Comments

-

How can one know the ultimate truth about reality?But I wonder also whether the quest to identify the 'really real' might not just be a secular replacement for god. — Tom Storm

I wonder whether even if we knew that the ultimate truth about reality was God, would we be any more knowledgeable than knowing that the ultimate truth about reality was 42. -

How can one know the ultimate truth about reality?reality — A Realist

What reason do you have for assuming that we can ever know the ultimate truth about reality? -

Is the number 1 a cause of the number 2?Without 1, 2 could not exist, though the reverse doesn’t hold. Since it is because of the existence of 1, or one thing, that there can be 2, or two things, then the former can be said to be the cause of the latter. — Pretty

Presumably "exist" is referring to existing in the world rather than existing in the mind.

2 is the relation between 1 and 1.

The question to ask is, do relations ontologically exist in the world.

If relations don't ontologically exist in the world, then there is no relation between 1 and 1. This means that there is no 2. As there is no 2, the concept of did 1 and 1 cause 2 is not applicable.

If relations do ontologically exist in the world, then there is a relation between 1 and 1. However, such a relation is contemporaneous with 1 and 1. On the one hand, the relation between 1 and 1 didn't exist prior to there being a 1 and 1 (as the relation is between 1 and 1) and on the other hand, the relation between 1 and 1 didn't exist subsequently to there being a 1 and 1 (otherwise for a moment in time there would have been no relation between 1 and 1). As the relation between 1 and 1 is contemporaneous with 1 and 1, the concept of cause is not applicable.

Either way, whether relations do or do not ontologically exist in the world, the concept of cause is not applicable to numbers. -

Hypostatic Abstraction, Precisive Abstraction, Proper vs Improper NegationDo you mean that we can measure 'sweet', but we cannot measure 'sweetness'? — Mapping the Medium

Taking wine as an example, the more residual sugar there is in a wine the sweeter it will be. For example, a dry wine could have 1 gms/litre of residual sugar whilst a sweet wine could have 45 gms/litre of residual sugar. The amount of residual sugar defines how sweet a wine is. ( www.wineinvestment.com).

We can measure how sweet a particular wine is. For example, a wine may have 20 gms/litre of residual sugar. This gives us a concrete fact.

We also know that the sweetness of wine varies between about 1 gms/litre and about 45 gms/litre of residual sugars. Any wine will lie within this range. This gives us another concrete fact.

Therefore, how sweet a wine is is a concrete concept, tangible in the same way that apples and chairs are concrete concepts.

The sweetness of wine is an abstract concept, in that it is not tangible as apples and chairs are.

However, both "sweet" and "sweetness" are measurable. "Sweet" is measurable as 20 gms/litre of residual sugar. "Sweetness" is measurable as lying between 1 and 45 gms/litre of residual sugar. -

Hypostatic Abstraction, Precisive Abstraction, Proper vs Improper NegationHypostatic abstraction is a formal operation in logic that transforms a predicate into a relation. For example, "Honey is sweet" is transformed into "Honey has sweetness". — Mapping the Medium

I have no access to what Peirce wrote about hypostatic abstraction, so I cannot comment about what he said.

Can "honey is sweet" be transformed into "honey has sweetness"?

As colour has different hues, sound has different pitches, there are different scales of pain, there are also different intensities of sweetness. For example, a mango can be very sweet, honey reasonably sweet and a watermelon slightly sweet.

In ordinary language we can say "this honey is sweet", meaning that this honey has one particular intensity of sweetness.

When we say "this honey has sweetness", we mean that this honey has a sweetness within the range very sweet to slightly sweet.

"Sweet" is a concrete concept, whilst "sweetness " is an abstract concept.

As the expressions "honey is sweet" and "honey has sweetness" have different meanings, one cannot be transformed into the other. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonAs the axioms do not contradict each other, it is still true that logic is one coherent system. — A Christian Philosophy

Axioms are assumptions taken to be true.

As there is no logical necessity that assumptions don't contradict each other, there is no logical necessity that axioms don't contradict each other.

===============================================================================

Based on it, we build planes that fly. — A Christian Philosophy

We also build planes that crash. -

What is the (true) meaning of beauty?Beauty (as I see it) generally seems soft and cloying. — Tom Storm

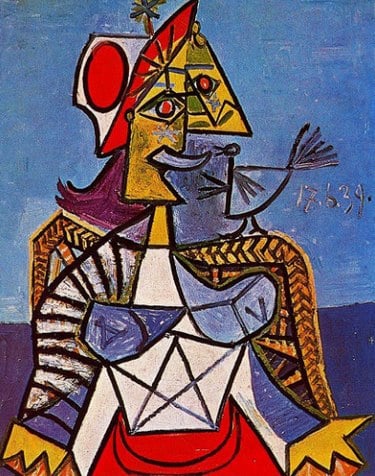

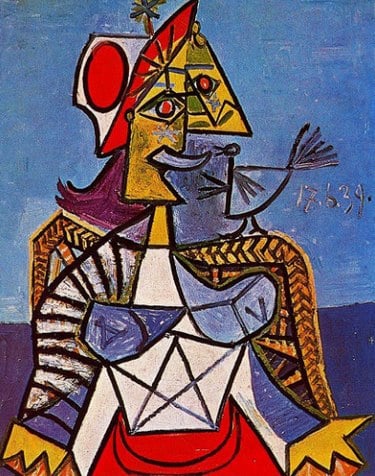

I agree. I think that the distinguishing feature of art is that it has an aesthetic.

Such an aesthetic can either be beautiful, when non-threatening, such as paintings of roses and sunsets or ugly, when threatening, such as paintings of scorpions and war.

When a good aesthetic becomes a great aesthetic then it becomes sublime.

The aesthetic, being a certain combination of balance within variety of form can apply to all disciplines, whether painting, dance, music, architecture, as well as the design of cars. -

Ontological status of ideas"This is why any rational person will reject determinism." — Metaphysician Undercover

Not many people in history have said that Einstein was not a rational person.

From Einstein’s Mystical Views & Quotations on Free Will or Determinism

Thus, in 1932 Einstein told the Spinoza society:

“Human beings in their thinking, feeling and acting are not free but are as causally bound as the stars in their motions.”

Einstein’s belief in causal determinism seemed to him both scientifically and philosophically incompatible with the concept of human free will. In a 1932 speech entitled ‘My Credo’, Einstein briefly explained his deterministic ideology:

“I do not believe in freedom of the will. Schopenhauer’s words: ‘Man can do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wills’ accompany me in all situations throughout my life and reconcile me with the actions of others even if they are rather painful to me. This awareness of the lack of freedom of will preserves me from taking too seriously myself and my fellow men as acting and deciding individuals and from losing my temper.” -

Ontological status of ideasIf something is uncaused then it occurs for "no reason at all." — Count Timothy von Icarus

True. For both Free Will and Determinism, there is a reason why at 1pm I choose not to fire my gun.

===============================================================================

What is self-determining is not undetermined. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree

===============================================================================

At 1pm, when I choose not to fire my gun, I have several thoughts, including the innocence of civilians and the orders I have been given by my superiors.

If Free Will is the case, at t seconds before 1pm, where t can be any number, it has not been determined whether I do or do not have the thought at 1pm to fire my gun.

If Determinism is the case, at t seconds before 1pm, where t can be any number, it has been determined that I have the thought at 1pm not to fire my gun.

My question is, if Free Will is the case, is this not an example of spontaneous self-causation.

Spontaneous in the sense that my thought not to fire could not have existed at t seconds prior to 1pm, otherwise my thought would have been determined.

Self-caused in the sense that the thought at 1pm not to fire caused its own existence.

How can a thought spontaneously cause its own existence? -

Ontological status of ideasSimply put, "choice" is not an appropriate word in this context, otherwise we'd be saying that water makes choices, rocks make choices, etc.. — Metaphysician Undercover

I disagree.

If Determinism is the case, a person has no choice in what they choose.

In language, the word "choose" is used in certain ways. Inanimate things such as rocks that don't possess life cannot choose, but animate things such as people that do possess life can choose.

A person may choose between two courses of action, such as whether to stay or to go, regardless of whether they live in a world that is Deterministic or in a world where people have Free Will.

A larger question is, how does Free Will explain the spontaneous self-causation of thoughts and thoughts to act? -

Ontological status of ideasSo if determinism is true, then someone made the choice for the person? Who would that be, God? — Metaphysician Undercover

As the SEP article on Causal Determination writes

Determinism: The world is governed by (or is under the sway of) determinism if and only if, given a specified way things are at a time t, the way things go thereafter is fixed as a matter of natural law.

If someone happens to be in the middle of a city road and sees a truck directly approaching, they would sensibly choose to move to the pavement.

I agree that some people may believe that God directly told them to move, looking out for their best interests.

Some people may believe that someone else, such as a loved one, telepathically told them to move.

It could be that they move because of an innate instinct for self-preservation, without being consciously aware of what they are doing

It is unlikely that someone other than the person themselves made the choice to move to the pavement.

If Free Will is the case, then they themselves freely made the choice.

If Free Will is the case, and a person's thoughts and thoughts to act come into existence at one moment in time, not having any prior cause, then this is an example of spontaneous self-causation, a metaphysical problem difficult to justify.

If Determinism is the case, their choice had been determined, not by themselves, not by someone else, but by the physical temporal nature of the Universe. A Universe of fundamental particles and forces existing in space and time over which no person has control.

If Determinism is the case, a person has no choice in what they choose. One advantage of Determinism is that it avoids the metaphysical problem of spontaneous self-causation whilst still explaining a person's choices. -

What is the (true) meaning of beauty?Pablo Picasso. Not beautiful, but an aesthetic art, even though ugly.

-

What is the (true) meaning of beauty?"Beautiful.", was the first word that came to my mind then. However, what I had felt and seen seemed much more profound than just one word, which I would say only captured/described but a fraction of this moment. — Prometheus2

Another word is "sublime"

From Edmund Burke: Delineating the Sublime and the Beautiful

Edmund Burke, an 18th-century philosopher, is best known for his exploration of aesthetics, particularly his distinction between the “sublime” and the “beautiful.” In his influential work A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), Burke examines how these two concepts, though related to art and nature, invoke radically different emotional responses in the observer. While beauty tends to elicit feelings of love, calmness, and attraction, the sublime is linked with awe, terror, and a sense of the vastness that surpasses human understanding. -

Ontological status of ideasTherefore you contradict yourself. You admitted that people do not choose if determinism is true, based on my explanation of the requirements for "making a choice". Now you claim a premise which contradicts this. You say "it has been determined that they do make choices". — Metaphysician Undercover

The particular meaning of a word having several possible meanings depends on its particular context.

According to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, one meaning of "choice" is "the act of choosing", such as a person made the choice as to whether to stay or go. Another meaning of "choice" is "a person or thing chosen", such as a person chose the option to stay.

If Determinism is the case, in one sense people do make choices, such as do I stay or do I go, but in another sense cannot choose, as their choice to stay has already been determined.

The fact that a person makes a choice says nothing about whether it is a free choice or a choice that has been determined.

The context of a word is important for its intended meaning. -

Ontological status of ideasThis is why any rational person will reject determinism. — Metaphysician Undercover

A brave statement to call everyone from Heraclitus to Aristotle to Hume to Dennett not rational people.

Wikipedia - Determinism

===============================================================================Determinism was developed by the Greek philosophers during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE by the Pre-socratic philosophers Heraclitus and Leucippus, later Aristotle, and mainly by the Stoics. Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyam, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, more recently, John Searle, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett.

Sure, but believing in determinism is by this description, a belief that choice is impossible. — Metaphysician Undercover

True

===============================================================================

an irrational person (a person who believes that doing the impossible is possible) — Metaphysician Undercover

True

===============================================================================

This would also mean that only an irrational person (a person who believes that doing the impossible is possible) would even attempt to make a choice if that person believed in determinism..................................Therefore the person who believes in determinism, in order to be consistent with one's believe, would not choose to do anything, would be overcome by forces, and would be dead very soon....................Therefore by Occam's Razor we should all believe in determinism, choose to do noting, be dead soon, and get it over with. — Metaphysician Undercover

Not true.

If a person believes in Determinism, not only i) do they believe that their choices have been determined but also ii) it has been determined that they do make choices. -

Ontological status of ideasOne would consider "should I go", and all the merits and reasons for going, independently from "should I stay", and all of its merits and reasons. But the two distinct groups of values could never be compared, or related to each other in any way, because that would require having both of the two contradictory thoughts united within the same thought. Of course this would completely incapacitate one's ability to choose, because a person could never have the two distinct, and incompatible sets of values within one's mind at the same time. To think of one the other would have to be completely relegated to memory, Therefore the two could never be compared. — Metaphysician Undercover

You make a strong argument.

I agree, as you argue, that if there are two contradictory ideas "should I go" or "should I stay", in order to be able choose between them, I must first fuse or unite them into a single idea. It then follows that I have in my mind two contradictory ideas at the same time.

However, consider the following:

At 1pm, I go.

At 12.50pm, I have the two ideas "should I stay" or "should I go".

Free Will means that at 12.50pm I could equally stay or go at 1pm.

Determinism means that at 12.50pm it has already been determined that I go at 1pm.

If Determinism is the case

1) It has already been determined at 12.50pm that I go at 1pm

2) This means that no decision needs to be made at 1pm whether to stay or to go, as the decision has already been made prior to 1pm.

3) This means that it is not necessary to choose between two contradictory ideas at 1pm.

If Free Will is the case

1) At 12.50pm, I have two contradictory ideas, "should I stay" or "should I go".

2) At 1pm, these two contradictory ideas have been fused into the single idea "should I stay or go" in order to allow me to be able to choose between the two possibilities.

Summary

It is observed that I go at 1pm

As you say, Free Will can only account for my going at 1pm by fusing two contradictory ideas into a single idea in order to be able to make a choice between them.

However, Determinism can also account for my going at 1pm without any necessity to fuse two contradictory ideas into a single idea.

By Occams Razor, Determinism is the simplest explanation, as it doesn't require the metaphysical problem of how two contradictory ideas may be fused into a single idea. -

Ontological status of ideasI'm going to try doing some math while writing sentences. — Patterner

Hopefully, not whilst driving.

Perhaps the law on the use of mobile phones whilst driving shows that even the Government accepts the difficulty in carrying out two acts both requiring different thoughts at the same time.

For example, from Drivers Domain UK

The Highway Code states that you must exercise proper control of your vehicle at all times. You are not allowed to use a hand-held mobile phone or similar when driving..............However, the main issue of using a mobile phone when driving is the issue of excessive cognitive load. Drivers simply can’t concentrate when driving and engaging in a detailed conversation!

In practice, it seems that humans have great difficulty in having two different thoughts at (exactly) the same time. -

Ontological status of ideasI did not try writing what I was speaking so that I would not be wondering that very thing. — Patterner

The singing could have been employing a "muscle memory" rather than active thought, allowing you to carry out another task that did require an active thought.

Wikipedia - Muscle Memory

Muscle memory is a form of procedural memory that involves consolidating a specific motor task into memory through repetition, which has been used synonymously with motor learning..................................... Muscle memory is found in many everyday activities, such as playing musical instruments.

How about writing one new post to person A and telling a different new post to person B at the same time? -

Ontological status of ideasSo, as I said, if the person is just learning the word "pain", the person might have a feeling, and consider both thoughts at the same time, "this is pain", "this is not pain", not knowing whether it is pain or not pain, and trying to decide which it is. — Metaphysician Undercover

We were talking about having contradictory ideas, at the same time, concerning one event. I don't see why this is so hard for you to understand, It's called "indecision" — Metaphysician Undercover

Thinking about two contradictory ideas at the same time is commonly called "deliberation". — Metaphysician Undercover

Thinking is one type of act, and the question is whether having contradictory thoughts at the same time is evidence of free will or determinism. You fear that it is evidence against determinism, so you deny the obvious, that we have contradictory thoughts. — Metaphysician Undercover

Both indecision and deliberation require consecutive ideas. Perhaps I will stay, no, perhaps I will go.

I agree that free will requires the ability to have contradictory thoughts at the same time. The person is then free to choose between them. The question is, is this possible. If not, then Determinism becomes a valid theory.

A person feels something. They have one idea that the feeling's name is "pain", and they have another idea that the feeling's name is "not pain".

You are saying that a person can have two contradictory ideas at the same time.

I am saying that this is impossible, in that it is not possible to have the idea that something is "pain" and "not pain" at the same time. -

Ontological status of ideasI'm often amazed beyond description by the speed and scale at which things happen. So I can't guarantee I don't switch back and forth every few microseconds. But it certainly doesn't seem that that's the case. — Patterner

Interesting experiment.

I tried writing "four" whilst speaking "four". The problem was that it took me four times as long to write "four" as to speak "four", meaning that it was difficult to know whether I was thinking about writing the word at the same time as I was thinking about speaking the word. -

Ontological status of ideasI am feeling pain in my finger, I am not feeling pain in my finger, as real possibilities, at the same time. — Metaphysician Undercover

I still cannot understand how a person can feel a pain and not feel a pain in their finger at the same time.

===============================================================================

Muscle memory does not exclude conscious thought. — Metaphysician Undercover

From Wikipedia - Muscle Memory

===============================================================================When a movement is repeated over time, the brain creates a long-term muscle memory for that task, eventually allowing it to be performed with little to no conscious effort.

However, if you have ever taken a look at how this multitasking actually occurs, you'll see that there is constant switching of which act receives priority. — Metaphysician Undercover

That is exactly what I am saying, attention is switched between events, first one, then the other. But not at the same time.

===============================================================================

I agree that there is ongoing debate amongst neurologists etc., concerning how many different tasks a person can "focus" on... They assume the phrase to mean directing one's attention toward one activity only — Metaphysician Undercover

That's my position, where attention is directed towards one activity only.

===============================================================================

You deny the reality of this fact, so you point to a person's actions, and say that a person cannot express, or demonstrate, through speaking, or writing, contradictory ideas at the very same moment. But all this really does, is demonstrate the physical limitations to a human beings actions. — Metaphysician Undercover

I agree, human beings are limited in what they can do.

===============================================================================

It is very clear that we actively think about a multitude of ideas at the same time, that's exactly what the act of thinking is, to relate ideas to each other. — Metaphysician Undercover

This is important point.

I can understand that a person having a painful finger can think about the pain, and later, after the pain has dissipated, think about there being no pain in their finger, but I cannot understand how a person can feel a pain and not feel a pain in their finger at the same time.

I agree that a person can remember having first a painful finger and later a pain-free finger, and can then think about the relation between a painful finger and pain-free finger.

Even if it were impossible, as I think it is, to have a single thought about two contradictory events, this raise the question as whether it is possible to have a single thought about the relation between two contradictory events.

What are relations?

If I think about a relation between two different things, does what I think about include what is being related?

This is getting into Kant's transcendental unity of apperception territory.

===============================================================================

However, since you are unwilling to accept the reality that people have contradictory ideas within their minds, you have now proceed to exclude the memory as part of the mind. — Metaphysician Undercover

I totally agree that people have contradictory ideas within their memories, but not that they are thinking about two contradictory ideas at the same time.

===============================================================================

Philosophy has as its purpose the desire to learn. If your prejudice is so strong, that you are forced into absurd assumptions to support this prejudice, instead of relinquishing it, to adopt a more true path, I consider you are not practising philosophy at all, but professing faulty ideas. — Metaphysician Undercover

Unfortunately, I am not persuaded to follow the "true path" that you are laying out for me.

If Determinism is truly a philosophically faulty idea, then at least I am in good company.

From the Wikipedia article on Determinism

===============================================================================Determinism was developed by the Greek philosophers during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE by the Pre-socratic philosophers Heraclitus and Leucippus, later Aristotle, and mainly by the Stoics. Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyam, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, more recently, John Searle, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett.

To make a proper comparison, you would need to say, as the second premise in the first argument, "I have the thought that I am writing this post". — Metaphysician Undercover

P1 - If Determinism is false, then my thoughts have not been determined

P2 - If Determinism is true, then my thoughts have been determined

P3 - I have the thought that I am writing this post

C1 - Therefore my thought may or may not have been determined

P1 - If Determinism is false, then my thoughts have not been determined,

P2 - I have the thought that I am writing this post

C1 - Therefore my thought has not been determined

P1 - If Determinism is true, then my thoughts have been determined

P2 - I have the thought that I am writing this post

C1 - Therefore my thought has been determined

Having a thought is not sufficient evidence for either Determinism or Free Will. -

Ontological status of ideasIf one part of your finger is touching an ice cube, and you hold a match to another part of your finger, then you would be feeling hot and cold in your finger at the same time. — Patterner

I can have the thought of coldness, and can then have the thought of hotness, but the question is, is it possible to have a single thought of both coldness and hotness at the same time.

===============================================================================

Or you are an eternal being that has always existed — Patterner

Possible.

If I didn't exist, then I couldn't think

I think

Therefore I am -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonThere are several branches of logic but the science of logic as a whole is one coherent system. E.g. fuzzy logic is a branch that may be more suitable than other branches in some cases, but the different branches of logic do not contradict each other. — A Christian Philosophy

A logic system is built on axioms.

From The Foundations of Logical Reasoning: Axioms of Logic

Logic is the backbone of mathematical reasoning, providing the structure and rules that govern the validity of arguments and proofs. At the heart of logic are axioms—fundamental truths accepted without proof. These axioms serve as the foundational building blocks from which all logical reasoning is derived.

Axioms are assumptions taken to be true

From Wikipedia - Axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments.

As any logic system is built on axioms, which are assumptions taken to be true, no one logic system exists necessarily. -

Ontological status of ideasHowever, the fact that they cannot both be said by the person at the same time does not imply that the person cannot have both ideas within one's mind at the same time. — Metaphysician Undercover

If it were possible to have two contradictory thoughts at the same time, then I could feel pain in my finger and not feel pain in my finger at the same time.

Language mirrors thoughts.

If it were possible to have two contradictory thoughts at the same time, then language would mirror this. For example, the proposition would be "I feel x in my finger", where "x" means feeling both pain and no pain at the same time.

However this is not the case. In language we say "one hour ago I felt no pain in my finger but now I feel pain in my finger".

Language by its very nature acknowledges that contradictory thoughts cannot be contemporaneous.

===============================================================================

Clearly people multitask, so they are thinking different ideas at the same time, required to do a number of different things at the same time, even though they cannot say everything that they are doing, all at the same time. — Metaphysician Undercover

A cyclist multi-tasks when they pedal and watch the road ahead at the same time. But thoughts about the road ahead should not be confused with the muscle memory of pedalling, which doesn't require thoughts.

A student multi-tasks when writing an essay and listens to music at the same time. But thoughts about what to write should not be confused with an instinctive pleasure in hearing music.

Musical pleasure and reward: mechanisms and dysfunction

===============================================================================Most people derive pleasure from music. Neuroimaging studies show that the reward system of the human brain is central to this experience. Specifically, the dorsal and ventral striatum release dopamine when listening to pleasurable music, and activity in these structures also codes the reward value of musical excerpts.

How do you account for a person having many different ideas, in one's memory, all at the same time, which one cannot all say at the same time? — Metaphysician Undercover

I have many memories, none of which I am actively thinking about at this moment in time.

===============================================================================

Sure, you can state irrelevant conditionals, just like I can say that if I was not born yet, I would not be writing this right now, but such conditionals are not relevant to reality. — Metaphysician Undercover

Conditions in thought are essential to life:

If I don't eat, then I will die

If I cross the road now, then the approaching truck will run me over

If I don't apply for this job then it is unlikely that they will hire me

If an asteroid 15km in diameter hits the Earth, then most life may become extinct.

===============================================================================

Your if/then statement reveals nothing more than "if I was not born yet I would not be writing this right now" reveals. How do I get from this to believing that I was not born yet? And how do you get from your if/then statement to believing that determinism is the case? — Metaphysician Undercover

One cannot.

If I had not been born, then I would not be writing this post

I am writing this post

Therefore I was born

If Determinism is the case

then all thoughts are determined

I have the thought that my thoughts are not determined

therefore my thought that my thought has not been determined has been determined -

Ontological status of ideasthen it should be called inevitablism, not determinism. Having determined something will happen is not the same as it being inevitable. — Barkon

Determinism seems to encompass more than Inevitabilism, and includes the concept of inevitability.

From Wikipedia Determinism

Determinism is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable

Wiktionary - Inevitabilism

The belief that certain developments are impossible to avoid; determinism.

Wiktionary - Determinism

The doctrine that all actions are determined by the current state and immutable laws of the universe, with no possibility of choice. -

Ontological status of ideasIf determinism is true, and (it; who? What?) determines all our thoughts and actions — Barkon

OK. If Determinism is the case, and all our thoughts and actions are already determined, then your thought that you are free to choose is just another of those thoughts that have already been determined.

Determined by the nature of the Universe. -

Ontological status of ideasIf determinism is true that all our actions are determined. That's all. It doesn't mean it's determined by causes external to our will. If it's determined that I will write this, then all that means is that it was probable that I would, thus it was determinable prior to the act. — Barkon

My understanding of Determinism is that your writing your post was inevitable, not probable.

From Wikipedia Determinism

Determinism is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable

From SEP - Causal Determinism

In order to get started we can begin with a loose and (nearly) all-encompassing definition as follows:

Determinism: Determinism is true of the world if and only if, given a specified way things are at a time t, the way things go thereafter is fixed as a matter of natural law. -

Ontological status of ideasThis is a faulty argument because your designated time of "1pm" is completely arbitrary, and not representative of the true nature of time. As indicated by the relativity of simultaneity a precise designation of "what time it is", is frame of reference dependent.........................Do you agree, that by the special theory of relativity, event A could be prior to event B from one frame of reference, and posterior from another frame of reference? — Metaphysician Undercover

In my location, 1pm is simultaneous with my picking up a cup of coffee.

===============================================================================

As I explained in my last post, having two contradictory ideas at the same time is exactly what deliberation consists of. "Should I stay or should I go". — Metaphysician Undercover

This is why the words in the proposition "should I stay or should I go" are sequential. First one asks "should I stay" and then at a later time one asks "should I go".

Propositions, in that they mirror thoughts, are sequential.

===============================================================================

The problem here, is that you are treating a human subject as if one is a material object, to which the fundamental laws of logic (identity, noncontradiction, excluded middle), apply. — Metaphysician Undercover

This is the case in a Deterministic world.

===============================================================================

What's the point to even asking why matter obeys God, if you do not even believe that matter obeys God. — Metaphysician Undercover

It is not only a question of whether or not matter obeys God, it is also the question of is there a God.

===============================================================================

I know that I am free to choose, from introspection, analysis of my own experience. — Metaphysician Undercover

If Determinism is the case, and determines all our thoughts and actions, then your thought that you are free to choose is just another of those thoughts that have already been determined. -

Ontological status of ideasThere can be thoughts not resulting in acts.

For example, I may think that Monet's "Water-lilies" is aesthetic or I may think that it is not aesthetic. Neither thought requires me to act on the thought. -

Ontological status of ideasWhy does something being determined mean that the person has no control? Perhaps it's just predictable behaviour. — Barkon

If Determinism is true, then all our thoughts and actions are determined by causes external to our will. Our future is already written, and all our thoughts and actions are a consequence of preceding events.

In that sense, if all our thoughts and actions are determined, then it is true that we have no control.

However, in ordinary language, we do say things like "he was determined not to waste a single minute of his time" and "she was weak and the pain was excruciating, but she was determined to go home."

But the fact that a person is determined to do something, does not mean that their determination cannot be explained within Determinism.

If Determinism determines all our thoughts and actions, our being determined is just one of these thoughts, meaning that it is Determinism that determines our being determined to do something. -

Ontological status of ideasAn argument against Free Will

At 1pm exactly I have the idea to pick up a cup of coffee.

Assuming free will, at T seconds prior to 1pm, it hasn't been determined whether at 1pm I will have the idea to pick up the cup of coffee or not to pick up the cup of coffee.

Suppose T is 1 second. If it has been determined at 1 second before 1pm that I have the idea at 1pm to pick up the cup of coffee then this is no longer free will.

Suppose T is seconds. If it has been determined at second before 1pm that I have the idea at 1pm to pick up the cup of coffee then this is no longer free will.

"T" can be any number

Therefore, free will only applies if I choose between picking up the cup of coffee and not picking up the cup of coffee at 1pm exactly.

But this means that at 1pm I have two contradictory ideas in my mind at exactly the same time. But this is impossible, meaning that free will cannot be a valid theory.

I have seen evidence that a person can have two contradictory ideas consecutively, but I have never seen any evidence that a person can have two contradictory ideas at the same time.

===============================================================================

I don't see how this is relevant. — Metaphysician Undercover

Having an idea is not evidence for free will if ideas have been causally determined in a causally determined world.

===============================================================================

Then you do not accept my explanation. — Metaphysician Undercover

You have described a world where things obey the laws of nature, but I don't see where you have explained why things obey the laws of nature.

===============================================================================

Free will is not about the thoughts, it concerns the acts. — Metaphysician Undercover

I thought free will referred to our being free to have whatever thoughts we wanted

This sounds more like instinct, in that I look at a bright light and instinctively close my eyes.

===============================================================================

That's what choice and deliberation is all about, having contradictory thoughts at the same time. — Metaphysician Undercover

I agree that a person can have two contradictory thoughts consecutively, but it would be impossible for a person to have two contradictory thoughts contemporaneously.

===============================================================================

You are equally free to reach out for the coffee, or to not reach out for the coffee. You are free to choose. — Metaphysician Undercover

How do you know that we are free to choose?

How do you know that we don't live in a causally determined world, where our actions have been causally determined? -

Ontological status of ideasHaven't you seen parts of your body start to move without being acted on by an external force? If the "reason" for movement is an immaterial "idea", then this is evidence of free will. Isn't it? — Metaphysician Undercover

No. Suppose a person has the idea to reach out for a cup of coffee.

On the one hand, assuming free will, a person can have the idea to reach out for a cup of coffee. On the other hand, assuming there is no free will, a person can also have the idea to reach out for a cup of coffee.

Having an idea is nether evidence for or against free will.

===============================================================================

I was the one who used "law of nature" — Metaphysician Undercover

I have never said that I want you to be using the term "law of nature" in a different way.

My point has been that I don't accept that a law of nature precedes an event and makes things act the way they do.

===============================================================================A "law of nature" in this sense necessarily precedes the event, because the laws of nature are what makes things act the way that they do. — Metaphysician Undercover

The concept of "free will" does not involve self-causation. — Metaphysician Undercover

At 1pm a person has the thought to reach out for a cup of coffee.

Free will means that at 1pm that person could equally have had the thought not to reach out for the cup of coffee.

It is not possible to have two contradictory thoughts contemporaneously, both to reach out and not reach out.

One the one hand, free will is equally free have either of two contradictory thoughts, but on the other hand, free will is equally free to choose to act on one of these thoughts.

It seems that if free will is equally free to act on the thought of reaching out rather than not reaching out, then it is equally free to act of the thought of not reaching out as rather than reaching out.

If free to make any decision, then there would be no reason to make any decision, leading to the inability to be able to make any decision at all. -

Ontological status of ideasdemonstrate to me how introspection revealed to you that free will is an illusion, and you live in a deterministic world, — Metaphysician Undercover

I don't believe in particular that thoughts can cause themselves, and I don't believe in general in spontaneous self-causation.

One reason for my disbelief in spontaneous self-causation is that it is something I have never observed.

When I see a billiard ball on a billiard table start to move for no reason at all, then I may change my mind.

===============================================================================

No "reason why" is given for that law, it is stated as a descriptive fact — Metaphysician Undercover

Law of nature has more than one meaning.

It can be a description, as Newton's first law. From SEP - Laws of Nature

Science includes many principles at least once thought to be laws of nature: Newton’s law of gravitation, his three laws of motion, the ideal gas laws, Mendel’s laws, the laws of supply and demand, and so on.

It can be an explanation. As you wrote:

===============================================================================A "law of nature" in this sense necessarily precedes the event, because the laws of nature are what makes things act the way that they do. — Metaphysician Undercover

However, I see no reason to discuss them if they are just proposed as reason to accept the illogical premise of contemporaneousness. — Metaphysician Undercover

One of the reasons I don't believe in free will is that it requires self-causation, where the thought one has is contemporaneous with the decision to have the thought. -

Ontological status of ideasIsn't FREE WILL time based ? — Corvus

At exactly 1pm I decide to press the letter "T" on my keyboard. If free will is the case, at exactly 1pm, I could equally decide whether to press or not press the letter"T". But at exactly 1pm I did decide press the letter "T".

By the Law of Contradiction, free will cannot be the case, as it would result in a contradiction. At exactly 1pm I can't equally decide to press or not press the letter "T" and decide to press the letter "T" at the same time. -

Ontological status of ideasPersonally, I don't see too much point in discussing philosophy with someone who doesn't believe in free will. The entire discussion would then have to revolve around persuading the person that they have the power (free will) to change that belief. And this "persuading" would have to carry the force of a deterministic cause, to change that person's mind, which is contrary to the principles believed in by the person who believes in free will. This makes the task of convincing a person of the reality of free wil an exercise in futility. The only way that a person will come to believe in the reality of free will is through introspection, examination of one's own personal experiences. — Metaphysician Undercover

Free Will

A person hears an argument.

If that person has free will, then they are free to accept or reject the argument.

If that person has no free will, then it has been pre-determined whether they accept or reject the argument, and it is possible that they either accept or reject the argument.

Therefore, if I observe someone hearing an argument, my observing whether they accept or reject the argument is no guide as to whether or not they have free will.

Introspection

If a person has free will, through introspection they are free to reject the idea that they have free will, and conclude that they live in a deterministic world.

If a person has no free will, during introspection, it may have been pre-determined that they accept the idea that they have free will.

Introspection is no guide as to whether free will is an illusion or not.

===============================================================================

The Laws of Physics are the map (description), and the Laws of Nature are what is supposedly described by the map — Metaphysician Undercover

Two meanings of Law of Nature

It depends what you mean by "Law of Nature", because it has two possible interpretations.

Looking at Newton's First Law of Motion, possible meaning one is as a description, in that an object at rest will remain at rest until acted upon by an external force.

Possible meaning two is the reason why an object at rest will remain at rest until acted upon by an external force

I agree that there is a difference between a description of what happens and a reason why it happens

Looking at possible meaning two

Looking at why something happens, why an object will remain at rest until acted upon by an external force.

One question is, is the Law of Nature that an object remains at rest external and prior to the object or internal and contemporaneous with the object.

If this Law is external and prior to any particular object, and applies equally to all objects in space and time, then this raises the practical problem of where exactly does this Law exist?

If the Law is internal and contemporaneous within particular objects, and all objects in space and time follow the same Law, then this raises the practical problem as to why all these individual Laws, both spatially and temporally separate, are the same?

How exactly can there be a single Law of Nature that determines what happens to objects that are spatially and temporally separate? -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonAs per the OP section "Argument in defence of the PSR", logic (and the PSR) are first principles of metaphysics. This means they exist in all possibe worlds, which means they have necessary existence. Thus, logic and the PSR exist necessarily or inherently. This is an internal reason which is valid under the PSR. — A Christian Philosophy

There are many different type of logic, suggesting that no one logic exists necessarily. For example, there is Propositional Logic, First Order Logic, Second order logic , Higher order logic, Fuzzy logic, Modal logic, Intuitionistic Logic, Dialetheism, etc.

Logical systems also change, also suggesting that no one logical system is necessary. For example, today few would maintain that Aristotle's logic doesn't have serious limitations.

The Law of Identity "A is A" is one of the three Laws of Thought.

The Laws of Thought are axiomatic rules, taken to be true to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and argument. In other words, taken to be true but not necessarily true.

The Law of Identity was described as fundamental by Aristotle, as primitive by Leibniz and to a certain extent arbitrary by George Boole.

"A is A" exists as a convenient axiom, not as a necessity.

The PSR states that everything has a sufficient reason. It is true that we use the Law of Identity "A is A" for a reason, but this is an external reason, in that it is convenient for further reasoning and argument. This is not a "sufficient reason" in terms of the PSR

We use the Law of Identity as an axiom as a convenience not because it has any internal necessity.

The Law of Identity, as an example of logic, is used for the external reason that it is convenient in further reasoning, not from any reason of internal necessity. -

Ontological status of ideasYes, they have the freedom to do this. I don't believe that, do you? — Metaphysician Undercover

I think it is more likely that Free Will is an illusion than an actual thing.

===============================================================================

My usage was the latter sense of "laws of nature". — Metaphysician Undercover

In modern days we understand this as inductive reasoning, cause and effect, and laws of physics. This inclines us to think that these formulae are abstractions, the product of human minds, existing as ideas in human minds. And this is correct, but this way of thinking detracts from the need to consider some sort of "form" which preexists such events, and determines their nature. — Metaphysician Undercover

A "law of nature" in this sense necessarily precedes the event, because the laws of nature are what makes things act the way that they do. — Metaphysician Undercover

Laws of Nature

IE, you were referring to the Laws of Nature as "principles which govern the natural phenomena of the world" rather than "descriptions of the way the world is".

The question is, is it strictly true that "descriptions of the way the world is" are posterior to events and "principles which govern the natural phenomena of the world" are prior to events?

There is an overlap in Laws of Physics and Laws of Nature. For example, Newton's three laws of motion are described by the SEP article Laws of Nature as Laws of Nature and are described by the web site www.examples com as Laws of Physics.

By observing many times that the sun rises in the east, by inductive reasoning, I can propose the law that "the sun rises in the east". It is true that this law is posterior to my observations. But it is equally true that this law is prior to my observing the next sun rise.

When does a law become a Law of Nature?

If for hundreds of years hundreds of scientist have observed that F=ma, then this is sufficient for F=ma to become a Law of Nature.

But in principle the Law of Nature that F=ma is no different to my law that "the sun rises in the east", apart from the number of observations.

This Law of Nature is posterior to observations and prior to the next observation in exactly the same way that my law was posterior to my observations and prior to my next observation.

Whilst it is true that Laws of Nature are prior to the next event, they are also posterior to previous events.

The Law of Nature that F=ma is not the cause of the next event, it does not make the next event act as it does act and it does not determine the next event, but is a prediction about what the next event will be based on past experience.

Aristotle

Whereas for Plato Form is prior to physical things, for Aristotle's hylomorphic scheme, Form and Matter are intertwined. It may well be that Form is Matter, united by the Formal Cause.

As Form cannot exist independently of Matter, Form cannot exist prior to Matter but must be contemporaneous with it. -

Ontological status of ideasFree will allows a new, undetermined event to enter into the chain of causation determined by the past, at any moment in time. — Metaphysician Undercover

Some argue that Free Will is an illusion. -

Ontological status of ideasSince the prior forms are "idea-like" as immaterial, and the cause of things being the way that they are, in much the same way that human ideas cause artificial things to be the way that they are, through freely willed activities, we posit a divine mind, "God". — Metaphysician Undercover

The material and the immaterial

I can understand a God as being a prior cause to physical events, providing one accepts the possibility of a God.

I agree that human concepts can cause changes in the physical world, in that having the concept of thirst can cause a bottle of water in the world to move

The existence of Free Will is debated. Some argue that it is an illusion.

However, I don't agree that concepts in the mind and the Laws of Nature in a world outside the mind are immaterial, but rather that they are fully material.

As regards the particular Law of Nature that when there are regions of excess positive and negative charge within a cloud lightning occurs, there is nothing immaterial about this. The event is fully explainable as the deterministic behaviour of matter and forces between matter.

As regards concepts in the mind, as software exists within the hardware of a computer, concepts exist in the physical structure of the brain. If change the physical structure of the brain, then change the concepts within that physical structure.

No evidence has ever been presented of the dissociation of concepts from the brain, in that if a living brain moved from the living room to the dining room, no one would suggest the possibility of the concepts remaining in the living room.

IE, some may believe in God and Free Will, but it seems to me that they are not necessary as explanations of the relationship between mind and world outside the mind.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum