism, as with many other broad philosophical and ideological categorizations, is that it is hard to define and articulate with any precision and consistency, while avoiding circularity. I think the best we can do with it is to treat it ethnographically, characterizing it by the sort of philosophical views that self-identified physicalists tend to hold in common. You will generally find a preference for empirical epistemology and scientific method, and non-mentalist ontology. -

All Causation is IndirectNot all. The evolution of entropy in a closed system is deterministic (entropy always increases), but it is not time-symmetric because entropy decreases in reverse time. — jgill

A closed system can evolve through a complete cycle and end up in the same state with the same entropy, as long as there are no irreversible energy exchanges within the system.

Of course, real macroscopic systems are never closed.

There are mathematical dynamical systems that function in simple ways that are not reversible. f(z)=z^2. — jgill

Of course. Moreover, even Newtonian mechanics admits of indeterministic edge cases, but they are artificial and of no practical significance. -

The Empty Suitcase: Physicalism vs Methodological NaturalismThe metaphor of the empty suitcase aptly characterizes common criticisms of physicalism and materialism: they tend to load these terms with whatever baggage their authors consider to be vulnerable to attack.

Like saddling physicalism with a commitment to determinism, for example. (OK, that's not quite fair, because this is not central to your criticism, and besides, this is so blatantly false as to be hardly worth focusing on.)

The whole point of physicalism being "unscientific" (i.e., not being entailed by science) misses the mark. If physicalism is a metaphysical position, as you (and most everyone else) characterize it, then its only obligation to science is to be consistent with it and to not give it a priori constraints.

Anyway, I am not here to defend physicalism: I am not attached to such vague labels. I prefer discussing more specific positions. If I ever identify as a physicalist, it is for sociological reasons: often enough, I find myself attracted to positions held by thinkers who identify as, or are identified as physicalists. -

All Causation is IndirectWhich symmetries? Physics is time asymmetric at both the macro and micro scale, although there are time symmetric processes and "laws." Time is obviously asymmetrical in a big way at the global scale, and depending on how one views quantum foundations it is asymmetric in another way: collapse/decoherence occurs in only one direction. The latter can be interpreted in many ways though. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I am not sure what you mean by "physics is time asymmetric." There are different physical laws (why the scare quotes?), many of which are time-symmetric or atemporal (such as statics and variational mechanics). All deterministic processes are time-symmetric, and some indeterministic as well (in the sense that probabilistic dynamics is time-symmetric). Thermodynamic processes are, of course, irreversible on the macro-scale. But enough of physics and other sciences challenge traditional causal notions to merit mention. I mean, you can't just wave away the whole of classical mechanics, for one thing.

But as regards to the original point of departure for this conversation (causation as storytelling), the more relevant challenge for the objectivity of causation is that, when we study nature, we cannot identify the sort of causes that we are usually looking for without subjective guidance - starting from the very choice of framework (scientific or informal), and then picking from the potential overabundance of connections between events and things those that are important to us. -

Currently ReadingIt perfectly aligns with the stereotype of Russian literature so often thrown around by people who have read none of it (or have read one or two Dostoevsky novels and feel qualified to speak about the rest). — Jamal

Dostoevsky can be quite funny. Acerbic, yes, but also just plain funny. Take his Village of Stepanchikovo - his take on Tartuffe (and a dig at Gogol). A minor work, compared to his masterpieces, but a sheer comic delight.

In fact, Dead Souls is a comic novel, mostly bouncy and light in tone, not ponderous and depressing. — Jamal

Yeah, whoever picked that painting for the cover clearly had no idea what they were illustrating - just going off "bleak Russian novel" stereotype.

You make a good point. I never felt that War and Peace quite fit the mold of "Russian literature," either. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You know who is never funny? Tolstoy. Even the characters and situations that he satirizes just aren't funny. Not that you necessarily miss it in his writing - there's plenty there, even without funny-ha-ha.

The Obscene Bird of Night by Jose Donoso — SophistiCat

Looks interesting. How is it? — Jamal

I like it, so far (I am a slow reader, so bear with me). It's not a crowd-pleaser, but it's strangely engrossing. -

All Causation is IndirectCausal analysis maps neatly enough for us to cure many diseases, fly around the world, travel to space, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Causal analysis is pragmatically indispensable, to be sure. But pragmatics is tightly entangled with human concerns. The more one tries to objectify the story, the harder it becomes to tell in causal terms, because it then quickly collapses under the weight of metaphysically suspect ceteris paribus clauses and time-reversal symmetries that are antithetical to causation. Pragmatic considerations eliminate most of these difficulties: ceteris paribus clauses and time-reversal symmetries can simply be dismissed (or not even brought up in the first place) as pragmatically irrelevant.

The argument then is that causation, despite it pervading our thought and practice, is not an objective feature of the world at large, in which humans are but a speck. This is not quite right, though, because we as intelligent agents could not have succeeded in this world without having an essentially accurate understanding of it. What we can say then is that causality, like regression towards the mean, is at least a good heuristic. But there is no metaphysically fundamental "law of cause and effect."

When people say "smoking causes lung disease," they do not mean "anyone who smokes will necessarily develop lung disease." — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is actually a good example of how we extract pragmatic causality from a scientific result that does not display a clear, objective cause-effect relationship. What science shows is that smoking increases lifetime risk of lung cancer approximately tenfold. But that increase is from a fairly low base of about 0.1% for non-smokers. So, smoking takes the lifetime probability of the cancer event from ~0.1% to ~1%. Not something that would traditionally be identified as a cause - except for these pragmatic considerations: (1) the potential effect is hugely impactful to an individual, and (2) the putative cause is one of the few, if not the only factor that can be practically influenced by individual behavior and government policy.

And there is also, I think, an urge to begin the casual story with a human. The trigger does not pull itself, the gun does not aim itself. And one cannot follow the causal story into the physiology and neurology of the individual without generalising them out of existence. The story becomes personal and no longer objective. — unenlightened

I like the interventionist account of causation (X causes Y if we can wiggle X to waggle Y), which is inspired by and modeled in large part on our empirical practices. -

Currently ReadingI read The Invention of Morel earlier this year. It's great, and surprising in a way I can't reveal without spoiling the story. — Jamal

Cool. I am on a Latin American streak, currently reading The Obscene Bird of Night by Jose Donoso. Will look for this next. -

All Causation is IndirectIn most cases, sense experience is prior to the stories we tell (e.g. I would not say that airliners crashing into the Twin Towers is what caused them to fall had I not seen airliners crash into the Twin Towers). But if causes only exist in stories, then are our sense experiences uncaused, occuring as they do for "no reason at all?" Certainly they cannot have "causes" that are prior to our storytelling on this view. Nor could anything in nature have been caused prior to the emergence of language. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Let's not confuse sense and reference. The point is not that a cause is a frivolous concoction, but that it doesn't map neatly onto the sensible world - it depends in large part on the human perspective, perhaps more so than most theoretical entities and postulates in the sciences. -

All Causation is IndirectWhy are some stories useful and other ones not useful? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think you misunderstood the "useful story" talk. It doesn't mean making up whatever story you like. ("Fiction" isn't helpful here, though.) In any event, there are innumerable causal links connected to it, but the vast majority of them are not of any interest to us. We pick the ones that seem the most salient within a given narrative framework.

In a murder case, the detective is searching for the perpetrator who fired the gun, thus causing the victim's death. The ballistics expert wants to know the cause of the bullet's hitting the victim. The pathologist wants to know the medical cause of the victim's death. The prosecutor and the defender each present a different cause of the perpetrator causing the victim's death.

These are all useful causal stories, and each and every one of them can be true! At the same time, one can think of any number of causal stories that are not useful in a given context. Indeed, the story of how the bullet travelled from the barrel of a gun to the body of the victim is not very useful to the pathologist. Moreover, the vast majority of contributing causes in the past light cone of the murder event are not useful to anyone. -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”

Is this an impossible picture? -

Currently Reading:up: I first read it as a teenager in translation. Reread it this year, decades later. Barnes & Noble Classics annotated e-book.

-

All Causation is IndirectOne tells only the causal story that one finds interesting — unenlightened

Yes, that's the key to understanding causality. -

All Causation is IndirectIf all causation is indirect — I like sushi

Says who? Why? What is direct causation?

I couldn't make any sense of your OP - it reads as if it was ripped out of some ongoing discussion. Was this split from some other topic? -

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Agreed, the very idea of having someone else's experience seems to be incoherent. Perhaps it can be approached by atomizing experience into distinct qualia that could, hypothetically, be imbibed without completely relinquishing your core self. One could imagine, for example, a blind person having a visual experience that would otherwise be denied to them by their own faculties. But the closer you approach someone else's what-it-is-likeness, the less of your self you can retain.

-

Logical proof that the hard problem of consciousness is impossible to “solve”Just for the record, that isn't the standard way of stating the problem, and it isn't David Chalmers' way (he coined the phrase). You can listen to Chalmers describe it here: He defines the problem as "how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experiences in the mind." When we solve this problem (I do believe it's when, not if) we may or may not know "what it's like" to be someone else. That's a separate, though perhaps related, issue. — J

To know "what it's like" to be someone is to experience what they experience. Such experiential knowledge cannot be gained through propositional knowledge of how experience works. There is no mystery or paradox in this, of course, and as you note, this is not the "hard problem." -

Am I my body?I think that when we use phrases like "my body", it's mostly indexical, and doesn't ned to have much metaphysical import. A reference mechanism to this body, the one which is typing this post, is what "my body" is, regardless of how I otherwise conceive it. — fdrake

Agreed, "my" in "my body" is indexical and could be replaced with "this body" in the same context. It would still make sense to say "I have a body," meaning that a body is a part of me, rather than being some external possession of mine.

I think this is very true. There are plenty of ways that every person is which are not just bodily or minded, even though the body and mind are involved. Anything the body does is somehow more than the body, but the body is not just a substantive part of the act - the body is not a "substance" of walking.

The person may also be identified with a role they play, irrespective of their body's nature - a barista, a lawyer, a cook. It is the person which is those things, and not the body. — fdrake

By the same token, a person is bodily. Here "is" does not indicate identity, but rather serves to relate a predicate to the subject, as in "Socrates is a man."

I noticed that you have a strong interest in the work of Ayn Rand. — Joshs

what -

Am I my body?Welcome, and thanks for a thoughtful post. Not much to add or disagree with, but this is a bit clumsy:

I don't "have" a body, because to do so would require that I am separate from my body. I am not the car that I own. — Kurt Keefner

No, to have something doesn't necessarily imply that the something is separate from yourself - hence why we say things like "my body" - or, for that matter, "my mind." Yes, you are a whole person, with a body, and its various parts, and a mind, and its various aspects. -

Atheism about a necessary being entails a contradictionDo you want to explain why you think this? — Hallucinogen

(1) Existence is not a series (of anything)

(3) The universe does not have numbered "terms"

(5) Does not follow -

Atheism about a necessary being entails a contradictionIt's uncommon to see an argument with multiple premises, all of which are false.

-

An Objection to Kalam Cosmological Argumentanthropic selection — SophistiCat

What is that? — noAxioms

Anthropic Principle is a particular case of an observation selection effect. -

An Objection to Kalam Cosmological ArgumentHighly? No. Speculative, yes, but all cosmological origin ideas are. This one is the one and only counter to the fine tuning argument, the only known alternative to what actually IS a highly speculative (woo) argument. — noAxioms

I don't think the (theological) fine-tuning argument needs such a counter, because I don't believe it works. There is a related (and somewhat controversial) issue of "naturalness" of fundamental constants in cosmology, for which anthropic selection considerations might offer a valid solution. But perhaps all this is for another topic. -

Question about deletion of a discussionWell, it was stupid to begin with, and then Tarsky (aka @alcontali, I believe) took it to the next level.

-

Ukraine CrisisApparently Putin announced a few days ago that Russia is planning to change it's nuclear doctrine:

AP News: Putin lowers threshold of nuclear response

As various commentators have pointed out, the change is clearly intended to make the doctrine more vague. It's also pretty much a direct warning to not allow Ukraine to strike targets on Russian territory using western weapons.

This seems a fairly big step for Russia, which seems to indicate that they're really concerned about possible long range strikes. It also demonstrates the bargaining power Russia's nuclear capabilities still represent. — Echarmion

What's bizarre is that, according to Russia's official position, Ukraine has been striking Russian territory with Western weaponry for more than a year, since when it first started using it against targets in Crimea. When Russia formally annexed more Ukrainian territories, those strikes expanded accordingly. So, as far as Russia is concerned, there would be no major escalation if Western donors permitted Ukraine to use their weapons with fewer geographic restrictions.

Besides, the Russians have been crying wolf for far too long for such theatrics to look credible. They've been insisting that the West was at war with them since even before the invasion. They've been issuing dire threats against the West since before the invasion. And they've been repeating basically the same things at regular intervals all throughout the campaign. Unfortunately, the West all too often plays an obliging dupe to such crude intimidation tactics. -

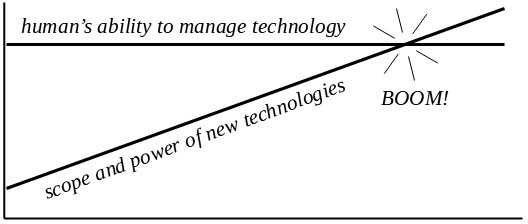

I am building an AI with super-human intelligence

One day, we’ll invent some superpower, try it out and our planet explodes.

I call it the theory of BOOM.

:rofl: -

Site Rules Amendment Regarding ChatGPT and SourcingQuick question, do you find that different languages shape the way you feel? — frank

Not that I've noticed. Perhaps a psychology experiment could tease that out. -

Site Rules Amendment Regarding ChatGPT and SourcingAs a child and teen, lacking any talent for foreign languages, I was completely unable to learn English in spite of its being taught to me every single year from first grade in primary school until fifth grade in secondary school. Until I was 21, I couldn't speak English at all and barely understood what was spoken in English language movies. I thereafter learned alone through forcing myself to read English books I was interested in that were not yet translated into French, and looking up every third word in an English-to-French dictionary. Ever since, I've always struggled to construct English sentences and make proper use of punctuation, prepositions and marks of the genitive. — Pierre-Normand

I was never good at memorization, so formal language learning wasn't easy. And there wasn't much conversational practice available. Like you, at some point I just purposefully started reading - at home, in transit, powering through with a pocket dictionary. Reread English children's classics with great pleasure, now in the original - Winnie the Pooh, Alice in Wonderland, etc. - then tackled adult fiction. Reading built up vocabulary and gave me a sense of the form and flow of the language. I still don't know much formal grammar - I just know (most of the time) what looks right and what doesn't. I suppose that this is not unlike the way LLMs learn language.

Oftentimes, I simply ask GPT-4 to rewrite what I wrote in better English, fixing the errors and streamlining the prose. I have enough experience reading good English prose to immediately recognise that the output constitutes a massive improvement over what I wrote without, in most cases, altering the sense or my communicative intentions in any meaningful way. The model occasionally substitutes a better word of phrase for expressing what I meant to express. It is those last two facts that most impress me. — Pierre-Normand

Yeah, thanks, I'll experiment with AIs some more when I have time. I would sometimes google the exact wording of a phrase to check whether it's correct and idiomatic. An AI might streamline this process and give better suggestions. -

Site Rules Amendment Regarding ChatGPT and SourcingI mean even banning it for simple purposes such as improving grammar and writing clarity. Of course this will rely on the honesty of posters since it would seem to be impossible to prove that ChatGPT has been used. — Janus

One learns to write better primarily through example and practice, but having a live feedback that points out outright mistakes and suggests improvements is also valuable.

As a non-native speaker, much of my learning is due to reading and writing, but that is because I am pretty long in the tooth. Once spell- and grammar-checkers came to be integrated into everything, I believe they did provide a corrective for some frequent issues in my writing. I've briefly experimented with some free AI tools for improving style, but so far I haven't been very impressed by them. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansSadly, I don't know enough to understand your attempt. I'm reading all kinds of things. Haphazardly, since I'm just singing it. So probably unproductively. But maybe I'll get there. SEP seems helpful.

However, the difference between neural activity/consciousness and moving feet/walking is vast. I can't even see any common ground. — Patterner

I intentionally picked a frivolous and perhaps imperfect parallel to sharpen the issue. Perhaps it would go easier with an example from physical sciences, such as the relationship between fluid dynamics and molecular dynamics. But let's just leave it.

The brain's activity could do these things without any subjective experience/consciousness anywhere. And I'm sure we're making robots that prove the point. But let's say we add another system into the robot. Let's call it a kneural knet. The kneural knet observes everything the robot is doing, and generates a subjective experience of it all. We built and programmed the kneural knet, and we know it absolutely does not have any ability to affect the robot's actions.

Isn't this what epiphenomenalism is saying? — Patterner

This is more towards philosophical zombies. -

Empiricism, potentiality, and the infiniteWell, I wrote and lost a long reply to this — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's a shame...

There is a cluster of concepts closely related to potential: possibility in all its forms, probability, powers, dispositions. All of them have reasonable applications in thought. But where is the actual tension with empiricism? It would take an unreasonably austerer form of empiricism to deny all of that.

In regard to observations, I know of no empiricists who would deny being to all but observed instances (sense-impressions)? That's as good as (or as bad as) solipsism. Empiricism goes hand-in-hand with inference, and why not infer towards potential, etc.? There can be particular objections, but I don't see a path from empiricism to denying potential and the like tout court. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansAlso, walking is moving our feet. For simplicity, it's the word we use instead of spelling out the whole process. I don't say;

While upright, which is possible thanks to visual cues and the delicate workings of my inner ear, I moved my feet, alternating them, always placing the rear one in front of the other, until I found myself at the store.

instead, I just said I walked to the store. — Patterner

Well, that's what identity theorists say about consciousness vs neural activity. There are arguments against identity theory (other than epiphenomenalism), and similar arguments could also be deployed against the identity of walking and putting one foot in front of the other. But whether it's identity physicalism, reductive physicalism, emergence or anything else besides eliminativism, epiphenomenalism is supposed to argue against that on the grounds that consciousness appears to be superfluous if neural activity does all the causal work. My reductio aims to demonstrate that this argument is based on a misunderstanding of causality. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansAccording to the definitions I quoted earlier, epiphenomenalism says mental states do not have any effect on physical events. Walking is a physical event, not a mental event. And walking certainly has an effect on physical events. So I don't know how you are thinking walking is epiphenomenal. — Patterner

I already addressed this. The causal exclusion argument that motivates epiphenomenalism applies equally to physical events in a similar supervenient relationship. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansTrying and trying to figure out what you mean, but I'm not getting it. But I feel this sentence is key. Can you explain the relationship between moving your feet and walking? (Of course, we're not talking about sitting in a chair and shuffling your feet around. Or lying on the ground doing leg-lifts. Or pumping your legs on a swing to gain height. Or any number of things other than moving them in the way that produces walking.) — Patterner

Right, just as when you say "neutral activity is wanting to have milk" you don't mean just any random neural activity, but specifically whatever activity is responsible for/constitutes the experience of wanting to have milk.

Similarly, moving your feet in a certain way is responsible for/constitutes walking. I am not sure why you are having a difficulty with this parallel. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansIn what way does the physical act of walking fit any definition of epiphenomenal? I may be misunderstanding your questions. — Patterner

Originally, epiphenomenalism was indeed articulated in relation to mental/physical relationship. However, the justification for it does not rely on any uniquely mental aspects and can be applied more widely. You have gestured towards this justification earlier in the discussion:

I guess there are those who say the neural activity isn't experienced as wanting to have milk. Rather, the neutral activity is wanting to have milk. Experiencing the neural activity vs. the neural activity being the experience. The latter being the case if we are ruled by physical determinism. In which case, the "wanting to have milk" is, I guess, epiphenomenal, and serves no purpose. — Patterner

The idea, known as causal exclusion, is that if A (neural activity) does all the work, then B (experience) has no causal efficacy. Surely, you can see that this is in no way specific to mental phenomena? So, if moving your feet does all the causal work, then walking is reduced to an epiphenomenon. -

Rational thinking: animals and humansI would not think so. — Patterner

Why not? Moving your feet does all the work, so why would we need walking?

SophistiCat

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum