Comments

-

On the existence of God (by request)I argue exactly that it is not mere animal faith, but a pragmatically necessary assumption. Ab initio we are forced to tacitly assume one way or the other by our actions, and to assume otherwise is simply to give up. The choice is precisely to try or else to give up.

To use your darkness metaphor, it’s all about the choice to either just sit in the dark, pretend it isn’t dark, or else TRY to find your way out of the darkness. -

On the existence of God (by request)Because any influence would give somewhere to start an explanation.

Wanting to admit an influential but unexplainable God is just wanting to declare that something is inherently a mystery just because. It’s nothing more than giving up. -

Is there a culture war in the US right now?the philosophical foundations of being ‘right’ and being ‘left.’ — Number2018

To be clear, I don't think those are the foundations of the actual left and right, just of those two stereotypes that are associated with the left and right. I think they're both a mix of left and right in actuality: their good parts are left and their bad parts are right.

am thinking may be I don't belong here at all? Which one objects to the notion that a cooperation is an individual? Which one is againt monopolies and would return things like banking and the media to several small owners? Which one understands what bureaucratic organization has to do with the shift of power from power of the people to power of the state? I am really sorry but I am very ignorant of philosophy and I don't understand what it has to do with political and economic power or lack of it. — Athena

Sorry, I'm not following how this related to the bit you're responding to. In any case, political philosophy is all about the analysis of power and authority. I'd be happy to explain more if you have some more specific questions, I just don't know where to go from here. -

On the existence of God (by request)I agree, but we need to leave a space for "unexplainable" in our deduction, even when we are trying to explain everything, therefore your 4 definitions of "god" can not cover all possibilities. — farmer

The only things that could possibly be unexplainable in principle are supernatural things that have no effects on the world, so that falls into that category of things that could count as God, but couldn't exist. -

On the existence of God (by request)unexplainable — farmer

We can never know if something is unexplainable, only that it is not explained yet.

Does it mean you put the influential [...] god in the class of "incarnate" — farmer

Yes.

I don't get the precise definition of "incarnate", but if you use "alien" as an example, seems to me it's not a good analogy for that god I describe? — farmer

That’s why I think that incarnate things are not fit to be referents of the term “god”.

You’ve got powerful aliens, the impersonal universe itself, impossible nonexistent things beyond the universe, or else some warm fuzzy feelings. None of those things except the one that can’t exist seem like they really deserve to be called “god”, so nothing that deserves to be called “god” can exist. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesMy BothAnd Blog presents many applications of the BA Principle. Yet I doubt you want to read all 107 essays. — Gnomon

Yeah I just meant a short list if examples like I gave for myself. -

Is there a culture war in the US right now?From what philosophical position can you articulate your judgement? — Number2018

The one under discussion in this thread:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/8626/the-principles-of-commensurablism

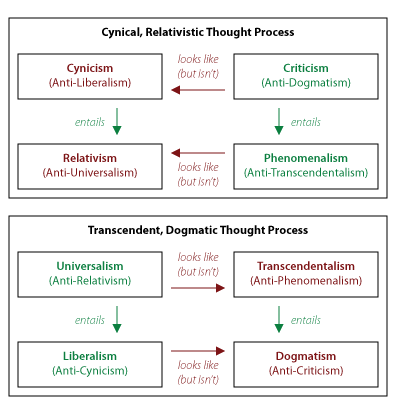

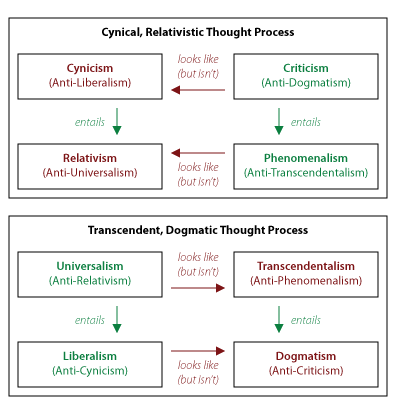

Especially as captured in this diagram:

I think the “right” “Silicon Valley Libertarian” does the top pattern with regards to norms and the bottom pattern, to a lesser extent, with an elitist lean, with regards to facts.

Meanwhile the “left” “Social Justice Warrior” does the top pattern with regards to facts and the bottom pattern, to a lesser extent, with a populist lean, with regards to norms. -

On the existence of God (by request)I agree. But when we are talking about "supernatural" god, we are not talking about a god supernaturalists refer to, we are talking about an objective supernatural god that either exists or not. So no matter how "supernaturalists" behave (as your description or not), we should not take their behavior or their definition in our account, right? And the possibility that the supernatural god is influential but unexplainable seems to me is not neglectable, which hinders your deduction on the supernatural god. — farmer

I’m not talking about what some self-identified group of supernaturalists say about themselves, rather I am saying something about belief in the supernatural myself. A god (or anything) that is influential is definitionally not supernatural on my account. -

The principles of commensurablismNone of this makes it not about psychological states. — Isaac

Only to the same degree that claims about reality could also be said to be about psychological states. There is a very plausible sense in which an ordinary claim of fact is pushing a belief or perception from the speaker to the listener, trying to induce in the listener the same psychological state as the speaker. But that is different from making a statement ABOUT the speaker’s beliefs or perceptions. The former has implications on the latter, as evidenced in Moore’s Paradox, but not vice versa. Likewise, moral claims imply things about the speaker’s psychiatry states, but they are not ABOUT them.

There's little point in continuing if you're just going to repeat stuff we've already been through. — Isaac

I agree, and I’m getting tired of repeating myself, and looking forward to this conversation ending because I really don’t foresee getting through to you.

All of the above presumes that moral statements are merely statements about what feels bad to whom. — Isaac

No, they presume that moral statements are about what IS bad (or good), and that the obvious starting point for an investigation into the truth of such statements is whether it SEEMS bad (or good) “to the senses“, the “senses” by which things seem good or bad, the appetites. Exactly as statements about what is true or false are not directly statements about who observes what, but are most obviously judged by what SEEMS true to sensorial observation. (And again, there isn’t even universal agreement that that is how to judge reality, so disagreement about how to judge morality is beside the point).

So I cannot test, in any way, the moral claim "you ought not make another person feel bad". It simply stands as an assertion, in exactly the same way as — Isaac

...”reality is whatever accords with empirical observation”.

You can’t experientially verify that experience is the way to verify things, whether we’re talking empirical or hedonic experience, verifying what is real or what is moral. That’s why discussion of these things is philosophical, not scientific. We’re discussing reasons why or why not to trust experience versus something else. You can’t turn to experience for an answer to that.

But we’ve been over this before...

there are no further tests we can carry out to check the objectivity of "god exists" — Isaac

Does God’s existence have any empirical import? That is how we check for existence after all. If so, we check if those predictions pan out. If not, then claiming that God exists is descriptively meaningless, and even if he does exist it’s the same as if he didn’t, so no matter what he’ll seem not to, and we’re to conclude he doesn’t. That’s different from the philosophical claims in the paragraph above, because neither of those is making a

claim about the existence of something. That you think my metaethical position is more like a claim about God than a claim about empiricism belies that you still don’t understand it at all. I’m beginning to suspect willfully.

To oppose that I only need point out the differences, not present arguments about the consequences of those differences. — Isaac

You really do though. If you said a white person was a better fit for a job than a black person and I asked why and all you could point to was the color of their skin, I’d be right to demand you explain why skin color matters.

1. Moral statements appear to be statements assigning properties to behaviours, they make claims that behaviour X has the property 'morally bad'. — Isaac

Already disagree on two points:

Moral judgement applies to more than just behaviors, but also to states of affairs more generally. Behaviors are just one feature of states if affairs that can be good or bad.

And “is good” does not appear to function like an ordinary descriptive property, but rather expresses a judgement in the same was “is true” or “is real” does, but a judgement with a different direction of fit than those.

2. As Moore points out, we cannot 'work these claims back' because we end up infinitely asking ourselves "but why is it bad to...?". - As in... "It is bad to punch someone in the face", "Why is that bad?", "Because it will make them feel bad and it is bad to make another person feel bad "Why is that bad?"... — Isaac

Moore meant this an an argument against ethical naturalism, and I agree with it for that purpose. He instead proposed that there must be non-natural moral facts to ground claims in, and I’m pretty sure we both disagree with that. You say you support non-cognitivism but in the end you come back to identifying moral claims as being about some descriptive, natural, psychological facts. My stance is much closer to non-cognitivism, in that I escape Moore’s non-naturalism despite accepting this argument by saying moral claims aren’t even trying to describe anything at all. But then I differentiate such non-descriptivism from non-cognitivism by saying that non-descriptive claims can still be evaluated on their own terms.

Anyway, what you’re really describing here is an infinite regress argument, and they apply equally well to claims of fact too. (This is what I mean about you “demanding” things of normative claims that you don’t demand of factual claims). Why is X true? Because Y is true. But why is Y true? Because Z is true. But why is Z true? Etc. You either pick some brute fact that you don’t question (foundationalism), some circle of reasons collectively equivalent to a brute fact (coherentism), or you accept that nothing can ever by justified... or, you stop asking for complete ground-up justification before admitting things as tentative possibilities in the first place, and instead focus on weeding out possibilities that have active problems.

Back on the topic of the OP, that last bit is precisely what my principle of “liberalism” says to do. Without differentiating between factual or normative claims, because there’s no reason to.

3. As such, the assignation of 'morally bad' to a behaviour must be either a brute fact of reality — Isaac

You still think moral claims are trying to describe reality.

4. The latter fails to explain the otherwise unlikely coincidence of assignation across cultures (there's a universal sense one must 'justify' harming another whereas one need not 'justify' going for a walk - harming another seems to be a special category of behaviour). So we accept the former, behaviours being morally bad is a brute fact. — Isaac

Or we tentatively accept the fallible appearance of certain behaviors seeming bad, and focus instead on sorting them into those that continue to seem so consistent with more such appearances, and those that don’t.

5. So the question, whence the brute fact. Either it is of the physical realm, or it is of its own realm. Inventing realms just to hold propositions when they can be easily explained within the realm we already believe in is non-parsimonious, so we reject the latter. — Isaac

If moral claims were describing reality, this would be a good point, but since they’ve not, it’s irrelevant.

I just want to be clear that I am absolutely a physicalist and do not posit any kind of moral realm or anything like that. If you think I am, you gravely misunderstand me. Normative judgements are a different kind of judgement about the same world as factual judgements, and normative claims assert those judgements the same way factual claims assert factual judgements.

Basically, propositions about physical reality have an obvious candidate for the mechanism by which they are made true. An external physical reality. — Isaac

In other words, empirical experience. Things looking true or false.

Normative propositions have no such obvious candidate for an external truth-maker. — Isaac

It’s clear to me they do: hedonic experiences. Things feeling good or bad. -

Is there a culture war in the US right now?I was hoping this thread would be more on the culture war between what I'd colloquially term the "Silicon Valley Libertarian" and the "Social Justice Warrior" stereotypes, reckoned "right" and "left" respectively, though inaccurately. (The true right is the worst of both, and the true left the best of both).

That's a much more philosophical culture war, as both sides are philosophically wrong in one way about factual matters and philosophically wrong in the opposite way about normative matters, but they've got which kind of wrong they are about which direction of fit reversed from each other. (And also a populist vs elitist leaning in one of their kinds of wrongness each, hence the left vs right gloss they get painted with).

Maybe I should start a different thread on that, if anyone's interested. -

Time and Sir. Roger PenroseThat math is a bit over my head tonight, but as I understand it time is always up in a Penrose diagram, yes, even a tiling one.

-

Panspermia - seeding the universeI don’t know that seeding life on other worlds would be an ethical thing to do. It would be a cosmic version of invasive species, and disrupt other ecosystems that have or could evolve on those other worlds, for no benefit to us or the life of our ecosystem (presuming we manage to preserve it and ourselves here).

Now sending robot probes out to observe, catalogue, and preserve other life out there, and to husband the life cycles of the stars themselves to preserve our and their lives, that is a worthwhile endeavor. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesI'm glad you chimed in here! I was hoping you would elaborate. On your system as an example here. Can you give a few examples of views on different subjects that your BothAnd principle entails, e.g. the kinds of subjects I gave examples of in the other thread (ontology, epistemology, philosophy of mind, will, ethics, politics, etc).

At that part you quoted, I am writing for an audience assumed to be mired in an object-oriented ontology, describing the differences of my view in the terms of their view.

I am curious if you read through the end of that essay, where things get much less traditional, and also through the previous essay on logic and mathematics, which dovetails into this one (as does the following essay on the mind).

The ultimate ontology I have is one of a network of interactions which are simultaneously phenomenal experiences of and also physical behaviors of objects that are also all subjects (as covered more in the essay On the Mind) that only exist as nodes in that network, defined entirely by the interactions/experiences/behaviors they take part in.

The interactions/experiences/behaviors are the most concrete things in existence, and the objects/subjects they are of are abstract constructions whose existence is like that of numbers and other abstract entities (as covered more in the essay On Logic and Mathematics).

What you describe below sounds quite a lot like that overall picture, so I'm wondering if you got the overall picture or just clicked straight to Ontology and stopped where you saw something objectionable.

Even Whitehead is part of the problem, not part of the solution — apokrisis

Can you elaborate on this? Because on my understanding of Whitehead, his view is quite similar both to mine and to what I gather is yours. -

What criteria should be considered the "best" means of defining?Wow okay, that's not even "descriptivism" as I've ever seen it, and I have no idea how you can manage to communicate on a first-order level much less communicate about communication while rejecting all of those things.

BTW, on that last note:

If two people think each other are using a word wrongly, one of them must be right and the issue must be reconciled — Adam's Off Ox

I don't think one of them must be right. It's possibly they're both wrong. But at least one of them must be wrong, if they think they're speaking the same language. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?There is a fundamental reason why the first and last of these are morally inferior positions, and it has nothing to do with any mind-independent moral objectivity and everything to do with the real biological basis of our morality: those views are fundamentally hypocritical and antisocial — Kenosha Kid

In other words, they are inconsistent and biased, not treating the same things in the same contexts the same way regardless of the individuals involved. Which is exactly the opposite of objectivity. The problem with those is precisely that they are non-objective; they only seem, subjectively, good to a few people, disregarding any concern for consistency or neutrality, i.e. objectivity.

Doing no harm is easy enough, but is it better to do good than do no harm, is it better to do good for 10 and harm 1 than do no harm, etc., etc. [...] You have existence, and you have freedom, and there is no telling what you should do with it. [...] Your morality is what you do with the choices you're given [...] And whatever you do, this is you, making you as you go along, and as long as you're not antisocial (and most people with power still are) and fall into the group above, there's no should. — Kenosha Kid

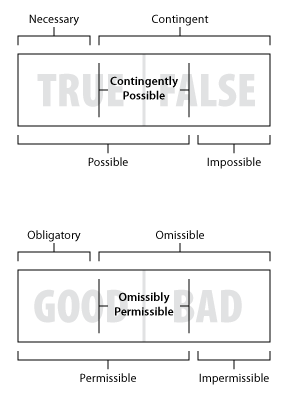

This is where modal (with a d, not an r) reasoning becomes important. On my account of morality, doing good (rather than just no harm) is only a supererogatory good: it is not obligatory. Supererogatory goods, I remind you, are the moral equivalent of contingent truths, just as obligation is the moral equivalent of necessity. Something contingent is non-necessary, it is possibly not; and something supererogatory is non-obligatory, it is permissibly not. But contingent things can still be true or false, and supererogatory things can still be good or bad.

So it sounds like we are in agreement. You are not obligated to do goods above and beyond simply not doing harm. There are many things that are permissible. Just like any truth that isn't logically necessary is merely possible: it might be true, but it might not. But we can still say, of the many possibilities, which are more likely than others; and some of them will in actuality be false, even though they were possible. And likewise, of the many permissible courses of action, we can say which are (morally) riskier than others, more probably going to end up bad; and some of them will in actuality be bad, even though they were permissible. -

The principles of commensurablismWhat a thing is or is not prima facie is not an objective fact but another statement of your psychological state. — Isaac

I quoted what you agreed was prima facie too. You said "apparently normative statements" yourself; they appear normative to you too, but you think that appearance is deceiving. And you know, we could always ask the speakers themselves what it is they're trying to do. I strongly doubt a majority of them will say they're just expressing their feelings. If so, then we wouldn't have moral arguments.

At face value people who pray very much appear to be speaking to an all powerful God. People who put ivy over the door appear on face value to be sending messages to actual evil spirits. Neither can be disproven. Are you suggesting we take no further steps to assess the likelihood of each prima facie belief but simply presume they're true? — Isaac

They appear to believe they are doing those things, in the same way that people making moral claims appear to believe that they are true. Those are examples of descriptive, (purportedly) factual beliefs though, not prescriptive, (purportedly) normative beliefs, though, so we check them in respectively different ways.

I can easily check if God or evil spirits actually seem to exist as far as my experiences go: I can try praying or hanging ivy over the door and see if anything different seems to happen. If not, then those beliefs won't seem true to me, and I'll be inclined to disagree unless they can walk me through something that does make them seem true to me. If we all check each other's claims against our experiences thoroughly like that, then we can gradually build up consensus about what seems to be true or false universally.

And I can likewise check if supposedly bad things actually seem bad as far as my experiences go: I can undergo those supposedly bad things and see if they feel bad. If they do, then yeah, I'll be inclined to agree that those are bad. If not, then I'll be inclined to disagree unless they can walk me through something that does make them feel bad to me. If we all check each other's claims against our experiences thoroughly like that, then we can gradually build up consensus about what seems to be good or bad universally.

You are denying somehow that the latter counts the same way that the former does. If I tell you that it's bad for people to get punched in the face, and you disagree, you can try getting punched in the face, and I expect you'll agree that that sure seems bad!

Maybe you can point out how the only available alternatives to getting punched in the face would seem even more bad, and that would be a sound argument for why in that context getting punched in the face could be okay -- like undergoing the pain of dentistry to avoid even greater future pain of tooth decay -- but in that case you'd at least be agreeing on the criteria by which we can assess such things.

Or you could agree on those criteria, but just disagree that anyone's experience but yours matters -- you getting punched in the face is bad, but it doesn't matter whether anybody else gets punched in the face -- but then we're back to the moral equivalent of solipsism, and you presumably reject solipsism about reality, you continue believing in things you can't currently see, so this isn't asking anything more than that.

Yes, and non-cognitivists feel they've adequately met that burden. The fact that they haven't convinced you personally doesn't damn the entire enterprise. — Isaac

You haven't put forth any of their arguments here, just said that they disagree with me and you agree with them. But I suspect the main thrust of it is that moral facts would be a really weird kind of fact, necessitating the existence some kind of bizarre non-physical stuff. And I agree, which is why I don't strictly think in terms of in "moral facts" or "moral beliefs", though I might sometimes sloppily use that common language. Morality is not about facts, or reality. Moral claims don't imply the existence of anything. It's not like I think there's some big object out in deep space, or in some other dimension, or some abstract Platonic realm, that is "the objective morals", that we can somehow find.

Prescription is a different kind of speech-act than description, and saying that prescriptive statements can be evaluated for their correctness doesn't have to have any implications on any descriptive statements at all. I am a non-descriptivist about metaethics myself, which is often lumped under non-cognitivism, but there are non-descriptivist cognitivist metaethical views, like my own. They are newer and so far rare, but they address all the complaints non-cognitivists have about moral realism without throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Again, where have I asked for proof. The fact that I don't find the position plausible is not this obstinate demand you keep trying to caricature it to be. — Isaac

I'm not saying you're actively asking me to give you proof. Just that you're rejecting the very possibility of there being any correct normative assertions, in such a way that one would first have to prove some normative assertion correct from the ground up in order to convince you of any. I know you're not asking to be convinced, but your apparent standards of evidence are unreasonable.

Yes. But I don't. Because I find the idea of an external reality more plausible than I find the idea of an objective morality. — Isaac

So your argument here is just "I disagree". That's not much of a rebuttal of anything.

I don't know how many times I have the interest to keep saying the same thing... Because facts and norms are two different things. I'm not obliged to find arguments for realism in either case equally plausible. — Isaac

Unless you can point our relevant differences between them that deserve different treatment, then on pain of hypocrisy you are.

My entire argument here is just asking what's the relevant difference that makes one deserving of different treatment than the other. Your response so far seems to be just "I feel like treating them differently, like these [non-cognitivist] guys do." The non-cognitivists at least have supposed reasons. I'm happy to shoot those down. But you're not even appealing to them. -

What criteria should be considered the "best" means of defining?I am not saying to appeal to authorities. This is the mistake that so-called "descriptivists" always make: assuming there cannot be objectivity without authority.

Words are defined by use. If there never been any agreed-upon usage, then the word is not well-defined. Whenever a linguistic community (a bunch of people who claim to all speak the same language) agree that a word means something, that creates the definition of a previously undefined word. If later on people in the same linguistic community (who claim to be speaking the same language) find themselves disagreeing about the meaning, thinking each other are using the word wrongly, then they need to look back over their history to see who broke with the agreed-upon usage, in order to tell which of them is actually using it wrongly.

Who thinks what is right or wrong (authority) or how many think what is right or wrong (popularity) both have no bearing on the question. The history of usage is independent of both of those. Self-described "descriptivists" seem so spooked by the so-called "prescriptivists" who unjustifiably invoke arbitrary authorities that they instead turn to popularity ("if enough people do it, it's not a mistake"). I'm opposed to both of those errors. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?Understood, but an extrapolation from actual mental and cultural content still isn't independent of mind and culture. It does not contain identical content, but it contains extrapolations of real mental and cultural moral trends. — Kenosha Kid

I'm not saying to extrapolate from the trends of actual models we have to project what the final correct model will end up being at the infinitely far future. If we could do that, we would just jump straight to using that model right away.

I'm saying that if you have any means of ordering models as superior or inferior, even if you don't know what lies at the unattainable extreme in the "superior" direction, that very ordering entails that some models are less wrong than others, and increasingly approximate some not-wrong-at-all (i.e. correct) one at that unattainable extreme.

With the physical sciences, we have some way to gauge which models are superior to others (concordance with empirical experience), and that very idea of some being superior to others just is our idea of objectivism about reality. Saying there is an objective reality isn't saying that any of our models are, or even in principle ever can be, perfectly in accordance with it. Just that there is some way to gauge which are closer or further from it.

All we need for objectivism about morality is a similar notion of measuring moral models against each other and gauging which is superior or inferior to the other. (This is exactly why I call my philosophy "commensurablism").

To deny that is just complete moral nihilism, saying that no notion of morality is better than any other; that Hitler didn't actually do anything wrong, because nothing at all is "actually wrong", people just have different feelings about things.

As I recall you already deny that all moral systems are equally wrong, and think that some are less wrong than others. That's all moral objectivism is.

The rest is you conflating objectivism with what I call "transcendentalism" (anti-phenomenalism), and therefore with absolutism (or fideism, anti-criticism, excessive certainty), likely all because of reducing talk of norms to talk of facts (scientism, which entails justificationism [non-critical rationalism] about norms, which makes it a kind of what I call "cynicism", which entails nihilism via infinite regress). It looks to me like you are doing precisely the top part of this diagram with regards to moral, and likely misreading me as doing the bottom part (which which I disagree just a vehemently as the top):

-

What criteria should be considered the "best" means of defining?But I will assert that a word always gets its meaning from context. — Adam's Off Ox

I didn't say anything about them being context-independent. The empirical observations that constitute synthetic a posteriori facts are context-dependent too: a red thing is only red in a given lighting, and may be a different color in different lighting. But it's the unanimous agreement that it appears a particular way under particular lighting that constitutes the objectivity of its color.

Likewise, words can vary based on context. I said in the very same post you responded to, "the same word can have multiple meanings, so long as the uses of the word in those multiple meanings do not conflict in context". But if multiple parties disagree about what a given word means in a given context, then you settle that by looking back to see who kept with the most recent linguistic community agreement on that, vs who broke with that agreement. -

The principles of commensurablismI think it is more parsimonious to consider moral statements to be no more than they evidently are until we have good reason to change that. — Isaac

Prima facie they are attempts at asserting that something actually ought to be some way or other. You yourself in this same post say:

apparently normative statements are actually just expressive — Isaac

I say to just take that appearance at face value. People are trying to say things about what ought or ought not be, not just describing themselves, and they treat other people saying different things of that sort as contradicting their claims about what is moral, not merely describing a difference between themselves as people. That indicates that they are trying to claim that things objectively ought to be one way or another, not just trying to describe how some things make them feel. Non-cognitivism claims that they aren't really doing what they superficially seem to be doing, usually because doing that thing is held to be impossible.

The burden of proof lies on the one who's saying that something is different than it seems, and that something or its negation is not possible. The starting point of any investigation is that anything and its negation is possible and so things might well be just how they seem until there's reason to think otherwise. You're saying that people making moral claims aren't really doing what they seem to be doing, and that the thing they seem to be doing isn't possible. I'm saying that there's no reason to think that, to think otherwise than that people are doing what it seems they're doing (making normative claims) and that that's a possible thing to do (some of those normative claims could be correct, and so their negations incorrect).

Since there's no evidence of an objective 'ought' it makes sense to assume there's no such thing until we have reason to believe there is. — Isaac

There cannot be evidence either for against objectivity of either reality or morality. All there can be evidence of is that we either have so far, or else have not yet, succeeded in some attempt at modelling some part of our experiences or not. In the physical sciences, we have so far had tremendous success in many ways, but not yet had success in other ways. (Which is just to say, science isn't done; there are unsolved problems, that we merely assume we can eventually solve). In ethics, we have so far had less (but non-zero) success, and the remaining challenges have just not yet been overcome.

Objectivity is an attitude to take in the approach to these topics, not something we can find "out there". We cannot escape our own limited experiences; we can only make assumptions about what is beyond them, and we cannot help but tacitly make such assumptions whenever we act. Objectivity or not is thus merely a question of how to act: try to make sense of things as an unbiased, unified whole, or else don't try.

Why do you caricature my position as 'demanding' whilst yours (which you are no less attached to, is painted as the more reasonable? — Isaac

I proceed open-mindedly on the assumption that some normative claims might be correct in what they appear to be saying, yet also critical of each of them, mindful of ways that would show it to be wrong. You instead cynically want proof from the ground up that it is even possible at all for any normative claim to be right in what they appear to be saying. That guarantees that you "have" to reject all of them, because it initiates an infinite regress: any proof of any "ought" will be another "ought" and you'll require proof of that first which will be another "ought" for which you'll require proof ad infinitum. But the same problem applies to claims of fact...

Who said I'm falling to acknowledge that factual questions are vulnerable to that line of attack. — Isaac

...because if every "is" statement required proof before it could be accepted, that proof would be another "is", which would in turn require further proof, which would be another "is", which would require further proof, ad infinitum. If you subjected factual questions to this same degree of cynicism, you would be a nihilist about reality too.

But instead, if I understand you at all, you accept that reality is at least possibly as it seems (to the senses, i.e. empirical experiences), until something else seems (empirically) to contradict that, and then you look for a new model that accords with all of that empirical experience. You don't (I think) demand that every claim of fact be proven incontrovertibly from the ground up. That would be impossible, as I think you know.

If you took that same open-minded but critical approach to morality, then you would accept that morality is at least possibly as it seems (to the appetites, i.e. hedonic experiences), until something else seems (hedonically) to contradict that, and then you'd look for a new model that accords with all of that hedonic experience. But instead, you seem to want incontrovertible proof of any normative claim at all, before you'll accept the possibility that any of them might be right. That kind of proof is as impossible for norms as it is for facts.

But that's not a problem for your approach to facts, so why is it a problem for an approach to norms? -

What criteria should be considered the "best" means of defining?When people disagree about what words rightly mean, we must have some method of deciding who is correct, if we are to salvage the possibility of any analytic knowledge at all; for if, for example, one person in a discourse insists that to be a bachelor only means to live a carefree life of alcohol, sex, and music (ala the Greek god Bacchus from whose name the term is derived), with no implications on marital status, while another person insists that to be a bachelor only means to be a human male of marriageable age who is nevertheless not married, with no implications on lifestyle besides that, then they will find no agreement on whether or not it is analytically, a priori, necessarily true that all bachelors are unmarried.

Such a conflict could be resolved in a creative and cooperative way by the use of qualifying terms to specify which sense of the word is meant: for example, the aforementioned disagreement might be resolved by the creation of the terms "lifestyle-bachelor" and "marriage-bachelor" to differentiate the two senses of the word "bachelor" in use. Or the same word can have multiple meanings, so long as the uses of the word in those multiple meanings do not conflict in context. (Initially, all words mean anything, and in doing so effectively mean nothing; it is the division of the world into those things the word means and those it doesn't that constitutes the assignment of meaning to it.)

But if no such cooperative resolution is to be found, and an answer must be found as to which party to the conflict actually has the correct definition of the word in question, I propose that that answer be found by looking back through the history of the word's usage until the most recent uncontested usage can be found: the most recent definition of the word that was accepted by the entire linguistic community. That is then to be held as the correct definition of the word, the analytic a posteriori fact of its meaning, in much the same way that observations common to the experience of all observers constitute the synthetic a posteriori facts of the concrete world. -

The principles of commensurablismNorms are not facts, yes, but that is a difference only of direction of fit (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direction_of_fit), which says nothing at all about whether one’s opinions about what is normative are any differently apt for evaluation than one’s opinions about what is factual. You are merely assuming that they are not, and on account of that refusing to address the contents of those normative opinions at all, focusing instead only on the facts about people having those opinions. You’re just declining to engage in the conversation about what is or isn’t normative, which has no bearing whatsoever on that conversation.

You’re doing essentially the same thing (but in reverse) as the social constructivist who claims that all assertions of supposed facts are in actuality just social constructs, ways of thinking about things put forth merely in an attempt to shape the behavior of other people to some end, in effect reducing all purportedly factual claims to normative ones. In claiming that all of reality is merely a social construct, such constructivism reframes every apparent attempt to describe reality as actually an attempt to change how people behave, which is the function of normative claims. On such a view, no apparent assertion of fact is value-neutral: in asserting that something or another is real or factual, you are always advancing some agenda or another, and the morality of one agenda or another can thus serve as reason to accept or reject the reality of claims that would further or hinder them.

I imagine you disagree with that kind of view vehemently (as do I), but it is simply the flip side of the same conflation of "is" and "ought" committed by scientism like yours: where scientism pretends that a superficially prescriptive claim can only be evaluated in terms of descriptive claims, constructivism pretends that all descriptive claims have prescriptive implications.

Constructivism responds to attempts to treat factual questions as completely separate from normative questions (as they are) by demanding absolute proof from the ground up that anything at all is objectively factual, or real, and not just a normative claim in disguise or else baseless mere opinion. So it ends up falling to justificationism about factual questions, while failing to acknowledge that normative questions are equally vulnerable to that line of attack.

Conversely, scientism like yours responds to attempts to treat normative questions as completely separate from factual questions (as they are) by demanding absolute proof from the ground up that anything at all is objectively normative, or moral, and not just a factual claim in disguise or else baseless mere opinion. So it ends up falling to justificationism about normative questions, while failing to acknowledge that factual questions are equally vulnerable to that line of attack.

Either error results in simply refusing to consider one kind of question, which is why both run counter to my principle of cynicism, because they inevitably lead to nihilism of one sort or another. -

On the existence of God (by request)Yes, and I do equally advocate keeping in mind the possibility of losing. But that just means not being arrogant about your current play: it’s always the case that THIS might not be THE winning play, even though we must always act as though there is A winning play. I call those principles “criticism” and “objectivism” respectively.

And my critique of supernaturalism is grounded in criticism more than objectivism. The supernaturalist posits that there is something out there that is objectively real (so far so good), but beyond our ability to investigate. So any opinion we hold on it must just be taken at someone’s word — maybe just our own — without question, which is exactly that kind of arrogance that “THIS is the winning play” that my principle of criticism is against.

We must always proceed on the assumption that there is some answer or another out there, but that any particular proposal might not turn out to be it, if we want to have any hope of narrowing in on whatever the right answer is, if that should turn out to be possible. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?By lieu of it being an extrapolation of subjective opinions, it is not mind-independent, for instance. — Kenosha Kid

Being at the unattainable limit of that series, it is independent of anybody’s particular mind. It is composed entirely of mind-accessible stuff, but people thinking that it is this or that way isn’t what makes it what it is. People just have limited access to it in practice, though all of it is accessible in principle, so they can at best access and incomplete approximation of it. But the series of increasingly more complete approximations points us at whatever lies at the end of that limit.

When I've been saying 'objective reality', I've tried to distinguish between the putative reality supposed by scientists, i.e. that which models tend toward, and an empiricism-independent objective reality that is the simplest and best explanation for the former. — Kenosha Kid

Nothing needs to be empiricism-independent to be objective. You are conflating objectivism with what I call “transcendentalism”, that being anti-phenomenalism, empiricism being the description half of phenomenalism.

It’s the difference between being mind-independent and mind-inaccessible. We can never know anything about any reality that’s non-empirical; we’d just have to take someone’s word on it. The only reality that we can know and interrogate and try to come to grips with is the empirical one that we have direct but incomplete access to.

s/reality/morality and s/empirical/hedonic -

The destiny behind free will: boom this is deep stuff!any good parent — tim wood

This reminds me of a way I’ve sometimes got phrased my compatibilist position: free will is like self-parenting. Your parents can influence the choices you will make. You can influence the choices your children will make. Free will is just bending that in a loop: influencing the choices you yourself will make in the same way your parents influence you and you influence your children. The stronger an influence you have over yourself like that, to the exclusion of other influences, the freer your will. -

On the existence of God (by request)I mean that considering the explainability of every particular thing to be unsettled (each thing might be explainable or it might not) is the least assumption. It’s the shrug emoji of answers.

(But as soon as we act, we tacitly assume more than that, in one direction or the other). -

On the existence of God (by request)I think the opposite is what you called "non-cognitivist — farmer

No, non-cognitivism is using words in a way where truth isn’t even something that applies to them, because they’re not trying to convey literal truths at all, but rather e.g. to evoke emotions.

I think "there might be something that is unexplainable" is a more gentle presumption than "anything is explainable". Because the fact that the world is explainable itself is not explainable ( or at least not explained), as Einstein said similarly. I suppose the burden of proof is on the "anything is explainable" side. — farmer

“Anything might or might not be explainable” is the least assumptive position. Burden of proof is on anyone who would vary from that either direction. But in our actions we cannot help but belie a tacit assumption one way or another: that explanation is in principles possible (belied by trying to find it), or that it’s not (belied by not trying). Assuming it’s not, by not trying, guarantees that you won’t. Assuming it is, by trying, doesn’t guarantee anything, but it leaves open the possibility that you might. That is a pragmatic reason to act always on the assumption that explanation is possible, by trying, and never on the assumption that it is not, and so giving up. -

On the existence of God (by request)how do you consider a case that the consequence of god's activity can be observed but it does not appear in regular as a natural phenomenon like wind, therefore some people do observe the evidence of god, but can not record it so mankind can not have an agreement on god's existence. — farmer

If it does not at first appear regular, even just to one individual, or does not appear accessible to all individuals equally, then we need to figure out what the differences are between the circumstances when it does appear and when it doesn’t, and between the people to whom it appears and the people to whom it doesn’t. We must proceed on the assumption that there are some such differences that account for the apparent irregularities, because to do otherwise is simply to assume that the phenomenon is inexplicable, rather than that we simply haven’t explicitly it yet. More on that below.

I think there is a presumption of your classification of god: that you know the definition of "nature". However the human definition of "nation" is evolving, thousands of years ago, humankind considered lots of things as mysteries, "supernatural", "nature" is underestimated by them, and now you believe everything you experience is natural, in the faith that science will eventually explain everything. Is this belief well-founded? — farmer

There is a difference between something being unexplained and something being unexplainable. There can be all kinds of unexplained phenomena, even ones people would want to call “paranormal”, without any if them being unexplainable in principle. And if we would like to explain things where possible, we must try to do so. But if we assume it is not possible then there is no point in trying, in which case if that assumption is wrong and it is possible, we will never find out. So we must proceed always on at least a tacit assumption that such explanation is possible, and that things we haven’t explained yet just haven’t been explained YET, not that they can never be explained. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?It is interesting you bring up the idea of limit. I'm not sure if you mean this as a metaphor, or as a literal model of what you are trying to convey. — Adam's Off Ox

I do mean it in the same sense it is used in calculus, something that a series asymptotically approaches, but I don’t mean it to be the exact sense of the limit of a numerical series. I guess you could call it a qualitative rather than necessarily quantitative version of a limit. Though in cases where it is possible to quantify the thing in question, I guess such a qualitative limit becomes the same thing as the ordinary quantitative limit, making the former concept perhaps a conservative extension of the latter.

From what you say, I gather that objectivity is binary. I also gather that an objective claim can either be correct or incorrect. While no idea can be more correct than correct, I gather you are saying some ideas can be more incorrect than others. — Adam's Off Ox

Yes. It is the old idea of being less wrong, as in

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Relativity_of_Wrong

This is an interesting description of what we do with science. I would have described the method differently. Could I ask you, do you have hands on experience with science? Have you done lab work in a university setting or been paid for scientific research? I ask because my experience has been different. — Adam's Off Ox

I have not, but I think I know where you are going with this, because the accounts I hear from people who have don’t generally involve thinking of things in terms like that, and that’s neither surprising nor a problem to me.

My description is a very high-level account of things so abstract they just form a background part of the norms of science that don’t usually need to be spoken about. The only time a working scientist would need to account for science in such a way is when justifying it against something radically different, like fundamentalist religion, or (back on topic) truth-relativist postmodernism.

Which would then be doing philosophy of science, or epistemology more generally, which is why such things are discussed more in those fields, and not among working scientists. -

Architectonics: systemic philosophical principlesMy approach to dichotomies treats them as the mutual limits on possibility so you are always talking about relative states of affairs. So "world" and "mind" are just complementary bounds on being. As humans, we have to develop a habit of reality modelling where our consciousness feels sharply divided into "a world" that then has an "us" in it - the "experiencing ego".

So the world becomes defined as that part of being which has the least of that us-ness. And the us is the part which has the least degree of the world. The fact of that construction is shown by something as simple as finding your arm is dead after you slept on it.

My reading of your diagram followed this pragmatic logic. We have to construct "the world" to construct our "selves". And vice versa. It is a two way psychic street. This contrast with Cartesian dualism where both world and mind are granted substantive reality. It is instead the basis of what Peirce called his objective idealism. Or Kant, his transcendentalism. (If you ignore the lingering religious leanings of both of those two.)

So I see your whole map as a map of the pragmatic effort to construct the reality of being. It is not about the Cartesian project of a mind-soul that knows the world in a passive but directly perceiving way. It is a pragmatic Peircean consciousness where we are refining the intellectual tools to work on both sides of this act of co-construction. One side of the knowledge map is focused on technical control over the appearance of the world. The other is focused on the technology for the making of a complex modern selfhood.

It may or may not be what you had in mind explicitly. But it is what jumps out for me. — apokrisis

Yeah, I figured that was what you meant, and that is the kind of “blended” objectivity-subjectivity that I see incorporated on both sides, neither emphasizing one more than the other. Rather, they differ in something called “direction of fit”:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direction_of_fit

And I've rarely seen something that makes as much sense. Is this diagram something you have published or planned to? — apokrisis

Thanks so much! This diagram is a central part of a book / series of essays I recently finished. It’s currently only self-published on my website (link in user profile), and I don’t have any plans for professional publication, mostly because I lack confidence that it’s good enough for that.

So maybe those two segments should be same sized - mirror images.

And maybe you are saying that dynamics/calculus are geometry plus time, while harmonics/trigonometry are algebra plus space? So rather than four quadrants, you have two halves with their subset extensions.

And does arts chop up the same way? — apokrisis

The sizes in those two hexagons aren’t meant to be indicative of anything, it’s just hard to divide up a hexagon into four nicely.

The four parts of mathematics are meant to be more or less the quadrivium of classical education:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadrivium

which are sometimes rendered as “number in itself” (“arithmetic”), “number in space” (“geometry”), “number in time” (“music”), and “number in space and time” (“astronomy”).

The arts divisions are meant to be a mirror of that as well, yes.

On logic vs rhetoric, what I think the diagram gets right is that language is conventionally divided up into the three things of syntax, semantics and pragmatics. So it is neat that logic is syntax/semantics - the technology of argumentation with the least possible constraint in terms of pragmatic embeddedness, while rhetoric can be defined in contrary fashion as the technology of argumentation with the least possible constraint in terms of syntactical correctness.

Was that a lucky accident or your conscious intention there? — apokrisis

That was on purpose yes, glad you caught that. :)

I would really love to hear you take on my whole book that this chart / the principles of the thread this thread forked off of are from. You have a great eye for little structural details like this that nobody else seems to notice or care about, and those are to me the most novel and important parts.

Another random point is that Maslow's psychological hierarchy of needs could be a useful way to structure the human side of the equation - the hierarchy that goes from basic survival needs to self-actualisation. Securing the physics of life - energy and integrity - and then continuing towards the sociology of free individual action.

That might reorder the trades hexagon, for example. Or the ethical sciences. It seems to match the sciences hierarchy already. — apokrisis

That is an interesting idea that I’ll mull over a bit. Thanks again! -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?So do you take objectivity to be a scale as opposed to binary — in that a claim can be more or less objective than another claim? — Adam's Off Ox

Not quite. Objectivity, as in making an objective claim, a claim that something is objectively correct, is binary. Either you are saying that this opinion is the right one, for everyone, or else you're just saying that it's the one you happen to have. (I call this distinction between these different kinds of speech-acts "impression" vs "expression", and while I do think that impressions are kind of imperative-like in that they are trying to get others to think some way, and expressions are kind of indicative-like in that they are just showing what you think, both impressions and expressions can have descriptive content or prescriptive content, which are respectively also indicative-like and imperative-like in different ways).

Objective reality/morality is the limit of a series of increasingly improved subjective opinions on what is real/moral. There being such a thing as "improvement" in subjective opinion is the only practical consequence of there being such a thing as objectively correct, since as it is a limit it can never actually be reached. There being something objective in principle just means that differing subjective opinions are commensurable: one can be less wrong than another, rather than all being equally (or at least incomparably) wrong.

Does it become more objective when more people share the experience? Are moral claims more-objective democratically? Then does that same democratic approach have any relationship to the true-ness of an objective moral claim? — Adam's Off Ox

If by democratic you mean majoritarian, then I don't think there's anything democratic about it.

When we do physical sciences, we don't take a poll on what people believe, or even what they perceive, and then say that whatever wins that poll is the thing that's objectively real, or that things with higher poll numbers are "more objective". But we do take into account everything that is observable by everybody in every context, repeating other people's observations by standing in the same context as them, and as necessary accounting for any differences between us until we can confirm. Then we come up with whatever model we have to come up with that accounts for all of those observations, even if that model isn't what anyone perceived or believed to begin with.

I say to approach ethics in exactly that same manner. It doesn't matter what anyone intends or desires, but it matters what everyone feels in a more raw way -- their experiences of pain, hunger, etc, before they're interpreted those into particular desires or intentions. We need to take account of all such experiences (which I term "appetites") had by everybody in every context, standing in the same context as them to confirm that that is actually what someone experiences in such a context, as necessary accounting for any differences between us until we can confirm. Then we come up with whatever model we have to come up with (a model of how the world should be, rather than how it is: a blueprint, not a still life) that accounts for all of those experiences, even if that model isn't what anybody desired or intended.

The limit of the series of models come up with by the physical sciences done in such a way, as we take into account more and more empirical experiences (observations) by more different kinds of observers in more different contexts, just is what objective reality is. Likewise, the limit of the series of models come up with by comparable "ethical sciences" done in that analogous way, as we take into account more and more hedonic experiences by more different kinds of people in more different contexts, just is what objective morality is.

I apologize if it seems like I am grilling you. I really do have an interest in establishing what would make an objective moral claim, or what would make a moral claim true. It's just that as I ran up against these same questions for myself, I did not arrive at a satisfying answer.

The reason I appeal to non-objective senses for sentences has come from hard lost battles with skepticism. Over time I have come to relate to a kind of skepticism which leans toward moral nihilism, not out of desire, but rather lack of certainty. — Adam's Off Ox

I didn't feel like you were grilling me, but I do appreciate you saying this anyway. It makes me feel more like I'm helping someone figure out something they've tried and failed to figure out, and less like I'm arguing with someone trying to convince them of something they don't want to believe.

You may be interested in another thread where we're mostly discussing the same topic, and more generally the principles that underlie my view on that topic and all others:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/8626/the-principles-of-commensurablism -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?So is the claim, "Everyone ought to agree that there is a lake there," also an objective moral claim, since it includes an ought (and you have already established you believe it is an objective claim). — Adam's Off Ox

No, that’s just me being fast and loose with trying to translate an ordinary “there is a lake there” sentence into the weird way you phrased the analogous moral claim.

I'm wondering how you propose we verify the correctness of an objective moral claim. — Adam's Off Ox

By appeal to experiences with imperative import, i.e. hedonic experiences, things that feel bad or feel good. Just like we appeal to empirical experiences to verify descriptive claims. But not just our own experiences at the present moment; that wouldn’t be objective. Objectivity is absence of bias, so it must be based on all experiences of everyone everywhere any time. We can never fully account for all of that, in either descriptive or prescriptive matters, but that gives us the direction to move toward more objectivity. -

What Would the Framework of a Materialistic Explanation of Consciousness Even Look Like?There are over 11 forms of pan-psychism. — tilda-psychist

@Baden I’m pretty sure tilda here is christian2017 evading his ban, as this “11 forms” thing is a stock phrase he used to repeat over and over. -

The principles of commensurablismBasically, you're making the assumption that moral statements are normative, I don't agree. I think moral statements are expressive. — Isaac

It sounds then like you are using the same words to refer to something different than I am. Rather than arguing about whose use of the word “moral” is right, I ask that you just substitute every instance of “moral” with whatever you would label something that is actually normative, because normativity is entirely what I’m talking about.

This is exactly the same is-ought problem I was just explaining to @Kenosha Kid in the postmodernism thread. If you want to reduce all attempts at prescriptive discussion to descriptive discussion, what you end up doing is just ignoring the prescriptive discussion entirely. Refusing to attempt to answer a question doesn’t somehow show that it is unanswerable. -

Postmodern Philosophy : what is it good for?Irrespective of what it's for, if it adds no understanding to moral behaviour, i.e. if morality is equally explicable without it, objective morality is at best redundant. — Kenosha Kid

It’s redundant to a descriptive explanation, sure. The point is there are things to do other than describe. To insist only on describing is just to ignore other kinds of questions entirely; case in point, prescriptive ones.

You seem to be talking entirely about why people do what they do and judge how they judge what each other do. I’m taking about why people should do this or that, and equivalently how we should judge what they do. Different questions entirely, and answering only the first sheds no light at all on the second.

What makes statement 2 objective, in that it states anything other than the personally held value of the speaker? Does statement 2 become objective because it has the word 'all' in it, or is there something else going on here? — Adam's Off Ox

It it a claim of objectivity because it says that a certain judgement is the correct one, one that should be held by everyone. It may or may not be a correct claim.

It’s perfectly analogous to the difference between “I see a lake” and “everyone ought to agree that there is a lake there” (which is a weird way of saying “there is really a lake there”). The latter is a claim of objectivity just because it’s not couched in any particular perspective. It may or may not be correct, depending on whether it really does pan out in every perspective or not.

For example, are both statements, "Killing humans is always wrong," and, "Killing is permissible by some class of humans," morally objective but incompatible? — Adam's Off Ox

They are both claims of objectivity, because they are not couched in any particular perspective, but because they are incompatible at least one of them has to be an incorrect claim. -

The principles of commensurablismMy feelings

Those are your experiences.

my neurological wiring

That’s a cause, not a reason.

unconscious following of social norms

That’s “because someone said so”.

predictions of positive outcomes for me

Gauged by your expected experiences?

God

“Because someone said so”.

the effects of the moral ether, aliens controlling me because we're living in a simulation...

Causes, not reasons. -

The principles of commensurablismIt's my behaviour to to others that seems morally good/bad to me, not my experiences. — Isaac

But on what grounds does your behavior toward them seem good or bad, if not either their experiences, or because someone else just said so? -

Dark Matter possibly preceded the Big Bang by ~3 billion years.And to add to what Enai said, in any case there is no center.

-

The principles of commensurablismYou're saying "let's assume moral goodness is equivalent in some way to hedonic pleasure" and just ignoring that fact that millions of people feel differently. — Isaac

You keep making some kind of category error in talking like these things can come apart, like the "good" and "bad" in "feels good or bad" is a different sense than in "morally good or bad". Hedonic experiences analytically just are things that feel good or bad, in the same way that empirical experiences analytically just are things that look true or false. You can doubt either one, but then you're either doubting whether these experiences you're considering are enough, or else whether any experiences matter at all.

If no experiences matter at all, then you're left either holding no opinion whatsoever on the matter, or taking someone's word for it (maybe just your own). In either of those cases, you have at best a random guess's chance (whoever's word you might choose to take) at arriving at the correct opinion, if such a thing is possible, which at this point in the inquiry we're not sure of yet. So if you want to arrive at the correct opinion, if that should turn out to be possible, and have more than that tiny chance of guessing right the first time, then you've got to proceed as though there is one, but that you can't take anyone's word for what it is -- those are my principles of "objectivism" and "criticism" -- and then try to narrow in on what it might be. And if you're doing that, the only thing you have left to turn to is the experiences of things seeming correct, of things looking true or false, and feeling good or bad.

Now that we've ruled out doubting whether any experiences matter at all, we're left with doubting whether these particular experiences are enough or not. If not, that means what you need to do is account for more experiences. In the case of moral questions, that's more experiences of things feeling good or bad -- since that's the only kind of good or bad we have left to turn to, having ruled out just taking someone's word for it. It's entirely likely that the experiences you alone are having right now aren't enough to go on. That just means that you also need to account for experiences other people are having, and experiences you and they might have later. The only direction left to turn besides that is to just give up, in one of the ways described in the paragraph above.

In what way does your approach try to "figure out what is different about ourselves and the circumstances we’re in that accounts for the differences in our experiences"? — Isaac

Bob has never had a certain unpleasant experience that Alice has had, because Bob has never been in the circumstances that Alice has been in to experience it. Bob may therefore be callous toward Alice's plight. My approach says Bob should consider the different circumstances Alice has been in, and why those would lead to different experiences that Bob hasn't had. If Bob doesn't believe Alice that those experiences in those circumstances are unpleasant, my approach says he should go stand in those circumstances himself and undergo the experience himself, to confirm that it is actually unpleasant. If still Bob doesn't find it unpleasant even though Alice reports that she does, my approach says they should look into what is different about themselves that gives rise to Alice experiencing such displeasure in those circumstances while Bob does not. The moral conclusion they should derive is that it is bad to subject people who are like Alice in the relevant way to such circumstances, because it causes displeasure in them, but it's okay to subject people like Bob to it, since those people don't experience displeasure in those circumstances.

What Alice or Bob say they believe "is morally right" isn't relevant, any more than the beliefs of scientists conducting experiments is relevant to the science. It's just the experiential data that matters. We don't ask them their opinions on hedonism, just whether things feel good or bad to them. This is why it's a category error for you to ask for this procedure to prove hedonism itself. You can't ask scientists to do an empirical experiment that proves empiricism is true without begging the question, either.

You keep repeating what you claim to be possible, and I understand that, what I'm asking is why. If I were to say "you know how when you push a ball it rolls down hill? Well so it's the same with helium balloons", you'd tell me that despite me saying they fall into the same category, they don't. It's like that with your descriptive and normative categories. All you're doing is saying that however we treat descriptive theories, we can do the same with normative theories, but you're not presenting any arguments to make your case, simply declaring that it can be done. — Isaac

I'm not just saying "it's possible, take my word for it", I'm saying nobody has given a good reason why it's not possible.

The default state of any inquiry has to be one where all the options and their negations are merely contingently possible, neither impossible nor necessarily true. This is part of not taking anybody's word on anything, leaving everything open to question, plus the necessity of giving everything the benefit of the doubt because otherwise you fall down an infinite regress and can never get any justification off the ground, leaving you stuck holding no opinions on anything again, which again is just giving up on trying. (This last bit is my principle of "liberalism").

Out of that initial state of inquiry, the burden of proof is on whoever wants to say that something is either impossible or necessary to show that the relevant alternatives can somehow be ruled out, leaving only that option for necessary truths, or anything besides that option for impossibilities.

Starting in that initial state of inquiry, I've given arguments why rejecting either of my principles of objectivism or criticism leaves you no hope of figuring out what the correct answers are, even if there are any that can be figured out, and why assuming those principles is therefore necessary. Those principles in turn entail liberalism and phenomenalism, the normative half of the latter being hedonism.

But your concern doesn't seem to be so much with hedonism vs its alternative (just taking someone's word for what's good or bad), but rather with moral objectivism. So that's a much more straightforward problem: you either assume moral objectivism, or you give up all hope of figuring out what's good and bad by simply assuming (on no grounds) that nothing could possibly be actually good or bad.

Once you're assuming moral objectivism, you can either take someone's word for what objective morality is, which is just another form of giving up on trying to be correct, or else you can question everything and try to narrow in on what might be right.

If you're going to question everything, you've got to give every possibility the benefit of the doubt, or else infinite regress quickly takes you back to assuming nothing is possible.

And if you're going to whittle away at those options you're giving the benefit of the doubt, without taking anybody's word on it, all you've left to go on is experiences of things seeming good or bad, as many such experiences as you can account for.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum