Comments

-

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonThe law of identity, "a thing is the same as itself" indicates that there is an identity ("correct construal" if you like), which inheres within the the thing itself, therefore independent of interpretation. — Metaphysician Undercover

In classical philosophy—especially in Platonic and scholastic traditions—particulars are not intelligible in and of themselves, but only insofar as they participate in or receive a form or essence. Their identity is not something they generate, but something they manifest - in the theistic traditions, bestowed by the Creator.

This contrasts with modern metaphysical assumptions, which often treat particulars as having an independent reality. Eckhart: “creatures are mere nothings”. From within this perspective, the mind doesn’t impose identity, but recognizes it through a kind of intellectual illumination that reveals a deeper metaphysical order (by recognising the form or what-it-is-ness of the particular being.) -

The FormsIt’s tempting to draw parallels between Plato’s Forms and modern physics—especially when figures like Heisenberg make explicit reference to Platonic ideas. But we should be cautious about pressing these analogies too far. The concept of Forms in Plato is not about invisible particles or mathematical abstractions per se, but about the intellect’s ability to grasp stable, intelligible principles that underlie the flux of experience.

This ability—what Plato would associate with the logistikon, the rational part of the soul—is foundational to reason itself. The Forms are not hypotheses about what “really exists” in some otherworldly sense, but expressions of the truth that the rational mind is oriented toward what truly is, not just to appearances. We can only recognize something as a tree, as just, as a triangle, because our minds can apprehend something universal, not merely register a bundle of sensations.

This whole conception of reason—as the faculty that “sees” the intelligible—is central to classical philosophy but has largely fallen out of favor in modern thought, due in no small part to the cultural and intellectual impact of empiricism. When knowledge is reduced to sensation and association, the idea that the mind participates in intelligible being comes to seem obscure or mystical - even if we're actually doing it every moment! And then when attention is drawn to that, we can't see it for looking.

But perhaps the real insight in Plato—and what Heisenberg may have been reaching for—is that the intelligibility of nature is not something we impose on the world, but something we discover because of the rational capacity to see what is. That’s a metaphysical claim, not a physical one, but it's crucial to any deeper understanding of what Plato's forms are supposed to mean.

Oh - and welcome to the Forum. :clap: -

Israel killing civilians in Gaza and the West BankI haven't been following this thread too closely, but like everyone, am appalled by the bloodshed and suffering of the Palestinians we see on news bulletins every day. This morning, there was a report that Hamas had agreed to release 10 more hostages in return for a 70-day ceasefire - quickly denied by Israel and the US negotiator Witkoff.

So the question I have is, why isn't Hamas releasing the remaining live hostages, and returning the remains of the others? What advantage do they hold by retaining them in captivity? If they were to release them, wouldn't that pressure Israel to relent? -

Positivism in PhilosophyAre things (e.g. cats, trees, clouds, etc.) "in the senses" or are they "projected onto the senses," or "downstream abstractions?" Empiricism has tended to deny the quiddity of things as "unobservable," but a critic might reply that nothing seems more observable than that when one walks through a forest they sees trees and squirrels and not patches of sense data. Indeed, experiencing "patches of sense data without quiddity," — Count Timothy von Icarus

All due respect, I think you’re complicating the picture a little. John Locke, who was the emblematic British empiricist, was of the view that the mind is a blank slate, tabula rasa, on which impressions are made by objects. The term ‘quiddity’ is from scholastic philosophy, is precisely the kind of thing that Locke wouldn’t appeal to. He is associated with representative realism, whereby images represent objects, and general ideas are abstracted from the perception of many similar objects. J S Mill took a similar view.

RevealI’ve quoted this many times before, Jacques Maritain’s criticism of empiricism in The Cultural Impact of Empiricism:

For empiricism there is no essential difference between the intellect and the senses. The fact which obliges a correct theory of knowledge to recognize this essential difference is simply disregarded. What fact? The fact that the human intellect grasps, first in a most indeterminate manner, then more and more distinctly, certain sets of intelligible features -- that is, natures, say, the human nature -- which exist in the real as identical with individuals, with Peter or John for instance, but which are universal in the mind and presented to it as universal objects, positively one (within the mind) and common to an infinity of singular things (in the real).

Thanks to the association of particular images and recollections, a dog reacts in a similar manner to the similar particular impressions his eyes or his nose receive from this thing we call a piece of sugar or this thing we call an intruder; he does not know what is sugar or what is intruder. He plays, he lives in his affective and motor functions, or rather he is put into motion by the similarities which exist between things of the same kind; he does not see the similarity, the common features as such. What is lacking is the flash of intelligibility; he has no ear for the intelligible meaning. He has not the idea or the concept of the thing he knows, that is, from which he receives sensory impressions; his knowledge remains immersed in the subjectivity of his own feelings -- only in man, with the universal idea, does knowledge achieve objectivity. And his field of knowledge is strictly limited: only the universal idea sets free -- in man -- the potential infinity of knowledge.

Such are the basic facts which Empiricism ignores, and in the disregard of which it undertakes to philosophize. The logical implications are: first, a nominalistic theory of ideas, destructive of what ideas are in reality; and second, a sensualist notion of intelligence, destructive of the essential activity of intelligence. In the Empiricist view, intelligence does not see, for only the object or content seen in knowledge is the sense object. In the Empiricist view, intelligence does not see in its ideative function -- there are not, drawn form the senses through the activity of the intellect itself, supra-singular or supra-sensual, universal intelligible natures seen by the intellect in and through the concepts it engenders by illuminating images. Intelligence does not see in its function of judgment -- there are not intuitively grasped, universal intelligible principles (say, the principle of identity, or the principle of causality) in which the necessary connection between two concepts is immediately seen by the intellect. Intelligence does not see in its reasoning function -- there is in the reasoning no transfer of light or intuition, no essentially supra-sensual logical operation which causes the intellect to see the truth of the conclusion by virtue of what is seen in the premises. Everything boils down, in the operations, or rather in the passive mechanisms of intelligence, to a blind concatenation, sorting and refinement of the images, associated representations, habit-produced expectations which are at play in sense-knowledge, under the guidance of affective or practical values and interests. No wonder that in the Empiricist vocabulary, such words as 'evidence', 'the human understanding', 'the human mind', 'reason', 'thought', 'truth', etc., which one cannot help using, have reached a state of meaningless vagueness and confusion that makes philosophers use them as if by virtue of some unphilosophical concession to the common human language, and with a hidden feeling of guilt. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Trump says Putin ‘has gone absolutely CRAZY!’ “Missiles and drones are being shot into Cities in Ukraine, for no reason whatsoever,” Trump says.

So DJT seems suddenly to have become aware of the fact that Putin is groundlessly and indiscriminately firing missiles and drones and killing Ukrainian citizens - three years after the invasion started. I would say 'better late than never', but you don't know what he's going to say next. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?But the point at issue is, whether time is real independently of any scale or perspective. So a 'mountains' measurement of time will be vastly different from the 'human' measurement of time.

Sensory information doesn't really come into it. Clearly we have different cognitive systems to other animals, but the question of the nature of time is not amenable to sensory perception.

Anyway - I can see we're going around in circles at this point, so I will leave it at that. Thanks for your comments. -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonStill don't see any justification for the claim that the Earth could have only one moon as 'a matter of natural law'.

You'd have to assume random things happen for no reason, contrary to the PSR. — Relativist

Just remind me again why Einstein said he doesn't believe that God plays dice? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?I am nit sure what the thought experiment conveys. — Apustimelogist

You said, 'So if something is mind-dependent, it co-varies with the state of your subjective state of mind.' The 'mountain' thought experiment shows how one's sense of reality is dependent on the kind of mind. Hence, mind-dependent.

The image needs to be put on a media, but the media doesn't change the image, or it is not necesdarily the case that it does, it seems to me. — Apustimelogist

Right - one of the points that I often make, which is the symbolic or representational or semantic level is separable from the physical. -

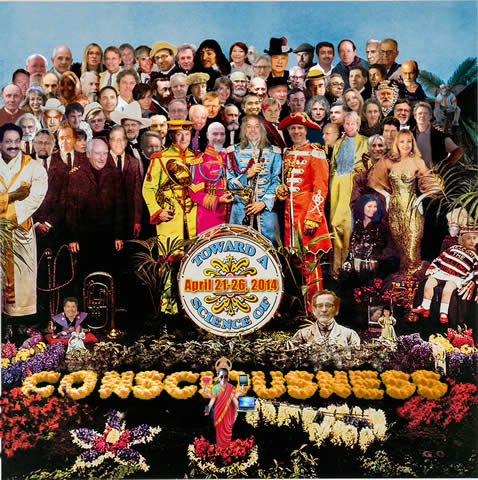

Positivism in PhilosophyWell, the times surely are a'changing. Something a lot of people don't appreciate, is that around the time David Chalmer's published his famous Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, he was a a keynote speaker at the initial Science of Consciousness conference in Arizona (convened by Stuart Hameroff.) The TSC conferences are widely regarded as a landmark event, bringing together scientists and philosophers from various disciplines to discuss consciousness in a serious academic setting. This undoubtedly contributed to big changes in the field.

Herewith the image from the 2014 (20th Anniversary) conference, with everyone in the picture being some philosopher of mind or consciousness.

Deepak Chopra cheek-in-jowl with Daniel Dennett. Who'd have thought? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Dependence means that things co-vary. So if something is mind-dependent, it co-varies with the state of your subjective state of mind (withstanding you representing or seeing it). — Apustimelogist

It depends on mind in a different way to that. A thought-experiment I have posed is: imagine that mountains were consciously aware. A mountain has a life-span of hundreds of millions of years. To a mountain, human beings would be imperceptible, because their life spans are so minute as to be incomprehensible. You wouldn't be aware of a Mallory or a Hillary. Glaciers, you might recognise, as they'd be around long enough to register and carve canyons in your flanks. At the other end of the scale, imagine an intelligent microbe. Its entire lifespan of one human hour might be spent inside the internal organs of a larger creature. Again, it would have no conception of the scale or time-span that constitute that creature's life (like the flea who says 'I don't think I believe there's a dog' :razz: )

As for the photograph, it represents something to you because you know what a likeness is, you know what it means, and what it has captured, and that it is representative. But physically, it is not the reality it represents, it is plastics and polymers. The ability to reproduce the image depends on the technology of inkjet printers but the interpretation is dependent on your mind.

I get how difficult this is. I think this passage from Bryan Magee captures the difficulty many of us have in grasping what’s at stake in transcendental idealism. It helps explain why the view seems so implausible at first—but also why it deserves patient attention:

This, incidentally, illustrates a difficulty in the way of understanding which transcendental idealism has permanently to contend with: the assumptions of 'the inborn realism which arises from the original disposition of the intellect' enter unawares into the way in which the statements of transcendental idealism are understood, so that these statements appear faulty in ways in which, properly understood, they are not. Such realistic assumptions so pervade our normal use of concepts that the claims of transcendental idealism disclose their own non-absurdity only after difficult consideration, whereas criticisms of them at first appear cogent which on examination are seen to rest on confusion. We have to raise almost impossibly deep levels of presupposition in our own thinking and imagination to the level of self-consciousness before we are able to achieve a critical awareness of all our realistic assumptions, and thus achieve an understanding of transcendental idealism which is untainted by them. This, of course, is one of the explanations for the almost unfathomably deep counterintuitiveness of transcendental idealism, and also for the general notion of 'depth' with which people associate Kantian and post-Kantian philosophy. Something akin to it is the reason for much of the prolonged, self-disciplined meditation involved in a number of Eastern religious practices. — Bryan Magee, Schopenhauer's Philosophy, p106 -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonOk not ‘seem’. ‘Are’.

-

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonSure—but I think we have to distinguish between how laws are discovered (epistemology) and what they describe about the world (ontology). You're right that laws like Newton's were formulated after observing motion, and that our models change with better observations. But that doesn't necessarily mean motion itself is lawless or "undetermined" in some deeper sense.

In the Newtonian framework—within its applicable range—the laws don't just describe motion, they enable precise prediction. If I know the mass, velocity, and position of a satellite, and I apply Newton’s equations, I can calculate where it will be tomorrow, and I’ll be right (at least to an excellent approximation). That’s more than just post hoc description—it reflects an underlying law-like regularity.

Granted, this breaks down at relativistic scales or in quantum domains—but that’s part of the point. Lawfulness can be domain-specific, and even in more advanced physics, the idea of constraint or structure doesn't vanish. It just becomes subtler. So I’d still say there’s a real sense in which orbital motion is determined—at least within the scope of classical mechanics.

So: yes, our formulations of the laws are historically contingent and always open to revision. But the regularities they describe are not arbitrary. They're what allow us to build spacecraft that actually arrive at their destinations. The laws of motion can predict how moons orbit planets, once they exist—but those same laws don’t determine how many moons a given planet will have. That depends on many contingent factors—collisions, accretion history, nearby bodies, etc.—that fall outside the scope of deterministic prediction. There’s lawfulness in how systems behave, but not everything that happens is fixed by those laws alone.

I think the interesting philosophical point is precisely the sense in which the laws of nature seem true a priori, irrespective of experience. I mean, whenever something is suggested that might not obey those laws on this forum, merry hell usually follows :-) -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonWe're assuming QM is deterministic). You'd have to assume random things happen for no reason, contrary to the PSR. — Relativist

But I think that's a huge assumption. Even if it were true the amount of information one would have to have to calculate how many satellites a given planet could have is unknowable in practice, and it is known there are planets with more than one satellite (even other planets in our solar system.) The OP frames the relationship between PSR and determinism as binary—either every event is strictly determined, or not. But the relationship isn’t that simple. The principle of sufficient reason claims that everything has a reason or sufficient condition. However, that reason doesn't necessarily dictate a single, fixed outcome in all cases, it might only provide a range of possibilities (which is exactly what the Schrodinger equation does, come to think of it.) Meaning there can be degrees of likelihood, within a range (like, the particle will be registered, but it won't be a watermelon.)

And furthermore, natural laws are based on idealisations and abstractions - point particles, frictionless planes, and so on - which we don't encounter in reality. So in short, I don't see an a priori reason why a planet such as ours doesn't have two moons - it is a contigent fact. -

How do we recognize a memory?Our new Dear Leader is planning a YUGE military parade on his upcoming birthday, the largest for more than 40 years. — J

I wonder if he'll have the massed missile launchers and tanks, like his comrade, Putin.

ON the OP, the only thing I have to add, is that when an aged relative was in her dotage and suffering dementia, one of the things I noticed is that she lost all sense of when memories had occurred. She would refer to people or events that we knew had happened decades previously as though they had just happened. ('Where is Lynne? She said she would call' - Lynne having died decades previously.) The metaphor I thought of was the index on a hard drive being corrupted so that random pieces of memory were floating to the surface of her conscious awareness without any reference to her current experience (which was, of course, very sad to see, although she did not appeared distressed by it.)

The other general point I've noticed in my own life is the deceptiveness of memory. One can have an apparently crystal-clear recollection of an episode or a scene in your life from years previously (now I'm older I notice this) but then find out that you weren't in that place at that time, or some other aspect of the memory is fictitious. -

Demonstrating Intelligent Design from the Principle of Sufficient ReasonNo, because the single moon is present as a result of the deterministic laws of nature. — Relativist

Sorry to but in, but surely the number of moons a planet has, and the number of planets a solar system have, is not determined by any laws of nature. What is determined is how they orbit their stars and planets. What could not occur would be an orbital path not determined by those laws. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?The title of this thread—“Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?”—is precisely the issue. You seem to be assuming that we’ve already answered that question in the affirmative by default, and that everything else is just subjective garnish (“schm-ime”). But the whole point of this discussion is to ask: what do we mean by the “reality” that is supposedly 'mind-independent', and does it make sense without reference to a subject? That’s not a scientific question—it’s a philosophical one. I think there's a real distinction to be made.

I trivially need experiences to experience that fruit that is beared, but if humans can construct models and ways to examine those models and their empirical consequences in ways that are not changed by subjective experiences (in virtue of experiential subjectivity), then in what sense do they depend on the subjective. — Apustimelogist

You say you “trivially need experiences to experience the fruit that is beared,” but that’s actually the core issue. It’s not just that we need experience to observe outcomes—experience is the condition for building, interpreting, and validating any model at all.

Scientific models may not change based on individual subjectivity, but their entire framework—measurement, comparison, meaning—depends on the shared structures of cognition. That’s not a scientific claim; it’s a philosophical one. You can’t eliminate the subject without also eliminating the possibility of modeling anything in the first place.

But, if we agree that you do support the idea of a mind-independent reality, then perhaps we can leave it at that. -

The FormsWerner Heisenberg was a lifelong Platonist. He was known for carrying a copy of the Timeaus with him when a student, and wrote intelligently on philosophy and physics. See his The Debate between Plato and Democritus', a transcribed speech, from which:

...the inherent difficulties of the materialist theory of the atom, which had become apparent even in the ancient discussions about smallest particles, have also appeared very clearly in the development of physics during the present century.

This difficulty relates to the question whether the smallest units are ordinary physical objects, whether they exist in the same way as stones or flowers. Here, the development of quantum theory some forty years ago has created a complete change in the situation. The mathematically formulated laws of quantum theory show clearly that our ordinary intuitive concepts cannot be unambiguously applied to the smallest particles. All the words or concepts we use to describe ordinary physical objects, such as position, velocity, color, size, and so on, become indefinite and problematic if we try to use them of elementary particles. I cannot enter here into the details of this problem, which has been discussed so frequently in recent years. But it is important to realize that, while the behavior of the smallest particles cannot be unambiguously described in ordinary language, the language of mathematics is still adequate for a clear-cut account of what is going on.

During the coming years, the high-energy accelerators will bring to light many further interesting details about the behavior of elementary particles. But I am inclined to think that the answer just considered to the old philosophical problems will turn out to be final. If this is so, does this answer confirm the views of Democritus or Plato?

I think that on this point modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are, in fact, not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word; they are forms, structures or — in Plato's sense — Ideas, which can be unambiguously spoken of only in the language of mathematics.

I find the question of whether sub-atomic phenomena exist 'in the same way' that stones and flowers do very interesting. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?I just wanted more clarity on the meaning of space and time as about in the head, not outside it. Clearly, what we perceive is embedded in what is going on in our heads. Clearly we cannot perceive / experience everything, every event in the physical reality outside our heads that makes a difference, that has an effect on other things in reality. But nonetheless, I think what we do experience, or at least a significant amount of it has a broadly consistent mapping to specific things that actually go on. To me, that is enough to say that we see real stuff in a weak sense. I think there is no observable intrinsic fact-of-the-matter about representation, only a dynamic statistical coupling between brains and the world which a scientist or philosopher can cash out as representation. The coupling is enough. If I think of veridicality weakly in terms of a kind of coupling or mapping then there is not really a sense that I could exhaustively couple a system to the rest of reality and have it miss anything about reality. When stuff is missed, it because there are couplings missing that give us novel information. Space and time can also be seen in terms of these kinds of couplings, at least the concepts we have made reasonably precise by measurement (i.e. objective time). My subjective sense of space and especially time may be more fallible or is different for various reasons (e.g. speculatively: because time and space are inferred through informational properties of the brain which can be easily perturbed, e.g. if I close my eyes, I lose some of the information required to specify physical space (at least at some allowable resolution) and become more reliant on say body information than I normally would); if subjective time could plausibly related to information flow (e.g. entropic time by ariel caticha), then information processing in my head may distort my sense of time).

So maybe there are discrepancies between objective time "inside" and "outside" as it were but only in some sense that informative couplings have been missed to some part of reality. Good example is obviously relativity phenomena like time-dilation. Maybe the way brains work or learn over time mean that mappings or couplings can be established or parcelled out in different ways; but nonetheless these are just different mappings to events that actually occur, and they are overlapping or inter-relatable so that even though I may be measuring in inches or centimeters, because they are being mapped to the same stuff in reality, there is no sense that these different perapectives are telling me anything new or different about space. And there is nothing else to know about space beyond my sensory boundaries unless that thing to know about space makes some physical difference (because space is physical) to observations and theories and experiential perceptions. — Apustimelogist

Thanks for that, I only just noticed it now, for some reason it wasn't picked up in Mentions.

I think your analysis illustrates the problem Bergson was concerned about. When you say that space and time can be understood as “informative couplings” or as co-ordinate systems tracking changes, you’re describing what clocks and instruments do—they measure intervals between states. That’s fine for physics. But the philosophical point is that this doesn’t capture what time is, as in some fundamental way, it is lived. That is the sense in which it is still observer dependent.

Let me again paste in the passage from the Bergson-Einstein debate which I think is the relevant point:

At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. This is why Bergson believed that clock time presupposes lived time.

Bergson appreciated that we need the exactitude of clock time for natural science. For example, to measure the path that an object in motion follows in space over a specific time interval, we need to be able measure time precisely. What he objected to was the surreptitious substitution of clock time for duration in our metaphysics of time. His crucial point in Time and Free Will was that measurement presupposes duration, but duration ultimately eludes measurement.

Bergson’s insight was that clocks don’t measure time; we do. What we call “objective time” (e.g., seconds, hours, spacetime intervals) depends on our ability to synthesize change into a unified experience. The sequence of tick-tock-tick has no meaning unless it is held together in memory and felt as a flow; there is no time for the clock itself. Otherwise, it’s just isolated instants. That sense of flow—duration, which is fundamental to time —cannot be reduced to or captured by measurements alone. As Bergson put it, measurement presupposes duration, but duration eludes measurement.

The point isn’t that subjective time is a distortion of the real thing, but that subjective time is the ground of our sense of temporality itself. What you're calling “couplings” only make sense against the backdrop of a temporally structured awareness. Without someone to whom change occurs as change, your "objective time" is just an uninterpreted sequence of events with no temporal character.

Which, in turn, goes back to the idealist (or constructivist) argument: the subject cannot be subtracted from the equation without also subtracting the very conditions under which space, time, and objects can be said to exist. We can behave as if there is no subjective awareness of time for practical purposes, but this conceals a philosophical sleight of hand—the erasure of the subject whose presence is in fact a precondition for the very intelligibility of space, time, and objectivity.

Where this calls realism into question is not by saying the sensed world is illusory or imaginary, but by showing that the subjective pole of experience can't be eliminated, even though it can be forgotten. And that is very much what Evan Thompson, author of the Bergson-Einstein essay, is concerned with, as he says this 'forgetting' of the subjective ground of science constitutes its 'blind spot'. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?When Wayfarer is presented with arguments that refute his ideas and which he has no answers to he resorts to labelling them as "positivist" in an attempt to discredit and dismiss them. — Janus

I will say that your posts reflect a positivist attitude when they do. I could, if I was bothered, find any number of examples of that in our discussions in years past - science as the arbiter of what is real, the subjectivity of religious or spiritual maxims, which might have poetic or affective value, but convey no truth. And so on. I'm not the least 'intellectually dishonest', I go to great lengths to explain and defend my views. -

Positivism in PhilosophyEverything there is, for the knowing mind, can’t be reduced to the physical/empirical, while that mind is doing the reduction. — Fire Ologist

That same mind which is bracketed out of early modern science with the division of the primary and secondary attributes - primary being those precisely measurable and quantifiable, secondary being color, taste, smell, and those other attributes which rely on subjective apprehension. Within that milieu, physics becomes paradigmatic, because of its precision and its universality. The laws of motion, for example, are thought to be universal in scope (which they are, subject to the limitations later discovered by relativity.)

The upshot of which is that the mind then has to be re-introduced to the world from which it has been banished, as a consequence or result of these same ‘universal’ physical forces which finds its most consistent expression in so called ‘eliminative materialism’. A hard problem, indeed.

Starting from the idea that sciences are universal, there is then often this attempt then to create a mathematical theory of something, something like physics. If it's mathematical, it's scientific! — ssu

Pretty much as I said above. It is, to allude to a rather controversial, but also profound, book, ‘the Reign of Quantity’. One of the discussions that prompted this thread, was about how qualia (an item of academic jargon in philosophy of mind referring to the qualities of subjective experience) can be explained away as illusion.

I also don't have much use final causes. — T Clark

From my readings on it, final causality was a fatal flaw in Aristotelian physics, as it in effect attributes intentionality to inanimate objects (i.e. a stone’s ‘natural place’ is on the Earth.) But it’s very different in biology, where indeed there’s a pretty strong ‘neo-Aristotelian’ revival nowadays. After dispensing with ‘teleology’, biologists found in necessary to re-introduce ‘teleonomy’ referring to the apparent goal-directedness of organisms ( wiki). It’s been said that Aristotle’s biology anticipated the discovery of DNA, not because he had any idea of molecular biology, but because he had worked out what is necessary for the transmission of traits.

Besides final causality is routinely invoked in day-to-day life. ‘Why is the kettle boiling?’ can be answered with either ‘because the water has reached boiling point’ or ‘I want to make tea’. Both are course correct but they answer slightly different questions.

Seems to me your proposing a kind of pragmatic redefinition of positivism, suggesting that its value lies in yielding useful or predictive models. But but that wasn't the central concern of logical positivism, which were epistemic and semantic—concerned with the meaning and justifiability of statements. Popper’s falsifiability criticism was a critique of the verification principle. While pragmatic utility is important in science, it doesn’t rescue the philosophical framework of positivism from its internal and methodological issues. I can see circumstances where a positivist attitude is pragmatically useful. But that isn't the point at issue.

There is a pretty massive conflation common in this area of thought re "science" and "empiricism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

It's not that difficult: empirical data is what can be captured by the senses (or instruments). Basically, what is tangible, physical, 'out there somewhere'.

(It is interesting to ask whether Popper's work remains within or moves beyond Positivism. I suspect that Wayfarer might say that Popper's response is a kind of extension of Positivism.) — Leontiskos

I don't think so. Recall that the initial targets of Popper's critique were psychoanalysis and marxist economics. Both of these were held up as being scientific theories. Popper pointed out that they were so poorly defined that they could accomodate any kind of observation - they couldn't be falsified. He contrasted that with Einstein's theory of relativity, which was subject of empiricial confirmation (or disconfirmation) which came from Eddington's observation of the gravitational deflection of starlight in 1919.

Besides, Popper, later in life, developed his 'third worlds' ontology which I think would be very different from anything the positivsts would endorse. In The Self and Its Brain, co-authored with John Eccles, he explicitly defends a form of interactionist dualism, rejecting the reduction of mind to brain — a clear departure from physicalist or positivist assumptions.

Even though Positivism & Empiricism, postulated as-if universal principles, fail their own test, they still serve as good rules of thumb for Scientific investigations into the material world. — Gnomon

Of course. It's when they're applied to 'the problems of philosophy' that tend towards 'scientism' - as you say. -

Positivism in PhilosophyThanks. In positivism’s heyday, this wasn’t obvious. I did a unit on Language Truth and Logic as an undergrad, that and B F Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity were the two books I loved to hate. (Passed the unit, though.)

i’ve often mentioned that a lecturer I had in philosophy, David Stove - incidentally not the one who gave the LTL course - used to compare positivism to the mythological uroboros, the snake that swallows its own tail. That was based on the closing words of Hume’s Treatise - ‘take any book of scholastic metaphysics….’. Stove pointed out that the same criticism applied to Hume’s text. Hume wrote his Treatise as a critique of previous philosophy, but at the same time, his book was also presented as philosophy. ‘The hardest part’, Stove would say, with a mischievous grin, ‘is the last bite.’

Something I noticed reading the material on Comte was this:

the positive or scientific stage represents the pinnacle of intellectual development, where understanding is based on empirical observation, experimentation, and the discovery of verifiable, scientific laws. In this ultimate stage, humanity abandons the search for absolute causes and instead focuses on observable facts and the relationships between them. — Wayfarer

‘Abandons the search for absolute causes’ is a pregnant phrase. By this, I’m sure Comte was referring to the final causes in scholastic-Aristotelian philosophy, the reason that things exist or happen to be. This rejection of final causation is the beginning of the so-called ‘instrumental reason’ that is characteristic of Enlightenment and post-enlightenment philosophy. I recall an exchange in a televised debate between Richard Dawkins and a Catholic Bishop, who was posing the ‘but why are we here?’ question. Dawkins replied ‘Why we exist, you're playing with the word "why" there. Science is working on the problem of the antecedent factors that lead to our existence. Now, "why" in any further sense than that, why in the sense of purpose is, in my opinion, not a meaningful question.’ Had I been in the audience, I would have stirred the pot by asking ‘why?’ - but I wasn’t and the debate moved on. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Of course not, and that was not why I described your views as positivist. It was more in response to posts such as:

So there is nothing more to say about the metaphysics of reality beyond our best scientific models that supervene on the physical — Apustimelogist

Which meets the description of positivism. (I’ve also posted a separate OP on the subject.) -

The FormsSO, what are your thoughts about the ineffability of mathematics and the problematic translation of Truth rendered in mathematics, which is poorly understood as a language that can be seen in informal languages? — Shawn

I think the intuition that animated the Greeks was that mathematical reasoning (Dianoia) provided an insight into a higher level of reality than did sensory perception. Even though it may be true that understanding advanced mathematics is a difficult task (one I’ve never mastered), it’s not that difficult to understand this intuition. After all, numbers never come into or go out of existence, they are not subject to change and decay as are the objects of sense, so surely, the argument has it, they are nearer the source of truth than the opinions we have about the material world. And if you consider the role that mathematics has played in science I think this basic intuition has been amply validated.

The reason that it is at odds with much of what modern philosophers think is because of the cultural impact of empiricism, which, recall, emphasises sense-experience as fundamental:

Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

Platonism, as mathematician Brian Davies has put it, “has more in common with mystical religions than it does with modern science.” The fear is that if mathematicians give Plato an inch, he’ll take a mile. If the truth of mathematical statements can be confirmed just by thinking about them, then why not ethical problems, or even religious questions? Why bother with empiricism at all?

And from another source:

Mathematical objects are in many ways unlike ordinary physical objects such as trees and cars. We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses. It is not obvious that we learn about mathematical objects this way. Indeed, it is difficult to see how we could use our senses to learn about mathematical objects.

So does the distrust of Platonism really come down to the fact that Plato's 'ideas' are not things that exist in space and time, and that the only reality they could possess are conceptual? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?So touching to see the camaradie amongst the forum positivists.

-

What is Time?It is beyond my comprehension that in a Universe 93 billion light years across that has existed for around 13 billion years, the determinacy of the path of photons throughout this Universe is dependent on a few scientists making measurements on the 3rd rock from the Sun. — RussellA

The problem is with taking scientific realism at face value. I watched Sabine’s presentation on T’Hooft. Likewise Roger Penrose and Albert Einstein said they thought quantum physics is radically incomplete. And they too were scientific realists. Penrose says in an interview:

It (quantum mechanics) doesn’t make any sense, and there is a simple reason. You see, the mathematics of quantum mechanics has two parts to it. One is the evolution of a quantum system, which is described extremely precisely and accurately by the Schrödinger equation. That equation tells you this: If you know what the state of the system is now, you can calculate what it will be doing 10 minutes from now. However, there is the second part of quantum mechanics — the thing that happens when you want to make a measurement. Instead of getting a single answer, you use the equation to work out the probabilities of certain outcomes. The results don’t say, “This is what the world is doing.” Instead, they just describe the probability of its doing any one thing. The equation should describe the world in a completely deterministic way, but it doesn’t — Sir Roger Penrose, Interview, Discovery Magazine

The question is, why should it? What if reality is not completely determined by physical principles? -

What is Time?Why should it be that because a photon's path through space and time is unknowable to an observer, that its path is not spatially and temporally objectively deterministic?

A photon of light leaves the Andromeda Galaxy and enters a person's eye 2.537 million light-years later.

The photon must have had a path, because it made its way from the Andromeda Galaxy to the Earth, even if the path cannot meaningfully be assigned by an observer. — RussellA

You should really take a look at the article I linked earlier about John Wheeler—it directly challenges the idea that a photon must have had a definite path.

Wheeler’s cosmic delayed-choice experiment involves light from a quasar billions of light-years away being bent around a massive galaxy en route to Earth due to gravitational lensing. The light can reach Earth by two different paths—left or right around the lensing galaxy.

But here’s the twist: if we set up the experiment to detect which path the photon took, it behaves like a particle—one path. If we instead set it up to detect an interference pattern, it behaves like a wave—taking both paths.

And this choice of how we observe the photon is made now, on Earth—long after the photon has supposedly taken its “path.” The implication is that the photon didn’t have a determinate path until we made a measurement. So the assumption that it had a single, objective, space-time trajectory just doesn’t hold up under quantum scrutiny.

And really, that same principle has been illustrated with the much smaller-scale versions of the ‘delayed choice’ experiment e.g. here -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)It’s been clear from day 1 that Trump rules by decree. ‘Damn these pesky lawmakers with their inconvenient demands for ‘lawfulness’! They should know that I AM the law.” But now, Trump is practically ruling by whim. He will post his angry ruminations about tariffs at any hour of the day or night, with no regard for congressional oversight, and with the ability to drastically affect both the stock market and economics the world over. Then a day or a week later, post the exact opposite - or double it, or halve it. Whatever.

-

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?So there is nothing more to say about the metaphysics of reality beyond our best scientific models that supervene on the physical. — Apustimelogist

That sounds close to logical positivism—reducing reality to what our best scientific models can express, and treating everything else as non-serious. But positivism has been mainly abandoned due to its internal contradictions. Most notably, the claim that only empirically testable claims are meaningful isn’t itself an empirically testable claim so it is, as the saying goes, hoist by its own petard.

And more broadly, the assumption that metaphysics supervenes on physics is itself a metaphysical position—one that treats physical science as a final vocabulary. But that’s a philosophical stance, not a scientific result. But as you said before you will only be persuaded by an empirical argument, everything else, you say, is 'empty words'. Part of the same contradiction noted above.

The problem is that reality fails to give persistent indications of these things. But people still assert them, and naturalism (physicalism) is mostly a stance against that. — Apustimelogist

And that's because you look exclusively through the 'objectivist' stance that characterises scientific positivism.

I'm not OK with jumping to intellectual nihilism. — Relativist

So, you believe that 'idealism' (or in modern terms 'constructivism') is nihilistic, because it denies the external world? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Then how are you supposed to convince me — Apustimelogist

I put the case as best I can but understand that most people are not going to persuaded by it. The OP asks a rhetorical question, ‘does anyone really support a mind-independent reality?’ If a ‘mind-independent reality’ is to be questioned, how could that be made subject to empirical demonstration? Could it? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?So, really, you’re demanding empirical evidence for a philosophical criticism of empiricism. I’d like to oblige, but there’s no such thing, I’m afraid

-

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Given that you would agree that the universe had a history before any organism observed it, this is just meaningless. — Apustimelogist

‘Before’ is a concept. See this explanation..

‘I referred to his view qua idealist that, really, there was no world per se before the first perceiver, but also that science is correct in investigating ancient history, i.e. the world before perceivers. How could both of these claims be true? This is a general problem that idealism must address.’ -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?‘This dichotomy (of the Page Wooter mechanism) underscores the relational aspect of time in quantum mechanics: the experience of temporal evolution is contingent upon the observer’s interaction with the system. Such findings resonate with philosophical perspectives that consider time not as an absolute backdrop but as emerging from the interplay between observer and system.’

Agree? -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?But I cannot see how any phenomenological analysis any evidence for metaphysical claims. — Janus

It’s not that phenomenology provides evidence for metaphysical claims in the empirical sense, but rather that it reframes the whole question of metaphysics. Kant’s Critique was a critique of dogmatic metaphysics, but in doing so he introduced a transcendental metaphysics—one concerned with the conditions of the possibility of experience.

Phenomenology continues this line by grounding inquiry in intentionality—the structure of consciousness as always directed toward something—and in doing so, it opens a path to exploring meta-physical dimensions of existence without relying on the old ontological categories. It may not use the traditional metaphysical lexicon, but it’s still engaged in a metaphysical project: clarifying how being, meaning, and world come to presence for consciousness. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?My claim is merely that religious beliefs cannot be demonstrated to be true, that there is no evidence for the truth of any of them — Janus

‘Positivism is a philosophical approach that emphasizes the importance of observable, measurable phenomena and empirical evidence in gaining knowledge, generally rejecting claims that cannot be verified by scientific methods. It asserts that true knowledge comes from sensory experience and that knowledge is built through rigorous, objective research, separating the researcher from the subject.’

Also, I'm not saying that Armstrong should believe in religion, but I will say that materialist philosophy of mind rejects certain philosophical beliefs or attitudes that are characteristic of religious philosophies, generally - chief amongst them the immaterial nature of mind or the subject. The point about materialist philosophy of mind - Armstrong, Monod, Dennett, etc - is that only what is objectively real is considered real.

I do recognise the conflict between the philosophical outlook I'm trying to understand and convey, and philosophical naturalism, and I'm not shying away from that. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?the human perception of time would not exist if there was no mind. It's something of a tautology, but it's unwarranted to claim that our perception of time does not reflect something ontological. — Relativist

Your use of 'something ontological' simply means, you believe that time is real in a sense outside of any cognition of it. Even that usage is questionable. 'Ontology' refers to kind of being, or alternatively, a method for categorising types of substance or systems. What I really think you're saying is 'mind-independent'. I might agree that our perception of time reflects something real, but whatever that real is, it might well be outside of time - which we would have no way of knowing without measurement.

Consider this passage from science writer Paul Davies:

The problem of including the observer in our description of physical reality arises most insistently when it comes to the subject of quantum cosmology - the application of quantum mechanics to the universe as a whole - because, by definition, 'the universe' must include any observers.

Andrei Linde has given a deep reason for why observers enter into quantum cosmology in a fundamental way. It has to do with the nature of time. The passage of time is not absolute; it always involves a change of one physical system relative to another, for example, how many times the hands of the clock go around relative to the rotation of the Earth. When it comes to the Universe as a whole, time looses its meaning, for there is nothing else relative to which the universe may be said to change. This 'vanishing' of time for the entire universe becomes very explicit in quantum cosmology, where the time variable simply drops out of the quantum description. It may readily be restored by considering the Universe to be separated into two subsystems: an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe.

So the observer plays an absolutely crucial role in this respect. Linde expresses it graphically: 'thus we see that without introducing an observer, we have a dead universe, which does not evolve in time', and, 'we are together, the Universe and us. The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that. I cannot imagine a consistent theory of everything that ignores consciousness...in the absence of observers, our universe is dead'. — Paul Davies, The Goldilocks Enigma: Why is the Universe Just Right for Life, p 271

'The moment you say the Universe exists without any observers, I cannot make any sense out of that'. Do you know, incidentally, who Andrei Linde is? He's a Russian-American cosmologist and astrophysicist who is one of the authors of 'cosmic inflation' theory. He is interviewed by Robert Lawrence Kuhn of Closer to Truth on this point, which you can review here.

He's making the point that I'm making, and that Bergson makes, and Kant makes - time exists as an inextricable basis of our cognitive apparatus. That doesn't make it 'merely subjective' - from within that apparatus, we are able to measure time objectively and with minute accuracy, but that doesn't negate the necessity of their being a system of measurement nor a mind to measure it.

Physicalist philosophy projects that functionaity outward onto what you think is the existing world, the world as it would be without you are anyone in it, but you're viewing it through the VR headset that is the brain. -

What is real? How do we know what is real?You can happily indulge in the idiosyncratic use of "philosophical perspective" that you envision, but others need not agree — Banno

Of course. A large part of philosophy about managed disagreement. I've learned a ton from disagreeing with contributors here.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum