Comments

-

Is the real world fair and just?But then I won't be surprised if the cycle repeats because you seem to vacillate as to whether you want to make an ontological claim or merely an epistemological one. — Janus

This link:

You mean experimentally? - https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys3343 — apokrisis

Refers to Wheeler's 'Delayed Choice' experiment. I haven't read that particular article, but there's another on Discover Magazine about Wheeler and this famous experiment. That magazine article is called Does the Universe Exist if We're Not Looking?

That seems to be making 'an ontological claim'. Or wait - is it an 'epistemological claim?'

You tell me. -

Is the real world fair and just?So you acknowledge that unperceived things exist, and you are only denying that we can see things as they are when unperceived? — Janus

If you look at the OP again, you will notice that I've worded it very carefully. I will draw attention to a specific passage:

Let me address an obvious objection. ‘Surely “the world” is what is there all along, what is there anyway, regardless of whether you perceive it or not! Science has shown that h. sapiens only evolved in the last hundred thousand years or so, and we know Planet Earth is billions of years older than that! So how can you say that the mind ‘‘creates the world”’?

As already stated, I am not disputing the scientific account, but attempting to reveal an underlying assumption that gives rise to a distorted view of what this means. What I’m calling attention to is the tendency to take for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution. This oversight imbues the phenomenal world — the world as it appears to us — with a kind of inherent reality that it doesn’t possess. This in turn leads to the over-valuation of objectivity as the sole criterion for truth. By ‘creating reality’, I’m referring to the way the brain receives, organises and integrates cognitive data, along with memory and expectation, so as to generate the unified world–picture within which we situate and orient ourselves. — Wayfarer

Beyond that, I'm unwilling to try and re-state and re-explain what I think is stated and explained quite clearly in the OP.

@Banno - 'taking for granted the reality of the world as it appears to us, without taking into account the role the mind plays in its constitution' is what I took to be compatible with 'the myth of the given', although I didn't have that in mind when I composed it. -

Does physics describe logic?I am fascinated by disaster tourism....There is nothing more fun than a complete mess — Tarskian

That explains a lot ;-) -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

The only "deep state" is Project 2025 (i.e. The Heritage Foundation + The Federalist Society). Take your meds, dude. Roevember is coming! :victory: — 180 Proof -

Is the real world fair and just?So once the direct route is accepted as forbidden to us, then what becomes the best indirect route? That is what pragmatism is about. We can subtract the psychological individual from the equation and make it about a dispassionate community of reason. — apokrisis

I don't know if 'forbidden' is the right word.

There's a relationship between 'subtracting the psychological individual' and the idea of detachment or disinterestedness. The 'dispassionate community of reason' is what the scientific community aspires towards, striving for objectivity and minimizing personal biases and emotions to gain an accurate understanding of the natural world through empirical observation, repeatability, and falsifiability. Detachment in the earlier, pre-modern sense esteemed by philosophical spirituality demands self-effacement and the abandonment of personal desires and ego to achieve insight into universal truths. They're historically related, in that the scientific developed out of the pre-modern, but as it did so, it also assumed a more anthropocentric perspective. (Maybe that's discussed in the Peter Harrison book on the foundations of science. )

There is the myth of the given; that mere observation, uninterpreted, is a given foundation for knowledge. — Banno

I see your point, but it's not too remote from my argument. My bad for bringing up Sellars. But nowhere have I said 'there is no world', only that we can't see it as if we were not a part of it, that the objective stance is treated as if it were an absolute, which it isn't. -

Is the real world fair and just?the judgement that there are (or are not) such realities is an expression of a perspective. — Janus

But what can be expressed about anything without bringing a perspective to bear on it? As soon as you start to talk about 'whether the tree falls in the forest if no-one is there to hear it', you're already bringing a perspective to bear. As soon as you say there are unseen planets and unknown vistas, then you're already bringing a perspective to bear. The only way not to do that is to not say or think anything whatever.

Again, I'm making the distinction that Kant identified about the compatibility of empiricism and transcendental idealism. In Kant's philosophy, there is no inherent conflict between empiricism and transcendental idealism because they address different aspects of knowledge. Empiricism pertains to the content of our experiences, emphasizing that all knowledge begins with sensory input. Transcendental idealism, on the other hand, concerns the conditions that make such experience possible, positing that our minds actively structure and organize sensory data through a priori categories and forms of intuition, such as space and time. Thus, while empiricism provides the raw material for knowledge, transcendental idealism explains the framework within which this material is synthesized and understood, harmonizing the two by showing how empirical data is shaped by the mind's innate structures to produce coherent experience. That is the framework you can't get outside of, yet this is what you posit when you imagine a world with no subject in it.

I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrine that they are all together to be regarded as mere representations and not things in themselves, and accordingly that space and time are only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves. To this idealism is opposed transcendental realism, which regards space and time as something given in themselves (independent of our sensiblity). The transcendental realist therefore represents outer appearances (if their reality is conceded) as things in themselves, which would exist independently of us and our sensibility and thus would also be outside us according to pure concepts of the understanding. (CPR, A369)

Time and space are themselves projected by the mind onto the cosmos. They're not real independently of your perception of them.

It is why Kant says that we can't know the Universe (or object) as it is in itself, although @Banno has already declared that he rejects the idea (whereas I think he simply doesn't get it.) The "thing in itself" (which I'm saying is 'the Universe with no observers) represents the reality that lies beyond our perceptual and cognitive reach. This underscores the limits of human knowledge and reinforces the idea that our understanding is always shaped by the conditions of our cognition, making any direct knowledge of the "thing in itself" both impossible and meaningless within our conceptual framework.

Now I question Kant on that score, and there have been plenty of objections raised by generations of subsequent scholars. But I still say the substantive point remains.

There was a mention earlier in this thread about Kastrup's 'mind-at-large', and my questioning of that in a Medium essay. On further reflection, I am beginning to see that this could be conceptualised as 'the subject' or 'an observer' in a general sense. It doesn't refer to a particular individual, nor to some ethereal disembodied intelligence that haunts the Universe. But I wonder if it might also be plausibly understood as represented by the 'transcendental ego' in Kant and Husserl. Also, quite plausibly, the role of 'observer' in physics, which is never something included in the mathematical descriptions.

state a clear position. — Janus

What is clear from ten years of interactions, is that you don't understand what I write despite repeated efforts on my part to lay it out as clearly as I can. I'm about at the end of my tether as far as you're concerned. -

Is the real world fair and just?The irony is that someone like Wayfarer who doesn't want to acknowledge that many things have happened, are happening and will happen that we can never know about, — Janus

A constant reminder that incomprehension of an argument doesn't constitute a rebuttal.

So though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle.

Hence there is no need for me to deny that the Universe is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe exists independently of any particular mind. — Wayfarer

sages can "directly" know "what is really going on". — Janus

I had Parmenides in mind, but obviously a very difficult text to fathom. I was recently musing whether Krishnamurti has a similar insight to Parmenides:

If you see "what is" then you see the universe, and denying "what is" is the origin of conflict. The beauty of the universe is in the "what is" and to live with "what is" without effort is virtue. — Krishnamurti -

Is the real world fair and just?Perhaps Wayfarer could take you on a Zen retreat? — apokrisis

I myself never went to a specifically Zen retreat, although I did do others, including the arduous 10-day Goenka retreat in the past. Anyway I don't have the temperament or self-discipline required for Zen, I'm what Buddhists call bombu (the foolish ordinary man. )

That Nature quote - sure, I’ve been hearing about the 4E approach - enactive, embodied, embedded, extended. Vervaeke often talks about that. Kant is not the last word but there are aspects of his philosophy that remain essential (the fifth E?)

The thing in itself is left out of the equation. And science makes a big mistake in seeming to claim otherwise. But while science often does seem to claim this, along with the lumpen realists, science just as much understands in great detail the way it is all a self-interested cognitive construct that we dwell in as our personal space. That other semiotic view has always been there and has grown stronger in recent years. — apokrisis

Totally. I get there are many scientists who have that insightful approach. I’m arguing more against the residue of old-school materialism which is a very different thing, and still a very influential stream of thought. It’s like ‘the greening of America’, the emergence of ‘Consciousness III’ as that book had it. I’m pretty well on board with all the biological theorists you’ve introduced me to, as they’re generally not what I have in mind when I criticize ‘scientism’.

in reply you seem to hold that there are no true statements, only propositional attitudes. — Banno

I have acknowledged that there are empirical facts that can be objectively demonstrated. It's not as if they’re mind-dependent in depending on my believing them. Fire burns, medicine heals, knives cut and those who say otherwise are objectively mistaken. As I’ve said, Kantian philosophy allows for the consanguinity of empirical facts with transcendental idealism. But the empirical realm is itself constituted by and in the transcendental subject (i.e. some mind, some observer, not myself or a particular individual). -

Is the real world fair and just?I never did call it into question. What I call into question is a 'mind independent world'. Reality contains an ineliminable subjective pole or element which in itself is not amenable to objective description. You say that, like me, you're opposed to 'scientism' but you don't say on what grounds. From my perspective, my argument shows how 'scientism' always contains a blind spot, as detailed in the essay I often refer to, The Blind Spot of Science is the Neglect of Lived Experience, by Thompson, Frank and Gleiser (now a book.)

-

Is the real world fair and just?The "reality" of the world - that some things are the case - cannot be called into question. — Banno

Why the scare quotes around reality?

At issue is whether the world is mind-independent or is not. You claimed:

There are three problems - the puzzle of other people, the fact that we are sometimes wrong, and the inevitability of novelty - each of which points to there being meadows and butterflies and other people, despite what you have in mind. I think you know that idealism won't cut it." — Banno

And I think that what you have in mind when you say that, is not what I mean by the term 'idealism', although I quite agree it's not worth another go-around. -

Is the real world fair and just?You are disparaging of "The world is all that is the case", but have offered nothing coherent, no alternative and certainly not a refutation. — Banno

I said, in declaring this, you are basically starting that the empirical world is a given, the reality of which can't be called into question. I said this is subject to the criticism usually described as the myth of the given. I regard that as a coherent criticism of your common-sense realism.

I know we're talking past one another. From my side, I feel I offer arguments, and they're often ignored. From your side, what I think are arguments seem to be meaningless or pointless. Perhaps our perspectives are in some sense incommensurable. -

Does physics describe logic?One of those possibly pseudo-questions which may be sophistry; but, in your opinion do you think physics describes logic? — Shawn

You need logic before you can study physics. As was said already. (This incidentally is a cogent argument against physicalism as logic is used to construct physics, but not vice versa.)

Does physics entail logic? — Fire Ologist

I think there's a fascinating connection between Galileo's 'book of nature is written in mathematics' and the ability of modern mathematical physics to model and predict hitherto unknown natural processes. Through quantification, which comprises the ability to capture the measurable attributes of objects and forces, we are able to apply abstract mathematical methods, which often produce startingly novel results (per Eugene Wigner's The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences.)

That would require a usable theory of physical reality, which we don't have. We just have a collection of stubbor — Tarskian

Isn't a lot of what you write based on the fact that science doesn't explain science, mathematics doesn't explain maths, and so on? I mean, physical principles, such as Newton's Laws of Motion, and related mathematical techniques including calculus have been deployed to enormous effect across a huge range of applications. But Newton's laws don't explain why F=MA - nor do they need to. Can't we get by without knowing that?Isn't it sufficient to know how they work and how to apply them? -

Is the real world fair and just?If the world reveals itself to the degree it can frustrate our desires, then dialectically this epistemology of truth demands the existence of those desires as the other half of its egocentric equation. — apokrisis

'Not my will, but thine, oh Lord' is one way of solving that problem.

Incidentally I did a search on 'biosemiosis and idealism' which predictably returned a number of interesting articles, the top one of which is called The Idealistic Elements of Modern Semiotic Studies. So far it seems quite an approachable read. It starts with this quotation:

“All reality is subjective appearance.

This must constitute the great, fundamental

admission even of biology.”

—Jakob von Uexküll, Theoretical Biology

Which seems congenial to my p-o-v. Much of what I've read so far is on the contribution of Kant to Uexküll vision of the 'umwelt' but I'm still going.... -

Feature requestsPerhaps edits should only be allowed for a certain amount of time. — Leontiskos

I'd agree with that, as it has been the practice for every other forum I've joined. I make use of the ability to edit but generally try and observe a rule of not editing any post after it has been replied to or quoted. I think many of the other points are up to the discretion of the mods, although I don't think any of them bad ideas. -

Is the real world fair and just?Make yourself a coffee. I know you have plenty of cups, even if I can’t see ‘em.

-

Is the real world fair and just?No. I'm a bit surprised you think this of what has been said. The world is what is the case. — Banno

Well, you said:

The world just is as it is, regardless of what you think of it — Banno

Isn't that just another way of saying that its reality is a given? What else could it possibly mean?

Notice the difference between the world being what is the case, and the idealist view that the world is what we believe, know, intuit, hope, doubt to be the case. — Banno

But I've already addressed that very point:

this is something much deeper than a matter of belief. The cognitive process of world-construction is subconscious or subliminal. I'm talking about our whole 'meaning-world', the entirety of our sense of self-and-world. That is created by the mind but not the conscious ego or self. — Wayfarer

According to the classical tradition of philosophy, we do not see 'what is really the case'. Seeing what is really the case is the hallmark of sagacity, and it's generally considered very rare. We are too self-centred and our cognition is distorted by innummerable biases (encapsulated under the heading 'avidya' in Indian philosophy). The purpose of philosophy is to dispel the darkness of ignorance, to overcome our unconsciously self-centred view of the world. Science actually got it's start from this very same intuition.

We seem to see directly the material event - the bruteness of the stone we kick or cup we smash - but not so directly the global organising purpose or finality involved. — apokrisis

:100: -

Is the real world fair and just?(2) that no world can be imagined in which this is not the case.

To imagine is to invoke this "subjective" pole; so this looks to be tautologous. — Banno

You'll notice I struck out 'imagined' and replaced it with 'real'.

I'm showing how language works, rather than defending naive realism. — Banno

Of course you're defending naive realism. That is made particularly obvious by your homely choices of kitchen utensils to stand in for 'the object'.

The world just is as it is, regardless of what you think of it — Banno

It's a given, right? -

Is the real world fair and just?You have been challenged to explain how it is that we all perceive the same things, — Janus

I don't deny the reality of objects. Heck, I myself have coffee cups, and some of them are in the dishwasher even as I write this. I'm not arguing for solipsism. My claim is that (1) reality has an ineluctably subjective pole, and (2) that no world can beimaginedreal in which this is not the case (3) that this subjective pole or ground is never itself amongst the objects considered by naturalism, and (4) that the emphasis on objectivity as the sole criteria for what is real is deeply mistaken on those grounds. -

Is the real world fair and just?That there is a world that may be different to our beliefs is shown, not said. It's not an "inference". It's demonstrated by the cup coming out of the dishwasher clean, and all manor of other interactions, with medium sized smallgoods and whatever else you might find. — Banno

That was the very point of the passage from Berkeley's dialogues that I provided, in which this exact objection is made to Philonous/Berkeley. Hylas says 'if all you admit is the reality of ideas, then how come your ideas can be wrong, like when a stick in the water appears to be bent?' It's the same objection you're offering here, that our beliefs can be different to what we discover about the world. But notice that Philoonous qua idealist does have an answer to that, along the lines of coherentism.

Besides, this is something much deeper than a matter of belief. The cognitive process of world-construction is subconscious or subliminal. I'm talking about our whole 'meaning-world', the entirety of our sense of self-and-world. That is created by the mind but not the conscious ego or self. It goes much deeper than that, it is a process which informs all living things.

I think what you're instinctively defending is naive realism (no pejorative intended). You are shocked by the questioning of the reality of the sensable world. Damn it, can't he just see that my cups are in the cupboard even with the door closed?!? That they don't dissappear when I can't see them?!? I'm not saying that, but that is how you're reading it. -

Is the real world fair and just?So, the world that you claim exists independently of any interpretation - how do you demonstrate the existence of that?

-

Is the real world fair and just?So please correct this Chat input:

The 'myth of the given' is a concept in philosophy, particularly within epistemology, that critiques the idea that there are certain immediate, self-evident pieces of knowledge that serve as a foundation for all other knowledge. This concept was primarily developed by philosopher Wilfrid Sellars in his essay "Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind" (1956). Sellars argued against the notion that there are "given" elements in experience—such as sense data, raw feels, or basic perceptual inputs—that can serve as an unquestionable foundation for knowledge.

Sellars maintained that any attempt to base knowledge on such "givens" fails because even these purportedly immediate experiences are influenced by our conceptual framework. For example, seeing a red apple is not just a matter of raw sensory input but involves recognizing and categorizing the experience within a framework of concepts and beliefs.

According to Sellars, all knowledge is theory-laden; it is shaped by the language, concepts, and theories that we use to interpret our experiences. Thus, the supposed "givens" are not independent of our conceptual understanding. This view challenges traditional empiricism, which often relies on the idea of foundational, immediate knowledge derived from sensory experience.

The critique of the myth of the given has significant implications for epistemology. It suggests that knowledge cannot be grounded in indubitable perceptual inputs but must instead be understood as a network of interdependent beliefs and concepts. This idea has influenced various areas of philosophy, including debates about foundationalism, coherentism, and the nature of perception and understanding. -

Is the real world fair and just?But you will take this as implying that there is no world without mind. It doesn't. It implies only that there is no interpretation without mind.

You always take one step further than your argument allows. — Banno

No - because 'the world' that you imagine exists in the absence of any mind, is not 'a world'. The etymology of the noun 'world' comes from an old European word for 'time of man'. No mind, no world - not because the world ceases to exist, but it has no form, perspective, duration, and so on.

In order for you to establish what the world would be outside your cognition of it, you would have to stand outside that whole process of cognition. (This is even recognised in analytical philosophy, in Sellars' 'the myth of the given'.)

Shocking but true. -

Is the real world fair and just?Any interested party, but as I said yesterday, I recognise a brick wall when I see one ;-)

-

Is the real world fair and just?Again, referring to Charles Pinter's book

The book’s argument begins with the British empiricists who raised our awareness of the fact that we have no direct contact with physical reality, but it is the mind that constructs the form and features of objects. It is shown that modern cognitive science brings this insight a step further by suggesting that shape and structure are not internal to objects, but arise in the observer. The author goes yet further by arguing that the meaningful connectedness between things — the hierarchical organization of all we perceive — is the result of the Gestalt nature of perception and thought, and exists only as a property of mind. These insights give the first glimmerings of a new way of seeing the cosmos: not as a mineral wasteland but a place inhabited by creatures. — Mind and the Cosmic Order: How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why this Insight Transforms Physics

You see, this also provides a plausible grounds for why the 'unreasonable efficiency of mathematics in the natural sciences' and Kant's 'synthetic a priori'. As our cognition naturally operates in terms of gestalts, which are fundamentally cognitive in nature, and both logic and mathematics pertain to the relation between gestalts. So there's no longer a question of how what is apparently 'internal to the mind' can be so accurate with respect to 'the external world', as on one level, they're united. -

Is the real world fair and just?Semiotic logic says reality has irreducible complexity. You can't get simpler than – as Gestalt theory puts it – the relational view that is a figure and its ground. — apokrisis

Still struggling with how this can be meaningfully said to be physical in nature. The appeal of atomism is the ostensible 'indivisible unit' which represents in atomic form 'the unchanging'. To say that reality is 'irreducibly complex' seems to omit something fundamental to metaphysics, the unconditioned or unmade.

And how is this incompatible with, say, Kastrup's form of analytical idealism?

Bergson.Henri Bateson — Gnomon

It remains that the universe is fair and just only if those "complex brains & minds" make it so - is that right? — Banno

It's only to rational sentient beings that the question matters.

the basic features of the world are not mind-created, but mind-recognized. — Janus

There are no features without minds. In the absence of minds the universe, such as it is, is featureless, formless, and lacking in any perspective. -

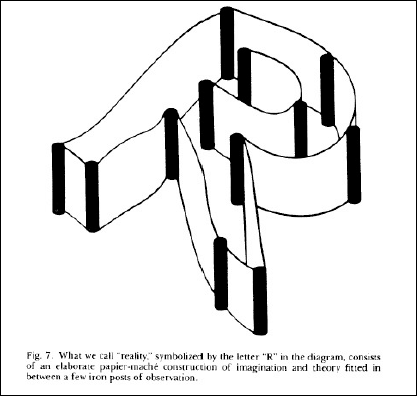

Is the real world fair and just?I want to backtrack to the post about the Wheeler diagram and a response to it. The response was:

The point is epistemic. And it reflects the semiotic fact that the mind must reduce reality to a system of signs. The world is a blooming, buzzing confusion of noise and we must distil that down to some orderly arrangement of information. A set of counterfactuals that impose a dialectical crispness on the vagueness of our experience.

So in Gestalt fashion, we turn sensory confusion into perceived order by homing in on critical features that would distinguish and R from an E or a K. We have to be sensitive to the fact that Rs have this loop that Es leave open. This becomes a rule of interpretation for when we start having to deal with a real world of messy handwriting and wild fonts. We have to see information that was meant to be there according to the rules and so ignore the variation that is also in some actual scribble or fancifully elaborate font.

Our interpretative experience of even the alphabet, let alone the world, has this epistemic character. — apokrisis

So, I agree, I think it exactly the point of the diagram. As the response notes, the mind creates gestalts, meaningful wholes, by which recognise not only letters, but also the basic features of the world. Gestalts are fundamental to cognition. Here I also want to mention Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles Pinter. His basic thesis is likewise that cognition operates in terms of gestalts, those elements, corresponding to categories of animal sensation, which it carves out from the background and recognises as meaningful wholes. This, he says, operates even in insects (citing research to this effect)

Everything you see, hear and think comes to you in structured wholes: When you read, you’re seeing a whole page even when you focus on one word or sentence. When someone speaks, you hear whole words and phrases, not individual bursts of sound. When you listen to music, you hear an ongoing melody, not just the note that is currently being played. Ongoing events enter your awareness as Gestalts, for the Gestalt is the natural unit of mental life. If you try to concentrate on a dot on this page, you will notice that you cannot help but see the context at the same time. Vision would be meaningless, and have no biological function, if people and animals saw anything less than integral scenes. — Chapter 3, Abstract

The question I want to ask is the sense in which gestalts are irreducible. (Maybe it’s here where I'm said to be constantly 'sliding between the epistemic (what is knowledge) and ontological (what are the fundamental constituents of the world.)) But if gestalts are fundamental to cognition, how can you get outside them to see what is causally prior to them? And isn’t the so-called ‘wave function collapse’ exactly analogous to the forming of a gestalt where there was previously only an array of probabilities? It must surely be something like that for Wheeler’s diagram, as it was presented in the context of his discussion of his baffling ‘delayed choice’ experiment. But then, this analysis is naturally holistic rather than reductionist, as in this analysis the fundamental units are not physical but cognitive. -

Is the real world fair and just?I may be idealist, but I recognize a brick wall when I encounter one.

I have outlined many times how biosemiosis now adds the epistemic cut to the business of quantum interpretation — apokrisis

Indeed, I didn’t know what biosemiosis meant when I joined this forum, and I’ve come to appreciate it. But there’s also a spectrum of views in that community, I’ve learned, and not all of the scholars in that field are as committed to physicalist principles. I’ve found a recent book on biosemiotics and philosophy of mind which I mean to get back to. Meantime, grandad is being paged ;-) -

Is the real world fair and just?It might help to try and look at why we keep coming back to these same arguments. I think it to do with the vanity of small differences — Banno

It also had to do with ignoring much of what I’ve been saying. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)And Republicans complain that Trump is ‘falsely accused’ of threatening democracy….. :chin:

-

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Christians, get out and vote, just this time. You won’t have to do it anymore. … You got to get out and vote. In four years, you don’t have to vote again. We’ll have it fixed so good you’re not going to have to vote. — Trump

Believer’s Summit, Florida.

Realizing the implications, a Trump spokesman later helpfully added ‘of course he didn’t mean it.’

Of course. -

Is the real world fair and just?There is still this tendency to slide from an epistemic to ontic position in your choice of words. — apokrisis

Between the iron posts and the paper maché, you mean? -

Is the real world fair and just?An understanding is an Umwelt. It is the manufacturing, or co-dependent arising, of the subjective and the object, the self and its world, as the one cohesive dialectic.

There is no ontological self that is the seat of consciousness. That is as much a useful epistemic construct as the world in which this self sees itself living within. — apokrisis

Just as I said. Self and world are co-arising, just as posited by enactivism. That is why we see the convergence between phenomenology and Buddhism in The Embodied Mind.

You didn't take the time to set out what it is you want me to take from the extended quote — Banno

Apologies if that was not clear. It was posted in response to your:

there is a difference between how things are and how we believe they are. A difference between how they are and how we say that they are. A difference that tends to dissipate in idealism. A difference that explains what it is to be mistaken. — Banno

That argument was used against Berkeley: if our grasp of appearances can be mistaken, then how can he argue that the ideas and impressions which he claims constitute our knowledge should be trusted? How can there be a distinction between ‘what appears the case’, and ‘what is the case’ if all we have are our ideas?

So the passage from Berkeley’s imaginary dialogue was provided to illustrate how Berkeley deals with that criticism.

I think we agree that there is a world, and that we have what philosophers call intentional attitudes towards that world, but you put all the emphasis on those attitudes, as if the world were not also part of what is going on — Banno

As I said in the essay, there is no need for me to deny that there are ‘planets unseen by any eye’, to quote myself. Again, the question is the purported ‘mind-independence’ of the objective domain. As I’ve acknowledged many times already, there are different levels of understanding - in the empirical sense, obviously the world and everything in it is independent of my mind, unknown to me. Heck, I only know about half a dozen people in my street. But on a deeper level, ‘the world’ is a construct - not a confabulation, not an hallucination, but a construct of the mind. That is the sense in which it’s not ‘mind-independent’. And as soon as you posit ‘an unknown object’ - the tree that falls in the forest - you’re already bring a perspective to bear, attempting to illustrate the point with respect to some ‘intentional object’. (This incidentally I take to be in conformity with Kant’s understanding of the distinction between reality and appearance.)

The philosophical point behind the argument, is that naturalism tends to regard ‘mind-independence’ as a criteria for what is real. It attempts to arrive at an understanding of what exists in the absence of any subjective elements whatever. In that world-picture, we view ourselves as objects, and miniscule, insignificant objects at that, epiphenomenal occurrences thrown up by unknowing physical processes in the vast universe. That is what I take scientific realism to be advocating. In addition to that physicalism posits that the mind-independent realm comprises physical elements, which are purportedly the objects of physics itself. That is what I’m arguing against. Hence the emphasis on the ‘observer problem’ in physics, which directly undermines that formulation of physicalism.

Arguably, science itself is now moving beyond that formulation, but regardless, that is what I have in my sights. -

Is the real world fair and just?Our interpretative experience of even the alphabet, let alone the world, has this epistemic character. We must divide the confusion dialectically into global formal necessity and local material accident. That is then how we can “decode” reality. That is how we can construct an “understanding”. — apokrisis

No need for the scare quotes around understanding. Which pretty well illustrates the point of the ‘mind-created world’. -

Is the real world fair and just?Again, there is a difference between how things are and how we believe they are. A difference between how they are and how we say that they are. A difference that tends to dissipate in idealism. A difference that explains what it is to be mistaken. — Banno

Say we see an oar in water and it appears bent to us. We then lift it out and see that it is really straight; the bent appearance was an illusion caused by the water's refraction. On Philonous' (i.e. idealist) view, though, we cannot say that we were wrong about the initial judgement; if we perceived the stick as bent then the stick had to have been bent. Similarly, since we see the moon's surface as smooth we cannot really say that the moon's surface is not smooth; the way that it appears to us has to be the way it is. Philonous has an answer to this worry as well. While we cannot be wrong about the particular idea, he explains, we can still be wrong in our judgement. Ideas occur in regular patterns, and it is these coherent and regular sensations that make up real things, not just the independent ideas of each isolated sensation. The bent stick can be called an illusion, therefore, because that sensation is not coherently and regularly connected to the others. If we pull the stick out of the water, or we reach down and touch the stick, we will get a sensation of a straight stick. It is this coherent pattern of sensations that makes the stick. If we judge that the stick is bent, therefore, then we have made the wrong judgement, because we have judged incorrectly about what sensation we will have when we touch the stick or when we remove it from the water. — Dialogue between Philonious and Hylas, Berkeley -

Is the real world fair and just?What, you say particle mechanics and wave mechanics both seem to apply? — apokrisis

Very rich post with much that could be commented on, but I wonder if you might provide an interpretation of this graphic. I’ve posted it here previously, it’s from John Wheeler’s paper, Law without Law:

The caption reads, ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

What do you think the point of that simile is? Do you think it suggests something similar to what I’m proposing as the ‘mind-created world’?

@Banno -

Is the real world fair and just?Lao Tse is considerably less loquacious than Hegel and the basis of a living philosophy.

Bohr as you know incorporated the ying-yang symbol into the family Coat of Arms that was crafted when he was knighted by the Danish Crown.

Bohr regarded his ‘principle of complementarity’ a major discovery in its own right.

This is quite a useful article - https://phys.org/news/2009-06-quantum-mysticism-forgotten.html

It points out that the pioneers were deep thinkers - cultured Europeans who understood philosophy. Schrödinger and Heisenberg both wrote perceptively on physics and philosophy. Post-war the action shifted to the US, ‘big science’ and military/industrial research. -

Is the real world fair and just?The Statement can only be made by an observer — Banno

I said ‘any judgement regarding what exists’. The position I’m defending is near to Berkeley’s esse est percipe, but the way I put it is that nothing exists outside a perspective.

Optical illusions and mistaken perceptions such as ‘the bent oar’ are discussed by Berkeley. I’ll dig up the ref although not right now.

Why do you think there is and has been an argument in physics as to ‘what is real’, were the issue so simple as you appear to believe? What is the argument about, do you think? -

Is the real world fair and just?Hence ontic structural realism as the new Platonic sounding metaphysics that has arisen out of a contemplation of gauge symmetry and quantum field theory. — apokrisis

I’ve read about those guys but I really don’t like them so far.

But instead of celebrating this quite remarkable success in fundamental science, you ... complain we're "not there yet". — apokrisis

Complaint?

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum