Comments

-

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).

Yeah. I agree that it's a more precise translation. My motivation for translating the ~B as withholding belief or suspending belief was to highlight the contrast between it and B~; both can be translated as 'doesn't believe' and it depends on the context which means which. Equating the two is an error made tempting by 'does not believe' meaning both in ordinary language. There are good reasons to maintain that they are distinct despite this, however. -

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).~B(Ex~P(x)) <-> B(~Ex~P(x)) <-> (B(AxP(x))

Do you agree with that holding when B~ <=> ~B (abusing notation)? -

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).

They're different.

~B(Ex~P(x))

~ExB(~P(x))

Agent withholds belief that there is an X which is not P.

There is no X which A does not believe is P. -

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).Another crazy thing occurs if you introduce quantification.

~B(Ex~P(x)) <-> B(~Ex~P(x)) <-> (B(AxP(x))

"The agent withholds belief about whether there exists an entity without property P"

iff

"The agent believes every entity has property P"

I lack belief in some things which are not gazoompas. Therefore I believe everything is a gazoompa.

I think we can see that lack of belief and disbelief are different now. -

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).Also, collapsing B~ and ~B kinda removes the point of it being a modal operator...

-

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).

No... I wanted to show that not believing in a disjunction implies believing in the negation of each disjunct. This is very strange behaviour, and is implied by the OP.

1. There are <10000 asteroids around Saturn.

2. There are 10000 asteroids around Saturn.

3. There are >10000 asteroids around Saturn.

I believe in (1 v 2 v 3). I don't believe in (1 v 2), that doesn't mean I believe that ~1 &~2, since that commits me to 3. I suspend belief in each disjunct while believing the disjunction as a whole is true (it's a tautology). -

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).Also counter models. In a universe of discourse with at least one non-agent ~B can't be equivalent to B~ as ~B is true for non-agents but B never is.

-

~Bp <=> B~p (disbelief in something is the belief of the absence of that thing).

Is a bit counter intuitive.

Bob: 'I don't believe in anything you said'

Alice: 'Why?'

Bob: 'Because the first thing you said was wrong' -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

I actually don't know what Marx thought, beyond popular reports, which are clearly ambiguous. My point is that, absent clarity at the start, you're most likely to set out on the wrong path, which means you're neither getting to your destination, nor knowing where you've got.

You'd probably get quite a lot out of reading Volume 1 of Das Kapital. Not necessarily for the economics, anthropology or social commentary, but his methods of reasoning are very instructive of another way of doing things. David Harvey has an excellent lecture series on the topic and puts a lot of effort in portraying the way Marx reasons.

One of the distinguishing features of philosophy is that part of its conceptual apparatus is in coming up with and clarifying concepts while also refining them in response to questions. Moreover, the questions can help you refine the concepts, and the concepts can help you refine the questions. The interplay between the two can give rise to an organic development of your understanding as you read along or try to express your own positions. When done well, philosophy chases a theme to its roots and provides an atlas of a conceptual landscape. When done poorly, it focusses more on the classification of problems into pre-developed categories which explicate nothing insightful about the chosen theme. Exposition over imposition, always.

If beginning with definitions is required, rather than beginning with problems and orienting our thoughts towards them, this produces a tyranny on philosophical discourse. The fungibility of close-but-inequivalent words; how meaning rolls from letter to word to sentence to passage to the text as a whole; is necessary for the coalescence of refined concepts relevant to their problematics in the first place. Philosophy takes place on the interstice of ambiguity and clarity, it loses most of its content when circumscribed fully in either of those domains.

New knowledge arises out of taking radically different conceptual blocs, rubbing them together and making revolutionary fire -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)

I don't see any intellectual cowardice on Benkei's part. It's just short-hand reference to Marx's lack of belief in a god.

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower. The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself. — Marx, Critique of Philosophy of Right

You can see some atheist humanism in him, at least in this Critique. He speaks interestingly frankly in criticism about secular humanist (roughly, atheist socialism 'fraternity of man' style thing) ideals and about communism raised to the status of divinity in a letter to Ruge, usually given the title "The Relentless Criticism of All That Exists":

Therefore I am not in favour of raising any dogmatic banner. On the contrary, we must try to help the dogmatists to clarify their propositions for themselves. Thus, communism, in particular, is a dogmatic abstraction; in which connection, however, I am not thinking of some imaginary and possible communism, but actually existing communism as taught by Cabet, Dézamy, Weitling, etc. This communism is itself only a special expression of the humanistic principle, an expression which is still infected by its antithesis – the private system. Hence the abolition of private property and communism are by no means identical, and it is not accidental but inevitable that communism has seen other socialist doctrines – such as those of Fourier, Proudhon, etc. – arising to confront it because it is itself only a special, one-sided realisation of the socialist principle.

And the whole socialist principle in its turn is only one aspect that concerns the reality of the true human being. But we have to pay just as much attention to the other aspect, to the theoretical existence of man, and therefore to make religion, science, etc., the object of our criticism. In addition, we want to influence our contemporaries, particularly our German contemporaries. The question arises: how are we to set about it? There are two kinds of facts which are undeniable. In the first place religion, and next to it, politics, are the subjects which form the main interest of Germany today. We must take these, in whatever form they exist, as our point of departure, and not confront them with some ready-made system such as, for example, the Voyage en Icarie. — Relentless Criticism... Marx -

Putin Warns The West...

-

Laws of NatureThere are things about force as a concept -as a real abstraction- which make it highly amenable to analysis with vectors. Fundamentally, this comes down to motion having a direction as well as a magnitude. A vector just is a quantity with a direction and a magnitude, and a force describes a propensity to shunt with a given strength in a given direction - the same is true of the more abstract force fields which ascribe a strength of movement and a direction to points in space.

If changes in motion are equivalent to changes in direction and changes in a magnitude, is it then surprising that a mathematical language that allows us to relate changes in direction and changes in magnitude to other changes in direction and changes in magnitude allows for the description of motions in general?

Forces enter the picture as what drives changes in motion. This is a restatement of Newton's first law.

Forces add as vectors - changes in direction and changes in magnitude interact together as vector changes - this is essentially Newton's second law - multiply the changes induced in motion by vectors (see law 1) by the mass of the changing thing (or the mass as a function of time, or the mass as a function of momentum and energy) and you get the full statement of it.

Newton's third law is what interprets forces as body-body interactions, specifically a force projecting from A to B induces/is equivalent (in magnitude but opposite direction) from a force projecting from B to A. This is the same as saying that the relative position vector from A to B, is equal to

Newton's laws aren't just formal predictive apparatuses like (most) statistical models, they're based on physical understanding. They aren't just mathematical abstractions either, the use of mathematics in physics is constrained by (as physicists put it) 'physical meaning'.

The mathematics doesn't care that the Coulomb Force law (alone) predicts that electrons spiral towards nuclei. The physics does. -

The Threshold for Change

That's how weather prediction works. People fit complicated models of atmospheric pressure changes, correlate it to statistical summaries of current temperatures and evolve the system forward in time from a range of initial conditions (similar things to the current temperature/pressure measurements, elevation, distance from the sea etc), so when they say '80% chance of rain' - they mean '80% of the models we ran had rainfall in this area'! -

The Threshold for Change

I had nothing to do this evening, so:

Big difference between chaotic systems and stochastic systems. Chaotic systems are typically (as a matter of definition) deterministic, chaos occurs when small changes in initial conditions produce big changes in long term dynamics. A dynamical system, mathematically, is formed by the repeated application of a function to a set of initial conditions (numbers).

The classical example is the logistic map, which is defined by:

Imagine . And set as the starting point.

(this code works in the open-source programming language/statistical software R)logisticmap=function(x0,n,r){ xseq=rep(0,n) xseq[1]=x0 for(i in 2:n){ xseq[i]=r*xseq[i-1]*(1-xseq[i-1]) } return(xseq) }

this takes a number and spits out a number , then it takes and spits out a number ...You can go on forever.

Finding the 10th term of the sequence with that is...

that's about -6000.

Now I'm gonna subtract 0.0002 from and see how the system evolves, it has tenth term:

that's just under +1.

Four orders of magnitude different, and of opposite sign. The situation gets worse when you take more terms. This sensitivity to initial conditions is what characterises (deterministic) chaos.

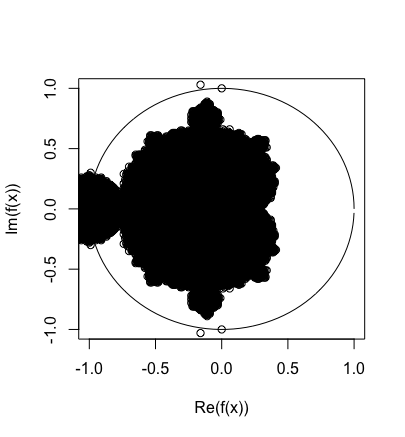

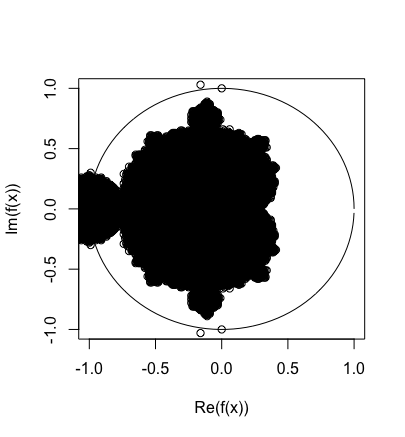

Certain functions have interesting patterns in them, it's possible to 'get stuck' in a repeating sequence or part of the set of possible values for the system. The places you get stuck in are called attractors. The classical example of this is the Mandlebrot set.

The Mandlbrot set is the set of all points in the complex plane that don't escape to infinity under the map:

This set of functions will let you generate approximations to the Mandlebrot set in R:

znorm=function(complexno){sqrt((Re(complexno))^2+(Im(complexno))^2)} mandlebrot=function(c,n){ k=1 z=0 thenorm=0 while(k<n && is.finite(thenorm)){ z=z^2+c thenorm=znorm(z) k=k+1 } return(is.finite(thenorm)) } mandlevec=Vectorize(mandlebrot,vectorize.args = "c") cs=seq(-2,2,by=0.01) cs=expand.grid(cs,cs) complexes=complex(real=cs[,1],imaginary = cs[,2]) truefalse=mandlevec(c=complexes,n=100) xs=cs[,1][truefalse] ys=cs[,2][truefalse] points(xs,ys)

which gives you the pretty picture:

of the central cardioid of the Mandlebrot set inside the unit circle.

The Mandlebrot set (strictly speaking) is not a strange attractor - but it gives off the intuition of one. A complicated fractal structure implicit in the geometry of a dynamical system. The attractor is a set of points that don't shoot off to infinity, and it's called a strange attractor if the attractor is itself a fractal.

Stochastic systems, by contrast, are driven by random fluctuations - their dynamics are random in nature, how they 'realise themselves' is random, rather than consisting of specific, determinate mappings. I don't know much about their attractors etc, but there's a similar canonical example in Brownian motion.

A really simple stochastic system to visualise is balancing a small perfectly symmetrical infinitely thin piece of paper on the head of an infinitely thin pin. The motion of the air particles around it causes it to topple in some random direction. IE, the force which drives the dynamics, mapping state to the next state, evolves as a random variable. From what little experience I have with stochastic systems (their differential equations) I can say this: there be fucking dragons. -

Bug with bold italics underline and strikethrough

@Sam26 found it in one of his posts. I pissed about with it for a while and replicated/generalised it.

Thanks to Sam26 for clocking it. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

Take your time.

I'd go further and say 'knowing that X' is a mostly artificial construction, it's a philosophical after-image. To me knowing that seems equivalent to retrojecting a set of competences, beliefs and evaluations which are summarised by 'X knows that P'. It may still be true that {"X knows that P" is true iff X knows that P}, but what knowing that consists of depends on what is known that.

EG: I know that my fridge doesn't have milk in it; why? I didn't buy milk and fridges don't fill themselves. In giving an account for why I know that P, I've supplanted a few reasons that fit in with some contextual cues and an exercise in imagining how I would/could be wrong (then framing that I couldn't through some implicit 'ad absurdum' in 'fridges don't fill themselves').

I think propositional content itself (the right hand side of "X knows that P" is true iff X knows that P) is also formed by some kind of retrojection. This is encoded in the triviality that X knows that P when and only when X can say in truth X knows that P. An exercise in conjuring a proposition to have an attitude towards.

You can contrast this with knowing how, in which an individual has to be able to do the thing not just be able to say truthfully that they can do the thing. This makes me suspicious; where was the proposition in my actions before it was a target for knowing that? I've never found one out in the wild. -

Healthy SkepticismWhat's known has a funny habit of wavering about like a leaf considered under the aspect of eternity. We can bet on the falsity, in the absolute sense, of most things that are known. Something will be wrong with them, they are likely to be flawed in ways we can't even conceive of now, but perhaps they will be less wrong in some ways than their predecessors.

Under the aspect of eternity; what matters is the process that makes that knowledge coalesce into structures. Whether material or ideal, they were enabled by charitable skepticism coupled with courageous belief; embodied in the search for and application of knowledge; and retained by those willing to learn and to teach. All the rest is hard work. -

Drops of GratitudeI expressed gratitude to some posters for their company over the years and their efforts in educating me; I missed a few I'd like to draw special attention to but forgot at the time:

@noAxioms,@Andrew M,@andrewk,@jamalrob,@Srap Tasmaner,@Pierre-Normand,@fishfry,@Banno,@'sheps' (miss them),

there are doubtless some people I've forgotten. -

Struggling to understand Russell's work on logic / Question about learning logic

Luckily there are a lot of introductory texts in logic. Logic With Trees is a popular undergraduate one covering propositional and predicate calculus - sequent calculus, semantic tableaux and elementary model theory for both. You'll also probably have to study modal logic at some point in your degree, this is a free introductory reference with a few citations.

More advanced logic classes might have you learn proof/model and category/topos theory, but I never got to those. :) -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

There are differences in 'how do I know what I know?' in philosophical terms and scientific ones. 'is this argument I found in a biology paper valid?' is the kind of thing philosophy could give you insight on, 'is this argument sound?' is the kind of thing you'd need some philosophical chops and biological chops to answer. 'are the premises true?' are likely to be questions of biology alone. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

Clearly philosophical but not scientific - What is the true nature of reality.

Clearly scientific but not philosophical - What is the structure of DNA.

I'm not sure I agree with this. "How does DNA work?" has an influence on "What is the true nature of reality?", ontology in the broadest sense is the study of being - and it would be very surprising if the structure of (domains of) beings had no influence on the broadest metaphysical questions.

At various points in the history of philosophy, philosophers have sought to answer the broadest metaphysical questions in - and their current epigones would hate this formulation - in an intrinsically reductive way.

The highest questions in Plato are answerable only to ratiocination about abstract ideals.

The highest questions in Aristotle are addressed by appealing to an imposition of form on matter and the categorisation of general types of causes which determine how things unfold; to understand a thing is to understand its categorisation into a pre-developed schema.

Kant and those who followed his Copernican Revolution seem unaware of the irony of seeking the general structure of being in the way minds condition and understand their percepts.

In Hegel too, the understanding of things becomes the understanding of things; through the logico-historical necessity of a developmental trajectory of human consciousness towards greater and greater generality, scope and reflexivity.

In all of these approaches, questions about how things are in the broadest sense turn into questions of a single topic; and human intellect has a privileged role in disclosing the necessities and vagaries of this topic.

Levy Bryant characterises this theme thusly:

Through the Copernican Revolution (Kant's intellectual system), philosophy is rescued of the obligation to investigate the world and now becomes a self-reflexive investigation of how the human structures the world and objects. It is in this respect that philosophy becomes a transcendental anthropology and any discussion of the objects of the world becomes, ultimately, an anthropological investigation. For the object and the world are no longer a place where humans happen to dwell, but are rather mirrors of human structuring activity. It is this that Hegel will ultimately attempt to show in The Phenomenology of Spirit with his famous “identity of identity and difference” or “identity of substance and subject”. If Hegel is able to show that the object, which appears to be so transcendent to and alien to the subject, is ultimately the subject, then this is because the object is already a reflection of the sense-bestowing activity of the subject. — Levy Bryant, Larval Subjects

Perhaps we can add subordination of questions to contemplation of forms and subordination of questions to hylomorphic classification to this list of approaches which seek to replace the plurality of questions implicit in 'what is the general structure of things?' with questions in a single topic. That way, we need not study how things are, we just need to fit their behaviour to a pre-developed system of categories.*

But what is lost from this kind of approach is the domain specificity of the questions. For example, life as conceived by an anthropologist differs from life as conceived by a molecular biologist and differs again from an ecologist or a zoologist. A virologist would have different problems and a different conception of life embedded in those problems. We can trace a middle path, avoiding dogmatic metaphysics but seeking the insights into general questions that the studies of entities and their dynamics have. These different conceptions and their attendant entities are an example of philosophical study - what can we say of life? Are there any general features? What are the conceptual apparatuses we can use to disclose and track things about life?

I agree that it is true that every inquiry has some philosophical implications, but I don't agree that that allows us to dissolve the distinctions between philosophy and other inquiries. If too much is indexed to a particular type of inquiry, much is irrevocably lost from methodological issues.

*edit: of course, it the best insights from these reductive philosophical inquiries should be preserved, and they are still worth studying. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

I agree that sharp distinctions between the two are artificial. But, what kind of things are in scientific thinking but not philosophy and vice versa? -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

I imagine your bullet points are method, but your post is methodology. Of course, doing things well should teach someone methodological lessons upon reflection. Can it be codified into a flow-chart? If so - it's a method.

Can describe the steps in doing a standard statistical analysis (hypothesis test on model parameters) of some data in a similar way:

(1) Describe data collection method and problem data is being used to study.

(2) Identify derivable statistics for problem and their distributions.

(3) Aggregate derived statistics into a statistical model appropriate for research question.

(4) Model fitting - instabilities? weirdness? go to (1) .

(5) Model checking - violated assumptions? go to (1)

(6) Fit checking - what purpose is the model to be given?

(7) Impact assessment - what does the model mean for the problem at hand?

(8) Interpretive conclusions? Ambiguities? Quantificational results? Improvements for further study?

(9) Return to (2) until all avoidable violations and weirdness have been removed or accounted for and fit is adequate.

The kind of inquiry that looks at commonalities between your list and my list is methodological. The kind of inquiry that our lists describes is application of a method. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

I don't think you're being difficult!

I think you're treating method as methodology though. Philosophical analysis of how Charles Button came to hypothesise, correctly, that hallucination was more similar to vision than mental imagery is part of philosophy, maybe part of epistemology or philosophy of science. That's methodology.

The method that the philosophy is talking about isn't a philosophical method, though. Will apply it philosophically and see what happens:

(1) Mystics on PF typically have little to no understanding of science.

(2) Mystics on PF typically believe that their viewpoints are supported by science or are truer to science than science is.

(3) It's pretty likely that someone who's saying their viewpoint (on the level of worldview) is scientific or scientifically inspired is glossing over far too many things. (1,2, observed correlations and analogy)

In some sense 'having a scientifically inspired worldview and glossing over most things' is pretty close to 'having a mystical worldview and little understanding of science', and for me it's a behavioural maxim or equivalence principle between certain styles of posting. I doubt that other people will see such a strong analogy between (2) and (3), but nevertheless the difference in scope. I don't think this is a particularly good piece of reasoning, but I think it's very similar in character - analogical and full of maybe-equivocations maybe-insights - to the 8 pointed one I detailed above. If I spent more time fleshing out its constitutive equivocations, it would be in better standing. I'm just hoping you'll see what I mean.

A suggestive idea might be: methodology is closer to philosophy than method. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

Maybe I've misunderstood you. To me, justification of faults of reason is philosophy. Epistemology.

Hm. I think it's worthwhile figuring out what methodological concerns look like in philosophy discussion, and what methodological concerns look like in a science. Maybe that'll be more informative.

The kind of criticisms someone doing philosophy can level at another's writing:

every fallacy ever, insufficient emphasis on what's seen as a key issue, reframing attempts, parodies, sarcasm, every possible counter-argument. Philosophers can even invent new errors in thought and interpret other philosophical ideas in their light - like transcendental illusions in Kant; how can someone do metaphysics when the kind of necessity that links objects of thought doesn't have to resemble the kind of necessity that links the objects thought about (reasons vs causes etc)? Another related idea is reification, where relationships between people masquerade as relationships between things; like seeing the relationship with a clerk at a kiosk as one of money transfer despite there being a lot more social texture to it. This isn't an exhaustive list.

Philosophers almost have a blank slate to write others' sins on and beat them over the head with.

Experimental science is a little more constrained. Studies can be criticised for confounding, inappropriate sample size or statistical power for the expected effect size, unsatisfied assumptions for any stage of the analysis, poor construct validity (not measuring what you think you're measuring). Imprecise measurements, shoddy error analysis. The general theory behind an experiment can be subjected to a philosophical analysis, but the experimental component of science needs different critical tools. This isn't an exhaustive list.

I think there are also moves a thinker can make in science which are philosophically spurious. Will given an example.

A neuroscientist, Charles Bonnet noticed that people with ocular/retinal or neural pathologies related to vision had a propensity to hallucinate. The hallucinations were purely visual, no other senses were involved. People who had the hallucinations described them as involuntary and occurring seemingly at random, but were more likely to occur when their sufferer was stressed or tired in the evening. From that they were involuntary, Bonnet hypothesised that the hallucinations have more in common with vision alone than with mental visualisation. This was later shown to be the case (somewhat), as hallucinating people with visual pathway damage had neural correlates shown in an FMRI scan which were more similar to people doing ocular tasks than those envisioning objects 'in the head'.

What justifications could Bonnet have ultimately given for his leap of insight? Was there anything logically sufficient from observing the reports of hallucination prone people with ocular damage to force the conclusion that hallucinations are more similar to vision itself than envisioning upon any rational mind? I doubt it, what inspired Bonnet to adopt his conclusion was the disanalogy between envisioning and vision. Specifically, the property of involuntariness that hallucinations and vision share.

The classificatory decision Bonnet made could be represented post-hoc through some formal logical operations, but the thing is Bonnet's decision would have occurred without this translation exercise. Reasoning through loose disanalogies to a generalisation and classification of something is something that's justified for Bonnet but would make for poor philosophical argumentation.

EG the patchwork of his beliefs probably looked something like this:

(1)Bonnet observes reports that people with visual pathway damage hallucinate.

(2)These hallucinations seem and are reported as involuntary.

(3)Envisioning tasks are usually voluntary.

(4)The hallucinations are not a mechanical part of envisioning tasks. (2,3, disanalogy)

(5)The hallucinations are not voluntary. (2,3,4, treating 3 as 'always' rather than 'usually')

(6)Vision can be partitioned into acts of seeing and acts of envisioning.

(7)The hallucinations are seen. (disanalogy with envisioning, 6)

(8)Hallucinations are seen in the same way as ordinary vision. (analogy from 2, 7)

This isn't a logically valid argument, and importantly the moves between steps in the argument aren't done through formal logical entailment - they follow in a rough and ready way characteristic of empirical reasoning of any sort. I think it's more likely that Bonnet had a 'cloud' of concepts similar to those represented in the above list, and that cloud suggested taking the action to hypothesise (8). What would be a fault of reason in philosophy was used scientifically to draw a sensible conclusion. -

My philosophical pet peeves

People who say "x fallacy" in response to something you said without explaining why it's 'x fallacy' is annoying.

I think my biggest pet peeve is responding to the letter of someone's argument rather than its spirit. -

A Wittgenstein Commentary

The interesting part for me, especially about Lewis Carrol's Jabberwocky, isn't that it touches something purely subjective or inner, it's how reliably the poem produces images in people despite being some limiting case of use or indeed sense.

Words like 'slithy', 'gyre', 'frumious' 'manxome' are easily understood, words like 'brillig', not so much. The words in the first list sound like their meaning in some sense, like this, brillig is more abstract and denotes a time of day (according to Humpty Dumpty) - people I've spoken about the poem with usually have 'brillig' connoting something like a frigid, frosty but clear starry night.

Non-native English speakers usually have difficulty with slithy, gyre, frumious and manxome. Native speakers understand 'slithy' as 'slimy/lithe', 'gyre' as somewhere between 'gyrate' and 'flutter', 'frumious' as derived from 'furious' and 'fuming' and manxome as close to manly/tough (with tough being seen as close to 'difficult'). -

A Wittgenstein CommentaryWhat do the resident Wittgenstein apologists make of Lewis Carrol?

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe. -

The Logic of Space and Numbers

That part was more about adding structure to the abductive reasoning in hypothesis formation than it was about designing the actual experiment, but I've never actually done any real research so I probably have no idea what I'm talking about. What do you mean when you refer to much more effort?

As in, more thinking time is spent:

(1) Designing experiments that benefit from orthogonality and have block structures which act as controls for various possible effects.

and

(2) Figuring out a good operationalisation of a concept.

than

(3) Reasoning probabilistically about concepts.

This is because: most of the time the ways you can analyse the data are fixed/induced by the experimental design and how variables are operationalised.

Will give a few examples. If you can take repeat measurements from a single person (or thing) to test something, typically you do that because it provides more precise and less confounded estimates of a treatment's main effect. EG: If you're trying to measure how hard a mental ask is to do, the difference between their pupil diameter during the task and their average pupil diameter before it is a good measurement. That kind of thing could only be observed from experimental practice, and whether it's right or wrong depends on the real world and the experimental set up more than the truth of some theory of cognitive load.

Another example is from Freakonomics, people looking at the average donation per donut to take from a basket of donuts in work-places with different median income. The 'abductive leap' in this case is the claim that this is a measure of generosity of people in white/blue collar jobs.

It's also quite common now for people to skip much of the theorising and measuring stages now, and instead to let a computer do most of your thinking for you. The 'abductive leap' when you're using machine learning algorithms are smaller parts of the study than the operationalisation of variables - for example, you choose the set of kernels for a convolutional neural network analysis, then the data 'fits itself', as it were.

Wouldn't that question asking and answering behaviour be required for the first few steps of the scientific method? How are you defining philosophy and science?

I don't know if I could offer a good definition of philosophy or of science. Regardless, there are a lot of differences between the two. The use of probability theory to evaluate hypotheses - not just in the due course of experimental analysis and design - is at best an idealisation of what scientists do. No one thinks in accordance with the Kolmogorov axioms. -

The Logic of Space and NumbersIf it helps, I've worked in a few scientific research projects and am a statistician, and not once have I been asked to used Kolmogorov's axioms in a Carnap-ian quest for scientific objectivity. Much more effort is placed on designing appropriate controls and resource efficient experimental designs than anything which resembles 'applied probabilistic reasoning' in the sense you outlined it.

If the experiment confirms your hypothesis you will develop an axiom based on observations that the rest of the system will rely on, which can be expanded if the domain of the formal system needs to be expanded. Another option, if one desires to add another level of rigor, is to test other hypotheses as well, in order to satisfy the principle of strong inference. If it doesn’t confirm the hypothesis, go back to the observations and pick the next most probable answer and repeat the process... Scientific inquiry necessary when you have enough time to conduct it and it is important that you are right the first time.

You very rarely 'get it right first time', experimental effects are often subtle, and strong signals from small data-sets are very often noise.

With regard to 'infinite regress' however, Agrippa's trilemma is always going to highlight faulty reasoning in an architectonic system in some way. But some 'faults of reason' are justified in a way that makes inquiry using those faults of reason irreducible to philosophical reasoning. Science bottoms out in the real world - it deals with real abstractions - in a way metaphysics and epistemology usually don't. For example, metaphysical and epistemic concepts are rarely parametrised or operationalised; they don't need to interface with reality in the same way as scientific thoughts do. Another contrastive case - what would an epistemologist specialising in Gettier do with a survey on people's responses to Gettier Cases?

In my view, good philosophy isn't there to vouchsafe the operations of scientific thought, or to ape scientific thinking in a philosophical register - scientific thinking will continue to happen without philosophy's help. Philosophy at its best is a problematiser, a composite of overlapping and sometimes contrary metaphysical, epistemic, ethical and political intuitions which allow it to ask interesting questions. -

Ontological Implications of Relativity

General relativity does not have a

fully developed metaphysics of causation such as would be expected by a philosopher interested in the nature of causation. Rather we should understand the causal structure of a spacetime in general relativity as laying out necessary conditions that must be satisfied by two events if they are to stand in some sort of causal relation. Just what that relation might be in all its detail can be filled in by your favorite account of causation

From the paper you linked. This kind of reasoning is what I've been trying to use all thread. How do the relativities constrain ontologies of space/time/motion?

There is no such thing as the perspective of a photon. The perspective of a photon would be in its "own" reference frame, i.e. a reference frame where the photon is at rest. But there is no such reference frame.

Space-like separation is still a problem for causality. This is why I've (and seemingly the first paper you linked) tried to frame light-cones as a partition between causally connected and disconnected components. Interestingly the paper goes on to say that while this causal account appears necessary, it isn't sufficient once you switch to general relativity - in the sense that this causal connection/partition can be generated by more than one spacetime geometry.

I've not read much of the second paper yet, but there's nondeterminism even in Newtonian mechanics. Nomologically possible indeterminism anyway. -

Ontological Implications of Relativity

This sense of temporal perspectivality is quite independent from whatever the special theory of relativity has to say about time, empirically, except for the manner in which it defines the three regions of the agent-centered light-cone at each instant: limiting possible intervention, or unintended causal influence, to the events located within the "future" region of the light-cone.

On the other hand is the assertion that humans experience of duration is unique in experiencing not physical processes like clocks or anything else physical, but of the advancement of this "ontologically real" present. This would elevate it to an empirical claim, and despite being untested, would seem to be complete nonsense.

In the transition between phenomenological space/time and physical space/time, I think it's quite common - and this is in broad strokes - to make one a derivative of the other. Kant's view on space is a phenomenological one:

Space is not an empirical concept which has been derived from outer experiences. For in order that certain sensations be referred to something outside me (that is, to something in another region of space from that in which I find myself), and similarly in order that I may be able to represent them as outside and alongside one another, and accordingly as not only different but as in different places, the representation of space must already underlie them. Therefore, the representation of space cannot be obtained through experience from the relations of outer appearance; this outer experience is itself possible at all only through that representation. — Kant, CoPR, Transcendental Aesthetic

and time is, again very roughly speaking, an a-priori structure which gives us our index of consecutiveness of experiences.

In the same regard, Heidegger's view of space - however different in character - makes physical space (and time) derivatives of various existentialia (roughly, 'fundamental properties of experience')

For example, an entity is ‘near by’ if it is readily available for some such activity, and ‘far away’ if it is not, whatever physical distances may be involved. Given the Dasein-world relationship highlighted above, the implication (drawn explicitly by Heidegger, see Being and Time 22: 136) is that the spatiality distinctive of equipmental entities, and thus of the world, is not equivalent to physical, Cartesian space. Equipmental space is a matter of pragmatically determined regions of functional places, defined by Dasein-centred totalities of involvements (e.g., an office with places for the computers, the photocopier, and so on—places that are defined by the way in which they make these equipmental entities available in the right sort of way for skilled activity). For Heidegger, physical, Cartesian space is possible as something meaningful for Dasein only because Dasein has de-severance as one of its existential characteristics. — SEP, Martin Heidegger, Spatiality

De-severance functions as a spatialising structure in which relevant objects for my activity are 'nearby for me' and irrelevant objects are 'distant from me'. Heidegger argues at length that the Cartesian conception of space - still present in special and general relativity, they are modern forms of Cartesian coordinate systems; real valued vector spaces - as a field of orthogonal extensions, and my place in it as a point, is derivative from this more primordial spatiality of my experience.

Time, also, is treated as derivative of the orientation of experience. Orientation, again roughly, has the component of futurity - my plans, what I will do next; the component of the present - my engagement with what I'm doing; and the component of the past - what needed to happen to be doing what I'm doing now. It should be noted that these elements work by structuring how I'm doing what I'm doing, and 'the experiential moment' is dispersed and elongated with respect to the futural,present and past aspects of Heidegger's phenomenological time. If you want to read more on this, the terms are 'fallenness', 'thrownness' and 'projection'.

Obversely, it is possible to imagine human experiential time and space as derivatives of physical time and space. The Circadian rhythm being coupled to the sun and the differences between neurotransmitter activity in the brain, the sense of fatigue from mental and physical exertions giving some sort of inner clock coupled with the one we obtain from day and night (or more generally light level). We could say that experiential time is an illusion projected from the the non-relativistic speed of our day to day activities.

I'd like to say at this point that I don't think either of these approaches gives much respect to the particularities of the derivative space/time concept. Accounts of phenomenological space/time are good at describing phenomenological time, science of physical space/time is good at describing physical space/time.

I think the following is a worthwhile question:

In what senses is our phenomenological space/time related to physical space/time? Deriving one from the other has a few problems:

(experiential allows derivation of physical) -> vulnerability to arche-fossils

(physical allows derivation of experiential) -> hard to give an account of differences between the two. (eg, flow-states and time perception)

The discussion so far as highlighted three connected ideas which act as a conceptual bridge between physical space/time and experiential space/time, namely:

(1) Time-like separation between events in Earthly reference frames is prerequisite for maintaining the order of cause and effect. This is a bit of an imprecise formulation but I think it suggests the right idea. Stuff has to be moving slowly, stuff has to be close on a cosmic scale, in order for us to get the real properties we have out of physical time accounts which use relativity.

(2) Light-cones as partitions between causally connected components of space-time.

(3) Limiting theorems of SR and GR reduce their dynamics to typical Earthly ones for most processes, so SR and GR can be incorporated in an ontology of space time.

Ever since I read a reasonable amount of Heidegger, and then Meillassoux' criticism of (experiential->physical) time derivations, I've thought it would be an interesting question to ask:

How do humans internalise physical space and time? How do experiential space/time allow us to act in a universe with a space/time alien to our own? An operational question, rather than casting one space/time as logically prior to another. -

Should Persons With Mental Disabilities Be Allowed to Vote

Maybe political scientists and psychometricians presently better heed the warnings and caveats from the professional statisticians who devise their methods and the software packages that they use

This is a bit off topic, but I think it's of general interest.

The methodological flaws that lead to the replication crises are still operative. Some of this can be attributed to 'publish or perish' culture, but I think - and I have little evidence for this compared to the enormity of the claim - that the interaction of:

(1) poor applied statistical pedagogy,

(2) low standards for experimental design

(3) 'convenience sampling' being equated to genuine random sampling strategies

(4) the identification of performing hypothesis tests with enacting an empirical paradigm of research.

(5) the identification of scientific relevance with a rejected null hypothesis

is a driving force of poor quality science.

Hypothesis tests themselves reward noisy data collection. Gelman and his coauthors have worked extensively on this recently. And in 2014 a biomedical science journal outlawed the use of p-value hypothesis testing in submitted papers. Hopefully the times they are a'changing. -

Should Persons With Mental Disabilities Be Allowed to Vote

If this makes you feel any better, when we (statistics students) were taught confirmatory factor analysis at university, we were strongly advised never to perform it for ethical reasons (see 'non-uniqueness of factor loadings' here), especially to avoid varimax rotation. Instead it was strongly implied that we use principal components in exploratory factor analysis instead. To my knowledge p-hacking is also cautioned against now, but the replication crisis wasn't yet a fashionable topic to teach budding statisticians.

Edit: The rule of thumb is: quantities derived from observational studies have indeterminate causal structure. The most you can do is rule some structures out. Further, thou shalt not interpret small studies causally without systematic controls and power calculations. He who does not do statistical power calculations (or type M&S error simulations) has forgotten the face of his father.

fdrake

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2025 The Philosophy Forum