Comments

-

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts................My suspicion is that your account is based on considering only one type of analytic statement.. — Banno

Your example may be reworded as: "a triangle is a plane figure, a polygon, where the sum of the internal angles is 180 deg", thereby defining "a triangle".

This is a complex concept, so can be carried out in a straightforward Performative Act of Naming, where one word is defined as a set of other words. This is a purely linguistic process, not requiring any link from word to world, and not requiring any link from linguistic to extralinguistic.

Where do "Gavagai", the inscrutability of reference and the indeterminacy of translation fit in this account? — Banno

The gavagai problem may be solved by taking into account the fact that there are simple and complex concepts, and these must be treated differently. In language, first there is the naming of simple concepts, and only then can complex concepts be named, such as the complex concept "gavagai".

Simple concepts include things such as the colour red, a bitter taste, a straight line, etc, and complex concepts include things such as mountains, despair, houses, governments, etc.

For complex concepts, the "gavagai" may be named in a Performative Act of Naming, such that "a gavagai is a gregarious burrowing plant-eating mammal, with long ears, long hind legs, and a short tail". One word is linked to other words, the linguistic is linked with the linguistic, not the world. Misunderstanding and doubt are minimised in a relatively simple process. As "a gavagai" is defined as having long ears, the statement "a gavagai has long ears" is analytic.

For simple concepts, the process is more complicated. The problem is that of linking a word to something in the world, linking the linguistic with the extra-linguistic. For example the colour "orange" is something that is orange, where one word is linked with one thing in the world

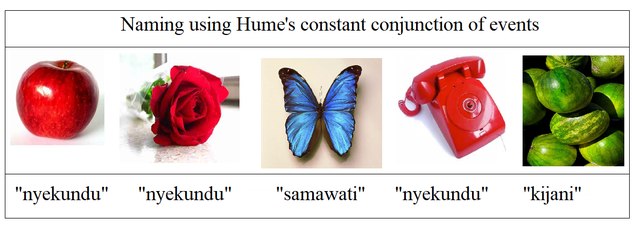

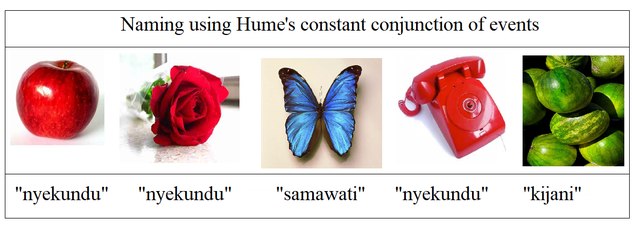

In order to explain the naming of simple concepts, I return to my diagram illustrating naming using Hume's constant conjunction of events, whereby learning a name is more an iterative process that is unlikely to be achieved at the first attempt. One needs to note that from the viewpoint of the observer, both the words and pictures are objects, things existing in the world, where the word is no less an object than the picture.

The words "nyekundu", "kijani" and "samawati" have been determined during Performative Acts of Naming either by an Institution or users of the language or a combination of both.

You asked before why the observer should necessarily link two objects that happen to be alongside each other. As the tortoise said to Achilles when playing chess, where is the rule that I have to follow the rules. Why should the observer take note of a constant conjunction of events? Because, as life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years on Earth, taking note of a constant conjunction of events has been built into the structure of the brain as a mechanism necessary for survival, something innate and a priori.

Chomsky proposed that a person's ability to use language is innate. Taken from the https://englopedia.com article Innateness theory of language:

Linguistic nativism is a theory that people are born with the knowledge of a language: they acquire language not only through learning. Human language is complex and considered one of the most difficult areas of human cognition. However, despite the complexity of the language, children can accurately learn the language in a short period of time. Moreover, research has shown that language acquisition by children (including the blind and deaf) occurs at ordered developmental stages. This highlights the possibility that humans have an innate ability to acquire language. According to Noam Chomsky, “the speed and accuracy of vocabulary acquisition do not leave any real alternative to the conclusion that the child somehow possesses the concepts available before the language experience, and basically memorizes the labels for the concepts that are already part of him or her. conceptual apparatus “

In summary, first, complex concepts may be learnt as a set of simpler concepts in a Performative act of Naming, linking the linguistic to the linguistic. Second, simple concepts may be learnt by linking two objects in the world using Hume's constant conjunction of events, an innate ability having evolved over 3.7 billion years. The first object a name established during a Performative Act and the second object a picture, thereby linking the linguistic with the extralinguistic. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsCan you explain Quine's objection to analyticity? — Banno

Quine wanted to give a non-circular account of the distinction between analytic and synthetic sentences.

Circular in that the notion of analyticity is being used as an explanation for necessity and a prioricity, yet necessity and a prioiricity is being used as an explanation of analyticity.

It is often said that analytic truths are true by definition, but Quine pointed out that an analytic truth can only be turned into a logical truth by replacing synonym with synonym, which again leads into the problem of circularity. Synonymity between two expressions leads to analyticity, but synonymity between two expressions requires analyticity.

As Quine wrote:

“There are those who find it soothing to say that the analytic statements of the second class reduce to those of the first class, the logical truths, by definition: ‘bachelor’, for example, is defined as ‘unmarried man.’ . . . Who defined it thus, and when? Are we to appeal to the nearest dictionary ...? Clearly, this would be to put the cart before the horse. The lexicographer is an empirical scientist, whose business is the recording to antecedent facts; and if he glosses ‘bachelor’ as ‘unmarried man’ it is because of his belief that there is a relation of synonymy between those forms . . . prior to his own work.”

Quine asks "who defined it thus", and the answer is, in a Performative Act, carried out either by a public Institution, by the general users of a language or a combination of the two.

J. L. Austin in the 1950's gave the name performative utterances to situations where saying something was doing something, rather than simply reporting on or describing reality. The paradigmatic case here is speaking the words "I do".

Kripke in Naming and Necessity provided a rough outline of his causal theory of reference for names, promoting it as having more potential that Russell's Descriptive Theory of Names, whereby names are in fact disguised definite descriptions. Kripke argues that your use of a name is caused by the naming of a thing, for example, the parents of a newborn baby name it, pointing to the child and saying "we'll call her 'Jane'." Henceforth everyone calls her 'Jane'. This is referred to as Jane's dubbing, naming, or initial baptism.

From the SEP - The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction:

“Analytic” sentences, such as “Paediatricians are doctors,” have historically been characterized as ones that are true by virtue of the meanings of their words alone and/or can be known to be so solely by knowing those meanings.

We can consider two stages in linguistic meaning:

Stage one: words are given their meaning in performative acts

Stage two: once words have their meanings, some statements are known to be true just by knowing the meaning of their words, ie, as the SEP notes, analytic statements.

The Performative Act breaks Quine's problem of circularity. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsIsn't this generally tautological? All unmarried men are bachelors is saying unmarried men are unmarried men. — Tom Storm

In the statement "bachelors are unmarried men", "bachelors" should be thought of as a definition rather than a description.

As a description "bachelors are unmarried men" is tautological, where "unmarried men" is a synonym for "bachelors".

But rather, "bachelor" should be thought of as a definition, where "bachelor" is the definition of "unmarried men".

For example, rather than say "I see a large building, typically of the medieval period, fortified against attack with thick walls, battlements, towers, and in many cases a moat", it is far more convenient just to say "I see a castle", where "castle" is the definition of a large building, typically of the medieval period, fortified against attack with thick walls, battlements, towers, and in many cases a moat.

Similarly, rather than say "I see an unmarried man", it is more convenient just to say "I see a bachelor".

If language only consisted of words that referred to simpler concepts: red, loud, circle, line, sweet, thick, etc, the number of words required to express complex concepts would be inconveniently excessive. Therefore, for convenience, definitions are used to group sets of words together. Without definitions, language would be unwieldy.

As "castle" is a definition, the statement "The castle has thick walls" is analytic. As "bachelor" is a definition, the statement "The bachelor is a man" is analytic. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsI think Chomsky (or at least some nativists) might argue that the very ability of the performative act is some sort of innate language acquisition capability. — schopenhauer1

I agree. Whilst on the one hand there cannot be a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act, on the other hand, there must be some innate, a priori knowledge of the importance of the concept of triangle, otherwise the language speaker wouldn't have considered it worthwhile naming.

As with "snow is white" is true IFF snow is white, the expression in inverted commas exists in language whilst the expression not in inverted commas exists in the world, there is a difference between "the triangle" which exists in language and the triangle which exists in the world.

It can be argued exactly where this world exists, in the mind or external to any mind. Wittgenstein in Tractatus avoided the question altogether.

Life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years on Earth, and must be responsible for the physical structure of the human brain as it is today, ie, the hardware. What the brain is capable of doing, ie it software, can only be a function of its hardware, ie, the physical structure of the brain. It is clear that a kettle can only boil water, it cannot play music, ie, what a physical structure is able to do must be determined by its physical structure, What the brain is able to achieve, its thoughts, concepts and language cannot be outwith the physical structure that enables such thoughts, concepts and language.

The linguist Noam Chomsky and the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould proposed the theory that language evolved as a result of other evolutionary processes, essentially making it a by-product of evolution and not a specific adaptation. The idea that language was a spandrel, a term coined by Gould, flew in the face of natural selection. In fact, Gould and Chomsky pose the theory that many human behaviours are spandrels. These various spandrels came about because of a process Darwin called "pre-adaptation," which is now known as exaptation. This is the idea that a species uses an adaptation for a purpose other than what it was initially meant for. One example is the theory that bird feathers were an adaptation for keeping the bird warm, and were only later used for flying. Chomsky and Gould hypothesize that language may have evolved simply because the physical structure of the brain evolved, or because cognitive structures that were used for things like tool making or rule learning were also good for complex communication. This falls in line with the theory that as our brains became larger, our cognitive functions increased.

As regards the immediate topic "Are there analytic statements?", as "the triangle" has been baptised in a performative act as meaning "a shape having three sides", the statement "the triangle has three sides" can only be analytic. Therefore, there are analytic statements. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan LinguisticsObviously there's a use-mention distinction, but is that distinction relevant here? — Michael

The problem is temporal.

Before the performative act, the combination of letters "the triangle" has no meaning.

As "the triangle" doesn't refer to anything, it has no use.

As "the triangle " doesn't exist in the common language, there cannot be any mention of it.

As "the triangle" doesn't exist in the common language, it cannot play a role in any analytic or synthetic statement.

During the performative act, the combination of letters "the triangle" is christened as a word, or as Kripke said, baptised, to have the meaning of a shape with three sides.

After the performative act, within the social community sharing a common language, the word "the triangle" means "a shape with three sides", and the statement "the triangle has three sides" is true.

As "the triangle" does now refer to something, ie, a shape with three sides, it has a use.

As the word "triangle" is now part of the common language, it can be mentioned as being a word within the common language.

As the word "the triangle" does now exist in the common language, it can play a role in analytic and synthetic statements. The statement "triangles have three sides " is analytic, as this is part of the definition of triangles. The statement "the triangle is orange" is synthetic, as this is not part of the definition of triangles.

There is no a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act. There is only a posteriori knowledge of the word "the triangle" after it has been baptised in a performative act. -

Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguistics"Are there analytic statements?"

In a performative act, I define X as x, y and z.

I tell at least one other person.

There is now a social community sharing the same language that knows that X means x,y and z.

The statement "X is z" is now an analytic statement and it is true that "X is z".

Provided that within a social community sharing the same language, at least one person has made a definition in a performative act, and told at least one other person, yes, analytic statements exist. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Concepts don't exist in the head. They exist in the movements of the body, including the movements of mouth and hand and all the [ other kinds of ] action that claims are used to justify, explain, predict. — plaque flag

Where in my body is my concept of open government.

This is one of the problems with indirect realism. It's dualist ! You are trapped in your head — plaque flag

If trapped in my head, how have I managed to survive X years in a harsh, brutal and unforgiving world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Personally I wouldn't put beliefs 'in the mind. — plaque flag

If my belief that it will rain tomorrow isn't in my mind, how can I know that this is my belief.

Do you see claims through your sense organs ? I think not. — plaque flag

The first claim being that simple ideas come into the mind in the form of nonpropositional awarenesses

The second claim being that these ideas once in the mind somehow get converted into something that can stand in inferential relations to propositions in the mind

As regards claim one, true. I can see many things without knowing its name.

As regards claim two, partly true. Some things I see I do know its name. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Concepts are public. Concepts are norms. — plaque flag

Either the public body is a set of individuals, meaning that concepts only exist in the minds of the individuals making up the public body, or, the public body supervenes on a set of individuals - a non-reductive physicalism - meaning that concepts exist in the public body and not in the minds of the individuals.

As I personally find non-reductive physicalism hard to believe, my belief is that concepts can only exist in the minds of the individuals.

I touch on that in my new thread — plaque flag

:up: -

Is indirect realism self undermining?How have (or could) you establish “my private experience of apple is different to yours”? — Richard B

True, its an assumption, but a reasonably strong assumption.

But if I was a South African cab driver and you were an Icelandic doctor, the chances that our private experiences of apples are exactly the same is highly remote.

From https://scitechdaily.com:

It’s a question that arises with virtually every major new finding in science or medicine: What makes a result reliable enough to be taken seriously? The answer has to do with statistical significance — but also with judgments about what standards make sense in a given situation. The unit of measurement usually given when talking about statistical significance is the standard deviation, expressed with the lowercase Greek letter sigma (σ). The term refers to the amount of variability in a given set of data: whether the data points are all clustered together, or very spread out.

I probably have a six sigma level of confidence. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Here are some good points against indirect realism, IMO. — plaque flag

What Sellars’s “Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind” helped Rorty to show was that a belief can be shown to be justified (or unjustified) only on the basis of another belief or set of beliefs.

The Direct Realist argues that they perceive immediately or directly things in the world.

If a belief can be justified only on the basis of another belief, and beliefs only exist in the mind, then there can be no connection of any kind between the mind and the world. This is more an argument for Idealism than Realism.

A belief cannot be shown to be justified (or not) on the basis of what Sellars mocked in his essay as “the unmoved movers of empirical knowledge” (Sellars 1956, 77).

There is a causal chain from the external world through my senses to my mind

When I see the colour red, I don't believe that I see the colour red, I know without doubt that I see the colour red. I don't need to justify my belief as it is not a belief in the first place.

IE, the Indirect Realist doesn't need to justify what they perceive through their senses. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?They both see the apple directly, but differently. — plaque flag

I directly see the apple, and you directly see the apple, but the apple I see is different to the apple you see. My private experience of the apple is different to yours.

I directly see the colour red, and you directly see the colour red, but the colour red I see is different to the colour red you see. My private experience of the colour red is different to yours.

Then how can there be a public language about apples and the colour red if our private experiences of apples and the colour red are different. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?People can disagree about the world and be wrong about the world, but they are seeing and talking about the world and not their images of it. — plaque flag

If all Direct Realists are immediately and directly seeing the same world, on what grounds can they disagree about what they see.

I can understand Indirect Realists disagreeing about the world, as they are not seeing it immediately and directly, but are dependent on personal interpretation. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Is there no distinction to be drawn and maintained between a direct realist and a naive one? — creativesoul

I'm sure there is, but it is probably very subtle.

According to Wikipedia Naive Realism:

In philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, naïve realism (also known as direct realism, perceptual realism, or common sense realism) is the idea that the senses provide us with direct awareness of objects as they really are.

Could you rephrase this question by dropping "facts" and "external world" out of it? — creativesoul

I was trying to incorporate Wittgensteins 1.1 "The world is the totality of facts, not of things" in the Tractatus

By external world I mean whatever exists external to any mind. The IEP uses the term in their article Locke: Knowledge of the External World -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The world is whatever we as philosophers are talking about..........The philosopher's intention to articulate the truth is intrinsically social and worldly in a strategically indeterminate sense...Wittgenstein is trying to dig deeper, say something about 'eternal' logical-linguistic structure.. — plaque flag

I don't think that in reality you are a Direct Realist, but someone who has the position that the world exists fundamentally in language. Perhaps a Wittgensteinian approach. This is what all the evidence points to. You say i) The master-idea of semantic inferentialism is to look instead to inference, rather than representation, as the basic concept of semantics ii) that what really matters are linguistic norms and iii) "to see the tree is more usefully understood as a claim to "I see the tree".

For the Direct Realist, the world we see around us is the real world itself. Things in the world are perceived immediately or directly rather than inferred on the basis of perceptual evidence.

As you say "A tree is 'made of' leaves and branches, but the tree is no less real because we can consider it as a unity", something the Indirect Realist would agree with, in that we have the tree as a concept in the mind. But the Direct Realist is also saying that this tree exists in the world exactly as we perceive it in our minds.

Using Wittgenstein as a starting position, from the Tractatus

1. The world is all that is the case.

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things

Things in the external world are not static but change with time. For example, the life cycle of a tree has six main stages: seed, sprout, seedling, sapling, adult tree, and decline into coarse woody debris.

The world is all that is the case, and the world is the totality of facts. Facts are states of affairs that obtain in the world and about which we can make true propositions.

The sapling becomes a tree, but the process isn't instantaneous. It requires time for one fact to change into a different fact.

At an earlier moment in time, there is the fact that the sapling is short and we can say "the sapling is short" is true. At a later moment in time there is the fact the tree is tall and we can say "the tree is tall" is true. But there is an intermediary period when neither fact obtains, the fact that the sapling is short doesn't obtain, and the fact that the tree is tall doesn't obtain.

If Direct Realism was true, and we directly perceive things in the world as they are, then every observer will agree about the moment when the sapling changes into a tree, when one fact in the world changes into a different fact.

But we know that different observers will make different judgements as to the moment the sapling changes into a tree, when one fact changes into another fact over an extended period of time.

My question to the Direct Realist is, if all observers are directly observing the same facts in the external world, then why do different observers make different judgements about the moment when one fact changes into a different fact. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Philosophy is often a serious kind of poetry. Yes, we like inferences. But metaphors do much of the lifting. — plaque flag

It is true that "The world is all that is the case", but is this the world of Indirect or Direct Realism.

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein studiously avoids addressing this question. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?I think Gabriel is missing the point. The world as that which is the case is methodically minimally specified. If Gabriel says that that kind of metaphysics is vague, he is describing what is the case, talking about the world --- as whatever is the case. — plaque flag

Wittgenstein's "The world is all that is the case" is poetry.

Robert Frost also talked about the world

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Poetry is fine, but open to numerous interpretations, which is its nature.

If the writer knows his words will be open to numerous interpretations and doesn't find that a problem, then either they are a poet or they are, as Markus Gabriel said, being sloppy about their subject. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?The language, its users, and the world are primordially unified — plaque flag

Not primordial, as language only began about 50,000 to 150,000 years ago.

Users of the same language agree to a basic meaning of a word, even though they can have very different concepts as to its particular meaning. For example, an Australian living in Alice Springs will have a very different concept of the word "grass" to an American living in Spokane.

The world is all that is the case. There is genius in that simple statement. — plaque flag

My approach to "the world is all that is the case" is similar to that of Markus Gabriel:

"In a 2018 interview, Gabriel complained that "most contemporary metaphysicians are [sloppy] when it comes to characterizing their subject matter," using words like "the world" and "reality" "often...interchangeably and without further clarifications. In my view, those totality of words do not refer to anything which is capable of having the property of existence" -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Are you familiar with Markus Gabriel's ideas? — Janus

No, but I will have a look.

From a quick scan on Wikipedia Markus Gabriel, I definately agree with:

"In an April 2020 interview he called European measures against COVID-19 unjustified and a step towards cyber dictatorship, saying the use of health apps was a Chinese or North Korean strategy."

"In a 2018 interview, Gabriel complained that "most contemporary metaphysicians are [sloppy] when it comes to characterizing their subject matter," using words like "the world" and "reality" "often...interchangeably and without further clarifications. In my view, those totality of words do not refer to anything which is capable of having the property of existence" -

Is indirect realism self undermining?To be consistent, the indirect realist cannot say “rock”. The only meaning this term could mean by this theory is “some object” or “something”. — Richard B

As an Indirect Realist, I can say "I see a rock", because the rock I see exists as a concept in my mind. External to my mind is something, but it is not a rock.

In my mind, the rock exists in part as a direct perception and in part as part of language, neither of which are independent of any mind. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?It's the same world viewed by different people with eyes in different places. — plaque flag

Relatively speaking.

There is the ontology of the nature of reality, in that, is the Neutral Monist correct when they argue that reality is elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time. There is the epistemological problem of how we know the nature of reality, given the problem that between our mind and the external world are our senses, and the senses alter any information arriving at our minds from the external world. But we can only discuss these things using language.

But language is a symbolic system, where words symbolise what they represent. Therefore, any understanding we get using language must be founded on a symbolic understanding, where, for example, the word "world" symbolises something else, in this case, the world.

This leads into the philosophical problem of where does language get its meaning. What does the word "world" actually mean. Is there an absolute meaning to "world", or is its meaning relative to its users.

If there is an absolute meaning to "world", then it cannot depend on the users of the language, as each user may use the word differently. Therefore it can only be found outside users of the language. But language wouldn't exist if there was no one to use it, leading to the inevitable conclusion that there can be no absolute meaning to the world "world".

Therefore, the meaning of "world" must be relative to the users of the language. But if meaning is relative to its users, the meaning of the word "world" depends on who is using it. Therefore, no one use is correct. My "world" may be different to your "world", meaning that there is no one meaning of "world" but many. In fact as many meanings as there are people using that language.

It is correct to say "she lives in her own world", where the world exists in the mind. It is correct to say "you are my world", where the world exist in a social community. It is correct to say "there is an unknown world out there", where the world exists external to any mind. It is also correct to say "there is only one world", where the world is the sum of all the above.

We may be worlds apart in our world view, but then again, the world is a strange and mysterious place. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?So, all the indirect realist can say is “some object caused an idea of rock” and “some object caused an idea of cat.” Which then reduces to “some object caused an idea of some object.” We are left with some trivial generality that does not say much. — Richard B

The Indirect Realist would not say "some object caused an idea of some object", as that is presupposing objects like rocks exist in the external world. The Indirect Realist would say that "something caused the idea of a rock". From the position of Neutral Monism, that something is elementary particles and elementary forces in space-time.

One could reword as "something in the external world caused an idea of a rock in the mind"

But one could also say "something in the external world caused the idea of a pain in the mind".

I doubt that anyone would say that pains exist in the external world independently of any sentient being, so why suppose that rocks exist in the external world independently of any sentient being.

Why suppose that just because we perceive something it must exist in the external world. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?We talk about the world we care about --- the world we all live in together. — plaque flag

I talk about my social world, which is something I care about. I talk about the external world, Planet Earth, etc, which is something I care about.

There are different worlds that I talk about.

Two people in the same room see the world through different pairs of eyes. But it's the same world. — plaque flag

Again, more than one world. The world from the person's perspective ,"see the world through different pairs of eyes" and the external world, "the same world".

The fact that I see a stick bent in water doesn't mean that in the external world the stick is bent in water.

Our talk has always been directed toward others and about the one and only world, so it's pretty strange to invent internal images of the world just to explain the fact that people can be mistaken sometimes. — plaque flag

If you see a stick bent in water, you are not mistaken in that you actually see a stick bent in water, but are mistaken in believing that the stick is actually bent in water

If what you saw is not an image, then you would be directly seeing the actual object in the external world.

Then how to explain the contradiction that on the one hand you are not seeing an image of a stick bent in water but directly seeing a stick bent in water and on the other hand are not seeing a stick bent in water.

How are you talking about it then ? It's a product of language, an empty negation. — plaque flag

The external world is not a product of language

I don't need language to be able to see things, there are many things I see that I don't know the name of.

There's nothing strictly wrong about indirect realism talk. It's just clumsy.............My view is that linguistic sociality is absolutely fundamental. — plaque flag

That we have language is not an argument against Indirect Realism

Indirect Realism is the view that you quoted in discussing Reid.

In perception, external objects such as rocks and cats causally affect our sense organs. The sense organs in turn affect the (probably, non-material) mind, and their effect is to produce a certain type of entity in the mind, an 'idea.' These ideas, and not external objects, are what we immediately perceive when we look out at the world. The ideas may or may not resemble the objects that caused them in us, but their causal relation to the objects makes it the case that we can immediately perceive the objects by perceiving the ideas.

As the passage shows, Indirect Realism isn't about the nature of language. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?He opens by sketching indirect realism. Then he makes fun of it. He says fear of error becomes fear of truth. — plaque flag

Fear of error becomes fear of truth is not a reasoned argument.

The Indirect Realist could equally well have said the same.

His solution is to point out that we aren't on the other side of our sense to begin with ---that this was all just a silly unjustified assumption from the beginning. — plaque flag

To say that the Indirect Realist's position that we are separated from the external world by our senses is a silly unjustified assumption is not a very strong argument.

There must be a stronger argument against Indirect Realism that that.

For example, why does Hegel say that it a silly unjustified assumption. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?There is just the one world that we all live in and see and talk about. — plaque flag

The world that we live in and the world that we talk about refer to different worlds. There is more than just one possible world.

When you say "one world that we all live in" this could apply to a world external to any mind. When you say "the world that we...........talk about", this could apply to the world of language within a social community.

In addition, there is the total world, comprising both minds and everything external to minds.

There is also the world as experienced by each individual. It must be the case that each individual perceives the world differently. I cannot believe that the world as experienced by a thirteen year old growing up in Soweto is the same world as experienced by a fifty year old merchant banker in Wall Street, as you seem to be suggesting.

The world that exists outside language is certainly very different to the world existing within language.

Yes we need our nervous systems to do this, but we are not trapped behind or in that nervous system — plaque flag

The Indirect Realist would agree that we are not trapped behind our senses, in that the Indirect Realist has no problem interacting with either other people or the external world.

The world is all that is the case because it is the articulated world we talk about, the shared world we articulate — plaque flag

It seems highly unlikely that for 13.7 billion years before humans first appeared, the Universe didn't exist because it wasn't talked about.

Yes, I need light to come from the apple to my retina. That's part of how I see the apple. But I don't see an image of the apple, and I don't see a private world in which the apple is given directly. I see the apple right there in our world, the world — plaque flag

A wavelength of 700nm enters the eye and an electric signal travels up the optic nerve to the brain.

How is it possible to directly know what is on the other side of our senses, when the information we receive in the brain has come to us indirectly ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Say what now ? Is that a typo ? — plaque flag

No, certainly not a typo, as this is what I have been saying since page 2 of this thread.

The term "Indirect Realist" should be thought of as a name not a description, as some aspects of Indirect Realism are direct and some indirect.

I directly see a tree. There is no doubt about this. The question is, in what world is this tree. There are different worlds, i) the world in my mind ii) the world in the minds of a community iii) the world external to any mind iv) the world as a sum of all these. Problems arise in philosophical discussion when there is ambiguity in the meaning of "world". For example, Wittgenstein in Tractatus para 1 writes "the world is all that is the case.", and creates unnecessary debate by never explaining where this world is.

As Searle wrote:

The relation of perception to the experience is one of identity. It is like the pain and the experience of pain. The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain. Similarly, if the experience of perceiving is an object of perceiving, then it becomes identical with the perceiving. Just as the pain is identical with the experience of pain, so the visual experience is identical with the experience of seeing.

From Searle, the experience of seeing a tree does not have seeing a tree as an object because the experience of seeing a tree is identical with seeing a tree.

We talk about the object and not some private internal image of the object — plaque flag

Exactly, for both the Indirect and Direct Realist. The passage from the IEP is consistent with my statement that "As an Indirect Realist, I directly see a tree, I don't see the image of a tree."

From the IEP Objects of Perception section 2:

The indirect realist agrees that the coffee cup exists independently of me. However, through perception I do not directly engage with this cup; there is a perceptual intermediary that comes between it and me. Ordinarily I see myself via an image in a mirror, or a football match via an image on the TV screen. The indirect realist claim is that all perception is mediated in something like this way. When looking at an everyday object it is not that object that we directly see, but rather, a perceptual intermediary.

It comes down to the fact that there are different worlds that tend to coalesce into a vague and unspecified mystical unknown whenever Indirect and Direct Realism is discussed.

In the world in my mind I directly see a tree and in the world that exists independently of me I indirectly see a tree.

In your support of Direct Realism you referred to Hegel. Hegel clearly sets out the problem with Direct Realism in the passage linked to above.

But what is Hegel's solution to the problem of how can we know what is truly the other side of our senses, when our senses alter what we know about what is the other side of our senses ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Is it socially acceptable to hit a machine that is providing medical assistance to a human being? Probably not, and it would be nonsense to assume the machine has a concept of human pain. — Richard B

No, it wouldn't be, not because of the pain it would cause to the machine, but because of the pain it would cause to the human if they didn't receive medical assistance.

It is also not sociably acceptable to hit pets, not because of the pain it would cause to its owner, but because of the pain it would cause to the animal. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Your pet does not need a concept of digestion in order for it to digest food — Richard B

Neither do humans. But there cannot be any doubt that pets have the concept of hunger, as well as pain, even though they don't have a verbal language with the words hunger and pain.

They are living creatures, not machines, which is why it is not socially acceptable to hit pets as it is socially acceptable to hit machines. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Your use of we is a tacit acknowledge of that inferential norms are public — plaque flag

Exactly, the Indirect Realist believes that there is a world the other side of their senses, an inferential world. A conclusion reached on the basis of evidence and reasoning, not because we have direct knowledge of it.

Hegel was setting up that bowling pin to knock it down. — plaque flag

Hegel clearly sets up the problem - here - as to how we know what is the other side of our senses.

The Indirect Realist argues in Hegel's terms that there is knowledge on one side and an Absolute on the other side.

Within the quote forwarded, Hegel says that this is a presupposition, yet gives no reason or justification why this is a presupposition rather than a fact. He makes a statement.

How does Hegel explain how we can have direct knowledge of the Absolute the other side of our senses, yet such knowledge can only come through our senses, and our senses alter anything that passes though ?

Solipsism can be seen as parasitic upon common sense because it relies on common sense assumptions in order to even be formulated. — plaque flag

The Indirect Realist is not a Solipsist. Indirect Realism is the philosophical idea that other minds exist.

It is absurd to make the sense organs the product of the sense organs because it is a circular

argument. — plaque flag

Neither the Indirect nor Direct Realist would argue that their perceptions are of their sense organs rather than what has passed through their sense organs.

As an Indirect Realist, I directly see a tree, I don't see the image of a tree. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?As I see it, the whole idea that the self is some gremlin in a control room, redeyed peeping at screens, only guessing at what lives outside its bunker, is a wacky viral meme. — plaque flag

There is the screen, which are the senses. The question is, how do we have knowledge of what is on the other side of the screen, the other side of the senses.

Hegel presented the problem in The Phenomenology of Mind where he wrote:

For if knowledge is the instrument by which to get possession of absolute Reality, the suggestion immediately occurs that the application of an instrument to anything does not leave it as it is for itself, but rather entails in the process, and has in view, a moulding and alteration of it.

Or, again, if knowledge is not an instrument which we actively employ, but a kind of passive medium through which the light of the truth reaches us, then here, too, we do not receive it as it is in itself, but as it is through and in this medium.

The problem is, how do we know what exists on the other side of our senses independently of our senses, when all the information about what is on the other side of our senses comes through our senses.

The "Realist" in Indirect Realist means that the Indirect Realist believes that there is a real world the other side of one's senses, and that we can certainly be eaten by alligators. The Direct Realist also believes we can be eaten by alligators. The Indirect Realist and Direct Realist agree that we can only know about alligators through our senses. The Indirect and Direct Realist disagree about in which world this alligator exists. There are different worlds, i) inside the mind, ii) inside the minds of a community, iii) external to any mind and iv) the sum of all these.

My question to the Direct Realist remains. How can we know what is truly the other side of our senses, when, as Hegel pointed out, our senses alter what we know about what is the other side of our senses ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Animals of all sort have no conception of pain but do a good job of avoiding fire. — Richard B

If animals are able to avoid pain but without any conception of pain, then they are no more than automatons, machines. If animals are no more than machines, as it would not be morally reprehensible to hit a machine with a hammer, society would not be disapproving of animal cruelty.

Society is disapproving of animal cruelty because society accepts that animals do have the concept of pain, even if the animal has no verbal language to express it.

For example, see the article Animal cognition and the evolution of human language: why we cannot focus solely on communication -

Is indirect realism self undermining?But it's not. I claim that you've simply adopted bad assumptions from a more primitive era of philosophy. — plaque flag

The self this side of the senses may be in part shaped by what is on the other side of the senses from information passing through the senses, but the self doesn't exist the other side of its senses.

That is, not unless one has the belief in telekinesis, psychic empathy and the paranormal. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?So the person that sees (which is the person that talks about what is seen) is not stuffed in a brain, not trapped behind or as sensations. — plaque flag

That's the problem. The self is this side of our senses, and society is the other side of our senses.

How can we know what exists on the other side of our senses independently of our senses, when we can only know what is on the other side of our senses through our senses.

If a human doesn't learn a language, I don't know how much we can say about them in this context (they would be almost like wild animals?). — plaque flag

I hope you are not inferring that it is ok to kick dogs, in the event that dogs don't have the concept of pain because they have no language. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?@plaque flag

A concept, a word becomes alive with meaning when a community has a use for it. — Richard B

I agree that a concept becomes alive when a community has a use for it, but a concept may still have a private meaning even if a community doesn't have a use for it

If Wittgenstein can use the analogy of a beetle, I will use the analogy of the desert island. Suppose there is someone who has lived their life alone on a desert island. If it is the case that "There are no private concepts.", he has never had the private concept of pain, and has been putting his hand into the fire badly burning it over the years. This is not something that has concerned him if he has no private concept of pain.

Unbeknownst to him, someone else had also been living in isolation on the far side of the island and one day by chance they meet up in the middle of the island.

Now that there are two people, there is a community, a society. Because there is a community, the concept pain takes on a public meaning within the community.

My question is, where exactly is this public concept of pain, if neither of the individuals has the private concept of pain ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?More than any other animal we live in a symbolic realm that we cocreate copreserve and codestroy. — plaque flag

The idea that more than any other animal we live in a symbolic realm is something a supporter of Indirect Realism would say, something that I would say. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?There are no private concepts. — plaque flag

So I learnt my concepts of time and space, good and bad, red and green, easy and difficult, slow and fast, love and hate, freedom and subjugation, clarity and confusion, hot and cold, loud and quiet, justice and inequity, truth and falsity, etc. from society.

But where did society get its concepts from if not from the members of that society ? -

Is indirect realism self undermining?That's where he shows those with eyes to see that meaning is public, concepts are norms. Beetles don't supply meaning. Back then, it made more sense to think Wittgenstein was crazy. — plaque flag

Without private meaning and private concepts there would be no public meaning and public concepts.

If no one ever had the private experience of pain, no one would have any concept of pain, and pain would not mean anything to anyone. In that event, pain would never be discussed in any public language.

Pain is only discussed in a public language because of the private experience of pain..

Wittgenstein's beetle in the box analogy explains in part how private experience is linked to public language. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?A metaphysician 'introspects' and talks about 'Experience' and 'Representation,' which are understood to be private and immaterial and impossible to see from the outside. — plaque flag

Wittgenstein's para 293 of Philosophical Investigations and the beetle in the box analogy may be able to answer your question better than me. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?Why this shift toward talk ? — plaque flag

Because your position throughout this thread has been that "what really matters are linguistic norms", where these linguistic norms are "within/by human communities", yet linguistic norms have nothing to do with the nature of Direct Realism. -

Is indirect realism self undermining?See how you are holding me to linguistic norms, asking me to justify/defend my moves in social space ? — plaque flag

I agree with you that linguistic norms are part of the language game in social space. However, as your own resource sensibly laid out - here - linguistic norms are not part of what Direct Realism is about.

As we can talk about "The Big Bang" without suggesting that linguistic norms were part of what "The Big Bang" was about, we can talk about Direct Realism without suggesting that linguistic norms are part of what Direct Realism is about.

People should be held to linguistic norms when talking about something, but because we use linguistic norms when talking about something, this doesn't mean that what is being talked about has linguistic norms.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum