Comments

-

Indirect Realism and Direct Realismit is impossible to directly receive that which is not real, for we would never be aware of an affect. — Mww

Seeing a beautiful sunset affects an observer differently to seeing a sunset.

Does this mean that abstract concepts such as beauty are real? -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism@Michael

NOTES ON INDIRECT REALISM

Chain of events

Everyone seems to agree that there is a chain of events prior to perception. For example, light from the sun hits an object, part of the light is absorbed by the object and part reflected, a wavelength then travels though space to the eye of an observer, this causes an electrical signal to travel along the optic nerve from the eye to the brain where it is somehow processed, thereby enabling the mind to perceive the colour red.

There is a chain of events going back in time prior to my perceiving the colour red, which if disrupted, would have prevented the perception of the colour red

It is a fact that I directly perceive sensations, such as the colour red, an acrid smell, a bitter taste, a sharp pain or a screeching noise. These sensations are sometimes called qualia.

The expressions "I see the colour red", "I perceive the colour red", "I am aware of the colour red", "I am conscious of the colour red" and "I sense the colour red" seem synonymous.

It is accepted that each link in the chain can be of a different kind, in that an electrical signal up the optic nerve is of a different kind to a wavelength of 700nm that precedes it. It is also a fact that there is no information within a subsequent link in the chain that can determine the preceding link in the chain, in that the wavelength of 700nm could have been equally caused by light reflecting off a rose, a strawberry, a lizard, a frog, a painting, a television screen or a Christmas light. Each link in the chain is an intermediary between sunlight hitting the rose and the perceiver perceiving the colour red

There is the question of terminology regarding mapping, presenting and representing. We perceive the colour red because light was reflected off a rose. We can say that "the colour red represents a rose", "the colour red is mapped to the rose" or "the perceiver is presented with a rose and perceives the colour red", but as with most words in language, all these are figures of speech rather than literal descriptions.

The Perceiver and what the perceiver perceives

It is important to note that the "I" that is perceiving the colour red is not separate to the colour red that is being perceive, but rather the perceiver and perceived are one and the same thing. If otherwise, would lead into the infinite regress homunculus problem.

It cannot be the case that what the perceiver is perceiving is external to the perceiver, such as sense data or an intermediary, because sooner later, in order for there to be perception at all, what is being perceived must be internal to the perceiver. The perceiver and what is being perceived are two aspects of the same thing.

As John Searle explains in The Philosophy of Perception and the Bad Argument

The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

The cause of the perception

So the perceiver and the thing being perceived are two aspects of the same thing and neither external to the other. But something cannot come from nothing. The perception cannot have been spontaneously self-created out of nothing. There must have been a cause, even if the cause is unknown. As my perception of the colour red cannot have been caused by the colour red being perceived, because these are two aspects of the same thing, the perception must have caused by something external to not only the perceiver but also the thing being perceived. The cause can only have been a prior link in the chain of events going back in time.

The relation between what is perceived and the unknown cause of such perception

Humans commonly name the unknown cause of a sensation after the known effect. For example, the cause of seeing a red colour is described as a red object, the cause of a bitter taste is named as a bitter food, the cause of an acrid smell is named acrid smoke, the cause of hearing a loud noise is named a loud noise and the cause of a painful sting is named a sting. Although the sensation is real, the named cause is fictive.

We can only know about an object from its properties. If an object had no properties we would not know about it. For example we may describe a rose as having the properties of being red in colour, being circular in shape and being sweet in smell, yet as Bertrand Russell pointed out in his Theory of Descriptions, it is more correct to say that there is something that has the properties of being red, being circular and being sweet. There is no Platonic thing that is a rose that exists independently of its properties. The rose is no more than its set of properties. Therefore, to say "I see a red rose" is a figure of speech for the more literal "I see something that has the colour red, has a circular shape and a sweet smell, and that this something with these properties has been named "a rose"".

In the expression "I see a red rose", red is an intrinsic part of what a rose is, not an extrinsic property. We may say that red is an adjective qualifying the noun rose, but must remember that this is a linguistic convenience, not a literal description of the relationship between the object rose and its property redness.

Adverbialism

Therefore, as regards the Adverbialist, rather than say "I perceive a red, circular and sweet rose", it is more correct to say "I see something that has the properties of red, circular and sweet and that this something has been named rose".

Therefore, for the Adverbialist, as the perceiver of the sensation and the sensation are two aspects of the same thing, the expression "I see a red, circular and sweet rose" may be replaced by "I perceive redness, circularness and sweetness" and "this something having the properties of redness, circularness and sweetness" has been named "a rose"". For the Adverbialist, redness, circularness and sweetness are adverbs qualifying the verb "to perceive".

Adverbialism is consistent with Bertrand Russell's Theory of Descriptions. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe trees are in the Mississippi delta backwaters.................I could take you there and show you in person..................None of those things and none of those places are in my mind. — creativesoul

Suppose we are both in Mississippi.

I agree that in a mind-independent world are real things, in that they can physically affect me. They can cause in my sensations sharp pains, acrid smells, sweet tastes, loud noises and colours.

You say that the place Mississippi does not exist in the mind, and yet the original Mississippi Territory was only created by the U.S. Congress in 1798.

Are you saying that the place Mississippi existed before the US Congress named it in 1798?

How did the US Congress know the extent of the territory of Mississippi before the extent had even been written down?

===============================================================================

What I'm saying is that it is possible for a capable creature to directly perceive green cups but because they do so by means of ways that they are completely unaware of, they're not conscious of perceiving. They're just doing it. — creativesoul

I think that the expressions "I see a green cup", "I perceive a green cup". "I am aware of a green cup" and "I am conscious of a green cup" are synonymous.

As an Indirect Realist, I agree that in the first instance I directly perceive a green cup. I don't perceive myself perceiving a green cup, I am not perceiving an image of a green cup and I am not perceiving a representation of a green cup.

Subsequently, however, I can begin to apply reason about what I have perceived, and ask myself what exactly was it that I had perceived. Had I perceived a green cup as it was in the world, had I perceived an image of a green cup, had I perceived a representation of a green cup or had I perceived a cup greenly. However, I agree that all these all philosophical questions don't detract from the point that in the first instance I directly perceive a green cup.

===============================================================================

House cats can see green cups in cupboards and have no idea that they're called "green cups". — creativesoul

How do you know what is in the cat's mind, that the cat sees the cup as green, rather than red or blue?

===============================================================================

If the object has no inherently existing mind-independent property of color to speak of, then it makes no sense to accuse either one of you of not seeing the object 'as it really is'(whatever that's supposed to mean). It's appearing green to you and blue to them makes no difference - if the object has no inherently mind independent property of color. — creativesoul

As an Indirect Realist, I agree that objects in the world don't have the mind-independent property of colour, but the object must have some property otherwise no-one could see it. It could well be the property of being able to reflect a particular wavelength of light, such a red rose has the property of being able to reflect the wavelength of 700nm when illuminated by white light.

I agree that the wavelength of 700nm may have different effects on different people, in that, for example, I may perceive the colour green whilst another person may perceive the colour blue. But no-one will ever know, as it is not possible to look into another person's mind.

The question is, if I perceive the object as having the property green, but in fact the object has the property of being able to reflect a wavelength of 700nm, in what sense am I directly perceiving the object?

===============================================================================

Trees are in the yard. Concepts are in the language talking about the yard. Both are in the world. Concepts are in worldviews. Cypress trees are in the backwaters of the Louisiana delta. — creativesoul

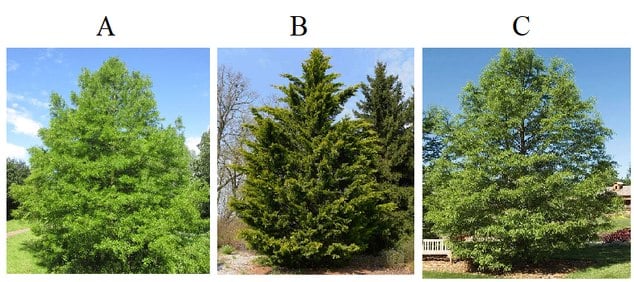

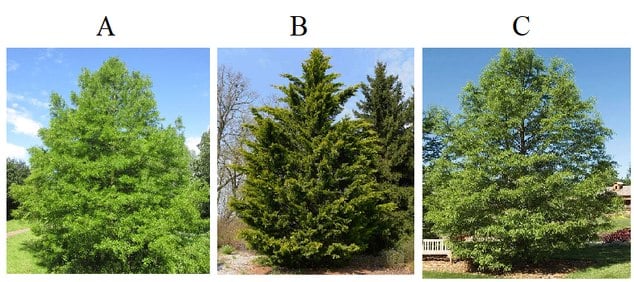

If Cypress trees exist in the world independently of any human mind, then it should be obvious to someone who doesn't know the concept of a Cypress tree, that A and B are the same thing and A and B are different to C

Yet that is obviously not the case. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI don't understand why you don't understand what I'm asking and I don't know how to explain it in any simpler terms. — Michael

I generally agree with what you say, so I apologise if I'm missing something. Perhaps I'm thinking of my glass of red wine over dinner. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realismit's literally impossible to describe one's experiences to another person coherently in adverbial language — Count Timothy von Icarus

True, but then again it's literally impossible to describe one's subjective experiences to another person coherently using any language, in that how would it be possible to describe the experience of the colour red to someone who has never had the ability to see colour.

===============================================================================

Could an adverbial description do the same thing? — Count Timothy von Icarus

One advantage of an adverbial description is that it negates the homunculus problem.

===============================================================================

In general though, the adverbial view tends to apply adverbs only to the perceiver, e.g., to people "seeing greenly," but not to plants "reflecting light greenly." — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, because it is the perceiver who perceives things. If I perceive the colour green, it could have had numerous causes, a traffic light, grass, a plant, a bird, etc, My perception of the colour green will be identical even though it could have have multiple possible causes.

It is the nature of language to mix the literal with the figurative, in that "I perceive the colour green" is a figure of speech for the more literal "I perceive greenly". -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhich is like saying "one difference could be that bachelors exist and unmarried men don't". — Michael

Not really, as that statement is factually untrue. Both bachelors and unmarried men exist.

Why do you think that sense data exist? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSo if I'm wrong and there is a difference between sense data and qualia then what is that difference? — Michael

One difference could be that qualia exist and sense data don't. I directly know the "qualia" of the colour red, a sharp pain, an acrid smell, etc. But I don't know where my sense data are. Has any scientist discovered the site of sense data in the brain? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAs I understand it, sense data and qualia are the same thing. — Michael

Only if sense data exist. The Adverbialist doesn't need them. Why do you think sense data exist if they are not needed? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAccording to the SEP article adverbialists accept qualia. If sense data and qualia are the same thing then according to the SEP article adverbialists accept sense data. — Michael

The Adverbialist may accept qualia but don't need sense data. For the Adverbialist, qualia exist but sense data don't, so they cannot be the same thing.

From SEP article The Problem of Perception

Part of the point of adverbialism, as defended by Ducasse (1942) and Chisholm (1957) is to do justice to the phenomenology of experience whilst avoiding the dubious metaphysical commitments of the sense-datum theory. The only entities which the adverbialist needs to acknowledge are subjects of experience, experiences themselves, and ways these experiences are modified.

From Philosophy 575 Prof. Clare Batty on Adverbialism

1. Against the Sense Datum View

The adverbialist rejects the Phenomenal Principle, that if there sensibly appears to a subject to be something which possesses a particular sensible quality then there is something of which the subject is aware which does possess that quality.

According to the adverbialist, statements that appear to commit us to the existence of sense data can be reinterpreted so as to avoid those commitments. In doing so, the adverbialism rejects the act/object model of perceptual experience—the model on which sensory experience involves a particular act of sensing directed at an existent object (e.g., a sense datum). -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAdverbialist Indirect Realism seems the way to go.

I don't get the distinction between sense data and qualia. — Michael

The Adverbialist rejects sense data. Sense data should go the way of the aether, of historic interest only. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBut indirect realists generally say we experience pain "directly," — Count Timothy von Icarus

The Adverbialist Indirect Realist might say in general conversation "we experience pain directly", but only as a figure of speech, not in a literal sense.

For the Adverbialist, it is not that "I see white", but rather "I see whitely". It not that that "I feel pain", but rather "I feel painly".

John Searle's quote from The Philosophy of Perception and the Bad Argument develops this idea. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe term "Direct Realism" is misleading.

Direct Realism can refer to either a causal directness, aka Phenomenological Direct Realism or a cognitive directness, aka Semantic Direct Realism. I imagine today that most Direct Realists are Semantic Direct Realists, in that Phenomenological Direct Realism would be hard to justify.

There are two separate aspects to the word "Direct" in Direct Realism, linguistic and cognitive.

As regards linguistics, inferred knowledge cannot be direct knowledge.

For example, hearing a noise next door I can infer from knowing my neighbours holiday plans that my neighbours were the cause of the noise. I have no direct knowledge that they were the cause of the noise, as such knowledge was inferred.

As regards cognition, although a subsequent effect can be directly known from a prior cause, the prior cause of a subsequent effect cannot be known because there is a direction in the flow of information in a chain of events between cause and effect.

For example, if I hit a billiard ball on a billiard table, I can directly know its final resting position, but if I see a billiard ball at rest on a billiard table, it is impossible to know its prior position.

For the linguistic aspect, as inferred knowledge cannot be direct knowledge, the term "Direct Realism" is misleading.

For the cognitive aspect, as information cannot flow from a subsequent effect to a prior cause, the term "Direct Realism" is misleading. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAdverbialism replaces the Sense-Datum Theory

Within Indirect Realism is the Sense-Datum Theory and Adverbialism. Today, the Sense-Datum theory has generally been replaced in favour of Adverbialism, which rejects the Sense-Datum Theory.

Some of our knowledge is direct involving our senses. Such as seeing the colour red, smelling something acrid, feeling a sharp pain, tasting something sweet or hearing a grating noise.

Some of our knowledge is indirect. Such as the cause of seeing the colour red was a post-box, the cause of an acrid smell was a bonfire, the cause of the sharp pain was a bee sting, the cause of the sweet taste was an apple or the cause of the grating noise was a gate closing .

The words direct and indirect have value in language.

In language it is normal to say that "I feel a sharp pain". If taken literally, this suggests that the pain I feel is external to the I that is feeling it and leads to the homunculus problem. However, even the ordinary man knows that there is a difference between language that is literal and language that is figurative. Even the ordinary man knows that if I say to someone "I see that you have a bright future", they know they are not talking to a seer, but someone using the language figuratively. The expression "I feel a sharp pain" is figurative, not iteral.

John R Searle in The Philosophy of Perception and the Bad Argument makes the point that an expression such as "I feel a sharp pain" cannot be taken literally but only figuratively, when he wrote:

The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

This is why the Sense-Datum Theory has probably fallen out of favour to be replaced by Adverbialism. Adverbialism explicitly does not treat the pain I am feeling as external to the I that I am feeling it. Adverbialism avoids any homunculus infinite regress problem, where I perceive myself perceiving myself perceiving..................

Adverbialism does justice to the phenomenology of experience whilst avoiding the dubious metaphysical commitments of the sense-datum theory. (SEP - The Problem of Perception) -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWittgenstein was a major influence on adverbial theories. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist believe that we directly perceive a hand, and both are Adverbialists in the sense that what is being perceived cannot be separated from the process of perceiving. IE, if nothing was being perceived, then there would be no process of perceiving, in that what is being perceived is an intrinsic part of the process of perceiving.

The adverbialist view of Wittgenstein is more relevant to thoughts. Consider "I hope you come" or "I hope X". The traditional philosopher would say that "I hope" is a process and X is separate to "I hope". But Wittgenstein as an adverbialist would say that X is the manner in which one hopes, such as "I run quickly". (Wittgenstein on Understanding as a Mental State - Francis Y Lin)

Adverbialism is a form of Indirect Realism (SEP – Epistemological Problems of Perception).

===============================================================================

Since cause, matter, energy, and information appear to flow across this boundary in the same manner as any other, I am not sure how movement across the boundary is supposed to be more "indirect."...Is this logical necessity or causal? — Count Timothy von Icarus

On the world side of the boundary is the wavelength of 500nm and on the mind side of the boundary is the perception of the colour green.

I am sure that both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that the chain of events from the object in the world to the perception in the mind is direct, being determinate. However, there is no causal necessity as the chain of events could be broken at any moment.

Indirectness enters the picture because of inference. Inferences are made about a new situation using reasoning based on prior knowledge .

Toni never eats sushi, so I infer Toni doesn't like sushi. That man is running towards the bus, so I infer he wants to catch the bus. I see red dot in the night sky and from my knowledge of astronomy infer that it was caused by the planet Mars. As I know my neighbours moved in last week, I infer they are causing the noise.

In none of these real life cases does my inference lead to direct knowledge. I have no direct knowledge that Toni doesn't like sushi, or the man wants to catch the bus, or the red dot was caused by the planet Mars or my neighbours are making the noise. IE, there is no logical necessity that my inference leads to direct knowledge.

The Indirect Realist would say that they infer that the red dot has been caused by the planet Mars. The Direct Realist would say the red dot is the planet Mars, assuming a knowledge that they can never have.

===============================================================================

Is there any knowledge that doesn't involve inference?...We don't see various shapes and hues and then, through some concious inferential process decide that we have knowledge of a chair in front us. We just see chairs. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I perceive the colour red. This is a direct perception and doesn't involve inference as it is within my mind. Is this knowledge? Probably, as one Merriam Webster definition of "knowledge" is "the fact or condition of being aware of something".

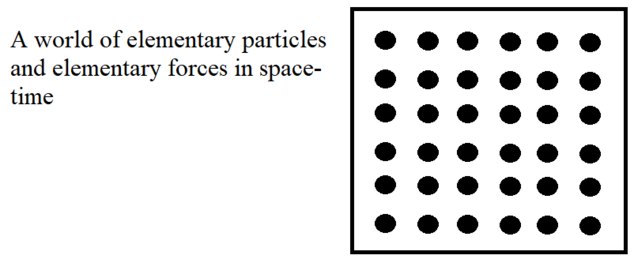

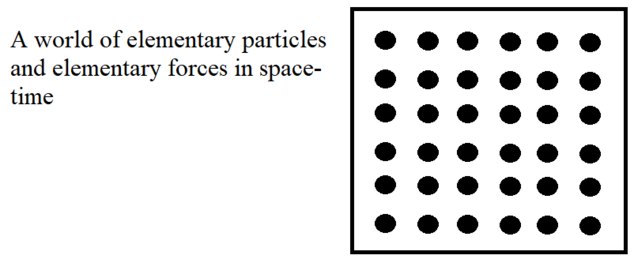

I go back to my diagram. Within the diagram we see dots, analogous to parts in the world. I agree that parts ontologically exist in the world as primitives, ignoring the exact nature of these parts.

The question is, do wholes ontologically exist in the world?

Within the diagram we may see the shape X, the shape L or the shape of a chair. Because we see the shape of an X, L or chair in the diagram, does it of necessity logically follow that the shapes X, L or chair must exist in the diagram independently of any observer?

As my belief is that relations have no ontological existence in the world, it follows that neither do I believe that wholes ontologically exist in the world.

We both may see a chair within the diagram. Why do you think that just because we both see the shape of a chair in the diagram, the shape of a chair must exist in the diagram independently of any observer? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIt's not that when we perceive a tree we perceive a concept but that when we perceive a tree we are "perceiving treely", which is a mental state. — Michael

Trying to understand adverbialism

I agree that saying "we perceive a tree" is problematic for the Indirect Realist as it leads into the infinite regress homunculus problem.

We say that an apple has the properties green, circular and sweet, but take away all the properties and nothing will remain, as pointed out by FH Bradley (SEP – Bradley's Regress). An apple don't exist as a Platonic Form independently of its properties.

Similarly, take away what is being perceived and there will be no perception. There must be an Intentionality, as Brentano argued, where thoughts must have a content (SEP - Intentionality)

It follows that it is not the case that we perceive a tree but rather the tree is the perception.

As the Adverbialists propose, we don't "perceive a tree" but rather "we perceive treely", where treely is an adverb qualifying the verb to perceive.

Therefore, rather than say "I perceive a tree", "I perceive a house" or "I perceive a cat", more accurate would be to say "the tree is the perception", "the house is the perception" or "the cat is the perception"

But if this is the case, then the Platonic Form of a perceiver seems to have disappeared, in that the perceiver is no more than a property of what is being perceived at that particular moment.

Perhaps the consequence of the Homunculus problem is that there is no single perceiver who is perceiving all these things but rather is just a property of whatever is being perceived at the time.

In summary, as concepts only exist as rules governing how it may be instantiated as concrete particulars, rather than writing "We perceive a tree. A tree is a concept. Therefore we perceive a concept" perhaps better would have been "A tree is the perception. A tree is an particular concrete instantiation of the concept of a tree. Therefore, a particular concrete instantiation of the concept of a tree is the perception". -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI'm asking if "There are Cypress trees lining the bank" states the way things are if and when there are Cypress trees lining the banks?..............I'd like to read your answer to the question above — creativesoul

I agree that the proposition in language "There are Cypress trees lining the bank" states the way things are if and when there are in the world Cypress trees lining the banks.

However, the question is, where exactly is this world. Does this world exist in the mind or outside the mind. It is interesting that Wittgenstein was always very careful never to give his opinion.

===============================================================================

Being conscious of perceiving requires language use. Otherwise, one merely perceives. One can be conscious of what they're perceiving, but one cannot be conscious of the fact that they are perceiving until and unless they have language use as a means to talk about that as a subject matter in its own right. — creativesoul

I could say "I perceive the colour green" or "I am conscious of the colour green". These mean the same thing, on the assumption that perceiving requires consciousness, in that I can only perceive something when conscious.

When I say "I am conscious that I perceive the colour green", this means that I am saying that my statement "I perceive the colour green" is a true statement in the event the listener thought I was uncertain about what I saw.

===============================================================================

You need not know that your belief is true in that case in order for it to be so. — creativesoul

When looking at the same object, I may perceive the colour green and the other person may perceive the colour blue. I can never know what colour they are perceiving, not being telepathic. However, if the other person is perceiving the colour blue, then one of us is not seeing the object as it really is.

===============================================================================

A capable creature need not know that they're seeing a Cypress tree in order to see one......................I'm making the point that to see the green apple as "a green apple" requires language use, whereas seeing the green apple does not. — creativesoul

This goes back to my diagram. Because the observer sees an X, does that mean there is an X, or are they imposing their private concept of an X onto what they see.

===============================================================================

We do not perceive mental concepts. — creativesoul

We perceive a tree. A tree is a concept. Therefore we perceive a concept.

===============================================================================

That looks like special pleading for elementary particles. What makes them different from Cypress trees? — creativesoul

As discussed within Ontic Structural Realism, elementary particles are primitive whereas trees are not. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIf "direct knowledge" is aphenomenal knowledge, it wouldn't seem to make sense as a concept. — Count Timothy von Icarus

There can be different types of phenomenal knowledge. For example, "what" it is like to experience pain, "that" Mars is 225 million km from Earth, "how" to ride a bicycle, etc.

We can think of our interaction with the world as two distinct stages, first perception, ie, knowledge "what", and second reasoning about these perceptions, ie, knowledge "that".

To my understanding the vast majority of Direct Realists are Semantic Direct Realists rather than Phenomenological Direct Realists, as Phenomenological Direct Realism would be very difficult to justify.

===============================================================================

So, humoncular regress concerns aside, — Count Timothy von Icarus

The homuncular argument is a straw-man argument deliberately conflating perception with reason. The Indirect Realist believes that we directly perceive a hand, then considers the philosophical question as to whether what we perceive is the hand itself or an image of the hand. The Direct Realist also believes that we directly perceive a hand, but then ignores any philosophical questioning in favour of the language of the "ordinary man".

===============================================================================

If brains and sense organs perceive, and they are part of the world, wherein lies the separation that makes the relationship between brains and the world indirect? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Even though the brain is part of the world, there is a distinct boundary between the brain and the world outside the brain. The brain only "knows" about the world outside the brain because of the information that passes through this boundary, ie, the five senses, and these five senses are the intermediary between the brain and the world outside the brain.

If outside the brain is a wavelength of 500nm, and inside the brain is the perception of green, even though the chain of events from outside to inside is direct, it does not of necessity follow that there is a direct relationship between what is on the outside and what is on the inside, and by linguistic convection, if the relationship is not direct then it must be indirect.

===============================================================================

If knowledge only exists phenomenally, calling phenomenal knowledge indirect would be like saying we only experience indirect pain, — Count Timothy von Icarus

STAGE ONE - PERCEPTION

The words direct and indirect are superfluous, so stage one doesn't distinguish Indirect and Direct Realism.

For example, suppose I perceive pain. I then have the phenomenal knowledge of "what" it is like to perceive pain. I agree that if I know pain, the word "directly" as in "I directly know pain" is redundant.

STAGE TWO - REASONING ABOUT THESE PERCEPTIONS

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that there is a direct causal chain from something in the world to our perception of this something in the world. So this doesn't distinguish Indirect from Direct Realism.

I assume that both the Indirect and Direct Realist would agree that given an existing knowledge base we can then reason from our perception and infer what has caused such perception. For example, when looking up at the night sky, and having some astronomical knowledge, when seeing a red dot we can reason that the cause of the red dot was in fact the planet Mars. Therefore this doesn't distinguish the Indirect from Direct Realist

IE, given an existing knowledge base and using reasoning we can infer the cause of our perceptions.

The question then becomes, which is more grammatical, as the Indirect Realist would say ""we have indirect knowledge of the cause of our perception" or as the Direct Realist would say "we have direct knowledge of the cause of our perception".

My belief is that to say that inferred knowledge is direct knowledge is ungrammatical.

For example, suppose I am in a closed room and hear a knocking on the wall. From my prior knowledge base of rooms and people, and using my reason, I may infer that the cause of the noise was in fact a person in the next room. Because my belief that the cause was someone in the next room is only an inference, I cannot say that I have any direct knowledge that there is a person next door.

Similarly, suppose I look at the night sky and see a red dot. From my prior knowledge of astronomy, and using my reason, I may infer that the cause of my perception was the planet Mars. Because my belief that the cause was the planet Mars is only an inference, I cannot say that I have any direct knowledge that the cause was the planet Mars.

In summary, it is ungrammatical to say that inferred knowledge is direct knowledge as the Direct Realists propose. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe idea is that there is some alternative vantage point which is more fundamental than phenomenal experience, and which makes inferences based on the phenomenal experience. — Leontiskos

For the Indirect Realist, inferences about the world are made based on phenomenal experiences, in that I see a red dot and infer that it was caused by the planet Mars.

For the Direct Realist also, when seeing a red dot, the inference is made that it was caused by the planet Mars.

For both the Indirect and Direct Realist, the world can only be inferred from their phenomenal experiences.

In what sense is inferred knowledge direct knowledge? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismBut of course the noumenal isn't actually said to to only act/exist in-itself, it's said to act on us, to cause. So we know it through its acts, but then this is said to not be true knowledge. How so? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, on the one hand, the thing-in-itself can be quite unknowable, even though what it does can be quite knowable.

I look at an object and perceive the colour green. Something about the object has caused me to perceive the colour green.

Humans often conflate cause with effect, in that if a green object is perceived, the cause is described as a green object.

Knowledge is about what I perceive, the appearance, the phenomena, not what has caused such a perception, the unknowable thing-in-itself.

===============================================================================

There has to be a way to distinguish between fantasy and fiction, between Narnia and Canada. So, to simply say that dragons and gorillas both come from mind is to miss something that differentiates them. — Count Timothy von Icarus

For the Neutral Monist, in the mind-independent world, the dragon has the same ontological existence as the gorilla, ie, none. For the Neutral Monist, dragons and gorillas are concepts that only exist in the human mind.

We impose our concepts onto what we observe in the world, and if there is a correspondence between our concept and what we observe in the world, we say that the subject of the concept exists in the world.

Therefore, we define fantasy as a concept that we have not yet observed to exist in the world and fact as a concept that we have observed to exist in the world.

However, the fact that we have never observed a dragon in the world is not proof that dragons don't exist in the world, it's only proof that we have never observed one.

===============================================================================

Is the claim that something only has "ontological existence" if it is "mind independent?" Wouldn't everything that exists have ontological existence? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, even though the thought of beauty only exists in the mind, the fact that the thought exists means that is has an ontological existence. The exact nature of its ontological existence is as of today a mystery.

Within the world, part is mind and part mind-independent. It may well be that panprotopsychism is correct, and the part that is mind is no different to the part that is mind-independent. In this event, separating the world into mind and mind-independent is just a linguistic convenience.

===============================================================================

So the concept cat only has to do with humans and nothing outside them? I just don't find this plausible. This would seem to lead to an all encompassing anti-realism. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Each life form having a mind, whether human or cat, can only have direct knowledge of what is in its own mind, though can presumably reason about what it has perceived

This is compatible with Anti-Realism, where an external reality is reasoned about rather than being directly known about.

From the Wikipedia article on Anti-realism

In anti-realism, the truth of a statement rests on its demonstrability through internal logic mechanisms, such as the context principle or intuitionistic logic, in direct opposition to the realist notion that the truth of a statement rests on its correspondence to an external, independent reality. In anti-realism, this external reality is hypothetical and is not assumed.

As life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years, I am sure that as humans have the concept of cats, cats also have the concept of cats. I believe that cats have the concept of cats, but I don't know, as I have no telepathic ability. But then again, I don't know that other people have the same concept of cats as I do for the same problem of telepathy.

The notion of cat can refer to either the word "cat" or the concept cat. If referring to the word "cat" then this is specific to English speakers, but if referring to the concept cat, then this may be common across different languages and different life forms

However, this raises the problem of the indeterminacy of translation, in that "cat" in English may not mean the same as "chat" in French.

From the IEP article The Indeterminacy of Translation and Radical Interpretation

It is true that, in the case of translation too, we have the problem of underdetermination since the translation of the native’s sentences is underdetermined by all possible observations of the native’s verbal behaviour so that there will always remain rival translations which are compatible with such a set of evidence.

It also raises the problem as how a cat knows the concept of cat without a language having the word "cat" as part of it, taking us back to Wittgenstein's Private language problem.

===============================================================================

Wittgenstein pointed out that if language is defined as something used to communicate between two or more people, then, by that definition, you can't have a language that is, in principle, impossible to communicate to other people. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't think Wittgenstein's Private Language Argument was about definitions

Wittgenstein argued that a Private Language is impossible

From the SEP article Private Language

In §243 of his book Philosophical Investigations explained it thus: “The words of this language are to refer to what only the speaker can know — to his immediate private sensations. So another person cannot understand the language.” ............Wittgenstein goes on to argue that there cannot be such a language. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI find that mereological nihilism (i.e. the denial that wholes like trees and cats really exist) tends to have two problems. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't see your two problems as problems, more part of the road to a solution.

===============================================================================

There is plenty of work in the philosophy of physics and physics proper that claims to demonstrate that "particles" are just another of those things that don't really exist "independently of humans." They are a contrivance to help us think of things in the terms we are used to. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree. My understanding at the moment is that the true nature of a mind-independent world consists of fundamental particles and fundamental forces in space-time. But that said, I haven't the foggiest idea about the true nature of fundamental particles, fundamental forces, space and time.

However, given a choice, I find it more likely that the true nature of a mind-independent world is more like fundamental particles, fundamental forces in space-time than trees, apples, beauty, governments, chairs and tables.

===============================================================================

mathematized conceptions of the universe, ontic structural realism, tends to propose that the universe as a whole is a single sort of mathematical object......................Everything seems to interact with everything else — Count Timothy von Icarus

Accepting that there are different versions of Ontic Structural Realism, I agree that the idea that objects, properties and relations are primitive have been undermined by science.

===============================================================================

How do we resolve the apparent multiplicity of being with its equally apparent unity? — Count Timothy von Icarus

In Kant's terms, the transcendental unity of apperception, a feature of the mind rather than a feature of things-in-themselves.

===============================================================================

Where exactly do you see the trees, cats, and thunderstorms as coming from? — Count Timothy von Icarus

From the same place that beauty, ghosts, bent sticks and unicorns come from, from the mind.

===============================================================================

But this presents a puzzle for me. If the experience of trees is caused by this unity, then it would seem like the tree has to, in some way, prexist the experience. Where does it prexist the experience? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, the concept of a "tree" pre-exists not only my experience of a tree but also pre-exists my existence.

Prior to my existence, the concept of "tree" was stored partly in writing and partly in the minds of the users of the language.

If I didn't have the concept of a "tree" prior to looking at the world, I wouldn't know when I was looking at a tree.

===============================================================================

1. It doesn't really make sense to declare that "human independent" being is more or less real. — Count Timothy von Icarus

If I am stung by a wasp, I could say "my pain is real". As an adjective, "my pain is real" means I am being truthful when I say that "I am pain". As a noun "my pain is real" is more metaphysical, in that in what sense does pain exist. It cannot have an ontological existence in a mind-independent world, but can only exist as part of a mind.

I could say "100 million years ago the Earth was real". As an adjective, this means I am being truthful when I say "the Earth was real". As a noun, "the Earth was real" is more metaphysical, in that in what sense was the earth real.

As with "my pain is real", where "real" is being used as a noun, my belief is that the "Earth was real" doesn't refer to an ontological existence in a mind-independent world, but rather refers to an idea in the mind.

===============================================================================

2. Notions like tree, cat, tornado, etc. would seem to unfold throughout the history of being and life, having an etiology that transcends to mind/world boundary — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree that notions like tree, cat, tornado, etc unfold throughout the history of English speakers, presumably all human, but not throughout the history of non-English speakers, nor other forms of life, such as cats and elephants.

As Wittgenstein pointed out, the possibility of a private language is remote, and that all language is a social thing requiring an individual speaker to be in contact with other users of the language.

For me, part of my world is other people and the language they use. These words, tree, cat, tornado, cannot exist solely in my mind as a private language, but must transcend the boundary between my mind and my world.

However, although these words do transcend the boundary between my mind and my world, this does not mean that they transcend the boundary between the mind and a mind-independent world.

===============================================================================

3. Self-conscious reflection on notions, knowing how a notion is known, and how it has developed, would be the full elucidation of that notion, rather than a view where the notion is somehow located solely in a "mind-independent" realm, which as you note, has serious plausibility problems — Count Timothy von Icarus

The notion of a tree to an Icelander is presumably different to the notion of a tree to a Ghanaian, though they probable agree that a tree is "a woody perennial plant having a single usually elongate main stem generally with few or no branches on its lower part" (Merriam Webster)

Everyone, because of their different life experiences, educations, professions, childhoods and lifestyles, most probably has a different concept of what a "tree" is. Though even though their particular concepts may be very different, this wouldn't stop them having a sensible conversation about trees.

I would hazard a guess that no two people on planet Earth thinks of a "Tree" in exactly the same way, meaning that no-one on planet Earth can know a "tree" as it is. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismSeeing the color green as "green" is what we do after talking about it. — creativesoul

Exactly, it is a question of linguistics.

As an Indirect Realist, I can say "I can see a green object", and everyone knows exactly what I mean. Even the ordinary man in the street knows what I mean.

The ordinary man knows exactly what I mean, because even the ordinary man knows what a figure of speech is.

If I said to the ordinary man "I see that your future is looking bright", even the ordinary man wouldn't assume that they were talking to a seer having supernatural insight. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWould you say something of the object makes it appear green, or makes you perceive it as being green, or makes it reflect that wavelength, for instance chlorophyll? — NOS4A2

Yes, there is something distinctive about the object that means it absorbs some wavelengths of light and reflects the rest, making the object appear green to an observer.

In a similar way, the fact that a mirror appears to be a person does not mean that the mirror is a person. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou can contrast the object with other objects of similar or dissimilar colors. So it’s clear to me that something of that object makes it green. What makes it not green, in your view? — NOS4A2

I would say that I perceive an object as being green.

If I perceive an object as being green, then only as a figure of speech I would say that the object is green.

I might say that the object has reflected light of a wavelength of 500nm which I perceive as being green.

I would never say that the object is green in an ontological sense.

The object is not green in the same way that the mirror is not a person. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWe know the object is green because that’s what it looks like. — NOS4A2

Sunlight hits an object in the world, some light is absorbed by the object and what light isn't absorbed is reflected off the object, this light travels through space to the eye, enters the eye and travels up the optic nerve as an electrical signal to the brain where it is somehow processed by the brain enabling the mind to perceive a green colour.

When you look into a mirror and see the reflection of a person, you wouldn't say that the mirror is a person.

So why, when you look at an object that has reflected a wavelength of 500nm, do you say that the object is green?

What do you mean by the word "is", as in "the object is green"? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismCollections of atoms exist independently of us, but that this collection of atoms is a car is not independent of us. — Michael

Agree. There is also the problem of relations. If a set of parts makes a whole, and a collection of atoms makes a car, then there must be some kind of ontological relation between the parts and the whole and there must be some kind of ontological relation between the collection of atoms and the car. Ontological relations are problematic. (As an aside, relations between objects has a different meaning to forces between objects.)

But as the SEP article on Relations writes:

Some philosophers are wary of admitting relations because they are difficult to locate. Glasgow is west of Edinburgh. This tells us something about the locations of these two cities. But where is the relation that holds between them in virtue of which Glasgow is west of Edinburgh? The relation can’t be in one city at the expense of the other, nor in each of them taken separately, since then we lose sight of the fact that the relation holds between them (McTaggart 1920: §80). Rather the relation must somehow share the divided locations of Glasgow and Edinburgh without itself being divided.

As the SEP article on Bradley's Regress writes

“Bradley’s Regress” is an umbrella term for a family of arguments that lie at the heart of the ontological debate concerning properties and relations. The original arguments were articulated by the British idealist philosopher F. H. Bradley, who, in his work Appearance and Reality (1893), outlined three distinct regress arguments against the relational unity of properties. Bradley argued that a particular thing (a lump of sugar) is nothing more than a bundle of qualities (whiteness, sweetness, and hardness) unified into a cohesive whole via a relation of some sort. But relations, for Bradley, were deeply problematic. Conceived as “independent” from their relata, they would themselves need further relations to relate them to the original relata, and so on ad infinitum. Conceived as “internal” to their relata, they would not relate qualities at all, and would also need further relations to relate them to qualities. From this, Bradley concluded that a relational unity of qualities is unattainable and, more generally, that relations are incoherent and should not be thought of as real.

If relations have no ontological existence in the world, then in a mind-independent world there can only ever be a collection of parts and never any whole. There can be elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time, but there can never be trees. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismYou cannot believe that the Cypress trees along the banks of Mississippi delta backwaters only exist within your mind. — creativesoul

In a world independent of humans are elementary particles, elementary forces in space-time. When we look at such a world, we directly see the world as it is.

The human has various concepts, including the letter "X", and can impose their concept of "X" onto what they see in the world, thereby enabling them to see an X in the world. Because we can see the letter X in the diagram above, does that mean the letter X exists in the diagram above.

I agree that the parts making up what we call X can exist independently of humans.

The question is, can what we call X exist as a whole exist independently of humans.

My belief is that whilst the parts making up what we call X can exist independently of humans, what we call X as a whole can only exist in the presence of humans.

The human can look at the world and see a tree. I would agree that the parts making of what we call a tree can exist independently of humans, but wouldn't agree that what we call a tree can exist as a whole independently of humans. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe question is whether or not - during the all times when we are looking at Cypress trees lining the banks - if we are directly perceiving the world as it is — creativesoul

You can only know that you are looking a a mkondo in the world if you already know the meaning of "mkondo". It is true that humans may impose their concept of a "mkondo" onto the elementary particles and elementary forces that they observe in space-time, but this mkondo wouldn't exist without a human concept being imposed upon the elementary particles and elementary forces that do exist in space-time.

So what are we perceiving?

On the one hand we are perceiving a set of elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time, meaning that we are directly perceiving the world as it is, and on the other hand we are also perceiving a mental concept, meaning that we are also indirectly perceiving the world as we think it is.

Perception needs both aspects, something in the world and something in the mind.

===============================================================================

You figure the tree stops being a directly perceptible entity that has existed long before you ever came across it simply because you've never seen one? — creativesoul

As a "tree" is a human concept, and as human concepts didn't exist prior to humans, then "trees" couldn't have existed priori to humans. It is true that humans may impose their concept of a "tree" onto the elementary particles and elementary forces that they observe in space-time, but this tree wouldn't exist without a human concept being imposed upon it.

===============================================================================

You cannot believe that the Cypress trees along the banks of Mississippi delta backwaters only exist within your mind. — creativesoul

Speaking from a position of Realism, I agree that something exists in the world independent of any human observer, such as elementary forces and elementary particles in space-time. However, as "cypress trees along the banks of Mississippi delta backwaters" only exist as human concepts, they can only exist in the human mind. It is true that I may impose my concept of a "tree" onto what I observe in the world, but the tree as a single entity still only exists in my mind and not the world. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI'm asking if "There are Cypress trees lining the bank" states the way things are if and when there are Cypress trees lining the banks? — creativesoul

I think it is right as you have done to distinguish words within exclamation marks to refer to thoughts and language and words not in exclamation marks to refer to things in the world.

===============================================================================

You and I are most certainly working from very different notions of "mind" and "perception". — creativesoul

Possibly. For example, I would say that "I am conscious of seeing the colour green", "I am conscious of tasting something bitter", "I am conscious of an acrid smell", "I am conscious of a sharp pain" or "I am conscious of hearing a grating noise".

Therefore, in my mind I am conscious of perceiving a sight, a taste, a smell, a touch or a hearing.

===============================================================================

You've always held false belief then. It is sometimes possible — creativesoul

I wrote that I can never know what someone else is thinking. However, sometimes I can guess. Though, I can never know whether my guess is correct or not.

===============================================================================

We need not know the meaning of "trees lining the banks" in order to see trees lining the banks. — creativesoul

You look at the world. Do you see a mkondo?

You obviously cannot know whether you are seeing a mkondo or not until you know the meaning of "mkondo".

IE, you have to know the meaning of "trees lining the banks" before knowing whether you can see trees lining the banks. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismMany millennia of being embedded in the world have granted sapiens in particular, and biological sight in general, the ability to receive information from their surroundings, including color. It is because organisms have been in the world and directly interacted with it this whole time that has allowed them to do so. I wager that had perception been at any time indirect, the evolution of perception would not have occurred at all and we’d still possess the perceptual abilities of some Cambrian worm. — NOS4A2

I agree that humans have evolved in synergy with the world over millions of years, and have evolved to survive within this world.

Successful evolution requires that there is a direct causal chain between an event in the world and the human's perception of it, and that this direct causal chain is consistent, in that every time an object in the world emits a wavelength of 500nm the human perceives the colour green. Evolution would fail if when an object emitted a wavelength of 500nm, one time the human perceived the colour green, the next time the colour purple and the next time nothing at all.

However, for the Indirect Realist, what is indirect is the relation between the object that exists in the world and the observer's perception of it.

As I see it, the Direct Realist is proposing that we know the world as it really is, in that if we perceive an object to be green then we know that the object is green.

I don't think that this is a case of semantics for the Direct Realist, in that if we perceive an object to be green then by definition the object is green. I think that the Direct Realist is saying that the object "is" ontologically in fact green.

The Indirect Realist is proposing that we don't know the world as it really is, but only know a representation of it, in that our perception of the colour green is only a representation of the object..

The question for the Direct Realist is, how can they know that the object is really green if their only knowledge of the object has come second-hand through the process of a chain of events, albeit a direct chain of events. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismOne of the central flaws in Kant’s theory of knowledge is that he has blown up the bridge of action by which real beings manifest their natures to our cognitive receiving sets. He admits that things in themselves act on us, on our senses; but he insists that such action reveals nothing intelligible about these beings, nothing about their natures in themselves, only an unordered, unstructured sense manifold that we have to order and structure from within ourselves. But action that is completely indeterminate, that reveals nothing meaningful about the agent from which it comes, is incoherent, not really action at all. (W. Norris Clarke) — Count Timothy von Icarus

I go into the garden and am stung. I have no idea what the cause was. It could have been a bee, wasp, hornet, mosquito, flea, spider, cactus, algarve, yucca, pampas grass, holly, thorn bush, pyracantha, rose, gorse, etc.

And yet the implications could be serious. A swelling, going to the medicine cabinet, taking antibiotics, using antiseptic cream, even having to go to A&E and a possible night in hospital.

For Norris Clarke to argue that Kant's theory of knowledge is flawed because "action that is completely indeterminate, that reveals nothing meaningful about the agent from which it comes, is incoherent" is not persuasive.

The cause of the sting may well be completely indeterminate, the thing in itself may remain forever unknown and I may never know anything meaningful about the agent, but this is irrelevant to the real world consequences of being stung.

As Kant writes, what concerns us is what we perceive, not an unknown cause of what we perceive. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAre the trees lining the banks not bald cypress? — creativesoul

Because you have the concept of a bald cypress before looking at the river bank, you perceive a bald cypress.

As I don't have the concept of a bald cypress, all I perceive is a mass of green with some yellow bits.

Did the bald cypress exist before anyone looked at it? You know that a mass of green with some yellow bits is a bald cypress, but I don't know that

So how can a bald cypress exist in the world independently of any mind to observe it, if the bald cypress only exists as a concept in the mind? -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAre the trees lining the banks not bald cypress?... Are those things in our mind? I would not think a direct realist would arrive at that. — creativesoul

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist must agree that the thought of "trees lining the banks" must be in the mind, otherwise how would the mind know about trees lining the bank in the first place.

Both the Indirect and Direct Realist agree that there is something in the world causing us to perceive "trees lining the bank", as both believe in Realism.

The Indirect and Direct Realist differ in what the something is in the world that is causing us to perceive "trees lining the bank".

For the Direct Realist, in the world are trees lining the bank regardless of there being anyone to observe them, in that, if you look at the world you will perceive exactly the same thing as me. This means that if we are both looking at the same trees lining the bank, we will both be perceiving the same thing. This means that I will know what's in your mind at that moment in time.

For the Indirect Realist, in the world is something regardless of there being anyone to observe it. As what I perceive is a subjective representation of the something in the world, we may not be perceiving the same thing. This means that I cannot know what is in your mind when looking at the same thing.

As I have never believed it possible to know what someone else is thinking, I am an Indirect rather than Direct Realist. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI think the implication is that if you can take a thought and ferry it through the air to cause a thought in the other person, this constitutes telepathy. — AmadeusD

Whence the need for omniscience? — creativesoul

I didn't say this is telepathy, only that it "could be described as a form of telepathy".

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines telepathy as " communication from one mind to another by extrasensory means"

I am only referring to looking at the world, not inner feelings like pain.

The implication of Direct Realism is that if person A looks at the world they will be seeing the world as it really is, and if person B looks at the same world they would also be seeing the world as it really is. As there is only one world, each person would know what was in the other person's mind.

There is a causal chain from the world to the mind of person A through their senses, and there is a different causal chain from the same world to the mind of person B through their senses.

On the one hand there is no causal chain from the mind of person A to the mind of person B, yet the Direct Realist's position is that person A must know what is in person B's mind.

Call it a form of telepathy, communication by extrasensory means or transcendental knowledge, either way, it's a problem the Indirect Realist doesn't have. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI’m not sure how something can in fact be orange but appears blue, so I cannot suppose it. — NOS4A2

One possibility would be colour blindness. I'm sure you can think of others.

Colour vision deficiency (colour blindness) is where you see colours differently to most people, and have difficulty telling colours apart. There's no treatment for colour vision deficiency that runs in families, but people usually adapt to living with it. (www.nhs.uk/) -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismHow do you know that it is in fact orange if you never see the orange? — jkop

Obviously you cannot. That's why I wrote: "suppose the thing in the world is in fact orange, yet I always perceive it to be blue." -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismA recurring theme is that one can never experience a thing as it is due to this distance and the things in between one and the other...To say we do not perceive light, for instance, which is of the world, cannot be maintained, especially given how intimate this relationship is — NOS4A2

On the one hand, the Indirect Realist proposes that we can never experience a thing in the world as it is, meaning that the relationship between perceiver and thing in the world as it is is indirect. But on the other hand, the Indirect Realist also proposes that we do experience a thing in the world as we perceive it to be, meaning that the relationship between perceiver and thing in the world as the perceiver perceives it to be is direct.

The intimate relation between the perceiver and perceived is maintained.

IE, suppose the thing in the world is in fact orange, yet I always perceive it to be blue. It is true that I can never experience the thing in the world as it is, but this is irrelevant to my relationship with the world, as I always perceive the thing in the world to be as I perceive it to be, in this case, blue.

Wittgenstein makes the same point in Philosophical Investigations 293 with the beetle in the box analogy. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThat'll be the article which ends: The question, now, is not so much whether to be a direct realist, but how to be one. — Banno

The quote above from the SEP article The Problem of Perception refers to the debate within Direct Realism, not to the debate between Direct and Indirect Realism.

The paragraph in full is:

Whilst the debate between sense-datum theorists and adverbialists (and between these and other theories) is not as prominent as it once was, the debate between intentionalists and naive realist disjunctivists is a significant ongoing debate in the philosophy of perception: a legacy of the Problem of Perception that is arguably “the greatest chasm” in the philosophy of perception (Crane (2006)). The question, now, is not so much whether to be a direct realist, but how to be one. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAccording to the SEP article The Problem of Perception

Direct Realist Presentation: perceptual experiences are direct perceptual presentations of ordinary objects.

If person A directly saw an object as it really is, and person B looking at the same object also saw the object as it really is, then person A would know what was in person's B mind. This would be a consequence of Direct Realism and could be described as a form of telepathy. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhy in the world do you think direct realists think that? — flannel jesus

They are using their own particular language game, sui generis, where "direct" in the language game of the Direct Realist means "indirect" in the language game of the Indirect Realist. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismHow are we to know which parts of our experience provide us with “raw” information about the external world? — Michael

As the Indirect Realist would say, "exactly".

Everyone seems to agree that there is a chain of events. For example, light from the sun hits an object, part of the light is absorbed by the object and part reflected, a wavelength of 480nm then travels though space to the eye of an observer, this causes an electrical signal to travel along the optic nerve from the eye to the brain where it is somehow processed, thereby enabling the mind to perceive the colour blue.

Both the Indirect Realist and Direct Realist would agree that there has been a "direct" causal chain from the prior cause to the subsequent effect.

It then comes down to a semantic problem. What is it the correct use of language.

It cannot be that the observer has "direct" knowledge of the cause of their perception, as the cause is of a very different kind to the effect, and there is no information within the subsequent effect as to its exact prior cause. Whilst one prior cause determines one subsequent effect, one subsequent effect could have had numerous possible prior causes. There is a temporal direction of information flow. Consider the impossibility of looking at a billiard ball at rest on a billiard table and being able to determine its prior position just from knowledge of its rest position. The same with perceiving the colour blue.

It must be more grammatical to say that the subsequent effect, perceiving the colour blue, only gives us "indirect" knowledge of any prior cause.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum