Comments

-

Climate change and abortionbut often the answer we want colors how we see things - causes blind spots — Rank Amateur

That is one of several achilles heels we have. "Seeing is believing" also works the other way: "believing is seeing". What we believe, wish, want, fear, dread, etc. can (at times) determine what we actually "see". It isn't a flaw; it's a feature. If we are on top of things, we can be aware that our wishes are guiding our perception, but it's hard work to be on top of everything all the time. -

Could Life be a Conspiracy?I would not be surprised if solipsism was true and I was at the centre — Andrew4Handel

In a way, I think everyone can feel that way at times. Nothing is as real as your own experiences, and other people's experiences are only presumed to exist. Other people's behavior often does not make sense -- certainly not to me (or the "you" who did the OP) and maybe not to themselves. If some people's behavior makes sense to them, then they must be crazy.

There are times when I am around other people when I feel totally irrelevant. It's like I had become as insubstantial as ghosts are reputed to be. Is it them or is it me? Hard to say. Maybe I am real and the other people are insubstantial ghosts.

One's fluctuating ego (you aren't the only one whose Ego Indicator sometimes registers a zero--non-entity--and later can register a whopping 10.) I feel that way either when other people act as if I don't exist, or I act as if I didn't exist and they, of course, can't see me then. Yeah, it's crazy. That's our problem of being smart apes. I'm pretty sure other animals don't have these sorts of problems. A cat never has existential doubt. Neither do orangutans. -

Climate change and abortionThe biology on abortion is clear. A fetus is 100% human, and 100% alive. — Rank Amateur

Yes, of course. So is your liver 100% human and 100% alive. What else would a fetus be, but human and alive?

Personhood and rights therefore accorded are an argument outside science. — Rank Amateur

Yes, and that doesn't make it less important. And whether a fetus is viable or not lies in the field of science. A 5 month fetus is not viable, even with great neonatal intensive care. At 24 weeks it is viable with very poor prospects. 28 or 32 weeks, much better odds for a healthy start on life. 9 months -- best.

I do not consider abortion a procedure of moral indifference -- like having a bone spur removed. It is clearly a decision freighted with meaning for the individuals involved. It's a "might have been" that can never be answered. That's true about just about any decision. I want people to be able to make the decision to bear or not bear a child to be made on the merits of the parents' case, not on religious doctrine that once fertilized an egg is a person.

Many people make a horrendous mess of their children's lives. If you aren't able to be a good parent, then forego the experience, or wait until you are able. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate ChangeActually, if you do some research, the prevalence of cancer and other fears about radiation are unfounded by science. — Posty McPostface

Yes.

The rate of genetic defects among the animals that live in the forest around Chernobyl are apparently quite low. There are some genetic defects -- for instance, a bird species there that now tends to have a crossed beak (it doesn't align properly). The wolves, top predators, seem to be doing OK. One thing that was noted is that not very many animals live in the zone underneath the new thick forest litter and above the uncontaminated soil. How rodents living in the contaminated soil zone are faring, don't know. Of course by now some of the contaminants have decayed considerably.) A number of species are apparently living shorter lives.

Bear in mind, that humans were evacuated fairly quickly. Not quickly enough, probably, but their exposure was limited by the evacuations. Also, thyroid cancer can be prevented by administering potassium iodide after exposure. The non-radioactive PI saturates the thyroid, preventing the uptake of radioactive iodine.

Seems to me the death rate among workers trying to contain the mess (in the hours and days after the explosion) didn't fare too well.

The other thing to remember is that the Soviets had reason to downplay the disaster's health effects and post-collapse Russia was a largely disorganized mess. How well cases have been followed, I don't know. -

Very Sunny Uplands!I beg to differ. The window is closed as a consequence of the nature of humankind. — karl stone

I beg to differ that the window is closed as a consequence of humankind's nature. The window is closed because some human beings have decided that their short-term gain is worth more than our long-term survival.

The humans who control power and policy are focused. The rest of us are a diffuse mass, pointing in every direction. As it says in Bernstein's Mass: Half of the people are drowning, and the other half are swimming in the wrong direction. Half the people are stoned, and the other half are waiting for the next election. (Not far away now on this side of the pond, Karl. How about the desperate last minute vote to stick with Europe after all?)

I find it difficult to imagine how one could think that their short term profits are worth humankind's survival, but that seems to be where the rich and powerful are at. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate Changethe social stigma of radiation — Posty McPostface

Ask the people who lived in Chernobyl and Pripyat about "social stigma".

The trouble with fusion is that getting it to work on a controlled basis has proved to be damned difficult -- more difficult than we have so far been able to overcome. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate ChangeHighly trained in tree related disciplines, and puns — All sight

Posty wants to be one with the forest, but he is barking up the wrong tree. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate ChangeI use the word embrace, in a stipulative manner. — Posty McPostface

Everybody likes a hug, so I don't have a problem with embrace. Maybe we should have sex with climate change. You could say "Acknowledge" instead of embrace, or "take climate change into their consideration". -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Climate ChangeThe world is currently producing about 18 terawatts of power. Solar had better get busy.

1 Terawatt Hour: Electrical energy consumption rate equivalent to a trillion watts consumed in one hour. -

The problems that philosophy faces.Is "angst" a problem that philosophy faces and has to remedy?

Is philosophical pessimism also a 'problem' that philosophy must deal with? — Posty McPostface

No more than happiness, contentment, and optimism. Everything is pfodder for philosophy.

What can philosophy do about these attitudes? — Posty McPostface

Encourage people who have those attitudes to deal with it, if it is a problem for them.

I suppose philosophy could tell people who express unhappiness at great length to just shut up about it, we are tired of hearing all the bellyaching about how bad the world is, and want to get back to the burning issue of bipolarity in Witts'is'face. -

How to Save the World!More may not be better but bigger is definitely superior, up to the point where one starts tripping over it.

-

How to Save the World!Darwin published Origin of Species in 1859 - a volume not received at all kindly by the religious.

What about Helmholtz, Christian Doppler, Paul Ehrlich (the one born in 1853), Richard Owen, Hinrich Rink (Danish geologist), Max Saenger (had the bright idea of stitching up the uterus after a caesarian), Bell, Pasteur, Lister, Koch, Mendel, Mendeleev, etc.???

Were there riots over them? — karl stone -

How to Save the World!If however, you're saying that religious thinking was no obstacle to scientific thinking, then I disagree entirely — karl stone

Well, of course I'm not saying that religious thinking was no barrier. It was and it still is a barrier, whenever people take faith as fact, doctrine as law, and parochial practice as universally normative. The saving grace was (mostly was, but still somewhat is) that sophisticated thinkers who so wished could entertain heretical scientific ideas and religious ideas at the same time. I'll cite a fundamentalist sister as evidence: She ardently believes all sorts of conservative Baptist 'stuff', like the 6 day creation, but at the same time is quite sophisticated about medical practices. She doesn't expect God to take care of her brakes or oil. She's always on top of that sort of stuff.

Giro Fracastoro — Bitter Crank

Fracastoro died an honored man. He wasn't censored, probably because his theory didn't challenge the dominant paradigm of creation. Subverting dominant paradigms can still make one unpopular, even in SCIENCE! ("He knows more than you do. He has a master's degree--in SCIENCE!" Opening lines of a National Public Radio science comedy routine, "Ask Dr. Science".)

Oops, we've crossed the pond — karl stone

Doesn't matter, because photography and telegraphy also played a role in the Crimean war. So, you can rest in peace on your side of the pond. Lincoln, of course, wasn't managing the British or Russian forces. He was still practicing law in Illinois. -

Arabs and murderno-one gave a shit about that — Baden

Whether one expresses a high give-a-shit rating or not depends on the opportunity--a place and a time. Khashoggi is getting "official outrage" so that creates a bigger space for others to express their feelings. I'm pretty sure that firing on a bus of people (children, men, women, whoever) appalled a lot of people. The children were, for sure, not shooting at anybody. The whole Yemeni thing strikes me as appalling (but I don't know much about it). I don't know why there wasn't more "official outrage" about the children on the bus. -

Arabs and murderThat Jamal Khashoggi was a "guest" in the Arab embassy makes little difference to me. What is appalling is the Saudi's willingness to silence a critic with murder and dismemberment. That the Saudi thugs arrived with knives and saws underscores the premeditation of murder. Murder to silence a critic; not a revolutionary or terrorist: a critic.

I have read reports that allowing Saudis to attend cinema or allowing women to drive cars is window-dressing. It's strategic window-dressing: just enough to make it appear that reform is happening. In actuality, the Saudi royal thuggery rigidly suppress any criticism of the regime. This isn't new.

Trump is worried that if we criticize the Saudi too severely, they will take their military purchases elsewhere. They probably would react that way. It isn't as if there aren't any other military manufacturers at the world arms bazaar. Personally, I think we're far to involved in the world arms trade as it is. And if Trump is worried about arms sales, I'm sure Iran could have taken up some of the slack if the Grand Asshole of Washington hadn't scuttled the nuclear weapons deal with Iran. -

Climate change and abortionInterested if others see this paradox — Rank Amateur

I do not see a paradox, and I don't see an obvious connection either. The cause of me not seeing what you find glaringly obvious likely has something to do with how I define "person": I don't consider a non-viable fetus to be a person. Potential, yes; actual, no. Very, very few viable near-term fetuses are aborted.

I also don't think of the just-conceived egg/sperm combo as a person, or an ensouled being. When does a fetus become a person? When the first-cry infant is held in the arms of his or her parents, personhood has been achieved.

Hundreds of thousands of species will take the brunt of climate change. Humans are but one of the many, though we have guilt on top of potential extinction. It is by our fault, by our most grievous fault. -

How to Save the World!The wealthiest 1 percent of American households own 40 percent of the country's wealth

It's even worse on a global scale.

Richest 1 percent bagged 82 percent of wealth created last year - poorest half of humanity got nothing

Published: 22 January 2018

Eighty two percent of the wealth generated last year went to the richest one percent of the global population, while the 3.7 billion people who make up the poorest half of the world saw no increase in their wealth, according to a new Oxfam report released today. The report is being launched as political and business elites gather for the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. -

How to Save the World!Had science been adopted by the Church from 1630 - and pursued, and integrated into philosophy, politics, economics and society on an ongoing basis... — karl stone

Your view that the Church (already ruptured by Luther, Henry VIII, Calvin, et al,) held so much intellectual sway over Europe in the 17th century that science was a subsection of theology is not sound, imho. The universities had been in business since the 12th century and had been chipping away at the intellectual citadel of the church. True enough, the French Revolution was still 160 years off; Russia, Spain, and various other princedoms didn't get enlightened for a long time. But a secular-scientific view of the world was none-the-less forming among intellectual elites.

Take Giro. Fracastoro (1476-1553) a physician in Padua. In 1546 he proposed his theory that disease, ("infections") were spread by "spores" or some such agent. He was right, but the necessary wherewithal to pursue this theory didn't exist in his lifetime, or until numerous lifetimes later. "Finding scientific reality" was hindered more by the difficulty of the search than interference by religious thinking.

If some bright mind made progress -- like John Hunter the anatomist and physician in the late 18th century -- there were not always bright minds on hand to follow up. The social structure of the scientific enterprise was barely developed. Pasteur, Lister, and Koch didn't have to overcome the church to demonstrate the role of bacteria in disease; they had to overcome conservative doctors who stuck with old theories of "miasmas" causing disease.

Still, the study of nature was producing results that could be turned into technology. Watt's steam engine worked, but it leaded steam badly, reducing its efficiency. It was another Englishman*** who had developed methods of drilling precise cylinders in cast iron that made Watt's engines work much better, leading to bigger and better...

Batteries, photography and telegraphy are further examples of science and technology in the early 19th century. The telegraph was introduced in 1840; by 1862 it had become critical to Lincoln's management of the American Civil War.

By the mid 19th century, our understanding of the natural world was reaching a critical state where knowledge would take off.

In summary: It was the great difficulty of understanding the world without any prior scientific insight that made the task slow and difficult.

***Maybe John Wilkinson, who developed methods of boring precise cylinders in cast iron -

The US national debt: where is it headed?Hey, in the 1960s the rate on big wealth was 91%. What do you mean, the government can't effectively tax wealth?

-

How to Save the World!Marx saved capitalism. — karl stone

Really? Marx was describing the historical processes he saw at work. He didn't save capitalism -- it didn't need saving. Marx predicted, he didn't prescribe. He may have been on the side of the workers. but the workers have tasks that they have to fulfill, from Marx's perspective, and if they didn't fulfill those tasks, then...

He didn't tell anyone to begin the revolution in 1917. Marx--as far as I can tell--predicted the revolution would happen when the working class was fully developed and capable of taking over capitalism. Have we reached that point yet? Maybe -- workers at all levels of the corporate structure have the skills to operate the corporation. In fact, for the most part workers (low level to high level workers) do operate the corporation.

What workers lack is "class-self-consciousness": the kind of consciousness that illuminates their class interests and informs their actions. Most workers in the US, at least, think of themselves as temporarily embarrassed tycoons of some sort. Silly them! Their problem is that they lack class-consciousness, and heaven and earth have been moved to make sure they don't develop class consciousness.

That's not Marx's fault. In the long run, if the working class doesn't fulfill it's destiny (as Marx sees it), then one of the contending classes -- workers or capitalists -- will be destroyed. That is not a desirable conclusion to class conflict. -

How to Save the World!We just can't help ourselves. — Pattern-chaser

In so many ways this is true. It's true because we are, after all, only very bright primates. We have drives which push our behavior in ways that our higher thought capacities can see are ill advised, but the drives remain in place -- they are deeply woven into our beings. Our drives were tolerable when there were fewer of us -- maybe 7 billion fewer. When we were a few hunter gatherers we could not get into too much trouble.

Then we settled down; we developed agriculture, built cities, organized governments, harnessed the energies of slaves and beasts to produce large surpluses of wealth (which accumulated in few hands), and began our more recent history. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott takes the view that a human urge to control led to the early states, and their exploitation of the people under their control. Scott has a deep libertarian streak, I suspect. I haven't finished the book, but I think he is going to name the State the Serpent in the Garden of Eden.

I'm not at all convinced, but there is certainly unhappy business at the very beginning of our more recent (last 10,000 years) history. -

How to Save the World!I'm not an electrical engineer - I'm a philosopher. I've pointed out two dozen times that I'm only seeking to prove in principle that it's technologically possible. It's not fair to expect schematics and a business plan. I'm one man trying to correct a 400 year old philosophical error in the political history of my species, as a means of absolving science of the heresy of which it was accused, that in turn made it a whore to capitalism and a lobbyist on the steps of Congress - when it rightfully owns the highest authority, and should command at least some share of the enormous wealth and resources it has made available. — karl stone

Hey, I'm not an electrical engineer either -- nor do I know anything about finance. (I was an English major.) I think you've brought in quite a few technically possible schemes. Making hydrogen with solar power plants floating on the ocean is technically possible. But I don't think that connects with your mission of absolving science of heresy. If capitalism makes a whore of science, that's not the fault of science; capitalism prostitutes everything.

Granting science the highest authority is debatable because science doesn't produce truth about everything. It has the capacity to give us a truthful report on the physical, natural world. That's no small thing. It is gradually revealing how our brains work--that is most excellent. I trust science.

What science is not equipped to do is tell us what we should do. Science could help launch the industrial revolution by revealing how things work. It could not inform the first industrialists whether they should build steam engines, power looms, and railroads. Science revealed the nature of electricity; it could not reveal whether the telegraph, telephone, and light bulb were good ideas.

What we should do is the province of philosophers.

I don't think science is much encumbered by charges of heresy. What encumbers us all is the grip of capitalist economics and ideology on most of the world. The operation of capitalism is observable and predictable; that's what Karl Marx did. Capitalism is apparently blind to the consequences of its own operation (or at least has major vision problems). Capitalists who are willing to prostitute science probably aren't willing to consult science for advice.

Therein lies a major part of our present problem. -

Show Me Your Funny!Merciful Greece: fat tourists on the island of Santorini will no longer be able to ride donkeys up the mountainside. They will have to walk. Too many donkeys have been injured carting lard asses around.

This is not a joke, but I found it quite amusing, even though I myself would have to forgo a ride on a jackass. Fat people may not be able to lose weight, but they can be more fit. So mach schnell, swine!

I once contemplated riding a mule down the path to the bottom of the Grand Canyon. I was much slimmer then. When I got there I was horrified to discover just how horrifying even standing on the path was; it gave me a panic attack, with that vast empty volume of space, let alone sitting five feet up on the back of a mule walking right along the edge, the way they do.

Plus, the mules were very arrogant about their confident sure-footedness. -

The US national debt: where is it headed?It is becoming clearer, but I am not becoming happier about it.

-

The US national debt: where is it headed?

From Marketplace (NPR) But for now, interest rates are still low. The markets continue to gobble up our debt. The U.S. dollar is the world reserve currency. Is anybody out there saying the U.S. isn't a good bet fiscally?

David Primo: And that's sort of the benefit of being the United States and also the risk of being the United States. So the benefit, as you just said, is right now we have the ability as a country, because we are the world's reserve country, to perhaps take on more debt than other countries can. American debt by comparison is very, very safe. And as a result, there's still a lot of demand for our debt. Interest rates are low right now. But a lot of this debt that's being issued is short-term debt. What happens when that debt has to be reissued, and interest rates that other countries and individuals will demand to buy up that debt goes up all of a sudden? All right, the fiscal picture gets gloomier. And, you know, there isn't an announcement that's made, oh tomorrow, the rest of the world is going to stop buying up U.S. debt. It can happen very suddenly.

How can we know if there's a crisis coming?

David Primo: That's the risky part; what economists like to call a creeping risk. Today it's not going to affect us, tomorrow it's not going to affect us, but it builds up over time and eventually you end up in a crisis situation. If our national debt doubles again, as it's predicted to do as a share of the economy in the next 30 years, for the average American it's going to have an effect on the ability for the federal government to undertake the activities that Americans think are important. So there's a lot of talk about how Republicans want to, you know, eviscerate entitlements. -

How to Save the World!We already send electricity all over the place. Yes, there are some losses during transmission. Electricity made by Manitoba Hydro may end up turning motors in St. Louis Missouri, not just in Winnipeg.

The value of electricity makes almost any location cost effective. Put a solar farm on that corn field. The electricity will be worth far more than the corn. A wind turbine doesn't take up much space on the ground, maybe 400 square feet. There is nothing you can grow on 400 sq. ft. worth as much as the electricity produced from that one turbine-bearing mast. -

How to Save the World!Had man in a worshipful manner - made it his vocation and duty to know what's true, and do what's right in terms of what's true - — karl stone

Here is your problem:

You are assuming that "the truth" is crisply, concisely, and clearly stated in clean Helvetica text and that the upshot of seeing the truth is equally obvious. That's not the way truth usually appears. More likely than not it will be laboriously spelled out in obscure language and printed in some barely readable obscure font (figuratively speaking, you understand).

Then one has to figure out how to implement the truth that one has understood (correctly or not). -

The US national debt: where is it headed?I assume you realize that "printing" money is not the issue, it is the money supply - which mostly consists of figures in computers. — Relativist

For god's sake, don't be such a literalist. Of course I understand that only a certain kind of money (paper currency) is actually printed. -

The US national debt: where is it headed?If adding to the money supply is so harmless, then why don't we just pay the interest on the debt with freshly created money? Or is it the case that there are some limits to what fiat currency can accomplish in the world?

-

The Supreme Court's misinterpretations of the constitutionConstitutions are not "sacred" documents like the Ten Commandments--carved in stone and handed down from heaven and valid forever. They are working documents designed to address the perceived problems of establishing government at a given time. — Bitter Crank

at you have done is just what you argued against, which is to make the Constitution sacred in the sense that what it is said to say is the highest law of the land, untouchable by democratic effort. — Hanover

You don't have to respond, but I honestly don't see how you derived your conclusion from what you quoted. I would think that calling the constitution "working documents designed to address the perceived problems of establishing government at a given time" was not making the constitution sacred.

I think we were taught in school to hold the constitution as a sacred document. Many years since, I think the constitution is not sacred, not perfect, and too difficult to amend.

The liberal Warren Court was in place for a long time -- especially if one was a conservative. Now we will have a conservative court in place for a long time (so it will seem to liberals). If we are going to change justices more often, (like give them one ten year term) then the scope of their jurisdiction needs to be much more limited. -

The US national debt: where is it headed?2. The US is a model of a democratic state with a massive chronic trade deficit which has reached the point of being unable to adequately fund its government and military, but it isn't able to raise taxes (or tribute). Instead, it just has a debt which would take out the global economy were it to default. — frank

The United States IS able to raise taxes. The fact is the politicos in Washington don't want to raise taxes. It wasn't that long ago that the wealthy high earners (the top 5%) paid much more in taxes. In 1965 the tax rate on the wealthiest individuals was 91%. The current level of taxation on high incomes was recently lowered from 39% to 37%. 91% is what it takes to actually balance the budget and pay off old debts.

During the Vietnam war there was much discussion of "guns vs. butter" -- the cost of war vs. the costs of domestic programs. Johnson didn't want to choose either one, he wanted both. As a result a significant amount of debt was piled on just as old debt was being retired. During Reagan's administration (1980-88) tax cuts were combined by the ruinously expensive and pointless arms race called 'star wars'. More debt. Clinton was able to balance the federal government some years; I may be mistaken, but his budgets may have been the last ones.

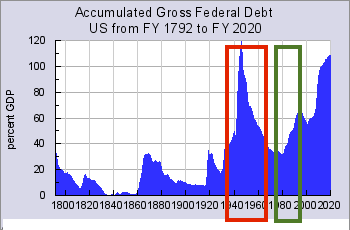

red rectangle: WWII; green rectangle: star wars and tax cut

-

The US national debt: where is it headed?It ignores how governments actually go about attaining and using its mone — MindForged

National debt, in a country with a fiat currency, that has lender confidence, has absolutely nothing at all I in common with personal, or local government debt. — Rank Amateur

I understand that personal or corporate debt isn't the same as national debt. However, the fact is that national debt is a recurrent item of discussion among economists and politicians, both.

I have difficulty believing that there are no consequences to an steadily growing nation debt. fiat currency or not. After all, we have paid off the debts from past wars: $4 trillion from WWII, for instance was paid off sometime by the late 1960s. (The cost of WWII was $350 billion in 1945 dollars. That was something like twice government spending since 1776. A lot, in other words.) Other countries seem worried about their own and others' debts.

Printing money generally has the effect of devaluing a currency. If last year there was $1.5 trillion in circulating currency, and another 1.5 trillion dollars worth of money is printed, then a dollar can't continue to have the same purchasing power.

Granted, fiat currency doesn't have any inherent value, but obviously a country can not become fabulously rich by magically creating huge amounts of money. If that were so, then every country would be printing their way to financial heaven.

So, explain how debt is not a problem. -

The US national debt: where is it headed?Here is the 2015 US budget chart (from the Science web site)

According to this chart, 6% of the budget is being spent on debt. 6% on debt may not seem all that large, but it isn't discretionary spending. It's part of the very large non-discretionary spending on social security, medicare, medicaid, and non discretionary defense spending. Without more taxation (and there are rich people to tax) spending on good discretionary projects like science, education, the environment, R&D, transportation, Centers for Disease Control, and so on will have to be cut.

The solution is to increase taxation (long since reduced) on the richest portion of Americans who have more wealth than the rest of the population. I have looked deep into my heart and I find that I can stand their unwilling sacrifice of ... let's say, hmmm, $50 trillion. You can rest, assured that after being so fleeced, they will still be able to enjoy fine wines, excellent meals, haute couture, and so on. They might have to put up with a slightly smaller yacht, a less pretentious collection of houses, and so on. They would not be reduced to eating beans and wieners (unless, of course, they preferred beans and wieners).

But then again, if we can get $50 trillion dollars out of the super rich, we might as well take the rest of it too, and let them be grateful to make soup out of wiener water. -

The US national debt: where is it headed?There seem to be dramatic different ways of interpreting the significance of national debt, varying from crisis to indifference. Some kinds of debt make sense: a mortgage at reasonable interest rates makes sense. At unreasonable interest, no. Steadily accumulating credit card debt doesn't make sense: one should restrict one's spending to one's income, with only small amounts of short-term debt being tolerated.

National debt seems more like credit card debt to me. Some of it may be as necessary as a mortgage, but a lot of it is living beyond one's income. Now, the US Government could, if politicians were willing, increase its income through taxation, and could put a ceiling on its debt or lower its indebtedness. It would be a good thing, because the interest on the national debt is huge, and costs us the opportunity to accomplish worthwhile goals.

Here is a chart from the Australian Government on world debt: I don't find much solace in it.

General government net debt 2010

-

How to Save the World!He's famous for pointing out the discrepency between the geometric rate of population growth 2,4,8,16 etc, against the arithmetic rate 1, 2, 3, 4, etc, at which agricultural land could be increased — karl stone

Yes, I know who Malthus was, and that his predictions did not pan out. However, I didn't reference Malthus, and neither did Kunstler. Our situation today isn't a Malthusian problem. Old Thomas has become a stumbling block which we trip over. People in general fall somewhere on the spectrum of optimism and pessimism. Whether their location makes sense or not doesn't seem to have any influence on their thinking.

As I indicated above, I'm favorably disposed towards techno-fixes when, and if, they are appropriate, and when and if they have a good chance of achieving the desired ends. The problem we face with global warming isn't malthusian. Had Malthus had the insight to see that the industrial revolution going on around him would eventually lead to serious problems, he would rank up there with Newton. Someone (I forget, don't know where the reference is) may have detected signs of climate change roughly a century ago, but their observation was isolated, and could not be fit into a pattern at that time.

The problem is CO2, methane, and some other heat trapping gases. They are in the atmosphere now, and won't disappear tomorrow. The solution lies in changing human behavior. Unfortunately, achieving major shifts in human behavior and thinking is much more difficult than turning an air craft carrier or the largest oil tankers around on a dime.

Were we able to change our thinking, our cultures, our behaviors on a dime; make industrial policy based on subtle shifts in the climate 50 years ago; shift to public transit away from private autos and air travel; live much more simply; become vegetarians; and so on and so forth, we could have prevented or solved the problem decades before it became critical, we'd be in good shape now. Alas...

The best we can do at this point is mediate the coming disaster as much as we are able (however much or little that turns out to be). Que será, será. -

SocialismMore to argue against abolishing private ownership — Marchesk

@Tinman1917 There are two kinds of property: personal property (your books, soup bowl, spoon, cell phone, four-poster bed with a large mirror mounted on the ceiling, and the peasant hovel in which all of this is located. The other kind of property is "capital" property: factories, apartment buildings, railroads, warehouses, farm land, ships, and the like. Capital property produces income for the owner by receiving rent from the apartment buildings, profits from the railroad operations, and so on.

My understanding is that personal property (within reason) would remain personal property. If your residence was a 100 room mansion, that probably would count as a pile of plunder and you would not be staying there (except as a resident of one of the locked attic rooms).

Capital property, on the other hand, would not remain in the hands of the owners. The workers would take it away from the owners, and it would become the property of The People.

The occupants of the former factory/railroad/Bloomingdales store, warehouse, hog farm... would take on the role of stewards of the former business property, to maintain the assets (machinery, buildings, raw materials, etc.) and to carry on production if the democratically elected People's Congress on Production decided that they wanted whatever it was that the factory made.

The people might decide that the light rail vehicle factory would continue in business while the stretch limo plant would be converted to making bicycles.

Is this socialism or communism? I don't much care what it is called. Socialism is fine by me. Screw the dictatorship of anybody. -

Is this even possible?Very tall trees, sequoia or redwood, manage to lift a lot of water from their roots into their canopy. You might investigate how they do that. (It's capillary action, of course. Could one duplicate the area of a sequoia's surface, under its bark, devoted to upward bound capillary action?

A piece of information from Wikipedia

"The water pressure decreases as it rises up the tree. This is because the capillary action is fighting the weight of the water. ... Scientists have found that the pressure inside the xylem decreases with the height of the tree, and similarly, the size of the redwood leaves decreases with the decrease in pressure. May 6, 2004" -

How to Save the World!@karl stone Did I recommend this author, this book to you?

Too Much Magic: Wishful Thinking, Technology, and the Fate of the Nation by James Howard Kunstler

Kunstler details the nature of the environmental crises. While doing that he also punctures many a delusion about what is possible. For instance: "We'll build huge numbers of windmills and square miles of solar panels." Great idea. But... given that we are past peak oil, what will happen when our million windmills and millions of solar panels wear out? We still have relatively cheap petrochemicals with which to carry out this production. Forty years from now? Sixty? Much less oil available and much more expensive. I am thoroughly enthusiastic about windmills and solar, but a lot of energy is needed to build the steel masts from which the windmills are hung. I assume a fair amount of energy is required to build solar panels too and that they probably don't continue to work forever.

Kunstler's point is that there are no magical solutions to our several interlocked environmental crises. -

How to Save the World!The system I describe has all the thermodynamic efficiency of a steam train — karl stone

Indeed, but if we could build large solar plants in the ocean at the equator, why wouldn't we just run a wire from the complex and plug it into the electrical distribution systems of India, China, SE Asia, Africa, or South America?

BC

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum