Comments

-

On Language and the Meaning of Words“exactly” is ideomatic here, the point is that “wrong” doesn’t bring to mind any specific descriptive indication, but rather a more general imperative prescriptive force.

-

Belief in nothing?Knowledge is a kind of belief.

A guess is also a kind of belief.

A belief is a kind of opinion.

An intention is also a kind of opinion.

Beliefs and intentions are both kinds of thoughts.

Thoughts are kinds of opinions.

Feelings are also kinds of opinions.

Desires and perceptions are kinds of feelings.

You're really not getting some basic things like subset relations and modalities here. -

On Language and the Meaning of WordsEthical discourse seems to me to be about deciding how to describe and (thereby) classify human behaviours, e.g. deciding whether "wrong" denotes this behaviour or that. — bongo fury

What exactly is being described of an action when one decides that "wrong" is an applicable word to it, though? Whatever answer you may give to that, e.g. "causes pain in someone", one can still ask whether or not "is [causing pain, etc] wrong?" and it's not like asking "are bachelors unmarried?"; the answer (yes or no) is not a tautological or contradictory matter of definition, it's an open question. This is precisely the Open-Question Argument. -

Belief in nothing?Thinking or believing is broader than speculating/supposing/guessing. You are trying to pigeonhole every opinion into a blind guess. They aren't, and it isn't necessary for them to be to define the relevant categories.

-

People want to be their own gods. Is that good or evil? The real Original Sin, then and today, to moHaven't read any of this thread so far, but when I see it I keep thinking: Trying to be more godlike is a good thing, if by a god you mean someone all knowing, all powerful, and all good. Trying to learn more, be more able, and be a better person is good. You can't ever achieve all-knowing or all-powerful, but you can an principle get arbitrarily close eventually, and you could in principle (but probably not in practice) become all-good, including being both inerrant (never doing wrong) and at least emotionally invulnerable (never being wronged, by attaining ataraxia, or nirvana, so nothing ever hurts you).

-

Belief in nothing?Whose meaning is correct is just a matter of whose meaning corresponds to the history of usage. It makes no difference as to whether the opinions under discussion are correct or not, so long as we can understand each other about what those are.

You were in agreement so long as when I said “think” I didn’t mean “believe”. It’s clear now that zi obviously do, because to think something about whether or not something exists is to believe something, as I understand the word. (And I’d argue as ordinary English speakers understand it too, but that doesn’t really matter). If you import something else into the meaning of the word “believe”, that’s on you, and not part of what I meant (and I have no idea what more you might mean). -

CoronavirusReally? You find TP in the shops where you live? — Nobeernolife

No, but I find it’s not just (or even mostly) poor people hoarding it. Because they barely have money to buy it with if they can find it. -

CoronavirusI thought they are planning for some sort of temporary universal income scheme to do just that. — Nobeernolife

I had heard talk about that but then this morning when I searched for news of progress there all I saw were plans to bail out large employers rather than the people they employ. I guess TPTB think it’s safer to err on the side of making sure no freeloading poors get a handout than to err on the side of making sure no hardworking people slip through the cracks.

I just hope they take in account that a lot of the people who get that handout will be spending it not for life essentials, but for more unnecessary crap from China. — Nobeernolife

People will spend it on whatever they think is most necessary. Isn’t the whole point of the free market that whatever people freely choose to spend money on is what deserves that money, rather than big government telling people what’s good for them? If you give poor people money they’ll immediately spend it on whatever they judge is the most needed thing (which for most of them, especially in hard times, will be rent and then food), and whoever is best providing that most valued thing will profit the most, just like markets are supposed to do. -

CoronavirusSo apparently the big US financial relief package being worked on this weekend focuses on... bailing out the largest businesses, and I guess hoping some of that money trickles down to the actual people whose lack of money is the cause of those businesses failing.

Why the fuck can’t anybody understand that money flows up, not down, so if you want more economic activity, send money to the bottom. It’s the people at the bottom suddenly losing their access to money that is the cause of this whole crisis, the obvious solution is to just send them money, but, no, instead we need some patchwork of bullshit business bailouts that we hope will indirectly solve the problem. -

On Language and the Meaning of WordsThanks for the typo catches.

I’m not sure I follow the rest of your post, but I’m not meaning at all to demean descriptive speech-acts, or to say that one cannot merely describe without also doing something that else. I mean only to place description as one of several kinds of equally important and complex kinds of speech-acts. Describing is an important thing to do, and one can describe without also doing anything else. But one can also do other important things besides describe, and do them without also describing in the process. -

Belief in nothing?I guess you didn’t understand my disambiguation at all earlier.

Consider, for analogy, thoughts about colors. You can have thoughts about red colors, or thoughts about nonred colors, but those are all thoughts about colors. Call thoughts about colors “coliefs”. You could, instead, have thoughts about something else entirely, not about color at all, and those thoughts would not be “coliefs”. But any thought about colors, whether it’s about red or nonred colors, is a “colief”.

Do I need to spell out the analogy? -

Belief in nothing?No? Honestly I can’t really understand you here.

Having any opinion about the existence status of anything constitutes a belief. You can believe that something exist, or believe that it doesn’t exist, it’s still a belief. -

Belief in nothing?I don’t understand the difference between the two here. The topic of whether or not something exists consists of that thing existing, or not. — Pinprick

You seemed to be considering “thinking that something does not exist” as a different category from “thinking that something exists”. I’m considering the single category of “thinking about whether or not things exist”. Any answer (yes or no) to the question “does x exist?” is a belief. Which answer you give doesn’t make a difference as to whether thinking that answer constitutes a belief or not. -

Belief in nothing?Ok, so you’re claiming that not all thoughts are beliefs, but all thoughts regarding the existence of an object are beliefs. Did I get that right? If so, then it seems that there is something special about existence that causes all thoughts regarding it to be classified as beliefs. What is that special thing? Also, if you’re claiming, and I don’t know that you are, that thoughts about the nonexistence of an object are beliefs, then you’ve contradicted yourself. — Pinprick

I think you misunderstand what I’m saying in two ways.

One is that I am just reporting the function the word “belief” as I understand it as a native English speaker, not making an argument that some things rise (or stoop) to the level of “belief” in some already-agreed-upon sense of the word.

The other is that I’m not saying belief is about thing existing vs them not-existing, but rather it is about the topic of whether or not something exists.

To believe something is to think something about how the world is or is not, about what is real or not, what exists or not, etc. As opposed to, say, thinking something about what is good or bad, what ought or ought not be, etc. Or other kinds of thoughts about different kinds of things. -

Metaphilosophy: Historic PhasesIt occurs to me that the litigious society of ancient Athens was a byproduct of their democracy: because nobody can just pass down unilateral judgement, it is necessary to argue and persuade people to agree. The resemblance of philosophy to Athenian litigation then makes perfect sense as a consequence of the democratization of knowledge: as soon as you stop taking authorities at their word and start questioning everything, you need to argue and persuade people to get consensus on what is true.

I think it’s thus not a coincidence that philosophy emerged from a litigious climate. It’s not something that just happened and didn’t have to. Any critical enterprise of investigation has to end up with at least a broad family resemblance to philosophy as we know it. -

Belief in nothing?What post of mine are you referring to? — Pinprick

The one that I replied to. You can click your own name at the start of my reply and it will take you back to the post I'm replying to. I'll quote the whole exchange here for convenience anyway.

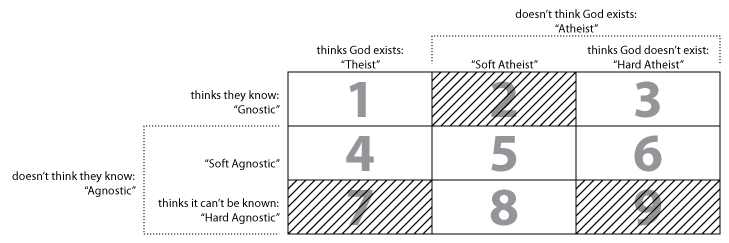

It started with this post where I posted this image:

Then you replied:

Agree 100% with this as long as you aren’t equating “thinks” with “believes.” — Pinprick

I am, because they mean the same thing. To believe something is just to think that it is true, nothing more. — Pfhorrest

Right, but wouldn’t you agree that not all thoughts are beliefs? If so, then the thought “no Gods exist” doesn’t have to be a belief. — Pinprick

I’d say all thoughts to the effect that something exists or not constitute beliefs. There are also thoughts that are not about what does or doesn’t exist, which are not beliefs, but we’re not talking about those here. — Pfhorrest

Ok. What justification can you provide for excluding thoughts about existence? — Pinprick

Excluding them from what? I’m not excluding them from beliefs, I’m limiting beliefs to just them. I think you misread me. — Pfhorrest

I’m asking why thoughts about existence must be beliefs. Why do those types of thoughts warrant the designation of “beliefs” when others do not? — Pinprick

Because... that’s what a belief is? A thought to the effect that the world is such-and-such way. I have no idea what you’re on about here. — Pfhorrest -

On Language and the Meaning of WordsThanks for that feedback! I'm glad you mostly agree.

That is an interesting point of view that I haven't heard before. A kind of quietism about philosophy of language. I don't agree with it, although I see the difficulties and pitfalls you warn of, but I think that we can work around them to a large extent.

I don't know, maybe your assumption that the low-hanging phil 101 fruit is done with is wrong. — Harry Hindu

I'm referring to the six preceding threads in this series, where I discussed really basic broad general principles without focusing on a specific sub-topic of philosophy.

I didn't take time to read the wall of text in your link, but you seem to think that using words only entails making sounds and scribbles. If that were the case, then what separates any sounds or scribble from words?

Any theory of language that doesn't take into account the fact that words are seen and heard (we use our senses to be aware of language use just as we use our senses to be aware of everything else in the environment), and that language-use requires that these scribbles and sounds be seen and heard, not just made, for language to occur. — Harry Hindu

If you didn't read the essay, then I don't know where you get any impression of what I seem to think from, especially that I don't take that into account.

"Push" and "pull" are inappropriate terms to use when describing utterances and questions. It makes it sound like thoughts are moved from one person to another. "Copy" is a more apt term that describes what it going on.

Think of scanning a hard copy of a document and then emailing it to your friend who then prints it out and now has their own hard copy. Not only do you still have the original thought, but you translated your original into a different type of media (paper and ink to electronic) and then your friend receives the electronic form and translates it back to paper and ink. We do the same thing when using language. Our thought is translated into another medium (paper and ink or sound waves) that are then received and translated back into the thought that those scribbles or sounds invoke in the reader/listener. — Harry Hindu

Oh, so you did read it after all.

Anyway, I don't disagree with any of that. The "push" and "pull" are about who is initiating the copying. We actually use those same terms specifically with regards to digital media (or at least we did for a while, the fad about "push media" seems to have died down a lot): "pull media" is the usual kind of internet content where a user goes out and requests something from the source of the media, who then sends it to the user. "Push media" in contrast is media where the initiation happens on the sender's end, more like traditional television, as compared to video-on-demand which is more like usual internet content. Modern things like YouTube seem to blend that a bit, where the user goes out and pulls one thing, but then a bunch of other things get pushed at them too. -

Belief in nothing?No...I do not "believe" I am Frank. I KNOW I AM FRANK. — Frank Apisa

Knowledge is a subset of belief. Everything you know, you believe. -

Belief in nothing?Because... that’s what a belief is? A thought to the effect that the world is such-and-such way. I have no idea what you’re on about here.

-

On Language and the Meaning of WordsShould I just give up on this whole project? Now that the boring low-hanging phil 101 fruit is done with, right as we’re finally start to do some more substantial stuff...

-

CoronavirusThat is good, but only postpones the problems, because it doesn’t get people out of the obligation to pay those months’ rent/mortgage eventually, so when the crisis is over and people get their jobs back and able to be evicted or foreclosed upon again, they’re still months behind on their rent/mortgage and up shit creek if they can’t magically manifest that money from somewhere.

Apparently you can’t read to the end of a sentence, because I already addressed this later in the same sentence you quoted only the beginning of. -

What are the First Principles of Philosophy?I never denied the existence of non-empirical truths, I said an implication of those first principles is that one’s ontology should be empirical realism, i.e. one should not make claims about what exists that are non-empirical or non-realist. We can talk about things besides just what exists or not, though, and those claims are not confined to empiricism or realism by those principles.

-

What are the First Principles of Philosophy?Sure, but these are statements concerning epistemology; what about statements concerning ontology? Is — TheGreatArcanum

Those aren't just statements concerning epistemology. The "no unanswerable questions" one is more ontological than epistemological: a full half of that principle is just equal to realism, and the other half is moral objectivism. The "no unquestionable answers" one is more epistemological, but it has direct implications that are again more ontological: if every answer must be questionable, then no appeals to things that can't be questioned are acceptable, ruling out the supernatural, i.e. the non-empirical. Between those two things you have a robust ontology of empirical realism. And on the moral side of things, the analogue of that, a kind of hedonic moral objectivism. Conversely, the "no unanswerable questions" principle has direct epistemological and deontological implications as well: justificationism would, through Agrippa's Trilemma, lead either to foundationalism or coherentism (which violate the "no unquestionable answers" principle), or else to rejecting all opinions out of hand, violating the "no unanswerable questions" principle, so contra justificationism we have to have a critical rationalist epistemology, and the moral equivalent of that, a liberal deontology (where you're allowed to do what you like until reason can be shown not to, rather than forbidden from doing anything until you can justify that there is a good reason to).

All of those things then have far-reaching implications on things from philosophy of language, art, and mathematics, mind, will, education, governance, and so on. -

CoronavirusSo, what if people are out of work and have not enough to pay rent/ mortgages? — Janus

I'm not sure if you're saying "so what" as in "whatever, no big deal", or if you're asking me what should be done to help in those cases. Your punctuation suggests it's not the former, but I literally already answered the latter at the end of the very post you're responding to:

we could solve the whole financial crisis just by forcing money to flow from where it is concentrated to where it is lacking, from where it will flow back into concentrations again. Like CPR for the economy. — Pfhorrest

The government should just give people money so that they can keep paying for access to the plentiful resources we already have, through the usual means that are already in place; and then later take money from people in proportion to how much they have (i.e. tax the rich) to cover that expenditure, once this crisis is over. -

What are the First Principles of Philosophy?A first principle by its nature is supposed to be a necessary truth. So whatever a given philosophy takes to be first principles, it takes those to be necessary (and therefore eternal) truths.

I thought this thread was going to be about something much more interesting, and in case it actually is and I just don't see it in there, I'll say what I expected: what are the first principles assumed by philosophy as an activity, not by any particular philosophical systems? I.e. what are the principles held in common between people doing philosophy, violation of which means whatever you're doing is no longer philosophy?

I think those principles are:

- There are no unanswerable questions

- There are no unquestionable answers

Violating the first principle, we end up doing nothing, at least nothing even vaguely resembling philosophy. Violating the second principle, we end up doing religion (because we're appealing to faith), not philosophy (which by its nature appeals to reason).

I think that an entire philosophical system can be built out of just those two principles. -

CoronavirusWhat I heard was that massive companies aren’t getting reimbursed for the sick leave because they should be offering it anyway and they didn’t want to give a hand out to those megacorps.

-

CoronavirusWhat does any of that have to do with cronies?

Housing is most people’s biggest expense and there isn’t suddenly a dearth of that. People can keep living where they are, if only they are allowed to do so.And you know that how? — Janus

Debt servicing is the next big expense (student loans, car loans, mortgages, etc), and once more, money isn’t suddenly disappearing. People can just keep the money that they have, if they’re allowed to.

Food is always produced in huge surpluses, and we have vast stores of it set aside for emergencies, so people can eat that, if they’re allowed to.

Clothes aren’t suddenly disappearing. Cars aren’t suddenly disappearing. Phones aren’t suddenly disappearing.

Payment of money is usually the condition for which people are allowed access to things. Money has suddenly stopped flowing because work is the usual condition for getting access to money and people aren’t allowed to work anymore. So we could solve the whole financial crisis just by forcing money to flow from where it is concentrated to where it is lacking, from where it will flow back into concentrations again. Like CPR for the economy. -

CoronavirusThere are more than enough resources, the question is as always who is allowed to access them.

-

CoronavirusSo apparently the US has passed a bill requiring paid sick leave to people who have or are caring for people who have COVID19, except for large businesses... and small businesses. So, what businesses exactly count? And what about all of the tens of millions of people who don't have COVID19 yet, but have to stay home from work / got laid off / their hours reduced so that they don't catch or spread it?

-

How long can Rome survive without circuses?Once enough people in an area have already had and recovered from the disease, then they have immunity to it, and can't catch it from or pass it on to other people anymore, so the space between infect-able people grows larger automatically (and so the rate of new infections grows slower in proportion), and people don't have to artificially spread out and avoid each other to slow the spread anymore.

You're right that a neighboring area that has had no exposure can still catch it, and that area is then at the start of their own hump and has to take measures to flatten it out, but the places that already had it spreading through their community before can go back to normal themselves once they've gotten over that hump locally.

So whatever your community is, it's pretty much inevitably that eventually most people there will have had COVID19 at some point or another, but once enough people have had it and gotten over it, and the number of new cases is declining instead of increasing, there's no more risk of having too many cases at once and so people can go back to normal and whoever's left can get it and get it over with.

I saw a pretty good video about it yesterday that you might like:

-

How long can Rome survive without circuses?"Getting over the hump" seems like it would take a good deal more than a year or two? — ZhouBoTong

From what I understand, China is already over the hump locally, and it's only been like three months, and they didn't take the drastic measures we are.

I am curious to hear what your reply to my earlier post was going to be, too. -

Metaphilosophy: Historic PhasesThat's not true, though – substantive inquiry is certainly not just a conversation. Philosophy puts on some of the superficial trappings of inquiry, which involves discussion, but if you look closer, often no inquiry is happening. — Snakes Alive

The process of actually doing the inquiry involves a lot of stuff that is not just conversation, yes, but the process of setting up that process is very much like talking about talking. To get something like science underway, the people involved need to have broad agreement on some general things, like:

What do the questions we're asking even mean? What exactly are we asking, in this inquiry? An answer to this could be something like the verificationist theory of meaning. Analytic philosophy leans very heavily on this kind of question, and arguably even the Socratic dialogues are basically quests for adequate definitions of the terms used in other, more substantive inquiries.

What criteria do we judge answers to those questions by? What counts as evidence that a proposed answer to a question is true? An answer to this could be something like empiricism.

What method do we use to apply those criteria? An answer to this could be something like critical rationalism. This is the part most like the "litigation" you're emphasizing, having to do with burdens of proof and such. Is some account of the world to be presumed right by default until we find some reason to think otherwise, or are no accounts acceptable until one has been conclusively proven, or are all accounts equally possible until we find some reason to judge one over another...?

What should we take to be the relationship between the objects of our inquiry and we, the subjects doing the inquiring? Are we to think ourselves objective judges of something wholly independent of us? Or that the objects of our inquiry are dependent upon we subjects, created by us or by the very act of inquiry? Or that we subjects and the objects of our inquiry are interdependent parts of one system and what we're actually investigating is the relationship between ourselves and other things no different than us?

Who gets to do this inquiring? Is this to be a decentralized democratic process, or do some people have privileged or authoritative positions and their judgements carry more weight than those of others? Does it matter how many people make the same judgement? How, generally, should the social endeavor of inquiry be organized, for its findings to be reliably legitimate?

What are we asking for? Why are we inquiring into the things we're inquiring into? What is our objective or purpose? What use are answers?

These are the kinds of questions that philosophy purports (and I argue, genuinely endeavors) to answer. -

How long can Rome survive without circuses?From what I understand, it's not to stop the spread but to slow the spread. The big difference between COVDI19 and usual flu-like diseases is how quickly it spreads, which means that we can very suddenly end up with our medical system completely overwhelmed even by the small fraction of people who are seriously vulnerable to it, because they could all end up in critical need right away at the same time. If we slow down the spread of it, then we never cross that threshold of having too many people getting critically ill all at the same time, even if the same number of people end up having been sick overall by the end.

So we don't need to wait until there's a vaccine before things can go back to normal, just until we get over the hump of the curve. Once the number of new cases starts going down (even if just because there are fewer people who haven't gotten sick yet left), we don't have to worry about slowing its increase anymore, and can go back to normal knowing that the medical system won't be overwhelmed by those who depend on it. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsWhile my first inclination is to agree, checking myself I ask: how would I feel if Trump cancelled an election for the same reason? Suspicious. So damned if you do...?

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsI really wonder what effect this will have on both the election and the future of our political parties in general, if republicans of all people end up being the ones to roll out a UBI.

Of course, they’ll probably find some poison pill to stick in there, that will save everyone from the crisis now, medically and economically, and then as a consequence destroy social security and medicare next year or something. -

Metaphilosophy: Historic PhasesBut yeah, the larger problem is that philosophy asks about things besides conversation, and believes it can gain knowledge about them by conversing. This can happen sometimes, and of course conversation isn't totally useless, but the idea that you can get knowledge about the fundamental features of the world by talking about them as if you are in a courtroom is absurd, and, so I claim, culturally contingent. Like many culturally contingent things, from the outside it even looks absurd. — Snakes Alive

I know that this isn't universal across philosophers, either contemporary or historically, but the core subject that I view philosophy being about is not features of the world itself, but the process of inquiring into those features. My take on philosophy is entirely about "conversation" as you put it, because the process of inquiry is basically a conversation, both literally between people doing that inquiry, and more figuratively between the inquirers and the world they're inquiring into.

This is a very common theme in Analytic philosophy, which explicitly makes its focus all about language, and in doing so does actually dismiss a lot of previous philosophy, and contemporary philosophy that doesn't follow that route. I see a lot of it in Pragmatic philosophy too, where the content of an idea (about which we might talk) is grounded in the practical implications of that idea. I think it's the pragmatic grounding of talking about talking that really makes philosophy what it is. I said about as much earlier:

If you're doing ordinary work, that's not philosophy.

If you're administering the technology or businesses involved in doing that work, that's not philosophy.

If you're creating new technologies or businesses, that's not philosophy.

If you're investigating the "tools" and "jobs" out of which / toward which to create new technologies or businesses, that's not philosophy.

If you're asking how to go about doing that investigation, analyzing the ideas involved, and trying to persuade others that those are the ideas that are useful in conducting such an investigation, now you're doing philosophy.

If you're just analyzing the structure or presentation of those ideas, without regards to their practical applications anymore, then you're not doing philosophy anymore.

If you're just studying the language used to even discuss any of that, you're still not doing philosophy anymore. -

How long can Rome survive without circuses?Because we don’t know how long this total shutdown of society in response to the pandemic will last.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum