Comments

-

Heraclitus' Fire as the archeAnaximander had it right in two. The fundamental stuff of reality is boundless, formless, until it is bound and formed into particular things. Today we recognize that that “stuff” is just the potential for action: energy. Being is doing.

-

What is the difference between "doing" and "being"?To be is to do. An object is just a bundle of attributes and each attribute is just a propensity to do something in some circumstances. Nothing can exist and do literally nothing, and the whole of anything’s being is what it does.

-

How to live with hard determinismNo, I’m not saying anything about things with no causal power.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?The main interesting point of Whitehead was the idea of "corpuscular societies" vs. "compound individuals. — schopenhauer1

I’m a big Whitehead fan, and I like to take this individual-society metaphor in the other direction too. I analogize a society’s educational and governmental institutions to the mind and the will, a kind of societal self-awareness and self-control. And likewise I say that both epistemic and deontic authority are spread diffusely through society in a way that is negligible at the individual level, much like mind and will are diffused throughout the universe in a way that is negligible at the atomic scale. But in both cases, the right kind of functional structures built up out of those constituents can integrate that negligibly diffuse stuff together into something significant: consciousness and free will as we ordinary think of them in humans on the individual scale, and some semblance of academic and political authorities on the societal scale. At both scales, the important feature of this kind of view is that the “novel” thing that’s built up by the end is just a refined form of something normal that’s everywhere, and isn’t actually something wholly new that at some point suddenly starts happening in a way discontinuous with that what was already going on before.

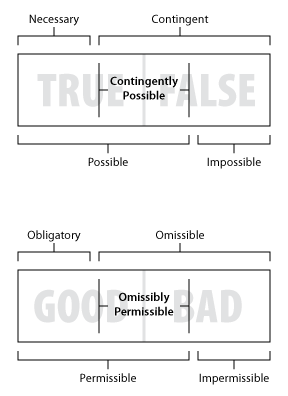

This is one of the kinds of things that I think my Structure of Philosophy helps highlight or draw attention too:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/8303/the-structure-of-philosophy -

How to live with hard determinismI’m not sure how to say more clearly than I already have. The process in question is the one whereby your practical or moral reasoning directs your behavior: where thinking that you should do something causes you to do it. The specifics of that process aren’t important right now, if that’s what you’re asking about. Just that free will as I take it consists of that process going uninterrupted by anything else, in contrast to circumstances where for one reason or another you ended up doing something you didn’t think was the best course of action.

-

God given rights. Do you really have any?It just becomes meaningless. — Gnostic Christian Bishop

Only as meaningless as any other moral claim. If someone grievously harms someone else and nobody stops it, does it become meaningless to say it was wrong? Saying the victim had a right not to be harmed is just saying it was wrong to harm her, so is only meaningless if that is meaningless too. -

Let’s chat about the atheist religion.I think you missed the point. You said all religions follow an ideology, and concluded that any ideology is a religion. The first says that ideology is necessary for religion. The second says it is sufficient. But necessity is not sufficiency.

You can have an ideology without being religious, even though you can’t be religious without an ideology. -

How to live with hard determinismJust existing somewhere has some effect on everything around you, so you’re always “doing something” in a super strict pedantic sense. But someone standing quietly out of the way just watching events usually has such little influence that nobody would notice a difference between them being there or not unless perhaps they were looking very carefully for evidence that they were there. That’s a negligible influence. That’s “doing nothing”: as far as anyone can tell, on an ordinary macroscopic scale, the exact same things happened as would have happened if you hadn’t been there at all.

What process? — I like sushi

The process ofone’s behavior being determined by one’s practical or moral reasoning — Pfhorrest -

How to live with hard determinismone’s behavior being determined by one’s practical or moral reasoning (what you think you should do), and other influences having negligible interference in that process. — Pfhorrest

-

Is inaction morally wrong?Both of those are just the simple negation of doing something.

Of course, to be is to do, so everyone is always doing something to some degree just by existing, but there is a continuum of different degrees of doing something in different contexts, and "doing nothing" / "not doing anything" in a given context is just doing negligibly much, such that the things that happen in that context are not noticeably different to what would have happened if you hadn't existed there at all.

Ok, but what Im asking is how you decided the prevention of greater loss of life in the trolley problem isnt obligatory. Walk me through your reasons for excluding it from obligatory in your diagram, I dont understand. — DingoJones

Preventing any loss of life is good, but only a supererogatory good; nobody can be obliged to prevent everything bad that happens, or even everything bad that they could possible prevent, or else you'd run into classic utilitarian problems like everybody who doesn't give everything they have and spent the entirety of their lives working exclusively for the benefit of those less fortunate than them are doing something wrong, that any concern for oneself at all is morally wrong. Sacrifice for others is good, but taking care of yourself is not wrong, impermissible; it is permissible to let bad things go unfixed (even though it's supererogatorily good to fix them), it's only impermissible to cause new bad things yourself.

In the trolley problem, the choices presented are either do an impermissibly bad thing (kill someone) to achieve a supererogatory good (save some people), or else do nothing, in which case you fail to do the supererogatory good, but you also do not do something impermissibly bad. As permission and obligation are DeMorgan duals, you are obliged not to kill anyone, and conversely permitted to not save people, so if you would have to kill someone to save people, then it becomes impermissible to save them, at least that way.

Otherwise, it would be obligatory (or at least permissible) to kill one healthy patient and harvest their organs to save five dying people. I think that counter-example pretty clearly illustrates the problems with people's usual intuitions about the trolley problem. It's not okay to murder innocents to save more innocents, even though it's still good to save those more innocents -- but only if you can do it without murdering others. -

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?Reflexive means self-referential. Reflexivity is what access consciousness is all about: having access to information about your own mental states, self-awareness in a functional, behavioral way. “What it’s like” is what phenomenal consciousness is about: what the subject first-person experience of being a certain kind of thing is. I’m saying consciousness as we ordinarily think of it is just what it’s like to be self-aware. The “what it’s like” part isn’t special to humans though; only the self-aware part is.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?As I see it, consciousness as we experience is what it’s like (phenomenal consciousness) to be a reflexively aware (access conscious) thing of the type that we are. Since everything has some what-it’s-like on my account, it’s the being-a-reflexive-thing part that matters.

-

Is inaction morally wrong?“Not doing anything” and “doing nothing” are the same thing. I rephrased specifically to avoid this confusion.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?There’s all kinds of stuff on the borders of physics and philosophy that makes all sorts of things out of QM’s observer-dependence. A lot of it is pure woo, that goes on so say everything is conscious in the ordinary way we normally mean because of it. I do identify the kind of “mind” or “consciousness” that my panpsychism is about with quantum observation, but the other way around: quantum observation is no big deal, as most contemporaries physicists will tell you, and I take “phenomenal consciousness” to be nothing more than that, and so likewise not a big deal. All of the interesting stuff that “consciousness” in its usual sense means is handled under the easy problem, as access consciousness.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?The closest we can get is maybe ideas of observer-based worlds which posits an observer in the equation as a must? — schopenhauer1

Quantum mechanics is already like that.

The catch is, anything counts as an “observer”.

In other words, something like panpsychism. -

Is inaction morally wrong?No, there are lots of supererogatory goods that someone can do to be better than morally neutral, they just aren’t obligatory. Like how saying contingently true things makes your speech more correct than merely refraining from impossible self-contradictions, where such consistency is all that’s a strictly necessary truth.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?In the form of panpsychism I defend the fundamental units of nature are “quantum events occurring in space-time”. In Whitehead’s form of process philosophy “Process and Reality” the most fundamental units are “actual occasions” which invariably have both a mental aspect and physical aspect or pole. The mental or experiential pole has to do with incorporation of elements of the past and possibilities of the future as well as relations to other events (what Whitehead calls prehension). I have a read a lot of presentations of panpsychism and this is the form which I defend. — prothero

:up: :100: -

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?No, you admitted that an eliminativist (usually a physicalist) would rule it out. — bongo fury

Yes, but in ruling it out, they’re not proposing that the weird thing happens. (But they’re also denying the most ordinary familiar thing, by conflating it with something metaphysicall weird).

Panpsychists say something happens (that familiar having of first-person experience), but that it’s perfectly ordinary and nothing weird.

Only emergentists (about phenomenal consciousness, because that’s the context here) say that a weird thing that calls for philosophical some explanation happens.

Yes, an extra, 'meta' perspective. — bongo fury

There’s nothing meta about it. Reflexive SELF-awareness, which is what I think ordinary people usually mean by “consciousness”, is meta. But simple first-person perspective is no more meta than third-person is.

No, but it is usually implied by it. — bongo fury

Which direction do you mean that implication to go? Eliminativists are usually physicalists, sure, but it’s quite a stretch to say physicalists are usually eliminativists. More often they seem to be emergentists, because nobody wants to deny the reality of their own first-person phenomenal experience unless they’ve got a serious philosophical axe to grind.

That person is not providing any answer at all to the question of phenomenal consciousness.

— Pfhorrest

For someone who has defined that question in metaphysical terms, perhaps not. — bongo fury

You’re not clear here, but I think you’re missing something definitional. Phenomenal consciousness is defined as the having of first-person experiences. It’s what people are asking about when you suppose someone has made something that acts exactly like a human being and they ask “But does it have the same experience as a human being or does it just act like it does?” You can say “no”, because nothing has such experience, or say either “no” or “yes” and explain what is happening that does or does not give rise to that in this particular thing but not always in all things (some explanation not about the behavior of it, because that’s already explained and not what they’re asking about), or you can say “yes” because everything has one, so everything that’s like a human has one like a human.We don’t know if they think there is no such thing,

— Pfhorrest

Ditto. — bongo fury

What? You’re not making any sense.

if it somehow emerges from nothing

— Pfhorrest

Remember, it doesn't have to be a substance: a physical goo or a metaphysical woo. — bongo fury

I never implied it was. This is a non-sequitur. -

Is inaction morally wrong?The point is that if you are not doing anything (“doing nothing”), then you are not doing anything that could be wrong.

Bad things may still happen, but there is a difference between good or bad outcomes and right or wrong actions. A right action can’t be one that causes a bad outcome, but bad outcomes can nevertheless happen despite nobody doing anything wrong. -

Is inaction morally wrong?There’s nothing better than heaven. But a ham sandwich is better than nothing. Therefore a ham sandwich is better than heaven?

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?Ok, so "first person perspective" wasn't some innocuous physical concept to do with frames of reference. — bongo fury

I, as a panpsychism, think it is.

It’s only emergentism that makes it out to be anything metaphysically weird. The panpsycist, in taking “phenomenal consciousness” to just be the boring ordinary having of a first-person experience, is free to also be a physicalist, because they’re not invoking anything in addition to physical stuff, just a different perspective on that physical stuff.

Physicalism is not identical to eliminativism.

But what about the "weaker" of this species, who is either functionalist or has some other (e.g. Pantagruel's "systems" or my "symbolic competence") explanation for the emergence, which doesn't at all require that what emerges is anything but an aspect of material behaviour? — bongo fury

That person is not providing any answer at all to the question of phenomenal consciousness. We don’t know if they think there is no such thing, if it somehow emerges from nothing when behavior does the right thing, or if it was always there and just gets refined along with behavior. -

Surreal Numbers. Eh?Those diagrams make me think of a way of visualizing transfinite numbers I’d thought of before, which I realize now could also be used to visualize infinite’s number.

The transfinite visualization is to imagine the real number line projected sort of logarithmically, so that on the left side you have zero and one the normal distance away from each other, but then the numbers get closer and closer the further right you go until at some finite distance right they “reach infinity”; then you put omega there, omega plus one a single unit right of that, and then repeat the whole logarithmic acceleration until twice omega is twice as far right as omega, then repeat that again. Possibly take that whole new transfinite number line and project it logarithmically the same way to reach even bigger transfinite numbers even faster.

For the infinitesimals, do the same thing, except each “omega” is instead a real number, and the logarithmically projected numbers that asymptotically approach each real number are infinitesimals. -

How to live with hard determinismYou are defining “free will” as freedom from determinism. If you don’t define it that way, you don’t have that problem.

-

How to live with hard determinismThat makes you a compatibilist. Can you tell me how that's possible? — TheMadFool

I think I just did. If “free will” doesn’t mean “free from determinism”, then determinism can be true and people can still have free will. Basically, the question of whether or not we are determined is a different question from whether or not we have free will, so their answers don’t have to correlate any specific way. -

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?And this perspective was already on the physicist's menu, or not? — bongo fury

It depends on the physicist’s philosophical views. If he’s an eliminativist then no, he denies that there is such a thing. If he’s an emergentist then yes, but now he’s got a tricky question to answer as to how the other third-person physical behaviors of things that he normally studies spontaneously generate a first-person phenomenal experience in special circumstances. If he’s a panpsychist, then yes, and there’s nothing special to explain because things having a first-person phenomenal experience is a normal thing not in need of any special explanation. -

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?If an object has no functional role of its own, how is it proposed that it could be attended by mental states (even if limited). A sock has no inherent functionality, its function is derived. — Graeme M

Everything has a function, in the sense meant by functionalism, which is different from the sense you seem to mean. A function in the sense that it responds to inputs with some output: if you do something to it, it does something in response. The function of a sock or a rock is very trivial, but it still has one. Imagine for clarity that you were programming a simulation and you had to code what such a virtual object does in response to other events in the virtual world: you have to code in that the rock moves in response to being pushed, for example. That’s a kind of functionality. -

Natural RightsWell, I don't think a non-legal right necessarily exists where a duty exists, either, so I'm afraid we still disagree. — Ciceronianus the White

That’s still the wrong way around. I’m not saying a right necessarily exists where a duty exists, but that a duty necessarily exists where a (claim) right exists, and those duties constitute the entirety of those rights: to have a (claim) right just is for someone else to have a duty to you.

This is independent of whether we mean legal or moral rights or duties. Google “Hohfeldian analysis”. -

How to live with hard determinismour behavior is compatible with both the existence and the nonexistence of free will — TheMadFool

That suggests that that notion of “free will” is not a useful one, and probably not what ordinary people mean, what the term was coined to refer to. Look instead to paradigmatic cases where ordinary people say something was or wasn’t done of someone’s free will, and figure out what’s different between those cases. I guarantee it’s not whether or not the universe was deterministic, and consequently ordinary people don’t really mean “free from determinism” when they say “free will” — and any sense of “free will” that is taken to mean that surely is irrelevant to actual human life. -

God given rights. Do you really have any?I think you read Hot Potato backwards; he’s against the 1500s attitude and applauding me for also being against it.

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?You all miss the point completely.

Nobody has any problem with the behavior of human brains (weakly) emerging from the behavior of their constituents in the way that heat (weakly) emerges from the motion of particles.

What panpsychism is about is when people ask "Okay that accounts for the behavior of people and their brains but where in any of this emergence of complex behaviors did phenomenal experience start happening and why?"

Then you can either give some answer to where that completely different metaphysical thing started happening (and how do you do that exactly?), or else you say "it didn't start happening, because nothing else besides the behavior happens", or else you say "it didn't start happening, because it was always happening to a trivial degree at the fundamental level, and all that emerged was a more complex aggregate of that trivial fundamental thing." -

Natural RightsWell, it is conceivable that in principle one could have a duty that is not toward another person, in which case one would have a duty while nobody had any corresponding right. But the converse is not true: if someone has a (claim) right, that just means that somebody has a duty to them.

-

Leibniz, Zeno, and Free WillIf I were to take your side and believe that reason is causally potent, I would have to say that no matter how good an argument for free will, we're actually not free because reason is involved.

It seems that reason is, well, not like the "others" in that being under its influence or being guided by it doesn't constitute a loss of freedom. — TheMadFool

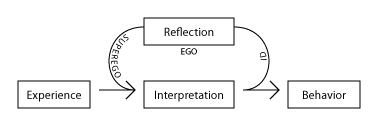

The only reason (no pun intended) that reason is different is that the ordinary cases we refer to when we talking about someone acting "of their own free will" are cases where they did something because they thought (reasoned) it was the best course of action and not because something else contrary to that made them. Basically, because we identify ourselves with our reason, for good reason I think: the ego, the "I" of a self-aware, self-controlled, sapient being, is the middle part of the loop of reflexivity:

Free will is not having our behaviors be uncaused entirely, but having them be caused by that reflexive process that we identify with, rather than caused by something else. -

How to live with hard determinismThe "hard" in "hard determinism" signals that it is a view that holds determinism to be both true and incompatible with free will. The hard determinist definitionally thinks that nobody has any meaningful choice. If someone thinks that determinism is true, but that people still have a meaningful choice, that is definitionally not hard determinism, even though it is still a deterministic worldview. People used to call it "soft determinism", but nowadays that is just subsumed under "compatibilism".

-

What problem does panpsychism aim to address?Heat is only weakly emergent. Heat is an aggregate of ordinary motion. If you model the motion of all the particles in a physical system, you model all the thermodynamic properties of that system too. Heat is only emergent in the sense that you don't have to model things at the molecular level to get heat -- you can just model the aggregate property and ignore all that finer detail.

Phenomenal consciousness is supposed to be the kind of thing where, even if you modeled the physical aspects of a human being in their entirety, you still wouldn't necessarily have modeled that. It's not supposed to be some kind of aggregate of physical behaviors, but something entirely besides the physical behaviors.

There are only three options with regards to that kind of thing:

#1: Nothing has it. Not even us. We are all philosophical zombies. Nobody actually has any first-person experiences. Third-person observable behavior is all there is to a human being. (This is eliminativism.)

#2: Only some things have it. Even though it's not an aggregate of physical behaviors, it spontaneously starts happening out of nowhere wherever certain patterns of physical behaviors happen. Because reasons. (This is emergentism).

#3: Everything has it, just having it at all is trivial and fundamental, and it's only when aggregates of equally trivial fundamental physical behaviors build up into complex behaviors that aggregates of this trivial first-person experience simultaneously build up into complex experiences. (This is panpsychism). -

How to live with hard determinismDennett is famously not a hard determinist but a compatibilist. That's the whole point of "Elbow Room".

-

How to live with hard determinismI would think that for a hard determinist, there would be no question about how to live your life. You’ll just live it however you live it, because it’s not like you have a choice.

Alternative, maybe determinism doesn’t exclude the possibility of choice, but if you agree then you’re not a hard determinist, you’re some variety of compatibilist. -

Let’s chat about the atheist religion.following an ideology is a prerequisite of religion — Gnostic Christian Bishop

Necessity is not sufficiency.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum