Comments

-

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementIt's not so black and white. Antecedent events may influence events, not necessarily exhaustively determine them. — Janus

You can have a mix of determinism and randomness, sure, not just 100% of one or 100% of the other. But still the only thing you've changed about the fully deterministic picture is to add some randomness to it, which doesn't really seem like it makes anyone more free in the sense that matters to us, a morally relevant sense. "I only did it because prior events determined that I would" and "I only did it because as random chance would have it that's what I ended up doing" both sound just as bad, and "I only did it because it was the one out of several possibilities allowable by prior events that I randomly ended up doing" is no better. -

What is a 'real' philosopher and what is the true essence of philosophy ?The problem is that we have no way of judging who on the ship is an able helmsman independent of the opinions of those on the ship, who all think themselves able helmsman. That’s not to say that there is no such thing as able helmsmanship or that it is not better that the ship be helmed by someone who is able rather than someone who merely thinks he is but isn’t. It’s just to say that everyone on the ship reckons that they are the most able helmsman and so on account of that the one who most deserves the helm.

IOW an actual philosopher-king would be great, but everyone equally reckons that they themselves would be that philosopher-king, and so anyone who stands up and says “away with all your mere opinions, I am the one with true knowledge!” is most likely just yet another fool who thinks himself wise, his supposed knowledge just more opinion. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementApplause for the inclusion of at least the conception of a metaphysical will. — Mww

:up: A general tactic I like using in philosophy is recognizing positions that claim to be competing answers to the same question to instead be answers to completely different questions. I did a similar thing in my thread on philosophy of mind ("by 'mind' do you mean a mental substance, the having of first-person experiences, or a kind of functionality? I have different views on all three of those things"), the same tripartite split here, in my thread about dissolving normative ethics I take something like utilitarianism and something like Kantianism as good-ish answers to two different ethical questions... come to think of it even my core philosophical principles are all about differentiating between different senses of broad concepts like "objectivism", "subjectivism", "skepticism", and "fideism", and approving of one sense while disapproving of the other.

I don't have any objections to any of what you said, and it reminds me of a thought that I had a long time ago regarding determinism and free will: if determinism is true, it works backward just as much as it works forward: things that I do right now logically necessitate that things have happened in the past such that I end up doing the things I do right now. So, if determinism is true, then by typing this sentence I have determined that the dinosaurs went extinct -- because me typing this sentences necessitates me being here, which necessitates humans evolving, which necessitates the dinosaurs having gone extinct. But of course, in the way we usually talk about willing and choosing, it's ridiculous to say that by typing that sentence I chose for the dinosaurs to go extinct; the dinosaurs going extinct is just a necessary condition of me choosing to type that sentence. And because determinism is time-symmetric, it works the other way around too: (if determinism is true) the dinosaurs going extinct necessitates that I choose to type that sentence, but that has nothing to do with it being my free choice to type that sentence, because the usual way that we talk about "free choice" has nothing to do with the logical relations between disparate periods of time.

Or, an even simpler version of the above, relating back to the problem of future contingents: suppose metaphysical libertarianism were true. Presumably most people would still say that there are facts about things that happen in the past, right? I'm about to freely choose a word to type: freebird. Now the fact of my choosing that is in the past. There is a fact now about what I did choose in the past. Does that entail that my choice could not have been free? Ordinarily we would say no. So why does it matter if there's a fact about what I will do in the future, any more than it matters there's a fact about what I did in the past? It has no bearing on whether the thing I do is chosen freely or not. -

Historical Evidence for the Existence of the Bicameral Mind in Ancient SumerI thought it was very cool when the HBO show "Westworld" incorporated the concept of a bicameral mind into their depiction of artificial intelligence achieving true self-awareness: that being when one realizes that the voice in their head telling them what to do is their own voice, not something outside of themselves.

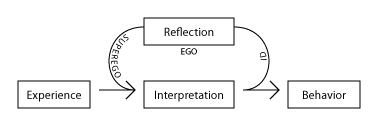

I just wrote something on a similar topic in my latest thread, though I relate it more to Freud's id, ego, and superego there, more of a "tricameral" mind; but I could see how that phenomenal appearance of three-part-ness could be implemented in a two-part brain:

...None of this is yet sufficient to call something free will in our ordinary sense of the word. For that, we need all of the above plus also another function, a reflexive function that turns that sentient intelligence back upon the being in question itself, and forms perceptions and desires about its own process of interpreting experiences, and then acts upon itself to critique and judge itself and then filter the conclusions it has come to, accepting or rejecting them as either soundly concluded or not. That reflexive function in general I call "sapience", and the aspect of it concerned with critiquing and judging and filtering desires I call "will" proper.

(I see the concepts of "id", "ego", and "superego" as put forward by Sigmund Freud arising out of this reflexive judgement as well, with the third-person view of oneself that one is casting judgement upon being the "id", the third-person view of oneself casting judgement down on one being the "superego", and the first-person view of oneself, being judged by the superego while in turn judging the id, being the "ego"; an illusory tripartite self, as though in a mental hall of mirrors). — Pfhorrest

-

Does Labor Really Create All Wealth?Is beer better if you can chat with a live bartender? I'd say, definitely -- live person, please. — Bitter Crank

Then that is a job that still calls for human labor -- the emotional labor of being a friendly person to talk to, even if the actual drink-making part of the job is automated away. If people prefer to have a drink somewhere that there's a live bartender to chat to, they will patronize the places where a live bartender pushes the make-me-a-beer button for you, instead of places where you push it yourself and then sit alone with your own thoughts wallowing in sadness and spoiled barley water.

Ricardo and Marx, primitives that they were, referenced actual live human labor, not automated machines. It is true, though, that machines impart some of their cost and value to the goods produced. — Bitter Crank

I think there's a couple of different things to be teased apart in this topic. One is the nature of wealth in the abstract, what makes something of value in general? The other is the question of where humans fit into that abstract picture.

I think I'll just quote myself from a recent thread of my own for my answer to that first question:

...purpose is the prescriptive analogue of the descriptive ontological concept of causation: cause is about why something does happen, while purpose is about why something should happen.

[...]

Similarly, the prescriptive analogue of the descriptive ontological concept of substance is wealth: wealth is stuff of value. And just as in my ontology I hold real objects of substance to be constituted by the things they cause to happen (ala "to be is to do"), so too I hold that the value of wealth is constituted by the purpose that it serves: a thing is of value for the good that can be done with it.

This concept of wealth can be further decomposed into concepts of capital and labor, which in turn can be further decomposed to familiar ontological categories: capital is of value for the matter and space that it provides, while labor is of value for the energy and time that it provides. And just as matter is ultimately reducible to energy, so too capital is ultimately reducible to labor: capital is the distilled product of labor, worth at least the minimal time and energy it takes to obtain or create, and no more than the maximal time and energy it can save elsewhere.

Similarly, just as physical work happens when matter and energy flow through space and time, what we might call "ethical work" happens – good gets done – when wealth flows in an economy, each kind of wealth diffusing from where it is in higher concentration to where it is in lower concentration. — Pfhorrest

That last part then begins to segue into the second question above: where do humans fit into that abstract picture of wealth and value? In a capitalist economy, where all the capital is owned by a small fraction of the populace, the only thing of value most people have to offer in trade with the capitalist class is their labor. If machines obviate the need for labor, then most people cease to have value to the capitalist class, which poses the threat of an enormous problem, if most people have nothing to offer the parasites who claim ownership of the whole world in exchange for the right to use some of that world.

One solution to that problem could be a socialist revolution, seizing the means of production by state force. Maybe a relatively peaceful revolution, if enough people can be convinced by their own eminent starvation and homelessness to actually use the levers of democracy sensibly to make the state act in the common interest; but also maybe a more violent one, if the threat of eminent starvation and homelessness pisses enough people off enough.

However, circling back around to the abstract topic of theory of value, if machines obviate the need for labor, then cost of new machines is free (it takes no labor to make another one), and the value of yet another machine to someone who already has one is also zero (it saves no more labor to have more automation than you need), so the price of those excess machines should tend to zero, as there's nothing lost by just giving them away, letting all the poor people who used to have nothing but labor have a free automaton, since it costs the rich nothing to just let them do that. And it might save them the costs associated with a revolution of starving homeless masses.

That of course depends on the capitalist class acting even in their own rational self-interest, which I'm not completely convinced is something that can be counted on, since many people of all classes seem happy to cut off their own noses just to spite someone else's face. -

Does Labor Really Create All Wealth?Just because machines do the labor doesn't mean that labor isn't the source of wealth.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleTranshumanism is a specific technological means, and so is beyond the scope of philosophy, but it sounds like the people behind that site generally have the right goal in mind and if they're working on particular means to attain it that sounds good to me.

The complete abolition of all pain and suffering doesn't have to be practically feasible for the ethical principles I advocate to hold up. These specific principles here, about hedonism and universalism, are just about establishing the scale against which to measure the comparative goodness of several states of affairs. The complete abolition of all pain and suffering is would be way over at the extreme good end of that scale, but even far from that end of the scale, we can compare two states of affairs and see that one has less suffering than the other, and so is better (or at least, less wrong) than the other.

That doesn't necessarily tell us specifically what we morally ought to do -- on top of this very simple criterion, we also need a more complete methodology by which to apply it, that I'm doing a thread (or maybe several threads) about soon. But it at least tells us the direction to head, even if not how to get there. -

Many Universes and the "Real" one.If each moment is a (separate) temporal cross-sectional slice of "the universe" (in effect, like multiple universes of arbitrary, discrete, intervals), what makes today more real than other days? — 180 Proof

:100: :up: -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementTo freely will you need to not be restricted by anything. — Huh

That would be what I called 'metaphysical will' above, and gave arguments for why that is not a useful sense of the word "will"; but also, in practice everything is at least a little bit 'unrestricted', and so in that (useless) sense everything has at least a little bit of 'free will'. -

What is a 'real' philosopher and what is the true essence of philosophy ?What is the essence of philosophy? A quick and general answer would be that philosophy is about the fundamental topics that lie at the core of all other fields of inquiry, broad topics like reality, morality, knowledge, justice, reason, beauty, the mind and the will, social institutions of education and governance, and perhaps above all meaning, both in the abstract linguistic sense, and in the practical sense of what is important in life and why.

But philosophy is far from the only field that inquires into any of those topics, and no definition of philosophy would be complete without demarcating it from those other fields, showing where the line lies between philosophy and something else. Philosophy is not the same thing as religion, nor just sophistry; its not science, because it's independent of a posteriori facts, but neither is it just about ethics; and it's not the same thing as math, despite being all a priori, nor is it just a genre of literature, a form of art.

Philosophy uses the tools of mathematics and the arts, logic and rhetoric, to do the job of creating the tools of the physical and ethical sciences, i.e. for studying what is real and what is moral. It is the bridge between the more abstract disciplines and the more practical ones: an inquiry stops being science and starts being philosophy when instead of using some methods that appeal to specific contingent experiences, it begins questioning and justifying the use of such methods in a more abstract way; and that activity in turn ceases to be philosophy and becomes art or math instead when that abstraction ceases to be concerned with figuring out how to practically answer questions about what is real or what is moral, but turns instead to the structure or presentation of the ideas themselves.

Who is a real philosopher? The question is largely whether philosophy is a personal activity, or an institutional one. Given that I think that the faculty needed to conduct philosophy is literally personhood itself (sapience, consciousness and will), it should come as no surprise that I think that philosophy is for each and every person to do, to the best of their ability to do so.

Nevertheless, institutions are made of people, and I do value the cooperation and collaboration that has arisen within philosophy in the contemporary era, so I don't mean at all to besmirch professional philosophy and the specialization that has come with it. I merely don't think that the specialized, professional philosophers warrant a monopoly on the discipline.

It is good that there be people whose job it is to know philosophy better than laypeople, and that some of those people specialize even more deeply in particular subfields of philosophy. But it is important that laypeople continue to philosophize as well, and that the discourse of philosophy as a whole be continuous between those laypeople and the professionals, without a sharp divide into mutually exclusive castes of professional philosophers and non-philosophers. And it is also important that some philosophers keep abreast of the progress in all of those specialties and continue to integrate their findings together into more generalized philosophical systems.

But who is really "a real philosopher"? I feel torn between two answers.

On the one hand, if asked if someone else was "a real philosopher", I would just look at whether they do the activity that is philosophy, professionally or not; if they did any kind of study of those broad fundamental problems using those kinds of methods described above, I'd say yeah, they're a philosopher, especially if they wrote those thoughts down somewhere, or discussed them with others regularly.

But if asked if I was a "real philosopher"? I feel like I'd be compelled to answer "eh, not really", because I don't actually do this for a living. -

A saying of David HilbertThis reminds me of my thoughts on beauty qua elegance, which is to say, the intersection of a phenomenon being interestingly complex, but also comprehensibly simple. Complexity draws one's attention into the phenomenon, seeking to understand it; and if that complexity is found to emerge from an underlying simplicity, beauty can be experienced in the successful comprehension of that complexity by way of the underlying simplicity.

That is to say, symmetries and other patterns, that allow us to reduce a complex phenomenon to many instances and variations of simpler phenomena, are inherently beautiful in an abstract way. This is the kind of beauty to be found in abstract, non-representational art, and also in places besides art such as in mathematical structures.

The tension here between interesting complexity and comprehensible simplicity is, I think, what underlies the distinction many artists, audiences, and philosophers have made between what they call "high art" and "low art".

- Those who prefer so-called "high art" are those with enough experience with the kinds of patterns used in their preferred media that they are able to comprehend more complex phenomena than those less experienced, but simultaneously find simpler phenomena correspondingly uninteresting.

- Those who prefer so-called "low art" (so called by the "high art" aficionados, not by themselves) instead find more complex phenomena incomprehensible, but are simultaneously more capable of taking interest in simpler phenomena.

Unlike the attitudes evinced in the traditional naming of these categories, I do not think that "high art", a taste for complex phenomena, is in any way inherently better than "low art", a taste for simple phenomena. In each case, the aficionados of one are capable of appreciating something that the other group cannot, while incapable of appreciating something that the other group can.

In my opinion, if any manner of taste was truly to be called universally superior, it would be a broader taste, capable of comprehending complex phenomena and so appreciating "high art", while still remaining capable of finding simple phenomena interesting and so appreciating "low art". In that way, audiences with such taste would be best capable of deriving the most enjoyment from the widest assortment of phenomena, both natural and artistic. -

Do Atheists hope there is no God?That question doesn't make any sense. How do my higher priorities -- things like keeping myself alive -- "match how things really are"? What does that even mean?

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleY'know, it has often seemed to me that far too many people show too much disdain for truth, but it's rare that any of them straight up admit it like this.

-

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleWhy on earth would anyone want to do that?? — baker

...so that their models would remain accurate in light of new information?

Between this and your say similar question in that atheists thread, you come across as baffled by why anyone would have any concern for truth. -

The Poverty Of ExpertiseNever discount the value of your knowledge when you go to the see your doctor. Tell him/her everything you can remember about your issue. You have no idea how much this helps! — synthesis

I always come to doctors (and most any kind of expert) with all the information I can and what analysis I’ve done of it myself and where I got stuck trying to figure it all out myself (which is why I’m now seeking expert help)... and more often than not come away with an off-the-shelf non-solution that doesn’t account for most of the details of my particular case. -

The Poverty Of ExpertiseVery Socrates of you..ha — schopenhauer1

Good observation! I honestly never noticed that parallel. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementNo worries, I'm just happy that anyone is engaging with my ideas at all! I just thought maybe I wasn't clear what those ideas were. I agree with you that we need institutes of justice, and more generally methods of justice for those institutes to exercise, and my very next thread is going to be about those methods, which is to say, how to conduct the will. :-)

-

Do Atheists hope there is no God?You do realize how immensely impractical this is, do you? I'm sure you do.

I also doubt you practice it consistently. You aren't all that concerned about the truth about the half-life of radioactive isotopes that exist only on Triton or the vaginal system of fleas, are you? — baker

“Only things that are true” doesn’t mean “all the things that are true”... but yeah, knowing all the things would be cool too, though of course I have higher priorities in daily life. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementI'm not arguing against institutes of justice, if that's what you're talking about. I'm not saying that we should just "let our free will judge what is morally good", as in "do as thou wilt shall be the whole of the law".

What I'm suggesting in this thread is that what it means to "freely will" something is to judge that something is the correct thing to do, and then have that judgement actually guide your actions; in contrast to doing something you didn't mean to do, or something that you didn't realize was a bad thing, or something you just didn't give any thought to, or anything like that, which are all paradigmatic cases of un-free will.

People exercising their will / moral judgement are still likely to make errors in that judgement, so it's still important that other people correct them, but that's a different topic to the one that I'm talking about here, which is simply "what does it even mean to will something?" I think it means to judge something as the correct course of action. And for that will to be free is for that judgement to actually direct your action. -

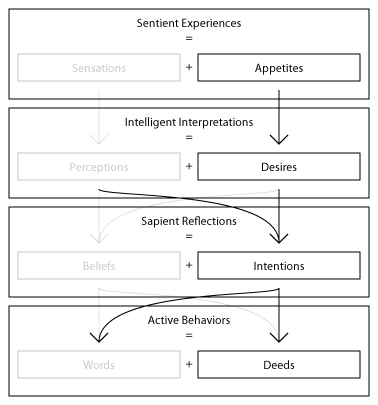

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementOn Intentions

None of this is yet sufficient to call something free will in our ordinary sense of the word. For that, we need all of the above plus also another function, a reflexive function that turns that sentient intelligence back upon the being in question itself, and forms perceptions and desires about its own process of interpreting experiences, and then acts upon itself to critique and judge itself and then filter the conclusions it has come to, accepting or rejecting them as either soundly concluded or not. That reflexive function in general I call "sapience", and the aspect of it concerned with critiquing and judging and filtering desires I call "will" proper.

(I see the concepts of "id", "ego", and "superego" as put forward by Sigmund Freud arising out of this reflexive judgement as well, with the third-person view of oneself that one is casting judgement upon being the "id", the third-person view of oneself casting judgement down on one being the "superego", and the first-person view of oneself, being judged by the superego while in turn judging the id, being the "ego"; an illusory tripartite self, as though in a mental hall of mirrors).

The output of that function – an experience taken as imperative, interpreted into a desire, and accepted by sapient reflection – is what I call an "intention".

As you may recall from my earlier thread on meta-ethics and the philosophy of language, I take such intentions to be equivalent to what are sometimes called "moral beliefs", or more accurately, the normative equivalent of beliefs, prescriptive thoughts or judgements (as distinguished both from descriptive thoughts, or beliefs, and from prescriptive feelings, or desires). The forming of intentions is what I take to constitute willing, so the will (and its intentions, and their predecessors like desires and appetites) is on this account the "subject of morality" in the same way that the mind is the "subject of reality": it is the aspect of subjective experience that is concerned with morality, with what ought to be.

The will, in this more important sense of psychological will rather than metaphysical will, is not at all about causation or lack thereof, but about purpose, a prescriptive issue, not a descriptive one. And the efficacy of willing upon actual behavior is what I take to constitute freedom of the will: you have free will if the process of deliberating about what is the best course of action is effective in making you do what you decided would be the best course of action; which is about causation, yes, but only in that it depends upon it, not in that it is threatened by it.

The proper conducting of this process of willing or intention-formation is the subject of the next thread I'll do once this one dies down, which, as promised earlier, will also tackle the last of the three philosophically interesting senses of "free will" laid out near the start of this thread, the sense equivalent to liberty, as well as its inverse, duty. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementOn Appetites and Desires

As with consciousness, the first of these important functions, which I call "sentience", is to differentiate experiences toward the construction of two separate models, one of them a model of the world as it is, and the other a model of the world as it ought to be. These differentiate aspects of an experience, which as outlined in my thread about ontology is an interaction between oneself and the world, into those that inform about about the world, including what kind of things are most suited to it, which form the sensitive aspect of the experience; and those that inform about oneself, and what kind of world would be most suited to oneself, which form is the appetitive aspect of the experience.

From these two models we then derive the output behavior from a comparison of the two, so as to attempt to make the world that is into the world that ought to be. This is in distinction from the simpler function of most primitive objects, where experiences directly provoke behaviors in a much simpler stimulus-response mechanism, and no experience is merely indicative of the nature of the world, but all are directly imperative on the next behavior of the object.

Those experiences that are channeled into the model of the world as it is I call "sensations", and I have already discussed them, their interpretations into perceptions, and the reflection upon perceptions to arrive at beliefs, in my earlier thread on the mind.

Meanwhile, those experiences that are channelled into the model of the world as it ought to be I call "appetites". Appetites are the raw, uninterpreted experiences, like the feeling of pain or thirst or hunger. When those appetites are then interpreted, patterns in them detected, identified as abstractions, that can then be related to each other symbolically, analytically, that is part of the function that I call "intelligence" (the other part of intelligence handling the equivalent process with sensation), and those interpreted, abstracted appetites output by intelligence are what I call "desires", or "emotions". -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementOn Psychological Will

The pragmatically useful sense of "free will" is, I hold, a functional one, just like the pragmatically useful sense of "consciousness". Just producing behavior that is not determined by experience is not really anything of note; it is the function that produces that behavior that may or may not be worth considering "free willed" in the ordinary sense that we use that term.

And not only is randomness or non-determinism unnecessary for such a function to constitute free will in that ordinary sense, but too much randomness, or too little determinism, would actually undermine that function, because I hold freedom of will to be essentially the ability to evaluate reasons to do one thing over another, to weigh possible intentions against each other and decide which of them is the right one to intend, and then for that evaluation to be actually effective on your behavior (as opposed to either not doing such an evaluation to begin with, or to finding yourself behaving in ways you had already decided you shouldn't, as from a compulsion or phobia). Randomness would only add errors to the evaluative process, or impede it's effectiveness upon behavior, and so only serve to undermine free will, not to enhance it.

I call this combination of pan-libertarianism about metaphysical will and functionalism about psychological will "functionalist pan-libertarianism". And like with consciousness, defining exactly what the function of a free will is in full detail is more the work of psychology (mapping the functions of naturally evolved minds) and computer science (developing functions for artificially created minds) than it is the proper domain of philosophy, but for the rest of these posts I will outline a brief sketch of the kinds of functions that I think are important to qualify something as a free will, in the ordinary sense by which we would say that humans definitely sometimes have free will, and dogs occasionally might, but a tree probably never does, and a rock definitely does not. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementPan-Libertarianism

That latter position is what I have dubbed pan-libertarianism: the view that everything at least has something prototypical of metaphysical agency as we mean it regarding human will. That is the position that I hold: the kind of free will that incompatibilists are concerned about, that I've called "metaphysical will", is something that everything, even and especially the most fundamental particles in the universe, has. But in saying that everything has metaphysical will, I'm not really saying very much of substance.

It is merely the flip side of my panpsychist philosophy of mind, in light of the relationship between experience and behavior outlined in my earlier thread about ontology: every experience is in truth an interaction, seen equally well from a different perspective as a behavior instead of an experience.

Indeed, just as I compared that kind of panpsychist phenomenal experience to quantum-mechanical "observation" (distinguished from a more useful and robust access-conscious sense of "observation"), so too in quantum mechanics are those "observations" held to in fact be simply interactions, and it is those very interactions that introduce randomness, or at least the subjective appearance of randomness, to a quantum-mechanical model of the world (which otherwise models everything as deterministically evolving wave functions until the moment of "observation", or interaction with another system, at which point, at least from the perspective of the "observer", the wave function appears to randomly collapse into one of many possible classical states).

I hold that everything, even simple particles like electrons, has "free will", but only to the same extent that they have "consciousness": in an obscure technical sense they do, but only a pragmatically useless sense of the word that is only the topic of long-intractable philosophical quandaries.

Everything has control (and thus freedom) of some sort, in that its very existence changes the flow of events – otherwise they would not appear to exist at all, and so not be real at all on my empirical realist account of ontology – but only some things have self-control, and that is what the rest of these posts will discuss. Being able to predict what someone or something will do is not the same as them being forced to do it in any practical sense, and likewise, merely being unpredictable is not a pragmatically useful kind of freedom. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementAgainst Emergent Libertarianism

I am also against what I dubbed above emergent libertarianism, as a part of my general position against (strong) emergentism, as already elaborated in my previous thread on the mind. I am against such emergentism on the grounds that it must draw some arbitrary line somewhere, the line between things that are held to be entirely without anything at all like metaphysical will and things that suddenly have it in full, and thus violates my previously established position against dogmatism.

Strong emergentism holds some wholes to be greater than the sums of their parts, and thus that when certain things are arranged in certain ways, new properties apply to the whole that are not mere aggregates or composites of the properties of the parts. Specifically, as regards philosophy of will, it holds that when simpler objects, that do not themselves have metaphysical free will on this account, are arranged into the right relations with each other, wholly new volitional properties apply to the composite object they create: a being with metaphysical free will is created from parts none of which had metaphysical free will.

I do agree with what I think is the intended thrust of the emergentist position, that will as we ordinarily speak of it is something that just comes about when physical things are arranged in the right way. But I think that will as we ordinarily speak of it is psychological will, to be addressed later in these posts, and that psychological will is a purely functional, deterministic property that is built up out of the ordinary deterministic behavior of the things that compose a psychologically willful being, and nothing wholly new emerges out of nothing like magic when things are just arranged in the right way.

So when it comes to metaphysical will, either it is wholly absent from the most fundamental building blocks of physical things and so is still absent from anything built out of them, including humans, or else it is present at least in humans, and so something of it must be present in the stuff out of which humans are built, and the stuff out of which that stuff is built, and so on so that at least something prototypical of metaphysical will as humans exhibit it is already present in everything, to serve as the building blocks of more advanced kinds of metaphysical will like humans exhibit. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementAgainst Hard Incompatibilism

I am against hard incompatibilism, strictly speaking, though I am very sympathetic to the motivations for it. The incompatibilist quest for a useful notion of free will that depends on non-determinism, but is not simply randomness, does seem impossibly quixotic, because non-determinism simply is randomness. But I do not consider metaphysical will to be the useful notion of free will in the first place; that, I hold, is psychological will, which will be explored later in this post. But in answering the question of whether anything could possibly have metaphysical will or not, as useless a question as that may be to ask, I disagree with the hard incompatibilist that randomness undermines the possibility of it.

Instead, I hold, randomness is the entire essence of it: to have metaphysical will is just for the being in question to have a behavior, an output of its function, that is not entirely determined by its experience, the input of its function, and that simply is a definition of randomness. Too much randomness, or insufficient determinism, does indeed undermine the possibility of psychological will, which depends on an adequate degree of determinism to reliably maintain the functionality that constitutes it, but that is a separate question from whether anything has metaphysical will.

Against the hard incompatibilist, I hold that it is possible for things to have metaphysical will, because that would simply mean that determinism was false, which it very well could be (and according to contemporary theories of physics, it effectively is).

And if we instead slightly loosen the criterion for metaphysical free will from strict indeterminism to mere unpredictability, I hold that that is a necessary feature of any possible universe, regardless of whether determinism is strictly true or not, because predictability is self-defeating. An indeterministic universe would of course be unpredictable, but even a perfectly deterministic universe could not possibly be perfectly predictable, because the ability to perfectly predict the future is equivalent to information from the future coming to the past, and such backward transfer of information necessarily changes the future that proceeds from the moment of prediction.

In other words, predicting the future necessarily changes it, and thus renders the prediction, to some (if perhaps negligible) extent, inaccurate. These kinds of unstable feedback loops in dynamical systems, even perfectly deterministic systems, are called "chaotic", and all chaotic features render such systems inherently unpredictable, if for no other reason than the process of computing an accurate prediction in the face of such unstable complexity would necessarily take longer than the system being predicted would take to reach the future we're trying to predict.

Daniel Dennett calls this kind of unpredictability "elbow room", and holds it to provide for a kind of "compatibilist" free will that does not clash with determinism. But I hold that this sense of "free will" is still essentially the same sense as the one that incompatibilists concern themselves with – unpredictability is still not freedom of will in the ordinary, morally relevant sense, the sense that I call "psychological will" – and so is not really "compatibilist" in the same way that other forms of compatibilism are. -

The "subjects of morality": free will as effective moral judgementOn Metaphysical Will

Metaphysical will is largely defined by its independence from the functional process of deliberation, in much the same way that phenomenal consciousness is defined by its independence from the functionality that defined access consciousness. If we stipulate the existence of some being, like a computer artificial intelligence, that performs a deliberative process of weighing evidence and priorities and determining a course of action that is exactly like the kind of deliberative process that a human being would do, there would still be an open question as to whether such a being has metaphysical will. That is because metaphysical will is not about that function, but about the metaphysics of the causation that underlies that function.

Incompatibilists generally argue that if such a deliberative function programmed into the being behaved deterministically, always giving the same output for the same inputs, in other words always making the same decision about what the best course of action is given the same knowledge of the same circumstances and the same priorities and so on, then it would not have freedom of its metaphysical will, if it could even be said to have such a will at all.

But a counterargument, often called "The Mind Argument" for its prominence in a philosophy of mind journal called Mind, argues that if the execution of that function did not happen deterministically but instead sometimes randomly produced outputs that did not follow from the inputs, that would hardly seem to add any kind of substantial freedom to the process, because blindly following a dice roll to make a decision seems, if anything, even less free than deterministically weighing evidence and so on to make that decision. Metaphysical will is the kind of thing that is at question in these kinds of debates about determinism and randomness, regardless of what exactly the deliberative function that (deterministically, randomly, or somehow otherwise) chooses some course of action may be.

Without an answer the question of whether the universe is entirely deterministic or not, there are generally three possibilities when it comes to what kinds of beings might possibly have metaphysical will: either nothing could possibly have it, not even human beings, because the concept is simply confused nonsense; some beings, like humans, could have it, if the universe is not entirely deterministic, but not all beings would thereby have it; or if anything at all could have it, then all beings, not just humans but everything down to trees and rocks and electrons, would have it.

The first of these position, the view that nothing can possibly have metaphysical free will because the concept is confused nonsense, is called hard incompatibilism; while the latter two positions are variations of the view called metaphysical libertarianism, which so far as I know do not have well-established names for themselves, but I will dub them emergent libertarianism and pan-libertarianism for my purposes here. -

What would you leave behind?So what would you leave behind if anything and why? — FlaccidDoor

"It may be hopeless, but try anyway."

Also, can I leave a book? Because I wrote like 80,000 words elaborating on that principle already. -

Science and the Münchhausen TrilemmaGood! Then we are in agreement. (How often does that happen in a philosophy forum?) — Amalac

Rarely in my experience. :up: :clap: :100: -

Science and the Münchhausen TrilemmaBut see, though we would call someone who believed that the sun won't rise tomorrow or that he'd be able to fly in a couple of days by moving his arms really fast an insane person, there is nothing logically impossible about those things happening. They are conceivable.

Of course there is no reason to believe that the sun won't rise tomorrow, but it seems that there is also no reason to believe that it will rise (besides pragmatic reasons).

So if we look at it from the angle of pure logic, the choice between believing that the sun will rise tomorrow or that it won't resembles the choice between believing that a coin will land on heads after flipping it, or that it won't.

But the choice is illusory: since we are accustomed from early infancy to believe that it will rise, no one can get rid of this habit easily, and to attempt to do so would contradict basic human psychology. — Amalac

Sure, and that all sounds perfectly consistent with critical rationalism. We can’t know for sure what patterns phenomena in the universe follow. But we’re rationally allowed to think that they follow the patterns they seem to follow — or to not think that, if for some reason we’re inclined not to. And we can be sure when the universe does NOT follow a particular pattern.

It’s the swans thing. We can’t ever be sure that all swans are white, but we’re not irrational to think they are if it seems so, and we can be sure that NOT all swans are white, given a black swan.

I don’t mean to derail your whole thread about the trilemma with this debate about critical rationalism, especially when I already have a separate thread about critical rationalism that also touches on its relationship to this trilemma:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/9571/critical-liberal-epistemology -

Science and the Münchhausen TrilemmaBut it seems that theoretically it is just as irrational as the opposite assumption, as I pointed out in my previous response to you. — Amalac

I think more in terms of the opposite assumption being “pragmatically falsified”, in that it’s a self-defeating assumption, leaving only something within the broad scope of its negation as possible—but without affirming any one of the innumerable variants within that scope as the definite truth. -

What is a 'real' philosopher and what is the true essence of philosophy ?I imagined you having some kind of community of philosophers, so I am obviously wrong. If only.. — Jack Cummins

There were philosophy discussion clubs for philosophy students at colleges, but nothing for mature adults that I’m aware of. Looking for something like that is what brought me here. -

What is a 'real' philosopher and what is the true essence of philosophy ?You are in America and it may be that there is some kind of culture in which philosophy is recognised outside of academic circles. — Jack Cummins

Not really, and probably even less than England. America is absurdly anti-intellectual in general. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principleHow does 'what feels good is good' work for e.g. sadists, masochists, severe autistics or antisocial sociopaths (e.g. neo-nazi thugs, serial rapists, billionaire ceo union-busters)? :chin: — 180 Proof

We’re discussing this in another thread right now:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/10539/at-long-last-my-actual-arguments-for-hedonic-moralism

This is the point of distinguishing between appetites and desires: an appetite is not aimed for any specific state of affairs like a desire is, it’s just a feeling that calls for something or another—and there’s always multiple options—to sate it.

And it’s also related to the problem of confirmationism and its analogue consequentialism that I’ll go into in the later thread on justice. “If you suffer, I will enjoy it” plus “I should enjoy myself” doesn’t logically entail “you should suffer”; that would be affirming the consequent.

You should enjoy yourself rather than suffer. Also, I should not suffer but rather enjoy myself. Those are necessary conditions of something being good. You enjoying yourself is not, however, a sufficient condition of something being good; if something causes you enjoyment but me suffering, or vice versa, it’s bad, and something else that brings us both enjoyment rather than suffering must be found if we are to bring about good.

If that something else is not something that either of us wanted at the outset, that’s fine; we were both wrong about what was good. It’s up to us to figure out what we should both want, that will satisfy both of our appetites. — Pfhorrest

I think the above also answers this:

negative hedonic utilitarianism', is more eudaimonic and less relativist than a "ethical (positive) hedonism" — 180 Proof

I am not at all advocating consequentialism and thus no variety of utilitarianism per se, though I broadly agree with utilitarianism on what a good state of affairs is. But I don’t think those ends justify any and all means. Hedonism doesn’t mean anything more specific than that pleasure and pain etc are all that’s morally relevant, that if something is good or bad it is for the reason of some (dis)satisfaction it brings someone. Your negative utilitarianism is still within the scope of that, and very close to the methods that I advocate on pursuit of the ends we’re discussing here. -

Science and the Münchhausen TrilemmaThe critical rationalist can’t ever hope to find certain knowledge about what is true, sure

— Pfhorrest

And so, he can't find certain knowledge about:

but we can accumulate more and more knowledge about what is false.

— Pfhorrest — Amalac

No? We can be certain that a particular combinations of beliefs is false, if they lead to contradiction. We can’t ever be certain that any particular combination beliefs is true, but we can’t help but act on an assumption one way or the other, and only one of those assumptions can possibly hope to lead us to any greater knowledge, so that is the rational one to make. -

Do Atheists hope there is no God?That's bold! Is it true? — bert1

So far as I can tell, which is the most certain anyone can ever be about anything. -

The Poverty Of ExpertiseI’m always trying to find experts to whom I can defer because I really want to not be the ultimate authority on things since I know how little I know, but the longer I try to find such experts the more I realize that nobody really knows much of anything and you can’t really defer to anyone.

-

Science and the Münchhausen TrilemmaThe critical rationalist can’t ever hope to find certain knowledge about what is true, sure; but we can accumulate more and more knowledge about what is false. We can never finish accumulating all the knowledge of what is false, to pin down exactly one thing that is true, but that doesn’t change that at one point in time we think more things are maybe-true than we do at a later point in time, and so have narrowed down on the possibilities.

And the reason to take experience as the arbiter of truth is because the alternative leaves us with no ability to question the truth of any claims, and so removes even the above kind of progress. If things might be true or false in ways that make no difference to what seems true of false in our lived experience, then there are either questions about such things that cannot be answered, or else the answers to such cannot be questioned.

Either of those might in principle be the case, but if they were we could not know, just assume one way or the other; and to assume either unanswerable questions or unquestionable answers is simply to give up trying, so we must always assume to the contrary.

I don’t see the connection of any of this to the trilemma though. -

A poll on hedonism as an ethical principletaking it for granted and taking for granted that said distnction can always be reliably established for every person at any given time. — baker

For the sake of that illustration I take it for granted, but that is just an illustration. Whenever it is discovered that a person with such and such characteristics experiences such and such phenomena differently that other people, our models have to be updated to reflect that. -

Do Atheists hope there is no God?Why do you want to "decide whether God exists or not"? — baker

Same reason I want to decide the truth of any other claim: I want to believe only things that are true, and avoid believing things that are untrue.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum