Comments

-

A Nice Derangement of EpitaphsThe first 3 essays in that collection are indispensable. I want to start a thread on the first essay at some point. Especially on the bit about rules and games. Also, the last quote I cited- about saying and showing - is from The Claim of Reason, I should mention. The essay on Endgame is a hilarious takedown of a great deal of analytic philosophy which I love too. The later essays are a bit... meandering.

-

A Nice Derangement of EpitaphsIs there then a way to decide the issue? Is Isaac misusing language, or did he demonstrate an error in Oliver's position? IF what we have is the 'whirl of organism', is there anything more here than simply my preference for Isaac's words over Oliver's? — Banno

One of the reasons I chose the Cavell quote I did (the second one) was because it tries to make quite explicit that 'preference' is not at all what is at stake. To cite again: "What kind of object will allow or invite or be fit for that contemplation, etc., is no more accidental or arbitrary than what kind of object will be fit to serve as (what we call) a "shoe"... You cannot use words to do what we do with them until you are initiate of the forms of life which give those words the point and shape they have in our lives" (my bolding). One way to read this is that what staves off arbitariness here are necessities imposed upon use by our engagements with and of the world: the flip-side of this is what I take to be Davidson's point: what 'controls' the acceptability or not of malapropism (instead of just nonsense) cannot be adduced from some self-contained thing called 'language'. Which, to put it in fun terms that I like, is to say simply that all language is extra-linguistic.

Cavell even employs - in the next section - a nice Wittgensteinian distinction between saying and showing, which I believe you're quite fond of:

When I give you directions, I can adduce only exterior facts about directions, e.g., I can say, "Not that road, the other, the one passing the clapboard houses; and be sure to bear left at the railroad crossing". But I cannot say what directions are in order to get you to go the way I am pointing, nor say what my direction is, if that means saying something which is not a further specification of my direction, but as it were, cuts below the actual pointing to something which makes my pointing finger point. When I cite or teach you a rule, I can adduce only exterior facts about rules, e.g., say that it applies only when such-and-such is the case, or that it is inoperative when another rule applies, etc. But I cannot say what following rules is uberhaupt, nor say how to obey a rule in a way which doesn't presuppose that you already know what it is to follow them.

This 'what cannot be said' is precisely the 'non-linguistic' element inherent in all use of language, and as such, co-constitutive of it. Hence Davidson's conclusion: "we should realize that we have abandoned not only the ordinary notion of a language, but we have erased the boundary between knowing a language and knowing our way around in the world generally". -

Does systemic racism exist in the US?A thought: had Breonna Taylor been hit by all the bullets fired by her murderer, he would not have been charged at all. He was charged, in other words, for not shooting her enough.

-

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?Yeah. This shit is like the idpol of philosophy. Drama for the small minded (not this thread, @Janus - which rightly de-tumored Banno's - but those who like to label and belittle on the basis of said labels).

-

A Philosophy Of Space:up:

There is heaps written on the philosophy of space; Bachelard's The Poetics of Space, Lefebvre's The Social Production of Space, pretty much anything by Doreen Massey, David Morris' The Sense of Space, various writings by Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Ed Casey - the list goes on and on. -

A Nice Derangement of EpitaphsAh, what a wonderful paper. I like all these little read-along threads you do @Banno. They make me go through essays I've been meaning to read but never quite got around to. Well - I've gotten around to this and I've found it perfectly agreeable. Some immediate thoughts:

(1) It's striking to me that Davidson begins from a very similar place to Chomsky (novel grammatical or semantic constructions, to state it broadly) and ends up drawing - to Davidson's infinite credit - an almost diametrically opposite conclusion to Chomsky's waste-of-space linguistics: that language can't possibly be considered in terms of some kind of "general framework of categories and rules", and can only be taken seriously when considered in connection to "wit, luck, and wisdom from a private vocabulary and grammar, knowledge of the ways people get their point across, and rules of thumb for figuring out what deviations from the dictionary are most likely". It's nice too, to finally understand the context for that famous line about how "there is no such thing as language", which I've read a thousand times without going to the source.

(2) The paper immediately brought to mind the work of Stanley Cavell, my favourite philosopher of language (and the only post-Wittgensteinian I trust), who, in probably his most famous lines, concluded thus about language:

"We learn and teach words in certain contexts, and then we are expected, and expect others, to be able to project them into further contexts. Nothing insures that this projection will take place (in particular, not the grasping of universals nor the grasping of books of rules), just as nothing insures that we will make, and understand, the same projections. That on the whole we do is a matter of our sharing routes of interest and feeling, modes of response, senses of humor and of significance and of fulfillment, of what is outrageous, of what is similar to what else, what a rebuke, what forgiveness, of when an utterance is an assertion, when an appeal, when an explanation—all the whirl of organism Wittgenstein calls “forms of life.” Human speech and activity, sanity and community, rest upon nothing more, but nothing less, than this. It is a vision as simple as it is difficult, and as difficult as it is (and because it is) terrifying" (Cavell, "The Availability of Wittgenstein’s Later Philosophy")

The resonances with Davidson here should be obvious (notably, Cavell published this almsot 20 years before Davidson's essay!). And one of the nice things that Cavell provides - which Davidson here only opens as a question - is precisely an account of these features of language in terms of what he calls 'projection'. For Cavell, words (or phrases, in the case of malapropisms) can be "projected" into different contexts, and whether those projections take hold or not (are "acceptable", in the case of malapropisms, or "unacceptable" in those cases where we adduce that someone is just talking nonsense) depends only on our 'forms of life' - the 'whirl of organism'. Some more Cavell, for comparison:

"While it is true that we must use the same word in, project a word into, various contexts (must be willing to call some contexts the same), it is equally true that what will count as a legitimate projection is deeply controlled. You can "feed peanuts to a monkey" and "feed pennies to a meter", but you cannot feed a monkey by stuffing pennies in its mouth, and if you mash peanuts into a coin slot you won't be feeding the meter. Would you be feeding a lion if you put a bushel of carrots in his cage? That he in fact does not eat them would not be enough to show that you weren't; he may not eat his meat. But in the latter case "may not eat" means "isn't hungry then" or "refuses to eat it". And not every case of "not eating" is "refusing food".

... I might say: An object or activity or event onto or into which a concept is projected, must invite or allow that projection; in the way in which, for an object to be (called) an art object, it must allow or invite the experience and behavior which are appropriate or necessary to our concepts of the appreciation or contemplation or absorption... of an art object. What kind of object will allow or invite or be fit for that contemplation, etc., is no more accidental or arbitrary than what kind of object will be fit to serve as (what we call) a "shoe". ... You cannot use words to do what we do with them until you are initiate of the forms of life which give those words the point and shape they have in our lives." (Cavell, The Claim of Reason).

More to say, but just wanted to plonk at least these two thoughts out there for now. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Ah yes, the Animal Liberation Front and Nazis, basically the same*if you're a fucking brainlet.

-

A Nice Derangement of EpitaphsSo I started reading this and to my pleasant surprise it is not written like ass, which alot of (early?) Davidson is. Might finish it!

-

Does systemic racism exist in the US?But the wall that got shot definitely required justice because who the fuck cares about dead black people when private property was harmed? White walls matter.

In case it wasn't already obvious that private property matters more than black lives: it's right there, in the fucking judgement of the law. People need to get it through their thick skulls that this isn't some polemical left-talking point. Private property > black lives. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Perhaps the real problem here is that in a few years whites will be in the minority in the US. More whites are dying than being born. — Punshhh

I always find this point unintentionally hilarious. I mean, gee, would it be like there's something... wrong about... how... minorities... are treated in the US? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)In other news, while American pissants continue to quake in their shitstained boots over fantasies of antifascist violence, Trump supporters are actively planning, with recorded intent, to commit acts of violence and murder among protests:

"Leaked chat logs show Portland-area pro-Trump activists planning and training for violence, sourcing arms and ammunition and even suggesting political assassinations ahead of a series of contentious rallies in the Oregon city, including one scheduled for this weekend. ... [Fascist activists] also claim police cooperation in interstate violence, writing “Yes, going after them at night is the solution… Like we do in other states, tactical ambushes at night while backing up the police are key. You get the leaders and the violent ones and the police are happy to shut their mouths and cameras.” Melchi nevertheless recommends that members disguise themselves to avoid the consequences of homicide. “We must be ready to defend with lethal response… Suggest wearing mask and nothing to identify you on Camera…to prevent any future prosecution.”"

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/23/oregon-portland-pro-trump-protests-violence-texts

Leaks thanks to antifa action. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)American cops routinely shoot people in the back, with their hands up, or even lying down - to mention nothing about their routine use of strangulation of those who are prone. This notion that the multitude of murders they commit are a function of their being scared about people 'resisting' is fariytale horse shit made for dupes.

-

"My theory of..."No, because we are magnanimous.

And also take delight in uh, testing such threads. -

Why special relativity does not contradict with general philosophy?In other words, and contrary to popular simplifications, it says that what is true will be true for all observers. — Banno

So much so that Einstein thought he should have named the theory of relativity the theory of invariance instead.

As for the OP: there is no such thing as 'general philosophy', and even if there was, what reason would there be that SR would contradict it? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Just to be clear: the whole 'resisting arrest' narrative is itself horseshit. While it goes without saying that resisting arrest does not warrant summary extra-judical execution, the overwhelming evidence is that twitchy, terrified, and mentally fragile cops simply murder people for so much as existing in the wrong way - usually for being black in their miserable presence.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Amazing how these small government fuckfaces all of a sudden become cop scrotum fondling simps as soon as it's black people being murdered by them.

The same snowflake cops who are so fragile that they'll have a mental health episode over a McMuffin are supposed to be in a position to rationally judge what is a threat to their lives.

Cops murder people wontonly and the idea that they do so because their lives are at risk is laughable bullshit peddled by authority loving wankers like NOS who want nothing more than to swallow whatever piss the State will dribble down their throats.

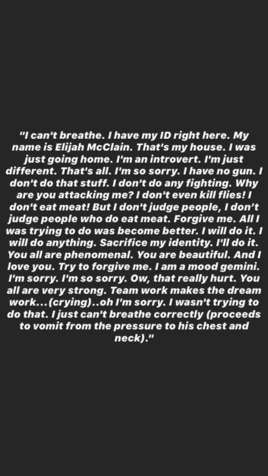

Two words: Elijah McClain. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Check-out every now and then; good for your health.

Also NOS is not a person he's just a kind of jar of living urine. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The village dumpster makes this place more interesting.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)If only Charles Kinsey had complied.

If only Breonna Taylor had, I dunno, shot herself so the cops didn't have to do it for her instead of sleeping or something.

And of course everyone knows that 'not complying' warrants extra-judicial murder on the spot. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Ah the 'liberatrian' cop bootlicker makes an appearance.

No doubt before he praises the head of state for being a great leader of government anytime now. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The rather miserable fact is that cops don't murder black people because they hate them. They murder them because they are indifferent to their lives. One could even say because their lives don't, er, matter. If only there was a movement that has been trying to get this rather basic point across somewhere...

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Does 14 shooting deaths of unarmed black in late June of 2019 constitute an epidemic? — BitconnectCarlos

Lmao now you're just changing the point to something I never said.

How do you get by being so pathetic? -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Right. Now how many black people are there in America compared to white people? And how many white people have been filmed unjustifiably killed? — Kenosha Kid

Don't give him hints, you're spoiling the fun! -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Amazing. You're actually this dumb. I think I'm in love.

I literally used the numbers you quoted in your post (plus a quick google search re: demographic ratio of black::whites).

Or is it that you don't know how to do the calculation?

Either way I'm having the time of my life here :lol: -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)"As of the June 22 update, the Washington Post’s database of fatal police shootings showed 14 unarmed Black victims and 25 unarmed white victims in 2019. — BitconnectCarlos

Ah, so unarmed black Americans get murdered by cops at 3 times the rate of unarmed white Americans, adjusted for population.

Cool and normal. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)The identity politics is strong with this one. :snicker:

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)you cry 'no fair' when a fascist gets so much as a punch in the teeth — Kenosha Kid

seems like a larger criticism towards white people. — BitconnectCarlos

Huh. Nice spontaneous word association.

Nice identity politics too.

See - you're the lesson. You just speak, and all this hilarious shit comes tumbling out. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Antifa terrifies people because they do the exact opposite of virtue signalling. They kick in the heads of Nazis and Nazi cunt sympathizers like NOS, so they need to be painted in as bad a light as possible. It's always the effective ones whom the campaign to smear ratchets up the highest.

Also Andy Ngo already had brain damage, he just found a convenient excuse for it. It would be good if he were to drop dead tomorrow. The world would be a better place. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)No no, I quite like people like you dwelling in your ignorance and hypocrisy in public - the instructive lesson is you, my darling.

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Yeah I dunno why anyone expects people like Bit to need to know pesky things like 'facts'. The media he swallows like so many unborn babies have told him that they are bad, so, they are bad.

And of course, these shitsticks will want to wait until people are in ovens before they may get an inking of the fact that hey, maybe we should have done something about the fascists before we got to this point.

It's not like Americans are scooping out the reproductive organs of those housed in concentrations camps or - no, wait, that's exactly what they're doing.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum