Comments

-

The Notion of Subject/ObjectYes, I see what you mean. Newtonian absolute space/time was the view prior to relativistic spacetime. — Mww

Yes.

That is, through experience, Einstein's Relativity has replaced Newtonian Physics. Doesn't that contradict the Kantian view?

— Andrew M

I’m not understanding what in Einstein would contradict Kant. Where did Einstein prove Kant wrong, in as much as they each operated from two distinct technological and scientific domains? Kant had no significant velocities other than a horse, and there were no trains, which together negate even the very notion of time differential reference frames, so there wouldn’t appear to be any reason for Kant to notice measurable discrepancies in rest/motion velocities. — Mww

He had no reason to notice, perhaps. But the discrepancies are there and we've subsequently discovered, per Relativity, that the geometry of space and time is non-Euclidean. Which means that Kant's (synthetic a priori) judgments about space and time have been falsified by experience.

What problem is there, that the natural distinction above solves? — Mww

The stick example shows that one can be mistaken about what they think they've perceived. So the language term "appear" is introduced to represent that situation (e.g., the straight stick appeared to be bent). The problem it solves is to give us language for describing a naturally-occurring situation. Things aren't always as they appear to be.

Appearance in Kantian terminology can’t be artificial in any sense, because it is a representation of sensation. If there is a sensation, there will be an appearance, period. And it is necessarily a one-to-one correspondence between sensation and appearance, otherwise there is no ground for the subsequent cognitive procedures, which falsifies the entire system. Appearance in Kant is like making the scene, as in “...that which appears...”, not what a thing looks like, because the advent of appearance in the system is long before cognition, which means there is nothing known whatsoever about the appearance except that one has occurred, been presented, to the system. Thus, it shouldn’t be said that that which is unknown at a certain time is thereby artificial. — Mww

You're showing the role the term plays in Kant's system. Fair enough. But that shifts the question to be about his system as a whole. What problem is it solving?

Did Kant think that our existing language that we use to represent the world and acquire knowledge somehow fails us? -

The Notion of Subject/Object'First philosophy' or metaphysics is concerned with the ultimate nature of reality. In a theistic metaphysics, then God is understood as being the source or ground of being. A naturalistic philosophy doesn't countenance such an idea as God is (by definition) super-natural, 'above' or transcendent to nature. So the attitude generally is, whatever hypothesis you want to consider, it can't include something which is by definition above and beyond the naturalist framework- which is what I'm calling 'metaphysical naturalism'. You see in many atheist arguments (including many posted here) that science proves or at least suggests that the world has a naturalistic explanation or can be thoroughly understood in naturalistic terms and that there is nothing outside or above or transcendent to nature in terms of which understanding ought to be sought. — Wayfarer

That particular definition notwithstanding (which is a modern one, btw), I don't think naturalism presupposes an answer about God one way or the other. Aristotle was a natural philosopher and, on the basis of his observations of the world, argued for an Unmoved Mover.

Now whether or not his argument is correct, its seems to me that he didn't consider his argument to be going beyond nature or transcending nature. Instead he was just continuing to apply the same natural methodology to ultimate things. For Aristotle, knowledge of the universal always proceeds from the particular.

As you know, the Scholastics (as with Aristotle) considered themselves to be making natural arguments for the existence of God, which was termed natural theology as opposed to revealed theology.

Now fast-forward to Descartes:

René Descartes' metaphysical system of mind–body dualism describes two kinds of substance: matter and mind. According to this system, everything that is "matter" is deterministic and natural—and so belongs to natural philosophy—and everything that is "mind" is volitional and non-natural, and falls outside the domain of philosophy of nature. — Natural philosophy - scope

Here we see Descartes placing limits on what can, in principle, be known in the context of natural philosophy.

This is where Kant is relevant - recall that he said that a central goal of his critical philosophy is to 'discover the limit to knowledge so as to make room for faith'.

I'm arguing that is that it is possible to pursue a naturalist account while still understanding that it has limits in principle - that the naturalist account is not all there is (which is what I understand Kant to be saying.) That is what I mean by distinguishing methodological from metaphysical naturalism - the former sets aside or brackets out metaphysics in pursuit of the naturalist account. But it doesn't necessarily say anything about what if anything might be beyond that. It's close in meaning to Huxley's agnosticism. — Wayfarer

So I would note that the premise of in-principle limits on knowledge is contrary to the premise that ultimate themes can be investigated in the context of natural philosophy.

In my view, naturalism doesn't presuppose either theism or atheism any more than it presupposes either Newtonian physics or Einsteinein relativity. Instead, whatever one's hypothesis, an argument from nature should be made. The relevant distinction isn't between naturalism and theism, but between naturalism and dualism. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectIf we see a straight stick partly submerged in water, we notice that it appears bent. This gives rise to the natural distinction between what something is (e.g., a straight stick) and how it appears under different conditions (e.g., the stick appears bent when partly submerged in water and it's possible to mistakenly think that the stick is bent).

— Andrew M

Even Bishop Berkeley had an answer for that! — Wayfarer

Given the above distinction, what conceptual problem remains?

It really isn't so simple. Again, in physics, the question has been suggested by the conundrums sorrounding 'wave-particle' duality, for example.

I think the key point is that if you accept naturalism simply as a methodological assumption, then there's no problem to solve (which is I think what you are suggesting.) — Wayfarer

There are still plenty of problems to solve even with that assumption (including philosophical) but at least they are then, in principle, solvable.

I think Kant's argument comes into play when metaphysical conclusions are drawn on the basis of methodological axioms - in other words, when arguments are made about first philosophy on the basis of scientific naturalism. — Wayfarer

On naturalism, the methodological assumption of naturalism is reflected back on itself (i.e., as the study of the study of nature). So why would that be a problem and how would Kant's argument be relevant here? -

The Notion of Subject/Objectthe (contingently) prior background

— Andrew M

...is categorically opposed to the Kantian a priori meaning, for any contingently prior background is merely another way to say “experience”.

“....By the term "knowledge a priori," therefore, we shall in the sequel understand, not such as is independent of this or that kind of experience, but such as is absolutely so of all experience. Opposed to this is empirical knowledge, or that which is possible only a posteriori, that is, through experience...”

Thus,.......consider the geocentrists whose a priori view was that Earth was the center of the universe, might better be said.....whose prior view. — Mww

Cool. So my suggestion is that this should similarly apply to absolute space/time and relativistic spacetime.

That is, through experience, Einstein's Relativity has replaced Newtonian Physics (which approximates the predictions of Relativity in special cases).

An implication of the Kantian view is that two events that are simultaneous for one observer are simultaneous for all observers.

— Andrew M

Two events for a guy and guy standing right beside him, will be simultaneous to both, yes. The difference between the observations will be immeasurable. — Mww

OK, but for a third guy walking past, those two events won't be simultaneous.

Doesn't that contradict the Kantian view?

On sticks in water....

“.....It is not at present our business to treat of empirical illusory appearance (for example, optical illusion), which occurs in the empirical application of otherwise correct rules of the understanding, and in which the judgement is misled by the influence of imagination...” — Mww

Yes. So it seems to me that Kant's notion of appearance is artificial. What problem does it solve that we haven't already solved with the natural distinction above. -

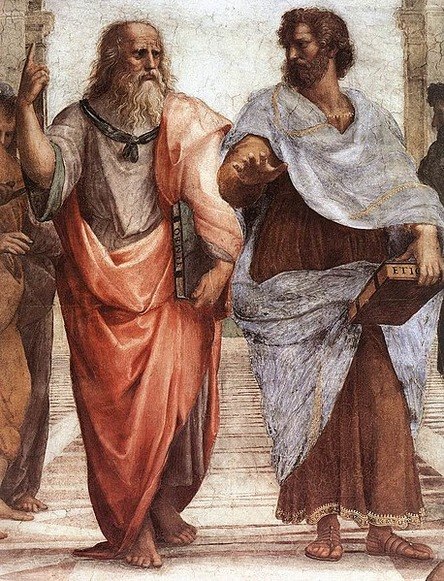

The Notion of Subject/ObjectOn naturalism, there is no "reality of appearances". We're not trapped in Plato's cave.

— Andrew M

with the caveat that:

Naturalism doesn't confer certainty.

— Andrew M

The natural claim is that we can know things as they are (from our perspective as human beings).

— Andrew M

If we have to qualify it in this way, then does it really constitute 'knowing things as they are'? By conceding the perspectival nature of knowledge, you're more or less conceding Kant's point. — Wayfarer

No, because there's a key difference in how Kant construes the perspectival nature of knowledge and that is in his understanding of appearance.

Here's an illustrative example. If we see a straight stick partly submerged in water, we notice that it appears bent. This gives rise to the natural distinction between what something is (e.g., a straight stick) and how it appears under different conditions (e.g., the stick appears bent when partly submerged in water and it's possible to mistakenly think that the stick is bent).

On Kant's view, both scenarios constitute mere appearances (which we can know). But we can't know the thing-in-itself. Thus he has collapsed the natural distinction and created a new and artificial distinction. As Kant put it:

And we indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something. — Prolegomena, § 32

I'm wary of the use of the word 'creation' in this context. But thinking about it some more, it's close in meaning to what Andrei Linde says in the Closer to Truth interview that I linked to. Of course it seems obviously absurd when we think of it in terms of 'the world being in the mind' - but the problem is that when we're saying this, we're trying to envisage 'the world' and 'the mind' from the outside. There's the vast universe, the whole Earth is just a minute speck in relation to that. But we can't see it 'from the outside', we can't make an object of 'me knowing that'. It's a false perspective. — Wayfarer

There is only a problem if an object is defined in terms of outside/inside (thing-in-itself/appearance). If an object is instead defined in terms of what we observe (i.e., what we can ostensively point at) then we can know it as it is. Such as the stick from the above example.

That is why I reject the idea of a "view from nowhere" which tacitly assumes a thing-in-itself/appearance dualism. Instead, knowledge claims are made by human beings and so presuppose a human perspective. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectConsider the geocentrists whose a priori view was that Earth was the center of the universe and that the Sun moved across the sky. The heliocentrists replaced that with their own a priori view that it was the Earth that moved around the Sun.

— Andrew M

What is it about those views that make them a priori? — Mww

They comprise the (contingently) prior background against which observations are interpreted and judgments are made. That prior background can be represented in scientific or mathematical terms.

To change one's view from geocentrism to heliocentrism is to change that background - a Kuhnian paradigm shift, or gestalt shift.

Even in Einstein, the observer in his own reference frame is in the Kantian view of Euclidean space and time. — Mww

I'm not sure what you mean. An implication of the Kantian view is that two events that are simultaneous for one observer are simultaneous for all observers. But that's not the case under Einstein's relativity (see relativity of simultaneity). -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectPut differently, mind is an abstraction over a concrete particular, in this case a human being.

— Andrew M

An electromagnetic dynamo is an abstraction. It's still a powerful thing. We smart humans can navigate these kinds of situations without straying into category errors. — frank

What I mean by abstraction in this context is "A particular way in which a thing exists or appears." (Lexico, form) [*]

An electromagnetic dynamo is a thing that exists, not a particular way in which a thing exists (i.e., it's concrete, not abstract or formal).

--

[*] Per the surrounding discussion on Kant, it's interesting to note the Latin origin of form and its similarity to 'template' and 'mold':

"Middle English from Old French forme (noun), fo(u)rmer (verb, from Latin formare ‘to form’), both based on Latin forma ‘a mould or form’." -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectUse of the word "mind" is a convenient façon de parler (Bennett & Hacker, 2003). — Galuchat

Thanks for that apt reference. It's well worth quoting the original passage in full.

Talk of the mind, one might say, is merely a convenient facon de parler, a way of speaking about certain human faculties and their exercise. Of course that does not mean that people do not have minds of their own, which would be true only if they were pathologically indecisive. Nor does it mean that people are mindless, which would be true only if they were stupid or thoughtless. For a creature to have a mind is for it to have a distinctive range of capacities of intellect and will, in particular the conceptual powers of a language-user that make self-awareness and self-reflection possible. — Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience - Bennett and Hacker -

Curry's ParadoxBut the Curry statement does terminate. It is self-referential but doesn't result in an infinite loop. — TheMadFool

It doesn't terminate. Here's the expansion:

1. If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China

expands to

2. If 'If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China' is true, then Germany borders China

expands to

3. If "If 'If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China' is true, then Germany borders China" is true, then Germany borders China

expands to

4. ...

and so on indefinitely. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectKant's idea, which I assume, is that the a priori is something like a template that we apply to the world.

— David Mo

Common interpretation, that. A template impressed on the world to which it must conform. I would rather think a priori reason is the mold into which the world is poured. The only difference, which is more semantic than necessary perhaps, is that template implies projection of the mind onto the world, and mold implies receptivity of the world into the mind. Just depends on one’s choice in understanding of the relationship between mind and world. — Mww

I like the template and mold ways of thinking of it. However I'd like to suggest that the a priori - the template or mold - is itself fluid.

Consider the geocentrists whose a priori view was that Earth was the center of the universe and that the Sun moved across the sky. The heliocentrists replaced that with their own a priori view that it was the Earth that moved around the Sun. Same phenomenology, different template.

Apply that idea to space and time. Kant's a priori view was Euclidean. But Einstein replaced that with spacetime relativity. Same phenomenology, different template. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectWhich is to say, the Earth's orbiting of the Sun in the early universe doesn't presuppose an experiencer and an object of experience.

— Andrew M

I dont think Descartes suggested that it does, did he? — frank

Probably not. But Descartes set the stage for thinkers that came after him. See, for example, the passage from Magee's book on Schopenhauer that includes, "the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding". That is, the empirical world depends on its dual subject.

(Though note Wayfarer suggests that that passage might be misleading.)

I dont really see what work substance dualism does beyond saying that mind is irreducible.

Irreducibility is compatible with science. It's been argued that it's more compatible than the alternative. — frank

Ryle's argument is that mind refers to (or reduces to) a human being's intelligent activity. That Bob has a keen mind means that he's a smart guy; that he's lost his mind means that he's done something stupid, or that he's insane. It's not a substantial thing like a body. That's the Cartesian error.

Put differently, mind is an abstraction over a concrete particular, in this case a human being.

That way of thinking about the world goes back to Aristotle (e.g., the soul is the form of the body). Aristotle's form/matter distinction was abstract, unlike Descartes' substance dualism. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectAs the passage I quoted acknowledged, the reality of the early universe is no more being rejected than that of the 'pen with which these words are written'; but that it remains the reality of appearances. — Wayfarer

On naturalism, there is no "reality of appearances". We're not trapped in Plato's cave.

Empirically speaking, I agree with you. But philosophically, it remains possible that we're all denizens of the Matrix, or projections of a grand simulation. So the purported 'facts of natural science' do not constitute the slam-dunk argument that you seem to believe they do. They're certain, given that .... . — Wayfarer

Yes, they remain possible. Naturalism doesn't confer certainty.

Kant never said that 'the world is completely unknowable'. Kant said that we know the world as appearance; it's not simply non-existent or unreal or a phantasm. I don't know if he would have used the expression that the world is a 'product of the mind' (and in this respect, that passage from Magee that I quoted might be misleading); it's that we know the world as it appears to beings with minds of the kind we have. On that basis, we project what we understand as 'the real world'. This is the activity of the most complex organ known to science, namely, the human brain. — Wayfarer

So at issue is the dualism between "the unknown thing in itself" and "knowledge of appearances".

The natural claim is that we can know things as they are (from our perspective as human beings).

That captures what you're saying above without the dualism. -

Curry's ParadoxKindly explain the difference between terminating and non-terminating self-reference in re to Curry's paradox. — TheMadFool

What I mean by terminating self-reference is that there exists a method for evaluating the sentence in a finite number of steps. Consider the following sentence:

This sentence has five words

That sentence is self-referential and the self-reference terminates because a procedure can be defined that counts the number of words in the sentence. So the sentence is well-defined and has a truth value (true in this case).

The Curry sentence is this P1 := P1 > P2. How is it not well-defined. There are no syntactical or semantic errors as far as I can see. — TheMadFool

First, for a more familiar example, consider the Liar sentence:

This sentence is false

That sentence has a non-terminating self-reference. To evaluate the full sentence, it is first necessary to evaluate the referent of "This sentence", which is "This sentence is false". So the sentence expands to:

"This sentence is false" is false

But now to evaluate the inner sentence, it is first necessary to evaluate the referent of "This sentence". And so the expansion of the sentence continues and doesn't complete in a finite number of steps. That is, the sentence is not well-defined and fails to be truth-apt.

Now if a formal system allows this kind of sentence and assumes it is truth-apt, then the result is trivialism which is generally not what is wanted. So the formal system must be fixed in some way to avoid that result (such as by excluding that type of sentence, or by limiting explosion as with paraconsistent logics).

The same situation occurs with the Curry sentence:

If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China

Similar to the Liar sentence, this expands to:

If "If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China" is true, then Germany borders China

Continuing in this vein, the expansion also fails to complete in a finite number of steps. That is, the sentence is similarly not well-defined and fails to be truth-apt. As with the Liar sentence, the formal system must be fixed in some way to avoid trivialism. That's easier said than done. Nonetheless, the non-terminating self-reference is the crux of the problem. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectThe issue with subject/object dualism is that it affects (or infects, depending on one's perspective) the way people look at everything such that it is difficult to conceive of any alternative.

— Andrew M

Yes, I suppose. We talk usually in the form, “We think....”, “You know...”, “I am....”, and so on, which makes explicit a subject/object dualism in general intersubjective communications. But I wouldn’t call that an issue as much as I’d call it linguistic convention. Nature of the beast, so to speak, and definitely makes it difficult to conceive an alternative. — Mww

Yes, I agree those are linguistic conventions. But they don't assume dualism. On the ordinary use, it is the human being that thinks (and is the referent of "I"), not their mind.

Whereas it is phrases like "the external world" or "out there" that assume subject/object dualism. They are philosophical usages, not ordinary conventions. Which is fine, that's what we're discussing, but I think it's important to be mindful of that. (That was a conventional use of "mindful", by the way...) -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectAs I see it, Descartes was confused by mind idioms that lead to him positing his mind/body distinction.

— Andrew M

I don't agree. In stripping away everything we can doubt, he was denying the Church a place at the foundations of our thinking, and understood in the way I think he intended, his conclusion is correct. — frank

Actually I was referring to Descartes' substance dualism there, not cogito ergo sum. As Gilbert Ryle has argued, Cartesian dualism is a category mistake.

If you subsequently realize that the experiencer and the object of experience (subject and object) are inextricably bound together logically, IOW, subject and object fall out of an analysis of experience or they're the product of reflection on experience, that doesn't undermine the value of the concepts. — frank

That's fine when talking about human experience. The trouble arises when universalizing the distinction beyond human experience.

Which is to say, the Earth's orbiting of the Sun in the early universe doesn't presuppose an experiencer and an object of experience. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectModern science wants to imagines a world without 'the subject' in it, as if from no viewpoint at all. — Wayfarer

Not so. The viewpoint of modern science today is that the Earth orbited the Sun a billion years ago. But there was no viewpoint a billion years ago.

The point is, the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding, which apprehends all the objects of empirical knowledge within it as being in some part of that space and at some part of that time: and this is as true of the earth before there was life as it is of the pen I am now holding a few inches in front of my face and seeing slightly out of focus as it moves across the paper.

Which is just to say that we view the world in a particular way (in our capacity as human beings). Not that we literally create the world that existed prior to our existence.

[i.e. we have to learn to look at our naturalistic spectacles rather than just through them, which takes a kind of cognitive shift.]

Yes it does. But the point at issue is what we see through our natural spectacles. The natural world (from a human viewpoint), or a Platonic shadow world?

Now this explains how Kant can be both an empirical realist AND at the same time, a transcendental idealist. Many people - I suspect you also! - will think that Kant (and I) are saying that 'the world exists only in the mind of the observer'. He's not saying that - but he's also questioning the (generally implicit) view that most of us have, that the world exists completely independently of our perception of it (as per scientific realism). However, he's pointing out that there is an implicitly subjective element in every statement, every perception, even objective statements (which are to all intents, true to all observers, but only because of the kinds of observers that we are). — Wayfarer

Here's my stab at it. Per Kant, there's a real world but it's completely unknowable. What we can investigate is the empirical world that is the product of various stages of conditioning by the mind. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectTo give a stock example, the Earth orbited the Sun long before humans came on the scene to construct a theory of heliocentrism. It seems that we can talk about that in ordinary language (introducing scientific or mathematical language where relevant). What does Kant's system, or subject/object dualism generally, contribute here?

— Andrew M

transcendental realism...regards space and time as something given in themselves (independent of our sensiblity). The transcendental realist therefore represents outer appearances (if their reality is conceded) as things in themselves, which would exist independently of us and our sensibility and thus would also be outside us according to pure concepts of the understanding.

CPR, A369 — Wayfarer

Thanks for replying. I'm reading your comments below as an application of Kant's system.

What you're not seeing is the way the mind - not just your mind, or my mind - constructs the entire stage within which perspective and judgements of the age of the Universe exist.

"The problem of including the observer in our description of physical reality arises most insistently when it comes to the subject of quantum cosmology - the application of quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole - because, by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers. Andrei Linde has given a deep reason for why observers enter into quantum cosmology in a fundamental way. It has to do with the nature of time. The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time loses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe. So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'."

(Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271) — Wayfarer

As we've discussed before, observer in its physics sense does not imply mind or consciousness, it instead refers to a measurement apparatus or reference frame. As Heisenberg put it, "Of course the introduction of the observer must not be misunderstood to imply that some kind of subjective features are to be brought into the description of nature."

So what the above passage says is that, taken as a whole, the universe is predicted to be static and unchanging (per the Wheeler-DeWitt equation). In order to predict a dynamic and changing universe, one must split it into subsystems where time and change emerge as a relational or relative measure between those subsystems. That's the case even if the subsystems are simply a lifeless planet + the rest of the universe.

Alternatively, let's see what your reading commits you to here. Before sentient life emerged on Earth there were no conscious observers. Therefore the universe must have been static prior to sentient emergence. Therefore it only appears as if the Earth were orbiting the Sun at an earlier time. But that consequence is one reason why virtually no-one holds the "consciousness causes collapse" interpretation in quantum mechanics. As John Bell put it:

It would seem that the theory is exclusively concerned with ‘results of measurements’ and has nothing to say about anything else. When the ‘system’ in question is the whole world where is the ‘measurer’ to be found? Inside, rather than outside, presumably. What exactly qualifies some subsystems to play this role? Was the world wave function waiting to jump for thousands of millions of years until a single-celled living creature appeared? Or did it have to wait a little longer for some more highly qualified measurer — with a Ph.D.? If the theory is to apply to anything but idealized laboratory operations, are we not obliged to admit that more or less ‘measurement-like’ processes are going on more or less all the time more or less everywhere? Is there ever then a moment when there is no jumping and the Schrödinger equation applies? — John S. Bell - Quantum mechanics for cosmologists -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectLinguistic convention says there are basketballs out there; transcendental idealism says there are objects out there only called basketballs because the human represents the object to himself as such. — Mww

Just to inject a few words about linguistic convention... ;-)

Linguistic convention allows us to talk about basketballs and humans (grammatically interchangeable as subjects or objects depending on what one wants to say). But linguistic convention doesn't say that basketballs are "out there" - that kind of "in here/out there" distinction is itself made using language and depends on one's philosophical commitments.

As I see it, Descartes was confused by mind idioms that lead to him positing his mind/body distinction. Locke, Hume and Kant then subsequently carried that line of thinking to its logical conclusions. The issue with subject/object dualism is that it affects (or infects, depending on one's perspective) the way people look at everything such that it is difficult to conceive of any alternative.

That's not an argument for or against it (here at least). But just to point out how it can subtly frame the way we look at the world. -

Curry's ParadoxWell, the paradox rests on self-reference and I don't have a clue why computers can't handle self-reference. However, humans fare better at it, hence the paradox. — TheMadFool

Computers can handle self-reference as long as the self-reference eventually terminates.

The Curry sentence is not well-defined due to the non-terminating self-reference. Treating it as if it were well-defined (and thus evaluable as either true or false) is what leads to paradox. -

Curry's Paradoxif (germanyBordersChina() is true)

— Andrew M

There shouldn't be "if" in the above statement. — TheMadFool

That is there simply to make the return values explicit (per the truth table for p --> q) and doesn't affect the logic. But if you prefer, the algorithm can be simplified to the following:

bool result = theCurrySentence() is true bool theCurrySentence() { if (theCurrySentence() is true) then return (germanyBordersChina() is true) else return true }

The problem is that theCurrySentence() function can't be evaluated until the antecedent is evaluated. But the antecedent can't be evaluated until theCurrySentence() function that it calls is evaluated. So nothing gets evaluated and no truth value is returned. The algorithm just endlessly loops. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectYes. But in quantum mechanics (not philosophy) the subjective means the problem of measurement, that is to say, the fact that some objects cannot be known -or even exist- independently of the fact to be measured. May be "intersubjective" would be more accurate, but usually they are called "subjective". In any case not "objective". — David Mo

An interpretation-neutral term that captures that is counterfactual definiteness (i.e., the ability to speak "meaningfully" of the definiteness of the results of measurements that have not been performed). Almost all quantum interpretations reject counterfactual definiteness (the notable exception being the de Broglie-Bohm interpretation).

See also below, which echoes Heisenberg's concern that I quoted earlier:

Because it asserts that a wave function becomes 'real' only when the system is observed, the term 'subjective' is sometimes proposed for the Copenhagen interpretation. This term is rejected by many Copenhagenists[24] because the process of observation is mechanical and does not depend on the individuality of the observer. — Copenhagen interpretation - Metaphysics of the wave function

What it seems important as principle in Kant is the regulative use of the reason. That is to say: physics principles are a priori because they come from a priori conditions of our knowledge, not being things in themselves. This links with Kuhnian concept of paradigm and with quantum paradoxes of measurement, relativity, etc. We live a world mediated by the categories of our way of thinking. — David Mo

So the issue is that there doesn't seem to be a use in physics (or philosophy of physics) for notions like "things in themselves" and "a priori conditions of knowledge".

To give a stock example, the Earth orbited the Sun long before humans came on the scene to construct a theory of heliocentrism. It seems that we can talk about that in ordinary language (introducing scientific or mathematical language where relevant). What does Kant's system, or subject/object dualism generally, contribute here? -

Curry's ParadoxHow would you evaluate a conditional sentence in a way different to the way I did the Curry's sentence? — TheMadFool

By constructing an algorithm for evaluating it. Here's a Curry sentence from Wikipedia:

If this sentence is true, then Germany borders China.

The sentence can be represented algorithmically as follows:

bool result = theCurrySentence() is true bool theCurrySentence() { if (theCurrySentence() is true) then { if (germanyBordersChina() is true) then return true else return false } else return true }

When running this algorithm, the function theCurrySentence() will never return a truth value. So the sentence it represents is not truth-apt.

Truth tables can be used to explore all possibilities. — TheMadFool

That assumes that the sentence is truth-apt in the first place. Which is always a potential issue when formalizing natural language sentences. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectAnd subjectivity does not only mean consciousness, but also relativity with respect to measurement, something that nobody or almost nobody denies in quantum mechanics: the collapse of the wave function. — David Mo

OK, but per consciousness, almost everybody in quantum mechanics denies that consciousness causes collapse.

Here are the definitions of subject and object that seem to best fit the OP's meaning:

A subject is a being who has a unique consciousness and/or unique personal experiences, or an entity that has a relationship with another entity that exists outside itself (called an "object").

A subject is an observer and an object is a thing observed. This concept is especially important in Continental philosophy, where 'the subject' is a central term in debates over the nature of the self.[1] The nature of the subject is also central in debates over the nature of subjective experience within the Anglo-American tradition of analytical philosophy.

The sharp distinction between subject and object corresponds to the distinction, in the philosophy of René Descartes, between thought and extension. Descartes believed that thought (subjectivity) was the essence of the mind, and that extension (the occupation of space) was the essence of matter.[2] — Subject (philosophy)

I've been arguing in this thread that relativity with respect to measurement is the natural framework here (I earlier mentioned Einstein's special theory of relativity). But that rejects subject/object dualism per the above definitions. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectThis is the closest anyone has come to providing an answer:

It is quite clear Kant thought science to be the direction metaphysics should follow, which is pure reason applied to something, not that pure reason should be the direction science should follow.

— Mww

I've not read anything in this thread since that comment which convinces me that Kant has anything to do with Science generally. — Galuchat

In terms of Kant's philosophy, that's my conclusion as well (his specifically scientific contributions notwithstanding as Mww mentions). -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectI have not understand what symmetry you refer. — David Mo

Per symmetry, a measurement is simply an interaction between two quantum systems (with no implication of consciousness or subjectivity in either system).

Anyway, Bohr, Einstein, Heisenberg et alia thought that quantum mechanics posed a problem of subjectivity to science. — David Mo

They didn't. Heisenberg, for example, said:

Of course the introduction of the observer must not be misunderstood to imply that some kind of subjective features are to be brought into the description of nature. The observer has, rather, only the function of registering decisions, i.e., processes in space and time, and it does not matter whether the observer is an apparatus or a human being; but the registration, i.e., the transition from the "possible" to the "actual," is absolutely necessary here and cannot be omitted from the interpretation of quantum theory. — Werner Heisenberg - Physics and Philosophy

--

Bernard d'Espagnat (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_d%27Espagnat) devoted an article to the importance of Kant to understand quantum mechanics. — David Mo

I'm not familiar with his writings. Can you, or anyone else, explain why Kant should be considered important for understanding QM or science generally? -

Curry's ParadoxYou're just plugging in values to see what happens. That's not the same as evaluating the sentence. It has the same issue as the Liar and Truth Teller sentences.

Another way of stating it is that each of those sentences are ungrounded. There is nothing that determines their truth or falsity (i.e., they don't meaningfully assert anything). -

Curry's ParadoxThe main statement is: If this sentence is true, then P2 — TheMadFool

The problem with the Curry sentence is that it's not evaluable and thus not truth-apt. The truth value of the antecedent depends on the truth value of the sentence. But the truth value of the sentence depends on the truth value of the antecedent (and consequent). So the sentence has a circular dependency. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectThe most spectacular reference is quantum mechanics, where the act of measuring creates the measured. — David Mo

That's an interesting statement in the context of this thread. The relevant question is whether it points to a subject/object duality or to an underlying symmetry. That is the measurement problem.

But even in relativity, there is still an objective truth. Space and time may distort relative to an observer, but a spacetime interval is the same for all observers. Simultaneity may be relative to an observer, but cause and effect are still the same for all observers. And the impetus behind all of that, the speed of light is the same for all observers: all the things that are relative are reasoned to be so because they must be in order to account for the speed of light being an objective, non-relative value. — Pfhorrest

Yes. So I'd just like to note the symmetry here with respect to observers. The train has a velocity relative to the platform or, symmetrically, the platform has a velocity relative to the train. No subject/object duality is implied. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectThe view from nowhere exists because science has to abstract from human perceptual relativity to get at the way things are, and not just as they appear to us. Otherwise, we're left with ancient skepticism or some form of idealism. — Marchesk

I think Special Relativity provides a useful model here. Things can have different properties in different reference frames (and one can translate between reference frames). But there is no absolute reference frame for how things "really" are.

Similarly, things can have properties that depend on one's perceptual machinery (which again we can discover). But there is no perception-free perspective.

That's nice and all, but one still has to deal with intentionality, consciousness and epistemology. — Marchesk

Yes, but it's sensible to stop using demonstrably broken frameworks. Imagine trying to model the Big Bang using the Ptolemaic model. Perhaps it can be done, but why unnecessarily handicap oneself? -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectCan you be more specific? How does falsifiability and paradigm shift, for example, imply a subject/object dualism?

— Andrew M

Both deal with scientific theories, and a knowing subject is thus assumed.

And again, I’m not necessarily talking about mind/body dualism. I’m talking more about Kant’s variation- that we as subjects have representations of the outside world (the phenomenon, the object). — Xtrix

There is the obvious sense in which a human being is needed to propose a scientific theory. Also any theory will be in human language, both ordinary and technical.

So I think naturalists and dualists can agree on that.

But what a scientific theory is about doesn't require a "knowing subject". For example, the Earth orbited the Sun long before life emerged to construct a theory of heliocentrism. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectScience is still a human enterprise, and looks at the cosmos through the human perspective, even if it is highly abstracted and methodologically rigourous. — Wayfarer

That science is a human enterprise conducted from a human perspective is entirely consistent with naturalism. The "view from nowhere" is just how a dualist sees naturalism. The dualist thinks that if the ghost is dispensed with, then so is the human viewpoint. (I would add that one can be a materialist yet still presuppose dualism, which is the machine option you note below.)

But both 'ghost' and 'machine' are abstractions or intellectual models; organisms are not machines, and the mind is not a ghost. But having developed that model, or is it metaphor, then scientifically-inclined philosophers sought to eliminate the ghost, leaving only the machine, which is just the kind of thing that lends itself to study and improvement. — Wayfarer

Which still presupposes the dualist framing (with one half eliminated). Naturalism, properly understood, rejects both the ghost and the machine. As an example, think of Aristotle's naturalism which included purpose, ethics, mathematics, and so on.

The way I approach a definition of 'mind' is 'that which grasps meaning'. But mind itself always eludes objective analysis, as it not objectively existent. — Wayfarer

The trick is to avoid reifying abstractions. We can wonder whether Donald Trump has lost his mind. We shouldn't also wonder whether he left it on the kitchen bench next to his car keys.

As Gilbert Ryle put it, "Descartes left as one of his main philosophical legacies a myth which continues to distort the continental geography of the subject. A myth is, of course, not a fairy story. It is the presentation of facts belonging to one category in the idioms appropriate to another. To explode a myth is accordingly not to deny the facts but to re-allocate them." -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectSubstance dualism? On your view, how do Popper and Kuhn presuppose it?

— Andrew M

Because while they may not themselves explicitly refer to the res cogitans or the res extensa, they both discuss knowledge and theory from the subject/object formulation. — Xtrix

Can you be more specific? How does falsifiability and paradigm shift, for example, imply a subject/object dualism?

But perhaps you have a specific thesis with respect to subject/object that you think is basic to (or assumed by) modern science? Perhaps you could give some examples of how it applies.

— Andrew M

In psychology, particularly in studies of perception. It permeates the philosophy of language (Quine's "Word and Object"), cognitive sciences, etc. This way of talking about the "outside world" of objects and the "inner world" of thoughts, perceptions and emotions is literally everywhere. It'd be hard not to find examples. — Xtrix

Fair enough - I agree that dualism has had a significant influence in those areas. But my impression was that it is also commonly thought to be a mistaken view. See, for example, Dennett's Cartesian Theater criticism.

I would note that Quine opposed mind/body dualism. As did the ordinary language philosophers, particularly Gilbert Ryle (in his book The Concept of Mind).

My main area of scientific interest is physics and I'm not aware of any examples there, with the possible exception of the "consciousness causes collapse" interpretation of quantum mechanics. However that interpretation is more of historical interest these days, popular misconceptions notwithstanding. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectI have an interest in Husserl ... ‘Crisis’ maybe? — I like sushi

A crisis in philosophy perhaps, not so much in modern science. :-) -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectPopper and Kuhn are interesting, but themselves presuppose Descartes' ontology. — Xtrix

Substance dualism? On your view, how do Popper and Kuhn presuppose it? -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectAs I see it, the process of 'objectifying' is specific to the modern outlook. — Wayfarer

I don't think so. I think the issue arises due to a philosophical conflict between dualism and naturalism, an issue that exercised pre-moderns as much as moderns. Descartes' mind/body dualism is one manifestation of that. Plato's ideal Forms (as distinct from the shadowy physical world) is an earlier manifestation of dualism.

Even in your apparently simple construction, there's something unstated, which is that 'Bob' is an object for Alice, whereas Alice is an object for Bob. Whether there are objects without subjects, or subjects without objects, is left open. — Wayfarer

On a natural view, there is a relational symmetry between subject and object. We can notice that Bob is hit by a falling branch. Or we can notice that a falling branch hit Bob. The subject and object are interchangeable and the details of the kind of referent that Bob and the branch each are is abstracted away. That is useful for scientific modeling where one might want to consider Bob and the branch as abstract natural systems that can be represented (in language) in a myriad of different ways and for different purposes.

Whereas on a dualist view, subject and object are ontologically distinct and relationally asymmetrical. Science can properly describe objects but not subjects, which are beyond it's purview. On that framing, naturalism overreaches, objectifying subjects and purporting to provide "a view from nowhere". But that is to misunderstand naturalism, which does neither of those things. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectYes, that's a linguistic distinction. That's not what I was getting at, as I feel I've made clear already. — Xtrix

It seems you're asking whether others see things differently from Cartesian dualism and/or Kant's transcendental idealism. And, further, that they seem to provide the philosophical basis for modern science.

I do see things differently from that. Per your second claim, I think Descartes, Hume and Kant all left a mark on how science was subsequently practiced. But in modern times, Popper and Kuhn are probably the main influences (and Positivism before that).

But perhaps you have a specific thesis with respect to subject/object that you think is basic to (or assumed by) modern science? Perhaps you could give some examples of how it applies. -

The Notion of Subject/ObjectI see the as relational antonyms because they’re relational antonyms. Many mistaken them for complimentary antonyms. — I like sushi

Yes, exactly.

I still don’t really understand what is being asked for. — I like sushi

So the ordinary language distinctions seem to have been rejected. The thesis seems to involve an amalgamation of Cartesian substance dualism (and perhaps Cartesian certainty) and transcendental idealism. And an as yet unexplained connection with modern science.

Have I slayed the dragon my quest? — I like sushi

No, you first must venture down the rabbit hole... -

Why x=x ?Actually in that reference you give, Pauli says, ironically, that one should no more rack one’s brains about whether something one cannot know exists at all times, than with the ancient question of how many angels might dance on the head of a needle. — Wayfarer

If we reframe the question to be about photons instead of angels, it turns out an unlimited number can because particles with integer spin, such as photons, are not subject to the Pauli exclusion principle. :-)

Particles with an integer spin, or bosons, are not subject to the Pauli exclusion principle: any number of identical bosons can occupy the same quantum state, as with, for instance, photons produced by a laser or atoms in a Bose–Einstein condensate. — Pauli exclusion principle -

Why x=x ?Thanks. That was the rhetorical point I was working towards. — Wayfarer

Yes, as you know, Mermin was referring to Bell's Theorem which shows that the predictions of quantum mechanics are inconsistent with local realism (where realism, in the sense used here, refers to counterfactual definiteness - the ability to speak "meaningfully" of the definiteness of the results of measurements that have not been performed).

Andrew M

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum