Comments

-

The stupidity of contemporary metaethicsEthical naturalism is right about a natural ontology, but it wrongly assumes ethical propositions are descriptive cognitive propositions like non-ethical propositions are.

Ethical non-naturalism is right to reject that whole bag, but it’s wrong to identify the problem as the “natural” part.

Ethical non-cognitivism (of which expressivism is the usual species) is right to see that both of those have a common flaw, but wrongly identifies that flaw as cognitivism.

The correct solution is non-descriptivism, which can still be cognitivist in its moral semantics, and naturalist in its ontology, while dodging the problems of all three of the above. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleDon't be ridiculous. Everyone is answering moral questions, no thanks to your theory. — SophistiCat

And to the extent that they are genuinely trying to answer those questions and not throwing up their hands and saying "because ___ said so!" or "it's all just opinions anyway!", they're doing things as my theory recommends. I'm not saying that my theory is an entirely new thing completely unlike anything anyone else has ever done. It's mostly just taking bits of other approaches and putting them together, leaving out any bits of those other approaches that (if I'm right, and if they were applied consistently) would end up at one of those two thought-terminating cliches above.

You're asking where my views "find purchase". That reduction of the particular things I disagree with to just giving up is where that happens. If I'm right about all the inferences between things, of course. But that -- "don't just give up" -- is what I'm ultimately appealing to to support everything else.

No, I'm well aware of the fact that you're talking about a dynamic world adapting to satisfy people's changing appetites in real time. I'm saying that such an aim is impossible. the fact that you're prepared to update your world as people's appetites change does not have any bearing on the problem of people's appetites changing faster than you can update your 'ideal world' to accommodate the change. If your 'ideal world' is permanently several years behind the appetites it is supposed to satisfy then what exactly is its purpose? — Isaac

This still sounds like you think like my proposal is that we re-run through the whole elaborate process of "peer review" every time anyone's appetites change, to come up with an updated picture of exactly how the world will be that will then be forced on everyone -- too late, now that everyone's appetites have changed again. That's not what I'm proposing. As I've already said several times before, the "dynamic" solution to the problem I'm talking about is a liberal/libertarian one: let everyone control their own surroundings in real time. No long roundabout multi-year process required for those constant day-to-day fluctuations.

you're not an unprecedented genius — Isaac

You're the one putting that claim in my mouth, not me. I've tried to be very clear that my views are mostly just a combination of other already well-known views, minus the parts of those that are usually objected to, usually substituting those parts with parts of other views instead, but without importing the parts of those other views that are usually objected to, etc.

This altruistic hedonism part of my view is basically just the normal ends of utilitarianism, there's nothing new there. But there's several objections to utilitarianism, including the question of on what grounds we can claim that minimizing suffering / maximizing pleasure is good, and the objection about the ends justifying the means. So I give a pragmatic argument for the first of those that's grounded in something like a secularized version of Pascal's Wager; and for the second thing I separate questions about means and questions about ends in the same way we normally separate epistemology and ontology, and while I agree with utilitarianism about the ends, I don't claim that that justifies just any means, and instead give a deontological account of the acceptable means to those ends, modeled after a falsificationist epistemology, which of course is nothing new of my own, though I do give what so far as I know is a novel argument for it again grounded in that secularized version of Pascal's Wager.

The only reason I'm even putting forth these views myself is because I am unaware of anyone having put forth quite this combination of these facets of these views like this before, after having looked for someone who did. I know that pretty much all of the parts are unoriginal, but I've not seen anyone put them all together like this.

If someone has, and I just don't know, I'm hoping to find out about that. (Like with my meta-ethics: I hadn't heard about anyone combining non-descriptivism with cognitivism, in a way almost but not quite like Hare's universal prescriptivism; but I eventually found out that there had been a paper on just that, inspired by Hare, published just shortly before my philosophy education, which is why it wasn't in my curriculum yet).

And if nobody has, then hey, maybe this is an idea worth sharing, and not just keeping to myself.

You seem to want to force upon me a dichotomy of either me saying nothing new and so nothing worth saying, or else me arrogantly thinking I'm some kind of unprecedented genius because (so far as I can tell) I've had a new idea. What would be an acceptable (to you) thing to say somewhere like this, if neither "I (dis)like this old idea" or "I think this might be a new idea" is allowable? -

Peer review as a model for anarchismYet again, for some reason, assuming everyone but you is an idiot waiting to be instructed. — Isaac

Yet again assuming things about my character unreflective of anything I've said.

How do you suppose those people arrived at what they 'already thought'? we've a sense of empathy from as young as six month's old. We dedicated that overwhelming majority of our brains to predicting the behaviour of others and how our behaviour will affect them based on that empathy (together with a whole host of other sources). By adulthood people have spent more hours studying other people, putting themselves in their shoes, predicting what the results might be, than any other subject. They've talked about these things with friends, family, colleagues... They've read books with heroes and villains, watched films, plays, songs...

They've all come up with much the same answers when it comes to the obvious stuff, and no law is ever going to tell people to kill innocents, they just won't do it.

But some stuff, the more complex stuff, people's research has yielded different answers, and the rightness or wrongness of those answers can't be tested because a lot of the time it's about consequences too complex to actually follow (like predicting the weather by following air molecules, accurate but impossible). — Isaac

People come up with folk beliefs about what is real all the time too, and broadly agree on the obvious things, yet disagree on less-obvious things. Does that mean we shouldn't do natural sciences, but instead just poll people on their beliefs? Yes yes complexity I get it... so we shouldn't do meteorology then? Or, we should do meteorology by polling people on what they think the weather will be like, because there's no way we could possibly do any better than that?

rarely — Pfhorrest

And I can't think of a single person who doesn't already think that. — Isaac

The legal systems we have in place now explicitly don't think that. You can argue in your defense that you didn't do the thing, or that the thing you did is not the thing the law is against, but "I did the thing the law is against, but it's not wrong to do that" is a non-starter. You don't even get a chance to argue that the law is incorrect.

Neither. It's about uncertainty in complex systems. The more nodes in the system the more exponentially complex it becomes. small hunter-gatherer tribes have fewer nodes and so more predictable feedback loops. Larger societies have exponentially more complex networks making feedback practically impossible to predict. Imagine the difference in a game of Chinese whispers with a group of ten compared to a group of ten thousand. How ell could you predict the final word in each case? — Isaac

What does this have to do with (in)equality? Societies are bigger now, so we must have authority (and thus inequality) to make them predictabl(y bad)? -

Peer review as a model for anarchismThat doesn't sound like a description of any legislative process I've ever heard of. That sounds like a description of how some folk ideas about morality might develop. It also doesn't sound quite like what I'm advocating in some rather important ways.

In actual legislative processes that we have today, some set of people (depending on the legal structure in question) voice their judgements on the basis of whatever such folk ideas about morality they might or might not have, and then through some process (depending on the legal structure in questions) some of those judgements "win", and everyone's behavior must conform to those.

That would be like if we wrote textbooks by just asking some set of people (differing country-by-country on who exactly) what they thought was real, and then through some process (differing by country) some such pre-formed folk judgement about what is real got written down in the textbooks, and taught to everybody.

Where in there (in either case) was any actual systematic research and consensus-building done? You just asked some people what they already thought and then somehow or another picked winners on the question of who thought right. There's no credence paid to the possibility that everybody was wrong to begin with and they might need to come up with some new ideas if they want any hope of becoming right.

That's where the important differences between your description and my method come up too:

Being creatures with empathy and a co-operative social structure, we also strive to make the world such that it fits what we think will satisfy those other we live with, both now and in the future. — Isaac

We naturally strive to accommodate those who we care about, but rarely explicitly codify in our processes that we should accommodate everyone, as I'm advocating.

cultural practices become a shortcut to the process of working those out — Isaac

And when those cultural practices are entrenched, in law or even just in tradition, we're loath to make exceptions of revisions to them when they fail to work. Whereas I'm advocating that if a "law" as written produces a demonstrably bad result, that alone is reason to change the law. The law is just a shortcut to predict what's likely to yield a good result, the way theories are shortcuts to predict observations, but if either fails to do so, we must change however necessary to accomplish the things our tools are mere shortcuts toward.

The less dynamic the environment, the less interactions whose feedback need to be accounted for, the less chaotic that probability space is. Hence the many thousands of years of relatively egalitarian societies devolving into the mess we have now. — Isaac

Are you suggesting that inequality produces good outcomes more reliably? Or just that it lets us more accurately predict outcomes -- by forcing them to be bad? I understand your first sentence fine, but I don't see the connection to the second. Egalitarian, and libertarian, societies where everyone is equally free, allow for more dynamic response to people's changing target valences, so should allow for everyone to satisfy themselves more reliably.

In any case, it seems like you're focusing entirely on the first part of this political philosophy to the neglect of the rest, which (in the aforementioned egalitarian and libertarian fashion) should negate a lot of the problems with what you seem to assume is the overall project. I'm not at all advocating that we should prescribe one exact static form of life for everyone. Quite the opposite, I'm advocating radical freedom and equality compared to any society in the status quo today. The part you're talking about is basically my account of how to compile reliable advice on how to avoid conflicts in such a free and equal society, to use both preemptively to prevent such conflicts from occurring, and in the assignment of culpability if such conflicts occur anyway. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWell, all you've told me so far is "if I am right, then I am right." I still don't have any idea of where your moral philosophy gets its purchase. — SophistiCat

No, I've said that if I am right, then every difference from to my view, if applied consistently, is tantamount to "just give up" (on answering moral questions). So, presuming one would care to answer moral questions if it should turn out to be possible, one must (if I am right) act in a way that tacitly assumes the premises I start from, and therefore (on pain of inconsistency) accept all that's logically implied by them.

That's just the big picture overview. If you want the full argument, I've done a huge series of threads on it here over the past year. Foundational principles, semantics, ends, agents, means, and institutes, for your reference.

To counter that you'd have to show that your system is, in fact, possible to apply. A system which relies, for its execution, on facts which are impossible to obtain with sufficient accuracy to yield results better than guesswork is not applicable. This third-party data on which your system relies changes too rapidly with too strong a feedback from the system itself for any scientific-like investigation to yield its answers in time for their enaction to bring about the desired result. Hence your system is not one that can be applied by humans. — Isaac

You are again assuming that I'm aiming to create a static world that permanently satisfies everyone exactly how it is, rather than a dynamic world that adapts to satisfy people's changing appetites in real time.

That's where your system fails. What's the point in deciding that Xs are 'good ends' if later analysis of how to achieve those ends shows us that doing so is impossible? We have a choice here, we can set up our 'good ends' such that they are practically achievable, or we can set them up such that they are entirely useless at any pragmatic level. If you ignore the issues with method, you are just building pointless sky castles. Ethics is about real action among real humans. — Isaac

This sounds like exactly the thinking I was just charitable enough to assume Baker wasn't engaging in, when I responded to him:

Even if we can't get all the way there, that's no reason to not go as far as we can. You are the one who seems to be saying "we can't possibly get all the way there, so let's not try". Would you have us pick some more accomplishable goal, try to get there, and then if we do get there, just stop trying to improve? Or wouldn't you have us keep trying to improve as much as we can? The latter is what I advocate, and I wouldn't have even thought it needed to be specified if you hadn't implied that you think to the contrary. All I've specified is what direction "improvement" is. — Pfhorrest

I'm just saying that we should be trying to reduce everyone's suffering as much as we can manage -- that perfection would be total elimination of all suffering, that's the ultimate shoot-for-the-moon goal, and the closer we can get to attaining that, the better. We can certainly sometimes reduce some suffering. That's a step in the right direction on my account, and not to be discounted just because it didn't eliminate all suffering forever. Would you at some point say "that's enough suffering eliminated, we can stop now", and just give up on even attempting to get rid of even more? Where is that line to be drawn, and why?

The whole method of verifying people's hedonic experiences that you're contesting to vehemently is just a way to tell reliably if something consistently causes certain types of people to suffer in certain contexts, so that we can know to stop doing that. It doesn't need to tell us exactly what we must do; outside of those known-bad things, anything is permissible.

This is exactly analogous to falsificationism and in my overall system is a direct application of the very same principles: we're not even trying to pick out exactly what the right thing is -- whether "right" here means "true" or "good" -- because that would be impossible. We're just trying to narrow down on the range of possibilities wherein it might still be.

No, That is possible to predict, already has been predicted, and is something no-one but a psychopath generally struggles with. So no new method is required to assist with it. — Isaac

And yet we're still discovering more and more things about that as time marches on, recognizing the different challenges that different kinds of people have and adapting our social world to accommodate those differences. How are we discovering these things? Basically by "emic" sociology: we're paying attention to the first-person lived experiences of different people, and accounting for those different perspectives in our models of what is good and bad. Just like I'm advocating. Yet some of these recent adaptations are the things met with the fiercest social and political resistance. I guess just half of everyone are sociopaths? Or, maybe, we're just not all in good habits regarding updating our moral views? Maybe someone should advocate those kinds of habits some more, try to get everyone on board with that program...

You've just completely ignored the argument I've already given against the pragmatism of this. I'll just repeat it, in case you're confused into thinking that ignoring it makes it go away. — Isaac

I don't know where the miscommunication is happening here, because the part you repeated sounds like it's arguing against trying to come up with a static, unchanging world that forever satisfies the appetites of everyone, when what I wrote that you're responding to is an explicit denial that that's what I'm trying to do. I'm not disputing that the thing you say is impossible is impossible; I'm disputing that I'm advocating that impossible thing.

See a few paragraphs up ("The whole method of..." and "This is exactly analogous...") for elaboration on how what I'm advocating is different from that. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleOf course we do. 'Bad' is not synonymous with 'feels bad currently'. So in order to know whether first person experiences of suffering are 'badly we need to know something of the future consequences of first person suffering. These are not given as part of the first person experience but rather as results of empirical investigations. — Isaac

I didn't say anything about only considering present first-person experiences. Future suffering or enjoyment is still a first-person experience. True, we can't know the relationship between present and future experiences entirely in the first person, we have to do a third-person study of the world to establish that, but that's once again a question of particular means, not of general ends, and so not something I'm saying anything about here when doing philosophy, but a subject for some logically posterior scientific investigation.

Right. And any moral theory (of your negative hedonistic type) is a means of reducing suffering. If you start any proposition with "One ought to..." you're talking about a method, not simply a logical fact. — Isaac

This whole paragraph seems confused. The part of moral theory we're discussing here is deciding on what are good ends. That's not in itself a means to achieving those ends, it's just deciding what ends to try to achieve. How to achieve them is a separate, later question. And "method or logical fact" is a strange and false dichotomy. The dichotomy here is between ends and means: a means is a method, sure, but an end isn't just a "logical fact", whatever you mean by that.

What you think you're doing is immaterial to issue. — Isaac

So you get to tell me what my views are, and I don't get to clarify that what you think I'm saying or doing isn't actually what I'm trying to say or do?

For someone who hates pretense as much as you say you do, you sure seem to practice it a lot. (Projecting much?)

No. You responded as if to a suggestion that we could not achieve perfection in our predictions. That's not the issue I raised. I didn't say "We shan't be able to get it perfect", I said we shan't be able to do it at all. — Isaac

You're taking too much emphasis on the "perfect" part, unless you want to deny that even something so vague as "certain kinds of people in certain contexts will tend to find certain things pleasant and certain other things unpleasant" is impossible to predict, which it doesn't sound like you mean in your clarification.

The intended target of emphasis was on the "predict" part, and how that relates to static vs dynamic solutions to the problem of satisfying all appetites. I've already said it but I'll say it again: I'm not suggesting that we have to make the world one exact unchanging way that will make everyone satisfied forever, and so figure out exactly what exact unchanging static state of the world that would be. Just that we have to (do our best to) ensure that the world and people's target valences always align, which can (and probably would best) be done in a dynamic way, enabling people to adjust the part of the world around them to satisfy their appetites in real time.

The problem with idealistic ideologies like yours is that they are an all-or-nothing, now-or-never kind of deal. Anything that is less than the perfect application of an idealistic ideology is still a complete failure. — baker

I just can't comprehend how you could say that in response to this:

doing anything closer to it is still better than doing things farther from it (IMO, of course), even if it does turn out that we're so irreparably flawed that we'll never do it perfectly. We definitely can apply my methodology at least sometimes, at least to some degree, and that's fine enough for me. — Pfhorrest

I'm explicitly saying not to make perfect the enemy of good. Do whatever we can, and even if that's not doing it all, that's still better than doing nothing. All I've laid out is what direction "doing it all" lies in, so that we know what we're trying to get closer to. Even if we can't get all the way there, that's no reason to not go as far as we can. You are the one who seems to be saying "we can't possibly get all the way there, so let's not try". Would you have us pick some more accomplishable goal, try to get there, and then if we do get there, just stop trying to improve? Or wouldn't you have us keep trying to improve as much as we can? The latter is what I advocate, and I wouldn't have even thought it needed to be specified if you hadn't implied that you think to the contrary. All I've specified is what direction "improvement" is.

because of your commitment to equality, will have to value their judgment — baker

Commitment to equally valuing everyone's experiences is not the same as equally valuing everyone's judgements.

I've said this a lot before to clarify the difference: in doing physical sciences, we absolutely do not just take a poll on what people believe. Nevertheless, every replicable observation counts. Observations are a kind of experience, and beliefs are a kind of judgement. That someone disbelieves something is no evidence against it at all, but any replicable observation to the contrary is.

Define "suffering".

— baker

A phenomenal experience with negative world-to-mind fit. — Pfhorrest

I don't understand what this means.

What is a "negative world-to-mind fit"? — baker

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Direction_of_fit -

Peer review as a model for anarchismYes, it was the second half that I'm asking about. The "recognize that process and practice it intentionally" bit. — Isaac

It's likely that someone somewhere has recognized and practiced that process, because it's unlikely that any thought is ever completely new; but we as a civilization (any civilization, or the global civilization) sure don't seem to be recognizing and practicing it in the political sphere right now. If you think the ordinary legislative processes in use today resemble that process, I'd appreciate if you spelled that resemblance out, because I really don't see it.

Who is "we"? — baker

Humanity as a whole. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleUnstructured sets don't have such relational properties. — SophistiCat

Propositions have logical relations to each other whether or not the person assenting to all of them is aware of that. The process of argumentation is all about highlighting such relations that had previously been overlooked. If they hadn't been overlooked then there wouldn't be anything to argue about.

So what is philosophically right about your moral theory, as opposed to others, besides its being your theory? — SophistiCat

If all the inferences making up my theory are correct, what makes it right is that to do otherwise ends up implying merely giving up on trying to answer moral questions, in one way or another; so every attempt at answering moral questions is at least poorly or halfheartedly doing the same things I advocate, and what I advocate is to do what's already being done some and working some, just better and more consistently, and avoid altogether the parts that, if people were consistent about them, would conclude with just giving up.

FWIW that is the same way that I justify critical empirical realism, i.e. the scientific method. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI'm saying that the 'pain' a doctor deals with is psycho-physiological and responds to medicines based on it's psycho-physiological properties. Those properties are facts of biology and psychology.

If you claim, as a philosopher, to be dealing with the reduction of 'suffering' you're either dealing with something entirely different, or the subject of your enquiry is a physiological event with biological properties. — Isaac

You understand the difference between first-person experience of mental phenomena and third-person observation of the physical processes correlated with (and [rightly IMO] assumed to cause) those mental phenomena, right?

I'm saying that philosophy only needs to deal with suffering as a first-person experience: we don't need to know anything about brains to discuss whether or not it is the case that suffering and suffering alone (as a kind of experience, in the first person) is intrinsically a bad state of affairs.

But of course we need to know about brains to properly discuss how to reduce suffering, since it turns out upon third person observation of the physical world that the experience of suffering is a product of brain function.

The first is a philosophical matter, the latter is a scientific matter. You'll find that in pretty much all of my philosophical views, the philosophy is just laying the groundwork for why and how to go do a science of some kind, rather than some ineffectual non-science that will at best yield non-answers.

The point I'm arguing, which you've failed to answer is quite clearly written...

You can say what the answer was yesterday, but by the time you've worked out what the answer is today it's already not the answer any more. — Isaac — Isaac

I directly responded to that, immediately after the bit you quoted:

I'm absolutely not saying that we need to be able to predict perfectly exactly what everyone's target valence will be so as to preemptively prepare a static, unchanging world that will perfectly satisfy everyone's target valences. — Pfhorrest

I'm simply not advocating that we should aim to do the thing you say we can't do, so there's no problem there. You're just assuming that I mean that, even after I've clarified that I don't, which as usual just seems like a purposefully uncharitable reading. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismWhat on earth makes you think all that hasn't already happened in our long history of social interaction. — Isaac

I'm not contesting that something like this has already been happening over the history of civilization, and that through it we've slowly made some moral progress, but I'm advocating like Bacon et al that we recognize that process and practice it intentionally, instead of the mess of baseless authoritarianism that passes for governance today. — Pfhorrest -

What's your ontology?I prefer the not so easy question: what is necessarily not there? — 180 Proof

:up:

My ontology is likewise mostly negative: not so much about the kinds of things that there are, but about the kinds of things it wouldn't make any sense for there to be -- things that make no experiential difference in the world, or things that are simultaneously one way and also a contrary but equally real way depending on who you ask -- with the kinds of things there are being something or another in the complementary set to that, to be answered more specifically by science rather than philosophy.

I do have some further thoughts on how to think about the relationship between something being, something doing, something being experienced, something being done-unto, and something experiencing, all in terms of function, but that's not really a question about which kinds of things do or don't exist, just what it means to exist at all. -

Guest Speaker: David Pearce - Member Discussion ThreadYeah I can see how it fits so well with a Protestant work ethic, and I wouldn't be radically surprised to see it live and common in the real world. I guess I expected a philosophy forum to have a higher percentage of people who aren't mired in that kind of irrationality, though.

-

Peer review as a model for anarchismIf you missed the first few sentences of the OP, this is not something I think is required in general for just anybody to act morally at all, but rather an alternative to the other "behemothic exercises in bureaucracy" that we already have, that currently constitute the legislative processes of governments today.

You hate these analogies but I don't care: it's exactly like I'm saying that instead of the church hierarchy deciding what we're going to tell people is the expert consensus on what is real, we should have scientific peer review. That doesn't mean that every mundane ascertainment of fact carried out by every person in their day-to-day life has to be peer-reviewed, just that our textbooks and such should be based on peer-reviewed research.

And just as there had already been a slow accumulation of knowledge about reality haphazardly following a similar process by the time people like Francis Bacon start advocating that that methodology be recognized and practiced intentionally instead of relying on the mess of baseless authoritarianism that passed for education in their time, so too I'm not contesting that something like this has already been happening over the history of civilization, and that through it we've slowly made some moral progress, but I'm advocating like Bacon et al that we recognize that process and practice it intentionally, instead of the mess of baseless authoritarianism that passes for governance today.

:up: :smile: -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleUilitarianism refers to maximization of 'happiness,' not 'pleasure,' — ernest meyer

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different characterizations, the basic idea behind all of them is to in some sense maximize utility, which is often defined in terms of well-being or related concepts. For instance, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, described utility as "that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness...[or] to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the party whose interest is considered."

[...]

...the seeds of the theory can be found in the hedonists Aristippus and Epicurus, who viewed happiness as the only good...

[...]

...Bentham introduces a method of calculating the value of pleasures and pains, which has come to be known as the hedonic calculus... — Wikipedia on Utilitarianism

Bentham, an ethical hedonist, believed the moral rightness or wrongness of an action to be a function of the amount of pleasure or pain that it produced. — Wikipedia on Hedonic Calculus

Are you suggesting that a doctor is dealing with a different subject when he prescribes pain medicine than you are when you say that 'suffering' is bad and should be avoided? — Isaac

A doctor (rightly IMO) takes as given that reducing pain and suffering is an end goal, and then concerns himself with the means to do so. If someone was self-harming because they thought they morally deserved it, a doctor would see that as a sign of poor mental health, because it's causing them to suffer, and someone who thinks they morally ought to suffer is just wrong (and wrong in a practically harmful way, not just some intellectual disagreement) according to the doctor's presumed end-goal of reducing the patient's suffering.

A doctor would not debate the patient about whether he (or anyone) actually morally deserved to suffer. If he did that, he would no longer be practicing medicine, but philosophy. And though the means of alleviating pain and suffering obviously depend on particular contingent facts, whether or not to aim for that as an end cannot. The doctor qua doctor needs to appeal to contingent facts to achieve the ends of reducing pain and suffering, but the doctor qua philosopher (were he to deign to be such) could not appeal to them to decide whether to take that as an end or not.

The very act of having philosophy will affect your target valences. — Isaac

Sure, and like you just quoted me saying:

Changing the target valences to match the external events is a perfectly fine way of achieving that match — Pfhorrest

I completely acknowledge that certain kinds of philosophies dramatically change one's target valences. A large part of the last thread in this series I have planned is about that: how making "what is the meaning of life?" a philosophically meaningful question to yourself actually generates unpleasant feelings of meaninglessness and vice versa in a vicious cycle, and conversely just feeling pleasantly meaningful (regardless of philosophy) makes that "what is the meaning of life?" type of question seem pointless, and vice versa not caring about that question better allows one to feel pleasantly meaningful.

Your system relies on static data points of hedonic value — Isaac

I literally just said otherwise in my last post, and you even quoted it:

if one were to take a change-the-external-events approach anyway, and the target valences were unpredictable in advance, one obvious strategy would be to enable the subject to better adjust their environment in real time as their target valences change — Pfhorrest

I'm absolutely not saying that we need to be able to predict perfectly exactly what everyone's target valence will be so as to preemptively prepare a static, unchanging world that will perfectly satisfy everyone's target valences. You're reading that static-ness in where I don't mean to imply it. A world that dynamically responds to people's changing target valences is perfectly consistent with my views.

You can only talk about how moral beliefs are interconnected with and depend upon other beliefs after you put them into a theoretical framework. — SophistiCat

Sure, and as I just said:

the breadth or fundamentality I'm talking about here is relative to the sets of intuitions we're discussing — Pfhorrest

We're talking about whatever theoretical framework our interlocutors already have. Whatever beliefs they have, some will be logically related to others, such that changes to some would logically require changes to others, and some changes would require subsequent changes to many more other beliefs than other changes would. The beliefs that, if changed, logically require more changes to other beliefs, are the more fundamental ones, out of whatever set of beliefs the person we're talking to has.

With empirical beliefs we have shared ways of establishing facts and validating theories. We have shared intuitions about the object of study, such as its objectivity and permanence, and that allows us to agree on how to conduct investigations, make progress and settle conflicts. None of that seems to apply to moral beliefs. We certainly share a good deal of our moral beliefs and tendencies, we have shared ways of transmitting and enforcing our morals, but I don't think that we have anything like shared intuitions about metaethics. — SophistiCat

I agree that we have much broader social agreement on the methods of investigating reality than we do on the methods of investigating morality, but that isn't even close to absolute consensus even today, and historically was even further from it, in pre-scientific eras. And if anything we're now once again getting further from social consensus on how to investigate reality lately; there's a reason it's sometimes said that we're living in a "post-truth era" now.

I hope you would agree that those post-truth type of people are epistemically wrong, and that in principle philosophical arguments could be given as to why they're wrong, and why the scientific method is better than their unsorted mess of relativism mixed with dogmatism. And that those arguments hold sound even if it comes to pass that most of the world abandons science and devolves into epistemic chaos.

I view my arguments about ethics as like that. I know there's not broad consensus on them, but that's beside the point, just like it would be beside the point of arguments for science to say that most of the world rejects science. What's philosophically right or wrong, true or false, sound or unsound, etc, is not dependent on how many people accept it.

There are people whose moral beliefs conflict with yours (e.g. they value retribution, regardless of whether it increases your hedonistic metric of good). What are you going to tell them? — SophistiCat

I try to appeal to things that they and I already agree on that are more fundamental (in the sense further clarified just above) in their set of beliefs than the ones we disagree on, and show how those beliefs of theirs that I disagree with are logically contrary to their own more fundamental beliefs. If I can actually convince them of that logical relationship successfully (and that's the big "if" that everything hinges on), they've then got the choice to either reject the belief I'm arguing against, or else reject another belief they already hold much more dearly, that many other of their beliefs depend upon. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI'm aware that in common parlance people take "hedonism" to imply egotism, but that's not the way it's used in philosophy, and hasn't been for thousands of years. Utilitarianism is explicitly a form of hedonism, for example.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleSure; it is good to be happy, but you being happy isn't all there is to being good. (Other people being happy, or generally not suffering, is important too.)

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principlewell, if the definition of 'hedonism' is extended to include 'acting for the greater good' it isnt really hedonism any more, it's virtue instead. — ernest meyer

If the "good" part of "greater good" is people feeling good, then it is. Hedonism isn't egotism.

Also if the only reason you're acting for the greater good (in any sense) is the pleasure you get from it, that's full-on egotistic hedonism. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleI'd be interested to hear the quote you mean, yeah. Thanks. :-)

I think I broadly agree that "acting for the greatest good yields the greatest pleasure", inasmuch as I think a feeling of meaningfulness is one of the highest pleasures (and a feeling of meaninglessness conversely one of the worst kinds of suffering), and helping people is one of the primary ways to cultivate that feeling of meaningfulness (along with teaching, learning, and being helped in turn).

I don't quote follow what you mean that that "totally implodes the entire concept of 'ethical hedonism'", though.

And here I though we might be dealing with something more interesting than the boring old internet messiah. — Isaac

And here we are back to boring old name-calling again. This is the kind of thing that makes me eager to conclude bad faith on your part. Just when it seemed like we were actually having an actual polite conversation and coming to at least a productive sharing of thoughts on a topic (if only the meta-topic of how to conduct a conversation on a philosophy forum), you go and say something confrontational like this again.

This kind of thing really gives an air of you just looking to shoot down anyone who is insufficiently meek in your eyes, anyone who's not afraid to say that they think they might have anything new to contribute. You seem to twist that into arrogance. If I was arrogant I would be trying to get real philosophy journals to publish my thoughts. I know I'm not good enough for that. But I also know that I'm not some phil101 freshman just now thinking about these things for the first time. I'm here looking for people on around my level -- not so far above it like a real journal's peer review panel would be, but not so far below it as your random other place on the internet -- hoping we can all get better together.

Your kind of attitude seems to suggest that you think that if someone's not on the level of a professional academic journal, they shouldn't talk to anyone about their thoughts at all; or, if they do, they should treat everyone they talk to as their betters, do as they're told, and never let themselves entertain the possibility that maybe something that looks like a familiar position they've already examined in detail and rejected might be just that.

My primary objection to your hedonism-as-emprical-data-points approach comes from Bayesian modelling approaches to neuroscience applied to affect states. It was only published a few years ago, and then only in the cognitive science papers. I'm truly impressed that you've read it, understood it, and already rejected it years before it was even published despite having no qualifications in the field at all and there being very few objections to it even now... Truly the work of genius, I'm obviously out of my league even talking to you. — Isaac

You already know this, but of course I haven't studied that; and yet nevertheless I can readily say it's not relevant to a philosophy of ethics (any, not just mine), because philosophy is supposed to be logically prior to empirical data. If you're trying to appeal to empirical data in doing philosophy, what you're doing isn't actually philosophy. I don't claim to be doing psychology, or anything where that sort of research would be relevant, and I would be quite ready to defer to the expertise of someone like you if I was talking about that kind of field, because it's not something in which I have any amount of confidence about my knowledge or abilities. Unlike philosophy.

No doubt that research would be useful in the application of any philosophical method of ethics that cared about affect (like mine does), where specific, contingent, empirical facts matters.

I'm not clear if what you're referring to here is the same thing you were talking about before, about the target valence levels people seek to maintain changing over time and with context, and changing those target valence levels being just as if not more effective at satisfying them than changing the external events they're subjected to. If that is what you're referring to, I've already said before that that all sounds perfectly consistent with my ethical principles, which only care that target valences and those effected by external events match.

Changing the target valences to match the external events is a perfectly fine way of achieving that match, on my account. And if one were to take a change-the-external-events approach anyway, and the target valences were unpredictable in advance, one obvious strategy would be to enable the subject to better adjust their environment in real time as their target valences change, i.e. to grant them more positive liberty. (This is pretty much Mill's utilitarian justification for liberalism, and though I have other more logically prior justifications for it myself, that I just posted a thread about yesterday, Mill's argument works fine to illustrate the compatibility of liberal means with utilitarian ends).

These are all specific means to the ends of minimizing suffering, and in debating those means, empirical psychological research is totally relevant, and I'm happy to defer to your expertise in that matter. But none of that is the kind of thing I've been talking about, so if you think I've been saying anything against it then you've misunderstood me. And I would be happy to take time to clarify myself better, for someone who didn't have such a confrontational, unpleasant attitude as yours; for someone who seemed actually curious just to understand what I think and why, rather than someone who's just looking for any way to shoot down someone he thinks isn't spineless enough. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Pragmatic Compromise

Despite the utopian ideals detailed above, I recognize also that we should not let perfect be the enemy of good, and that the choice should not be between either a perfectly functioning anarchic governmental system or no governmental system at all, leaving in the latter case a power vacuum for the worse kinds of states to spring up unopposed. So it seems reasonable to me that there be in place a slightly-less-ideal, less anarchic, but for the same reason more stable system of governance in place already in case the ideal one should fail; say a social democracy, with the power to enact popularly supported laws and to socially redistribute capital.

It should, wherever possible, allow the ideal anarchic solution to function and stay out of its way, and only step in to ameliorate the gravest failures that would otherwise result in a collapse to something even worse than a democratic state. It can, for instance, resolve otherwise irreconcilable conflicts between the highest levels of the anarchic governmental organizations, and levy progressive taxes to fund a universal stipend to ensure that everyone can afford to subscribe to those organizations.

It may in turn be prudent to have more than just this one tier of such failsafe in place, to ensure that wherever a better system of governance fails, it fails only to the next-best alternative, rather than failing immediately to the worst alternative; say a monarchy elected through direct democratic vote, empowered only to defend the social democracy from outside threats and prevent any inside forces from taking it over from within.

I think that this kind of evolution from state capitalism toward anarcho-socialism is itself a natural progression of rational governments looking to preserve themselves.

Authoritarianism and hierarchy may form the default form of state, given the origins of states from imbalances of power, but such a state will survive longer against the threat of revolution if it asks its subjects what they want of it, and gives them a cut of its takings, naturally inclining such authoritarian, hierarchical states to evolve a layer of social democracy as a means of effectively buying the loyalty of its subjects, or else eventually fall to popular revolution. Such a social democracy can then most easily appease the most people if it simply lets them make their own lifestyle choices instead of telling them how to live, and lets them provide each other with services instead of trying to do so itself, adding a layer of anarchy.

Thus, the lazy selfish authority, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves power toward a social democracy; and a lazy selfish social democracy, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves power toward more anarchic ideals. (This progression is not unlike Karl Marx's historical expectations that feudalism and capitalism would evolve through a phase of state socialism toward an anarchic state of communism).

I don't expect that this process would naturally result in true anarchy on its own, but the trending of better states toward anarchy demonstrates an important principle: anarchy is not the opposite of governance, but the perfection of it, what a government that does more good things that governments should do and fewer bad things that governments shouldn't do tends toward.

A society may thus find itself over time sliding up and down the scale between the worst authoritarian rule and the best anarchy, depending on how well its participants manage to operate within the different possible governmental systems along that scale. Because in the end, it is inherently impossible to force a people to be free. How good of a governmental system a society will support ultimately depends entirely on how much the people of that society genuinely value justice, because that governmental system is made of people, and it is ultimately their collective pursuit of justice that determines how well-governed their society can be.

How exactly to help contribute toward getting enough people to pursue justice, morality, and goodness more generally, is the topic of my next thread. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Socialism

Maintaining a generally level balance of actual power in practice (not just legal power on paper) between all the members of society is of utmost importance to making sure that such an anarchic government can continue to function properly, because if some people have such practical power over others, they have the ability to coerce those others into doing as they say, and so begin to wield effective deontic authority which can then easily grow into a proper state. (Such as if, for example, some people have the means to hire judges who employ more powerful enforcers than others, and so judges in disagreement have no need to appeal upward because one can just unilaterally enforce their decision on the other and their clients, effectively asserting deontic authority).

Because of this interdependence between liberty and equality, anarchic governance requires a socialist economy. This does not mean a command economy, where everything is owned by the government who then directs everyone how to use it; that would obviously be a state, and so not anarchic. "Socialism" means only that the populace cannot be divided into those who own the things that everyone needs to work and survive, called capital, and those who labor upon that capital at the direction of those owners; instead, people should own the things that they use, like their homes and workplaces, and neither own the things that other people need to use, nor need to use things that other people own.

In contrast, such a division of ownership and labor is the proper meaning of the term "capitalism"; not merely a free market, which in turn is just the opposite of a command economy. Anarchism definitionally requires a free market, but in practice it cannot survive alongside capitalism, as the capital owners would merely be the new state. Similarly, socialism cannot in practice survive alongside a state, as whoever leads the state, that controls all the capital, in effect become the new capital owners.

I think that the libertarian deontic principles I have laid out in my earlier thread on that subject, if followed, would result in an economy trending toward a socialist distribution of capital over time, without the need for state intervention to redistribute it, or the the abolishment of all private property to allow people to freely seize it. The principal difference between my principles and other libertarian principles that either abolish private property ("left-libertarianism") or else allow capitalism ("right-libertarianism") is the limit on the power to contract, especially as it regards contracts of rent and interest (collectively "usury", a fee for use).

Right-libertarian theory generally expects that those who possess capital beyond their own needs will sell it to pay for labor (so as to give themselves leisure) from those who possess less capital than they need, who can in turn use that pay to buy the capital they need, and in this way the free trade between owners and laborers will, they suppose, naturally dissolve the class divide and tend to equalize the distribution of ownership and labor. This is commonly referred to as "trickle-down economics".

This observably does not happen in practice, and the reason for that is, I think, the existence of usury, whereby those who own more than they need can instead lend it to those who need more than they own, who then pay for that with the money they are paid for their labor by such owners, but then have to give back the lent property, so that what the owner class pays the worker class generally comes right back to them, more reliably the greater the divide between the classes is.

If instead contracts of usury were powerless, and so such arrangements legally unprotected, those who own more than they need would have no way to benefit from it other than by selling it, and as nobody else who has more than they need would be buying it as an investment vehicle to lend out, they would only be able to sell it to those who need more than they have, on terms that such buyers are able to afford. If they did not agree to sell on such terms, those in the owner class would take a complete loss on their investments in their excess property, so whatever those affordable terms are, it is in the owners' best interest to sell on them rather than not sell at all, and so in the absence of contracts of usury, the ideal free-trade redistribution of property that right-libertarian theory expects would actually happen.

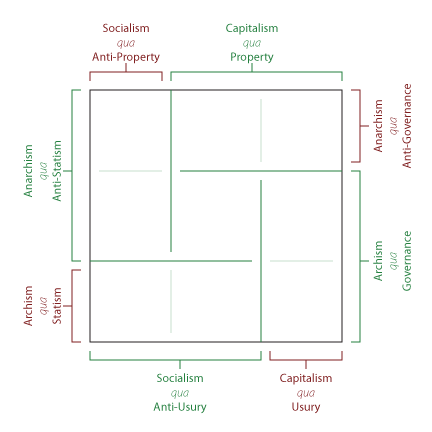

Despite the interdependency of liberty and equality described above, many people try to advocate for anarcho-capitalism or for state socialism, treating liberty and equality as independent, and creating a two-dimensional spectrum of political positions, on which my position can be located. I do not actually advocate for absolute liberty or equality, but rather hold what I view to be a centrist position on both topics, which is technically just barely anarcho-socialist, even though it is far more libertarian and egalitarian then most common political positions.

In one corner of this spectrum are those who advocate for an unlimited state and unlimited capitalism, state capitalists, who include both medieval feudalists (where those who owned land, the productive capital of the time, were the same nobility who constituted the government) and fascists in the sense originally coined by Mussolini (who said it might better have been called "corporativism", consisting as it did of a collusion between big businesses and big government).

Most modern political positions advocate for a more limited state, but still a state, and differ largely on whether capitalism in that limited state should be unlimited (so-called "conservatives" on the right of this spectrum), those who think it should be allowed but limited (so-called "moderates" in the "center" of this small part of the spectrum), and those who think that it should be minimized if not entirely eliminated (so-called "progressives" on the left of this small part of the spectrum). Within the range of various degrees of limited capitalism, there are also those who advocate for a greater state, authoritarians erroneously reckoned as being on the "left" of (this small part of) the spectrum, and those who advocate for a lesser state, libertarians erroneously reckoned as being on the "right" of (this small part of) the spectrum.

In the upper-left corner of that lower-right quadrant where all these positions fall, right on the edge of eliminating the state but not all government and capitalism but not all private property, is my position. In the further outer reaches of the political spectrum, there are those who advocate the abolishment of not only capitalism but of private property, including many of both state socialists and some anarcho-socialists; and those those who advocate eliminating not only the state but all government, including both anarcho-capitalists and some anarcho-socialists. Beyond all them still are a few who advocate for not even allowing self-defense or personal possessions, like some anarcho-pacifists, in the far corner most opposite the state capitalists.

I advocate for a gradual political evolution away from state capitalism along the diagonal toward my position, neither veering too far above it nor to the left of it, even though I want upward and leftward motion, because to imbalance the power of the state against the power of capitalism threatens to veer into state socialism or anarcho-capitalism, both of which, lacking either liberty or equality, I see as completely untenable in the other aspect, as described above, and so tantamount to state capitalism again.

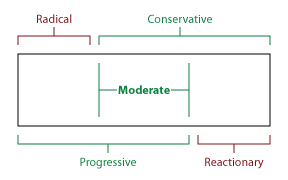

You will note my many qualms about the usage of some terms like "conservative", "moderate", "progressive", "centrist", "left", and "right". I use them above in their more common usage to identify common positions on the spectrum, but I hold that that usage is technically incorrect. These terms originate from the French Revolution, during which supporters of the feudalist status quo of the time sat on the right of their parliament, while those who advocated a change to greater liberty and equality sat on the left. I hold that the proper referents of "left" and "right" are thus the directions away from and toward state capitalism, which forms a diagonal on this spectrum.

The emphasis first and foremost on liberty lead many to treat "left" and "liberal" as synonymous. But because the world powers of the Cold War were (at least nominally) libertarian capitalists of the First World and authoritarian socialists of the Second World, that perpendicular diagonal axis became the new common frame of reference for "left" and "right", leading some to even more generally associate "left" with authoritarianism and "right" with libertarianism. My qualms about what are commonly called "centrists" being called that is that they are only central within that limited quadrant of the spectrum, ignoring how much further away from statism and capitalism it is possible to advocate.

And my qualms about the terms "conservative", "moderate", and "progressive" are that those strictly speaking do not name where on the political spectrum one's ideal political system would fall, but how one approaches change toward their goal, wherever on the spectrum it should be. I hold that the proper referent of "conservative" is someone who is cautious about change, if not completely opposed to it; since the historical trend of change has been away from authority and hierarchy toward liberty and equality, the word has understandable connotations of authority and hierarchy, but does not strictly mean supporters thereof.

Conversely I hold that the proper referent of "progressive" is someone who pushes for some change, if not complete change; since the historical trend has been as above, the word has understandable connotations of liberty and equality, but does not strictly mean supporters thereof. And I hold that the proper referent of "moderate" is someone who is both conservative and progressive, pushing for some change, but cautious change; those progressives who are not moderate, pushing for complete change, are properly called "radicals", and those conservatives who are not moderate, completely opposing all change, are properly called "reactionaries".

I consider myself not only a true centrist on the full spectrum described above, but also a moderate in this sense of conservatively progressive, neither radical nor reactionary. I do not view either change or stasis as inherently superior to the other, for both creation and destruction are kinds of change, and both preservation and suppression are forms of stasis, suppression negating creation just as preservation negates destruction; and it's not even inherently superior to create and preserve than to suppress and destroy, for inferior things can be created or preserved, in the process destroying and suppressing superior things, in which case it would be superior to suppress or destroy those inferior things so as to preserve and create superior ones. I support either change or stasis as they foster superior results, neither unilaterally over the other.

As should hopefully be evident by now, my entire politics is about balancing powers against each other and then diminishing them. (That is precisely why liberty requires equality: inequality is an imbalance of power, and imbalances of power create increases of power.) My ideal stateless government hinges on balancing the powers people have to harm each other, and then diminishing the harm they do to each other. My incremental approach to achieving that hinges on balancing the power of the state against the power of capital and then diminishing both of them. My moderate approach to pushing that agenda hinges on balancing the threat of radicals against the reactionary status quo.

On any of those fronts, whichever side is the weakest in a given context is the one I tentatively support in that context, but only to the extent of balancing it against the other power and then diminishing both. Radical libertarian socialists are useful to widen the Overton window (the popular perception of the range of political options) against the state capitalist status quo, but I don’t actually want them to win a violent revolution and drastically change everything overnight. State-socialist policies are a useful interim hedge against unregulated capitalism, but I don’t actually want that as the end-goal of political evolution. Libertarian capitalists are even useful allies against unchecked abuses of state power, but I don’t actually want their vision to win out either. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Stateless Governance

In the absence of good governance of the general populace, all manner of little proto-states may still spring up, in the form of gangs, warlords, and other strongmen asserting their will over anyone else who is too weak to resist them; and left unchecked, these gangs can easily become actual full-blown states, their personal abuses of power becoming widespread, socially-acceptable injustice, that can appropriate the veneer of deontic authority and force their injustice on others under the guise of justice. Checking the spread of such injustice by challenging it in society is the role of public patrols.

The need for that role would be lessened if more people would actively seek out governance from coaches or judges as I have described them above, but not everyone will seek out their own governance and so some people will continue to spread injustice – and even those who do seek out their own governance may still accidentally spread injustice – and in that event, there need to be public patrols to stand against that. But that then veers awfully close to proposing effectively another state to counter the growth of others.

I think there is perhaps a paradox here, in that a society abhors a power vacuum and so the only way to keep states, institutions claiming deontic authority, at bay, is in effect to have one strong enough to do so already in place. That is essentially the justification Thomas Hobbes gives for supporting absolute monarchy in his Leviathan. But I think there is still hope for liberty, in that not all states are equally authoritarian: some have their laws handed down through strict decisions and hierarchies, while others more democratically decide what they as a society demand from their citizens. I think that the best that we can hope for is a "state", or rather a stateless political or governmental system, that enshrines the principles of anarchism, and is structured in a way consistent with those principles.

Such a system of anarchic governance is somewhat analogous to how, in my thread on the will, I held that "will" in one sense is present in all causation, and neither something beyond causality that imposes itself upon causal chains, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of causes and effects, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of them; and proper will per se requires such configurations and doesn't exist in just any random causal chain, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "will" omnipresent in all causation.

So too, here I hold deontic "authority" to be present in all people, and neither something beyond people that imposes itself upon people, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of people, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of people; and proper governance requires such configurations of people and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of people, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "authority" omnipresent in all people.

The ideal form of such a system of governance would, I think, see the judicial role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come with disputes to be resolved. Those judges then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of the "law books" as described above to make their rulings about what is or isn't just, who in turn turn to authors of legislative secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of legislative primary sources, as described above; while on the other hand the judges turn to coaches and to public patrols to enforce their rulings. When there is a dispute between two people who cannot mutually agree on one judge to resolve their conflict, they can each call upon their own separate judges to step in and resolve the argument between themselves.

If need be, if even the judges cannot reach an agreement between themselves, they can turn to yet another mutually agreed upon judge to resolve the resulting conflict between them, or else escalate further on, until at some point the argument is escalated to some parties who can work out an agreement on the matter between them, or to some mutually agreed upon arbiter who can decide the matter, and in either case then pass the decision back down the chain; unless, in the worse case scenario, an irreconcilable rift in society is discovered, in which case there is no perfect solution regardless of the system of governance we have in place. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Correction

Still aside from that reactive judicial role, I hold that it is also important to have, as most societies already do, more proactive correctional roles, like public patrols; but also, analogous to teachers in the academic sphere, something like life coaches or a business's in-house lawyers.

The role of such a coach, as distinct from a judge, would be to actively guide their clients to intend to do things that are probably good, according to those same collaborative works of legislation referred to by judges, rather than merely to be there to answer questions and resolve disputes as they come up. The coach provides the clients with answers to questions they hadn't even thought to ask yet, and in doing so hopefully helps to prevent disputes from coming up between them in the first place, advising their clients on how to avoid doing things that are likely to get someone else to bring their judges down to bear on them.

To keep this coach role from becoming too authoritative, though, to keep it from becoming mere command of one person by another, I think, like many political philosophers of recent centuries, that it's important to maintain a separation of the governmental roles of executive (of which the coach is one form), judiciary, and legislature; analogous to the separation of teaching, testing, and research outlined in my previous thread on education. A coach should not be advising about laws that they wrote themselves, nor judging their own clients on their compliance with them; and neither should a judge be the author of the laws against which people are judged.

Rather, the laws should be a result of the global legislative process detailed earlier in this thread; accordance with it should be judged by someone in the judicial role described above, someone well-versed in those laws; and the coaching of people to live in accordance with those laws should be done by a separate party, coaching to the same laws as the person who will later judge them, but independent of that judgement.

In this way the coach cannot, upon passing their own judgement, simply rule in favor of those doing things the coach is in favor of and against those doing contrary, but must correctly guide their clients to live in accordance with an independent system of laws that someone else, also independent of the authorship of those laws, will judge them against; and in this way no person involved in governance can exercise unbridled deontic authority over anyone.

Another more familiar role, executive in nature like that of a coach but even more proactive still, is that of public patrols, who rather than guiding only those clients who come to them seeking personal guidance, that being still a reactive process in a way, instead look out over society and step up to act against wrongs where they see them. This begins to veer dangerously close to the public patrol asserting their own deontic authority over others, and to make sure that it does not come to that, this process must wind up turning to an independent, mutually agreed-upon judge figure to settle the resulting argument, by reference to still-more-independent law books that are the product of the global legislative project detailed earlier in this thread.

But I think that it is important to have such public patrols going out and standing up to wrongs done in society, making sure someone stands up to the wrongdoers and they don't just go unchallenged, even as dangerously close to authoritarianism as that might veer, because anarchism is by its very anti-authoritarian nature paradoxically vulnerable to small pockets of deontic authority arising out of the power vacuum, and if that instability goes completely unchecked, it can easily threaten to destroy the anarchic society entirely and collapse it into a new, deontically authoritarian regime; a state in effect, even if not in name. -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Adjudication

Aside from that multi-tiered process of legislation just described to produce an alternative to traditional law books, an entirely different but valuable social role that state governance traditionally serves is that of adjudication. In other words, courts, or judges: powerful and just people who are well-versed in the "authoritative" texts – a state's law books in the traditional role, but the tertiary reference books in this anarchist version – to whom laypeople can come if they have individual questions about what is right or wrong to do, or to whom parties in a dispute about that can come for mediation and adjudication.

The answers given by such a person should not to be taken on their own personal authority, but on the "authority", such as it is, of the entire global process leading to the production of the reference works to which the judge refers for their answers. Such judges should be free to choose the reference works that they find best to use in this process, and individuals or disputing parties coming to them for answers or mediation should be free to choose judges that they find best to use for their purposes, including for the reason of their choice of reference works.

Furthermore, the reference works should not be taken by the judges as infallible, and in each case it should be possible in principle – though increasingly more difficult in practice over time – to successfully challenge the claims of the reference works, and in doing so force a revision to them. In this way the entire process remains technically non-authoritative, with lay people merely choosing to invest those who they judge to be more powerful and just than themselves with a transient semblance of authority to help them better figure out what to do for themselves, or to settle arguments that they cannot settle between themselves. (How to resolve cases where different parties to the same dispute appeal to different judges for mediation is addressed later in this thread.) -

Peer review as a model for anarchismOn Legislation

Just because I am against any such institution being taken as deontically authoritative does not mean that I am against all social institutions seeking to promote justice. I am very much in favor of a widespread, global collaborative process of many individuals sharing their insights into the nature of morality, checking each other's findings, and collating the resulting consensus together into the closest thing to an authoritative understanding of morality that it is possible to create, for the reference of others who have not undertaken such an exhaustive process themselves.

The proviso is simply that that resulting product should always be understood to be a work in progress, always open to question and revision, though it should in time become more and more hardened such that questions to which it does not already have answers become more and more difficult to find, and so large revisions to it become more and more difficult to make.

This is essentially analogous to the process of peer review already widely in use in contemporary academia for the purpose of building knowledge about reality. I am proposing here that a formally similar process, but grounded in the criteria for prescriptive judgement laid out in my earlier thread on teleology rather than the criteria for descriptive judgement laid out in my earlier thread on ontology, can be used to collaboratively compile what amount to law books, rather than textbooks; still fallible, as our judgement cannot help but be, but procedurally narrowing in ever closer to a universal view of justice and morality.

As with the peer review process already laid out in my previous thread on education, this legislative process would also proceed in three broad phases. In the first phase, analogous to the creation of primary sources in a typical academic peer review process, detailed accounts are to be published, not of observations or sensations, but rather of appetites, as defined in my previous threads on teleology and on metaethics. In short, people are to publish that under some specific circumstances someone experienced pain or hunger or some other such thing, detailed in such a way that others can later attempt to replicate those circumstances and see if they experience the same phenomena.

These primary sources can also share the conclusions their authors draw from their experiences – what actions or states of affairs they infer are good or bad on the basis of those experiences of things feeling good or bad – but the detailing of the experiences and the circumstances in which they were had, including the makeup of the people having the experiences (analogous to detailing of instruments used to make observations), is the most important element, so that other people can replicate those circumstances and control for differences between themselves to confirm that in such circumstances such people actually do have such experiences, reliably and repeatably.

Like the replicability of observations in typical academic peer review, this replicability of appetitive experiences is what grounds my proposed "political peer review" in universality, and provides a common ground against which to judge our ideas of what actions or states of affairs are good or bad, right or wrong.

In the second phase of the process, analogous to the compilation of secondary sources in typical academic peer review, groups of other people are to review and comment on the quality of that original research in media such as journals, republishing the original research that they find worthy in the process. Then in the third phase, still others are to gauge the consensus opinion held between those secondary sources on what can somewhat reliably, though of course alway still tentatively, be said about what is moral, and publish those conclusions in more accessible summary works, tertiary sources; essentially, law books.

These reference works are thus the closest things to deontically authoritative texts that are possible, the reasonable substitute for authoritative state law books traditionally taken as capable of defining what is just by fiat alone; though these tertiary sources are not to be taken so authoritatively, but understood as merely the best findings about morality that are as yet available, the strategies that have survived not only the hedonic testing of some individual researcher, but also the heavy criticism of everyone else participating in this endeavor throughout the world. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWhat exactly do you see different about this place to a series of personal blogs? — Isaac

We can ask each other questions, and respond to those. "I don't understand your view, can you clarify?" - "Sure, I'm saying X, as opposed to Y or Z." etc. That's still friendly and cooperative, not trying to win against each other.