Comments

-

A -> not-A

A man posts a vague and somewhat mysterious advertisement for a job opening. Three applicants show up for interviews: a mathematician, an engineer, and a lawyer.

The mathematician is called in first. "I can't tell you much about the position before hiring you, I'm afraid. But I'll know if you're the right man for the job by your answer to one question: what is 2 + 2?" The mathematician nods his head vigorously, muttering "2 + 2, yes, hmm." He leans back and stares at the ceiling for a while, then abruptly stands and paces around a while staring at the floor. Eventually he stops, feels around in his pockets, finds a pencil and an envelope, and begins scribbling fiercely. He sits, unfolds the envelope so he can write on the other side and scribbles some more. Eventually he stops and stares at the paper for a while, then at last, he says, "I can't tell you its value, but I can show that it exists, and it's unique."

"Alright, that's fine. Thank you for your time. Would you please send in the next applicant on your way out." The engineer comes in, gets the same speech and the same question, what is 2 + 2? He nods vigorously, looking the man right in the eye, saying, "Yeah, tough one, good, okay." He pulls a laptop out of his bag. "This'll take a few minutes," he says, and begins typing. And indeed after just a few minutes, he says, "Okay, with only the information you've given me, I'll admit I'm hesitant to say. But the different ways I've tried to approximate this, including some really nifty Monte Carlo methods, are giving me results like 3.99982, 3.99991, 4.00038, and so on, everything clustered right around 4. It's gotta be 4."

"Interesting, well, good. Thank you for your time. I believe there's one last applicant, if you would kindly send him in." The lawyer gets the same speech, and the question, what is 2 + 2? He looks at the man for a moment before smiling broadly, leans over to take a cigar from the box on the man's desk. He lights it, and after a few puffs gestures his approval. He leans back in his chair, putting in his feet up on the man's desk as he blows smoke rings, then at last he looks at the man and says, "What do you want it to be?" — Srap Tasmaner -

A -> not-AI guess that' similar to the prisoner's dilemma. — TonesInDeepFreeze

It's related, yes.

consistency is defined in terms of consequence — TonesInDeepFreeze

Suppose I hold beliefs A and B. And suppose also that A → C, and B → ~C. That's grounds for claiming that A and B are inconsistent, but only because C and ~C are inconsistent. How would we define the bare inconsistency of C and ~C in terms of consequence?

Or did you have something else in mind?

Now it could be that the LNC, so beloved on this forum, functions as a minimal inconsistency guard, and from that you get the rest. ― This is a fairly common strategy with programming languages these days, to define a small subset of the language that's enough to compile the full language's interpreter or VM or whatever.

It could also be that the "starter versions" of consequence or consistency look a little different. I've been reading about some interesting work with gorillas, which suggests they grasp some "proto-logical" concepts. Negation, for example, is pretty abstract, but they seem to recognize and reason about rough opposites ― here/there, easy/hard, that sort of thing. Researchers have worked up a pretty impressive repertoire of "nearly logical" thinking among gorillas, though obviously their results are open to interpretation.

Anyway, suggests another type of bootstrapping.

( Might be worth mentioning that it looks like we're in the presence of one of Austin's trouser words, since the goal in Strawson's story is avoiding inconsistency, and that's what naturally came to mind above. ) -

A -> not-AWhat makes me hesitate to reduce logic to math has more to do with thinking about informal logic as still a part of logic, even though it doesn't behave in the same manner as formal logic — Moliere

If you wade through everything I've vomited here in the last day or so, I think you'll find me half backtracking on that ― although I still tend to think there's something like a "formal impulse" that you can scent underlying mathematics and logic, so perhaps even our informal reasoning. It's a very fog-enshrouded area.

It's already been mentioned a couple times in this thread that "follows from" is often taken as the core idea of logic, formal and informal. Logical consequence.

Another option is consistency, and it's the story that Peter Strawson tells (or told once, anyway) for the origins of logic: his idea was that if you can convince John that what he said is inconsistent, then he'll have to take it back, and no one wants to do that. So the core idea would be not whether one idea (or claim or whatever) follows from another, but whether two ideas (claims, etc) are consistent with each other. (I should dig out a quote. He tells it better than I do.)

Do you know about the ultimatum game? It's a standard experiment design in psychology, been done lots of times in all sorts of variations. You take pairs of subjects, and you offer one of them, say, $100, on this condition: they have to offer their partner a share; if the partner accepts the offer, they get the agreed upon amounts of money; if the partner refuses, they get nothing. ― Okay, I'm telling you that story (which you probably already know) because it's famous for completely undermining a standard assumption of rationality. Since the participants start with 0, the partner should be happy to get anything, to accept $1 out of $100, instead of walking away with nothing. But that's not what happens. The offers have to be fair, something close to 50-50. Not quite 50-50 is usually accepted, but lowball offers almost never are.

And the point is this: evidently, whether it's evolution or a cultural norm, we have a sense of fairness. And it can override what theory might say is rational. (The target here is Homo oeconomicus, the rational agent.)

Similarly, we might hunt for "logical consequence" or "consistency" as some sort of ur-concept upon which logic is built. -

A -> not-AI don't know of anyone who thinks natural language conveyance of mathematics is unimportant. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Fair. I was trying to convey the sense that there is this slightly annoying informal thing we have to do before we get on to doing math, properly, formally. And if you try to formalize that part ("We define a language L0, which contains the word 'Let', lower case letters, and the symbol '=', ..."), you'll find that you need in place some other formal system to legitimate that, and ― at some point we do have to just stop and figure out how to conceive of bootstrapping a formal system. And that bootstrapping will not be ex nihilo, but from the informal system ― if that's what it is ― that we are already immersed in, human culture, reasoning, language, blah blah blah.

I probably shouldn't have brought it up. It's another variation on the chicken-and-egg issue you pointed out.

Another way is to point to the coherency: There is credibility as both logic-to-math and math-to-logic are both intuitive and work in reverse nicely. — TonesInDeepFreeze

This is a nice point.

Circularity need not be vicious.*(I'm not thinking of the hermeneutic circle, though it has some pretty obvious applicability here.)

In particular, it's interesting to think of this whole complex of ideas as being "safe" because coherent ― you can jump on the merry-go-around anywhere at all, pick any starting point, and you will find that it works, and whatever you develop from the point where you began will serve, oddly, to secure the place where you started. And this will turn out to be true for multiple approaches to foundations for mathematics and logic.

Well that's just a somewhat flowery way of saying "bootstrapping" I guess.

Now I can't help but wonder if there's a way to theorize bootstrapping itself, but I am going to stop myself from immediately beginning to do that.

Thanks for very much for the conversation @TonesInDeepFreeze! -

A -> not-A

Just that there's at least here a dependence of mathematics on natural language, which gives the appearance of being purely pedagogical, or unimportant "set up" steps (still closely related to the thing about logical schemata, from above).

Algebra books set up problems this way, with a little bit of natural language, and then line after line of symbolism, of "actual" math.

If you get nervous about there being such a dependency, you might shunt it off to something you call "application".

I'm just wondering if the dependency is ever really overcome, especially considering the indefinability of "set" for example.

I keep throwing in more issues related to foundations, sorry about that. -

A -> not-Anatural language statements — fdrake

It's curious when you notice that mathematics textbooks have no alternative to saying things like "Let x = the number of oranges in the bag", and if you don't say things like that, you might as well not bother with the rest. (For similar reasons, doing it all in some APL-like symbolism would work, but no one would have any idea what the symbolism meant, if you didn't have "∈ means is a member of" somewhere.)

And if you have natural language, you have how humans live, human culture, evolution, and all the rest. There's your foundations. -

A -> not-AAbsolutely sure. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I'm okay with that.

The chicken and egg still bothers me, though, so one more point and one more question.

Another issue I have with treating logic as just "given" in toto, such that mathematics can put it to use, is that one of the central concepts of modern logic is nakedly mathematical in nature: quantifiers. If you rely on ∃ anywhere in constructing set theory (so that you can construct numbers), you're already relying on the concept of "at least one", which expresses both a magnitude and a comparison of magnitudes. Chicken and egg, indeed.

And if you need to identify the formula "∅ ⊂ ∅" as an instance of the schema "P → P", then you also have to have in place the apparatus of schemata and instances (those objects of Peter Smith's unforgiving gaze), which you presumably need both quantifiers and sets ― or at least classes of some kind ― to define rigorously. More chicken and egg.

And since we're wallowing in the muddy foundations*, a quick question: somewhere I picked up the idea that all you need to add to, say, classical logic is one more primitive, namely ∈, in order to start building mathematics. I suppose you need the concepts (but no definitions!) of member and collection as what goes on the LHS and RHS respectively, but that's it. And there just is no way around ∈, no way to cobble it together from the other logical constants. Is that your understanding as well? Or is there a better way to pick out what logic lacks that keeps it from functioning as itself the foundations of mathematics?(like those of Wright's Imperial Hotel)

What pretending? — TonesInDeepFreeze

Just a tendentious turn of phrase, not important.

Someplace to start writing without having to explain yourself. — fdrake

Kinda what I think. Also, at some point you'll have to say to the kiddies something like "group" or "collection" and just hope to God they know what you mean, because there is nothing anyone can say to explain it.

I think of mathematical logic sub-subject of formal logic. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Certainly. I almost posted the same observations about the dual existence of logic courses and research in academic departments (logic 101 in the philosophy department, advanced stuff in the math department, and so on).

― ― I suppose another way of putting the question about formal logic is whether we could get away with thinking of its use elsewhere, not only in the sciences, but in philosophy and the humanities, as, in essence, applied mathematics.

Set theory axiomatizes classical mathematics. And the language of set theory is used for much of non-classical mathematics That's one so what. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Sure sure, my point was to suggest that logic could live here too, and I'm really not sure why it doesn't. Set theory is needed for the rest of math and so is logic. There's your foundations, all in a box, instead of logic coming from outside mathematics ― that's what I was questioning, am questioning. (I suppose, as an alternative to reducing it to something acknowledged as being part of mathematics, which I admit doesn't seem doable.) -

A -> not-AWriters often used the word 'contained'; it is not wrong. But sometimes I see people being not clear whether it means 'member' or 'subset' — TonesInDeepFreeze

That's a solid point. It felt natural and intuitive when talking about "areas", subspaces of a partitioned probability space, and so on. But it's an awful word, as @Moliere proved. -

A -> not-A0 subset of 0 holds by P -> P. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I've granted that mathematics is dependent upon logic ― but, for the sake of argument, are you sure this is right?

That is, we need logic in place to prove theorems from axioms in set theory, to demonstrate that ∅⊂∅, for instance, but do we want to say it's because of the proof that it is so?

This close to the bone, I'm not sure how much we can meaningfully say, but something about "holds by" ― rather than, "is proved using" ― looks wrong to me.

Am I missing something obvious?

Peter Smith offers some nice content. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I used to enjoy reading his reviews of logic textbooks, because he was very picky about how they presented logic schemas and the process of "translating" natural language into P's and Q's. Unforgiving when authors were too slapdash or handwavy about this, which I thought showed good philosophical sense.

Oh, yes, the duals run all through mathematics. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Just the sort of thing, I understand, that motivates category theory.

#

Honestly, I'm not quite sure why formal logic (mathematical logic) isn't just considered part of mathematics. It would be part of foundations, to be sure, as set theory is, and you need it in place to bootstrap the rest, as you have to have sets (or an equivalent) to do much of anything in the rest of mathematics, but so what? What does mathematics get out of pretending it's importing logic from elsewhere? -

A -> not-Asubset v member — TonesInDeepFreeze

I should also have mentioned that it matters because ∅ has no members but ∅ ⊂ ∅ is still true, in keeping with how the material conditional works. -

A -> not-A

One other tiny point of unity: I always thought it was interesting that for "and" and "or" probability just directly borrows ∩ and ∪ from set theory. These are all the same algebra, in a sense, logic, set theory, probability. -

A -> not-AYour probability exploration is interesting. I think there's probably (pun intended) been a lot of work on it that you could find. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Indeed. I'd have to check, but I think Ramsey used to suggest that probability should be considered an extension of logic, "rather" (if that matters) than a branch of mathematics. It's an element of the "personalist" interpretation he pioneered and which de Finetti has probably contributed to the most. I'm still learning.

So, as far as I can tell, category theory does not eschew set theory but rather, and least to the extent of interpretability (different sense of 'interpretation' in this thread) it presupposes it and goes even further. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Yeah not clear to me at all. A glance at the wiki suggests there have been efforts to replace set theory entirely, but I'm a font of ignorance here.

On the other side, it did catch my eye when some years ago Peter Smith added an introduction to category theory to his site, Logic Matters. One of these days I'll have a look. -

A -> not-AP can be empty set, which is a member of every set. — Moliere

This is a correction ― not a member, but a subset.

A nitpick, for sure, but making exactly that distinction took a long time, and there were questions that remained very confusing until those concepts were clearly separated. -

A -> not-A

Yeah that's a funny thing. Mathematics cannot be reduced to logic, it turns out, but it appears to have an irremediable dependency on logic.

Sometimes it suggests to me that mathematics and logic are both aspects or expressions of some common root.

Anyway, much as I would like for probability to swallow logic, I'm resigned to mostly taking the sort of stuff I've been posting as a kind of heuristic, or maybe even a mathematical model of how logic works. (I have some de Finetti to read soon, so we'll see what he has to say.)

By the way, I understand the main focus for unifying math and logic in recent years has been in category theory, which I haven't touched at all. Is that something you've looked into? -

A -> not-A"is contained within", i.e. determined by — Moliere

Oh, not what I was saying at all.

The impetus for talking about this at all was the material conditional, and my suggestion was that you take P → Q as another way of saying that P ⊂ Q.

It helps me understand why false antecedents and true consequents behave the way they do.

Having gone that far, you might as well note that there are sets between ∅ and ⋃, and you can think of logic as a special case of the probability calculus.

That's how it works in my head. YMMV -

A -> not-AThe (probability) space of A is entirely contained within the (probability) space of not-A.

Well, of course it is. That's almost a restatement of the probability of P v ~P equals 1. — Moliere

?

A and its complement ~A are disjoint. If A is contained in ~A, it must be ∅. -

A -> not-Ayour reduction of material implication to set theory. I'm not sure how to understand that, really — Moliere

It's not that complicated.

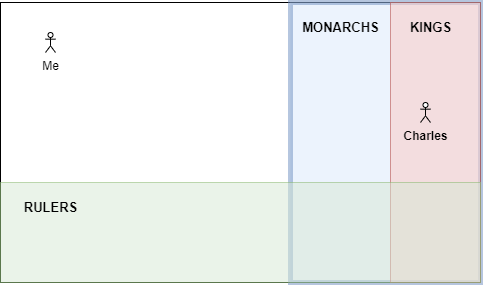

The whole space is people, say. Some are rulers, some monarchs, some kings, some none of those. A lot of monarchs these days are figureheads, so there's only overlap with rulers. All kings are monarchs, but not all monarchs are kings.

There are some things you can say about the probability of a person being whatever, and the ones we're interested in would be like this:

-

Pr(x is a monarch | x is a king) = 1

That is, the probability that x is a monarch, given that x is a king, is 1. The space of "being a king" is entirely contained in the space of "being a monarch".

-

King(x) → Monarch(x)

Similarly we can say

-

Pr(x is not a king | x is not a monarch) = 1

which is the contrapositive.

The complement of Monarchs is contained in the complement of Kings, but the latter also contains Queens and I don't know, Czars and whatnot. Not a king doesn't entail not a monarch, and sure enough Pr(x is a monarch | x is not a king) > 0.

Conceptually, that's it. (There are some complications, one of which we'll get to.)

I find the visualization helpful. We're just doing Venn diagram stuff here.

if the moon is made of green cheese then 2 + 2 = 4. That's the paradox, and we have to accept that the implication is true. How is it that the empirical falsehood, which seems to rely upon probablity rather than deductive inference, is contained in "2 + 2 = 4"? — Moliere

For this example, there's a couple things we could say.

Say you partition a space so that 0.000001% of it represents (G) the moon being made of green cheese, and the complement ― 99.999999% ― is it not (~G). Cool. Little sliver of a possibility over to one side.

2 + 2 = 4 is true for the entire space, both G and ~G. Both are contained in the space in which 2 + 2 = 4, which will keep happening whatever your empirical proposition because it's, you know, a necessary truth.

What's slightly harder to express is something we take to be necessarily false, like 2 + 2 = 5. The space in which that's true is empty, and the empty set is a subset of every single set, including both G and ~G. It could "be" anywhere, everywhere, or nowhere, doing nothing, not taking up any room at all. It doesn't have a specifiable "location" because Pr(2 + 2 = 5 | E) = 0 for any proposition E at all.

Both necessary truths and necessary falsehoods fail to have informative relations with empirical facts. -

A -> not-Avalidity is about deducibility — Leontiskos

I don't even need to advert to real-world cases — Leontiskos

Well, the thing is, deducibility is for math and not much else. That's the point of my story about George, and my general view that logic is ― kinda anyway ― a special case of the probability calculus.

an argument is supposed to answer the "why" of a conclusion — Leontiskos

I agree with this in spirit, I absolutely do. I frequently use the analogy of good proofs and bad proofs in mathematics: both show that the conclusion is true, but a good proof shows why.

I'll add another point: when you say something another does not know to be false but that they are disinclined to believe, they will ask, "How do you know?" You are then supposed to provide support or evidence for what you are saying.

The support relation is also notoriously tricky to formalize (given a world full of non-black non-ravens), so there's a lot to say about that. For us, there is logic woven into it though:

-

"Billy's not at work today."

"How do you know?"

"I saw him at the pharmacy, waiting for a prescription."

It goes without saying that Billy can't be in two places at once. Is that a question of logic or physics (or even biology)? What's more, the story of why Billy isn't at work should cross paths with the story of how I know he isn't. ("What were you doing at the pharmacy?")

As attached as I've become, in a dilettante-ish way, to the centrality of probability, I'm beginning to suspect a good story (or "narrative" as @Isaac would have said) is what we are really looking for. -

A -> not-AI encourage respectful discussion of these topics by all parties. — NotAristotle

Good lad.

I have learned — NotAristotle

Even better. -

A -> not-Aa notion of "follows from," — Leontiskos

I sympathize. I think a lot of our judgments rely on what I believe @Count Timothy von Icarus mentioned earlier under the (now somewhat unfortunate) heading "material logic", distinguished from formal logic.

A classic example is color exclusion.

When you judge that if the ball is red then it's not white ― well, to most people that feels a little more like a logical point than, say, something you learn empirically, as if you might find one day that things can be two different colors. (Insert whatever ceteris paribus you need to.)

Wittgenstein would no doubt say this comes down to understanding the grammar of color terms. (He talked about color on and off for decades, right up until the end of his life.)

Well, what do we say here ― leaving aside whether color exclusion is a tenable example? What you're after is a more robust relationship between premises and conclusions, something more like grasping why it being the case that P, in the real world, brings about Q being the case, in the real world, and then just representing that as 'P ⇒ Q' or whatever. Not just a matter of truth-values, but of an intimate connection between the conditions that 'P' and 'Q' are used to represent. Yes? -

A -> not-Areductio? — Leontiskos

I'm taking this out of context, for the sake of a comment.

I'm a little rusty on natural deduction but I think reductio is usually like this:

-

A (assumption)*

...

B (derived)

...

~B (derived)

⊥

━━━━━━━━━━━━

A → ⊥ (→ intro)*

━━━━━━━━━━━━

~A (~ intro)

Not sure how to handle the introduction of ⊥ but it's obviously right, and then our assumption A is discharged in the next line, which happens to be the definition of "~" or the introduction rule for "~" as you like.

Point being A is gone by the time we get to ~A. It might look like the next step could very well be A → ~A by →-introduction, but it can't be because the A is no longer available.

What you do have is a construction of ~A with no undischarged assumptions.

#

We've talked regularly in this thread about how A → ~A can be reduced to ~A; they are materially equivalent. We haven't talked much about going the other way.

That is, if you believe that ~A, then you ought to believe that A → ~A.

In fact, you ought to believe that B → ~A for any B, and that A → C for any C.

And in particular, you ought to believe that

-

P → ~A (where B = P)

~P → ~A (where B = ~P);

and you ought to believe that

-

A → Q (where C = Q)

A → ~Q (where C = ~Q).

If you combine the first two, you have

-

⊤ → ~A

while, if you combine the second two, you have

-

A → ⊥.

These are all just other ways of saying ~A.

#

Why should it work this way? Why should we allow ourselves to make claims about the implication that holds between a given proposition, which we take to be true or take to be false, and any arbitrary proposition, and even the pair of a proposition and its negation?

An intuitive defense of the material conditional, and then not.

"If ... then ..." is a terrible reading of "→", everyone knows that. "... only if ..." is a little better. But I don't read "→" anything like this. In my head, when I see

-

P → Q

I think

-

The (probability) space of P is entirely contained within the (probability) space of Q, and may even be coextensive with it.

The relation here is really ⊂, the subset relation, "... is contained in ...", which is why it is particularly mysterious that another symbol for → is '⊃'.

The space of a false proposition is nil, and ∅ is a subset of every set, so ∅ → ... is true for everything.

The complement of ∅ is the whole universe, unfortunately, and that's what true propositions are coextensive with. When you take up the whole universe, everything is a subset of you, which is why ... → P holds for everything, if P is true.

Most things are somewhere between ∅ and ⋃, though, which is why I have 'probability' in parentheses up there.

The one time he did — Moliere

Which is the interesting point here.

-

"George never opens when he's supposed to."

"Actually, there was that one time, year before last ― "

"You know what I mean."

Ask yourself this: would "George will not open tomorrow" be a good inference? And we all know the answer: deductively, no, not at all; inductively, maybe, maybe not. But it's still a good bet, and you'll make more money than you lose if you always bet against George showing up, if you can find anyone to take the other side.

"George shows up" may be a non-empty set, but it is a negligible subset of "George is scheduled to open", so the complement of "George shows up" within "George is scheduled", is nearly coextensive with "George is scheduled". That is, the probability that any given instance of "George is scheduled" falls within "George does not show up" is very high.

TL;DR. If you think of the material conditional as a containment relation, its behavior makes sense.

((Where it is counterintuitive, especially in the propositional calculus, it's because it seems the only sets are ∅ and ⋃. Even without considering the whole world of probabilities in fly-over country between 0 and 1 ― which I think is the smart thing to do ― this is less of a temptation with the predicate calculus. In either case, the solution is to think of the universe as being continually trimmed down to one side of a partition, conditional-probability style.)) -

A -> not-AWhat does footnote 11 say? Because the whole dispute rides on that single word, "whenever." — Leontiskos

Here, "whenever" is used as an informal abbreviation "for every assignment of values to the free variables in the judgment" — same

Actually I expected the footnote just to be a reference to Gentzen, but it was glossed! -

A -> not-AI mean your post does use two different operators? — Michael

Yes that's probably necessary, but something I overlooked.

Here's the sort of thing I was trying to remember. It's Gentzen's stuff.

The standard semantics of a judgment in natural deduction is that it asserts that whenever[11] A 1 , A 2 , etc., are all true, B will also be true. The judgments

A 1 , … , A n ⊢ B

and

⊢ ( A 1 ∧ ⋯ ∧ A n ) → B

are equivalent in the strong sense that a proof of either one may be extended to a proof of the other. — wiki

And similarly

The sequents

A 1 , … , A n ⊢ B 1 , … , B k

and

⊢ ( A 1 ∧ ⋯ ∧ A n ) → ( B 1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ B k )

are equivalent in the strong sense that a proof of either sequent may be extended to a proof of the other sequent. — same

What I forgot is that you move the turnstile ⊢ to the left of the whole formula, with an empty LHS.

So the result I was trying to remember was probably just cut-elimination. I never got very far in my study of Gentzen, so the best I can usually do is gesture over-confidently in his direction. -

A -> not-ATones is interpreting English-language definitions of validity according to the material conditional — Leontiskos

Is this what you mean:

'Validity' is being defined as a concept that applies to arguments which have the form

when it should be defined for some other relation than →, because → does not properly capture the root intuition of logical consequence, or "... follows from ...", or whatever.

There are a couple issues here, I think.

One is at least somewhat technical, and I hope @TonesInDeepFreeze can figure out what I'm trying to remember. There is a reason we don't need an additional implication operator ― that is, one that might appear in a premise, say, and another for when we make an inference. In natural deduction systems, if you assume A and then eventually derive B, you may discharge the assumption by writing 'A → B'; this is just the introduction rule for →, and it is exactly the same as the '→' that might appear in a premise.

Thus the form for an argument above is, I believe, exactly the same as writing this:

That is, we lose nothing by treating an argument as a single material implication, the premises all and-ed together on the LHS and the conclusion on the RHS. (And I could swear there's an important theorem to this effect.)

the material conditional and the consequence relation do not operate in the same way — Leontiskos

Okay, so yeah, this is what you were saying, but in formal logic identifying the consequence relation with material implication is not an assumption or a mistake but a result. I believe. Hoping @TonesInDeepFreeze knows what I'm talking about. -

A -> not-Athese mean two different things:

1. A → ¬A

2. A → (A ∧ ¬A) — Michael

You might want to double-check that.

Tones' is literally applying the material conditional as an interpretation of English language conditionals — Leontiskos

Actually, he isn't. The OP's question was not about ordinary English at all:

1. A -> not-A

2. A

Therefore,

3. not-A.

Is this argument valid? Why or why not? — NotAristotle

I mainly use formal logic for analysing ordinary language arguments, so that's what I've been thinking about, but the original question was not about that.

This shouldn't be about choosing sides. -

A -> not-A

"George is opening tomorrow, and we all know what that means."

"George isn't opening tomorrow."

The conditional here is actually true, because George never opens. -

A -> not-AI'm not sure what post you are responding to — Leontiskos

None, or .

Just trying to think of real world examples of a formula like "A → ~A", likely dressed up enough to be hard to spot. Excluding reductio, where the intent is to derive this form. What I want is an example where this conditional is actually false, but is relied upon as a sneaky way of just asserting ~A.

I suppose accusations of hypocrisy are nearby. "Your anti-racism is itself a form of racism." "Your anti-capitalism materially benefits you." "Your piety is actually vanity." Generalize those and instead of saying, hey here's a case where the claim is A but it's really ~A, you say, every A turns out to be ~A. Now it's a rule.

Still thinking.

The move is always to a meta-level. What is the game? What is the competition? What is logic? Our world has a remarkable tendency to try to avoid those questions altogether, usually for despair of finding an answer. — Leontiskos

With good reason, as you well know. -

A -> not-Aan actual example — TonesInDeepFreeze

I agree with all that. The toy examples we're dealing with here are too transparent for anyone to get away with much. -

A -> not-ATrivial — frank

Feynman had a party trick he used to do, I think in grad school. He could tell whether any mathematical conjecture was true.

What he would do is imagine the conditions concretely, in his mind. Like start with a tennis ball to represent some object; then a condition would be added, and he'd need some explanation of what it means, to know whether to paint the entire ball purple, or half, or maybe add spots or something. He would follow the explanations making changes to his imaginary object and then when asked, is it X?, he could check and see.

But the trick is this: when he got one wrong and the math students explained why, he would say, "Oh, then it's trivial!" which to the mathematicians was always completely satisfying. -

A -> not-A@Count Timothy von Icarus

Still hunting for a solid example, but in the meantime there's

-

(1) You only won because you cheated.

The sequence from here is most likely

-

(2) So you admit I won.

-

(3) It's not a proper game if you cheated.

And then the argument shifts from whether I got more points than you (or whatever) to whether the rules were followed.

But "the rules" can be surprising. Casinos universally have a rule against "card counting," which amounts to a rule against being too good at playing cards.

Sometimes among children using greater skill or knowledge is treated as cheating. It's clear they have an intuition about what fair competition is, but they mistakenly treat every advantage as unfair, or every unfair advantage as cheating.

What's happening here, broadly, is that the competition continues "by other means." The losing party, in one sense, grants that they lost, but continues in the competitive spirit, which means they have to shift ground from whether they "officially" or "technically" lost to whether that was a "real" loss, or whether there had a been a "real" competition in the first place.

So we have two versions here:

-

(4) If you won because you cheated, then you didn't win.

(5) If you "won" because I cheated, then you lost. -

A -> not-A'degenerate' in a non-pejorative sense as often in mathematics — TonesInDeepFreeze

Yes, that was my meaning, as with the boat example. I think, though, we can allow a somewhat negative connotation because reliance in argumentation on degenerate cases is often inadvertent or deceptive. "There are a number of people voting for me for President on Tuesday [and that number happens to be 0]."

importance in Boolean logic used along the way in switching theory, computation, etc. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Absolutely. I mentioned automated reasoning projects when you need classical logic in full generality with P → P and all. Of course.

But that is not the only sort of application of logic, and as I noted reducing someone's argument to P → P is pointing out that they are "begging the question," generally considered a fatal problem for an argument. That conditional is legitimate in form, and is generally a theorem, but it is fatal if relied on to make a substantive point or demonstrate a claim. It will only happen inadvertently ― in which case, a good-faith discussant will admit their error ― or with an intent to mislead by sophistry.

Logic is a vast field of study, including all kinds of formal and informal contexts. I would not so sweepingly declare certain formulations otiose merely because one is not personally aware of its uses. — TonesInDeepFreeze

A fair point. Let's say, I'm only pointing out forms, or uses of particular schemata, that might raise our suspicions. "Heads I win, tails you lose" may in some cases demonstrate that I'm necessarily right and you necessarily wrong. Hurray! But in some cases it might amount to me stacking the deck against you.

Fundamentally, all we're talking about in this case is arguing from a set a premises which are inconsistent ― in fact, here, necessarily inconsistent. As I keep saying, that's either inadvertent or deceptive. Very often on this forum people attempt to show that a set of premises is inconsistent precisely by making correct inferences that make the inconsistency obvious. But people arguing from inconsistent premises often make inferences that, while in themselves correct, continue to hide their inconsistency. (Sometimes this is because not all premises are explicitly stated, and the inconsistency is in what is "assumed".) In such cases, it is not uncommon for people to insist on the correctness of their inferences. But it's not validity we usually disagree over, but soundness, and inconsistent premises make valid inferences unsound.

None of this news to you, I'm sure. -

A -> not-AI don't see how it would not be natural to take you as first claiming that my remarks were non-cooperative and abusive. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Agreed, a natural reading, but my target was really someone who might present an argument in the OP's schema, as a perfectly respectable modus ponens. It's MP alright, but it's a degenerate case.

Similarly for the disjunction. My point was that disjunctions that amount to "heads I win, tails you lose" are disjunctive in form only, and we expect something more substantive.

In short, no attack was intended on you or any other poster, but only on the illicit use someone might make of legitimate argument form. To the extent that I was offering criticism, it was to say that we are not helpless when confronted with correct inference in form only, and can choose to block such deviant uses if we like.

And we can leave formal logic alone, as a study in its own right, but not import it wholesale when all we really need is the convenience of schematizing arguments.

A related example would be various attempts to deal with what many people find counterintuitive about the material conditional. There are several ways to block troublesome cases.

Hence my casual suggestion that we have very little practical use for "If grass is green then grass is green" or "If grass is green then grass is not green." -

A -> not-Aopprobrium — TonesInDeepFreeze

I'll just say that no opprobrium was intended. I too have gained, I believe, from my study of logic and mathematics, and I have found formal methods intensely interesting, so neither am I disparaging that as an interest.

Some people are interested in formal logic full-stop. Some people are only interested in formal logic as a help meet to argumentation and analysis. For the latter, results about logic ― the completeness theorems and such ― are not only of less interest, but less everyday use. All I was saying.

Nor was I accusing you or the original poster, or anyone in this thread, of engaging in sophistry, if that's what you thought. Maybe it seemed to you I was engaging in the current controversy on the other side, but I was not. You are, of course, correct about the formal question.

I was looking at the argument schema presented in the OP. If you imagine this as the formal representation of a substantive argument, you would have to have serious doubts about what was going on in that argument. This was the "veneer" of logic I was talking about. Any argument that could be formalized in the schema presented would instantiate an accepted form in a deeply questionable way. Hence "sophistry". That wasn't intended to refer to you, to your explanations, to anyone in this thread, but to a hypothetical argument that would fit the schema under discussion. ― You'll note that @TonesInDeepFreeze and I were trying to think of a genuine example of such an argument, and I'll now be getting back to that.

I hope my "position" is clearer now. -

A -> not-Acan you demonstrate that the resulting calculus will be complete? — Banno

If you are interested in the basics of ordinary formal logic, then it would be a question that would naturally occur to you. But I don't see why you couldn't study other branches of philosophy without understanding the completeness of the propositional calculus. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Quite. I worked through some of the usual metatheorems years ago when I was studying formal logic. If you're interested in the properties of these formal systems, such results are just what you're interested in. And I'm sure there are issues that come up in philosophy that depend substantively on such results.

But for the everyday use of logic just to schematize and clarify arguments, you get a lot more mileage out of de Morgan's laws, contrapositives, a solid understanding of quantifiers, and such. The cash value of completeness for such applications is nil.

Can you prove A→A, for example? — Banno

As Tones suggested, it might be necessary for proving certain metatheorems, but of course in real applications of logic ― such as on TPF ― "A→A" usually only appears as an accusation of question-begging. It's not something anyone would have any reason to argue for, and it's not a premise anyone would intentionally rely on. ― Hence my suggestion that we could usually get along without it.

But what do you mean by 'abusive'? — TonesInDeepFreeze

The basic idea is "formally correct but misleading". Akin to sophistry. Or to non-cooperative implicature, like saying "Everyone on the boat is okay" when it's only true because no one is left on the boat and all the dead and injured are in the water.

In this case, for instance, it is suggested that we conclude ~A by modus ponens. The form is indeed instantiated ― I'm not contesting that ― but the first premise is materially equivalent to ~A. People worry over the sense in which the conclusion of a deductive argument is "contained" in the premises ― here it is one of the premises. Who needed modus ponens?

(Besides, you are effectively arguing from the set {A, ~A}. You could as well conclude A from that ― or any B you like ― so in what sense should this count as a "demonstration" that ~A? In what sense is the relationship of A and ~A revealed or clarified? It may be modus ponens in form, but hardly in spirit.)

And if we step back and look at the offending premise, we get to ~A by noting that A→~A is materially equivalent to ~A v ~A. Now what kind of disjunction is that? It's a well-formed-formula ― no one can deny that ― but it's hardly what we usually have in mind as a disjunction. It's "heads I win, tails you lose." That's abusive.

There is, in this case, a veneer of logic over what could scarcely be considered rational argumentation. If this appearance of rationality serves any purpose, it must be to mislead, hence abusive, eristic, sophistical, non-cooperative. ― Again, I am only talking about how logic is used as an aid to ordinary philosophizing, not what people get up to in a logic lab. -

A -> not-AWell for a start you would no longer be dealing with a complete version of propositional calculus... — Banno

1. Meaning what exactly?

2. Is the answer to (1) something I should care about?

Do you, Srap, agree that the argument in the OP is valid? — Banno

I don't really care. It's abusive.

I cannot think of a way to frame this as a real example — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'll come up with one. I think you see it around the forum and elsewhere in the wild pretty regularly. Informally, we're looking for a case where you try to disagree with me, but that attempt misfires because in stating your position you have to tacitly agree with me.

So you claim A, but I show that still leads, by some chain of reasoning or argument to my claim ~A. Introducing A⊃~A is just icing on the cake, because it's still just an extravagant way of saying ~A. -

A -> not-AIt seems folk think A → ~A is a contradiction. It isn't. — Banno

But (A->~A) & A is a contradiction.

If you assert A->~A, and then go on to assert A, then you have contradicted yourself.

The set {A->~A, A} is not a contradiction because it is not a formula, but a set. It is, however, inconsistent.

Would there be any harm in requiring that the conditional in a modus ponens have fresh variables on the right hand side? We would lose, in effect, only this one and A->A, which is either useless or the LEM, and thus innocent or tendentious, depending on how you look at it.

I mean, mathematicians always prefer the greatest generality, at the minor, to them, cost of letting in the degenerate case. If your project is automated reasoning, you'll go with the usual. But for doing philosophy, we don't have to let the mathematicians have the last word.

If the only question here is "How does formal logic work?" we know the answer to that. But around here we're more interested in the practical use of logic, and it seems to me letting mathematical logic have the last word is the tail wagging the dog.

Only line 1 is not, ~A. It's A→~A. — Banno

I mean, I get that MP requires a "->", but (A->~A)<->~A, so I'm puzzled by insisting on this nicety. In classical logic it's materially equivalent to the disjunctive syllogism, isn't it?

Srap Tasmaner

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum