Comments

-

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageHey, don't be pessimistic about it. Are you going to publish? — Tarrasque

I've self-published on the internet already (link in my user profile), but I've yet to confirm that a single person has even read the entire thing, so I'm really lacking in confidence that anyone would want to pay to read it, when they won't even read it for free.

The only negative thing I would say about the sort of "theory-of-everything" approach you have is that it requires a reader to sacrifice more of their initial beliefs than a single, cohesive "theory-of-one-thing." It's a lot harder to convince someone to adopt a wholly unique theory-of-all-issues than, say, simply fit a meticulously argued panpsychism into their belief system. But, obviously, trying to fit it all together is an impressive undertaking. — Tarrasque

One of the reasons I ended up doing this systemic approach was because it seems one can't argue for one position in one subtopic without bringing up other subtopics. This thread is just about philosophy of language, specifically moral language, but we've already had to shy away from tangents leading off into philosophy of mind, will, ontology, and of course other, more normative fields of ethics. Everything has implications on everything else, and when studying everything I found those implications traced down to a few core principles. So I start with the reasons to adopt those few core principles instead of others, and then explore the implications of those on everything else, since if I started in any one place I'd end up tracing it back to those principles which in turn would raise a bunch of "but what about this other field then" questions anyway.

Tomorrow is my birthday and I'm going out of town for it, so I probably won't have time to reply to the rest of this until Sunday. Looking forward to it. -

Aliens!So where are all the dimming stars we should be seeing from all the alien civs building all these solar collector swarms and habitats? — RogueAI

If you were to star-lift a star, where would you put all the removed matter? Maybe... just dump it all in big lumps in orbit close to the star? Like a bunch of, what would you call them... hot Jupiters, maybe?

Have we been finding a bunch of them around, or no? -

Was Friedrich Nietzsche for or against Nihilism?Nietzsche saw nihilism as something to be overcome: that people would rightly reject religious doctrine and traditional beliefs and values, and having nothing left, fall into nihilism, but that that was a phase that needed to be overcome, building something new and better in the place of those old rejected views.

And that about the only thing I agree with him about, what with the rejection of both faith and nihilism being the core of my entire philosophy. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageI do think that people are warranted in believing what seems to be true to them, until it is defeated by a stronger reason to believe otherwise. — Tarrasque

:clap: :point:

Our methods should probably depend on what it is we're trying to learn truth about. — Tarrasque

:100: :up:

I was disputing Pfhorrest's version of prescriptivism, which makes claims to its own unique sort of cognitivism, even though how he has described it so far is not compatible with the tenets of cognitivism I mentioned above. — Tarrasque

In the broader sense of “true” instead of which I’m using the word “correct” for disambiguity (from senses of “truth” that imply description), it does. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageExcited to get into epistemology and ontology threads when they come up. Are you a mod here or just a very involved user? — Tarrasque

I’m not a mod, and I’m not even sure I’m very involved here compared to others. I haven’t even been here a year so far. I’m just some isolated guy who wants to actually talk to other people about the philosophical system I’ve been brewing for a decade instead of just writing it down in my book that nobody will ever read.

At face value, this seems patently false to me. Ex,

"Going to the gym today is good but I don't intend to go to the gym today."

Often, we recognize that things are good, but nonetheless intend otherwise. Conversely, it can't be said that we often recognize things to be true and yet believe otherwise. Alternatively, consider the guilty meat eater:

"Eating meat is wrong but I still intend to eat meat."

He may have come across a moral argument that convinced him that being a vegetarian is the morally right thing to do. He may still be a slave to his vices, or be insufficiently motivated by moral reasons. Nothing seems overtly paradoxical about this. — Tarrasque

The distinction I make between desire and intention is important here. Being a slave to your vices is a case of your intentions not being causally effective on your actions, e.g. you mean to do something, you think you ought to, you resolve to do that, but despite that you just can't help but do otherwise, because other desires besides the desire you desire to desire override it.

This is analogous to mirages and optical illusions. Sometimes you perceive something, and you know that perception is false, you judge that your perception is incorrect, but that doesn't stop you from perceiving it anyway. You perceive something you don't believe. Likewise you can desire something you don't intend. As just like you might not help but act on some perceptions even though you disbelieve them (e.g. recoiling from a scary hallucination you know isn't real), so too you might not help but act on some desires you don't intend to.

Once again, natural language is a little sloppy, and I know this distinction is not nearly always maintained in ordinary speech, but in the ways that I'm distinguishing the concepts, to intend something and to think it's good are identical in the same way that believing something and thinking it's true are.

In the case of the gym example, if you honestly don't intend to go to the gym, rather than just not desiring to and expecting those slothful desires to win out, then that would suggest that you think there is some greater good than going to the gym that you would be neglecting, so you think you going to the gym today is not actually good (because in the full context you think doing so would be worse than not doing so), even if you think going to the gym generally is good.

What I am concerned with is not the reason why a subject thinks something ought to be the case. I am concerned with what renders them correct, independently of whether they know they're correct or not. It is not an issue of justification. It is an issue of truthmakers. — Tarrasque

I get that, and that's what I'm meaning to address. The truthmakers of moral claims, on my account, are the appetitive experiences of things seeming good or bad in the first-person. Not the sensory experiences of other people seeming, in the third person, to be having experiences of things seeming good or bad. Just like the truthmakers of factual claims, on my account, are the sensory experiences of things seeming true or false in the first-person, not the sensory experiences of other people seeming, in the third person, to be having experiences of things seeming true or false.

This avoids solipsism or egotism, as I expect you'll object next, because you can either trust other people that they had the first-person appetitive experiences that they claimed to have, or go have those same experiences yourself if you don't trust them. In either case, it's that first-person experience that is the truth maker, not any third-person account of a fact that someone's brain is undergoing some process.

So, is everybody's appetite given equal weight? Bloodlust or sadism can be considered appetites. Some people have these appetites. How does your metaethical theory account for these? Are they not ruled out for being in the minority? If half of all people had bloodlust as a base appetite, how would this change ethics? — Tarrasque

Who or how many people is not relevant. But in any case bloodlust or sadism as usually defined would be desires, not appetites. Someone desires to kill or hurt someone else. That doesn't mean that a complete moral account has to grant them what they desire. But whatever raw experiences they're having that give rise to those desires, whatever kind of psychological pain or whatever may be behind it, those are appetites, and need to be satisfied.

The thing about appetites, unlike desires or intentions, is that they definitionally cannot conflict, because they are not about states of affairs, just experiences. The trick is to come up with some state of affairs that satisfies all those experiences. Just like sense-observations cannot conflict, only perceptions or desires can, because the latter are about states of affairs, while the former are just raw data, and the trick in science is to come up with some state of affairs that somehow satisfies all that sense-data.

This is well put, and generally true. As a principle of epistemology, specifically constrained to physical matters, verificationism is about as good as it gets. What I don't see as plausible is the jump from "we can't possibly know everything" to "there is nothing outside what we can know." In fact, they seem to be borderline contradictory. If there is nothing outside what we can know, what are we failing to know when we can't possibly know everything? — Tarrasque

Think of it like this: There are no things that we could never know, but there are infinitely many things that we could know. Because we're starting with a finite amount of things that we do know, we will always have merely a finite number of things that we do know, and consequently infinitely many things that we still don't know. But all those infinitely many things we don't know are still part of the set of things we could know.

Consider natural numbers for analogy. There is no natural number that could not, in principle, be counted up to. But we can never finish counting all of the natural numbers. No matter how many we count, there will still be infinitely many that we haven't yet counted. But those are still nevertheless in principle countable: if we keep counting we will eventually count any number you'd care to name, but there will always still be more that we haven't counted yet.

This is great. I like this parable a lot, and wish I had thought of a comparable example myself. Let's imagine that, for whatever reason, communication between these three blind men is impossible. Clearly, they are all restricted in the ways in which they can examine the elephant. If the only consistent consensus each can form is with himself, why is his judgement about the elephant not accurate? Snake-man can only verify a snake, tree-man can only verify a tree, and rope-man can only verify a rope. If verificationism about truth is correct, none of these men are wrong. Verificationism would assert that, in such an allegorical case, there would be no underlying fact of "elephant." If they cannot confirm an elephant, there is no elephant. Does this not seem as intuitively false to you as it does to me? — Tarrasque

If there was truly absolutely no way in principle to ever tell anything about the object they're feeling than the things they "mistakenly" feel, then yes, those things would actually not be mistakes. But such an impossibly absolute separation of all experiences would also be them existing in literally separate worlds, on my account, so it's not all that weird that one of those worlds would have a snake, one a tree, etc.

It's important to keep distinct things that are "practically impossible" and things that are really and truly impossible in principle. There are lots of cases where it's "practically impossible" to verify something, but still actually possible in principle, and it's that in-principle that makes the difference. If you extend the "practical impossibility" to ridiculous lengths, you end up getting ridiculous-sounding conclusions, and if you take it impossibly far all the way to complete actual impossibility, you get ridiculous conclusions like these three men existing in actually separate worlds.

Hard-core physics already deals all the time with things that are practically impossible but possible in principle when looking to resolve apparent problems with its models. Like, information seems like it could be lost in black holes, which breaks some fundamental principles of quantum physics about the conservation of information, but a possible solution is that a particle falling across the event horizon causes (to be loose and visual about it) ripples on the horizon which affect the emission of Hawking radiation from that horizon, allowing in principle the information about what fell into the black hole to be constructed from the "completely random" Hawking radiation, via the implications of that about the ripples made in the horizon by the in-falling stuff. Of course nobody in practice is ever going to be able to gather enough data about the Hawking radiation coming out of a black hole to figure out some particular item that fell into it aeons earlier, but in principle it's possible and that's enough to save the principle of information conservation.

It is important to remember that propositions need not deal only in utterances. We could, again, imagine that bugs have died in the shape of words on some piece of paper to form a valid modus ponens. Impression would play no role in our evaluation of it. — Tarrasque

In reading the message written in dead bugs, we necessarily interpret it as though it was an utterance. Part of what makes something an impression or an expression is the interpretation of the audience; really, it's more the audience's interpretation than the speaker's intention that conveys any kind of communication at all. A person makes noises with their mouth or marks on a paper and someone else sees or hears those and thoughts come into their mind in reaction, which may or may not have been the thoughts intended by the person who made those noises or marks, if (as in your example) there even was a person who made them.

So if you read what seems to be an impression written in dead bugs that happen to have died in that pattern, and you read it as an impression, not just as a meaningless pattern of dead bugs, then to you it is an impression.

My systemic objection here would be that classical logic works very well for us. An alternative account being merely internally consistent(if yours in fact is) does not give us sufficient reason to switch, universally, our understanding of classical logic to Pfhorrest logic. We would need a compelling case to conclude that when your position produces errors in classical logic, we ought to discard classical logic rather than your position. — Tarrasque

I don't mean my system of logic to contradict classical logic at all. I mean my system to be merely a way of encoding things in more detail, that can then be useful in making inferences.

It's like the switch from simple subject-predicate syllogisms to properly quantified modern predicate logic. Before modern predicate logic, a sentence like "every mouse is afraid of some cat" would be logically decomposed into the quantifier "every", the subject "mouse", and the predicate "is afraid of some cat". But that leaves it ambiguous as to whether there is one particular cat of whom all mice are afraid, or whether each mouse is afraid of one cat or another but not necessarily all the same one. In modern predicate logic, we would instead break it down into either "there is some cat such that for every mouse, the mouse is afraid of that cat", or "for every mouse, there is some cat such that the mouse is afraid of that cat". All the rules of logic that applied before still apply, but now we're capable of distinguishing these two meanings from each other, and reasoning about them differently as appropriate.

Likewise, in my logic, every ordinary indicative descriptive sentence "x is F" can be turned into "is(X being F)" and all the same rules of logic will apply to them. But if there was another sentence "x is G" where G is a predicate meaning that what it's applied to ought to be F, instead of treating that as a completely unrelated sentence, we could render it as "be(X being F)". You can do the exact same rules of logic to that re-encoding as you would with "x is G", but you can also see relationships between that statement and the statement "x is F" and generally other statements about x being F.

Sure, "Close the door!" and "The door ought to be closed." and "The door is closed." and "You should believe that the door is closed." all can be thought of as different forms of the same primitive idea, "the door being closed." Can we conclude from this that the meaning of all of the above is identical? Can they be freely interchanged with each other, and all be represented by the same variable in a deduction? Formal — Tarrasque

I certainly don't think those are all identical in meaning or freely interchangeable. "is(S)" and "be(S)" mean very different things, they just have in common the state of affairs S. "be(x F'ed)" and "be(you F'ing x)" are also different statements, even though the later implies the former.

This is also where I will further explore your distinction between "truth" and "correctness." Typically, logic deals in propositions that can be true or false. Validity is a property of arguments that lies in the relationship between premises and conclusions, where an argument is valid only if the truth of the premises entail the truth of the conclusion. This relationship of entailment is core to logic. You consider the domain of what can be true to solely contain the domain of what is physical. Other domains that we might normally consider to be capable of bearing truth, such as matters of mathematics, logic itself, morality, and theology, you consider merely "correctness-apt."

You do not seem to object to logical arguments being built around "correctness" in the same way we might normally use "truth." That you would consider a moral modus ponens to be capable of validity at all requires "correctness" to have the same relationship with logical entailment that traditional "truth" does. It seems that the concept of truth, as typically employed, you have replaced wholesale with this notion of "correctness." Under your account, "truth" has therefore been reduced in scope to refer merely to "physical truth." It appears, then, that rather than identifying a supercategory above and including our typical term "truth," you have introduced a subcategory: "physical truth." This is why I would suggest abandoning the "truth/correctness" dichotomy entirely, and just referring to "truth" and "specifically physical truth." If correctness does everything that truth does in logic, it just is truth. We can cast aside "all truths are physical truths, all else is correctness" in favor of "some truths are purely physical truths, and these are relevantly different from nonphysical truths." Since you don't espouse a correspondence theory of truth, you don't have to account for anything that nonphysical truths correspond to. This change would not be problematic for your theory at all. — Tarrasque

I don't have any problem with talking about "truth" in the broader sense that you are. I only substitute "correctness" because to some people, "truth" implies descriptiveness, and I want to avoid confusion with them. You're absolutely right that there's two concepts here, a narrower one and a broader one, and I don't have any particular attachment to the terms used for them, just so long as they are distinguished from each other.

The narrower concept, though, is not specifically "physical truth", but "descriptive truth". On my physicalist account, those are identical, but for the purposes of logic, they don't have to be. Saying that there exist some abstract moral objects is a descriptive, but not physical, claim. It would be made true by reality being a certain way, by it being an accurate description of reality. Likewise any kind of claim about the existence of any nonphysical things: they're still claims that things are, really some way. There are other kinds of claims that don't purport to describe how reality is at all, though; most notable, prescriptive claims, that something ought to be, morally. I think that those kinds of claims can also be true in a sense, but a non-descriptive sense; hence I try to say "correct" instead of "true" to avoid possible implications of descriptivism, but I don't mind at all when others do otherwise.

(Besides its conflict with my physicalism, I would still object to moral non-naturalism because it's still a form of descriptivism, and so still tries to draw an "ought" from an "is": there are these abstract moral objects, therefore things ought to be like so-and-so.)

I don't think that to say something is objective means it is incontrovertible. — Tarrasque

I didn't mean that at all. I meant only an expectation that it won't be controverted. If you expect that something will be contradicted by later observations, or is already contradicted by observations from a certain perspective, then you don't think it's objectively true. So if you do think it's objectively true, then you expect that it won't be and isn't already contradicted, from any perspective. That says nothing at all about your degree of certainty in that expectation, just that, on the overall balance of things, that is your expectation.

The idea that there are only empirical truths or definitional truths has its roots in "Hume's Fork," which asserted that truth neatly divides into the two camps of "matters of fact" and "relations of ideas." If you prefer, we could accurately describe the two camps as "synthetic a posteriori" versus "analytic a priori." I take it you believe something like this, since you said at the start of our discussion that mathematical truths are merely definitionally true relations of ideas. — Tarrasque

Something like it yes, but not exactly that. My fork would have three tines. In the middle are the relations between ideas, without any attitude toward them, neither claiming those ideas are correct to describe reality with nor correct to prescribe morality with, just that those ideas have those relations to each other. Then on one side are claims that those ideas are descriptively correct, i.e. "true" in the narrower sense; and on the other side are claims that those ideas are prescriptively correct, i.e. "good". I think both of those kinds of claims can be objectively evaluated by appeals to shared experiences, and the same kind of logic can be done to both, because the logic hinges entirely on the relations between the ideas, not on whether they are fit for description or prescription.

As long as information exists in the universe, it is empirically verifiable in principle? What about information that is moving away from us faster than the speed of light, at the edge of the observable universe? It is physical, yet empirically unobservable to us. Same with matters of the past - we are dealing with imperceptible matters of fact. If I say "Charlemagne had an odd number of hairs on his head," I might be correct on a guess. What would render me correct? If Charlemagne did, in fact, have an odd number of hairs on his head. Surely you wouldn't believe it impossible that Charlemagne might have had an odd number of hairs on his head? If you were to claim that it would be impossible for me to sufficiently justify a belief that he did, I would agree. However, holding these things to be undefined seems a harder bullet to bite than just admitting we can't know everything. Mystery is an aspect of the human condition, and we ought to become accustomed to it. — Tarrasque

I think the thing I said earlier in this post about distinguishing practical possibility from in-principle possibility addresses this.

If everybody had to settle on verificationism about truth before even engaging in description — Tarrasque

Sorry, I didn't mean that it's not possible to do description without first agreeing with verificationism, just that questions like whether or not to adopt things like verificationism are logically prior to any investigation about the world.

You might be interested in my previous thread on The Principles of Commensurablism, which is all about my basic philosophical framework that this meta-ethics / philosophy of language is in the context of.

(I spent that entire thread trying to disengage with Isaac and never got around to actually presenting an argument for those principles, but if you want to ask about them over there, I will).

So, if we stipulate that nobody besides me and the other woman would ever find out about it, cheating on my partner would be morally permissible? — Tarrasque

The practical vs in-principle thing applies here again, and is basically the difference between "would" and "could". But taking this as an example situation, if nothing bad could in principle ever befall your partner because of your actions -- if there was no chance of bringing home an STD, or of you abandoning or growing more distant from your partner over this other woman, or anything like that, if you and your partner's relationship went completely unchanged, other than her being mad at you -- would you really have done something wrong, or would she just be unjustifiably angry? Sure her being angry is in itself a bad thing, but anyone can be angry about anything, and that doesn't automatically make the thing bad; my girlfriend gets angry if I put the spoons handle-down instead of handle-up in the dish drainer, but that doesn't make it morally obligatory to do it her way.

I know I'm weird in not sharing the inherent sense of outrage about "infidelity" that other people have, and it's not because I want to run off and do it with other people myself, but because I'm just honestly not a possessive person. I've been in open relationships before and not felt jealous, unless it actually had negative consequences for me (like, she wants to go spend more time with him and leave me alone and lonely). If you got rid of all the negative consequences -- which may not always, in practice, actually be possible -- then I don't see how it would be a genuinely bad thing.

To argue that it could not be the case just because it could not be verified is unconvincing. — Tarrasque

This is where a lot of my core principles come from. When we get down to questions that we cannot possibly find an answer to, but cannot help but implicitly assume some answer or another by our actions, we have to assume whichever way is most practically useful to finding other answers. I rule out solipsism, egotism, all kinds of relativism and subjectivism, appeals to faith, authority, popularity, intuition, all kinds of transcendentalism, justificationism, and the reduction of "is" to "ought" or vice versa, all on those grounds: those are things we have to figure out logically prior to investigating the world, that an investigation of the world can't answer but must assume answers to, so we only have practical reasons to assume one way or another, and any assumptions that would leave us unable to proceed with any further investigation have to be rejected, and their negations assumed instead. Which negations are the core principles all of this is proceeding from, discussed in that other thread.

The explanatory power lies in the observation that we discuss moral facts the same way we discuss other facts. We debate, disagree, and use reason to draw conclusions from premises. When we disagree, we believe that one or both of us are incorrect — Tarrasque

My account expects exactly that, too. Those are features of moral universalism generally, not specifically of moral non-naturalism.

Postulating that when we say "slavery is wrong," we descriptively assign a property "wrongness" to an act "slavery," and do so either correctly or incorrectly, is easy. It reflects what we appear to be doing with moral language, prima facie — Tarrasque

There is the quite similar situation of the predicate "is true", or "is real". On my account, these kinds of predicates (wrong/right, false/true, bad/good, unreal/real, immoral/moral, incorrect/correct, etc) are not describing a real property of a real object, but a linguistic or mental "property" or a linguistic or mental "objects": they're saying what to think or feel about some idea or state of affairs. "Slavery is wrong" takes the idea of the state of affairs where slavery is happening and says to disapprove of it, in the same way that saying "slavery is real" takes the idea of the state of affairs where slavery is happening and says to expect to see it out there in the world.

The only substantive objection you've offered to seeing things this way is the argument from queerness, which just asserts that moral facts seem too weird to exist. That's not something that would deter a pragmatist. — Tarrasque

It's not just the argument from queerness, but a more general physicalism (there are practical reasons for both realism and empiricism, which amount to physicalism, which rules out the existence of non-physical objects), and also an even more general non-descriptivism (there are practical reasons to reject reducing "is" to "ought" or vice versa, which rules out translating moral utterances to descriptions of reality, be it a natural or non-natural part of it). -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageLockdown, eh? If you're in America right now, my heart goes out to you. — Tarrasque

I am, and thanks.

Most utterances have both an expressive and impressive aspect, do they not? — Tarrasque

Impressions generally imply expressions, but not vice versa. You can merely express your opinions without necessarily impressing them on anyone.

What significance do impression and expression have? — Tarrasque

Expressions aren’t claims of objective truth — they’ll not propositions, as in they’re not proposing anything to anyone. They’re just showing something about one’s own mind. The main importance for meta-ethics is to distinguish my view from expressivism, where a major difference is that I don’t think moral claims are just expressing desires, but rather impressing intentions; which also implies an expression of intention, which intentions also imply some desires, but it’s more than just an expression of desire.

Impression and expression also clear up Moore's paradox, as I explained earlier. It seems paradoxical to say "x is true but I don't believe x", even though it's totally possible to disbelieve something that is actually true, and my explanation is that saying "x is true" impresses and therefore also expresses belief in x, which then contradicts the expression of disbelief, "I don't believe x".

The moral equivalent of that paradox would be the sentence "x is good but I don't intend x". It seems to me that what you intend and what you think are good are as inseparable as what you believe and what you think is true. It is possible to intend other than what is good, just like it's possible to believe other than that is true, but in saying something is good you implicitly express your intention that it be so, and so contradict the attendant explicit expression of intention otherwise.

But just as saying "x is true" doesn't merely express belief -- it's different from just saying "I believe x" -- so too saying "x is good" doesn't merely express intention -- it's different from just saying "I intend x". The difference between those things, in either pair, is the difference between expression and impression. "x is good" differs from "I intend x" in precisely the same way that "x is true" differs from "I believe x".

My most basic "ought"(I ought to be fed) is grounded by an "is"(I have the brain state "hunger"). What is this relationship? Is it supervenience? Is it necessity? Is it equivalence? — Tarrasque

This is the issue that I've been having trouble communicating to Kenosha and Isaac. I don't hold these "oughts" to be grounded in any "is". We can give a descriptive account of the cause of someone feeling or thinking that something ought to be, just like we can give a descriptive account of the cause of someone feeling or thinking that something is, but that account is not the reason why they feel or think that. We don't have to know anything at all about brains to go to our appetitive experiences as the ground of our "oughts", any more than we need to know about brains to go to our sensory experiences as the ground of our "is"s.

In the latter case it's rather transparently the other way around: we learn descriptive facts about brains empirically, by relying on our sensations, our "is" experiences. If we then used our knowledge about brains, gained through sensory observation, to justify using sensory observation, that would clearly be circular reasoning. The reliance on sensory experience comes prior to any description of the brain. Likewise, on my account the reliance on appetitive experience as the ground for prescription comes prior to any description of the brain.

I infer from what you've said above("all the experiences anyone could have in any context") that what matters is not my appetite, but everyone's idealized appetite were they in my situation. — Tarrasque

I'm not sure this is an accurate account of my account, because there could be differences between people that would make them have different appetites in the same situation. A moral claim is objectively true if it accounts for all of those different appetites in all different circumstances. Just like a really objectively true descriptive claim about the color of an object has to account for people with different kinds of color vision and different lighting conditions.

Here, we have jumped the is-ought gap. — Tarrasque

Only seemingly, because of the misunderstanding hopefully cleared up two quote blocks ago.

According to verificationism, unknowable noumena(things-in-themselves) do not exist. Given this, it is unclear to me why you feel the need to distinguish between "the experience of our interactions with the world, what it does to us and what we do to it" and "direct access to the world." Verificationism would hold that an idealized version of the former is identical to the latter. — Tarrasque

It's precisely that "idealized" that makes the difference. We don't, and can't, have a complete account of the way that the entire (possibly infinite) world would be experienced by all (possibly infinitely many) kinds of being. We only have the way that bits and pieces of it are experienced by beings like us. So we can't just take "the whole world, independent of all experience" (that non-existent noumena) and hold it up against "our picture of what the world should be like". We can only compare "the way this bit of the world seems to us like it is" and "the way this bit of the world seems to us like it ought to be".

Now, let's return to sensations and perceptions. The thing of most note here is the concept of "beings like us." Let us apply your truthmaking method to its intended context: differences between the perceptions of humans. First comes the brute observation of the individual. This takes the form of me seeing a ghost. Second, we compare this to our ideal aggregate's experience. Beings like me, in the situation where I saw a ghost, would not see a ghost. This is a discrepancy between how beings like me(with proper function) perceive the world, and how I perceive it. Therefore, "I saw a ghost" is rendered false. — Tarrasque

You experienced something, which you interpreted to be a ghost. Other very similar beings in very similar circumstances did not experience anything that they interpreted as a ghost. Whatever the objective truth is, it will need to account for your experiences as well; we don't just throw out your experience of seeming to have seen a ghost, but we need to account for why it seemed to you like there was a ghost, but not to others. Is something different about you, even though you're very similar to the others? If something different about the circumstances, even though they're very similar to the ones you saw? Or are they actually experiencing the same thing that you are, but you're just interpreting that experience differently than them? Maybe you and they both experienced the same sight, but you interpreted it as a ghost, while they interpreted it as a lens flare.

Where this gets interesting is with the introduction of beings entirely unlike us. We can imagine aliens who perceive the world drastically different than we do. They could experience appetites and sensations wholly separate from the ones humans experience. Does this entail relativism about descriptive truth? Such an alien must compare their experience with beings like themselves, not beings like us. Their conjunct of all "true"(re: empirically verifiable to beings like them) propositions might overlap with ours, but there would be things we can verify that they cannot, and things they can verify which we cannot. Can a proposition like "objects take the form of shapes" be true-for-us but false-for-them, or even more confusingly, true-for-us but nonsense-for-them? Are neither of us lacking in our description of reality, since reality just is our relative ideal description? Or, are we both aiming at an underlying truth and coming away with only part of it? — Tarrasque

That last bit. The parable of the blind men and the elephant is the illustration I like to use here. Three blind men each feel different parts of an elephant (the trunk, a leg, the tail), and each concludes that he is feeling something different (a snake, a tree, a rope). All three of them are wrong about what they perceive, but the truth of the matter, that they are feeling parts of an elephant, is consistent with what all three of them sense, even though the perceptions they draw from those sensations are mutually contradictory.

My original intention in introducing this line of analysis was to apply the first issue of the Frege-Geach problem to your theory. If you are claiming that moral propositions serve not to report fact, but to perform an act of prescription, you are vulnerable to this issue. While in an atomic moral sentence(Stealing is wrong!) I may be prescribing something, in the antecedent of a conditional(IF stealing is wrong, then..) I am not prescribing anything. My utterance of this sentence does not commit me to an attitude on stealing. This puts the law of identity on fragile ground, as explained above. — Tarrasque

On my account, it's not only moral utterances but ordinary descriptive utterances that are impressing an attitude toward the idea in question. We normally take your symbolic propositions "A" and "B" to be, by default, full indicative sentences, like "x is an a" and "x is a b" for instance. On my account, we abstract out the indicative-ness, the descriptive-ness, of those sentences, and deal with the gerund states-of-affairs "x being an a" and "x being a b". Then we can re-apply that indicative-ness/descriptive-ness, or instead apply an imperative-ness/prescriptive-ness, and the underlying logic goes unchanged.

So, given those gerund states-of-affairs above, this is the underlying syllogism:

P1. A

P2. A -> B

C. B

Spelled out, that reads (ungrammatically, because these are so far incomplete sentences) "x being an a, and x being an a implies x being a b, therefore x being a b".

To get the ordinary indicative/descriptive type of syllogism, we could instead write:

P1. is(A)

P2. A -> B

C. is(B)

Spelled out, that reads "x is an a, and x being an a implies x being a b, therefore x is a b".

We could instead make an imperative/prescriptive variation on it:

P1. be(A)

P2. A -> B

C. be(B)

Spelled out, that reads "x ought to be an a, and x being an a implies x being a b, therefore x ought to be a b".

This works perfectly fine in your brother-stealing example, because "x being an a" does imply "x being a b" in that case (so to speak; getting your brother to steal does imply stealing happening). But in the stealing-cheating example, I figured you didn't mean the ordinary English version to suggest that it is not possible to steal without cheating, only that the badnesses of them are connected. If you didn't mind that implication, then the above formalization would still work just fine: x ought to be not stealing, and x not stealing implies x not cheating, therefore x ought to be not cheating.

But if not, then you wouldn't want to translate that second premise as "x not stealing implies x not cheating" (gerund, equally applicable to descriptions or prescriptions, just stating a relationship between those states of affairs), but rather as "'x ought to be not stealing' implies 'x ought to be not cheating'". Symbolically, that would then be:

P1. be(A)

P2. be(A) -> be(B)

C. be(B)

If you are using supererogatory to merely mean "not obligatory," this is idiosyncratic. It means "above and beyond the call of duty" or "to a level far exceeding what is obligatory." I'm not one to argue about the definitions of words, as they mean what we want them to mean, but if you are going to use a customized version of a word, it is usually best to clarify before employing it. — Tarrasque

I didn't realize I was using a customized version of the word; I honestly just thought "supererogatory" was the deontic equivalent of "contingent". Doing some further research now prompted by this, I see that the word I really want is "omissible". I'll make sure to use that instead from now on, and change where I've mis-used "supererogatory" in the past where possible.

"Knowing this particle's current position, what is its current speed?"

The answer to this question is empirically unverifiable, in principle. By measuring the particle's position, we necessarily prevent ourselves from verifying its speed. Must we conclude that the question is nonsense? This seems especially unintuitive when we consider that we could have chosen to measure the particle's speed instead. If we had done so, its position would be unknown to us. Can a question about a physical matter of fact become nonsense moments later? If we are verificationists, we must concede that at the time of measuring the particle's position, to ask of its "speed" is nonsensical, referring to a property that does not exist. This is certainly not what physicists conclude here. Rather, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle establishes that there are physical matters of fact which are empirically unverifiable. — Tarrasque

Quantum physics is full of different interpretations, so I'm cautious to speak authoritatively about what all physicists think, but as I understand it, the uncertainty principle doesn't just say that we can't know position and speed at the same time, but that to the extent that we measure one, the other becomes literally undefined. A particle with a definite momentum has no definite position; its position is actually smeared out across space.

Defining verificationism without reference to a separate truth seems problematic. Why do we not appeal to the consensus of what we have, in fact, empirically verified? Well, because we know our methods are flawed. We must instead appeal to the consensus of our "idealized" methods. An idealized method is one where any mistakes we make are eliminated. A mistake is an inaccuracy. An inaccuracy to what? — Tarrasque

To other observations. We're (rightly) cautious about the accuracy of our present beliefs because we haven't made all of the observations (and never can), and there may be ones that contradict what we presently believe. To assert that something is objectively true is to assert that there won't ever be any contradictory observations. We can never know that with certainty, of course, but we can think it is so, at least tentatively.

Causality cannot be proven true empirically. Are questions about causality nonsense? Our investigations into the material world are predicated on all sorts of assumptions that are, themselves, empirically unverifiable. I am hard pressed to imagine us building a search for truth atop a foundation of nonsense. — Tarrasque

Causality, like physicality, is part of the background assumption of objectivity that we have to make in order to go about the process of investigating what is real. We can't empirically prove that anything is objectively real, either, but the question of whether anything is objectively real is prior to the empirical investigation. Likewise, the question of whether anything causes anything else. Empirical investigation helps us sort out what kinds of things cause what other kinds of things, on the assumption that things cause other things in the first place and all our experiences aren't willy-nilly incomprehensible.

The past is empirically unverifiable. Whether or not a certain dinosaur ate in a certain spot sixty million years ago is a matter of fact that we are incapable of observing. The same can be said of whether Charlemagne had an even or odd number of hairs on his head, or whether a man in New Zealand stubbed his toe last week. Should we conclude that questions concerning these subjects are literally not truth-apt? — Tarrasque

According to current physics, that information does still exist in the universe, and so in principle those things are empirically verifiable, it's just ridiculously impractical to go about doing that verification. Although some of that information may actually be in principle inaccessible now, just like the position of a particle with well-defined momentum is, in which case yes, those facts about the past are actually undefined, just like most facts about the future. (As part of my views on the nature of time and on modal realism, I fully embrace that there are multiple possible pasts of any given present; pasts just rapidly converge to extremely similar states of affairs, opposite how futures rapidly diverge).

Some people consider verificationism self-defeating. The claim "empirical verification is the only way to learn truths about the world" is, itself, empirically unverifiable. That means, by your account, that someone asking "Is empirical verification the only way to learn true things?" is asking an unintelligible question. The statement itself cannot be true or false. — Tarrasque

This is why I only embrace verificationism explicitly within the narrow domain of descriptive truths. The principle of verificationism itself is not a description of the way the world is, but is something we settle on prior to even engaging in description. Much like the principle of objectivity, and its relation to causation, detailed above.

How can you establish that holding true beliefs is always morally better for us? I can't imagine such a stance being grounded in the "appetites," which you tout as the foundation for moral imperatives. A man being cheated on by his wife experiences no harm, so long as he remains unaware. Discovering the affair is what causes him hedonic harm. Here, one benefits from holding a false belief. Yet, we still believe it is morally wrong to cheat when your partner doesn't know about it. — Tarrasque

The information about the cheating still exists out there in the world threatening the harm of its knowledge to the man. If it were possible (which it's not) to change the world such that all information about the cheating was completely eradicated, then that would be equivalent to changing the world to be one in which the cheating had never happened. And that would be a good thing, if you could literally undo past harms. But we can't, and knowing about them can be prudentially useful in preventing future ones.

Consider believing in a benevolent, all-knowing god. It is plausible that I could live a life where I purely benefit from having this belief. When my life goes poorly, I can keep my chin up, believing that it's all a necessary part of god's great design. When my life goes well, I can attribute my good fortune to god looking after me, rewarding me for my virtue and compensating me for my hardships. This belief may be prudential(thus moral) for me to have, and for others to encourage me to have. Concluding otherwise requires an account of why truth is valuable separate from moral good. — Tarrasque

Such a person holding such a false belief may end up expecting the world to be different from the way it actually is, and so behave imprudentially because of that. (I have relatives with this exact problem, people who could act to make their lives materially better, but who use "God will take care of it" as an excuse to do nothing, and end up suffering for it). If it were the case that such a person could never encounter anything about the world that would be counter to this belief, then that belief would either actually be true, or just be empty. Nominally "believing" nothingness that makes you feel good is morally good, and factually not even wrong, so epistemically permissible, if inconsequential.

If you are concerned with pragmatism rather than existential truth, it would seem most pragmatic to simply postulate abstract objects exist and move on from there. From the pragmatist perspective, who cares if they are real? They are useful. Their explanatory power, and the lack thereof of the alternatives, speaks for itself. — Tarrasque

If you mean abstract moral objects specifically, then what explanatory power do they have? They don't have any impact on how I should expect the world to seem, descriptively, to my senses, to be, so there's no use in positing them as descriptively real objects.

As for the usefulness of abstract objects in general, I do grant them a kind of abstract existence, just like I grant other possible worlds, because doing so helps to explain "why is this world like this?" That doesn't go against my empirical realist (physicalist phenomenalist) ontology, because I'm not a Platonist about them, but rather a mathematicist like Tegmark, but explaining that ontology is a long topic that I'm already planning for another thread. -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerI don’t think wealth can necessarily concentrate in the hands of a few because wealth is not a zero sum game. For instance when I make a dollar you do not lose a dollar, my gain is not your loss. So I cannot agree with that assessment of capitalism. — NOS4A2

I don't necessarily have to lose a dollar for you to gain a dollar, but it is still possible that you can gain a dollar at my expense.

And if everything was truly voluntary and uncoerced, surely people would only go in for trades where each side gains something, so you wouldn't end up with some people getting richer and richer while others get (or stay) poor. The rising tide would float all boats.

If you think that everyone is getting richer together, well then you're just factually wrong, and I'll let others deal with that because it's not worth my time to argue about well-known and easily-googled facts. -

Antinatalism and ExtinctionOk, I can accept that supererogatory acts exist, but I don't believe that conceiving a child could be one, as it is not to anyone's benefit. — JacobPhilosophy

It could be to the resultant child's benefit, if that child's life is on the whole more enjoyment than suffering, or brings about more enjoyment than suffering.

Basically, imagine two worlds, one completely devoid of life, and one of them teeming with the most blissful amazingly enjoyable lives imaginable. Which is better? I think clearly the second. That doesn't make failure to realize the second wrong, because nobody is suffering for the absence of it, but there is more enjoyment happening in the second than in the first.

Of course, you could also imagine two worlds, one completely devoid of life, and one of them filled with unending misery and suffering beyond compare. Which is better? I think clearly the first.

So it's uncertain whether creating life will be on the whole better or worse, which is a large part of why it's supererogatory, not obligatory. (Even giving to charity is like that: in some circumstances it would be better overall if a particular person didn't give to charity, because the suffering they would incur would be worse than the good their donation could do). But it's conceivable (no pun intended) that it might be better. If it weren't, then it would not only be supererogatory, but impermissible; if creating life was guaranteed to make things worse, then creating life should be outright prohibited. -

Antinatalism and Extinctionit seems indifferent to me to consider something "good" if refraining from doing so isn't bad. — JacobPhilosophy

The classic example of a supererogatory good is donating to charity. On most accounts, it is not morally obligatory to do so, it’s not wrong to refrain from doing so, it is permissible to refrain from doing so; but it’s still good to do so. It’s totally okay if you don’t, but it’s still better if you do. -

Is the universe an equation?Balances, equalities, symmetries, are some of the most fundamental parts of modern theories of physics. Symmetries are identical to conserved quantities—Google “Noether’s theorem” for more about that.

That has nothing to do with finitude though. The universe very well could be infinite, so far as we can tell, and math is perfectly capable of handling infinities when it needs to.

There necessarily is some perfect mathematical description of the universe, because otherwise the universe would just be indescribable at all, since we can invent new math as needed to describe it.

That has nothing to do with determinism though, because math is more than capable of handling randomness too.

But just because there is some math full of symmetries and conserved quantities that would perfectly describe the universe even if it is infinite and full of randomness, that doesn’t mean that we can ever be certain that we have figured out which mathematical formula that is. We can’t ever be completely certain. But we can always get arbitrary closer, for as long as we want, approaching that unreachable limit... like in calculus. You know, math. -

Is space/vacuum a substance?Any solid object is mostly space - as you say. And yet any empty space is also "substantial" in having a temperature, a gravity field - the various other measures that suggest the presence of material properties. — apokrisis

As I wrote in a paper a decade and a half ago, “All is but space, and none of it empty.” -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerWe should note that “Capitalism” was initially a snarl word used by socialists to disparage a sort of bogeyman. So I think a name change would be appropriate. — NOS4A2

If the idea you’re talking about is just non-coercive

trade, that already has a name: a free market. Which isn’t the same thing as capitalism. If you’re not in favor of wealth concentrating in the hands of fewer and fewer people, then you’re against capitalism (even if you’re still in favor of a free market), and shouldn’t mind that word being snarled at that bad thing you’re against.

With those concepts separate then maybe you can brainstorm some ideas on how to keep wealth from concentrating like that without sacrificing the free market. And libertarian socialists around the world

will join you in that. -

Antinatalism and ExtinctionPremise 1 must be true, 'else one is morally obliged to give birth. — JacobPhilosophy

There’s a difference between obligatory and supererogatory goods. It can be a good thing to bring people into existence, without it being obligatory, i.e. without it being impermissible to do otherwise.

So while voluntary human extinction may be morally permissible, it may still on the whole be bad, and continuing sapient life still good, if only a supererogatory good. -

Everything is freeI would argue that is an observation and not a rule. There isn't anyenforceable factor at play. — GTTRPNK

There are descriptive as well as prescriptive rules, such as the laws of nature. -

Is there inherent intelligence in probability?Bear in mind that this phenomenon only works when people are at least slightly more likes to be right than wrong.

If the opposite is true, then bigger crowds will give wronger answers. -

New philosophy readerKeep in mind that if you do want to read the original texts, a lot of the older philosophers can be read for free online, so no need to buy books of them unless you really want the paper on your shelf.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is also a surprisingly in-depth free online secondary source where you could learn a lot for free. -

What is this school of ethics called?a school of ethics that was somewhat like utilitarianism but instead of favouirng the maximum pleasure it attempted to favour the most just — Bert Newton

Possibly you are thinking of rule utilitarianism? Though that doesn’t seem a perfect fit.

In any case, your approach to morality sounds a lot like mine, and there’ve been a couple of recent threads that went into that in some depth, with others still to come in the future. The recent ones were:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/8626/the-principles-of-commensurablism

and

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/8749/meta-ethics-and-philosophy-of-language -

New philosophy readerThe key philosophers I’d recommend reading about to get a kind of big picture overview of the whole of philosophy and its history would be Socrates, Aquinas, and Kant.

But it’s often better to read ABOUT them, in secondary sources, rather than trying to read those philosophers themselves. Although the Socratic dialogues are pretty easy so you may as well do those.

Branching out from there, the next key players would be Plato and Aristotle, then Descartes and Locke, then probably Hegel and Russell. Each of those pairs will give you kind of an overview of the main “sides” of philosophy in their respective eras. -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerIt'd be true even if I wasn't.

Statism-libertarianism and capitalism-socialism are nominally orthogonal axes, and if they do correlate, it's along the lines of libertarian socialism (the original left, the original kind of libertarianism and the original kind of socialism) vs state capitalism (the original right). -

Majoring in philosophy, tips, advice from seasoned professionals /undergrad/grad/I have a lot of free time to go for PHD in Philosophy, but I love creative writing. With my creative writing I get a lot of pleasure and some fame, but no money — Eros1982

It probably won't bring you more money, but you could combine creative writing with philosophy and write a kind of philosophical "dialogue" like the ancient Greeks did, but intermixed with more modern narrative conventions, as a way of teaching/popularizing philosophical thinking.

I intended to do that once and started outlining it before realizing I have much more difficulty writing narrative and dialogue than I do essays, so I just turned that project into a series of essays instead. -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerIf some capital is 10x as productive as some other capital, is the former controlled 10x more by the state? — Kev

Who said anything about the state?

Socialism isn't all state socialism. -

What are your positions on the arguments for God?Has he/she done this is other threads and in past engagements? Is he/she a troll that shouldn't be feed or is he/she merely a person with rather difficult social skills. — substantivalism

Recently (past week or two?) they've been doing this to me and 180 Proof in at least two or three threads here. I haven't had any noted problem with them before that. Maybe just having a hard time with the COVID and all. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageAs you are evidently a meticulous thinker, I will have to try my best to act as one in turn. The level of detail in your posts will delay my responses. — Tarrasque

Thank you! And no worries at all about delay. Finding time to do anything on my own (i.e. not hanging out with gf who is locked down with me) is increasingly difficult for me these days myself.

By your account, an "impression" is a speech-act that is world-to-mind, and an "expression" is a speech-act that is mind-to-world. — Tarrasque

Nope! Two different orthogonal divides, the distinction between which is critical to my account. Direction of fit is about the kind of opinion (descriptive or prescriptive), and impression vs expression is about what you’re doing with that opinion relative to someone else (just showing them what opinion is in your mind, or trying to change the opinion in their mind). You can impress or express either kind of opinion, descriptive or prescriptive. If anything, expression is more description-like because it merely shows what your opinions are (so is like describing your opinions), while impression is more prescription-like because it tells someone to have certain opinions (so is like prescribing your opinions). But they are still orthogonal: you can express your beliefs, impress your beliefs, express your intentions, or impress your intentions.

It is when we begin to explore the "correct/incorrect" and "true/false" distinction that I lose your train of thought. I'd like to refer back to something else you said about the importance of direction of fit: "it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match."

I'd also like to borrow a quote from Wittgenstein: "The world is all that is the case." What I take it to mean is that, essentially, if one knew the conjunct of all true propositions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of reality. What it means for something to be true is that it is the case, and what it means for something to be false is that it is not the case. As you correspond "true/false" to descriptivism, I imagine you're inclined to agree. I expect that you might respond with a mirror image of this sentiment, perhaps something like "If one knew the conjunct of all correct intentions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of what-ought-to-be. What it means for something to be "correct" is that it ought to be the case, and what it means for something to be incorrect is that it ought not to be the case." — Tarrasque

Very nearly! If true/false are being used in the narrower descriptive sense then I agree with Wittgenstein there. “Correct/incorrect” I use as broader terms that don’t have that descriptive connotation, so they can apply to either beliefs or intentions. A correct belief is a true belief. And a correct intention is a good intention. (In looser language that e.g. a Kantian might use, what I call a “good intention” would be called a “true moral belief”: a correct cognitive opinion with world-to-mind fit). The conjunct of all correct (good) intentions would be a complete account of morality, in the sense of what-ought-to-be. And what it means for something to be “good” is that it ought to be the case, and “bad” vice versa.

With that in mind, let's hop back to your quote. We have a picture. We wish to judge whether this picture is in error. If the picture is mind-to-world, it is of the usual descriptive sort. It is attempting to depict something factual. Note that, as described, this is strictly a two-way interaction between mind and world. In judging the picture as erroneous, we note that the idea is divergent from the content of the world. But what if the picture is world-to-mind? Now, it is of a prescriptive sort. We would expect that, given the symmetry yet distinction between these two types of claims, we would proceed through inverting the judgement used in the descriptive case. We would judge the world as erroneous for diverging from the content of the picture. I believe you say as much when you establish that the descriptive-prescriptive divide dictates "whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match." Again, this is a strictly two-way interaction between mind and world. What if we apply this to moral judgement?

Instead of a picture of what ought to be, we are now dealing with a claim of it: "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" This is a world-to-mind judgement. Therefore, if the world does not match the mind(I imagine that in this case, that would look like "Russia is not in fact launching nukes"), we judge the world to be in error. This, on its own, entails relativist conclusions. This presents a problem. I expect that you would respond to this problem by claiming that "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" is an intention uttered in error, since it ought not to be the case that Russia launches nukes. At this point, mind-to-world can no longer be considered symmetrical to world-to-mind. Instead of the two-way relation between world and mind that we explicitly find in the mind-to-world case, we are forced to introduce some further arbitration to account for the fact that even in a world-to-mind judgement, the mind can be mistaken in some further way besides simply not matching the world. As opposed to mind-world, we have something like world-mind-standard. You might accept this asymmetry, but it harms the parsimony of your theory to do so. Of course, I would avoid this issue by wholeheartedly accepting that moral states of affairs exist, and utterances concerning them are beliefs which can be true or false in the regular way. — Tarrasque

I must admit I have noted this apparent asymmetry before and struggled to reckon with it. It makes me feel like there is something I haven't fully developed right. When it comes to my approaches to assessing the correctness of either beliefs or intentions, I do end up with a nice symmetry again, but it feels like some bridge between the symmetry of meanings and the symmetry of assessment is missing, for the reasons you state. So I'm glad we're talking about it, because this is the kind of situation where I usually come up with newer, better thoughts.

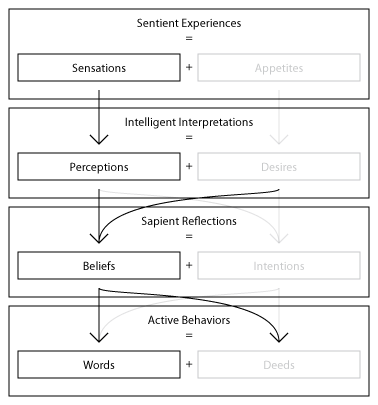

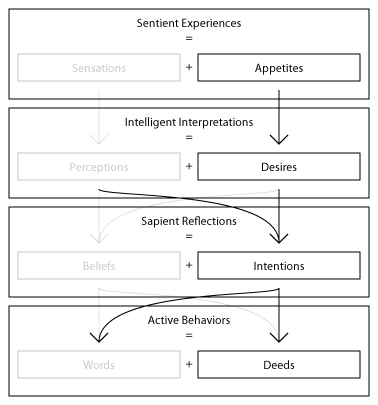

The symmetry I end up with for assessing the correctness of either kind of opinion is checking the opinion against experiences, where experiences come in different varieties that carry their own direction of fit: experiences with mind-to-world fit are sensations (like sight and sound), and experiences with world-to-mind fit are appetites (like pain and hunger). In both cases, assessment of the objective correctness of an opinion needs to account for not just the experiences you are actually having right here and now, but all the experiences anyone could have in any context.

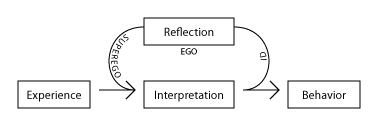

I think perhaps the missing bridge that avoids the asymmetry you note -- and this is just me thinking on the fly here, not recounting thoughts I've already had before, so thank you again for prompting some new thought -- is that direction of fit needs to be reckoned not so much as a relationship between the mind and the world, as it usually is, but rather as a relationship of these different descriptive and prescriptive models to our overall function from our experiences to our behavior. We don't have direct access to the world, all we have is the experience of our interactions with the world, what it does to us and what we do to it.

Being interactions between ourselves and the world, our experiences of either kind are about both ourselves and the world: sensations tell us about how things look to beings like us in certain circumstances, appetites tell us about how things feel to beings like us in certain circumstances. The direction of fit is more between those self-regarding and world-regarding aspects of the experience, internal to the experience, than between the mind and the world itself.

To most beings, the "is" and "ought" aspects of experience are completely intermixed: the world does something to it and that immediately prompts it to do something in response. Sentient beings, on the other hand, differentiate our experiences into those to be used to build a "still life" (mind-to-world-fit picture), our sensations, and those used to build a "blueprint" (world-to-mind-fit picture), our appetites. Sapient beings, furthermore, reflect upon those pictures and assess whether they have correctly constructed them.

We then behave in such a way as to bridge the difference between the two images we've constructed: to change things from the "still life" (mind-to-world image) to the "blueprint" (world-to-mind image). The two images can thus be defined in terms of their role in driving our behavior: one is the "from" side of the change we're making, and the other is the "to" side.

This doesn't fall into relativism because in principle both of those images can be constructed in an objective manner, taking into account not just the experiences you are actually having right here and now, but all the experiences anyone could have in any context.

P2. If stealing is wrong, then cheating on a significant other is wrong — Tarrasque

This doesn't seem to be a logically necessary premise in the same was as "if stealing is wrong, getting your little brother to steal is wrong". So it makes sense that you wouldn't reconstruct that in the same way as the brother implication, as "(stealing) implies (cheating)", because that's incorrect; there could be stealing and not cheating. (BTW I think you reversed those a couple times in your post, not that it makes a big difference). Your reconstruction as -- to use my shorter nomenclature from earlier -- "be(not(stealing)) implies be(not(cheating))" is thus a better reconstruction than "steaming implies cheating". But that is then a questionable premise because it's not a logical necessity, as you're just saying:

be(not(cheating)) or not(be(not(stealing)))

or equivalently:

not(be(not(stealing)) and not(be(not(cheating))))

because material implication is counterintuitive like that, unlike logical implication.

(I saw your chart, but that raised more questions than it answered. Why is "bad" contained within "supererogatory?") — Tarrasque

For the same reason that "false" is contained within "contingent": supererogatory = not-obligatory, and all bad things are not-obligatory, just like contingent = not-necessary, and all false things are not-necessary. (There are some things that are necessarily false, but that just means impossible; likewise, things that are "obligatorily bad", so bad you are obliged not to do them, are just impermissible).

But yet, everybody's senses in all circumstances could still lead to something false. There might be things which are true of the world and yet empirically unverifiable, even in principle, like the existence of a god. — Tarrasque

I disagree. When it comes to the limited domain of descriptive propositions, I agree completely with the verificationist theory of truth: a claim that something is true of the world yet has absolutely no empirical import is literally meaningless nonsense. If something like gods can really be said to exist, there must be something observable about them.

Woah, woah. Descriptive statements are pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things are? That itself is prescriptive! — Tarrasque

This mostly boils down to the difference between impression/expression and prescription/description clarified at the start of this post. That "should" there is more an "impressive should" than a "prescriptive should"; natural language can be sloppy, again.

But in response to both this and the large part about the normativity of reasons generally that I didn't quote earlier, I now remember that I have in other contexts thought about normativity as it relates to thought more generally, not just about prescriptive thoughts like intentions, in my work on philosophy of mind and will.

Basically, the reflexive process of self-judgement involved in forming "thoughts" (beliefs and intentions) involves casting both our descriptive and prescriptive judgements upon either our descriptive or our prescriptive judgements. When we (descriptively) look at what we perceive (descriptively) and judge (prescriptively) that it is the correct thing to perceive, that constitutes a (descriptive) belief. When we (descriptively) look at what we desire (prescriptively) and judge (prescriptively) that it is the correct thing to desire, that constitutes a (prescriptive) intention.

So you're right, there is normativity/prescriptivity involved in reasoning generally, that I was forgetting about earlier.

The prescriptivity involved there is still ultimately the same kind as moral prescriptivity, though. It's basically a case of considering what the proper function of a human mind is -- proper as in good, good as in prudential good, which we've already established boils down to moral good -- and then looking upon yourself in the third person, so to speak, and thinking "Hey, there's a mind! Is it functioning properly? No no, it should be perceiving like this and desiring like that instead..." It's self-parenting. Parents teach their kids how to think, both in terms of figuring out what is true and in terms of figuring out what is good, for the moral good of those kids, and everyone they'll have an impact on, right? Likewise, making sure we ourselves are thinking correctly is ultimately for a moral good too.

I also think it's inaccurate. Consider a color judgement. I have a degree of red-green colorblindness. If I make a descriptive claim such as "this chair is brown," I would sure hope I'm not implying that everybody else ought to see the chair the way I do! I am merely reporting how I observe the chair to be. — Tarrasque

That would be an expression, not an impression, as clarified at the start of this post.

Thank you for this engaging conversation! No rush on your response, it'll take me a while to get to it anyway. -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerI think you misread: I didn't mean "capital distribution" as in the act of distributing capital, but rather the state of affairs regarding who has what capital. "where capital distribution is at most a negligible factor" means that how much capital people have doesn't significantly differ, or else doesn't make a significant difference (i.e. lacking capital doesn't impose costs, having capital isn't a source of profit).

Capital is a kind of property, in any case, and the only kind that really matters for macroeconomic purposes. Nobody cares about the distribution of toothbrushes or toys. It's the distribution of the things needed to live and work -- that's what capital is -- that matters. The distribution of the rest of it can sort itself out easily enough so long as everyone has access to the things they need to live and work. -

What are your positions on the arguments for God?Pointing out someone else’s poor discourse is not an ad hominem.

Why do I even bother replying, everyone else can see how pointless this is and I’m sure as heck not going to get through to you. -

The dirty secret of capitalism -- and a new way forward | Nick HanauerWhen you remove the floating abstractions (namely the concept of capital) it's pretty hard to argue against capitalism. — Kev

If you get rid of the consideration of capital, then you’re not even talking about capitalism anymore, but (probably) just about a free market, which is not the same thing. A free market where capital distribution is at most a negligible factor is market socialism, which is decidedly not capitalist. -

What are your positions on the arguments for God?Should I take your inability or unwillingness to answer the metaphysical questions (the nature of your existence) as acquiescence by silence? — 3017amen

No, and as I already said, it’s arguing in bad faith to even suggest that you might. That’s not how reasoned discourse works, and your petty schoolyard attempts at shaming others into engagement won’t work here. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageBut it is of course a nonsense claim. As I said, the proposition is absurd. You may as well ask me what it would mean for morality to be made of cheese. I assume the religious answer would involve souls and divine plans somehow. — Kenosha Kid

The thing is, other than gods not existing, it seems no less absurd to me than your claims about what is “the phenomena underlying our morality”. It’s that “underlying” relationship that seems vague and unclear to me. I get the descriptive explanation of why we have certain moral intuitions, that’s perfectly clear and uncontested. What I don’t get is how you get from us having those intuitions to any manner of evaluating moral claim, UNLESS it’s simply that any way anyone is inclined to morally evaluate anything is correct simply by virtue of them being inclined to evaluate it that way.

So... if there were gods, and they did something that made us inclined to evaluate things certain ways, would that then make them the phenomena underlying our morality? Or, if they didn’t actually MAKE us inclined, but just gave orders and offered rewards and punishment, would that be enough?

- is 'the cold-blooded murder of ginger people is good' true? What moral reference frame can that possibly be true in? None. — Kenosha Kid

The Nazis though the cold blooded murder of lots of different groups was good. “Ethnic cleansing” in general is seem as good by the people who do it, hence the superlative “cleansing”. I would not at all be surprised if some society had or would support the murder of all gingers.

What makes them wrong? Or more on topic, what does it mean to say they are wrong, or that they are right?

If your meta-ethics isn’t capable of handling the true claim that Hitler did something wrong (even though he and his society thought it was right), then that looks like a pretty serious problem. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageYou shut down conversation about the actual issue — Isaac

I shut down an attention-sucking tangent. Now this is becoming another and I would like to shut it down so that more productive conversation can take place instead.

You are free to completely ignore me if you don't like the way I discuss things, I routinely ignore some people here for exactly that reason, we're not here out of duty, it's supposed to be interesting, not drudgery. — Isaac