Comments

-

Philosopher Roger Scruton Has Been Sacked for Islamophobia and AntisemitismThe moment you converted to islam, you denied your European heritage and embraced the moslem heritage. Enjoy your moslem heritage, but please do it outside Europe. Islam is not a part of European heritage. — sunknight

You know how much of our 'European heritage' derives from ancient Islamic culture right? We're the inheritors of the Islamic Golden Age just as much as we are of Plato and Aristotle. -

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupIII. Application to Space.

Riemann takes his previous discussion and tries to relate it to physical space. Specifically, how does being able to see shapes/manifolds as 'spaces unto themselves' change what conceptions of space are possible? And how does this plurality of space concepts relate to empirical science?

He begins in §1 with a recap of the properties which characterise the geometry of an object.

§ 1. By means of these inquiries into the determination of the measure-relations of an n-fold extent the conditions may be declared which are necessary and sufficient to determine the metric properties of space, if we assume the independence of line-length from position and expressibility of the line-element as the square root of a quadric differential, that is to say, flatness in the smallest parts.

First, they may be expressed thus: that the curvature at each point is zero in three surface-directions; and thence the metric properties of space are determined if the sum of the angles of a triangle is always equal to two right angles.

Secondly, if we assume with Euclid not merely an existence of lines independent of position, but of bodies also, it follows that the curvature is everywhere constant; and then the sum of the angles is determined in all triangles when it is known in one.

Thirdly, one might, instead of taking the length of lines to be independent of position and direction, assume also an independence of their length and direction from position. According to this conception changes or differences of position are complex magnitudes expressible in three independent units.

(1) (Space is flat) if and only if (triangle angles sum together to 180 degrees). This is one way for curvature to be constant - everywhere 0.

(2) (Space has constant curvature, like a sphere surface) if and only if (the sum of angles in one triangle is the sum in all others). Note that the equivalence in (1) is also a case of this equivalence.

(3) Even weaker, if line lengths do not vary with origin point or orientation, how inter-point distances constrained to a manifold vary is always expressible as a function of the variables used in defining the manifold. (1) is a special case here since the 0 function is such a function, so is (2) since the constant function is such a function. (3) expresses the dependence of interpoint distances on the variables tracking the point on the manifold.

§ 2. In the course of our previous inquiries, we first distinguished between the relations of extension or partition and the relations of measure, and found that with the same extensive properties, different measure-relations were conceivable; we then investigated the system of simple size-fixings by which the measure-relations of space are completely determined, and of which all propositions about them are a necessary consequence; it remains to discuss the question how, in what degree, and to what extent these assumptions are borne out by experience. In this respect there is a real distinction between mere extensive relations, and measure-relations; in so far as in the former, where the possible cases form a discrete manifoldness, the declarations of experience are indeed not quite certain, but still not inaccurate; while in the latter, where the possible cases form a continuous manifoldness, every determination from experience remains always inaccurate: be the probability ever so great that it is nearly exact. This consideration becomes important in the extensions of these empirical determinations beyond the limits of observation to the infinitely great and infinitely small; since the latter may clearly become more inaccurate beyond the limits of observation, but not the former.

A discrete manifoldness is a purely categorical structure - it consists of distinct elements like A,B,C, rather than a continuum of points constrained by a function of position. I think all this is saying is that ways of counting discrete objects can error, but conceptually the procedure is quite simple - irrelevant of what the categorical structure is, counting's the same and 'to count' doesn't change meaning with respect to changes in counted elements. Measure relations of continuous manifoldness do, however, since curvature may change and thus change how measuring tapes glued to the manifold work.

In the extension of space-construction to the infinitely great, we must distinguish between unboundedness and infinite extent, the former belongs to the extent relations, the latter to the measure-relations. That space is an unbounded three-fold manifoldness, is an assumption which is developed by every conception of the outer world; according to which every instant the region of real perception is completed and the possible positions of a sought object are constructed, and which by these applications is for ever confirming itself. The unboundedness of space possesses in this way a greater empirical certainty than any external experience.

Extent probably means something similar to cardinality, or maybe a 'larger' concept. A continuum of points will have an infinite extent of points in it, since there are infinitely many, but nevertheless it may be bounded. Like the line between 0 and 1 on the number line.

Space is three dimensional, this is confirmed in every experience of it. Moreover, it doesn't 'just stop' at any point, making it unbounded (Riemann does not however seem to say why). However, Riemann portrays the unboundedness of space as 'possessing a greater empirical certainty than any external experience'. This is puzzling, on the one hand we have the unboundedness of space being supported by every experience, on the other we have that because or leading on from this unboundedness in situations of perception we can be more 'empirically certain' of this unboundedness than any mere synthesis of experiences allows.

I suspect I am misinterpreting the distinction between unboundedness and infinite extent, and both terms. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

Street, what do you think is outside of Luke's conception of 'everyday language' that he's not accounted for? And how does this excess relate to how you see your understanding of W. contrasting his? -

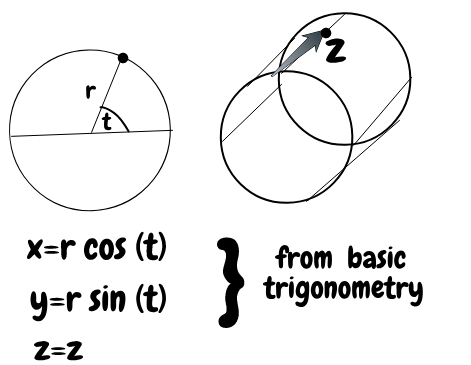

Spring Semester Seminar Style Reading GroupFor those of you wondering how all this math might apply in practice, I've got a worked example showing how the surface of a cylinder is actually flat.

The (curved) surface of a cylinder is just a circle boundary swept upwards. This means that any point on the surface of a cylinder can be given by an angle of rotation around its central axis , the distance from this central axis ; which is also the radius of its generating circle; and the distance travelled up from the circle's base .

For ease, fix and let's make the circle centred at the origin of 3D space, the point (0,0). The typical point on the rolling surface of the cylinder (with radius 1) can then be expressed as:

The curvature of the cylinder is expressible by how the rates of change of tangent planes at each point interact, which means we need to differentiate with respect to each coordinate.

The angular changes which track the changes in the tangent plane with respect to variation in coordinates are tracked by the dot product between all pairs of rates of change. IE we have:

What each equation says is that (1) differential changes in angle as they contribute to the curvature are constant, , (2) differential changes in height as they contribute to the curvature are constant as well and that (3) moving a bit around the circle and moving a bit up the circle at the same time doesn't change the curvature.

The first (1) is associated with the infinitesimal length change along alone, . The second is associated with infinitesimal length change along alone, , and the final tells you how moving around and up at the same time changes the interpoint distance - not at all.

This means that the arc-length between two points on the surface can be measured just by how much one is rotated with respect to each other and how much one is above or below the other , the sum of the rotational amount and the distance up gives the infinitesimal change from one point to another. IE:

which is actually a flat metric. Thus, since a coordinate system exists which renders the arc-length between nearby points an independent function of each position, the surface of a cylinder is actually flat in the intrinsic sense. -

Philosopher Roger Scruton Has Been Sacked for Islamophobia and AntisemitismScruton's always interesting because he engages in cultural critique from a conservative perspective without being reductive or otherwise batshit insane. He's obviously not an outright racist in the 'I don't like the Jews or the Muslims' sense, and even if it is true that his conservatism is allied with systemic injustices, he shouldn't be martyred over it.

I imagine that no one was actually offended by what he said, but the potential for what he said to be found toxic or prejudiced (even if being done in a smear job) was what got him ousted. I'm, ironically maybe, reminded of Zizek here; we don't have to be of the opinion that what he said was toxic in order to believe that it is - we simply need to defer belief to our community, they may find it toxic, they will find it toxic, so it is - nevermind what we think about it. -

Who is the owner of this forum...This isn't about feedback or site policy any more, I'm closing it.

-

The VillainGeneral rule:

If you have concerns about another member it's a lot more polite to PM a mod about it than bring it all out in public. Especially considering we're the ones that have to call whether action is appropriate and what the action should be. You're being needlessly provocative.

I'll close the thread. -

Who is the owner of this forum...

There are a list of topics that draw people to philosophy, god/atheism, ethical problems like the trolley problem, solipsism. Even if you're personally bored of the discussions, this is still a space for people to play them out. Content's never an excuse to be rude, flame, etc. though everyone gets heated sometimes. -

Who is the owner of this forum...The only thing I can see as a viable tactic is to gently point out the repetitive behavior, and when that fails, move on and ignore the offenders. — NKBJ

If you believe someone is behaving badly, you can PM a mod and we'll look into it. -

The West's Moral Superiority To IslamYou know what, you actually think there's a rape culture in Australia, I am done wasting my time talking to you. Fxdrake or whatever his name is, another mod on this forum is a similarly poor thinker who utilises unreasonable, hostile interpretations for political leverage, just like you. I can't help but think there is an explanation but maybe it's just a coincidence. — Judaka

That's me! :D -

Who is the owner of this forum...

Report anything you deem report worthy, we make the executive decision (we get an automatic prompt when there's stuff reported we've not made a ruling on). -

Who is the owner of this forum...Alas, I cannot. — DingoJones

In lieu of there being a perfect definition, I suggest we continue bodging along as we always do. -

Who is the owner of this forum...

As S. said.

Personal view of it:

Some cases of spam are really easy to classify, some are just benign but largely inarticulate and irrelevant posts, sometimes it's difficult to see if someone is intentionally spamming and derailing threads or if they're just bad at English or have a particularly fire and brimstone inducing perspective. This applies to Christian evangelists as much as it applied to a (relatively) recent case of an incredibly angry post-colonial critical theory poster.

I don't think we punish people for having strong opinions or approaching philosophy from an entrenched perspective. There have been times where we have banned easy to anger hawkers of pseudoscientific woo, but we also often don't clamp down hard on woo or misinformed posters because, well, the minimum standard of scientific competence should probably be lower here than on physicsforums or stackexchange.

All in all, you're probably not going to get a clearcut definition of spamming or evangelism which sorts posts and posters into the right categories 100% guarantee every time; partly because it's not necessary for staff to effectively curate content, and partly because doing such a thing is an exercise in futility.

If you can give us a perfect definition of spam or evangelism as it is relevant to moderating the board, I'm all ears though. -

Who is the owner of this forum...I'll calm down now...and just ignore S. — Frank Apisa

If you and someone don't get along on here it's usually best to ignore them.

I will do my best to be a decent contributor. — Frank Apisa

Thanks.

I had a look at the discussion between you and @S, just looks like it got heated. There were parts of your posts of questionable relevance to the discussion topics, which S reacted to with the spam accusation. If I've read it right with my skim read anyway.

Doesn't seem like much of a scene is required, it's not like you merc'd each other in a rap beef fam. -

Who is the owner of this forum...

List of staff, including who is online, the little face in the top right corner of our poster icons indicates that we are staff. @jamalrob is the owner and has been summoned to the thread.

If your issue concerns treatment from other members, including mods, you are free to personal message any mod and we can try and deal with whatever interpersonal problem that there is. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Note how frequently in the passages between 66 and 78 (and elsewhere as well) he not only says "compare" but makes comparisons. It is this method of comparison that is of central importance. There is a clear connection with questions of language, but if one is looking for an übersichtlichen Darstellung, a representative overview or surveyable representation or perspicuous representation, then limiting the comparison to linguistic matters foreshortens one view. The Tractarian distinction between seeing and saying is still at work here, although it functions differently. — Fooloso4

I did not mean to suggest otherwise, to the bolded statement. Wittgenstein's analysis of language in the PI always has a certain context (behavioural, social, game-inspired, later perspectival) in mind, and the context varies over the examples he uses. He uses the examples to reveal general features of language use, and portraying the commonalities between them is as much his 'method' of analysis as it is the bulk of our exegesis of the text. His emphasis on examples is what I was trying to ape by using the example of propositional logic - to highlight what it leaves out, and what a view from it looks like. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Also consider 'removing the spectacles' as a non-logical operation, that is, it doesn't follow the internal structure of the domain of concepts obtained by peering at a topic through rose tinted glasses, it rather reframes them for other inquiry; which Wittgenstein likens to description or 'looking around'. The end of the first paragraph of 108 fits in well with this interpretation:

(from 108) The preconceived idea of crystalline purity can only be removed by turning our whole examination round. (One might say: the axis of reference of our examination must be rotated, but about the fixed point of our real need)

eg, the idealised language philosophy criticised doesn't 'pivot' around any adequate apperception of the structure in language. In my example, what is determinative for propositional calculi is a filtered representation of the elements of language and their relationships in argument; there's no room for questions, doubts, beliefs, appeals to emotion, reframing attempts and so on, because they are excluded from the 'philosophical grammar' applied to language through the rose tinted glasses. What was excluded from the logical artifice of 'crystalline purity' was the broader structure of language and behaviour; ratiocination in this realm of purity consists in the production of well formed formulae - none of which can be questions, reframing attempts, metaphors, analogies or appeals to structural similarity.

By treating the means of representation of propositions and their logic as the idealised representation of propositional calculi (or the more general one in the Tractatus), much of the world becomes thought of only in category errors - how can any expression have sense if it does not resemble only those things which were posited to?

There's probably an interesting analogy to Kant here, with regard to transcendental illusions.

Kant identifies transcendental illusion with the propensity to “take a subjective necessity of a connection of our concepts…for an objective necessity in the determination of things in themselves” (A297/B354). Very generally, Kant’s claim is that it is a peculiar feature of reason that it unavoidably takes its own subjective interests and principles to hold “objectively.” And it is this propensity, this “transcendental illusion,” according to Kant, that paves the way for metaphysics. — SEP

Wearing the 'rose tinted glasses' or the 'spectacles' invites us to see 'the connection of our concepts' (in the ideal domain of an abstract logical language) as of 'objective necessity in the determination of things in themselves' (the rough ground of ordinary language)- rather than as a limitation of the vantage point we viewed 'the things' (language) from.

In the version I've been using, just below 109 is the comment:

"Language (or thought) is something unique"—this proves to be a superstition (not a mistake!), itself produced by grammatical illusions.

the inappropriate substitution of our conceptual links and tokens within an account for the real structure of the desired topic is exactly the logic of seeking such an 'ideal' and therefore seeing it everywhere; it is not a simple mistake, the conceptual structure of ideal language is very rigorous and its internal links are self consistent - but the endeavour of trying to picture language (and language as a picture) in this way is misguided when dealing with all the ambiguities and subtleties of the huge scope of natural language. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.

I think 104:

We predicate of the thing what lies in the method of representing it. Impressed by the possibility of a comparison, we think we are perceiving a state of affairs of the highest generality,

should be read in the context of 101->103, and the broader context of Wittgenstein's critique of idealised approaches to language. I think 'we predicate of the thing what lies in the method of representing it' is fleshing out how we 'find' the ideal in language in the sense of 101:

101. We want to say that there can't be any vagueness in logic. The idea now absorbs us, that the ideal 'must' be found in reality. Meanwhile we do not as yet see how it occurs there, nor do we understand the nature of this "must". We think it must be in reality; for we think we already see it there.

our 'absorption' in the problematic of a pure philosophical language of expression, or a universal logic, invites us to 'see' or 'perceive' (note the two perceptual terms in 101 and 104!) the linkage between 'the thing' and 'the method of representing it' as logically prefigured/framed in terms of such an ideal language. Specifically, this ideal logical structure is posited 'of the thing' through 'the method of representing it', and this positing opens (and invites exploration of) a 'background' for us to uncover (under the problematic of idealised logic/language):

102. The strict and clear rules of the logical structure of propositions appear to us as something in the background—hidden in the medium of the understanding. I already see them (even though

through a medium): for I understand the propositional sign, I use it to say something.

I read it like the 'background' and 'the method of representing it' are collapsed into logical formalism by this 'idealised language' interpretive habit that Wittgenstein diagnoses of philosophers. But the link between the two isn't interpreted as a logical or rational pivoting about a concept, the link is 'seen' -or posited prior to inquiry- through the drive to abstract/ideal logical formalism. Wittgenstein likens this drive towards the ideal in 103 to putting on a pair of spectacles:

103. The ideal, as we think of it, is unshakable. You can never get outside it; you must always turn back. There is no outside; outside you cannot breathe.—Where does this idea come from? It is like a pair of glasses on our nose through which we see whatever we look at. It never occurs to us to take them off

I think a more precise metaphor would be rose tinted glasses, where 'seeing things in a rose tint' is a constraint placed on philosophical discourse to idealise/abstract towards logical formalism capturing the 'essence' of language. The 'essence' of language, the ideal of it, plays the role of the inescapable rose colour implicated in seeing all things; but no argument demonstrates that all is rose tinted, it's 'put there' by one's style of philosophical thought. For one who believed that all philosophy requires arbitrarily donning such glasses; that philosophy begins with a confused and limited apperception;, it is not surprising that they would reject the entire enterprise.

Edit: perhaps another good analogy is this:

show that to someone who hasn't learned to process propositions in logical syntax and it wouldn't mean a damn thing. We have to 'learn to see' the connections between natural language argument forms and the modus ponens. The 'representation' of our argument forms (in terms of validity, soundness, truth functionality and so on) consists in fabricating rules for propositional calculi spurned on by real argument patterns, and then we may say that the above formula is modus ponens. Even someone who understood how to argue using the modus ponens syllogism would not necessarily immediately 'map' it to the representation of it in the theory. We have to do a lot of conceptual prefiguring to analogise reasoning with a logical calculus; and if we 'see' language as logical in the sense of a calculus, this consists in a 'comparison' of the thing (modus ponens argument forms in natural language) with its means of representation (the above formula) - a good fit between the two invites us to study more. Even though we had to lose a lot of the structure of arguments to 'reveal' their propositional form. Thus the revelation is, too, of a constrained domain of concepts; reading back the means of representation into the thing we represented using them always suggests 'depth' in the sense of a background to explore; why is it that arguments bear a relation to the notion of truth functionality? Why is it that meaningful languagein propositional calculusconsists of truth functions of propositions? There is always the danger of forgetting the constraints or simplifications we take to embark upon an inquiry when we discover a 'background' which underlays everything within the constrained conceptual space whose boundaries are those set by our inquiry. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityThat's what I've been discussing with andrewk, whether EM waves are real waves or not. Andrewk insists that "wave" is defined in physics in such a way that a medium is not required for a wave. But this is contrary to the Wikipedia page on waves in physics, and contrary to what I learned in high school physics, as well. I think andrewk is just fabricating a definition to support an ontological position, and asserting the correctness of that intentionally directed definition. — Metaphysician Undercover

Nah man. He ain't duping you bro. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective reality

Think that's how it happened. Michaelson-Moorley? Michaelson-Morley, was linked by andrewk earlier in response to MU IIRC. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityIt's worth noting that superpositions have been created for objects with up to trillions of atoms (as in the case of the piezoelectric "tuning fork"). Probably most physicists would consider QM to be a universal physical theory (i.e., applicable to everything). Which is part of the point of the Schrodinger's Cat and Wigner's Friend thought experiments. — Andrew M

So you see it like - everything is a quantum system, just sometimes the corrections from quantum mechanics to macroscopic systems are sometimes negligible? Not that there is a particularly strong divide between macroscopic and quantum. -

Killing a BillionHey which people are more valuable? I will kill everyone subject to the whims of my blind prejudice.

-

Why do some members leave while others stay?Or straw men appears from such practices. — Wallows

It isn't even necessarily a straw man; just the distinction between recognising internal consistency or inconsistency vs consistency or inconsistency with already held opinions or interpretive habits. EG, you're not going to get particularly far into Philosophical Investigations if you read everything through the lens of 'language = sound pulses or marks which represent mental content' or particularly far in a discussion of infinity if you don't know how limits, continuity or convergence work in context (to use two recent-ish examples from the board). -

Why do some members leave while others stay?But success in what? — Wallows

Depends on what you're writing. For purely exegetical work, you should go through the arguments in the text in as close to the text's terms as possible; broadly, explaining each moving part of the argument and how it relates to the goals of (that part of) the text. There should be a structural mirror between your exegesis of the text and its content.

This might seem trivial, but it's actually pretty hard to stay relevant/text-focussed and exegetical at the same time; it usually requires suppressing immediate criticism of the text using concepts or viewpoints foreign to it. It's a lot easier to have an opinion about something than detailed knowledge about it, largely because it's easier to form beliefs (in metanarratives about the text) than grow knowledge (of a text's inner workings). -

Why do some members leave while others stay?

Reading groups are a lot of effort to stay close to the text and provide useful exegesis. If you wanted yours to succeed, you could have put in more effort.

Also, life happens, and reading groups take a lot of effort and time which compete with other activities, often necessities, like work. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityHave a question for people who know a lot more about this kind of thing than me.

I've seen that people use the word 'know' a lot when talking about observation/information transmission/interactions involving energy exchange, but 'know' looks to be used in different contexts to where just 'correlation' would be appropriate - like, if 2 particles are entangled, it doesn't seem typical to say that one particle 'knows' the state (distribution) of the other. Examples in this thread are the use of 'Alice knows that Bob knows...' towards the start in the discussion between @boundless, @noAxioms and @Andrew M.

What do you mean when you use 'know' in this sense? What is the (range of appropriate) physical interpretation(s) of it, if it has one? -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityI really believe that you don't see the problem. One of the things Bohr said, and it's a bona fide quotation, is that 'Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not understood it.' And I don't think you see anything shocking about it - ergo ... — Wayfarer

I'm not the one advancing an incredibly contentious idea about quantum mechanics requiring human minds to work. Note, this is not just the claim that humans can act as observers; but that only humans can act as observers. I'm indifferent to the matter of whether we can, but strongly convinced that other things can observe too; as is consistent with everything we've read in the thread and referenced. Moreover, I believe that if human consciousness can act as an observer, our sentience will have much less to do with that than the fact that our consciousness comes equipped with systems of macroscopic objects in our bodies.

The claim that only humans can act as observers, conversely, is inconsistent with everything we've read. Perhaps you should be more surprised; your view is inconsistent with the sources you used to form it.

Another Bohr quote is that 'a thing does not exist until it's measured'. The Wheeler 'Law without Law' article draws on the same point, where it says 'a phenomenon is not a phenomenon until it has been brought to a close by an irreversible act of amplification'. OK, this might be a photographic plate or some other device, but in all cases, the act of measurement or observation is intrinsic to it. — Wayfarer

This is extremely inconsistent with the claim that only humans can act as observers. Lab equipment also, trivially, works. And I do not believe you think lab equipment is sentient. The only way I can make sense of your claim now is that you believe that something being a derivative of human action imparts it observer status; but this thereby means non-human things can be observers.

Is your claim that observing objects must be derived from humans or be humans, or is your claim that only human consciousness can be an observer?

But look at the definition of 'device': "a thing made or adapted for a particular purpose, especially a piece of mechanical or electronic equipment". Devices are made by an observer, to complement or supplement the natural senses, and their operation and raison d'être are entirely dependent on the observer. And, as I noted already, 'data' does not become 'information' until it is interpreted in a context - until someone is informed by it. An automatic weather station contains only data, which do not become information until they're observed. — Wayfarer

This is irrelevant to whether lab equipment, or other physical processes, can act as observers. It's also inconsistent with the notion that probability distributions have entropy notions derivable from them. If anything, the 'data' comes after an 'informational' relation obtains between a system and an observer. A pair of electrons can be entangled with each other, thus giving information about the other's state, but they could also be in superposition prior to measurement; data derives from observing the state (or superposition) of something, not just having information about it. You'v got things the wrong way round here; information is much weaker than data.

Yes, quantum physics does suggest 'subjective idealism'. Hence the controversy! But that is not exactly news - Sir James Jeans and Arthur Eddington both wrote books on it between the wars ('the universe seems more a great mind than a great machine'). Paul Davies and other science writers have been commenting on it for decades - I read 'The Matter Myth' in, oh, about 1989. — Wayfarer

Except no, it doesn't, and the role consciousness and ideas play in quantum processes has been declared either irrelevant or non-central in every single source we've read in the thread. Also note 'seems like' in the quote, it would not surprise me if this was another analogy you have misinterpreted.

All of the arguments that are being deployed here are specifically to avoid the implication of the role of the observer which seems the unavoidable inference. But many think it's solved, or that it's a non-problem, because of 'presumptive realism', which is that 'common sense simply insists that the Universe exists when we're not observing it. Everyone know this is true.' But this is precisely why Bohr said that 'quantum mechanics is shocking'. This is why Einstein felt compelled to ask the question about 'does the moon continue to exist when we're not looking at it?', and why Einstein and Bohr went on to debate the point for 30 years. — Wayfarer

You continue to display a deaf ear for metaphor, and we've covered this. That quote is intended to be a reductio on the claim that observers constrain or realise quantum system dynamics; Bohr did not think that only human consciousness could be an observer, and he disagreed with Einstein in that debate not because Bohr thought only humans could be observers, but because he thought (rightly) a proper account of quantum phenomena requires one to tackle observer dependence. You have mistaken Einsten's exaggerated caricature of Bohr's position for Bohr's position (which has been revealed previously by looking at quotes from Bohr, he took something close to a relational view around the time).

The initial philosophical problem has never been solved, it's simply been continually obfuscated. What I'm arguing is that there is an irreducible subjective element to all science and all observation, which is the constructive (in the Kantian sense) activities of the mind. 'Modern thought' believes that it has bracketed this out by arriving at a purely quantitative and completely impersonal description of the Universe - the so-called 'view from nowhere'. However physics shows us that even the view from nowhere is still a view, and that a view requires a viewer. But people would rather believe in an infinite number of parallel universes than face up to it. — Wayfarer

Ah yes, that unforgettable Kantian thesis, subjective idealism. It is almost as if he never argued against subjective idealism in the Critique of Pure reason.

Information = data, measurement = conception = observation, empirically real = subjectively ideal, misrepresenting all the sources we've analysed together in the thread, presuming that I'm some ancient Cartesian and responding as such. grumble grumble

If you read me with more care you'd see that while yes, I'm a materialist of some sort, but I have strong sympathies for the relational interpretation of QM. IE; I fully agree with you that observers and systems need to be considered together. This is the grand charge you're saying I don't understand, but the relational character of nature is something I think is very important to see. You just think that I don't understand the issues here because I'm not using the above series of equivocations.

Though, I don't claim to be an expert on quantum mechanics. -

You're not exactly 'you' when you're totally hammeredYes, but it's not that simple. Being so drunk or high that you're not exactly you is a mitigating circumstance. This actually happened to me as recently as last Friday. I was so drunk that I wasn't myself to extent that I caused a big commotion which resulted in shouting and arguments and the police being called. Some of the people involved later tried to get revenge. I caught them and confronted them, and I apologised for my behaviour the other night, but emphasised that I was drunk out of my face, whereas they are both stone cold sober, and I could instantly see the shame on their faces when I said that. — S

Mitigating circumstances don't remove responsibility, they only make transgressions easier to understand, forgive, or not care about. Something seen as a small transgression is more likely to be forgiven. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective realityIsn’t that the very kind of question that the article in the OP addresses? That two observers observing what ought to be the same event each see something different? — Wayfarer

It depends, I think you keep reading it that an observer is required to be a human and measurement

is a form of conceptualisation. I also think you believe that conceptualisation is how a human consciousness intervenes in quantum processes. You also seem to argue for 'X exists requires that X is conceptualised' through a largely transcendental idealist perspective - even though the point you're seeking to demonstrate is much closer to subjective idealism, and you're using an empirically realist conception of scientific methodology to do all this.

This is a self reinforcing collection of equivocations. For example, one moment of it is that evidence for only humans being observers is read into the supporting articles you provide by your interpretation of the word 'subjective' being necessarily associated with consciousness. This is even rejected in the paper discussed by the OP (as well as all the other articles we've discussed).

Before we describe our experiment in which we test and indeed violate inequality (2), let us first clarify our notion of an observer. Formally, an observation is the act of extracting and storing information about an observed system. Accordingly, we define as observer any physical system that can extract information from another system by means of some interaction, and store that information in a physical memory. Such an observer can establish “facts”, to which we assign the value recorded in their memory. Notably, the formalism of quantum mechanics does not make a distinction between large (even conscious) and small physical system, which is sometimes referred to as universality. Hence, our definition covers human observers, as well as more commonly used nonconscious observers such as (classical or quantum) computers and other measurement devices—even the simplest possible ones, as long as they satisfy the above requirements.(not uniquely human - me)

We both agree on the data, I don't agree with your equivocations, and I don't agree with the strategy you use that paints me as disagreeing with the data (or that the arche-fossil argument is refuted through it) while substituting your idiosyncratic interpretation of the terms in the data for its results; all the while reserving a primordial realm of meaning for philosophical contemplation which isn't touched by the 'mechanistic', merely empirical, inquiry of science. Can't have it both ways. -

You're not exactly 'you' when you're totally hammeredWe are still responsible for the stupid shit we do while drunk or high.

-

Extract from Beyond Good and Evil (para. 5)A passage dealing with ideas of “will” and “self”.

Philosophers are accustomed to speak of the will as though it were the best-known thing in the world; indeed, Schopenhauer has given us to understand that the will alone is really known to us, absolutely and completely known, without deduction or addition. But it again and again seems to me that in this case Schopenhauer also only did what philosophers are in the habit of doing he seems to have adopted a POPULAR PREJUDICE and exaggerated it. Willing-seems to me to be above all something COMPLICATED, something that is a unity only in name—and it is precisely in a name that popular prejudice lurks, which has got the mastery over the inadequate precautions of philoso- phers in all ages. So let us for once be more cautious, let us be ‘unphilosophical”: let us say that in all willing there is firstly a plurality of sensations, namely, the sensation of the condition ‘AWAY FROM WHICH we go,’ the sensation of the condition ‘TOWARDS WHICH we go,’ the sensation of this ‘FROM’ and ‘TOWARDS’ itself, and then besides, an accompanying muscular sensation, which, even without our putting in motion ‘arms and legs,’ commences its ac- tion by force of habit, directly we ‘will’ anything. Therefore, just as sensations (and indeed many kinds of sensations) are to be recognized as ingredients of the will, so, in the sec- ond place, thinking is also to be recognized; in every act of the will there is a ruling thought;—and let us not imagine it possible to sever this thought from the ‘willing,’ as if the will would then remain over! In the third place, the will is not only a complex of sensation and thinking, but it is above all an EMOTION, and in fact the emotion of the command. That which is termed ‘freedom of the will’ is es- sentially the emotion of supremacy in respect to him who must obey: ‘I am free, ‘he’ must obey’—this consciousness is inherent in every will; and equally so the straining of the attention, the straight look which fixes itself exclusively on one thing, the unconditional judgment that ‘this and nothing else is necessary now,’ the inward certainty that obedience will be rendered—and whatever else pertains to the position of the commander. A man who WILLS com- mands something within himself which renders obedience, or which he believes renders obedience. But now let us no- tice what is the strangest thing about the will,—this affair so extremely complex, for which the people have only one name. Inasmuch as in the given circumstances we are at the same time the commanding AND the obeying parties, and as the obeying party we know the sensations of con- straint, impulsion, pressure, resistance, and motion, which usually commence immediately after the act of will; inasmuch as, on the other hand, we are accustomed to disregard this duality, and to deceive ourselves about it by means of the synthetic term ‘I”: a whole series of erroneous conclusions, and consequently of false judgments about the will itself, has become attached to the act of willing—to such a degree that he who wills believes firmly that willing SUFFICES for action. Since in the majority of cases there has only been exercise of will when the effect of the command— consequently obedience, and therefore action—was to be EXPECTED, the APPEARANCE has translated itself into the sentiment, as if there were a NECESSITY OF EFFECT; in a word, he who wills believes with a fair amount of cer- tainty that will and action are somehow one; he ascribes the success, the carrying out of the willing, to the will itself, and thereby enjoys an increase of the sensation of power which accompanies all success. ‘Freedom of Will’—that is the expression for the complex state of delight of the person exercising volition, who commands and at the same time identifies himself with the executor of the order— who, as such, enjoys also the triumph over obstacles, but thinks within himself that it was really his own will that overcame them. In this way the person exercising volition adds the feelings of delight of his successful executive instruments, the useful ‘underwills’ or under-souls—indeed, our body is but a social structure composed of many souls—to his feelings of delight as commander. L’EFFET C’EST MOI. what happens here is what happens in every well-constructed and happy commonwealth, namely, that the governing class identifies itself with the successes of the commonwealth. In all willing it is absolutely a question of commanding and obeying, on the basis, as already said, of a social structure composed of many ‘souls’, on which account a philosopher should claim the right to include willing-as-such within the sphere of morals—regarded as the doctrine of the relations of supremacy under which the phenomenon of ‘life’ manifests itself.

- Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche

All thoughts and comments welcome. Enjoy! :) — I like sushi

Merged from previous thread. -

Quantum experiment undermines the notion of objective reality

How does this work? Do you think the observer's intention somehow acts on a superposition to constrain it - tightening the distribution of states or collapsing it to a single one? -

All A are B vs A are B. Is there a difference?Probably contextual, the presence of a universal quantifier like that doesn't do strictly the same thing every time to every utterance.

'Food is good' could be said after a meal, but 'all food is good' might be too strong; the utterer would probably not enjoy having their pet served to them. 'Wo/men suck' can be said to vent frustration about a partner or strange experience, but does not entail having a negative opinion of all men or women. Such utterances can be vehicles for opinion in the same sense 'Fuck off' might mean 'Leave now' or 'I don't believe you' depending on the context.

Conversely, 'people die', 'girls have uteruses' probably do express the same things as 'all people die' and 'all girls have uteruses' in most cases.

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum