Comments

-

Does anyone know about DID in psychology?That makes me think of the psychological hypothesis of bicameralism, according to which schizophrenia is a throwback to an earlier form of human mental function wherein the left hemisphere of the brain (responsible for normal language use) perceived the equivalent part of the right hemisphere as an external voice, "a god", in place of the self-aware internal dialogue that most modern humans have, wherein we do "talk to ourselves" in our minds but we're aware that it's ourselves and not some other being outside of ourselves speaking to us.

-

Does anyone know about DID in psychology?This makes me think of a hypothesis I've been mulling over lately: are all mental disorders just distortions or exaggerations of aspects of normal mental functioning? (I don't know if this is an active theory in real psychological research or anything, it's just a thought that passed through my mind recently when thinking about how people say they "are depressed" when they're sad or "have OCD" when they're fixated on niggling details, etc: are not the proper mental disorders just dysfunctionally severe versions of those same passing modes of normal function?)

If so, is DID perhaps an exaggeration of the normal tendency for people to behave "like different people" in different contexts, and have a feeling of conflict when multiple contexts overlap, calling for them to behave according to two contrary patterns at once? (E.g. be the "good kid" around parents, be the "cool rebel" around friends, so if visiting friends with parents, "what do?")

Also I wonder about the influence of how much of our self-identity is a story we tell ourselves about ourselves, so perhaps DID is "all a fake", but no more than anyone's usual self-identity is "a fake". The person with DID, perhaps, tells themselves that they are several separate personas sharing a body but not memories etc, and so to the extent that one's identity is all about the story one tells oneself, that fractured identity is true of them, because that is the story they tell themselves.

Combining those two things with the traumatic origins, I can see it making sense that someone who has suffered immensely and cannot function as needed because of that trauma creating a self-narrative featuring one character who had that trauma and is dysfunctional because of it (a part of themselves that's allowed to feel awful about the things that have happened to them), and also other characters who were not the subjects of that trauma but instead bystanders who witnessed it but are still capable of standing up to their abusers or fighting their way out of the situation or whatever.

Around a decade ago I had a kind of mental metaphor of myself along those lines. I felt like the person that I had been all my life prior to then had been "beaten to death" by life, but that that "zombie corpse" of my old self was propped up inside a "robot suit" that was stoic and hyper-functional, but unable to actually enjoy the life that it continued living on behalf of "old me". I was always aware that that was just a metaphor for how I felt, but I can easily see some thought process along similar lines leading to a self-narrative featuring multiple "selves", a story that one could in time convince oneself of. -

Can we see the world as it is?There's an old parable wherein three blind men each feel different parts of an elephant (the trunk, a leg, the tail), and each concludes that he is feeling something different (a snake, a tree, a rope). All three of them are wrong about what they perceive, but the truth of the matter, that they are feeling parts of an elephant, is consistent with what all three of them sense, even though the perceptions they draw from those sensations are mutually contradictory.

Though our perceptions -- our filling in of the gaps and extending of patterns and attempts to correct for distortions of our senses, in other words our interpretations of our senses -- can be wrong, our senses themselves cannot, and there is nothing more to the actual truth than the sum of what all kinds of senses (of any beings, not just us) could potentially sense. -

Evictions, homelessness, in America: the ethics of relief.What passes for capitalism today is a far cry from the invisible hand of Adam Smith. — fishfry

It's worth noting, to emphasize this point, that Adam Smith never advocated for anything called "capitalism". -

Modern PhilosophyGraeber is great, but yeah not really philosophy exactly. Very informative for political philosophy, though.

-

Can we see the world as it is?All that anybody ever sees is the world as it is, because there is nothing to the world but what it looks like. But nobody can ever see the entirety of the world, only small low-resolution band-limited parts of it at a time, that we piece together in our minds into as close an approximation of the whole thing as we can manage.

-

Evictions, homelessness, in America: the ethics of relief.I can only speak for California, but I know that Ronald Reagan (when our governor, pre-presidency) closed down all the state mental institutions there used to be in this state, and pretty much everyone who would have otherwise been living there just became homeless instead.

On the topic of homelessness and mental health, let's not forget that there are a lot of vicious circles involved here. Material conditions can cause a deterioration of mental health and vice versa. Leaving the mentally ill to fend for themselves on the streets only makes them more mentally ill. (Like putting criminals in with other criminals in prisons tends to just make them more criminal). Part of any serious mental health program has to be providing the patients with the material stability that they need to work on their mental health problems. -

My Moral Label?It doesn’t matter to you whether or not someone else’s observations match your own?

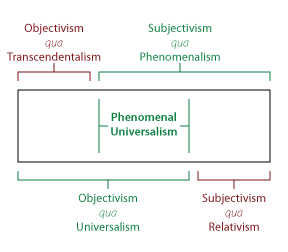

Edit to elaborate: When it comes to figuring out what is real, people generally find it intuitively "crazy" if someone denies either that their empirical experiences tell them anything about what's true or false, or that if something is true at all then it's true for everyone (and so whatever is true must satisfy everyone's empirical experiences). It's a little more common but still widely considered bad form to either insist that something just is definitely true regardless of its impact on empirical experience, or to insist that someone justify something beyond all shadow of a doubt or else be compelled to accept that it's false.

The analogous errors regarding morality are to deny either that hedonic experiences tell us anything about what's good or bad, or that if something is good at all then it's good for everyone (and so whatever is good must satisfy everyone's hedonic experiences); or to either insist that something just is good regardless of its impact on hedonic experience, or to insist that someone justify something beyond all shadow of a doubt or else be compelled to accept that it's bad.

Applied in practice, those moral principles mean, in reverse order: giving everything the benefit of the doubt that it might be good, by default; but defeasibly, accepting the possibility that it could be shown bad; treating anything (a particular event, not a whole class of events) that can be shown bad for anyone to be just bad period, even if other people don't think so; and appealing to hedonic experiences, suffering and enjoyment, pleasure and pain, as the measure of whether it's good or bad for someone. -

My Moral Label?Short version is suffering (phenomenologically, like as in pain) is bad, and nobody's suffering is any more or less important than anyone else's, and those things would cause someone to suffer. Suffering is bad and everyone's is equally important for the same reasons that observations can falsify beliefs and all observations matter. Which reason is pretty much because if we assumed otherwise (and we cannot help but tacitly assume one way or the other), we would be unable to rationally resolve disagreements or otherwise answer questions, either about what is true or what is good, and so would not have that map of where to go from where we are (so to speak), and so would be acting without that guidance and so would most likely fail (unless we just got super lucky) at whatever we're ultimately trying to do. Those assumptions could of course be false, but we could never be sure of that, and it would be imprudent to merely assume that rather than the contrary.

-

Who are the 1%?In most cases the best explanation is that some people have simply outproduced others. — geospiza

Yeah I'm sure Elon Musk just works a few million percent harder and smarter than the average American.

It is a fact that there are wide disparities in outcomes of wealth/income. It doesn't follow from this that some groups have been victimized by others. — geospiza

Sure, that conclusion doesn't follow necessarily from that fact, but lots of other more specific facts taken all together strongly suggest that something or another is amiss. There's room to debate what exactly, but dismissing all of that in favor of "probably some people just work harder/smarter/whatever than others" reeks of grinding an ideological agenda. -

My Moral Label?Appreciate your input in all of this. I just wanted to also say that I personally seem to lack much empathy. So, my principles are somewhat of a tangible line I don’t want to allow myself to cross, because it’s likely that my emotional response wouldn’t be strong enough by itself to prevent me from doing bad things. So for me personally, I probably need to develop some principles that guide me towards positive actions as well. Otherwise, I come across as being self-absorbed and inconsiderate, which I suppose I probably am. But that’s probably just a “me” thing. — Pinprick

That also sounds a lot like me.

Honestly I think emotional empathy is a pretty weak justification for any notion of morality. I want to say to some people who think that it grounds all of everyone's morality "so the only reason that you don't [insert awful thing] is because you just don't happen to feel like it, but if you did feel like it you'd just do it!?" And these same people seem to need some kind of self-interested excuse to do something nice for someone else.

Whereas on the other hand I feel like doing pretty awful things pretty frequently, but don't (usually, when I'm not in some kind of crisis state losing all self-control), because those aren't the kinds of things I think should be done, so why the hell would I do them if I could help it? And likewise, the question of "why do nice things for people" just perplexes me -- that's just the thing to do, and if it's not some kind of awful burden to do so, why wouldn't you just do that by default?

And not because my heart bleeds for all the poor souls out there. I shrugged the morning of 9/11 because that's something far away that I doesn't affect me personally (at least not immediately) and I can't do anything about. I don't really give a fuck about other people, emotionally, but when I'm deciding what to do myself, in my life, why wouldn't I do the thing (like help someone) that I think people generally should do (since I'm a person too), so long as I can manage it? -

Physicalism is False Or Circularall things physical are information-theoretic in origin and this is a participatory universe — Wayfarer

Which is pretty much what I was saying.

NB that that doesn’t imply that there are any non-physical things. -

Physicalism is False Or CircularIt is that Wheeler’s ‘participatory universe’ challenges materialism, because it places ‘the observer’ in the picture (‘the observer’ being the participant in question.) So this introduces ‘mind’ as fundamental, but not as an objective factor. It is fundamental because of its participation. — Wayfarer

Right, that's what made me think of the thought that I then posted. Like Wheeler's participation of the observer, on my view it is precisely our participation as part of the abstract object that is our concrete universe that makes it concrete, to us. There are other abstract objects very similar to our universe that contain within them structures much like the structures that we are, that participate as part of those objects/universes, and so experience them as concrete, whereas to us they are abstract -- and to them, our universe is an abstract object. It's being an interacting, participating part of this universe that makes it concrete from our perspective, and other structures that we are not part of abstract from our perspective.

But you can’t get behind that, or outside of that, so as to see what it is; it is not a ‘that’, an object of analysis, because it is always ‘what is analysing’.

Whereas, in your post, I feel as though you are trying to treat everything - mind included - as object. — Wayfarer

On my account, 'object' and 'subject' are roles in or perspectives on an interaction, and everything is both. It's true that we can't get out of our own perspective, except perhaps inasmuch as we can become something else so as to have the perspective of that kind of thing instead, but then we're still in our own perspective, it's just a different kind of perspective.

But we can still acknowledge that there are perspectives other than ours. We see objects moving around that look like what we ourselves look like -- other humans -- and suppose that they are also subjects with their own first-person perspectives. Those objects are also subjects, and that's a natural intuition almost all humans have.

It's not that far a leap to just continue with the principle that all subjects are also objects (minds are things), or even that all objects are also subjects (every thing "has a mind", at least in a sense), and so that object and subject are just different perspectives on the same (if you prefer) beings, or entities, or whatever you'd like to call them.

The important differences between different things/beings/entities/whatever is their structure and function, which are abstract features independent of any substance. From there it's a short step to treating everything as equally abstract, with concreteness merely being participation in the same structure as oneself -- to wrap back around to Wheeler. -

My Moral Label?I get what you’re saying, but it’s just difficult for me to say I believe something that I know is irrational. IOW, all of my moral actions are irrational in my view. As such, I really see no need in trying to justify them since it can’t be accomplished. That said, in practice I have general principles that I try not to violate for emotional/pragmatic reasons (guilt, punishment, undesirable outcomes, etc.). — Pinprick

I guess I'm just seeing echoes of my past self in your self-description. There was a period in my philosophical development where although I had definite opinions on a bunch of philosophical questions, regarding both reality and morality, it looked like it wasn't possible for any such opinions (mine or others') to be grounded in any way that made any justifiably better than any others, any of them anything other than just as equally baseless as anything else.

But I did eventually figure out a pragmatic basis for grounding my philosophy -- both sides of it, the descriptive side and the prescriptive side -- and since you say of yourself that in practice you disregard all of those broadly-speaking "skeptical" moral viewpoints and act on other principles instead, I feel a glimmer of hope that you too will recognize the rationality of pragmatic justification, and so be able to hold up the principles that you act on in practice as rationally justifiable principles, and not just your baseless opinions.

Something that I hope might help in that regard, which was part of my journey too, is to look into how all of the arguments for moral skepticism have analogues about reality as well, analogues that most people (probably yourself included) are much more easily inclined to refute for obvious-seeming practical reasons. Those same reasons, applied analogously against the arguments for moral skepticism, helped me to ground my moral principles on equal footing as my epistemological/ontological principles.

And my principles are heavily weighted towards what I shouldn’t do, as opposed to what I should do. — Pinprick

That is, I think, a very good principle in itself, and the moral analogue of critical rationalism, which I think is the correct epistemology. Both in deciding what to believe and in deciding what to intend, the focus is best put on avoiding the most wrong options, rather than on identifying one specific uniquely right option.

(And that right there is 25% of the way to completing the analogy between reality and morality already). -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsThat said, I don't think anyone put Trump into power. — Wayfarer

Right, I didn't mean to imply that anyone did. That's where the "useful idiot" part comes into play. They're making use of him, once he's there, but even they still see that he's an idiot, and didn't want him there in the first place. -

Who are the 1%?These resentments find root in the fallacious belief that all of economics is 'zero-sum'; that those who have accumulated wealth have necessarily obtained it by confiscation. — geospiza

One does not have to believe that all of economics is zero-sum in order to believe that theft is possible, nor that other forms of illegitimate transfers of wealth (if those somehow don't count as theft) are possible. -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsIn a way, it makes Trump look even more pathetic - manipulated by cynics for their own gain, while in his mind, they're supporting his cause. — Wayfarer

This is how I’ve always looked at Trump. He’s a loud, attention-getting, useful idiot to the people in actual power, or rather worse still, the paid puppets of those people (for the real career politicians like McConnell are in turn just the puppets of the billionaire class). He’s a puppet of puppets, doing a song-and-dance routine about how he’s got no strings, completely unaware of the irony there. The really sad part is how much of the audience actually believes that song and dance. -

My Moral Label?This is more about finding a way to answer someone who asks what morality I ascribe to. — Pinprick

From what you’ve said so far I think emotivist is the most succinct and comprehensive label for what you say you think, since it strictly entails nihilism, which strictly entails relativism and pragmatically entails egotism, usually a presumably hedonistic egotism.

But since you say that in practice you ignore all those things that you say you think, it still looks like you don’t actually think them, but just say you do. So I’d recommend instead saying that you think the things that you act like you think, and finding the right label for that instead. -

Physicalism is False Or CircularNo worries. I don't need anything in particular in response. I wasn't originally even going to post that, it was just an idle thought I had somewhere in the midst of my day, but then your John Wheeler Participatory Universe post reminded me of it, so I decided to share after all.

-

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsAlso curious is the flat out (absolutist) view that there has been no voter fraud and no irregularities. The question is why no one ever says 'yes, there were errors in counting, however these are insufficient to decide the election' — FreeEmotion

It’s because people generally cannot handle subtlety. Intellectuals discussing these things in detail should be acknowledging those subtleties, yes, but general reporting for the general public needs to bottom line it for them, because they’re not going to bother trying to understand the subtleties and will just run with their biases instead.

If it’s the case that any irregularities in the electoral process (of which there are inevitably some) are negligible in the biggest picture, then what Joe Public needs to hear is that everything is fine. Because if you tell him all the details he’ll add a bunch of negligibles up into something way out of proportion. -

Physicalism is False Or CircularThat reminds me of something I was just thinking about, with you in mind, earlier today. I was thinking about this thread, and about my own ontology, and how better to convey my ontology to you. And I thought of saying, in reference to your non-Cartesian kind of dualism, a dualism of form and substance, that my account differs in holding that there isn't a dualism there, but not by denying form as I expect you would expect. Rather, I hold that everything is formal, and the only thing that makes some forms "substantial", concretely instantiated, while others generally are not, is that they are parts of the same formal structure that we are (ourselves being entirely formal structures as well), and therefore we experience them, because we interact with them.

So on the one end of a spectrum of sorts, you have that reality in the abstract is just a formal structure. On the other end, you have that reality in the concrete is entirely experiential. These are both things you might call "mental". The physical world, the ordinary stuff with which we are most familiar, like rocks and trees and tables and chairs, is stuff in the middle of that spectrum: those are abstract structures that we suppose are a part of the abstract structure that is our world, on account of (and held to account by) our concrete experiences.

The mental-as-in-experiential and the mental-as-in-abstract are just the extreme aspects of physical things that are left once you've completely removed the other aspect: the mental-as-in-abstract is just what's left when you remove all experientiality from the (ordinarily physical) object of your consideration, and the mental-as-in-experiential is just what's left when you remove all abstraction from the (ordinarily physical) object of your consideration.

But it's still all continuous and unified with the physical, the same kind of stuff as rocks and trees and tables and chairs. The things that you might want to consider nonphysical are just the extreme ends of that continuum. -

Schopenhauer's metaphysical explanation of compassion and empirical explanations.Phenomenalism is all about understand things in general from an experiential, first-person perspective. Empiricism is specifically about understanding reality through observation, which is a kind of experience.

True, empiricism is usually paired with a universalism about reality that thus requires agreement between different first-person experiences, i.e. intersubjectivity, but nothing ever said that phenomenalism has to be entirely solipsistic, caring about only one person’s experiences and no others. -

Schopenhauer's metaphysical explanation of compassion and empirical explanations.Empiricism is a subset of phenomenalism.

-

My Moral Label?1. Nihilism- I conclude that nihilism is true due to the inability to logically justify any moral judgement (why rape is wrong, why I should help others, etc.).

2. Emotivism- I consider this to simply be factual, as evidence seems to show that we use the emotional part of our brain when answering moral questions.

4. Relativism- True because people have varying moral systems depending on culture, etc. — Pinprick

Emotivism is a theory of moral semantics. It's not just a theory that we use the emotional part of our brains when answering moral questions, but a theory that moral claims are just expressions of emotion like "boo this" and "yay that", the likes of which are not semantically capable of being true or false.

Nihilism and relativism, meanwhile, are theories of... moral ontology, maybe? About whether and in what way any moral claims are true. The former is a subset of the other, in any case; relativism is anything non-universalist, and nihilism, being radially anti-universalist, thus cannot help but be relativist.

And emotivism entails nihilism (since according to emotivism no moral claims can be true, or false for that matter), so if you just say "emotivism" then you imply nihilism and so relativism for free.

3. Hedonism- Essentially factual just like 2. It’s obvious that we avoid pain and pursue pleasure. — Pinprick

Hedonism isn't just the view that we do seek pleasure and avoid pain, it's the view that we should, and so is contrary to nihilism and thus emotivism. (But it can be of either an altruistic variety, like in utilitarianism, or an egoistic variety, like people usually assume it means; and the egoistic version is thus relativist, see below).

5. Egoism- True by default. Evolutionary pressures have led us to experience pleasure when we make choices that benefit ourselves (also, helping others oftentimes helps us as well). — Pinprick

Again, egoism isn't a view about what people do do, but what they should do. If egoism is true, then it is good for people to do what benefits them; and there is something that actually does benefit them. That means nihilism, strictly speaking, can't be true (if egoism is true).

Egoism entails relativism, though, since what is good according to egoism depends on which ego you ask.

6. Pragmatism- In life, I essentially ignore all of the above and instead just try to do whatever feels right and works for the particular situation. — Pinprick

This sounds like you don't actually agree with any of the above, since you ignore it all in practice.

I suspect what you're actually going for here is denying that there are any kind of moral facts about reality, but then in practice you still aim to do what is good. (I.e. what "works". What exactly does that mean here? There's the big question. What are we trying to do, in deciding on our moral opinions?) You just don't have any notion of how you can rigorously sort out what is good, since you can't apply the rigorous methods of sorting out what is real to morality, since morality isn't a part of reality, so you're just left with whatever you intuitively feel about it.

But maybe you could at least apply analogous methods?

I would suggest looking into non-descriptivist cognitivism, which I think will resolve that dilemma for you. It is a theory of moral semantics which holds that moral claims aren't aiming to describe facts about reality at all, much like emotivism, but that they are nevertheless cognitive claims, i.e. the likes of which are capable of being true or false in some sense or another, not just expressions of emotions that aren't even truth-apt.

This then enables universalism, but without supposing that there are some kind of weird metaphysically spooky moral features of reality that those universally true moral claims are describing. Which then leaves the question of how to tell which moral claims are true or false... but you've already got hedonism for that. It'll just have to be an altruistic hedonism, like utilitarianism, since universalism precludes egoism.

(But if you then apply the analogue of critical rationalist epistemology to that process of sorting out what's good in an altruistic hedoistic sense, you end up precluding consequentialism, as the moral analogue of confirmationism, leaving you with a kind of liberal deontology instead of straightforward utilitarianism).

values are both objective and subjective — Pinprick

Perhaps objective as in universal (i.e. altruistic), but not objective as in transcendent; and subjective as in phenomenal (e.g. hedonistic), but not subjective as in relative?

-

Physicalism is False Or CircularIt just offers a route to deciding if things are real without a care whether they are physical or not. — Coben

What does "physical" mean in that sentence? What is the metaphysical claim that (I presume you mean) empiricism isn't caring about there?

I can't think of what "physical" might even mean besides "empirically real", other than absurd guesses that don't even track natural usage of the word like "solid". (E.g. is air non-physical unless it turns out to be made of tiny solid billiard ball atoms bouncing around? If all atoms turn out to be fuzzy local excitations of omnipresent fields does that mean even rocks aren't physical?) -

Do English Pronouns Refer to Sex or Gender?Is a person who was born with female phenotype, called “it’s a girl!”, raised as a girl, identifies as a girl, engages in all of the girl gender roles and presentations, grows womanly features at puberty and identifies as a woman and keeps engaging in woman gender roles and presentations, dates men, marries one, tried to have a baby, can't, and looking into the problem discovers that she has XY chromosomes and total androgen insensitivity syndrome... actually a man?

-

MistakesI think that the common error underlying pretty much all the positions I disagree with is assuming the false dichotomy that either there must be some unquestionable answers (answers that are not to be questioned), which I call "dogmatism", or else we will be left with some unanswerable questions (questions that cannot be answered), which I call "relativism". That leads people to erring either to one side or the other of that false dichotomy, and from either of those errors stem all the other errors:

(Green is true or valid, red is false or invalid). -

Who are the 1%?As long as no one is forcing people to structure their companies this way then I'm fine with you having this preference. — BitconnectCarlos

I believe the point is that the present system is forcing the people who actually run the companies -- the workers -- to accept the management preferences of a small group of people who may or may not actually be doing any of the work of running the company. The alternative being presented is to cut out that undemocratic imposition and let the people who actually run the companies, the workers, vote on how to run the companies. -

Do English Pronouns Refer to Sex or Gender?So would you say that wanting to be different physically is not necessarily tied to gender? — McMootch

Not necessarily, no, but probably strongly correlated, much like sex and gender.

So that would mean there's:

- sex

- gender

- feelings about one's body

and none of them are necessarily connected. — McMootch

Correct, though I want to be clear that my "bearing" concept is specifically feelings about one's bodily sex, not just feelings about one's body in general. Basically, it's the feelings of what are today called "gender dysphoria" and "gender euphoria"; that's where my term "bearing" comes from, as the root "phor" means "to bear" (as in, to head in a direction, or to continue or carry on). It also makes a nice nagivational metaphor with "orientation": your bearing is the direction you're heading, and your orientation is the direction you're facing.

Your "bearing" terminology honestly sounds viable, definitely the most sensible suggestion I've heard on the topic to date. I'd be interested in hearing it fleshed out a little more. — McMootch

Thanks! My first thread on this forum was actually all about it, here:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/6768/disambiguating-the-concept-of-gender/ -

Creation/DestructionI've had this general thought as well.

Parallel to it: preservation and suppression are the same thing, stasis, non-change.

To preserve is to prevent destruction. To suppress is to prevent creation.

To mix all of these with good and bad again:

- To preserve something good is to suppress something bad.

- To suppress something good is to preserve something bad.

- To create something good is to destroy something bad.

- To destroy something good is to create something bad.

In general, to change some situation from good to bad or vice versa is to destroy one while creating the other, while to maintain a status quo of good or bad is to preserve one while suppressing the other. -

Do English Pronouns Refer to Sex or Gender?I think that a part of the problem is the failure (by everyone) to distinguish gender the social construct, like you're referring to, from feelings about one's body.

To use myself as an example, I don't particularly care how people gender me, the performativity is completely irrelevant to me, I behave how I decide is best to behave regardless of the gender associations of it. But I would very much like if my body was significantly different than it was, and if it weren't for cost and risk and irreversibility etc, if it was as easy as buying new clothes, I would "wear" a body much more like the opposite sex than what I have now, in a heartbeat.

I've been trying to propose that we use different terminology to refer to that property, which I call "bearing", than we use to refer to gender. Orthogonal to cisgender and transgender, people could simultaneously be cisphoric ("bearing to the same side") or transphoric ("bearing to the opposite side"). -

The Road to 2020 - American ElectionsExtremely narrow wins are reasonably subject to recounts. Asking for a recount on a win by a single-digit number like that is not out of the ordinary or unreasonable.

Trump is asking for more than just recounts in elections that were won by much much larger margins.

It's apples and potatoes. -

Physicalism is False Or CircularPhysicalism is basically just monism, the view that there is only one fundamental kind of stuff, and all the apparently different kinds of stuff are just different manifestations of this one kind of stuff -- and the commitment that that one kind of stuff is the kind of stuff we are most familiar with, the kind of stuff that the world around us that we ordinarily experience, rocks and trees and tables and chairs and so on, is made of.

Wayf you'll note that on my version of physicalism that includes along with it mathematicism, abstract objects like numbers are still ultimately the same kind of stuff as the physical universe, because on that account the physical universe is itself an abstract object, and all other abstract objects are empirically observable (and so physical) to any observers (if any) that are part of them (which we are not), just like our universe (of which we are a part) is to us. -

Physicalism is False Or CircularBut real seems more appropriate. — Coben

To my mind real and physical are as natural synonyms as moral and ethical. One is for description and the other for prescription. (And fun fact: “nature” and “nurture” share the same etymological relationship as “physical” and “ethical” too). -

Physicalism is False Or CircularIf you are right, what does it mean to talk of 'physical things', as distinct from just 'things'? — unenlightened

Ultimately it doesn’t mean anything different, because the supposed difference in kinds of things is a false assumption.

But this applies equally to any kind of monism, or any case of claiming that for all x, x is F. What does “F” mean if it applies equally to everything? Are we completely unable to make any universal claims without thereby rendering them meaningless? -

Physicalism is False Or CircularRegarding psychosomatic effects, it's perfectly ordinary for mental states to cause physical states: me changing my attention to a closer or further object can cause my eyes to dilate just as much as drugs could. Fear can cause my heart rate and blood pressure to increase. So it is not at all surprising that mental states of belief should effect physical states of the body in a psychosomatic way too.

All that is evidence for the mind being a physical phenomenon, not to the contrary. -

Philosophy on philosophy"A medieval university curriculum involving the “mathematical arts” of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music." (Wiki) — jgill

In modern applications of the liberal arts as curriculum in colleges or universities, the quadrivium may be considered to be the study of number and its relationship to space or time: arithmetic was pure number, geometry was number in space, music was number in time, and astronomy was number in space and time. [...] The term continues to be used by the Classical education movement [...] — Wiki on Quadrivium, modern usage section

Generally, social science is not considered a physical science. Look it up. — jgill

Generally, "social science" is not one thing, so it's not "a" anything. There are many social sciences. And they fit perfectly into the structure of this diagram. (Physics, chemistry, biology, psychology is the familiar stack; astronomy/space sciences, geology/earth sciences, ecology/life sciences, and sociology/social sciences is the parallel stack of systems versions of all those). Rename the two lower wings "descriptive sciences" and "prescriptive sciences" if that makes you happier, I don't care.

And your diagram accords philosophy an enviable position among virtually all human activities. At a time in the past that might have had merit, but I don't see it these days. Sorry, but it seems conceited and way out of proportion. — jgill

The relations between abstract things don't change over time, so whatever merit it ever has at one time, it has at all times. This isn't a diagram of how much emphasis any particular human society contingently puts on the different subjects, but of the inherent relationships between the different subjects. Abstract ones at the top, practical ones at the bottom, etc. If you wanted to distort it to reflect how much emphasis the modern western world puts on them, all the abstract stuff at the top would be shrunk way down, and the trades section at the bottom would be blown way up. But that's not the function of this image.

And the mathematical world now is far too complicated to be encapsulated so trivially in your diagram. — jgill

If you didn't notice, in addition to being an application of the quadrivium, it's also a mirror of the arts side, which has musical arts (broadly characterized as art in time), visual arts (broadly characterized as art in space), and performance arts (broadly characterized as art in time and space, including all of dance, theater, film, video, animation, and so on), as well as the linguistic arts, parallel to each of those non-linguistic arts, such as poetry (characterized as being about things like rhyme and meter, figuratively "music in words"), prose (characterized as being about vivid descriptions, figuratively "pictures in words"), and storytelling (figuratively "movies in words").

And of course down in the foundational corner, design, as in the design of things like the interfaces people use and spaces people occupy, which I hold to be the non-linguistic parallel of rhetoric itself (of which "communication" as a field is an outgrowth), being all about using style and presentation to draw people's attention in the direction the designer wants it drawn, to make some things seem obvious and intuitive while hiding other things away where they won't be noticed, and so guide people's behavior, just as rhetoric emphasizes some aspects of some parts of some ideas while deemphasizing others, and so guides people's feelings about those ideas.

Pfhorrest

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum