Comments

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§74

§74 expands on the theme of understanding-as, this time tying it to the question of perception: the question of 'seeing-as'. In fact, part of what's at stake in §74 is drawing a certain kind of equivalence between seeing-as and understanding-as. A puzzle I'd like to draw out is: why this equivalence? And the clue is in the fact that Witty says that seeing-as does not imply seeing differently; [re-ordering slightly]:

§74: "It is not so ... that someone who views this leaf as a sample of ‘leaf shape in general’ will see it differently from someone who views it as, say, a sample of this particular shape".

By which I understand that the leaf will not look different, in terms of specular quality, to two different people who see the leaf-as-X in different ways [sample or general schema]. So if seeing-as differently does not mean that the leaf looks different, what does it mean? Witty's answer, as ever, turns upon how different roles imply different uses:

§74: "someone who sees the leaf in a particular way will then use it in such-and-such a way or according to such-and-such rules".

To which we might add something like: someone who sees the leaf in a different particular way will use in a different such-and-such way, etc. Note that by emphasizing use in this way - the fact that the same thing, seen-as differently, will in turn be used differently in corresponding games - Witty ends up doing something really interesting with perception: he makes it less about the sensorial, qualitative/raw 'feeling' aspect of it ('qualia', etc), so much as incorporates perception as having a part to play in intelligibility. The role of the perceived in Witty's account of intelligibility has less to do with the sensory than the grammatical(!), of all things.

This is something Witty will expand upon at length in later sections, but here I just want to note that this helps us answer the 'puzzle' I set out at the beginning - the equivalence of understanding and perception. By modelling, as it were, the latter on the former, Witty aims to once again 'de-interiorize' perception - just as he did with the memory-image in §56/57. Just as, in §56/57, the importance of the memory-image had to do with its role in a langauge-game, so too does perception's importance come out in the role it also plays in an economy of use:

§74: "Whoever sees a sample like this will in general use it in this way, and whoever sees it otherwise in another way." -

Monism1)What do you mean by 'idealizing one part of reality over others?'

2)What makes something 'extra-real'? — csalisbury

I wanna say that exactly how these are cashed out depends on the idealism in question. A certain reading of Plato, for example, reserves what I called 'ontological heft' exclusively for the Intelligible Forms, with the sensory world just being kind of like a derivitive run-off (idealization of forms - 'overmining', forms as 'extra-real'); or, on the flip side, you get certain 'materialisms' that reserve such heft only for 'atoms' or some kind of fundamental stuff, with everything above that scale similarly being just so much ephemera (idealization of simples - 'undermining', atoms as 'more real' than everything else).

This can also be cashed out at other, less explicitly philosophical levels at well (Politics: there is only the individual; Biology: the gene is the only thing that matters). All of these are just so many variations on an (idealist) theme. So the point is that there's no 'one way' in which something is idealized or designated as 'extra-real'. Perhaps you can call the above 'schemas' for idealisms.

--

As an aside, I have no interest in letting questions of 'consciousness' - a cosmic party trick of disproportionate interest - overdetermine this conversation. -

MonismBut why not materialism? This seems evasive, but to build off your mention of a vulgar materialism - why must materialism always be vulgar? Is there no room in the house of materialism to accommodate the world such as it is?** And why not? What is it about materialism that would not allow this kind of in-corp-oration?

Which is not to say that it isn't a rhetorical device or even a provocation - only that it's not only those things. And then there's that part of me which is suspicious of any 'beyond X and Y', which smells a bit too much of 'third way' politics, which always ends up being one of the previous offerings in disguise.

**It might be fruitful to ask this question of idealism in order to triangulate positions here - and I think, if asked of it, the answer has to be 'no': the whole point of idealism (in my understanding of it), is that it by definition aims to idealize one part or parts of reality over others (or, using a different topology, aims to idealize an extra-reality over reality). Which leads a bit back to the question of monism - if idealism and materialism both need to 'exclude' something to define themselves by, idealism 'excludes' parts of the world in favour of others (undermining/overmining), and materialism excludes attempts at exclusion, which is why the logic of the not-all, the double negative ('there is nothing is that not...') fits nicely I think with a materialism (part of what I'm trying to do is set up an 'asymmetry' of exclusion - both exclude, but in different ways).

Does that work for you? -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.It’s been a bit since I posted in here last, but I’d like to pick up where I’ve left off and try to catch up! Brief recap: we’re in a section where Witty is inveighing against the idea of analysing things into component parts. In particular, Witty has turned his attention to the notion of similarity, and exactly how - if at all - one is able to specify the similar.

§73

§73 can be read as something like an ‘application’ of Witty’s argument so far. If §71 tired to show that ‘blurred concepts’ like ‘stay roughly here’ did not resolve into any further specificity upon analysis (where ‘analysis’ ought to be taken as the the opposite of synthesis: breaking apart into pieces, as opposed to putting together), §73 turns its attention to the ‘ideas in our head’ when we think of certain things. The question, as with §71, is something like: how specific does such an ‘idea' have to be? Witty answer is basically that it doesn’t have to be specific at all: it can be a ‘general’ leaf, a 'schematic’ leaf without all the details ‘filled in’ as it were. Just as ‘stay roughly here’ can also be understood as something like a general schema without 'in-built’ particularity.

The second half of §73 brings back the question of roles, although the word is not uttered as such: Witty speaks instead of 'understanding as’ (as in, to understand X as Y), which can be read as ‘to understand X playing the role of Y’ (in a language-game Z)'. The series of rhetorical questions which close off the section -

“What shape must the sample of the colour green be? Should it be rectangular? Or would it then be the sample of green rectangles?- So should it be ‘irregular’ in shape? And what is then to prevent us from viewing it a that is, from using it a only as a sample of irregularity of shape?”

- attests again to the fact that the 'same thing' can play different roles, and that there definitive answers to these questions can only be sought in relation to particular language-games: there is no 'general theory’ that would satisfy these questions in advance. One must ‘look and see’, ‘up close’ to get answers to these question. So rigorous is this that for Witty, even to understand a schema as as schema (and not as the shape of a particular leaf) ‘resides in the way the samples are used’. i.e. their role in a game. -

Monismwhy is this 'materialist'? — csalisbury

(sorry for late reply)

I suppose I could give you Zizek's answer or I could give you mine. Zizek's is a whole thing about the subject, and how it the not-all bears witness to the inclusion of the subject into any picture of reality etc etc. I could go into exegesis but that's less fun. So, my take-away: I think the not-all enables us to think in terms of a 'non-reductive' materialism. To explain: what I'm always looking for is something that avoids two poles, a kind of scylla and charybdis thing: (1) No privileged ontological stratum (atoms, simples, 'stuff', out of which everything else is made, and is 'epiphenomena' in relation to that stuff); (2) No 'higher reality' over and above 'this' one: no Ideas waltzing in from heaven to in-form all the passive stuff lying around in wait for it.

To borrow the vocabulary of Graham Harman, I neither want the world to be undermined (from below), nor overmined (from above): it want it 'such as it is', and no more (or less). The not-all gives me this, or rather, helps fulfil both conditions. That’s ‘my’ understanding of materialism at any rate: the effort to give ontological heft to each and every thing, such as it is, without ideal-izing any part of reality or ‘beyond-reality’ over and against another. -

Society and testiclesIdk there's a delicious irony in the fact that manhood is associated with a pair of fragile little dangly, shrively things. And everybody - men and women - has a pained giggle when someone gets kicked in the nads. It the taboo and the sacral made comic and pedestrian.

-

What is trueThe only tool we have available to provide support or not for the truth of anything is application of the scientific method. — Scribble

And which scientific test would you subject the truth of this claim to? -

Currently ReadingLudwig Wittgenstein - Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics

Ludwig Wittgenstein - Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics

Whadya think? -

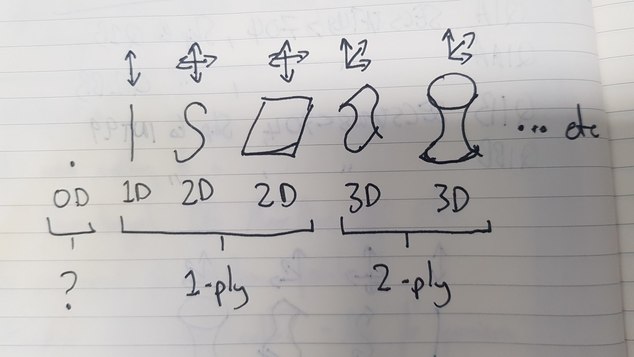

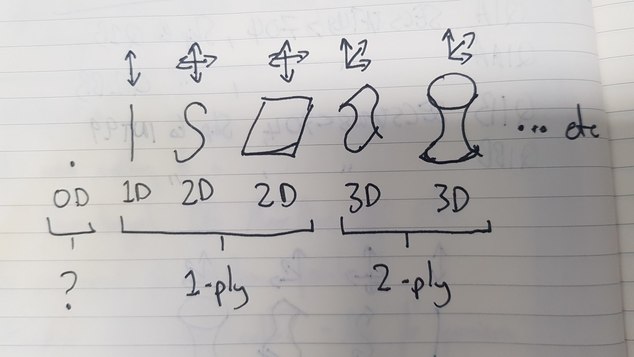

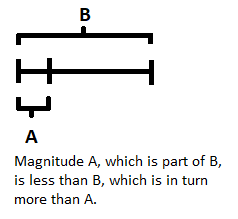

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupOkay, I think I know where I got confused: in my attempt to distinguish between dimensions and n-ply magnitudes, I conflated certain things. For instance, rectiliear and curviliear lines: rectilinear lines are 1D, and curvilienar lines are 2D, but as far as treating them as manifolds is concerned, there is no real difference. So this doesn't map neatly on my attempt to simply specify that n-ply variables are always one degree 'down' from a dimension. I made a similar conflation between extended S-curves and the vase - I thought the vase would be a +1 degree manifold over a S-curve, but I was wrong about that. So. Here's a diagram I drew:

Does this look right?

I'm still confused about the OD point: does it count as an extended magnitude or not? -

If there was an objective meaning of life.Originally posted by @Paul24, merged into this thread:

"Hello everyone,

Today I would like to discuss with you a very delicate but interesting subject that have been on everybody's mind since the beginning of mankind. The purpose of life. So I wanted to ask you this. What is the purpose of life? I tend to agree with the premise that there is a purpose to every form of life from microscopic beings to macroscopic ones. This brings me to my second question : should life exist without purpose? Let me explain a little bit. Life is a cycle and everything in it contributes in order to maintain the universal order of things. Can life exist without purpose? I do not think so but I'm open for debate.

I await your reponses with a lot of curiosity.

Sincerely,

Paul" -

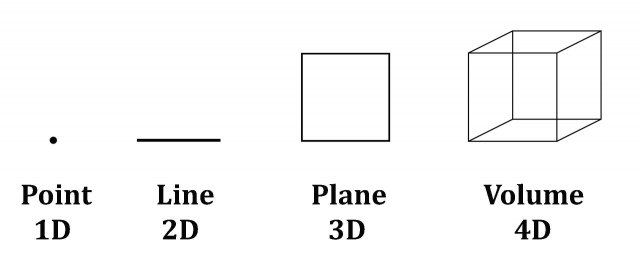

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupOne thing that I've taken for granted in the above presentation is the fact that dimensions are always 'one number higher' than n-ply extended magnitudes. So a 2D line corresponds to a 1-ply extended magnitude, a 3D plane corresponds to a 2-ply extended magnitude and so on. Again, as fdrake points out, this difference is vital. In a Cartesian coordinate system, a point is specified by as many variables as there are dimensions. I.e:

Point P is specified by 3 variables, x, y, and z, corresponding to each of the spatial dimensions of the coordinate system. If, however, point P were to be part of a 2-ply extended manifold (which, remember, corresponds to a 3D plane), one would only need 2 variables, and not 3. And the reason this is so, is that the measure of the magnitude is no longer extrinsic to the surface (like the Cartesian coordinates), but immanent to it. This also has to do with why the measure of magnitude starts with a curve (a line is species of a curve, btw), and not a point. Only a curve can have a magnitude, which is why n-ply magnitudes are always one number 'down' from a dimension. -

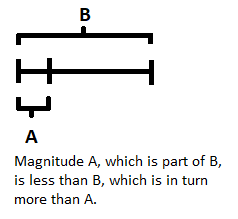

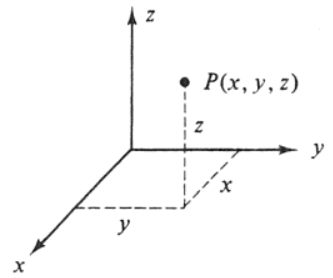

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupHard to add to what @fdrake already laid out for §2, so maybe just a bit of 'how Streetlight intuits it' kind of thing. So, my approach has been to think of an 'extended magnitude' as something like a 'shaped dimension' - a dimension with a shape. In fact, we can begin with dimensions and use them to think n-ply extended magnitudes. So here's a nice image I found illustrating dimensions:

This kind of thing should be relatively familiar with most people. Now, ignoring the 1D point (which doesn't have a magnitude or size), a 1D extended magnitude actually corresponds to the 2D line: the line is the most basic 'extended magnitude' along which one can move backward and forward along. Now, add another dimension (the 3D plane) and you have a doubly (2-ply) extended magnitude. Add yet another, and you have a triply (3-ply) extended magnitude and so on, for all dimensions N - hence, n-ply extended magnitudes. 'Adding dimensions' is what Riemann refers to as a manifold 'passing over into another entirely different manifold in a definite way'.

The only thing to add to this is that extended magnitues, unlike the 'dimensions' we're used to speaking about (pictured above) don't have to be straight. They can be bendy. Or to use a more technical vocabulary, they don't have to be rectilinear, they can be curvilinear, like fdrake's illustrations. So if you begin with a bendy 1D extended magnitude (a curvy line), you can 'pass over' into another magnitude by rotating the curve. From the fdrake's Wiki link:

This is a 1-ply extended magnitude (a bendy 2D line) 'passing over' into a 3-ply extended magnitude (a 4D Volume). This 'skips' the 2-ply extended magnitude because we're rotating the curve, rather than just 'stretching it out' along a single dimension, like was done in fdrake's post. -

MonismBut what does this way of saying 'not that' really mean, effectively, other than that you can be a materialist, without having to ever say firmly what that means? And with the permission to add whatever kludges you want without having to forfeit your 'materialist' mantle? — csalisbury

Two points to make I guess. First is that I invoked the 'not-all' Logic to diffuse the general question of monism asked in the OP, irrespective of the 'content' of that monism ('mind', 'matter', etc). I think you're cool with this. The second point bears on Zizek's more specific argument w/r/t materialism and the answer to this is that the fact that reality is not-all is the 'content' of Zizek's materialism: for Zizek, to be a materialist is to claim that reality is not-All ('ontologically incomplete', as he puts it sometimes as well), or in yet a third formulation, that there is no big Other.

This answer is 'Zizek specific' btw, insofar as his particular brand of materialism is premised on 'short-circuiting' both form and content. A different brand of materialist would probably have to answer your charge of 'ok but where the positive content?'; Zizek, because he simply identifies the not-All with reality as such, isn't compelled to do so in the same way. -

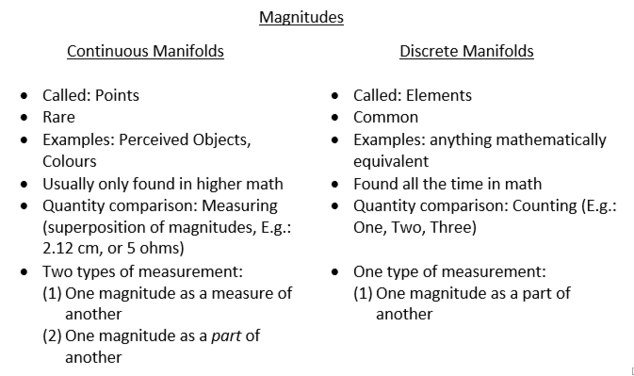

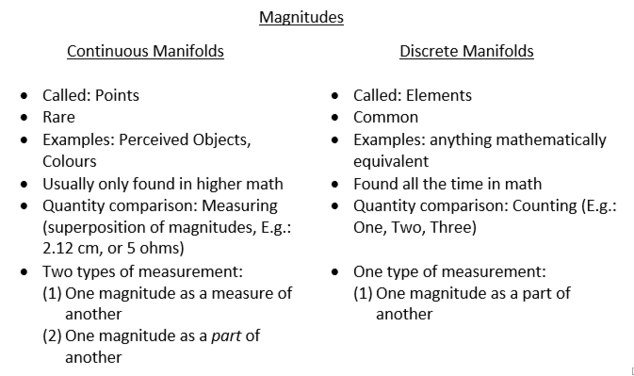

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupTabled summary of §1:

(Ahh, I messed up the last bit of this table: the type of measure for discrete manifolds should be one magnitude as a measure of another, not as part of another. I copy-pasted the wrong text!).

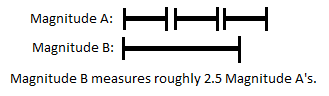

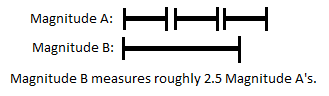

Now, the tricky thing is to understand the two types of measurement for manifolds. I think a visual representation will be helpful:

(1) Superposition of magnitudes:

(2) One magnitude as part of another:

It is this second form of measurement, conducted on continuous manifolds which cannot be superposed, which "forms a general division of the science of magnitude in which magnitudes are regarded not as existing independently of position and not as expressible in terms of a unit, but as regions in a manifoldness." The language in this is a bit archaic, but a 'general division of the science of magnitude' can be translated into something like "this kind of measurement is one kind of measurement in a larger 'science of measurement' which also includes other kinds of measurement".

Note the two conditions of this kind of measurement:

(A) The magnitude cannot be regarded as independent of position (within the manifold).

(B) The magnitude is not expressible in terms of a unit.

Which one can summarise as: the measure of a magnitude of this kind is immanent to the manifold itself, and not extrinsic to it. Gonna include a quote from Manuel DeLanda which I find very helpful in explaining in why this kind of thing is novel in math:

"In the early nineteenth century, when Gauss began to tap into differential [mathematics], a curved two-dimensional surface was studied using the old Cartesian method: the surface was embedded in a three-dimensional space complete with its own fixed set of axes; then, using those axes, coordinates would be assigned to every point of the surface; finally, the geometric links between points determining the form of the surface would be expressed as algebraic relations between the numbers. But Gauss realized that the calculus, focusing as it does on infinitesimal points on the surface itself (that is, operating entirely with local information), allowed the study of the surface without any reference to a global embedding space. Basically, Gauss developed a method to implant the coordinate axes on the surface itself (that is, a method of “coordinatizing” the surface) and, once points had been so translated into numbers, to use differential (not algebraic) equations to characterize their relations. As the mathematician and historian Morris Kline observes, by getting rid of the global embedding space and dealing with the surface through its own local properties 'Gauss advanced the totally new concept that a surface is a space in itself'.

The idea of studying a surface as a space in itself was further developed by Riemann. Gauss had tackled the two-dimensional case, so one would have expected his disciple to treat the next case, three-dimensional curved surfaces. Instead, Riemann went on to successfully attack a much more general problem: that of N-dimensional surfaces or spaces. It is these N-dimensional curved structures, defined exclusively through their intrinsic features, that were originally referred to by the term “manifold”. Riemann’s was a very bold move, one that took him into a realm of abstract spaces with a variable number of dimensions, spaces which could be studied without the need to embed them into a higher-dimensional (N+1) space" (Delanda, Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy).

--

The end of §1 basically tries to say why this kind of measurement is so important: it allows one to make good on certain mathematical advances by Abel, Lagrage, etc, and it allows for a fuller investigation of multiply extended manifolds. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.If you guys and gals want to speak of 'applying Wittgnestien', here's what could be a fun exercise. With respect to the current sections of the PI that we're reading, what is wrong with this OP?:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/4917/is-cell-replacement-proof-that-our-cognitive-framework-is-fundamentally-metaphorical

Maybe an opportunity for @Banno to chime in. -

Just curious as to why my post was deletedWhat do you mean "if you're who I think you are? — Janis

I just mean I can't see deleted posts so I'm working off memory here - and that if I recall, your OP was something like "I have some papers written by someone else that are pretty neat. If there's enough interest I might make some of it available" - paraphrasing, of course. And that sort of stuff is a no no. Anyway, I'll leave it to whoever in fact deleted it to provide a better explanation than I can. -

Just curious as to why my post was deletedIf you're who I think you are (or rather, if that post was what I think it is), I didn't delete it, but I believe the idea is that no one is here to play games, and if you're going to post something, post it, and not play peek-a-boo with your OP.

And books and papers are allowed if the ideas in them are discussed enough to spark a thread on its own terms. In other words, you need to do a bit of work of your own here. Posts that just say things like 'read this its great' have a good change of being deleted. -

How do you get rid of beliefs?"Get it into your head that, if you are unable to believe, it is because of your passions, since reason impels you to believe and yet you cannot do so. Concentrate then not on convincing yourself ... but by diminishing your passions. You want to find faith and you do not know the road. You want to be cured of unbelief and you ask for the remedy: learn from those who were once bound like you and who now wager all they have. These are people who know the road you wish to follow, who have been cured of the affiiction of which you wish to be cured: follow the way by which they began. They behaved just as if they did believe.

...That will make you believe quite naturally, and will make you more docile. 'Now what harm will come to you from choosing this course? You will be faithful, honest, humble, grateful, full of good works, a sincere, true friend ... It is true you will not enjoy noxious pleasures, glory and good living, but will you not have others? I tell you that you will gain even in this life, and that at every step you take along this road you will see that your gain is so certain and your risk so negligible that in the end you will realize, that you have wagered on something certain and infinite for which you have paid nothing."

Pascal's advice. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupI'm not sure when we're supposed to start, but I was reading the introduction to the Riemann paper and was making notes, so I figure I'll do a quick post on the 'Plan of the Investigation' section in case it helps people orient themselves.

The basic idea is this: Riemann is saying that space as we know it - the kind of space in which me move around and live - is but a particular case of a more general notion of space which can be constructed from 'general notions of magnitude'. Or, put the other way, one can construct more kinds of spaces out of 'general notions of magnitude' than only the kind of the space in which we live in.

To this degree, the 'general notions of magnitude' are too general to properly model (our) space: if you begin with such general notions and nothing else, you won't be able to properly model our space with enough specificity. So to such general notions, one needs to add another ingredient: 'experience'. Hence:

"The propositions of geometry cannot be derived from general notions of magnitude, but ... the properties which distinguish space from other conceivably triply extended magnitudes are only to be deduced from experience".

So Riemann here develops a tension between general notions on the one hand and experience on the other, the latter of which includes 'matters of fact' (a kind of rationalism vs. empiricism dichotomy). And each 'side' has its own issues when it comes to space. On the 'side' of the rational, general notions are 'too general' to get at the specificity of space, and on the side of the empirical, 'several systems of matters of fact' can be used to 'determine the measure-relations of space'.

Or to put it differently, if there is a one-to-many relation between general notions of magnitude and our space (the general notion can give rise to many notions of space, of which ours is only one), there is, on the other hand, a many-to-one relation between 'systems of matters of fact' and our space (several systems of matters of fact can give rise to our space). That all said, the main 'system of matters of fact' has so far been Euclidean geometry (there can be others).

So given that there is no one-to-one correspondence between 'matters of fact' and our space, Riemann wants to ask after the 'probability' of such matters of fact - which I understand to be something like 'how probable is it that these matters of fact obtain, and not others?'. And also, given that we can go 'beyond the limits of observation', both at the level of facts and at the level of notions, how 'justified' would we be in doing so? Which I read as something like: 'is there any good reason to 'go beyond the limits of observation' and indulge in what we 'can' do over what 'is'?

I'm a bit iffy on my reading of this last bit, and am keen to see what others make of it. This bit: ""we may therefore investigate their probability,which within the limits of observation is of course very great, and inquire about he justice of their extension beyond the limits of observation, on the side of both the infinitely great and of the infinitely small". -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§70

§70 continues to emphasise how boundaries (read: rules) are inessential to the workings of concepts (to the concept of concepts, if you will). This is, as I mentioned earlier, analogous to the claim that the analysis of composites into simples is itself inessential for the composites to function as composites. In §70 this is cashed out in the claim that language works perfectly well without the need for definitions - hence the rhetorical question: "do you want to say that I don’t know what I’m talking about until I can give a definition of a plant?” (Witty's answer is clearly: “Obviously not”).

As usual however, Witty leaves space for boundaries to nonetheless have a place, where, in conceding to his imaginary interlocutor that the picture of the leaves is not ‘exact’, it is only not ‘exact’ in the particular sense that his interlocutor wants. Which means of course, that ‘exactness’ is only as specific as what is demanded of it. Which itself explains the closing of §69: "Though you still owe me a definition of exactness”.

§70 [Boxed Note]

The question sustained in this is something like: is the understanding of not-a-gambling-game ‘contained’ within the imperative to ‘show the children a game’? Or in other words: does the compound ‘show the children a game?’ ‘contain’ within it the simple ‘not a gambling game’? Or is there always an irreducible gap between the two, so the the complex cannot be so straightforwardly resolved into the simple. I’m not sure the question Witty asks here is really ‘meant’ to be answered - it’s meant to simply keep alive that dissonance between complex and simple.

—

I was going to write something about §71, but the whole thing is straightforward enough, so I’m going to skip it.

—

§72

§72 doesn’t so much make a point as set a scene for what’s to come: its a question of finding what is common (a color) in (1) A series of multicolored pictures; (2) Various shapes of the same color; (3) Various shades of blue. In all these cases, the question to keep in mind is something like: how does one pick out similarity among these difference cases of difference? Note also how the question of ostension is creeping its way back in here. -

MonismTo be honest, I've tried to read into this and I still haven't found a satisfactory answer beyond 'because Freud was a Victorian'. I'm sure someone better versed in psychoanalysis could offer some kind of lovely sophisticated answer, but the only codicil I can really offer is that both the feminine and the masculine (and not, note, male and female) are - in Freud as for Lacan - responses to an original 'failure' of symbolization: both 'unity' and 'multiplicity' are (productive) failures: jury-rigged responses to something not working well to begin with.

-

MonismThough maybe you could have a positive claim along the lines of what fdrake's saying, if I understand him. Like maybe the one thing that you could say is that everything that is is capable of having an effect. — csalisbury

Yeah, it's pretty delicate, and my use of positive/negative isn't quite on the mark, because a constraint can well be understood as a positive claim anyway. Perhaps a better distinction might be something like nominal vs. operational - as in, it's all very good to call something a substance out of which everything 'is' (Mind, Matter, res extensa etc), but the meat of any such distinction is what such a substance can do that another substance can't. This is the usual: what difference does the difference make?

With respect to the conversation between you and @fdrake, part of my initial response was motivated by trying to rephrase Lacan's logic of the ('feminine') not-all: 'there is nothing which is not...'; which is set against what he calls the 'masculine' logic of universality: 'everything is...'' - the latter being a claim of identity (X=...), while the former leaving the identity of X somewhat indeterminate, and simply 'qualifying' it in some way. Also, as I was reading a bit to formulate this very paragraph a bit better, I realized I more or less borrowed wholesale from a Zizek discussion of this very topic (I kinda had this at the back of my mind when I wrote the initial response, but only dimly! ... Went searching and hey -) :

"The statement "material reality is all there is" can be negated in two ways, in the form of "material reality is not all there is" and "material reality is non-all:' The first negation (of a predicate) leads to standard metaphysics: material reality is not everything, there is another, higher, spiritual reality. As such, this negation is, in accordance with Lacan's formulae of sexuation, inherent to the positive statement "material reality is all there is": as its constitutive exception, it grounds its universality. If, however, we assert a non-predicate and say "material reality is non-all;' this merely asserts the non-All of reality without implying any exception - paradoxically, one should thus claim that the axiom of true materialism is not "material reality is all there is;' but a double one: (1) there is nothing which is not material reality, (2) material reality is non-All.'" (Less Than Nothing)

:cool: -

Naming and Necessity, reading group?Yes. And that is a fact about Nixon. Indeed, we can only posit that he might have had a different name because we can refer to him with the rigid designator "Nixon". How could we make sense of "The man named 'Nixon' may have had a different name"... Only by indexing it to the actual world: "The man who in the actual world is named 'Nixon' might have been given another name". That sort of index is implied by the very shared language we are using for this conversation. — Banno

If people can get this, they can get Kripke. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§69

§69 does some clarification work about the role of boundaries with respect to games (which we can also read as: 'rules with respect to language-games'). As with §68, the point is that the inability to exhaustively 'draw boundaries' around games is not some kind of incapacity or 'ignorance'. We are not failing at something that could, in principle be done - if only we were more intelligent, had better powers of conceptual discernment, etc etc. That we "can't tell other exactly what a game is ... is not ignorance".

And yet again, Witty iterates that this in turn does not mean that boundaries cannot be drawn: "we can draw a boundary - for a special purpose." - but we don't need such a boundary for us to understand what a game is - unless we have a 'special purpose' in mind for it: "Does it take this to make the concept usable? Not at all! Except perhaps for that special purpose". To summarize in point form:

(1) Games (and concepts/words) are not necessarily exhausted by their rules/boundaries.

(2) [Which means]: An inability to exhaustively define a game by means of rules/boundaries is not a deficiency on the part of us or the concept of games.

(3) Which doesn't mean we can't draw boundary if we want to for the sake of some purpose.

---

Since this is a small section, I wanna take the opportunity to go over the motivating context of these remarks. Specifically, it's important to keep in mind the discussion in §60-§64, about whether or not we should 'analyse' compound things into simple things. Recall there that while Witty said that lots of compound things (like broom) could be 'analyzed' into simple things, certain aspects of the compound could be lost in the analysis into simples. So we can't take for granted that the analysis of compounds into simples is guaranteed a priori as an unproblematic operation.

The questions dealt with here are of a similar problematic: can makes be 'analyzed' into their rules? Is there a straightforward, 1:1 correspondence between a game and rules/boundaries that 'compose' it? (just like: is there a straightforward, 1:1 correspondence between a compound and the simples that 'compose' it?). If the discussion of simples and complexes are anything to go by, the answer will be: not necessarily. -

MonismOne way to make sense of 'everything' claims is to treat those claims not as substantive, but as formal. That is, to say something like 'everything is X' is to say that whatever 'there is', 'it' abides by such and such rules, or exhibits such and such properties, and not others. I say this is 'formal' and not 'substantive' because 'everything' here does not designate some kind of positive substance (res cogitans vs. res extensa), but a set of constraints or limits that are operative regardless of the 'stuff' in question.

One interesting implication of thinking this way is that that the order of intelligibility must outrun the order of actuality: we can think more things than there are in the world, and an 'everything' claim is a claim about how we think about the world, placing limits not on the world, but on our thought about it. I suspect the apparent 'paradoxes' of the OP are what happens when claims are made to be about the world itself. Larger point here about how all claims are claims about intelligibility, but that's maybe beyond the scope of this. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.I find the current sections so iconic that it is difficult to provide a summary and not to simply quote them in their entirety. — Luke

I largely agree with this, especially with §66 and §67, which are about as clear as Witty gets. So on to

§68:

The first thing that stands out about §68 is that it harkens back to an early early discussion back in §3, in which Witty was objecting to Augustine that his conception of language held true only for a "narrowly circumscribed area", and in fact then expressly invoked games as a further example. To recall:

§3: "It is as if someone were to say, “Playing a game consists in moving objects about on a surface according to certain rules...” - and we replied: You seem to be thinking of board-games, but they are not all the games there are. You can rectify your explanation by expressly restricting it to those games".

In §3 it might have seemed as though what was missing was a more complete or more general conception of a game. §68 in fact makes clear that this is not the case - the problem isn't that there ought to be a more complete conception of a game, but that no such complete or general conception could be forthcoming, even in principle. Instead, what can count as a game has, as it were, an indefinite extension, which can nevertheless be made provisionally definite by 'drawing a boundary'. Such a boundary will not exhaust what counts as a game, but will, like Augustine, 'circumscribe it' within a certain area.

One 'technical' note here is that §68 marks the reappearance of 'rules' as an object of discussion (they've been 'missing' since §54). With respect to them, the point made seems to be something like: rules function as constraints - they mark, like 'boundaries', lines beyond which one cannot go, without for all that exhausting the range of what can be done within a game. Hence: "No more are there any rules for how high one may throw the ball in tennis, or how hard, yet tennis is a game for all that, and has rules too." -

What is the difference between petitio principii and a transcendental argument?"Charles is a good person because he helps the needy, and anyone who helps the needy is a good person" — Nicholas Ferreira

Hmm, this isn't a petitio principii. The major premise may not be sound, but there's no logical fallacy being committed here:

P1: Anyone who helps the needy is a good person.

P2: Charles helps the needy.

C: Charles is a good person.

Perfectly valid. Maybe not so perfectly sound.

Ironically, your example of a transcendental argument ('I think therefore I am') would count as a PP, insofar as the premise does contain its conclusion - the 'I' (things are in fact more complicated with Descartes, and strictly speaking this is an enthymeme which means that it's missing a stated premise which would complete the syllogism and make this a proper TA but we can ignore all that for the sake of argument).

In any case, while you're right that both share a reliance upon certain assumptions, the kind of thing that is assumed in both are different. In a petitio principii, a conclusion is assumed in the premise. That's just the definition of the PP. A good transcendental argument however, 'assumes' a conditional: Iff X, then Y (or reversed: X iff Y). And I put 'assumes' in quotation marks because the soundness of this conditional itself ought to be something argued for, which means that a TA should, ideally, form one part of a larger argument rather than subsisting alone, unlike a straightforward syllogism. A 'bad' TA, which assumes its conditional without further argument, may indeed fall into PP territory.

The thorny parts of a TA deal with issues of necessity and sufficiency: is X both sufficient and necessary to guarantee Y (and thus fulfil the conditional, which would in turn complete the TA?); These are not really questions which arise with a PP. There's alot more that can be said, and the details of TAs can get real complicated real fast, but hopefully this goes some way to show why one can't straightforwardly identify TAs with PPs. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Yeah, it's no accident that that Witty reprises the vocabulary of the TLP when he speaks of the 'general form of the proposition' - italicised in the PI - only to repudiate it in the latter book. This is one of the more clear moments of discordance between the two Witty's.

-

What is the difference between petitio principii and a transcendental argument?Perhaps you can explain why you think they are similar, to begin with. Show your understanding.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§65

§65 serves as something like a transitional discussion, which both picks up from the previous section (i.e. sections §46-§64), and serves to introduce a new line of inquiry. If §51 implored us to look at what happens 'in detail' across various cases, and if §53 spoke of 'various possibilities' of how language-games make signs correspond to things, and if alot of the discussion so far has been iterating through the various and variable roles that words and can take on in language games - in short, if what has been so far focused on is difference and variety, §65 begins to broach the question of similarity - it asks about the 'general form of the proposition', and of what can be said about this general form (of which, one imagines, the various 'cases' have been 'species', as in genera-species).

And to this Witty simply says: there's nothing invariant across all the different cases taken under consideration so far - there are 'affinities', but not some hard core in common between them all. The proceeding discussion will elaborate on this. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.So what was the point? I just don't get it. — Isaac

The fun is in the exercise, not only the results; each section is like a math problem - the answers are probably out there - in the back of the book, as it were - but the exegetical engagement 'from within' is - for me anyway - alot more intellectually stimulating and rewarding. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§61-§64

§61-§64 is an extended discussion about the difference and/or similarities between the two ways of playing the ‘game’ set out at the end of §60. I’m going to treat these sections together. To recall, the game is one in which either (1) only composites have names; or (2) only parts have names and the composites are described by means of them.

Without getting too far into it, Witty basic point seems to be: the two ways of playing the game can be identified, but it is not necessary that they are. As per his modus operandi at this point, Witty makes their identification hinge upon a conditional: if certain conditions hold, then they can be identified. If not… well, there’s no reason to assume the identity of the two ways of playing the game. As to what conditions these might be, Witty basically leaves this open - those conditions cannot be specified in advance. They’re the sort of thing that require examination ‘close up’ (§51).

That all said, Witty does make the stronger point that it is important not to make any assumptions about the identity of the two ways of playing the game: doing so might ‘seduce us’ (§63) into thinking that (2) is a ‘more fundamental form’ of (1), playing an explanatory role with respect to it. But this ought to not be the case if any attempt to identify the two ways of playing the game is conditional upon certain conditions holding. Basically, its important not to be ‘seduced’ into thinking in the manner of §46 - the passage of the Theaetetus - where simples always serves to explain composites.

Note, in this connection, how a great deal of the preceding discussion between §46 and now has been about actually qualifying Socrates’ statement (in a way that changes its status drastically): yes there are some cases in which simples cannot be ‘further analyzed’ (the Paris rule is neither a meter not not a meter long; red neither can be said to exist or not exist), but this is the case only if (conditionals again!) those simples play particular roles in particular language games. The conditioning here is grammatical (and thus revisible) and not metaphysical (and thus fixed), as it were. Hence why §64 ends by simply arguing that the two ‘ways of playing the game’ can in certain circumstances simply correspond to different language-games altogether (one in which the ‘simples’ have different roles in each, I imagine).

Anyway, if what I’ve written here has the flavour of a summary, it’s because I think these parts serve to ‘end’ the discussion simples and composites began in §46. So, zooming out so far the PI has covered something like:

§1-§27: Imperatives (block! slab!)

§28-§36: Demonstratives (this, that)

§37-§45: Names (Nothung, Mr. N.N.)

—

§46-§64: Linguistic Roles (Simples, Composites, and Iterations thereof) -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.I think that this reading actually brings to completion a line of thought that Witty himself only half finished in §58, because he got caught up in a different but related 'second' line of thought relating to the 'contradictions'. My feeling is that there are two intertwined lines of thought in §58, one more clear than the other, which is yet another reason it's so confusing.

The first line, one I think I brought out above and more clearly articulated by Witty, is that of the pendular movement between claiming 'red exists' = 'red has meaning', and the rubbishing of this claim.

The second line is the one both Luke and you are bringing out, which is the limited linguistic scope of a phrase like 'red exists', which only makes sense in a certain context - much like the claim about the length of the Paris rule. This helps alot in understanding the motivation behind the otherwise curious argument in the first line of thought.

Good stuff! -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Okay okay okay wait I think I understand the movement of the passage: here’s something that struck me while reading your replies and §58 again: the reason the section is such a bitch to read is that Wittgenstein is trying to make sense of a statement that he starts off admitting makes no sense!

The ‘steps’ in the argument are kinda like this:

(1) “Red exists” makes no sense [opening statement, in quotation marks].

(2) [Unstated]: Therefore, we shouldn’t even be able to say anything meaningful about this, even in the negative, in the same way in which we wouldn’t be able to say anything meaningful about “mcfluffly mcglumpglumps”. This kind of thing is ‘not even wrong’.

(3) But we do want to say something about “red exists” - there is a point we want to make about it, and that point is that “red exists” ‘means’ that ‘red has meaning’ (and conversely, ‘red doesn’t exist' ‘means’ that ‘red has no meaning’).

(4) But we can’t say this because we just said that ‘red exists’ doesn’t have a meaning! So ‘red exists’ can’t mean ‘red has meaning’.

(5) So all we can say is that if ‘red exists’ did mean something, it would mean that ‘red has meaning’ (But of course “red exists" doesn’t mean anything!).

(5.1) So we can’t say that red exists 'means' red has meaning. This ‘contradicts itself’. [It can't both have a meaning, and not mean anything].

(6) So the “only contradiction” lies in the attempt to claim that the statement “red exists” ‘really means’ “red has meaning” [because the whole premise is that “red exists” has no meaning!].

—

Therefore! Forget the either/or choice between either ‘red exists is about red itself’ or ‘red exists’ is about the meaning of the use of the word red’. We can simply say, in all innocence, that ‘red exists’, and all this is to say is that something is red - and this ‘something’ need not commit us ontologically to anything in particular - it doesn’t have to be a ‘physical object’.

I'm much more comfortable with this reading than with my previous one. Could have got here earlier had I read the thread more closely. This is close to @Metaphysician Undercover's reading, but deviates from the conclusion MU draws: Witty doesn't opt for 'red exists = red has meaning' - the whole point is to show the error in this approach.

---

[Wrote this before I wrote the above:] Also, I completely missed the conversation about §58 on the previous pages though I was looking out for one. @Luke's point, about how the existence or not of red is analogous to the Paris rule being neither a meter nor not a meter long, is one I wanted to make as well, but left out in order to emphasize other things. Glad someone made it explicit:

[§58 is] analogous to the standard metre example, it is a means of representation rather than something that is represented, and so it yields no sense to say either that red exists or red does not exist. — Luke -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§60

§60 is long, but its quite a bit of fun. The basic question is this: is it the same to say that ‘the broom is in the corner’ as it is to say that ‘the stick of the broom and the brush of the broom are in the corner’? Witty’s answer is kinda like this:

Before veering more like this:

I like to think that this 2nd gif captures the PI's general orientation to metaphysics as a whole.

Jokes aside though, I would say that the question of motivation, of 'the point' of making such a distinction (and identification), becomes the central theme of the next few sections. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§59

§59 replaces the ‘elements’ of §48 with ‘constituent parts’: this vocabulary has the advantage of being a lot less metaphysically loaded than ‘elements’ which tend to carry with them connotations of ultimate-bits-beyond-which-one-can’t-go. ‘Constituent parts’ by contrast are a lot more ambiguous insofar they are relational: a constituent part of something is only a 'part' in relation to the thing it is a constituent of: thing being the case even if it is a ‘simple constituent part’, like the chair leg which is not said to be ‘composed of different pieces of wood’, unlike the chair back.

—

@“fdrake”: appreciate the appreciation :D -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§58

§58 is a dialectical nightmare. Here’s what I think is going on in it. It seems to me that there’s a kind of thesis-antithesis-synthesis structure going on here, where the thesis and antithesis are, respectively,

[Thesis]: the idea that “red exists” is a statement about Red qua Thing; and

[Antithesis]: the idea that “red exists” is a statement about Red qua meaning. Hence the ‘opposition’:

(eg. 1) §58: "If “X exists” amounts to no more than “X” has a meaning a then it is not [Thesis:] a sentence which treats of X, but [Antithesis]: a sentence about our use of language, that is, about the use of the word “X”."

(eg. 2) §58: "[Thesis]: It looks to us as if we were saying something about the nature of red in saying that the words “Red exists” do not make sense … [Antithesis]: But what we really want is simply to take “Red exists” as the statement: the word “red” has a meaning.”

Having posed these two ‘opposing’ takes, Witty then runs through some resulting ‘contradictions’, both of which follow from ‘taking the side’ of the Antithesis [‘red exists’ = meaning of red], against the Thesis [‘red exists’ = red Thing]:

§58: [Contradiction 1]: "the expression actually contradicts itself in the attempt to say that just because red exists ‘in and of itself’”.

§58: [Contradiction 2]: "Whereas the only contradiction lies in something like this: the sentence looks as if it were about the colour, while it is supposed to be saying something about the use of the word “red”."

The end of the section - what might be called synthesis, or maybe even better, dismissal - rubbishes the whole enterprise above, by simply acknowledging that "In reality … we quite readily say that a particular colour exists, and that is as much as to say that something exists that has that colour.”

The open question then is what this whole dialectical movement between thing, meaning, and then dismissal/synthesis is meant to show. I think that the point is to show that there is no ‘opposition’ between existence and meaning, and that insisting on the one does not preclude the other: it is both perfectly possible to say that ‘red exists’ - we do it all the time, ‘in reality’ - and that in doing so, we can still talk about our use of the word.

The last puzzle (for me) I want to address is the lemma that closes the discussion, the qualification: "particularly where ‘what has the colour’ is not a physical object.” - I think the idea is that 'existence’ here is not at all tied to ‘physical objects’ - we may well speak of ‘fictional objects’ and still employ the expression ‘red exists’ - this again being related to the ‘non-opposition' between existence and meaning’, and the attempt to ‘de-metaphysicalize’ the notion of existence.

—

Sorry this is a long one - disproportionate to the length of the section - but its a really tough one so I’ve had to try and dig at it. Still not totally happy with the exegesis and I think I’ve missed some details (particularly with respect to the ‘contradictions’ - I still don’t quite get how they are derived), but I think I got the general structure and motivation right, hopefully. -

Naming and Necessity, reading group?"A country bordering Greece" literally begins with an indefinite article.

:incredulous stare:

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum