Comments

-

Matter and Patterns of MatterNo, everything that exists has a pattern/arrangement. — khaled

You wrote "I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter."

The Cambridge Dictionary defines arranges as "to put a group of objects in a particular order" and pattern as " a regular arrangement of lines, shapes, or colours"

They have in common the concept particular order or regular arrangement.

If I understand correctly, you are saying that as everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, then there is nothing that is not in a particular order or regular arrangement.

However, no single part can be in a particular order or regular arrangement, only the whole, the set of parts.

If everything in a mind-independent world is in a particular order or regular arrangement, either each part has information that it is a part of of a particular order or regular arrangement, or the whole has information that its parts are in a particular order or regular arrangement.

How ? -

Matter and Patterns of MatterBut the relations between two groups of things may depend on the regularity of the patterns they (the things) form within their groups, independent of their awareness about each other patterns — Daniel

Keeping with your terminology, accepting that trying to explain a mind-independent world using metaphorical language is inherently problematic, and using "aware" in the sense of having information.

If two things in a mind-independent world have no "awareness" about each other, then how can each thing be "aware" that it is part of a pattern that includes the other thing. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?I was asking what exactly you think is THE formal definition of "exists" in philosophy — busycuttingcrap

As the SEP article on Existence notes that the question of existence raises deep and important problems in metaphysics, philosophy of language, and philosophical logic, it's highly unlikely that I could come up with one. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterOr that the pattern is simply irregular. ABABABABAB is a pattern. ABABBABBAABA is also a pattern. The second being irregular. It is our judgement that it is irregular. But both patterns exist. — khaled

You say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", inferring that before sentient beings there were some things that existed as a pattern and some things that existed as a non-pattern.

It is true that with hindsight a sentient being can judge which was a pattern and which was a non-pattern.

But in the absence of a judgement by a sentient being, either at that time or subsequently, what determines that one thing exists as a pattern and and another thing exists as a non-pattern, particularly when patterns may be regular or irregular. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterElectrons do not have a set location, and they definitely exist in a mind-independent world. — khaled

Electrons are not abstract entities, in that they have a mass and exist in a cloud surrounding an atomic nucleus. It is not that the position of an electron cannot be measured, rather, if you know precisely where a particle is you don't know what direction it is going.

How can something that doesn't ontologically exist be discovered as opposed to imagined? — khaled

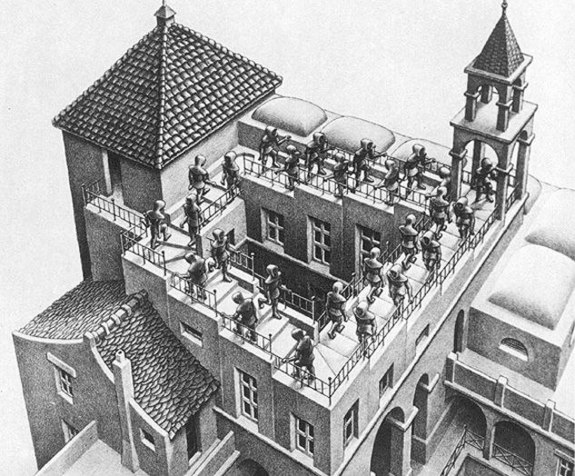

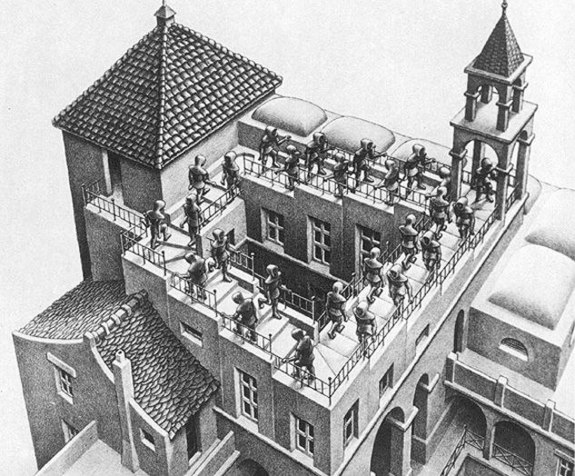

I didn't create or imagine this image, but discovered it on the internet. The ever-ascending stair doesn't exist in the world, even though that is what I observe. What I observe is an illusion, in the same way that patterns I discover in the world are illusions.

We have the ability to notice the abstract patterns that exist (indepencently of us). — khaled

I agree that patterns exist in the mind. The question is, do patterns ontologically exist in a mind-independent world.

A pattern as a whole is a regularity in the parts that make it up. I have no doubt that parts do exist in a mind-independent world, such as elementary particles and elementary forces. What I doubt is that sets of parts in a mind-independent world have an existence as a whole in addition to the individual parts.

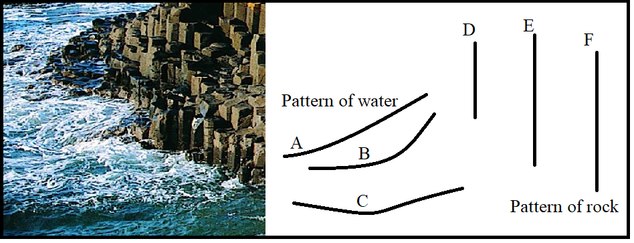

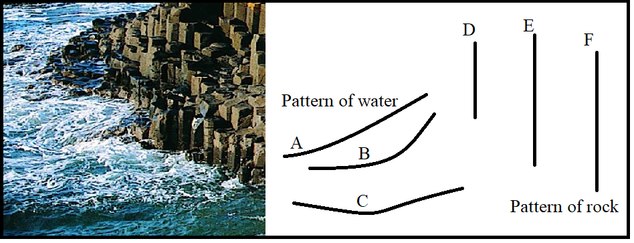

We see a pattern in the rocks of the Giant's Causeway, even though the parts are not exactly regular. How regular does a pattern need to be for us to judge it as a pattern. If the distance between the parts varies by 1mm, the whole is definitely a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 1cm, the whole is probably a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 10cm, the whole may or may not be a pattern. If the distance between parts varies by 1 metre, the whole is definitely not a pattern.

As no pattern is exactly regular, whether the set of parts makes a pattern is determined by the judgement of the observer. There is nothing within the set of parts that is able to judge whether the whole that they are part of is a pattern or not. No part can judge whether it is part of a whole or not. The whole cannot judge that it is a whole made up of parts.

If patterns did ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, then as no pattern can be exactly regular, something within either the parts or the set of parts as a whole would have to have judged whether it was a pattern or not. Without recourse to the existence of a god sitting in judgement as to whether a set of irregular parts was a pattern or not, I don't see this as a possibility.

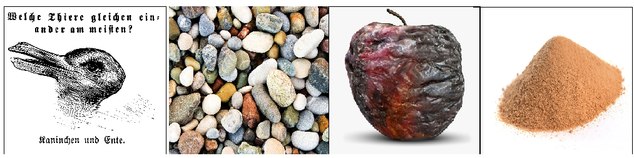

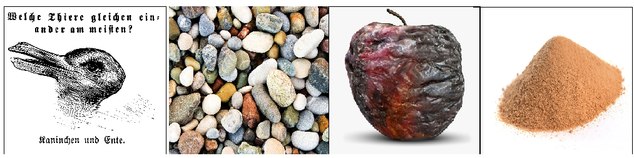

We judge whether the image is of a duck or rabbit, there is no information within the image that determines one way or the other. We judge that the pebbles make a pattern, even though they are neither regularly spaced nor sized, the pebbles cannot make that judgement. We judge when an object such as an apple is no longer an apple, the apple is no judge. We make a judgement in the Sorites Paradox when a heap of sand becomes a non-heap of sand, the sand cannot make any such judgement.

The mind judges when an irregular set of parts makes a pattern or is a non-pattern. If patterns did exist in a mind-independent world, then the problem would be in finding a mechanism within the mind-independent world that determines whether an inevitably irregular set of parts is a pattern or non-pattern. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

I do not see how it can account for relations that have been in effect before being found — khaled

We look at the Giant's Causeway and see patterns in the rocks and adjacent water. The question is, do these patterns, and the relationships between their parts, ontologically exist in the mind-independent world or only in the mind of the observer.

One of my problems with the ontological existence of patterns in a mind-independent world, and the relations between their parts, is where exactly do they exist.

When looking at the image, we know that A and B are part of one pattern and D and E are part of a different pattern.

But within the mind-independent world, where is the information within A that it is part of the same pattern as B but not the same pattern as D. If there is no such information, then within the mind-independent world, patterns, and the relations between their parts, cannot have an ontological existence.

One could say that patterns and relations have an abstract existence, in that they exist but outside of time and space. This leaves the problem of how do we know about something that exists outside of time and space. I could say that I believe that unicorns exist in the world but outside of time and space, but as I have no knowledge of anything outside of time and space, my belief would be completely unjustifiable.

One could say that the force experienced by A due to B is sufficient to argue that as A and B are related by a force, this is sufficient to show that A and B are part of the same pattern. However, even though A may experience a force, there is no information within the force that can determine the source of the force, whether originating from B or D. This means that there is no information within the force experienced by A that can determine one pattern from another.

Question: Sentient beings observe patterns in a mind-independent world, but for patterns to ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, there must be information within A that relates it to B but not D. Where is this information? -

Matter and Patterns of MatterHow do we decide it is wrong? If the pattern doesn't ontologically exist, if it depends only on our minds, then what exactly makes it wrong? If there is no "right" answer in the thing being observed itself, then how can there be wrong answers? — khaled

A pattern cannot be right or wrong. What we infer from a pattern may be right or wrong.

If I notice the pattern that the sun has risen for the last one hundred days in the east, I may infer that tomorrow the sun will again rise in the east. My inference may be right or wrong, not the pattern that I have observed.

Nothing you've presented so far actually shows that relationships ontologically existing creates any problems — khaled

It affects your thesis that "I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter" in the event that patterns of matter don't ontologically exist in a mind-independent world.

There are significant consequences in the event that patterns of matter and the relations within patterns don't ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, in that for example things that we know as "apples", "The North Pole", "mountains", "tables", "trees", etc don't exist in a mind-independent world but only exist in our minds. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterThose geometric patterns emerge through natural processes — Athena

Yes, what we see as patterns have emerged through natural processes in nature millions of years before there was any sentient being to observe them.

I would say that we discover patterns in nature rather than create them in our minds, as it is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in the world around them.

However, any discussion is complicated by the metaphorical nature of language, in that the words "emerge", "natural", "nature", "create", "processes", "discover" and "mind" are metaphorical rather than literal terms. Trying to describe literal truths in a mind-independent world using language that is inherently metaphorical is like trying to square the circle. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterIn order for something to be discovered, it must exist first no? — khaled

When we observe the Giant's Causeway, which existed before sentient observers, we discover a pattern in the relationship of the parts.

It is in the nature of sentient beings to discover patterns in what they observe, and it may well be that different sentient beings discover different patterns from the same observation.

That you discover a duck and I discover a rabbit in the same picture does not mean that either exists in what is being observed.

When we discover a pattern or a relation, we are discovering an inherent part of human nature, not something that ontologically exists in a mind-independent world.

-

Matter and Patterns of MatterThe relation "Have a gravitational pull towards each other" has always been in effect, even before we detected it. Every physical law has always existed even before we detected it, and every physical law fits the definition of a pattern (which is why we can represent it mathematically). — khaled

Patterns and relations exist in the mind of an observer of a mind-independent world

The Moon circled the Earth before humans existed, and in our terms, there was a pattern in how the Moon circled the Earth and there was a relation between the Moon and the Earth.

A pattern needs a relation between parts. I agree that patterns and relations exist in the mind, but do patterns and relations exist in a mind-independent world, because it affects your thesis that " I believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter".

Force is a different concept to relation, in that there may be a temporal relation between two masses yet no force between them. Two masses on either side of the Universe will have a spatial relation yet there be no force between them. There may be a relation between a mass and my concept of the mass yet no force between them. Force should be treated differently to relation.

My belief is that patterns and relations don't exist in a mind-independent world, for the reason that there is nowhere for them to exist.

Consider a system of two masses each experiencing a force as described by the equation F = Gm1m2/r2, the equation of universal gravitation. Mass m1 moves because of a force due to m2, and in our terms there is a relation between m1 and m2 and there is a pattern in the movement of m1 expressed by the equation.

Consider mass m1 experiencing a force. An external observer may know that the force on m1 is due to mass m2 at distance r, yet no observer could discover from an internal inspection of m1 that the force it was experiencing was due to m2 at distance r. Problem one is that the force from a 1kg mass at 1m would be the same force as a 4kg mass at 2m, giving an infinite number of possibilities. Problem two is that mass m1 can only exist at one moment in time, meaning that no information could be discovered within it as to any temporal or spatial change it may or may not have experienced.

Similarly, no internal inspection of m2 could discover any relation with m1. Similarly, no internal inspection of the force on m1 could discover any relation with mass m2, and no internal inspection of the force on m2 could discover any relation with mass m1. No observation internal to the m1, m2 system could discover any relation between m1, m2 and the force between them. Relations cannot be discovered intrinsic to the system m1, m2 because relations don't exist intrinsic to the system m1, m2.

An outside observer of the system m1, m2 may discover the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 because the relation is extrinsic to the system m1,m2. An extrinsic observer of the system m1, m2 would be able to relate the movement of m1, m2 to a force between them determined by the equations F = Gm1m2/r2 and F = ma. The observer would be aware of a relation between m1, m2, and being aware of a relation would be aware of a pattern.

As the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 is not intrinsic to the system m1, m2, by implication, the laws of nature are not intrinsic in a mind-independent world. Similarly, as the relation F = Gm1m2/r2 may be discovered by an outside observer of the system m1, m2, by implication, the laws of nature being extrinsic to a mind-independent world exist in the mind of an observer.

In summary, relations and patterns are extrinsic to a mind-independent world, and exist in the mind of someone observing a mind-independent world. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?What does "'exist' in a formal sense" even mean here? — busycuttingcrap

You wrote: "And colloquially, to say that something exists only as a concept in your mind is simply a different way of saying that something doesn't exist (consider: a conspiracy theory, an imaginary friend, etc)"

As colloquial is defined as informal speech, "exists in a formal sense" contrasts with "exists in a colloquial sense".

You say that in an informal colloquial sense, the sentence "Santa Claus does not exist" means that although Santa Claus exists as a concept in the mind, he doesn't exist in the world.

Contrasted against this, in a more formal academic sense, the sentence "Santa Claus does not exist" is misleading, in that although Santa Claus doesn't exist in the world, Santa Claus does exist as a concept in the mind.

However, I am not even sure that in informal colloquial speech people would say that fictional characters don't exist, otherwise people wouldn't make such significant emotional investment in fictional characters within books and films. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterWhy would justifying the existence of relations be a task for my view specifically? — khaled

It wouldn't be if "patterns of matter" existed only in the mind, but you also say that "All patterns exist independently of anything", and " The pattern of a quadrilateral would exist even if no one discovered shapes with 4 sides", inferring that patterns also exist in a mind-independent world.

I agree that all material things have a location, and when we observe material things we can observe a relation between them, so relations do exist in the mind. So, patterns exist in the mind.

But how do we know that the relation we believe we observe between material things in the world

doesn't actually exist in the world , but is, in a sense, a projection of our mind onto the world. And if relations don't exist in a mind-independent world, then neither do patterns exist in a mind-independent world.

I'm thinking about the problem of "relations" as described in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Relations, which discusses (1) Rejection of both properties and relations. (2) Acceptance of properties but rejection of relations. (3) Acceptance of relations but rejection of properties. (4) Acceptance of both properties and relations. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterAll patterns exist independently of anything. — khaled

A pattern is a repeated relationship between its parts. If there was no relation between the parts, then the pattern wouldn't exist.

For patterns to exist, relations must exist. How do you justify the belief that relations exist, ie, that relations ontologically exist. -

Matter and Patterns of MatterI believe that what exists is matter, and patterns of matter. — khaled

Assuming that matter can exist mind-independently, do patterns of matter exist only in the mind or can they exist mind-independently ? -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?No, I don't see any contradiction in saying that there does not exist a plump old man living at the North Pole delivering presents to children on Christmas, but that there does exist a body of literary/oral traditions involving such a character..............And colloquially, to say that something exists only as a concept in your mind is simply a different way of saying that something doesn't exist (consider: a conspiracy theory, an imaginary friend, etc) — busycuttingcrap

Perhaps the problem is that one moment you use "exist" in a formal sense and then the next moment in a colloquial sense without making it clear, because otherwise, it seems that you are saying that something that exists doesn't exist. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?to say that something exists only as a "concept in a mind", and not in reality or the world, is just another way of saying that that something doesn't exist. — busycuttingcrap

Isn't your position contradictory, when you say: "something exists only as a "concept in a mind" is "another way of saying that something doesn't exist".

If something exists, it exists. The fact that something exists does not mean that it has to exist everywhere. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Frege held rather, that existence is a second order predicate: a property of concepts, not individuals. — Heracloitus

Good old Frege and Russell :100: -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?non-existent things like fictional characters don't exist. — busycuttingcrap

I agree that non-existent things don't exist, and that there shouldn't be a special category of existence for non-existent things. If we accept Bertrand Russell"s On Denoting, then I also agree that Santa Claus is not a referring expression, but rather a quantificational expression.

For Russell, existence is not a first-order property of individuals but instead a second-order property of concepts.

Santa Claus is a fictional character, and as a fictional character doesn't exist in the world, but as we are discussing Santa Claus, Santa Claus must exist as a concept in our minds.

To argue the blanket statement "fictional characters don't exist", accepting that fictional characters don't exist in the world, you must also be able to argue that fictional characters don't exist as concepts in the mind. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?That's one, but here's the thing Saint Nicholas was a real person. I don't know how to deal with that (historical) fact and how it relates to Santa Claus. — Agent Smith

The real Saint Nicholas has many miracles attributed to his intercession, is said to have calmed a storm at sea, saved three innocent soldiers from wrongful execution, and chopped down a tree possessed by a demon.

The fictional Santa Claus is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnight hours on Christmas Eve. Either toys and candy or coal or nothing, depending on whether they have been "naughty or nice".

It is the nature of language that the real can become indistinguishable from the fictional, and vice versa. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?If I may help you to grasp the point here... People can and do use the same kinds of words (e.g. names) for the purpose of referring to people or objects in some contexts and for the purpose of non-referring word-use in others. — bongo fury

"Apple" and "dragon" are concepts that exist in the mind. Concepts are fictional in the sense that they don't exist in the world - in the belief that neither abstracts nor universals ontologically exist in the world.

An "apple" can be instantiated in the world, but a "dragon" cannot be - even though a model of a "dragon" can be instantiated in the world.

"Apple" can refer to either a fictional concept in the mind or an actual instantiation in the world. "Dragon" can only refer to a fictional concept in the mind.

"Apples" and "dragons" both exist, but in different senses. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?That's one way to look at it. What follows if I may ask? — Agent Smith

I'm afraid it's the blurring of fact and fiction in a Postmodern world. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?people can and do use the same words or expressions for different purposes in different contexts. And after all, not existing is what distinguishes fictional characters as such. — busycuttingcrap

As you say "people can and do use the same words or expressions for different purposes in different contexts". Fictional characters exist as fictional characters, and real people exist as real people.

In one sense of "exist", fictional characters exist and in another sense of "exist", real people exist. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Compare the following 4 entities 1. Vladimir Putin 2. Santa Claus 3. Sherlock Holmes 4. Arthur Conan Doyle — Agent Smith

I could play devil's advocate and say that the mainstream media's analysis of real people often approaches that of an analysis of fictional characters.

How many "documentaries" presented as fact are in reality "imaginative speculations". -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?If you hesitate............You know there are no £19 notes — Cuthbert

Yes, I believe that there are no £19 notes and can justify my belief through the Bank of England web site, but I don't know that there are no £19 notes in that I cannot prove that my belief is true. I believe that my belief is true, but I don't know that my belief is true. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?I can prove that £19 notes don't exist in the world — Cuthbert

A challenge.

The Bank of England web site says"There are four denominations (values) of Bank of England notes in circulation: £5, £10, £20 and £50" and "There are over 4.7 billion Bank of England notes in circulation."

One possible proof would be to inspect the 4.7 billion bank notes, but this assumes that only the Bank of England has printed £ sterling notes.

The other possible proof would be to prove true the statement "There are four denominations (values) of Bank of England notes in circulation: £5, £10, £20 and £50".

Both difficult, if not impossible. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?I don't. I was taking a bet. The odds of me winning are proportional to the amount of evidence I have that the North Pole exists. The odds of me losing are proportional to the amount of evidence I have that it doesn't. I think my bet is fairly safe, but nothing is guaranteed. — Herg

The problem is that the evidence that The North Pole exists is descriptive, We may see a travel company advertising "Join us on the family adventure of a lifetime aboard the magical Journey to the North Pole". We may see the documentary "The Last Degree - North Pole Documentary", yet ultimately our evidence is descriptive, is linguistic.

Russell's Theory of Descriptions may be relevant.

As I understand it, in the sentence "The author of Waverly is Scott", the phrase "the author of Waverly" is not a reference to Scott but is a quantifier of "Scott". Similarly, in the sentence "the northernmost point on the Earth is The North Pole", the phrase " the northernmost point on the Earth" is not a reference to The North Pole but is a quantifier of "The North Pole".

Our evidence of the existence of The North Pole may be linguistic descriptions such as "the northernmost point on the Earth", yet as Russell's Theory of Descriptions points out, these descriptions are not references to The North Pole but quantifiers of "The North Pole".

Descriptive evidence therefore doesn't refer to something that may or may not exist in the world but is a reference to another word in the language and is in this sense self-referential.

Evidence that is linguistic is evidence that the language is coherent, not evidence of something that exists outside of language.

Whether you win your bet depends on the decision of the betting company. As the betting company is basing their decision on linguistic evidence, which is more about a coherent language than about what exists outside of language, your win will be based on the coherence of "The North Pole" within language rather than the actual existence of The north Pole outside language. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Is that true? I thought I had £20 in my wallet. I looked and there was £0 I think I just proved something doesn't exist. The 'something' was £20. Its non-existence was proved by inspection. — Cuthbert

The £20 note is a concept in the mind which may be instantiated in particular locations in the world. The £20 note exists as a concept in the mind, regardless of whether it exists in the world or not.

True, you can prove that a particular instantiation of a £20 note doesn't exist in your wallet by inspection.

But as you cannot prove that there are not instantiations of a £20 note other than in your wallet, you cannot prove that £20 notes don't exist in the world. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Santa Claus, alas, doesn't exist. — Agent Smith

How do you know, as it's not possible to prove that something doesn't exist. Are you inferring that the Mariana Trench, for example, doesn't exist because you haven't seen it.

Are you saying that only those things that you have seen exist, and everything you haven't seen doesn't exist? -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?"Concepts". The term is fraught with problems............in the place of wondering about the concept of democracy, consider the way we use the word "democracy".. — Banno

I agree with @Sam26, and also that the concept of "concept" is fraught with problems.

However, how would it be possible to use the word "democracy" in a sentence without having a concept of what the word meant ?

Without language, we wouldn't have the concept of democracy, in that our concept of democracy has come from language, yet without the concept of democracy we wouldn't be able to use "democracy" in language.

For example, thinking about a foreign language, "theluji" means "maji, waliohifadhiwa, nyeupe na ardhi". I may know how every word in a foreign language is defined, but if I have no concept of the meaning of any word, how can I meaningfully use these words in sentences.

If we had no concept behind the words we use in language, we wouldn't be able to meaningfully use them in language. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Walmart and the North Pole both really exist — Herg

Davidson's T-Sentence such as "schnee ist weiss" means snow is white uses a word in inverted commas to refer to something in language and a word not in inverted commas to refer to something in the world.

Therefore, there are two possible interpretations - i) "Walmart" and "The North Pole" both really exist and ii) Walmart and The North Pole both really exist

"Walmart" and "The North Pole" exist in language, otherwise I wouldn't be able to write this sentence.

But how do you know that The North Pole really exists? If by description, then it is knowledge by language. But if knowledge by language, then how does one know whether "The North Pole" refers to The North Pole, something that only exists outside language, or is self-referential, referring to something that only exists in language. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Clearly, I'm running in circles, and leave it to the reader to explain in what sense does Santa Claus exist? How can we instantiate his existence over the North Pole, and yet knowingly, without doubt, know he doesn't exist? — Shawn

If our knowledge is by description, then "Santa Claus" is no less nor no more fictional than "The North Pole"

Denoting phrases

For Bertrand Russell, "Santa Claus" and "The North Pole" are denoting phrases, which have no meaning in themselves. A propositional function containing a denoting phrase is neither true nor false, such as "Santa Claus brings children gifts" or "The North Pole is the northernmost point on the Earth". Only when something is added to the propositional function to turn it into a proposition does the proposition become true or false, such as "it is said that Santa Claus brings children gifts" or "many believe that The North Pole is the northernmost point on the Earth".

Knowledge by description

The vast majority of people only know The North Pole by description rather than acquaintance. We take it for granted that The North Pole exists even though we may never have seen it, yet we take it for granted that Santa Claus doesn't exist although we have never seen him. We know "The North Pole" by description as "the northernmost point on the Earth, lying antipodally to the South Pole, defining geodetic latitude 90° North, as well as the direction of true north." We know "Santa Claus" also by description as "bringing children gifts during the late evening and overnight hours on Christmas Eve of toys and candy or coal or nothing, depending on whether they are "naughty or nice."

The fact that I have never seen Santa Claus is not proof that Santa Claus doesn't exist, as is the fact that I have never seen The North Pole proof that The North Pole doesn't exist.

Our belief in the existence of things we have never seen rests on description, and description is not proof one way or another.

The question is, how do we know things without doubt that have only been described to us. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?What I'm referring to is the fact that Pegasus or Santa doesn't exist in the world, maybe perhaps Meinongs jungle, but we refer to him as if he does. — Shawn

"Pegasus" and "Santa Claus" do exist in our world, which is why we refer to them as if they exist in the world, but this is a world that exists only in our minds.

As it is difficult to justify that relations ontologically exist in a mind-independent world, it would follow that

it would be difficult to justify that things such as "mountains", "factories", "apples", "universities", "governments", "tables", "Pegasus" and "Santa Claus" exist in a mind-independent world.

It would also follow that "Pegasus" and "Santa Claus" don't exist in a possible world of Lewis, they exist in the actual world of our mind. Also, "Pegasus" and "Santa Claus" are not the non-existent things of Meinong's Jungle, they are the existent things of our minds.

These things can only exist in the mind, which is our world, which is why we refer to them as existing in the world. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Fair enough. Do they say that non-actual is not necessarily contradictory to actual? — bongo fury

I doubt it. Not-A cannot be A, but an entity can be fictional. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?My belief is later stated in the OP, that somehow through language we can ascribe ontological placeholders to fictional entities such as Pegasus or Santa Claus. I find this feature of instantiation of imaginary objects perplexing in language. But that's how ordinary language works to my surprise. — Shawn

I can point to any set of words within a language and give the set a name.

For example, I can point to {"creator", "universe"} and give it the name "godlike".

I can point to {"winged", "godlike", "stallion"} and give it the name "Pegasus".

Also, I can point to {"tree", "snake"} and give it the name "trake"

I can point to {"trake", "invisible", "orange"} and give it the name "trakinor"

"Trakinor" is now a placeholder to the fictional entity trakinor, an invisible orange tree-snake. "Trakinor" has instantiated the imaginary object trakinor.

Is it really the case that naming a set of words is perplexing. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?Do you mean, these people deny that "fictional entity" is an oxymoron - or that they have found that reasoning with oxymorons can end well? — bongo fury

In the sense that fictional is not necessarily contradictory to entity. -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?I mean, I'm guessing that didn't end well, as "fictional entity" is an oxymoron? — bongo fury

Not according to the SEP article Fictional Entities, which write: "While London and Napoleon are not fictional entities, some have thought that the London of the Holmes stories and the Napoleon of War and Peace should be classed as special fictional entities."

Also not according to Alberto Voltolini in his book How Ficta Follow Fiction, A Syncretistic Account of Fictional Entities, where he wrote: " I present a genuinely ontological argument in favor of fictional entities. According to this argument, we have to accept fictional entities because they figure in the identity conditions of other entities that are already accepted, namely fictional works." -

In what sense does Santa Claus exist?I find myself confused, as perhaps many young people do when contemplating the existence of fictional entities such as Santa Claus in the real world.........Now, the issue is more perplexing if we endow Santa Claus the ontological placeholder of living over at the North Pole with his reindeer. — Shawn

The North Pole, reindeer and "real" world are as "fictional" as Santa Claus if relations don't ontologically exist in a mind-independent world.

Santa Claus is said to be "fictional", yet in what way is the North Pole, reindeer and "real" world any less fictional.

Gilbert Ryle in his book The Concept of the Mind 1949 included an example illustrating that relations don't exist in the world but do exist in the mind, supporting the idea that relations don't have an ontological existence in the world. A visitor to Oxford upon viewing the colleges and library reportedly inquired "But where is the University ?". Ryle discussed the problem in terms of categories. There is the category 1 of "units of physical infrastructure", including those parts that are said to physically exist in the world independent of the visitor, colleges, library, etc., and there is category 2 "institution", including unseen relations between those physical parts, role in society, laws and regulations, etc. The visitor made the mistake of presuming that the "University" was part of category 1 rather than category 2.

My belief is that the North Pole, reindeer and "real" world are as "fictional" as Santa Claus, as I have yet to come across any persuasive argument that relations do ontologically exist in a mind-independent world. -

Approaching light speed.If an object could actually reach the speed of light would the object become 2 dimensional from everyone else's perspective? — TiredThinker

There is a belief that we travel through time at the speed of light.

Sabine Hossenfelder: Do we travel through time at the speed of light?

If this is the case, objects travel through time at the speed of light yet remain spatially three-dimensional from everyone else's perspective. -

The ineffableBeyond ↪javra's quite valid criticism of that phrasing, Cantor shows that what was previously unknown can indeed be put into words; putting it into words is the act of making it known. — Banno

Although @Javra rightly points out that there is the unknowable in principle and there is the unknown in practice, I don't agree that this renders my quote "only that which is unknown cannot be put into words" invalid. It cannot be the case that something that is unknown can be put into words just because at some future date it happens to become known. If something is known then it can be put into words, regardless of whether it was known or unknown at some date in the past, and where knowing precedes saying what one knows.

"Ineffable" is defined as something too great or extreme to be described in words, such as ineffable joy.

As regards the unknown in practice, at this present moment in time, no one knows the number of sheep on the hill behind the cottage. As the number is unknown, the number cannot be put into words. But as the number is not unknowable in principle, and as no one would say such knowledge is of great or extreme significance, ineffable would not be the correct word to use. As the unknown in practice can be put into words but only after it is known, meaning that when unknown it cannot be put into words, but when known it can be put into words. One can say that the unknown cannot be put into words, but in this case, the unknown is not ineffable.

As regards the unknowable in principle, although I know my pain, I don't know the pain of others. The pain of others is unknowable in principle. In this case the unknown cannot be put into words, and because of great or extreme significance is ineffable.

Therefore, neither the unknown in practice and the unknowable in principle can be put into words, though only the unknowable in principle may be defined as ineffable.

The problem is, how does one talk about the ineffable, that which cannot be described in words. As previously set out: i) remain silent about it, ii) ignore any referent, iii) treat it as a second-order predicate, iii) describe what it isn't, iv) not talk about it but experience it, v) treat it as a metaphor or vi) ignore any possible relevance.

Perhaps we should take the example of Cantor, who discovered the concept of transfinite numbers, numbers that are infinite in the sense that they are larger than all finite numbers, yet not necessarily infinite.

i) is incorrect in that we obviously don't remain silent about infinity

ii) is incorrect in that we don't ignore the referent, which is infinity

iii) is possible, in that the second order predicate "is infinity" designates a concept rather than an object.

iv) is not correct, in that we cannot experience infinity

v) is possible, in that language is metaphorical.

vi) is incorrect, in that we don't ignore any possible relevance of infinity.

This leaves treating "infinity" either as iii) a second-order predicate or v) a metaphor.

A metaphor is the application of a predicate that is not in the appropriate category for what is being referred to, allowing a hidden essence or attribute of the predicate to be made visible by allowing a category mistake. For example, "God the Father" is a metaphor as God can neither be the father of humans or a male. By giving the object "God" the predicate "the father", we are making a clear category mistake, but enabling us to experience the character of God more clearly. We could say "God is infinite", which is a metaphor. We could say "transfinite numbers are infinite", which is a metaphor. By comparing an unknown object with something else using metaphor, we get closer to what that object is.

But second-order predicates as part of language are metaphorical. The conclusion is that we use the word "ineffable" for those situations that are unknowable in principle, are of great or extreme significance and are described metaphorically. -

The ineffableDo we….or do we not….still need to stipulate the criteria for determining how the unknowable isn’t a mere subterfuge? Seems like that would be the logical query to follow, “only the unknown cannot be put into words”. — Mww

Subterfuge is about deceit, in that we are being deceived in some way. Are we being deceived that the unknown is in fact known?

As @Javra writes, there is the unknowable in principle and there is the unknown in practice. The unknowable in principle cannot be put into words. The unknown in practice can be put into words but only after it is known, meaning that when unknown it cannot be put into words, but when known it can be put into words. It remains true that "only the unknown cannot be put into words"

Are we being deceived about the unknown or is the unknown just a fact of the limits of the intellect. Every animal has a natural limit to its intellectual powers, limited by the physical nature of its brain. Is the horse being deceived that allegories in The Old Man and The Sea will always be unknowable to it, no, it is just a fact. The human is an animal, and similarly, we are not being deceived that some things will always be unknowable to us, it is just a fact.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum