Comments

-

PerceptionI'm sure you will be able to explain your account without sending us off to such a text. — Banno

I don't have an account because I'm not a physicist or neuroscientist. As I have repeatedly said, perception cannot be explained by armchair philosophy.

But of course pain and colour are quite different. — Banno

Only in that they are caused by quite different brain activity.

Tomatoes, strawberries and radishes really have the distinctive property that they do appear to have. They are red. — Banno

You're equivocating.

If we take dispositionalism as an example then "the tomato is red" means "the tomato is disposed to look red". The word "red" in the phrase "looks red" does not prima facie refer to a property of the tomato, and so it does not prima facie follow from "the tomato is disposed to look red" that the tomato has the distinctive property that it appears to have.

So what do you mean by "the tomato is red"? Without further explanation your claim here is a non sequitur. -

PerceptionYep. So you have not explained red by equating it with a red percept. — Banno

What are you talking about? Your obsession with language is leading you to nonsense. It's incredibly simple for anyone who isn't blinded by Wittgenstein.

Pain is a percept, red is a percept. That's it. If you don't understand what pain percepts are then read some neuroscience and stab yourself in the foot. -

Perception

You're asking me which percepts the word "red" refers to. I can only answer such a question by using a word that refers to these percepts, and given that there is no appropriate synonym for "red", all I can do is reuse the word "red".

The word "pain" refers to pain, the word "red" refers to red, the word "sour" refers to sour.

There's nothing "viciously circular" about this. -

Perception

The red percepts are red, the pain percepts are pain. These questions are tiresome, so if it's all you can resort to then I'm going to end it here. -

PerceptionSo which ones are red? Only the red ones? — Banno

This isn't difficult Banno. If you understand what it means for pain to be a percept then you understand what it means for red to be a percept. If you don't understand what it means for pain to be a percept then I can't help you. -

Perception

There are lots of percepts, many of the same type. Every pain is a percept, every pleasure is a percept, every sour is a percept, every red is a percept. -

PerceptionYou want to equate the colour red with a thing you call a red mental percept. But they are not the very same thing. — Banno

Yes they are. -

PerceptionIt is very unclear what a 'mental percept" is, when you take it out of the context of the scientific papers that use it. — Banno

And? It's unclear what electrons are when you take them out of the context of the scientific papers that talk about them. -

PerceptionWhat is rejected is the assertion that red is nothing but a 'mental percept' — Banno

I haven't claimed that. I have only claimed that the red mental percept is our ordinary, everyday understanding of red (even if we do not understand that it is a mental percept). -

Perceptionthe science is wrong. — Banno

Well, if you're just going to dismiss the scientific evidence because it disagrees with Wittgenstein's nonsense story about a beetle then we're never going to agree.

I'm going to trust the science, not armchair philosophy, when it comes to explaining how perception works. You do you. -

PerceptionThey really have the distinctive property that they appear to. — Banno

The science proves otherwise. They have a surface layer of atoms that reflect various wavelengths of light, but no colour, because colour is something else entirely. -

PerceptionNotice no mental percepts needed — Richard B

Of course they are, else you wouldn't be seeing anything; you'd just have light reaching your eyes and then nothing happening, e.g. blindness or blindsight. -

PerceptionThe tomatoes are red. — Banno

The question isn't "are tomatoes red?". The question is "do objects like tomatoes, strawberries and radishes really have the distinctive property that they do appear to have?"

You have admitted before that colour terminology is used in more than one way, and I have agreed. The problem is that you are then using this to equivocate. Any meaning of the word "red" or the sentence "the tomato is red" that does not concern the tomato's appearance is irrelevant. And any meaning of the word "red" or the sentence "the tomato is red" that does concern the tomato's appearance is explained by physics and neuroscience, specifically showing that tomatoes do not have such a property. -

PerceptionClaiming that they do not "really" have these colours is a misunderstanding of the nature of colour. — Banno

No, claiming that they really have these colours is a misunderstanding of the nature of colour.

Vision science: Photons to phenomenology:

People universally believe that objects look colored because they are colored, just as we experience them. The sky looks blue because it is blue, grass looks green because it is green, and blood looks red because it is red. As surprising as it may seem, these beliefs are fundamentally mistaken. Neither objects nor lights are actually “colored” in anything like the way we experience them. Rather, color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights. The colors we see are based on physical properties of objects and lights that cause us to see them as colored, to be sure, but these physical properties are different in important ways from the colors we perceive.

Color:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess. Oceans and skies are not blue in the way that we naively think, nor are apples red (nor green). Colors of that kind, it is believed, have no place in the physical account of the world that has developed from the sixteenth century to this century.

Not only does the scientific mainstream tradition conflict with the common-sense understanding of color in this way, but as well, the scientific tradition contains a very counter-intuitive conception of color. There is, to illustrate, the celebrated remark by David Hume:

"Sounds, colors, heat and cold, according to modern philosophy are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind." (Hume 1738: Bk III, part I, Sect. 1 [1911: 177]; Bk I, IV, IV [1911: 216])

Physicists who have subscribed to this doctrine include the luminaries: Galileo, Boyle, Descartes, Newton, Thomas Young, Maxwell and Hermann von Helmholtz. Maxwell, for example, wrote:

"It seems almost a truism to say that color is a sensation; and yet Young, by honestly recognizing this elementary truth, established the first consistent theory of color." (Maxwell 1871: 13 [1970: 75])

This combination of eliminativism—the view that physical objects do not have colors, at least in a crucial sense—and subjectivism—the view that color is a subjective quality—is not merely of historical interest. It is held by many contemporary experts and authorities on color, e.g., Zeki 1983, Land 1983, and Kuehni 1997.

Neural representations of perceptual color experience in the human ventral visual pathway:

There is no color in light. Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus. This distinction is critical for understanding neural representations, which must transition from a representation of a physical retinal image to a mental construct for what we see. Here, we dissociated the physical stimulus from the color seen by using an approach that causes changes in color without altering the light stimulus. We found a transition from a neural representation for retinal light stimulation, in early stages of the visual pathway (V1 and V2), to a representation corresponding to the color experienced at higher levels (V4 and VO1).

Opticks:

The homogeneal Light and Rays which appear red, or rather make Objects appear so, I call Rubrifick or Red-making; those which make Objects appear yellow, green, blue, and violet, I call Yellow-making, Green-making, Blue-making, Violet-making, and so of the rest. And if at any time I speak of Light and Rays as coloured or endued with Colours, I would be understood to speak not philosophically and properly, but grossly, and accordingly to such Conceptions as vulgar People in seeing all these Experiments would be apt to frame. For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour. -

PerceptionYou are taking the special case in which for the purposes of experiment researchers restrict "seeing red" to having a "mental percept of red" and taking this to be what "seeing red' is in every other case. — Banno

I'm not. I'm saying that our everyday, ordinary conception of colours is that of sui generis, simple, qualitative, sensuous, intrinsic, irreducible properties, not micro-structural properties or reflectances, and that these sui generis properties are not mind-independent properties of tomatoes, as the naive colour realist believes, but mental percepts caused by neural activity in the brain, much like smells and tastes and pain.

The relevant question "do objects like tomatoes, strawberries and radishes really have the distinctive property that they do appear to have?" is not answered by engaging in a linguistic analysis of all the ways that the word "red" or the phrase “seeing red” are used, and so your continued insistent to appeal to language is a fundamentally flawed approach to the problem. The only people who can answer the question are physicists and neuroscientists. Armchair philosophy is useless in this situation. -

PerceptionYou're contradicting yourself at nearly every turn, in addition to the fact that your 'argument' leads to the absurdity of you claiming out loud, for everyone to see, that you do not conclude anything about stimulus from your experience all the while insisting that there is no color in stimulus. — creativesoul

I'm reporting what the science says.

Opticks:

The homogeneal Light and Rays which appear red, or rather make Objects appear so, I call Rubrifick or Red-making; those which make Objects appear yellow, green, blue, and violet, I call Yellow-making, Green-making, Blue-making, Violet-making, and so of the rest. And if at any time I speak of Light and Rays as coloured or endued with Colours, I would be understood to speak not philosophically and properly, but grossly, and accordingly to such Conceptions as vulgar People in seeing all these Experiments would be apt to frame. For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour.

Neural representations of perceptual color experience in the human ventral visual pathway:

There is no color in light. Color is in the perceiver, not the physical stimulus. This distinction is critical for understanding neural representations, which must transition from a representation of a physical retinal image to a mental construct for what we see. Here, we dissociated the physical stimulus from the color seen by using an approach that causes changes in color without altering the light stimulus. We found a transition from a neural representation for retinal light stimulation, in early stages of the visual pathway (V1 and V2), to a representation corresponding to the color experienced at higher levels (V4 and VO1).

Vision science: Photons to phenomenology:

People universally believe that objects look colored because they are colored, just as we experience them. The sky looks blue because it is blue, grass looks green because it is green, and blood looks red because it is red. As surprising as it may seem, these beliefs are fundamentally mistaken. Neither objects nor lights are actually “colored” in anything like the way we experience them. Rather, color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights. The colors we see are based on physical properties of objects and lights that cause us to see them as colored, to be sure, but these physical properties are different in important ways from the colors we perceive.

Color:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess. Oceans and skies are not blue in the way that we naively think, nor are apples red (nor green). Colors of that kind, it is believed, have no place in the physical account of the world that has developed from the sixteenth century to this century.

Not only does the scientific mainstream tradition conflict with the common-sense understanding of color in this way, but as well, the scientific tradition contains a very counter-intuitive conception of color. There is, to illustrate, the celebrated remark by David Hume:

"Sounds, colors, heat and cold, according to modern philosophy are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind." (Hume 1738: Bk III, part I, Sect. 1 [1911: 177]; Bk I, IV, IV [1911: 216])

Physicists who have subscribed to this doctrine include the luminaries: Galileo, Boyle, Descartes, Newton, Thomas Young, Maxwell and Hermann von Helmholtz. Maxwell, for example, wrote:

"It seems almost a truism to say that color is a sensation; and yet Young, by honestly recognizing this elementary truth, established the first consistent theory of color." (Maxwell 1871: 13 [1970: 75])

This combination of eliminativism—the view that physical objects do not have colors, at least in a crucial sense—and subjectivism—the view that color is a subjective quality—is not merely of historical interest. It is held by many contemporary experts and authorities on color, e.g., Zeki 1983, Land 1983, and Kuehni 1997. -

PerceptionAnd yet... you and Michael are doing exactly that. — creativesoul

I'm not concluding anything from my experience. I am telling you what physics and neuroscience have determined. I accept what the scientists say about the way the world works, not what some armchair philosopher says. -

PerceptionAre there colorless rainbows? — creativesoul

I responded to this above. If Newton doesn't answer the question then you need to clarify what you mean by it. -

PerceptionAre you saying that there are colorless rainbows? — creativesoul

It's not clear what you mean by the question, but I'll quote Newton's Opticks:

The homogeneal Light and Rays which appear red, or rather make Objects appear so, I call Rubrifick or Red-making; those which make Objects appear yellow, green, blue, and violet, I call Yellow-making, Green-making, Blue-making, Violet-making, and so of the rest. And if at any time I speak of Light and Rays as coloured or endued with Colours, I would be understood to speak not philosophically and properly, but grossly, and accordingly to such Conceptions as vulgar People in seeing all these Experiments would be apt to frame. For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour.

Rainbows look coloured because the various wavelengths of light cause various neurological activity in the visual cortex producing various colour percepts. This is the scientific fact. -

PerceptionColors are unlike chemicals. — creativesoul

Correct, they are like tastes. They are mental percepts caused by neurological activity, often in response to sensory stimulation. -

PerceptionThe light without color?

Earlier you forwarded the claim "there is no color in light". The visible spectrum is light. If there is no color in light, and the visible spectrum is light, then it only follows that there is no color in the visible spectrum.

Yet you offer a rainbow called the visible spectrum.

Colorless rainbows. — creativesoul

Light is just electromagnetic radiation, which is the synchronized oscillations of electric and magnetic fields. Colour is not a property of these fields. When it stimulates the eyes this causes neurological activity in the visual cortex, producing colour percepts. Just like chemicals stimulating the tongue cause neurological activity in the gustatory cortex, producing taste percepts. Colours are no more "in" light than tastes are "in" sugar.

Your naive projection has long since been refuted by physics and neuroscience. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?

There is no problem. The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains five words" is both meaningful and true. The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is both meaningful and false. It's that simple. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?

What are you talking about?

It’s really simple; the self-referential sentence “this sentence contains five words” is meaningful. I understand what it means, you understand what it means, and everyone else understands what it means. It’s not some foreign language or random combination of words. And we can count the words in the sentence to determine that it’s true.

You’re trying to create a problem where there is none. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?I totally agree that there is nothing problematic with the sentence "this sentence contains five words", and can indeed be a meaningful sentence.

As long as "this sentence contains five words" is not referring to itself. — RussellA

It’s meaningful even when it’s referring to itself. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?

The redundancy theory of truth usually applies to all sentences, whether it be "this sentence contains five words" or "it is raining". Seems strange to only apply it to self-referential sentences.

But even then, there's still nothing problematic with the sentence "this sentence contains five words". It is meaningful, despite your protestations to the contrary. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?Therefore, how can any one say that "this sentence contains five words" is true if no one knows which sentence is being referred to? — RussellA

In context we do know.

If I hold out an apple and say "this apple is red" then it's obvious that I'm referring to the apple in my hand and not the apple on the table behind me, and so what I say is true iff the apple in my hand is red.

If you want to be explicit, then:

The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains five words" is true.

The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is false. -

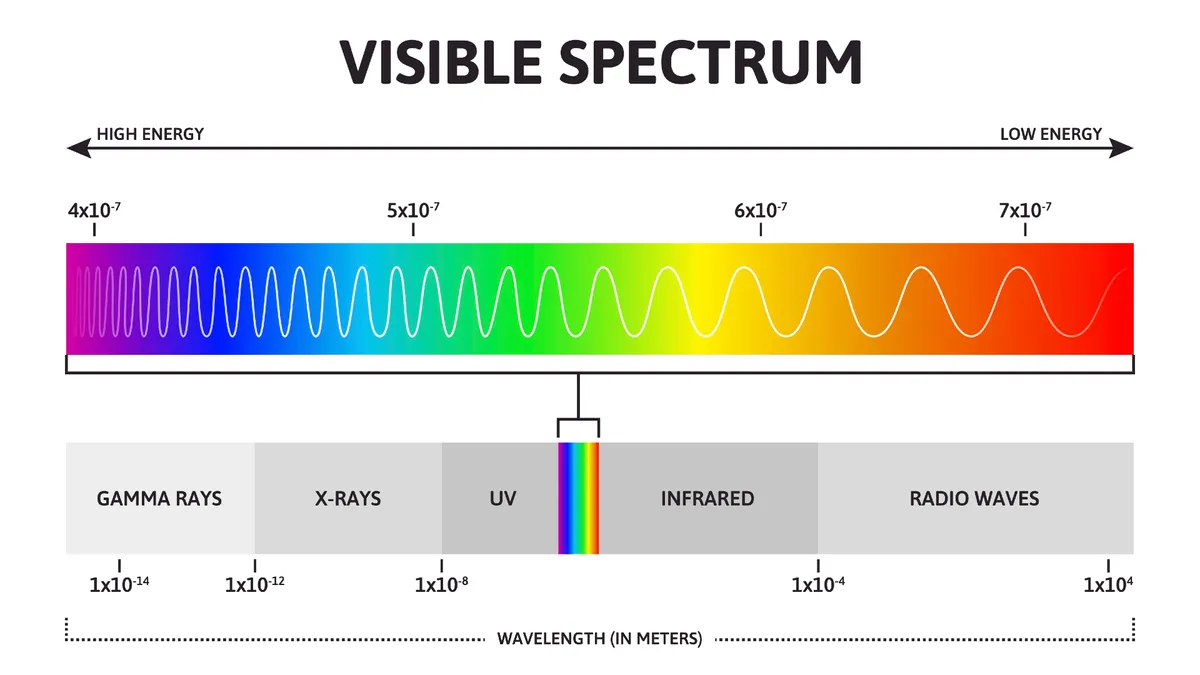

PerceptionHere's the visible spectrum.

There is a clear distinction between wavelengths of light and the corresponding colour. We can certainly conceive of a variation of this image with the colour red on the left, the colour violet on the right, but the wavelength staying as it is, with the shorter wavelength on the left and the longer wavelength on the right. Such could even be the case for organisms with a different biology, and so a different neurological response to the same stimulation. We even see examples of that with the dress, where different colours are seen by different people despite looking at the same screen emitting the same light.

And the fact that we use the adjective "red" to describe tomatoes because they look to have the colour on the right is completely irrelevant. They look that way because they reflect that wavelength of light, and our biology just happens to be such that objects which reflect that wavelength of light look to have that colour. That's all there is to it.

But the colour just is that mental percept, falsely believed by the naive realist to be a mind-independent property of the tomato. Physics and neuroscience has taught us better. -

PerceptionThere is no red pen while dreaming and hallucinating red pens. — creativesoul

So? I'm talking about colours, not pens. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?Similarly, it is not correct to say that the sentence "this sentence contains five words" is true because it contains five words. — RussellA

Yes it is. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?All I'm trying to say is that an expression that self-refers cannot be grounded in the world — RussellA

Yes it can.

The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains five words" is true because it contains five words.

The self-referential sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is false because it doesn't contain fifty words.

This is incredibly straightforward. -

PerceptionYour equivocating "red". — creativesoul

I am being very explicit with what I mean by the word "red", which is the opposite of equivocation. I'm saying that the colour red, as ordinarily understood, is the mental percept that 620-750 light ordinarily causes to occur, and that this mental percept exists when we dream, when we hallucinate, and when 620-750 light stimulates our eyes.

Any other use of the word "red", e.g. to describe 620-750 light, or an object that reflects 620-750 light, is irrelevant, because the relevant philosophical question is "do objects like tomatoes, strawberries and radishes really have the distinctive [colour] property that they do appear to have?", and this question is not answered by noting that we use the word "red" in these other ways. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?My question is, if the expression "this sentence" within "this sentence contains fifty words" is referring to itself, ie referring to "this sentence contains fifty words", then how can there be any grounding in the world? — RussellA

It's grounded in that we can count how many words are in the sentence "this sentence contains fifty words". There are five words, not fifty, and so the sentence is false. -

PerceptionI also asked what the difference was between the mental percept that 620-750 light ordinarily causes to occur and seeing red, and dreaming red.

You claimed "nothing" as an answer to all three questions. If there is no difference between four things, then they are the same.

They're all experiences. — creativesoul

The red part of hallucinating red, dreaming red, and seeing red are all the same thing; the occurrence of that mental percept, either reducible to or supervenient on neural activity in the visual cortex, that is ordinarily caused by 620-750 light stimulating the eyes.

The when and how it is caused to occur is then what distinguishes dreams, hallucinations, and non-hallucinatory waking experiences. It's a dream when it occurs when we're asleep, it's an hallucination when it occurs when we're awake and in response to something like drugs, and it's a non-hallucinatory waking experience when it occurs when we're awake and in response to light stimulating the eyes. -

Zero division revisitedIn the hyperreal number line, it's wrong. In this line, 0 is one of the possible values of h, which is defined as a number which, for all values of n, is greater than -n and less than n. From this it follows that any number divided by 0 equals infinity, because 0 is a non-finite value equal to every other value within h. And thereby the calculus is made respectable. — alan1000

No.

See division by zero:

In the hyperreal numbers, division by zero is still impossible. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?

"this sentence contains five words" is grounded and is true.

"this sentence contains fifty words" is grounded and is false.

"this sentence is false" is ungrounded and is neither true nor false. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?You say that the sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is false.

But you don't know that. — RussellA

I do know that. It refers to itself, it contains five words, and so it doesn’t contain fifty words.

If "this sentence" is referring to itself, ie, "this sentence contains fifty words", then both the SEP and IEP discuss the problems of self-referential expressions.

The SEP article on the Liar Paradox starts with the sentence "The first sentence in this essay is a lie"

The IEP article Liar Paradox talks about "this sentence is a lie" — RussellA

They are discussing the liar paradox. We are not discussing the liar paradox. We are discussing the sentences "this sentence contains five words" and "this sentence contains fifty words".

From the SEP article on self-reference:

... self-reference is not a sufficient condition for paradoxicality. The truth-teller sentence “This sentence is true” is not paradoxical, and neither is the sentence “This sentence contains four words” (it is false, though). -

PerceptionMaybe replace "of" with "about"? In the sense in which intentionality emerges from our brains with 'mental objects' being about distal objects? — wonderer1

What does it mean to say that brain activity is about distal objects?

Regardless, our primary concern isn't with intentionality but with appearances. As asked by Byrne & Hilbert (2003), "do objects like tomatoes, strawberries and radishes really have the distinctive [colour] property that they do appear to have?".

Prima facie one can claim that distal objects are the intentional object of perception but also that the visual imagery (e.g. the shape and colour) they cause us to experience does not resemble their mind-independent nature (much like we'd say the same about their smell and taste), i.e. maintaining the Kantian distinction between noumena and phenomena. That strikes me as being indirect realism rather than direct realism, not that the label really matters. -

Perception

Phenomenal consciousness is either reducible to or supervenient on brain activity. The only connection between distal objects and brain activity is that distal objects often play a causal role in determining brain activity. This is what the science shows.

Given this, it's not at all clear what 'direct perception' is. That phenomenal consciousness is 'of' distal objects? What is the word 'of' doing here? If, for the sake of argument, phenomenal consciousness is reducible to brain activity then this amounts to the claim that brain activity is 'of' distal objects. What does that even mean?

It strikes me that 'direct perception' requires a very different (unscientific) interpretation of phenomenal consciousness, e.g. some kind of extended immaterial mind that reaches out beyond the body.

Regardless, it is a fact that colours are constituents of phenomenal consciousness, and so an explanation of colours requires an explanation of phenomenal consciousness. The hard problem is still unsolved, and so the best we can do is recognize the neural correlates of colour percepts. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?That's why there is a SEP article on the Liar Paradox. — RussellA

But you weren't talking about the liar paradox. You were talking about the sentences "this sentence contains five words" and "this sentence contains fifty words". These two sentences are meaningful, with the first being true and the second being false.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum