Comments

-

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageFirst, I want to commend you for the substantial time and effort you have clearly put into philosophizing. You have managed to put something together which is, on the whole, innovative, and impressive. As to whether or not it does the best job among competing theories by metrics of truth and explanatory power, I hold my reservations. But, I expect a good time investigating it. — Tarrasque

Thanks! I'm looking forward to this conversation too (and enjoying it so far already).

"John believes that abortion is impermissible, while I believe abortion is permissible." This is a statement which makes sense, and would not be strange to hear. In a sentence such as this, do you hold that the use of the word "believes" is a category error? If moral utterances do not express beliefs, how can the above be true or false? Must it be false? How would you reform this sentence to preserve its meaning? — Tarrasque

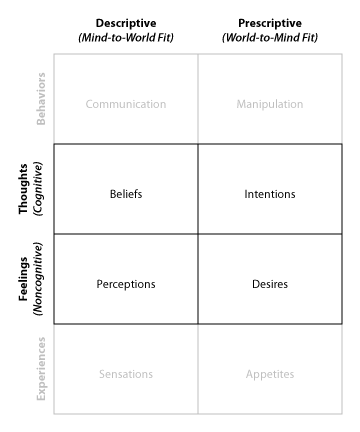

Natural language is inherently sloppy, and I don't set out to admonish anyone for casually using "belief" to refer to their moral opinions. But because "belief" has descriptivist connotations, especially in the Kantian vs Humean context, I try to be careful to avoid it myself. I say instead that moral utterances impress (and so implicitly also express; you caught the part about impression vs expression earlier?) intentions. And I say that intentions can be objectively correct or incorrect ("true" and "false" also frequently have descriptivist connotations, so I try to avoid them myself, but recognize their casual use). Both intentions and beliefs are subsets of what I call "thoughts" (as distinct from "feelings", "experiences", and other mental states), so the simplest rephrasing of the above would just be to say "John thinks ... while I think ..." instead, since the permissible/impermissible already carry subtler imperative force.

(I want to launch into the next thing I wanted to bring up, thoughts vs feelings or "order of opinion" here, but I don't want to break the flow of this response so I'll put that at the bottom instead).

In general, when not dealing with modalities like that, I would most strictly phrase things as "so-and-so believes such-and-such (to be the case)" for descriptions and "so-and-so intends such-and-such (to be the case)" for prescriptions.

Furthermore, atomic moral sentences can be used to construct valid arguments. Example,

P1. Stealing is wrong.

P2. If stealing is wrong, then getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

C. Getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

If moral statements express beliefs about matters of fact, this is no different from a common variety modus ponens. Otherwise, there is something strange going on here. If I understand you correctly, when I utter "stealing is wrong," I am impressing on my audience some imperative not to steal. This normative evaluation is capable of being correct or incorrect, by your account, but the meaning of the sentence is nonetheless to impress a particular intent. With this in mind, let us semantically dissect the above modus ponens.

In P1, the atomic sentence "stealing is wrong" impresses an intent by its very utterance. This is due to the type of speech-act you claim it is. In a sense, the statement "stealing is wrong" cannot be disentangled from this force of impression.

Yet, in P2, I state that "IF stealing is wrong," then this other thing is wrong. In this case, I am not committing to impress anything on my audience. The meaning of "stealing is wrong" as an atomic sentence appears different than its use as the antecedent of a conditional. This is problematic for the validity of moral modus ponens. Your theory will have to account for this in some way to be successful. — Tarrasque

This is why I brought up the "Socrates being mortal" example before.

In my system of logic, I propose that rather than treating a statement like "All men are mortal" as one proposition and a statement like "All men ought to be mortal" as another, completely unrelated proposition, we instead take the idea that they have in common, "all men being mortal", and wrap that in a function that conveys what we wish to communicate about some attitude toward that idea. For example we might write there-is(all men being mortal) to mean "all men are mortal", and be-there(all men being mortal) to mean "all men ought to be mortal"; and generally, write there-is(S) and be-there(S) for the equivalent descriptive and prescriptive statements about the idea of some state of affairs S, whatever S is. We might wish to use shorter names for the functions, like simply is() and be(), or some other names entirely; I am merely using the indicative and imperative moods of the copula verb "to be" to capture the descriptive and prescriptive natures of the respective functions.

So in your modus ponens, the logical relationship is actually between "stealing happening" and "getting your little brother to steal": getting your little brother to steal entails stealing happening. So if it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening)), and (getting your little brother to steal) entails (stealing happening), then it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(getting your little brother to steal)).

You can replace it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is with it-is-the-case-that-that-there-is and you get the same logical relations, just with descriptive force instead of prescriptive force.

Alright, I'm following so far. Whether or not this conception is accurate, I like it a lot. — Tarrasque

Thanks again!

To this point, I will simply offer an alternative explanation. I don't think that "same idea, two different attitudes toward it" captures what is going on in this case. Rather, I hold that these are two distinct ideas. One is that people do murder, the other is that people ought to murder. Somebody could agree or disagree(correctly or incorrectly) with either, in any combination. In accordance with the is-ought distinction, my agreement with one cannot logically follow merely from my agreement from the other. — Tarrasque

I agree completely, and I didn't mean to suggest otherwise. My point is just that the opinion "people do murder" and the opinion "people ought to murder" can both be decomposed into some attitude or another toward the idea of people murdering: one descriptive attitude (the idea does happen) and one prescriptive attitude (the idea should happen). You can totally have different views on each of those full opinions: agree that it does happen, disagree that it should happen. That was the point of using that example, that for most people, I expect their agreement on opinions about the same idea (people murdering) will be opposite for those two kinds of attitude: they'll agree that it does, disagree that it should. Thus illustrating what "people do murder" and "people ought to murder" have in common (the idea of people murdering), and different (the attitudes toward that idea).

I was thinking of supererogatory action when I typed that out, so I'm glad you caught it. While you are correct that "he is obligated to X" is much normatively weightier than "he ought to X," I still think that using "ought" to refer to supererogatory acts is a butchery of our use of the word. If you were to tell me "everybody on the planet ought to live life in constant ecstasy" or "you ought to sacrifice your life to save mine," I would strongly disagree with you. If you then told me that when you used "ought," you really just meant that these things would be good, I would come to agree with you, still believing that you had originally misused the word "ought." I will provide more reasons why I think this below. — Tarrasque

I see this as just another example of natural language being sloppy. I agree that in some cases "ought" will carry connotations of obligation, rather than merely supererogatory good, and that being blithe to those differences will result in miscommunication. But that's something to sort out rhetorically, and doesn't have much to do with the actual underlying logic I'm on about here.

Alright, this is the place where I want to talk about reasons and rationality. In all your theorizing on normativity thus far, I have only seen you touch on moral normativity. This is not the only type. I can make claims like:

"You should stop smoking."(Prudential ought)

"You ought to proportion your belief to the evidence."(Rational ought)

"You ought not to beat your wife."(Moral ought)

"You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do."

I would like to touch on that last example a little more. "You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do." If you are anything like me, you find that incredibly intuitive. I have come to believe that it is essentially the definition of ought. The thing that a person ought to do is the thing that they have the most reason to do. Moral reasons are a type of reason, but often the thing that we have the most moral reason to do is not the thing that we have the most total reason to do(ergo supererogatory actions).

Since moral oughts are not the only type of oughts we use, I am surprised to not see theorizing on broader normativity in your work. Questions like "Is X rational" or "Is P a good reason to Q" need to be answerable, or at least explainable, by any plausible theory of normativity. — Tarrasque

I see prudential oughts as boiling down to a kind of moral ought. Taking care of yourself is a kind of moral good -- not necessarily an obligatory one, but still a moral one even if only supererogatory, you matter just like everybody else matters -- and instrumentally seeing to moral ends is still a kind of moral good. So you should stop smoking because if you don't you'll probably suffer and die, and people suffering and dying is bad.

Rational "oughts" I think can be better rephrased descriptively. "If you proportion your belief to the evidence your belief is more likely to be accurate." You might ask "but should beliefs be accurate?" and the answer to that is a trivial yes, because believing something just is thinking it's an accurate description of reality. If you didn't care to have an accurate description of reality, you wouldn't bother forming beliefs.

I agree completely that "you ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do" is incredibly intuitive, but I think that a reason to do something just is a moral imperative; largely because of how prudential self-care collapses to moral normativity on my account.

I do have a lot more thoughts on how to justify both beliefs and intentions, which I think is more of the rationality-normativity you're thinking of. But that would get way outside the scope of this thread on semantics. I do intend to start threads on them later, and I hope you'll join in then.

In the meantime, here's the bit about order of opinion (thoughts vs feelings) I cut out from above for flow:

The difference in attitude alone isn't enough to account for what I mean by "intention" as distinct from "desire", which both have the same direction of fit, world-to-mind. To explain that, I need to first elaborate on differences in attitude between opinions with the same mind-to-world fit. More fundamental than opinions are experiences, and an experiences with mind-to-world fit are called "sensations". These are the raw input from our senses, free from any interpretation: the contents of a sensation are colors of light, pitches of sound, and so on, not yet shapes or words. In contrast, the simplest opinions with mind-to-world fit, first-order or irreflexive opinions of that type, are called "perceptions". These are interpretations of that raw sense-data into more abstract representations, but still of the same idea. (An analogy can be made here between raster and vector computer graphics formats, where a raster format stores an array of colored pixels and any shapes that appear in them are merely inferred by human viewers out of the patterns in those pixels; while a vector format stores abstract representations of exact shapes directly, which can then be rendered as arrays of pixels for display. The human viewer senses something like the array of pixels with their eyes, but then in perceiving shapes in the image, they are essentially "vectorizing" the image in their own mind). Further still, higher-order or reflexive opinions with mind-to-world fit are called "beliefs", and I hold that the distinguishing feature of beliefs is that they "objectify" what have thus far been completely subjective opinions, because they are reflexive in attitude, being capable of casting judgement on other opinions with the same content: one can disbelieve one's perceptions, or judge someone else's perception to be wrong as well. A belief is a perception that has been questioned (however thoroughly) and found (however correctly) to be the correct interpretation of sensations, the correct picture to use as a representation of the world, the correct opinion with mind-to-world fit.

I hold that there are analogues to all of those, but with world-to-mind fit instead. I call experiences with world-to-mind fit "appetites". These are composed of the raw inputs of things like pain, hunger, thirst, and so on. While sensations are the experiences that make us feel, on a raw unexamined level, like the world is some way, appetites are those experiences that make us feel, on a raw unexamined level, like the world ought to be some way. I visualize this as building two images, two ideas, in our minds: one of them a picture of the world as it is, meant to serve as a representation of the world, meant to fit the world; and the other of them a picture of the world as it ought to be, meant to serve as a guide for the world, meant for the world to fit. Sensations are those experiences that feed into that first picture, and appetites are those experiences that feed into that second picture. In contrast to those uninterpreted appetites, the simplest opinions with world-to-mind fit, first-order or irreflexive opinions of that type, are called "desires", like the expressivists and Humeans are all about, which I hold to differ from appetites in the same way that perceptions differ from sensations: desires are interpretations of appetites, and while an appetite may have as its content the feeling of, for example, hunger pains, the desire that is interpreted from that will have as its content instead, for example, to eat a burrito; just as sensations may contain patterns of light while perceptions instead contain shapes. And lastly, higher-order or reflexive opinions with world-to-mind fit I call "intentions", and I hold that the distinguishing feature of intentions is that they "objectify" what have thus far been completely subjective opinions, because they are reflexive in attitude, being capable of casting judgement on other opinions with the same content: one can intend other than what one desires, or judge someone else's desires to be wrong as well. An intention is a desire that has been questioned (however thoroughly) and found (however correctly) to be the correct interpretation of appetites, the correct picture to use as a guide for the world, the correct opinion with world-to-mind fit.

It is that reflexivity of attitude that I hold to make an opinion cognitive, apt for being found objectively correct or not, though as they differ in the purposes to which they put their ideas, they differ in the criteria by which they are to be judged correct or incorrect: beliefs are to be judged by appeal to the senses, everyone's senses in all circumstances if they are to be judged objectively, and intentions are to be judged by appeal to the appetites, everyone's appetites in all circumstances if they are to be judged objectively. Intentions are cognitive but non-descriptive opinions; in the same way that perceptions are descriptive but non-cognitive opinions. I like to term cognitive opinions like beliefs and intentions "thoughts", and non-cognitive ones like perceptions and desires "feelings". So when I say that I hold prescriptive statements, moral utterances, to impress intentions rather than to express desires, I mean that they are not simply demonstrating the speaker's present feelings about how things ought to be, any more than descriptive statements are simply demonstrating the speaker's present feelings about how things are. They are instead pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things ought to be, in the same way that descriptive statements are pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things are. -

On the existence of God (by request)My position is that the fundamentals can self-exist, because we necessarily have no way of knowing whether the mathematical structure that is identical to our physical universe is dependent on any deeper fundamentally inaccessible structure, so as far as we can tell it does self-exist, and if it can self-exist, there's no reason to suppose that all other mathematical structures don't as well. We can "discover" these other structures by "inventing" them (discovery and invention of ideas being not really different on my account), because our minds, like everything, are necessarily limited by the same logical possibilities as those structures, so something that we can think of is necessarily something that can exist, and if everything that can exist does exist...

-

On the existence of God (by request)The short answer is that numbers aren't the basic elements of math; sets are. Numbers are made of them, as are all other mathematical objects. For the long answer...

First we define a series of sets, starting with the empty set, and then a set that only contains that one empty set, and then a set that only contains those two preceding sets, and then a set that contains only those three preceding sets, and so on, at each step of the series defining the next set as the union of the previous set and a set containing only that previous set. We can then define some set operations (which I won't detail here) that relate those sets in that series to each other in the same way that the arithmetic operations of addition and multiplication relate natural numbers to each other. We could name those sets and those operations however we like, but if we name the series of sets "zero", "one", "two", "three", and so on, and name those operations "addition" and "multiplication", then when we talk about those operations on that series of sets, there is no way to tell if we are just talking about some made-up operations on a made-up series of sets, or if we were talking about actual addition and multiplication on actual natural numbers: all of the same things would be necessarily true in both cases, e.g. doing the set operation we called "addition" on the set we called "two" and another copy of that set called "two" creates the set that we called "four". Because these sets and these operations on them are fundamentally indistinguishable from addition and multiplication on numbers, they are functionally identical: those operations on those sets just are the same thing as addition and multiplication on the natural numbers.

All kinds of mathematical structures, by which I don't just mean a whole lot of different mathematical structures but literally every mathematical structure studied in mathematics today, can be built up out of sets this way. The integers, or whole numbers, can be built out of the natural numbers (which are built out of sets) as equivalence classes (a kind of set) of ordered pairs (a kind of set) of natural numbers, meaning in short that each integer is identical to some set of equivalent sets of two natural numbers in order, those sets of two natural numbers in order that are equal when one is subtracted from the other: the integers are all the things you can get by subtracting one natural number from another. Similarly, the rational numbers can be defined as equivalence classes of ordered pairs of integers in a way that means that the rationals are the things you can get by dividing one integer by another. The real numbers, including irrational numbers like pi and the square root of 2, can be constructed out of sets of rational numbers in a process too complicated to detail here (something called a Dedekind-complete ordered field, where a field is itself a kind of set). The complex numbers, including things like the square root of negative one, can be constructed out of ordered pairs of real numbers; and further hypercomplex numbers, including things called quaternions and octonions, can be built out of larger ordered sets of real numbers, which are built out of complicated sets of rational numbers, which are built out of sets of integers, which are built out of sets of natural numbers, which are built out of sets built out of sets of just the empty set. So from nothing but the empty set, we can build up to all complicated manner of fancy numbers.

But it is not just numbers that can be built out of sets. For example, all manner of geometric objects are also built out of sets as well. All abstract geometric objects can be reduced to sets of abstract geometric points, and a kind of function called a coordinate system maps such sets of points onto sets of numbers in a one-to-one manner, which is hence reversible: a coordinate system can be seen as turning sets of numbers into sets of points as well. For example, the set of real numbers can be mapped onto the usual kind of straight, continuous line considered in elementary geometry, and so the real numbers can be considered to form such a line; similarly, the complex numbers can be considered to form a flat, continuous plane. Different coordinate systems can map different numbers to different points without changing any features of the resulting geometric object, so the points, of which all geometric objects are built, can be considered the equivalence classes (a kind of set) of all the numbers (also made of sets) that any possible coordinate system could map to them. Things like lines and planes are examples of the more general type of object called a space. Spaces can be very different in nature depending on exactly how they are constructed, but a space that locally resembles the usual kind of straight and flat spaces we intuitively speak of (called Euclidian spaces) is an object called a manifold, and such a space that, like the real number line and the complex number plane, is continuous in the way required to do calculus on it, is called a differentiable manifold. Such a differentiable manifold is basically just a slight generalization of the usual kind of flat, continuous space we intuitively think of space as being, and it, as shown, can be built entirely out of sets of sets of ultimately empty sets.

Meanwhile, a special type of set defined such that any two elements in it can be combined through some operation to produce a third element of it, in a way obeying a few rules that I won't detail here, constitutes a mathematical object called a group. A differentiable manifold, being a set, can also be a group, if it follows the rules that define a group, and when it does, that is called a Lie group. Also meanwhile, another special kind of set whose members can be sorted into a two-dimensional array constitutes a mathematical object called a matrix, which can be treated in many ways like a fancy kind of number that can be added, multiplied, etc. A square matrix (one with its dimensions being of equal length) of complex numbers that obeys some other rules that I once again won't detail here is called a unitary matrix. Matrices can be the "numbers" that make up a geometric space, including a differentiable manifold, including a Lie group, and when a Lie group is made of unitary matrices, it constitutes a unitary group. And lastly, a unitary group that obeys another rule I won't bother detailing here is called a special unitary group. This makes a special unitary group essentially a space of the kind we would intuitively expect a space to be like — locally flat-ish, smooth and continuous, etc — but where every point in that space is a particular kind of square matrix of complex numbers, that all obey certain rules under certain operations on them, with different kinds of special unitary groups being made of matrices of different sizes.

That special unitary group is considered by contemporary theories of physics to be the fundamental kind of thing that the most elementary physical objects, quantum fields, are literally made of. Excitations of those quantum fields, which is to say particular states of those special unitary groups, constitute the fundamental particles of physics, which combine to make atoms, molecules, stars, planets, living cells, and organisms, including us. So in a very distant way we can be said to be made of empty sets.

(And as all of the truth functions, and so all the set operations, and all the other functions built out of set operations, can be built out of just joint denial, and the objects they act upon are built up out of empty sets, everything can in a sense be said to be made out of negations of nothing) -

Why aren't more philosophers interested in Entrepreneurship?Seems like you are talking about franchising or simply what banking does. — ssu

Not just that. Anyone who buys buildings and equipment and then pays other people to operate them is letting others use their capital (the stuff) in exchange for money (the difference between what the customer pays and the employee receives).

The only reason the employees would agree to such an arrangement is because they don’t have and can’t afford the stuff they need to do their jobs themselves. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageSo if gods actually existed, would divine command theory be a fine meta-ethics, and the Euthyphro a bad argument, because “is what the gods command actually good?” is asking for “real magic” when the priests are showing you the only “magic“ there actually is, these commands from the gods?

How would that mesh with your bio-social relativism? The body and your society say that one thing is good, the gods (remember we’re imagining a world where they’re real) say another thing is. Which should we listen to? Why? Which is actually good? What should we actually do? Is that a meaningless question?

Even within your bio-social relativism, what if the body and society give different directives? Which should we listen to and why? -

Why aren't more philosophers interested in Entrepreneurship?What I said is an elaboration of the mechanisms behind what Kaarlo said. “Entrepreneurs” in our capitalist world are more often than not just people with capital who want more of it, so they “create businesses” (lend their capital) where those who do the actual work can produce (using the borrowed capital) for those who pay the actual money, and then the “entrepreneurs“ take their cut off the top of that process. Enabling producers to actually produce and fulfill the needs of customers is incidental: they’ll do as little of that as they can get away with, only as much as they have to in order to achieve their goal of multiplying their capital.

-

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageI'm not seeing the difference. If majority agreement does not act as any kind truth-maker then how is it that ideas which have majority support can be taken as a reasonable background assumption? From what consequence of majority agreement does it derive its reasonableness if not some greater liklihood of being right? — Isaac

It’s a discursively thing at issue here, not a strictly logical one. If one were to propose to the pre-Copernican world something that takes for granted that the Earth revolves around the sun, one would first have to get anybody at all on board with that presupposition before one could move on to the actual topic. But that same discussion today doesn’t first have to established heliocentrism: we can take it for granted that most people just assume it and go on from there, and argue for heliocentrism with the doubters elsewhen, but never telling them to just accept it because the majority does.

I suddenly shifted away from debating you when Echarmion’s comment reminded me that I didn’t come here to discuss the merits of heliocentrism, I came to discuss some ideas about space travel that take heliocentrism for granted, and then foolishly got bogged down debating a geocentist instead of getting on with the actual topic.

Listen with some moderate humility to what those others have to say where you've no reason other than your personal disagreement to dismiss them. — Isaac

I have reasons for disagreement, that I’ve repeatedly shared. And I do listen carefully to everyone, looking for anything new I haven’t already considered. There just isn’t a lot of that to be found, so most things I listen to are things I’ve already heard and already have reasons not to agree with. Which I then share. -

Natural and Existential MoralityFundamentalism is not necessarily antisocial. — Kenosha Kid

Social-vs-antisocial is a first-order difference (“what should we do?”). Fundamentalism-vs-science-vs-relativism is a second-order difference (“how do we figure it out?”). Any of the second-order methodologies could in principle reach any of the first-order conclusions.

I do not labour under the impression that you know what the moral objects you believe in are. — Kenosha Kid

I don’t “believe in moral objects” at all, which again makes me think you’re not understanding what my position even if. I don’t believe that there exist somewhere in reality some kind of things that make moral statements true. I just think it’s possible for one moral claim to be more or less correct than another, in a way that doesn’t depend on who or how many people make that claim.

I wonder how familiar you are with the different possibilities in moral semantics, and I invite you to check out my ongoing thread on Meta-ethics and Philosophy of Language where we’re discussing it. It sounds like you think I’m asserting some kind of non-naturalist moral realism in contrast to your moral subjectivism, but both of those are kinds of descriptivism, and I actually advocate a non-descriptivist form of cognitivism.

Seems remarkably similar. — Kenosha Kid

I don’t see it, and if you do I miscommunicated. What you said sounds analogous to two kinds of knowledge, the empirical kind that everyone has and the mystical kind that only initiates to secret orders get. What I meant was supposed to be analogously to a spectrum of different degrees of empiricism, from the ordinary kind everyone uses in their day to day lives to the honed and refined kind that professional scientists use. Scientists aren’t using a different kind of knowing, they’re just better at using the ordinary kind. And my moral methodology isn’t supported to be a different kind of morality, just a better use of the ordinary kind. -

On the existence of God (by request)Even in a computer you can't have abstraction only. You have to go the the shop and buy a substantial computer if you want to compute. — EnPassant

Sure, but that computer is made of stuff that can be described perfectly by more mathematical abstractions... such that the computer itself might be a simulation inside another computer, which itself might be a simulation, inside another computer, that might be a simulation, etc. That’s alternating between getting down to a perfect mathematical description of the thing in question, and then supposing that that structure is implemented atop another structure, of which we can give another perfect abstract description, before supposing that that is implemented atop yet another structure, and so on. Why stop at the “and there’s some other structure this is implemented on top of, no deeper details of which can ever possible be known” step, instead of the “and here is the most perfect abstract description of things, which is not implemented atop any deeper structure” step?

That begs the question; you can grow cabbages on the real territory but not on the map, so there's a difference. — EnPassant

If you can’t do something with the “perfect” map that you can do with the territory, then its not really a perfect map. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageSo no the majority does make right? Your meta-philosophy is very mixed. — Isaac

Majority doesn’t make right, but it shows that this isn’t some crazy new idea of mine that needs to be conclusively proven before we can move on. It’s a reasonable background assumption that can be taken as a premise for another conversation, not something that the entire conversation has to be about.

If what you're discussing here really is new and not something that philosophers before you have already thought of and dismissed, then you need to publish. Do you even realise the monumental unlikelihood of you having come up with some solution that 2000 years of moral philosophers haven't? — Isaac

What do you think is appropriate discussion material for a philosophy forum? Are we only allowed to talk about things that other philosophers have already said? No original thoughts allowed?

I don’t know for sure how original my thoughts are. I’m passingly familiar with a few similar ones. I hope to find out more about any similar thoughts and the arguments about them that have already been had, if any, by discussing them in a public place like this. I don’t have the time = money to conduct an exhaustive professional literature review to be absolutely sure of where my thoughts fit in the ongoing professional dialogue, and I don’t have the accredited nor the time = money to get it to even be considered by a professional publication.

What else is someone who has as far as they can tell original thoughts supposed to do in such a situation, besides talk about them with other amateurs? -

Why aren't more philosophers interested in Entrepreneurship?Jobs are created by people who have needs, and something to trade for the facilitation of those needs.

In a reasonable world, entrepreneurs would create newer more specific jobs to accomplish those “natural jobs” (fulfilling people’s needs), just like engineers create newer more specific tools out of the “natural tools” given by the universe and discovered by science.

I don’t have any problem at all with entrepreneurship in that regard.

The problem that @Kaarlo Tuomi is on about, that you disagreed with, and that I’m now supporting, is that in the actual world more often than not that isn’t how and why entrepreneurship gets done. There are people with needs and people who would be able to fulfill those needs (i.e. to produce) if only they had the means (of such production, i.e. capital) to do so, which they don’t, because almost everyone is poor and struggling even to meet their own needs. Then you’ve got the tiny fraction of people who control all that capital and want to use it to extract more of it so that they can keep paying other people to satisfy their own needs without ever running out.

Those people, to their own ends, thus agree to let the actual producers use (not have, just use, borrow) their capital as a means of production, on the condition that a large part of the money that the people in need (the customers) pay in exchange for that product go to the capital-owner, rather than the people doing the actual production. And those capital-owners just inserting themselves between the producers and customers get called “entrepreneurs” and “job creators”. Which is like calling the Mafia “security guards”, because so long as you pay them they’ll make sure that your shop doesn’t get wrecked, by them. The capital-owners similarly “create jobs” merely by allowing the use of capital so long as you pay them for it, instead of them just hoarding it all to themselves merely as incentive to make people’s pay them to borrow it. -

The hard problem of materialism - multiverseThat is similar to my kind of functionalist panpsychism. On my account, everything has whatever is metaphysically necessary for conscious experience, everything in some trivial sense “has experience”, but what that experience is like depends entirely on the function of the thing, and consciousness proper is a kind of reflective functionality, self-awareness basically, and only things that have that functionality have what we ordinarily mean by “conscious experience”. But it’s not like the emergentist account where when mindless matter arranges just right suddenly a new kind of thing, mind, occurs; rather, the elementary constituents of mind are already present in everything, and fully fledged mind as we usually mean it is built up out of that just like our physical behaviors are built up out of the physical behaviors of the atoms etc we’re made of.

-

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageBrilliant work of philosophical investigation "I'm going to ignore the part where there's some issue with one of my central claims and move on to discuss my conclusions assuming it to be the case" — Isaac

The fact that YOU don’t agree with one point isn’t reason to halt the entire discussion that wasn’t even supposed to be about that point just to waste pages and pages on pointlessly trying to convince YOU of something most people don’t need convincing of.

Moral nihilism or relativism (same thing really) are far, far from universally accepted, and the common objection to numerous of the meta-ethical theories surveyed in the OP is that they require moral nihilism or relativism. The point of this thread is to explore the possibilities a meta-ethics that is not vulnerable to the common objections to all those ones surveyed in the OP. That you are unconvinced by one of those objections shouldn’t stop the whole rest of the discussion.

What even is your meta-ethics anyway? Expressivism? -

The hard problem of materialism - multiversewho decides what's physical, natural and what is not? — Eugen

What's physical or natural is what can be checked against empirical experience.

The supernatural therefore definitionally makes no difference that anybody could possibly tell, so its existence and its non-existence are indistinguishable and therefore identical. -

The hard problem of materialism - multiverseBasically, if when you arrange a bunch of physical stuff, suddenly something metaphysically new starts happening that's not just a sum or aggregate of what the physical stuff was doing, then there's something non-physical that's going on, so you've got physical stuff and non-physical mental stuff both happening, basically a kind of dualism.

The alternatives are that either nothing metaphysically new starts happening then, because there is nothing metaphysically mental going on in anything ever -- eliminative materialism -- or else nothing metaphysically new starts happening then, because everything metaphysically necessary for mind as we know it is already going on everywhere all the time -- panpsychism.

Basically, whatever is metaphysically necessary for minds as we know them either happens for nothing (eliminative materialism), for only some things (dualism, and strong emergentism), or everything (panpsychism). Only the first and last are really compatible with physicalism, the middle ones are not. -

Why aren't more philosophers interested in Entrepreneurship?he wanted to be free and independent in the world instead of being beholden to someone who decides what he gets paid, what his hours will be, how he’ll do the job, and what his future might be — Brett

So does everybody. The difference, among those who even take any action to do something about it, is between saying "we shouldn't put up with this! we should all do something about this so nobody has to be beholden to someone else like that!", and those who say "I'm not going to put up with this! I'm going to be the one people are beholden to, not the one beholden to people!" -

The hard problem of materialism - multiverseI wouldn't call panpsychism mainstream at all. The main ideologies seem to be "materialism" (physicalism) and Cartesian dualism mixed with neo-Platonism. The contemporary proponents of panpsychism are mostly physicalist, and prefer it over emergentism because emergentism has uncomfortable shades of dualism.

-

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageI find it unlikely that by saying something like "The Holocaust was wrong," we are literally prescribing a course of action for the dead perpetrators. Rather, I believe that we are presenting an evaluation on the moral fact of the matter. — Tarrasque

I take those, prescriptions and evaluations, to be more or less the same thing: the impression of opinions with world-to-mind direction of fit. I guess this is as good a place as any to move on to that, which was to be the next part I wanted to discuss after impression and expression, but since nobody's commented on that yet and we're already talking about this, I may as well go on about that now.

The short form of how I disagree with expressivism, to the motivations for which I am otherwise quite sympathetic, is that I hold moral utterances to not be expressing desires any more than descriptive utterances express perceptions. Rather, just as descriptive utterances impress beliefs, I would say that moral, prescriptive utterances impress intentions.

I've already elaborated on the difference between expression and impression above, but to elaborate on this difference between desires and intentions, and the analogous difference between perceptions and beliefs: In the field of moral psychology, there has been debate over the nature of "moral beliefs", which we can say are more or less the mental states communicated, in one way or another, by moral utterances. The two main sides of that debate are the Humeans and the Kantians. The Humeans hold that beliefs, properly speaking, that is to say cognitive states of mind that can possibly be true or false, are either about definitional relations of ideas to each other (as in logic and mathematics), or else about expectations of sensations or perceptions, and that everything else is mere sentiment or emotion. They agree with the argument from queerness that a "moral belief" would be a very strange thing, asking exactly what difference we would be to expect in our perception of reality if we held some "moral belief" instead of another. Finding no answer to that question apparent, they conclude that there actually are no such things as moral beliefs, only sentiments, emotions, feelings, specifically desires for things to be one way and not another. Kantians, on the other hand, bite the bullet of the argument from queerness, and affirm that there are such things as moral beliefs, that are capable of being true or false.

I find this Humeanism vs Kantianism to be a false dichotomy, and moral expressivism vs moral realism to be a false dichotomy as well. I think, like the Humean, that there are no such things as "moral beliefs" per se, and that moral utterances do not have any meaning to be found in some description of reality; but I also think, like the Kantian, that moral utterances do much more than just express desires incapable of being correct or incorrect. My position is not even that moral utterances impress desires, because I hold that desires are not the only mental state besides beliefs, and that beliefs are not the only cognitive mental states either, capable of being correct or incorrect. I use the term "opinion" to name the overarching category of mental states I am going to subdivide here, and I analyze an opinion as something I term an "attitude" toward something I term an "idea". The idea component of an opinion can be thought of as a mental picture of some possible, imaginable state of affairs, though it doesn't have to be literally visual: it is just the state of affairs that the opinion is about. But one can have different positions on different kinds of opinions about the same thing, and those different kinds of opinions about the same thing are what I mean by attitudes.

One important difference in attitude toward an idea is sometimes called "direction of fit", in reference to the terms "mind-to-world fit" and "world-to-mind fit". In a "mind-to-world fit", the mind (i.e. the idea) is meant to fit the world, in that if the two don't fit (if the idea in the mind differs from the world), then the mind is meant to be changed to fit the world better, because the idea is being employed as a representation of the world. In a "world-to-mind" fit, on the other hand, the world is meant to fit the mind (i.e. the idea), in that if the two don't fit (if the world differs from the idea in the mind), the world is meant to be changed to fit the mind better, because the idea is being employed as a guide for the world. It is the difference between a picture drawn as a representation of something that already exists, and a picture drawn as a blueprint of something that is to be brought into existence: it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match. The clearest example of this difference in attitude that I can think of is that, given the idea of a world where some people kill other people, I expect most will agree that that idea is "right" in the sense that they agree with it as a description (most people, I expect, will agree that the world really is like that, and an idea of the world that doesn't feature such a thing is descriptively wrong), but simultaneously that it is "wrong" in the sense that they will disagree with it as a prescription (most people, I expect, will agree that the world morally oughtn't be like that — whatever "morally oughtn't" means to them, which we're getting to — and that a world that features such a thing is prescriptively wrong). Same idea, two different attitudes toward it: the world is that way, yes; but no, it oughtn't be that way. Two different opinions, but about the exact same thing, different not in the idea that they are about, but in the attitude toward that idea.

I take all kind of moral language, "good", "ought", "should", etc, to be conveying this kind of world-to-mind fit.

I agree with this. Well put(assuming one of those instances of "prescribe" was meant to read "describe.") — Tarrasque

Yes, good catch, and thanks. :-)

I think there are some circumstances where a state of affairs is good, but yet, it ought not to be the case - no individual or group ought to(or, more strongly, is obligated to) act in such a way as to bring it about. — Tarrasque

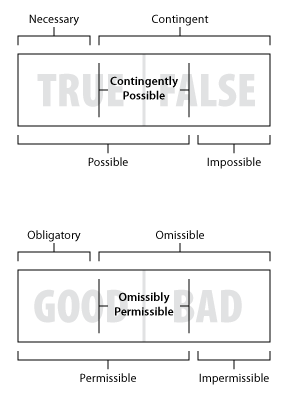

Yes I agree, when phrased in terms of obligation. Just as truth and falsehood don't capture the full range of alethic modal distinctions -- necessity, contingency, possibility, impossibility -- so too just goodness and badness don't capture the full range of deontic modal distinctions -- obligation, supererogatoriety, permissibility, and impermissibility.

Saying that someone "ought" to do something, or that something "should" be or that it would be "good", doesn't necessarily mean it is obligatory. It could very well be a supererogatory good.

I can't say I understand your opposition to non-naturalism. The argument from queerness(What would a moral fact even look like?) equally defeats all abstract facts. Yet, given your views on modal realism, logic, and mathematics, you have no issue dealing in objective facts that cannot be seen or touched. You seem not to consider them spooky. Do you consider the argument from queerness to be uniquely efficacious against moral facts for some reason? If all we can say about moral facts is that they have equally substantial grounding to other abstract facts(math, logic), that seems good enough to justify all the types of moral reasoning we like to use. — Tarrasque

I think it's important to clarify that I'm not opposed to moral semantics that are not moral naturalism, but rather to a specific stance on moral semantics called moral non-naturalism, which shares all of the same assumptions as naturalism -- cognitivism, descriptivism, robust realism -- and just disagrees on what kind of ontological things make moral claims cognitively true descriptions of reality. I object to moral naturalism for the same reasons the non-naturalist does, but I also object to most of the things they have in common, namely the presupposition that moral claims are trying to describe something about reality.

That would be the impression of an opinion with a mind-to-world direction of fit, and I think moral claims are impressing opinions with a world-to-mind direction of fit instead. This view is not robustly realist, but it's also not subjectivist, because it's not descriptivist at all. But it is still cognitivist, because I don't think that desires, non-cognitive opinions with world-to-mind fit, are the only kinds of opinions with world-to-mind fit, because there are differences in attitude besides just direction of fit, one of which, the one that makes the difference between cognitivism and non-cognitivism, I plan to discuss next, in a later post.

Correct ones of these non-descriptive but still cognitive opinions are not "facts" in the narrow sense, the sense that excludes mathematical claims. They could be called "facts" in a broader sense, but I find that that sense introduces unnecessary confusion, as "fact" seems to have inherently descriptivist connotations. The moral analogue of a "fact" is a "norm"; but NB that "norm" does not imply subjectivism, because "normal", "normative", etc, in their oldest senses, meant "correct" first and foremost, and it's only subjectivist assumptions that whatever everybody else is doing is correct that lead "normal" etc to take on the connotation of "what everyone else is doing". I don't mean it in that sense at all: a norm is just something that ought to be the case, exactly like a fact is something that is the case. -

On rejecting unanswerable questionsUnanswered vs. unanswerable is something to factor in. — Outlander

That is THE big thing to factor in, and the problem that gave rise to this whole thread. Not having an answer yet isn't the same thing as there being no answer at all.

Those two questions you gave at the end are answerable in principle. If something weird happens when you die, you'll find out when you die. If there's something inside a box, then there is some way in principle to tell what, even if in practice it's really hard.

I'm not sure if the other two questions (the heart and the ignition ones) were meant to be "unquestionable", but those are totally questionable. You don't have to take anybody's word on it. You can doubt all you want and go check for yourself. I agree that those are the correct answers, and anyone who checks them will find that they are correct, but that's different from them being unquestionable, i.e. you just have to take someone's word for them without question.

Would it clear everything up for everyone if I said instead that I am "opposed to not questioning answers and to not answering questions", rather than that I "reject unquestionable answers and unanswerable questions"? I mean the former -- don't take any answer as unquestionable, try to question them all; don't take any question as unanswerble, try to answer them all. -

The hard problem of materialism - multiverseStrong emergence/panpsychism/dualism, other non-materialistic views — Eugen

Panpsychism isn't necessarily non-materialist (assuming by "materialism" you just mean "physicalism"). One of the biggest contemporary proponents of it is Galen Strawson, who straight up titled a paper on the topic "Physicalism Entails Panpsychism". -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageWhat is your account of truth? I — Tarrasque

A pragmatist one, especially hinging on the concepts of speech-acts (different types of which I plan on discussing over the course of this thread), where what makes a statement true depends entirely on what you're trying to do by making that statement. Describing and prescribing are different kinds of speech-actions, and so each have different criteria for doing them correctly, successfully, which when fulfilled make the statements true.

I'm interested in how you suggest that mathematics has moral implications. Could you elaborate on this idea? — Tarrasque

It cannot be correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory, any more than it is correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory. ("Ought" implies "can", as you say). Mathematics is about exploring the possibilities of different abstract structures, and the limits of that possibility limit what could be moral as much as they limit what could be real.

Ought claims are made about agents, prescribing that they should take a certain action or accept a particular belief. — Tarrasque

Not necessarily. We can very well say that everybody ought to have access to adequate food and water and shelter and medicine etc, and nobody ever ought to have to die; those would be good states of affairs. Them being good states of affairs has some implications on what actions agents ought to do, but it's not directly a statement about what anyone ought to do. We can likewise make prescriptive evaluations of the past: this or that atrocity or tragedy ought not have happened, which can mean that some people in the past ought not have done certain things, but even in that case, there's nothing anybody can do about it now, so we're not telling anybody at present what to do, we're just calling something that happened in the past bad.

If someone said that you ought to be made of atoms, that would mean to me that there was something better about being made of atoms than some alternative. Even if you have no control over it, that it ought to be the case just means that it's better for it to be the case than not.

I am completely unfamiliar with modal realism, so this does not make a lot of sense to me. I think the best approach here is simply for me to try and paraphrase what you've said and wrap my head around it. I take what you're proposing to be something like this: — Tarrasque

Your take is more or less correct, but if you're more interested in the details, I just wrote a lengthy post about it in another thread, and you can also read about modal realism more generally on Wikipedia or SEP, and more about the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis specifically on Wikipedia (I'm surprised Stanford doesn't have an article on it, or even on Tegmark generally, at all). -

On the existence of God (by request)otherwise the universe is an abstraction — EnPassant

Why is that a problem?

I actually get to more or less that conclusion myself (that the universe is an abstraction), in the form of mathematicism.

In the same way that we can construct a series of sets that behave exactly like the natural numbers and so are indistinguishable and thus identical to them, so too can we construct complicated mathematical objects that behave indistinguishably from the fundamental constituents of reality and so are, for all intents and purposes, identical to them.

And it is not a special feature of contemporary physics that says reality is made of mathematical objects; rather, it is a general feature of mathematics that whatever we find things in reality to be doing, we can always invent a mathematical structure that behaves exactly, indistinguishably like that, and so say that the things in reality are identical to that mathematical structure. If we should find tomorrow that our contemporary theories of physics are wrong, it could not possibly prove that those features of reality are not identical to some mathematical structure or another; only that they are not identical to the structures we thought they were identical to, and we need to better figure out which of the infinite possible structures we could come up with it is identical to. We just need to identify the rules that reality is obeying, and then define mathematical objects by their obedience to those same rules. It may be hard to identify what those rules are but we can never conclusively say that reality simply does not obey rules, only that we have not figured out what rules it obeys, yet.

The mathematics is essentially just describing reality, and whatever reality should be like, we can always come up with some way of describing it. One may be tempted to say that that does not make the description identical to reality itself, as in the adage "the map is not the territory". In general that adage is true, and we should not arrogantly hold our current descriptions of reality to be certainly identical to reality itself. But a perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate map of any territory at 1:1 scale is just an exact replica of that territory, and so is itself a territory in its own right, indistinguishable from the original; and likewise, whatever the perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate mathematical model of reality should turn out to be, that mathematical model is a reality: the features of it that are perfectly detailed, perfectly accurate models of people like us would find themselves experiencing it as their reality exactly like we experience our reality. Mathematics "merely models" reality in that we don't know exactly what our reality is like and we're trying to make a map of it. But whatever model it is that would perfectly map reality in every detail, that would be identical to reality itself. We just don't know what model that is.

There necessarily must be some rigorous formal (i.e. mathematical) system or another that would be a perfect description of reality. The alternative to reality being describable by a formal language would be either that some phenomenon occurs, and we are somehow unable to even speak about it; or that we can speak about it, but only in vague poetic language using words and grammar that are not well-defined. I struggle to imagine any possible phenomenon that could cause either of those problems. In fact, it seems to me that such a phenomenon is, in principle, literally unimaginable: I cannot picture in my head some definite image of something happening, yet at the same time not be able to describe it, as rigorously as I should feel like, not even by inventing new terminology if I need to. At best, I can just kind of... not really definitely imagine anything in particular.

I am wholeheartedly against Platonism regarding abstract object, but I think that a kind of existence can nevertheless be applied to abstract objects after all, a kind of existence abstracted away from the more familiar notion of concrete existence.

In the most restricted sense, one could say "only what I am experiencing right here right now exists". Everything else that we talk about existing is some degree of inference and abstraction away from that. There is a position in the philosophy of time, called presentism, that holds that only the present exists, neither the past nor the future. I agree with them to the extent that in a sense only the present exists: only the present presently exists, right now. But a part of what I'm experiencing right now in the present is memory, from which I infer (automatically, intuitively, without thinking about it) the existence of other times, having an experience of moving between different times, from those remembered past times and toward projected future times, and there is a perfectly serviceable sense in which I can say that those other times "exist" in a timeless sense of the word: they don't exist now, presently, for sure, but they still exist at other times. And in that "movie", so to speak, of my past, present, and future experiences that I have now inferred, I have the experience of seeming to move around different places, so I further infer that other places exist too, besides just the here that I am experiencing now. Like with presentism, only the place I am at exists here, but those other places can still reasonably be said to exist elsewhere.

In this way, a spatiotemporal kind of existence is already abstracted away from the more primitive kind of existence relevant to my local, present experiences. But beyond that, some philosophers such as David Lewis hold, and I agree, that other possible worlds, like the kind that we use to make sense of talk of alethic modalities like necessity and possibility, really exist, and aren't just useful fictions, even though they don't actually exist, because "actual" is an indexical term like "present" or "local": it refers to things relative to the person using the word. Just as other times don't presently exist but are still real in a more abstract sense, so too, on this account, other possible words don't actually exist, because "actually" means "in the possible world I am a part of", but they are nevertheless still real in a still more abstract sense. Likewise, to finally get on to my point about the existence of mathematical objects, since we can in principle equate our concrete universe with some mathematical structure or another, and that mathematical structure definitely concretely exists (because it just is the concrete universe), we can say that other mathematical structures, i.e. abstract objects, don't concretely exist — because "concretely" is indexical, like "actually", it means "as a part of the mathematical structure that is our universe" — but they can nevertheless be reasonably called "real" in some even broader sense, the most abstract sense possible: they abstractly exist.

This completely obviates the need for any kind of explanation for why this universe instead of another, or why something rather than nothing, what's the necessity that enables all these contingencies, what's the substance that underlies all this form. Everything is just form with no mysterious substance, it's only ever features of some forms that are necessary (which is to say, their negations are impossible) so every form is merely contingent, and every form that can possibly exist does exist, while nothingness can't exist (there is no possible world at which there is no world, there is no mathematical structure that is not a mathematical structure), so since this world can exist it does, and since it features us in it, we experience it as our actual world. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageWhat differentiates the narrow sense and the broad sense as you speak of them, other than the fact that the narrow sense is physical and the broad sense is not? — Tarrasque

The broad sense is just the sense of “a statement that is correct” in any sense. The narrow sense is the sense of “a statement describing the world, that is correct”. Mathematical statements have implications about what can be real (which descriptions of the world can be correct), but they also have implications about what can be moral (which prescriptions of the world can be correct). They are more abstract than either description or prescription, and no more directly say what is real than they directly say what is moral.

If mathematical claims are not descriptive(describing a feature of reality), nor normative(counting in favor of an agent's doing or believing X), what kind of claims are they? — Tarrasque

They are statements of relations between ideas, formal logical inferences, without necessarily impressing a descriptive or prescriptive attitude toward those ideas.

A classic example of a formal logical inference is that from the propositions "all men are mortal" and "Socrates is a man" we can logically infer the proposition "Socrates is mortal". But, I hold, we could equally well infer from the propositions "all men ought to be mortal" and "Socrates ought to be a man" that "Socrates ought to be mortal". I say that it is really just the ideas of "all men being mortal" and "Socrates being a man" that entail the idea of "Socrates being mortal", and whether we hold descriptive, mind-to-fit-world attitudes about those ideas, or prescriptive, world-to-fit-mind attitudes about them, whether we're impressing or expressing those attitudes, even whether we're making statements or asking questions about them, does not affect the logical relations between the ideas at all.

Does something seem so objectionable about referring to "mathematical reality," of which our present physical reality is only one of many possible subsets? — Tarrasque

I do actually support something like this, in the form of mathematicism (or the mathematical universe hypothesis), but for me that’s really an extension of modal realism: any world that can possibly be, is, both in terms of configurations of a universe with the mathematical structure that ours has, and in terms of other mathematical structures. But claims of possibility is not made true by their accurately describing these other possible worlds, but rather by the internal consistency of the structures they posit, and the other possible worlds are limited by that same requirement of self-consistency, so they necessarily coincide.

I'll give you an additional front of queerness to grapple with. — Enrique

Not Pfhorrest, but I'll give my 2 cents. This isn't a problem unique to moral reasoning. — Tarrasque

You got it in one. Thanks. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageIf we take “fact” to mean something broader than a description of reality, then I would agree that there are non-physical facts, and moral facts are among them. I don’t consider mathematical truths to be “facts” in the same narrower sense as descriptive truths about reality are, though; and I don’t consider abstract objects to “exist” in the same sense as physical objects do either. Math is neither descriptive nor prescriptive on my account, but equally applicable to either, and its truths are not made true by the existence (in the ordination sense) of some spooky abstract objects, any more than moral truths are made true by some kind of... moral stuff. They can both still be true those, for reasons other than accurately describing reality.

-

Natural and Existential MoralityI don't think it's really relevant. The point is one can't simply compare similar methodologies and expect one to be justified because the other is. — Kenosha Kid

It’s relevant because it’s the difference between them that you cited. If you can’t describe what that difference is, then it seems like a non-difference. Imagine a world where there was an objective morality as you mean it and moral claims were predictive as you mean it. What would be different about that world compared to the way you hold this one to be? If there is no difference you can articulate, then there’s no reason to think this isn’t just such a world.

Science is justified by its predictiveness. Metaphysics are not justified by anything beyond the subjective attractiveness to the believer. — Kenosha Kid

I’m not talking about metaphysics at all, and if you think I am you’re severely misunderstanding me (as I already suspect).

All of which is subjective, not objective. — Kenosha Kid

All evidence is “subjective” in that sense. It is being shared in common between everyone that makes it converge toward the objective. Again, exact same scenario with empiricism and reality as with hedonism and morality.

I was perhaps unclear. Moral relativism is what's left when you dismiss moral objectivity as being inconsistent with or otherwise not held up by evidence. It's not a position that I feel directly needs defending; it simply emerges from what I consider a more realistic description of what morality is at root. I'm not a relativist because I find it attractive or persuasive on its own merits. — Kenosha Kid

This isn’t any different than what I was saying, it’s just put the other way around. You’ve rightly ruled out the fundamentalist-like approach to ethics, but then gone straight to relativism as the only alternative, missing the possibility of a science-like approaching to it which is neither fundamentalist nor relativist. The fundamentalist would call it relativist, just like religious fundamentalists call physical sciences relativist too. But then the postmodern social constructivist, a kind of truth relativist, claims that the physical sciences are just another totalizing dogma just like the fundamentalist’s religion is.

Both the fundamentalist and the social constructivist fail to see how the physical sciences are not just the opposite between those two, but a completely different third option. You seem to me to be in the analogous place of the social constructivist, with regards to morality: you’re rightly against the fundamentalist, but missing that my kind of position is not over there with him, but also is not over with your relativism (as the fundamentalist would claim I am), but is rather a completely different third option.

The first order is the fundamental drives and capacities that make us ultra-social animals. The conceptions we form around those -- the second-order -- are rationalisations of the first, lacking insight as to the nature of the first or the origins of the second. — Kenosha Kid

That’s not the first and second order I’m talking about. The first order I’m talking about is “what should we do?” Answers to that are certainly often informed by the drives you mention. But the second order is “how do we figure out what we should do?”

the relationship between morality and social biology would be extremely mysterious, since it would appear that humans have two very different sets of imperatives for doing the same thing: one they are born with, another they must discover for themselves. — Kenosha Kid

That’s not at all like anything I’m proposing.

Humans are also born with an innate sense of reality, grounded in empirical experience, but historically have wandered far beyond that in the search for a greater understanding of reality. The scientific method, such as it is, is an admonition not to do that, but to instead pay closer attention to and expand the range of that empirical experience we innately turn to, to find that greater understanding of reality. It’s not a choice between either just believing whatever you happen to believe or else getting lost in some dual epistemology and ontology. You can pursue a deeper understanding of reality without abandoning the innate sense of it you have, just by refining it instead.

Likewise, as you say, humans are born with an innate sense of morality. It’s grounded in a different kind of experience than our sense of reality. And we historically have wandered far beyond that in the search for a greater understanding of morality. My moral methodology is an admonition not to do that, but to instead pay closer attention to and expand the range of that experience we innately turn to, to find that greater understanding of morality. It’s not a choice between either just doing whatever you happen to feel you should or else getting lost in some dual morality. You can pursue a deeper understanding of morality without abandoning the innate sense of it you have, just by refining it instead. -

What are your positions on the arguments for God?That couldn't be further from the truth. — 3017amen

Apparently I’m not the only one who thinks otherwise:

If you have anything intelligent to say that's not a non sequitur vis-à-vis anything I've said, then now's the time to say it, 3017. Otherwise, move along; I've done you the courtesy of posting clear answers to a list of arbitrary questions, so make your tendentious point — 180 Proof

I’m not going to bother answering your long list of arbitration questions because it’s an obvious waste of time, and 180 Proof here was more charitable than you deserve in doing so himself. -

Meta-ethics and philosophy of languageI think intersection of ethics and language is a really effective way to frame the issue — Enrique

Thank you for reminding me that this thread is not supposed to be about me and Isaac yet again arguing about my entire meta-ethical system, but rather about a survey of specifically moral semantic positions and their faults and then (I hoped) a discussion of philosophy of language more generally to explore what moral semantics could be possible to avoid those faults.

The faults of the other views surveyed boil down to failing in some way or another these criteria:

-Holding moral statements to be capable of being true or false, in a way more than just someone agreeing with them, as people usually treat them

-Honoring the is-ought / fact-value divide.

-Independence of any controversial ontology (i.e. compatible with physicalism).

What you end up needing is some kind of non-descriptivist cognitivism.

I’m going to ignore Isaac’s constant harping on that first criterion above and just move on to actual philosophy of language stuff.

The first important thing I think we need to do to make sense of a non-descriptivist cognitivism is to distinguish between what I call "expression" and "impression". I think the best way to illustrate this distinction is to consider a philosophical problem called "Moore's Paradox", put forth by G.E. Moore. The paradox is that while it is clearly possible for someone to disbelieve something that is nevertheless true — all sorts of people hold incorrect beliefs all the time — there seems to be something contradictory in that person themselves stating that fact: "X is true but I don't believe X".

My resolution to this apparent paradox is to distinguish between the speech-acts of "expressing", which is a demonstration of one's own mental state, one's thoughts or feelings, and "impressing", which is attempting to affect a mental state in another person; and to highlight how, if we assume a speaker is being honest and not manipulative, we assume an impression from them upon our minds to imply also an expression of their own mind. That is to say, when they impress upon us that X is true, if we assume that they are honest, we take that to also express their own belief that X is true. If they then impress upon us that they don't believe X is true, that impression contradicts the preceding implied expression of their belief.

It is akin to shouting in a rage "I'M NOT ANGRY!". There is nothing self-contradictory in the content impressed, in either case — it's possible for someone to be non-angry, and it's possible for someone to disbelieve a truth — but just as the raged shouting expresses anger in contradiction to the impressed claim of non-anger, the utterance "X is true" implicitly expresses belief in X, and so contradicts the attendant impression of disbelief.

The more common term "assertion" can, I think, be taken to be equivalent to my term "impression" here, but I like how the linguistic symmetry of "im-" and "ex-" illustrates the distinction: to "express" is literally to "push out", and one may imagine an illustration of expression as little arrows pointing out of the speaker's mind; while to "impress" is literally to "push in", and one may imagine an illustration of impression as an arrow pointing into the listener. Though I've spoken of impressions and expressions thus far only as they apply to statements, pushing thoughts from speaker to listener, the distinction can also be applied equally to questions, where an impressed question is a direct question figuratively pulling something straight from a listener, while an expressed question is a more open-ended wondering, a demonstration of the speaker's own uncertainty and openness to input should anyone have any to offer.

Sentences of the forms "I wonder if X." and "Is it true that X?" clearly illustrate the difference. Since questions "pull" rather than "push", we might continue the clear Latinate verbal illustration by terming the "is it true" type of question an "extraction", meaning literally "pulling-out" of the listener, and the "I wonder" type of question an "intraction" — not "inter-action", but "in-traction" — meaning literally "pulling-in" to the speaker. The difference intended here is like the difference between billing someone for a service, versus putting out a hat so passers-by can donate what they like. The difference between impression and expression is likewise comparable to the difference between sending a product to someone directly, versus setting it out with a "free" or "take one" sign.

The difference between impression and expression is somewhat analogous to, but not literally the same as, the difference between the imperative and indicative linguistic moods, inasmuch as an impressive speech-act is effectively telling someone what to think (or in an impressive question, telling them to tell you something), while an expressive speech-act is effectively showing others what you think (or in an expressive question, showing your uncertainty).

However it is important to stress that I am not saying impressions are literally imperative and expressions are literally indicative, because I hold that the ordinary indicative type of statement that's generally held to be the plainest, most default kind of statement is itself a kind of impressive speech-act: saying "Bob throws the ball" impresses a belief in Bob throwing the ball, implicitly tells the listener to believe that Bob throws the ball, and so is kind of imperative-like in that way, but is still distinct from the literal imperative "Bob, throw the ball!".

Similarly, expressive speech-acts, while they are indicative-like in the manner that they communicate, can be more imperative-like in their contents, such as "I think Bob ought to throw the ball", without impressing that opinion on anyone, much less Bob himself. But, of course, we can also merely express indicative-like, descriptive opinions, ala "I think Bob throws the ball", and most importantly, I hold that we can also impress imperative-like, prescriptive opinions, ala "Bob ought to throw the ball". Expression and impression are about how an opinion is delivered; it's a separate matter as to what the contents of that opinion are.

More to come after we’ve discussed this part. -

Why aren't more philosophers interested in Entrepreneurship?The person that opened a cafe, the person that opened a factory to make shoes, the person who bought trucks to begin a transport business, the person who bought a farm and grew oranges? They aren’t employees. — Brett

They also aren't actually doing any of the work you listed, they just own the businesses that employ the people who did the work.

So the customer is an impediment. Where do you imagine the profits come from? The customer doesn’t go in the cost margin, they go in the income margin. — Brett

The production of the products or services that the customer trades money for -- the good done for the customers, by the employees -- is a cost. The money the customers trade for that is income. Income minus costs is profit -- for the owners, not the people who actually do the work.