Comments

-

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?Sure, but Popper is both a philosopher of science and a political philosopher, and would not usually be considered an analytic philosopher since his main concern was not with language, semantics and logic. — Janus

Correct me if I'm wrong, but my understanding is that Popper is socio-historically located within the stream of analytic philosophers. I know this has been a topic of contention in this thread, but as I understand the term "analytic philosophy", it is not the philosophy narrowly concerned with language, semantics, and logic as topics, but the philosophy that approaches any of its topics, including things like political philosophy, in the manner pioneered by the Vienna Circle et al, with logical rigor, breaking things down into pieces analytically, hence the name.

Also, I think you meant 'epistemology' not "etymology". — Janus

Correct, I must've clicked the wrong autocomplete button on my phone. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?Grand systems, by their very nature, are wrong; and I mean both in terms of truth and morality. — Banno

Explain? -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?I think part of the reason [we don't really see system-builders anymore] is just because there's so much knowledge out there that I just don't see how anyone can put forth something like that today — BitconnectCarlos

Someone else mentioned up thread, in a way better than I can recount from memory, how one of the founding principles of analytic philosophy was the rejection of system-building, so I don't just think that it's hard to do, I think it's being actively avoided, for reasons I still don't really comprehend. The lack of systematization, or architectonics as @apokrisis would say, is the thing that I found most lacking in my own (analytic) philosophical education, and the thing that spurred me to start my project.

Interesting, could you explain please? Maybe cite an example? — BitconnectCarlos

I did, right after the bit you quoted in that post:

my political principles are grounded in my normative ethical principles, which in turn depend on my meta-ethical framework, including moral semantics, which invokes philosophy of language concepts such as speech-acts — Pfhorrest

So politically, I'm a socialist because I'm a libertarian, and I'm a libertarian because of my deontological normative ethics (something like the non-aggression principle that you're probably familiar with), and my deontological ethics hinges on there being things that are objectively right or wrong (if it's not actually wrong to aggress upon people, but just "unpopular" or "illegal" or something, then the whole politics falls apart), and that account of things being objectively right or wrong can't be explained without explaining what "right" and "wrong" (etc) even mean, which is an account of moral semantics, which of mine hinges on the concept of speech-acts, but in any case all moral semantics, being semantics, hinge on some linguistic concepts or other. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?Whatever Analytic Philosophy is it is not concerned with politics and never pretended to be. — Janus

Popper sure seemed concerned with the political implications of his philosophy of science and epistemology. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?I think the thing that makes analytic philosophy as such as socially ineffectual as it is, is precisely its aversion to system-building. While piecemeal investigating particular problems can be productive in those areas, I think it’s also very important to keep the big picture in mind.

For example, I can easily see myself in a political argument ending up talking about speech-acts and other philosophy of language stuff. See, my political principles are grounded in my normative ethical principles, which in turn depend on my meta-ethical framework, including moral semantics, which invokes philosophy of language concepts such as speech-acts. The normative ethics itself also depends a lot on deontic logic and so logic and language generally, and the pragmatics of my politics hinges a lot on linguistic pragmatics and related rhetorical theory.

It’s all connected, so it all has to be able to fit together, every view on every topic has implications on the possibilities in many other topics. That big picture, and the practical application that it enables, is what analytic philosophy seems to miss the most. It makes some great tools, it just need to actually put them to the job too. -

Mathematicism as an alternative to both platonism and nominalismIf correspondence to physical law is an argument for mathematical realism, what to make of the rest of mathematics? What of the infinity of laws we could write down but have no apparent reality? — Kenosha Kid

In this view that I'm laying out in this thread, our concrete universe is just one of the infinitely many abstract mathematical structures. (We don't know for sure which; that's what physics is to investigate, which is all I have to say in response to the bulk of your post.) All of those other mathematical structures that are not this one, nor parts of this one, still "exist" abstractly on this account, but not concretely, since "exists concretely" just means "is part of the same abstract structure that we are a part of", on this account.

Maybe for illustration, imagine a nested set of simulated universes, each full of simulated people who built the next simulation down. The deepest simulation seems to be a physical world to the people in it, but is actually an informational structure embedded in what seems to be physical stuff to the people in the next level out, which in turn is actually an informational structure embedded in what seems to be physical stuff to the the people in the next level out, and so on, until we get to actual physical reality. Why cannot we just treat actual physical reality as merely the deepest of those informational structures -- and so an abstract object -- one merely not embedded in anything else? And once we've granted the existence of that one abstract object, and subsumed all concrete objects within it, why not equally grant the existence of other abstract objects of which we are not parts? -

The Bias of Buying.Pfhorrest I think you have some skin in the game here. Would you view something like the field of linguistics, mathematics or ethics as something that was created, or discovered, by philosophy? — MSC

I think the historical way to think about it is that philosophy divided, like a cell undergoing mitosis, rather than a human giving live birth. These other fields used to be considered part of philosophy, as almost everything did, until they developed enough to split off and become their own things. What we call philosophy today is what’s left after all those other fields split off, and their subjects still overlap at the fringes, but there are things within each offshoot that are clearly not philosophical now, and things within philosophy that clearly have nothing to do with that offshoot (but maybe have much to do with another).

You might think of philosophy as like a stem cell, as yet undifferentiated into any more specialized cell, while those other cells that split off from it have all become more specialized. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?My way of confronting this is to try and convince philosophers to enter into politics, not just political philosophy I mean seriously try to get into politics. — MSC

While that is a lovely idea, I think it would take a very rare personality to both do philosophy well and also survive a political race. Most people with aptitude in one arena seem to lack it in the other. -

Mathematicist GenesisThis is a very ambitious thread. — jgill

Mostly because fdrake majorly upped the ante on the level of rigor I expected. I had hoped for a dozen or two posts about the size (and level of detail) of my OP, but instead he started giving us so much more. -

Where could I find a quietist philosopher or resource to defuse philosophical problems with quietismThat seems like a strange way of putting it. I would agree that the definition of “common sense” is something like “something that has a broad consensus”, in the sense of being largely uncontroversial. But the specific philosophical principles that I think rightly enjoy that broad uncontroversial consensus do not include anything like “whatever enjoys a consensus is probably right”, if that’s what you mean. That would actually violate the second example of a common-sense view that I gave, that somebody (in this case a majority) just saying so doesn’t make it true.

-

Where could I find a quietist philosopher or resource to defuse philosophical problems with quietismI defined that right in the post you quoted: "the kind of view that I expect people who have given no thought at all to philosophical questions to find trivial and obvious".

Specifically, I go on to say that such "common sense" consists in things like that there is more to truth than just belief, that someone just saying so doesn't make something true, that we are justified in tentatively believing things that seem true even if we can't completely prove them from the ground up yet, and that we can turn to the experiences we have in common with each other to figure out what's more or less likely to be true. You know, the way ordinary people operate in their ordinary lives every day. -

Who was right on certainty...Descartes or Lichtenburg?This is just quibbling over phrasing now. When I speak of “experience” I mean something like Descartes probably means by “awareness”, including sensory, but also awareness of the goings-on in our own minds.

-

Daemonic SignI would recommend the book Origins of the Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes for understanding Socrates experiences of voices. — Jack Cummins

I was about to say the same thing! -

Who was right on certainty...Descartes or Lichtenburg?Even if it were insisted that experiencing of thought follows necessarily from the rational activity of thinking, we should see cognizance from perception, which is experience, and cognizance from thought, which is reason, accord with separate and distinct rational faculties, having no logical warrant for being considered congruent consequences. — Mww

In the way Descartes uses “thought”, it is entirely possible that all perceptions are merely thoughts: we could just be imagining, dreaming, hallucinating, all the things that we “perceive“.

In a way similar to rebuttals of solipsism, I say that in that case there is no practical difference between the “imagined” world and a “real” world: there are still parts of that whatever-is-being-experienced that are beyond our control or our knowledge, just like a “real” world “would be”, so we need to treat that object of experience the same way we would treat a “real” world... which is to say, treat it as real. The real world just is whatever this stuff I’m experiencing is.

Some of that stuff might be parts of myself (not just my body, but the insides of my mind too), sure, but that’s fine, that just means I myself am part of the world, no surprise there. -

The meaning of the existential quantifierI think you’re on the right track there, and my own thoughts on that same track show up in my names for my proposed versions of “existential” quantification and disjunction: for-some(x,F(x)) and some-of(a,b,c,...).

(Where “some-of(a,b,c,...)” just means “a or b or c or ...”).

I actually construct “for-some()” explicitly from a more general “for()” function with an embedded “some-of()” function; and I similarly construct “for-all()” out of that same “for()” function with an embedded “all-of()”, which in turn is my version of conjunction.

(Where “all-of(a,b,c,...)” just means “a and b and c and ...”). -

Who was right on certainty...Descartes or Lichtenburg?Yeah, we cannot rule out that the experiencer is the same thing as the experienced: it could be one thing experiencing itself.

-

Where could I find a quietist philosopher or resource to defuse philosophical problems with quietismI'm reminded of something I wrote in the intro to my own philosophy book:

"The general worldview I am going to lay out is one that seems to be a naively uncontroversial, common-sense kind of view, i.e. the kind of view that I expect people who have given no thought at all to philosophical questions to find trivial and obvious. Nevertheless I expect most readers, of most points of view, to largely disagree with the consequent details of it, until I explain why they are entailed by that common-sense view. Many various other philosophical schools of thought deviate from that common-sense view in different ways, and their adherents think that they have surpassed that naive common sense and attained a deeper understanding. In these essays I aim to shore up and refine that common-sense view into a more rigorous form that can better withstand the temptation of such deviation, and to show the common error underlying all of those different deviations from this common-sense view."

I guess as much as I dislike Wittgenstein's attitude, we have more in common than I often think. -

A plea to the moderators of this siteLots of people read these threads, some of them very likely, impressionable young people, are you claiming that a person is doing something wrong by criticizing religious error? You — JerseyFlight

I'm not saying that anyone is doing anything wrong by criticizing religious errors. I'm saying that, for the most part, it's not worth the effort of engaging; they won't be convinced to change their minds, so you'll just be wasting your own precious time arguing against a brick wall.

If some people do want to spend the time to give a quick rebuttal for the sake of onlookers, then that is valuable, for the onlookers' sake, sure.

You are here calling it "shallow," "little-reasoning," and comparing it to the irrationality of religion. — JerseyFlight

I'm calling the religious threads that this thread complains about "shallow" and "little-reason", not this thread itself.

But I'm saying that threads like this complaining about the existence of shallow unreasoning religious people are little better. The mods will eventually delete low-quality or evangelical threads -- if they don't have any high-quality responses yet. (It takes them time, because they're not here watching the forum like a hawk 24/7; they're people with lives). So giving a quality rebuttal to them makes it less likely that they will be deleted. And posting threads like this complaining about them... just creates more filler that isn't quality philosophical discussion on the forum. -

Does Analytic Philosophy Have a Negative Social Value?This argument is dumb. Analytic and Continental philosophy both tackle important questions. There is a continuous spectrum from mathematical, ideal, or linguistic abstractions, to the experiential, embodied, practical life. (That's why I subtitled my book "from the meaning of words to the meaning of life").

Neglect either and the other suffers for its absence. This is true of Analytic philosophy for neglecting the experiential/embodies/practical side, but it's also true of Continental philosophy for neglecting the mathematical/ideal/linguistic side. Both have their value, and each is of greater value in combination with the other.

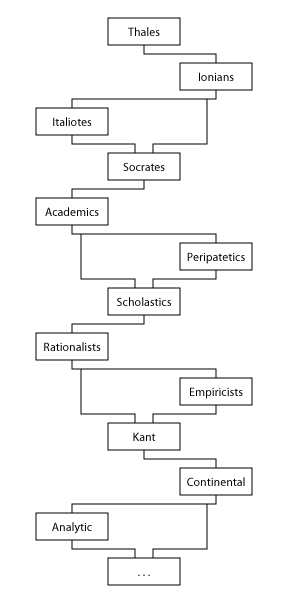

Also, this kind of back-and-forth between abstract and practical philosophy has been a pattern for pretty much the entire history of the whole thing:

-

A plea to the moderators of this siteI'm as anti-religious as they come and I think threads like this one are just as low-quality and (for lack of a better word) disruptive as the shallow little-reasoning religious threads are.

I generally think the best solution to that kind of problem is to ignore it (on the users' part; the mods have recourse to deleting on account of low quality or evangelism).

In which case I shouldn't even be making this post, but I am anyway. -

Who was right on certainty...Descartes or Lichtenburg?all of which reduces to Descartes’ cogito — Mww

Not quite. Instead of “I think, therefore I am”, you have “I experience something, therefore I and that something exist”. The having of some experience is what is primary; the existence of someone having that experience does follow immediately, but then so does the existence of something being experienced, and the nature or identity of the experiencer is just an uncertain as the nature or identity of the experienced. We don’t end up in a place where the whole world of experience is dubitable but the self is certain, like Descartes would have it.

We can be certain that an experience is being had by someone, but we as yet have no idea who that someone is; and we equally can be certain that an experience is being had of something, though we have no idea what that something is. All we are certain of is that an experience is happening. -

The Road to 2020 - American Electionsradical rule change [...] increasing the size of the Supreme Court — Hanover

The size of the Supreme Court is actually not fixed and has varied widely over time. It's a fairly recent tradition for it to have exactly 9 members all the time, and any President+Senate can change that whenever they feel like it, legally speaking.

I've been advocating recently that instead of trying to keep the court a specific size and worrying about when a Justice will die and so who will get a chance to appoint a new one, we should instead just allow the appointment of a new Justice by every new combination of President+Congress; in other words, every two years. I originally suggested every four years, as that would nearly match the rate in living memory (we'd have pretty much exactly the same court we have now if we had been doing that since GHW Bush), but checking what would have happened if that had always been the tradition, we would have run out of Justices entirely some time in the mid-20th century, so I bumped it up to every two years instead. If we had always been doing that, then we would currently have a court of 14 justices, 7 appointed by Democrats, 7 appointed by Republicans. -

Mathematicist Genesis@fdrake@Kenosha Kid@jgill glad to see you all talking about collaborating on this! I feel like I have a very very superficial understanding of most of the steps along the way, and you all have such deeper knowledge in your respective ways that I would love to see spelled out here.

I’m especially curious about the steps between SU groups, and excitations of quantum fields into particles. Like, I have a vague understanding that an SU group is a kind of space with a particular sort of matrix of complex numbers at every point in it, and I imagine that that space is identified with a quantum field and so what’s happening in those matrices at each point is what’s happening with the quantum field at that point, but I have no clue what the actual relationship between the quantum field states and the complex matrices is. -

Mathematicist GenesisMachine learning is fascinating, but kind of orthogonal to what I’m hoping yo accomplish in this thread. We have a black box example of all of this stuff available already: the actual universe. I want to sketch out a rough version of what’s going on in that black box, stepping up through sets, numbers, spaces, differentiable manifolds, Lie groups, quantum fields, particles, chemicals, cells, organisms, etc.

-

What is un-relative moral?It looks like if moral absolutes are real, it would serve as the best justification for moral universalism. Am I correct? — TheMadFool

Moral absolutism would necessitate that moral universalism be true, yes, but proving some moral principle is absolute is a bigger task than proving that whatever is moral is moral to everyone. So to prove moral absolutism you would pretty much have to prove moral universalism along the way... which is why absolutism necessitates universalism. -

What is un-relative moral?This is possible only if moral absolutism is true, right? — TheMadFool

Other way around: moral absolutism can only be true if moral universalism is true. But universalism can be true — every particular event can be non-relatively good or bad or permissible or impermissible etc — without moral absolutism being true — without every instance of a general kind of action always being good or bad etc regardless of circumstances. -

Who was right on certainty...Descartes or Lichtenburg?Lichtenburg, sort of.

All that is truly indubitable is that thinking occurs, or at least, that some kind of cognitive or mental activity occurs. I prefer to use the word "thought" in a more narrow sense than merely any mental activity, so what I would say is all that survives the Cartesian attempt at universal doubt is experience: one cannot doubt that an experience of doubt is being had, and so that some kind of experience is being had.

But I then say that the concept of an experience is inherently a relational one: someone has an experience of something. An experience being had by nobody is an experience not being had at all, and an experience being had of nothing is again an experience not being had at all. This indubitable experience thus immediately gives justification to the notion of both a self, which is whoever the someone having the experience is, and also a world, which is whatever the something being experienced is.

One may yet have no idea what the nature of oneself or the world is, in any detail at all, but one can no more doubt that oneself exists to have an experience than that experience is happening, and more still than that, one cannot doubt that something is being experienced, and whatever that something is, in its entirety, that is what one calls the world. So from the moment we are aware of any experience at all, we can conclude that there is some world or another being experienced, and we can then attend to the particulars of those experiences to suss out the particular nature of that world.

The particular occasions of experience are thus the most fundamentally concrete parts of the world, and everything else that we postulate the existence of, including things as elementary as matter, is some abstraction that's only real inasmuch as postulating its existence helps explain the particular occasions of experience that we have. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsWill you commit to a peaceful transfer of power after the election? — Reporter

We're gonna have to see what happens."

Get rid of the ballots and there'll be a peaceful … it won't be a transfer frankly it will be a continuation. — Trump

https://boingboing.net/2020/09/23/trumps-threat-get-rid-of-the-ballots-there-wont-be-a-transfer-frankly-there-will-be-a-continuation.html

-

What is un-relative moral?Just a small point of clarification for now:

The opposite of moral relativism is moral objectivism or universalism, not necessarily "absolutism".

Moral absolutism is the opposite of things like consequentialism, such as (for a Christian example for you) "situationism".

You can be a non-absolutist, like a consequentialist, while still being an objectivist or universalist, not a relativist. -

Mathematicist GenesisYou probably need to qualify this. Take the circle x^2+y^2=1 in the standard Euclidean plane and lengthen the scale on the x-axis, so that the circle becomes an ellipse. That's a "different coordinate system". — jgill

I'm not sure I understand what you mean here. You can describe the same circle with different coordinates in a distorted coordinate system like that; or you can describe a different ellipse with the same coordinates in that different coordinate system. I'm not sure which of those scenarios you're referring to.

I'm talking about the first scenario: the circle is unchanged, but different numbers map to its points in the different coordinate system, and the points can each be considered the equivalence classes of all different sets of numbers that can map to them from all coordinate systems.

I wish I had this site when I was at school, because I suspect that, with the right wording, you could make fdrake do a lot of your homework. — Kenosha Kid

Yeah @fdrake is awesome and I would love to see him continue what he was doing in this thread; or for someone else to take over where he left off. -

Where could I find a quietist philosopher or resource to defuse philosophical problems with quietismI think quietist philosophy is no different than any other topic done properly, in a critical rationalist way.

Critical rationalism means all you’re ever justified in saying on any topic is that the answer to a question is not such-and-such, only ever saying that it must be so-and-so to the effect that “so-and-so” just means “not-such-and-such”.

And yet there is an enormous amount that can be said on the topic of e.g. what ways empirical investigations have shown cannot be the correct physics, and what the remaining range of possibilities in physics are.

There is similarly an enormous amount to say about philosophy, even if what you end up doing is basically cataloguing in detail all the ways that various approaches to philosophy go wrong. -

"My theory of..."Ah but Banno put it in quotes, meaning he’s only MENTIONING the phrase, not USING it, and he’s only calling for the banning of people who use it, not those who merely mention it.

-

Do any philosophies or philosophers refute the "all is mind" position?I don’t necessarily mean rejecting, just not accepting without proof/evidence. Isn’t this what a default position should be? I shouldn’t automatically accept every idea I stumble across and then begin the process of disproving them all. — Pinprick

Think of it as analogous to how we treat behaviors in a liberal society; “doing something” is analogous to “believing something” here. If someone does something differently than you, that doesn’t automatically make them wrong; but neither does it automatically make you wrong. Neither of you has the burden to justify your ways to the other, nor any obligation to do as the other does if you can’t justify doing otherwise. Both ways of doing things are initially to be presumed fine, until something can be shown to be wrong with one; and even when something is found to be wrong with one way, that doesn’t automatically mean that the other way is obligatory, unless the other way is the only other possibility.

Also, you seem to imply that if a methodology leads to universal nihilism (rejection of everything forever), then the methodology is wrong. This isn’t warranted. — Pinprick

That implication is intended and warranted.

If such nihilism is true, then by its nature it cannot be known to be true, because to know it to be true we would need some means of objectively evaluating claims, so as to justifiably rule all such claims to be false. But the inability to make such objective evaluations is precisely what such a nihilistic position claims; at most, the nihilist can express their opinion that nihilism is true, but to be consistent, must agree to disagree with anyone whose opinion differs about that. In the absence of such a means of objective evaluation, it nevertheless remains an open possibility that nothing is real, or that nothing is moral. But we could only ever assume such an opinion as baselessly as nihilism would hold every other opinion to be held.

In the strictest sense, I agree that there might not be anything real or moral at all. But all we could do in that case is one of two things. We could either baselessly assume that there is nothing real or moral at all, and stop there, simply giving up any hope of ever finding out if we were wrong in that baseless assumption. Or else, instead, we could baselessly assume that there is something real and something moral — as there certainly inevitably seems to be, since even if you deny their objectivity some things will still look true or false to you and feel good or bad to you — and then proceed with the long hard work of figuring out what seems most likely to be real and moral, by attending closely and thoroughly to those seemings, those experiences.

But note that I am not saying to take any particular answer on faith, neither to questions of what is real nor to questions of what is moral. I am saying only to trust that there are some answers or others to be found to all such questions, even if we haven't found them yet. I am not even saying that any such answers definitely will ever be found. I'm not saying that success in the endeavor of inquiry is guaranteed, just to always assume that it is possible rather than (just as baselessly) assuming that it is impossible. I am only saying that we stand a much better chance of getting closer to finding answers, if anything like that should turn out to be possible, if we try to find them, proceeding as though we assume that there is something to be found, than if we just assume that there is not, and don't even try.

Because if you accept nihilism rather than objectivism, then if there is such a thing as the right opinion after all, you will never find it, because you never even attempt to answer what it might be, and you will remain wrong forever.

There might not be such a thing as a correct opinion, and if there is, we might not be able to find it. But if we're starting from such a place of complete ignorance that we're not even sure about that — where we don't know what there is to know, or how to know it, or if we can know it at all, or if there is even anything at all to be known — and we want to figure out what the correct opinions are in case such a thing should turn out to be possible, then the safest bet, pragmatically speaking, is to proceed under the assumption that there are such things, and that we can find them, and then try. Maybe ultimately in vain, but that's better than failing just because we never tried in the first place.

So anything that ends up implying nihilism has to be rejected along with nihilism via modus tollens (if you deny the consequent of an implication you have to deny the antecedent as well). The kind of justificationist methodology I argue against here implies nihilism, so we must reject it. Funny enough, solipsism implies effective nihilism too, so that is also a reason to reject it as well. -

Why special relativity does not contradict with general philosophy?For instance, I think that most physicists would probably reject moral objectivism, whereas most philosophers I've spoken to believe it is true, and I do think that relativity, while having nothing to do with morality, did impact how we think generally about objective frameworks. — Kenosha Kid

Crazy religious nuts object to relativity in physics because they think it will lead to moral relativism. Don’t give them any ammo. -

Mathematicist GenesisResurrecting this thread to get feedback on something I've written since, basically my own summary of what I hoped this thread would produce, and I'd love some feedback on the correctness of it from people better-versed than me in mathematics or physics:

Mathematics is essentially just the application of pure logic: a mathematical object is defined by fiat as whatever obeys some specified rules, and then the logical implications of that definition, and the relations of those kinds of objects to each other, are explored in the working practice of mathematics. Numbers are just one such kind of objects, and there are many others, but in contemporary mathematics, all of those structures have since been grounded in sets.

The natural numbers, for instance, meaning the counting numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, ...}, are easily defined in terms of sets. First we define a series of sets, starting with the empty set, and then a set that only contains that one empty set, and then a set that only contains those two preceding sets, and then a set that contains only those three preceding sets, and so on, at each step of the series defining the next set as the union of the previous set and a set containing only that previous set. We can then define some set operations (which I won't detail here) that relate those sets in that series to each other in the same way that the arithmetic operations of addition and multiplication relate natural numbers to each other.

We could name those sets and those operations however we like, but if we name the series of sets "zero", "one", "two", "three", and so on, and name those operations "addition" and "multiplication", then when we talk about those operations on that series of sets, there is no way to tell if we are just talking about some made-up operations on a made-up series of sets, or if we were talking about actual addition and multiplication on actual natural numbers: all of the same things would be necessarily true in both cases, e.g. doing the set operation we called "addition" on the set we called "two" and another copy of that set called "two" creates the set that we called "four". Because these sets and these operations on them are fundamentally indistinguishable from addition and multiplication on numbers, they are functionally identical: those operations on those sets just are the same thing as addition and multiplication on the natural numbers.

All kinds of mathematical structures, by which I don't just mean a whole lot of different mathematical structures but literally every mathematical structure studied in mathematics today, can be built up out of sets this way. The integers, or whole numbers, can be built out of the natural numbers (which are built out of sets) as equivalence classes (a kind of set) of ordered pairs (a kind of set) of natural numbers, meaning in short that each integer is identical to some set of equivalent sets of two natural numbers in order, those sets of two natural numbers in order that are equal when one is subtracted from the other: the integers are all the things you can get by subtracting one natural number from another. Similarly, the rational numbers can be defined as equivalence classes of ordered pairs of integers in a way that means that the rationals are the things you can get by dividing one integer by another.

The real numbers, including irrational numbers like pi and the square root of 2, can be constructed out of sets of rational numbers in a process too complicated to detail here (something called a Dedekind-complete ordered field, where a field is itself a kind of set). The complex numbers, including things like the square root of negative one, can be constructed out of ordered pairs of real numbers; and further hypercomplex numbers, including things called quaternions and octonions, can be built out of larger ordered sets of real numbers, which are built out of complicated sets of rational numbers, which are built out of sets of integers, which are built out of sets of natural numbers, which are built out of sets built out of sets of just the empty set. So from nothing but the empty set, we can build up to all complicated manner of fancy numbers.

But it is not just numbers that can be built out of sets. For example, all manner of geometric objects are also built out of sets as well. All abstract geometric objects can be reduced to sets of abstract geometric points, and a kind of function called a coordinate system maps such sets of points onto sets of numbers in a one-to-one manner, which is hence reversible: a coordinate system can be seen as turning sets of numbers into sets of points as well. For example, the set of real numbers can be mapped onto the usual kind of straight, continuous line considered in elementary geometry, and so the real numbers can be considered to form such a line; similarly, the complex numbers can be considered to form a flat, continuous plane. Different coordinate systems can map different numbers to different points without changing any features of the resulting geometric object, so the points, of which all geometric objects are built, can be considered the equivalence classes (a kind of set) of all the numbers (also made of sets) that any possible coordinate system could map to them. Things like lines and planes are examples of the more general type of object called a space.

Spaces can be very different in nature depending on exactly how they are constructed, but a space that locally resembles the usual kind of straight and flat spaces we intuitively speak of (called Euclidian spaces) is an object called a manifold, and such a space that, like the real number line and the complex number plane, is continuous in the way required to do calculus on it, is called a differentiable manifold. Such a differentiable manifold is basically just a slight generalization of the usual kind of flat, continuous space we intuitively think of space as being, and it, as shown, can be built entirely out of sets of sets of ultimately empty sets.

Meanwhile, a special type of set defined such that any two elements in it can be combined through some operation to produce a third element of it, in a way obeying a few rules that I won't detail here, constitutes a mathematical object called a group. A differentiable manifold, being a set, can also be a group, if it follows the rules that define a group, and when it does, that is called a Lie group. Also meanwhile, another special kind of set whose members can be sorted into a two-dimensional array constitutes a mathematical object called a matrix, which can be treated in many ways like a fancy kind of number that can be added, multiplied, etc.

A square matrix (one with its dimensions being of equal length) of complex numbers that obeys some other rules that I once again won't detail here is called a unitary matrix. Matrices can be the "numbers" that make up a geometric space, including a differentiable manifold, including a Lie group, and when a Lie group is made of unitary matrices, it constitutes a unitary group. And lastly, a unitary group that obeys another rule I won't bother detailing here is called a special unitary group. This makes a special unitary group essentially a space of the kind we would intuitively expect a space to be like — locally flat-ish, smooth and continuous, etc — but where every point in that space is a particular kind of square matrix of complex numbers, that all obey certain rules under certain operations on them, with different kinds of special unitary groups being made of matrices of different sizes.

I have hastily recounted here the construction of this specific and complicated mathematical object, the special unitary group, out of bare, empty sets, because that special unitary group is considered by contemporary theories of physics to be the fundamental kind of thing that the most elementary physical objects, quantum fields, are literally made of. -

Do any philosophies or philosophers refute the "all is mind" position?So for the case at hand, we don’t have to worry about the mere POSSIBILITY of solipsism being true; sure, it might be, but so might its negation. Both of those are possibilities. Which seems more likely to be true to you? Probably its negation. And you’re free to believe that; you don’t have to defeat solipsism first. You can just ignore it, until such time as someone’s disproves its negation. And “it might not be true, it’s possibly false” is not a disproof.

-

Do any philosophies or philosophers refute the "all is mind" position?The idea that an idea has to be proven wrong in order to be wrong is wrong. In order for an idea to even be considered plausible, or worth considering, it must have some justified explanatory power. — Pinprick

This is backwards. If you reject every possibility until it can be proven, then you reject everything by default and then have nothing with which to prove anything from, leaving you rejecting everything forever.

The only way to rationally choose between possibilities is to tentatively admit all of them until they can be disproven. That does mean you never end up narrowing down to only one possibility, the definite absolute truth, but it at least gives you somewhere to start and some way to make progress from there, unlike the alternative. -

The Death of Roe v Wade? The birth of a new Liberalism?But if a socially conservative majority of justices decide to rule against the legality of abortion in some case brought before them, on the grounds that a fetus is a person (say because it is demonstrably human and all humans are presumably persons), then that sets judicial precedent for fetuses being persons and so renders abortion legally equivalent to murder.

There doesn’t have to be a law specifically saying that fetuses are persons if the court just interprets existing laws with an assumption that they are, which thus creates common law saying that they are. -

Why special relativity does not contradict with general philosophy?There are relativists of all kinds in philosophy, thoughts I do think they’re generally wrong and counter to the spirit of philosophy itself.

Relativity in physics though is not relativist in that sense. There is still an objective reality, it’s just that certain facets of it are relative to other things. It’s like how realizing that the world is round means that “down” is relative, but it doesn’t mean there are no objective directions at all. Relativity in physics is like that: lengths and durations and so on vary from observer to observer, but there are still objective physical realities underlying those things, which all observers can agree upon.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum