Comments

-

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

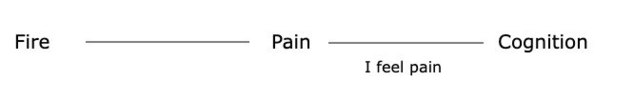

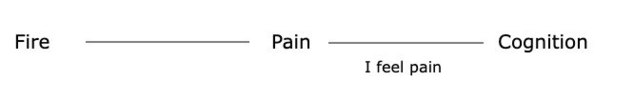

I may have been overly simplistic in my account but the point stands: I feel pain, pain is not a distal object/property but a mental/neurological phenomena, and so the thing that I feel is not a distal object/property but a mental/neurological phenomena. The same for smells and tastes and colours.

You can argue that this mental/neurological phenomena involves a variety of different mental/neurological processes rather than just some simple sui generis qualia, but it still admits that it is some mental/neurological phenomena that is experienced rather than some distal object/property. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI don’t doubt the brain is involved, but clearly the toe is as well. I’m just wondering the biology of “experience”, for instance how far from the brain it extends. — NOS4A2

The toe is the trigger. It's where the sense receptors are. But the sense receptors are not the pain. Pain occurs when the appropriate areas of the brain are active. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe heater grate to my right is not a mental representation. It is a distal object. It's made of metal. It has a certain shape. It consists of approximately 360 rectangle shaped spaces between 48 structural members. The spacing is equally distributed left to right as well as top to bottom. However, the left to right spacing is not the same as the top to bottom.

The 'mental representation', whatever that may refer to, cannot be anywhere beyond the body.

According to you, all we have direct access to and thus direct knowledge about is mental representations.

Where is the heater grate? — creativesoul

We have direct perceptual knowledge of our body's response to stimulation. We have indirect perceptual knowledge of the distal objects that play a causal role in that stimulation.

The grammar of "I experience X" is appropriate for both direct (I feel pain) and indirect (I feel the fire) perception. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe idea that we have scientific knowledge relies on the assumption that we have reliable knowledge of distal onjects. Attempting to use purportedly reliable scientific knowledge to support a claim that we have no reliable knowledge of distal objects is a performative contradiction. — Janus

I didn't say that we don't have reliable knowledge, only that we don't have direct perceptual knowledge. Even the direct realist must admit that many of the things we know about in science, e.g. electrons and the Big Bang, are not things that we have direct perceptual knowledge of. Is it a performative contradiction for a direct realist to use a Geiger counter?

Alternatively, we can argue like this:

If direct realism is true then scientific realism is true, and if scientific realism is true then direct realism is false. Therefore, direct realism is false.

The direct realist would have to argue that direct realism does not entail scientific realism (and reject scientific realism) or that scientific realism does not entail indirect realism. -

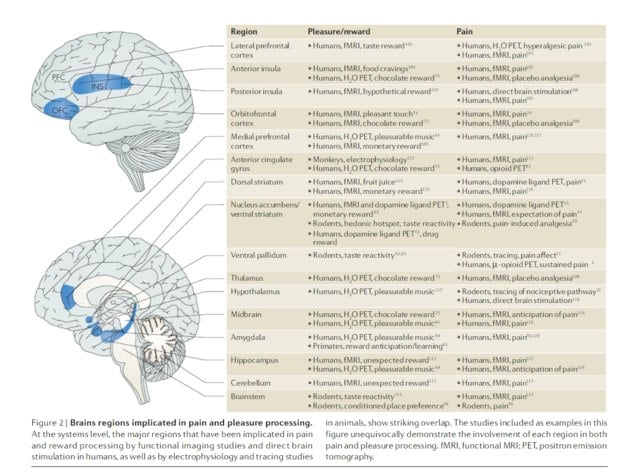

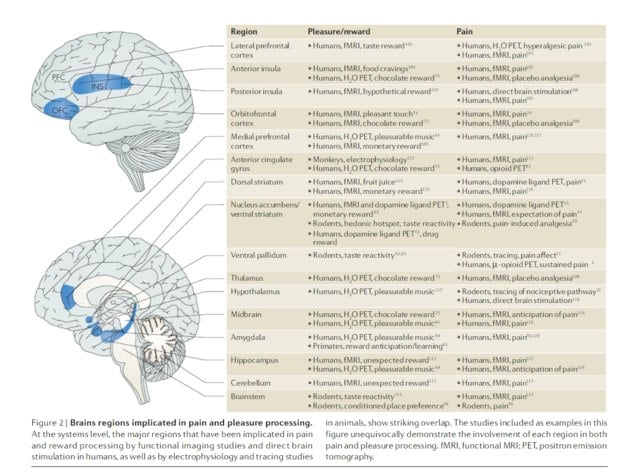

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThen wouldn't experience be limited to the prefrontal cortex — NOS4A2

From a common neurobiology for pain and pleasure:

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIf I stub my toe, injure my toe, and feel the pain in my toe, is it your position that I am feeling it in my prefrontal cortex? — NOS4A2

I think that there are pain receptors in the toe, that these send signals to the brain, and then there is pain when the relevant areas in the brain are active. The brain is clever and able to make it seem as if the pain is literally in the foot, but that cleverness also leaves us susceptible to phantom limb syndrome. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIs the "I" that feels pain the organism or the organism's cognition? — NOS4A2

The cognition. I believe it’s to be found in the prefrontal cortex, whereas pain is in the somatosensory cortex. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismDreams are not perceptions, and "hearing voices" is an abnormal case of perception. — Luke

It is nonetheless the case that I see and hear things when I dream and hallucinate and that the things I see and hear when I dream and hallucinate are mental phenomena. The Common Kind Claim says that waking veridical experiences are of the same kind as dreams and hallucinations (e.g. the activity of the sensory cortexes) – differing only in their cause – and so that the things I see (e.g. colours) and hear when having a waking veridical experience are also mental phenomena.

Your picture suggests otherwise. — Luke

Perhaps this will make it clearer:

The same principle holds for smelling and tasting and hearing and seeing. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe picture maintains what I consider to be the false assumption of indirect realism: that we require a second-order cognition/awareness/perception in order to perceive the first-order perceptions. In other words, cognition/awareness/perception of perceptions, which seems to imply an infinite regress. Perceptions (i.e. first-order perceptions) are here treated as not something already present to consciousness, or as if they were themselves external objects. — Luke

Do I see colours when I dream? Does the schizophrenic hear voices when hallucinating? I say "yes" to both.

This is where you're getting confused by grammar into thinking that indirect realists are saying something they're not. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhat is useful is knowing that the apple is either ripe or rotten and the color of the apple informs us which is the case. — Harry Hindu

Okay. We have direct knowledge of colours, which are a mental phenomenon. Given that we have inferential – i.e. indirect – knowledge of the apple's ripeness, which is a mind-independent property.

Our perception of the apple's mind-independent property is indirect.

What is the "I" that is made indirectly aware via mental phenomenon? How is it separate from the colours, mental phenomenon and other objects to say that the mental phenomenon is an "intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware..." — Harry Hindu

They're different aspects of consciousness, resulting from different areas of brain activity. The blind man has a self but doesn't experience visual phenomena because his visual cortex doesn't function. -

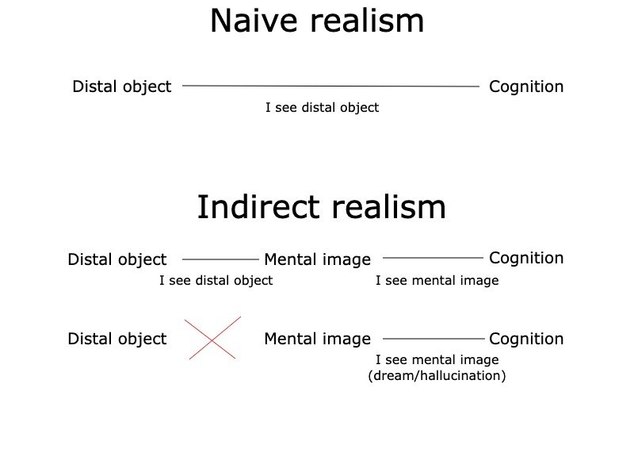

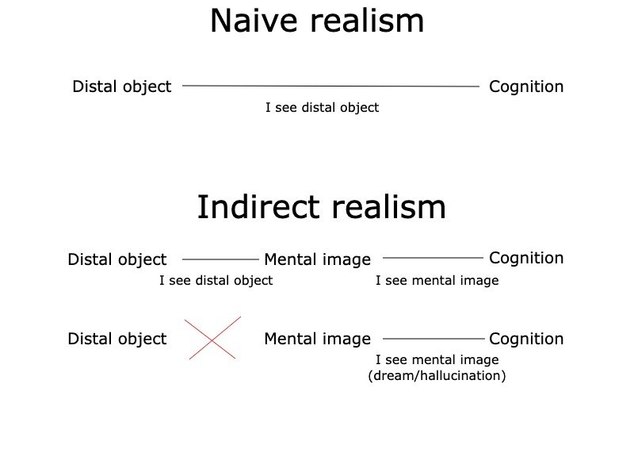

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI take it that the position of indirect realism is that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. And the position of naive realism is that perception always provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects? — Luke

Take the picture here. If indirect realism is true then if we remove the mental image then we have no knowledge of the distal object (or, to be more precise, any knowledge of the distal object has been gained by some means other than perception). And I believe that's correct. The mental image is the necessary intermediary. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismAnother picture that may prove helpful, with the lines representing some relevant causal connection.

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI don't follow. In what sense is your knowledge indirect here? Is the wavelength of the light a property of the distal object? — Luke

I know that I see the colour red.

I know that in most humans seeing the colour red usually occurs when the eyes react to light with a wavelength of 700nm.

I infer from this that I am looking at an object that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm.

Of course this is only true because I am somewhat educated in science. For many, e.g. young children, all they know is that they see the colour red. They don't know anything about electromagnetism and so don't know anything about the distal object's mind-independent properties. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

For example, we see colours. As per the Standard Model, colours are not a property of distal objects. Distal objects are just a collection of wave-particles. Colours are a mental phenomenon often caused by the body responding to particular wavelengths of light. I have direct knowledge of the colour red and indirect knowledge of a distal object reflecting light with a wavelength of 700nm. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI don't particularly like my own formulation of (Shrimp) btw, as it bifurcates seeing as a perceptual act and classification as a linguistic one, whereas there's evidence that the two are reciprocally related - both predictively/inferentially/causally and phenomenologically (citation needed). — fdrake

Are you suggesting that deaf and illiterate mutes don't see colours (or see everything to be the same colour)?

You could end up with a statement like:

(Shrimp) Mantis Shrimp Human sees X as P(X) and calls it "P(X)" if and only if human sees X as Q(X) and calls it "Q(X)".

Predicating of the distal object X now makes sense because we've reintroduced the idea that properties of distal objects influence the kinds they are seen and labelled as.

Do you think you need a numerical identity between the state of being that Mantis Shrimp Human has when they count X as P(X) and the human's that counts X as Q(X) even when P and Q have the same extension? — fdrake

I'm not entirely sure what you're trying to ask here.

My argument is that:

1. There is some stimulus X

2. There is some organism A and some different organism B

3. Given their different physiologies, organisms A and B have different experiences when stimulated by stimulus X

4. Some of the words that organisms A and B use to presumptively describe X in fact describe some aspect of their individual experience (and that is not an aspect of the other organism's experience).

5. Colour words are one such example. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe mantis shrimp example is a nice way of illustrating the flexibility and potential for expansion in our color concepts, while still maintaining a realist commitment to colors as objective properties of objects. — Pierre-Normand

This is equivocation. There is "colour" as an object's surface disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and there is "colour" as the mental phenomenon that differs between those with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision (and that occurs when we dream and hallucinate).

Despite sharing the same label these are distinct things – albeit causally covariant given causal determinism.

Those with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision will agree that some object reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, but they will see it to have a different colour appearance.

They'd still ascribe the colors within this richer color space to the external objects that they see. — Pierre-Normand

If they're direct realists, and they'd be mistaken. Naive colour realism is disproven by our scientific understanding of perception and the world. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIt would be interesting to hear what a human with his eyes replaced with those of a mantis shrimp (with their 12 channel colour vision compared to our 3) would say.

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismFurthermore, people who disagree about the interpretations of the picture can communicate their disagreement by pointing at external paint color samples that are unambiguously blue, black, gold and white to communicate how it is that the pictured dress appears to be colored to them. Here again, their agreement on the color of the samples ought to give you pause. — Pierre-Normand

It doesn't give me pause. Given that our eyes and brains are mostly similar, and given causal determinism, it stands to reason that the same kind of stimulus will mostly cause the same kind of effect.

But it is still the case that the cause is not the effect and that colour terms like "red" and "blue" can be used to refer to both the cause and the effect, and so you need to take care not to conflate the two, but it seems that direct realists do conflate. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI'd now like to discuss an issue with you. Consider the definition expressed in the sentence: "For an apple to be red means that it has the dispositional property to visually appear red under normal lighting conditions to a standard perceiver." Might not a subjectivist like Michael complain that this is consistent with an indirect realist account that views redness as the (internal) subjective states that "red" apples are indirectly or inferentially believed to cause (but not seen to have)? Or else, Michael might also complain that the proposed definition/analysis is circular and amounts to saying that what makes red apples red is that they look red. Although, to be sure, our "in normal conditions" clause does some important work. I did borrow some ideas from Gareth Evans and David Wiggins to deal with this issue but I'd like to hear your thoughts first. — Pierre-Normand

I think you're overcomplicating it, being "bewitched by language" as Wittgenstein would put it.

An apple reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm. When our eyes respond to light with a wavelength of 700nm we see a particular colour. We name this colour "red". We then describe an object that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm as "being red".

The indirect realist recognises that the colour I see in response to my eyes responding to a particular wavelength of light (and the colour I see when I dream and hallucinate) is distinct from an object's surface layer of atoms and its disposition to reflect a particular wavelength of light. The indirect realist recognises that this colour I see is a mental phenomenon and that this colour is the intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware of an object with a surface layer of atoms with a disposition to reflect light with a wavelength of 700nm (assuming that this is a "veridical" experience and not a dream or hallucination).

Perhaps this is clearer if we consider something like "the fire is painful" rather than "the apple is red". -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

This appears to be equivocation. We use the term "colour" to refer to both the disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and to the mental phenomenon that is caused by our eyes reacting to a particular wavelength of light, but these are two different things.

This is evidenced by the fact that we can make sense of different people seeing a different coloured dress when looking at this photo:

When I say that I see a white and gold dress and you say that you see a black and blue dress, the words "white", "gold", "black", and "blue" are not referring to some spectral reflectance property (which is the same for the both of us) but to some property of our mental phenomena (which is different for the both of us). The same principle holds for the colours we see when we dream and hallucinate.

Indirect realism accepts the existence of these mental colours and claims that they are the "intermediary" or "representation" of which we have direct knowledge and through which we have indirect knowledge of a distal object's spectral reflectance properties.

Whereas direct realism would entail the naive realist theory of colour.

As I see it, your account simply redefines the meaning of "direct perception", which I think is best understood as explained here and here.

See also Semantic Direct Realism where Robinson explains that the same kind of redefinition occurs for other so-called "direct" realisms like intentionalism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThe relevant issue is whether we have direct perceptions of real objects, not direct knowledge of perceptions. — Luke

The epistemological problem of perception concerns whether or not perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects.

One group claimed that it does, because perception is "direct". These people were called direct realists.

One group claimed that it doesn't, because perception is "indirect". These people were called indirect realists.

Therefore the meaning of "direct perception" is such that if perception is direct then perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore if perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects then perception is not direct.

Given our scientific understanding of the world and perception it is clear that perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore perception is not direct. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismHe may have refined his position since we began this discussion but he had long taken the stance that what I was focussing on as the content of perceptual experience wasn't how things really look but rather was inferred from raw appearances that, according to him, corresponded more closely to the stimulation of the sense organs. — Pierre-Normand

I am saying that appearances are mental phenomena, often caused by the stimulation of some sense organ (dreams and hallucinations are the notable exceptions), and that given causal determinism, the stimulation of a different kind of sense organ will cause a different kind of mental phenomenon/appearance.

The naïve view that projects these appearances onto some distal object (e.g. the naïve realist theory of colour), such that they have a "real look" is a confusion, much like any claim that distal objects have a "real feel" would be a confusion. There just is how things look to me and how things feel to you given our individual physiology.

It seems that many accept this at least in the case of smell and taste but treat sight as special, perhaps because visual phenomena are more complex than other mental phenomena and because depth is a quality in visual phenomena, creating the illusion of conscious experience extending beyond the body. But there's no reason to believe that photoreception is special, hence why I question the distinction between so-called "primary" qualities like visual geometry and so-called "secondary" qualities like smells and tastes (and colours).

Although even if I were to grant that some aspect of mental phenomena resembles some aspect of distal objects, it is nonetheless the case that it is only mental phenomena of which we have direct knowledge in perception, with any knowledge of distal objects being inferential, i.e. indirect, entailing the epistemological problem of perception and the viability of scepticism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

I don’t see how his account differs from indirect realism. Indirect realists simply claim that the thing we have direct knowledge of in perception is some sort of mental phenomenon, not some distal object, and so our knowledge of distal objects is indirect, entailing the epistemological problem of perception.

We can argue over what sort of mental phenomenon is the direct source of knowledge - sense data or qualia or representation or appearance or processed phenomenological content or other - but it all amounts to indirect realism in the end. -

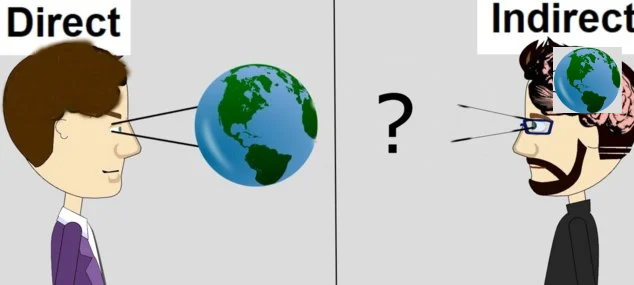

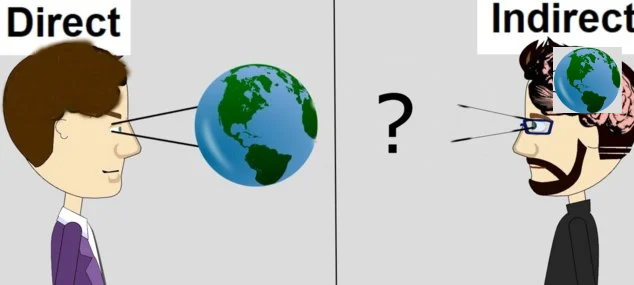

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismHow do you conceptualise a distal object in the second construal of indirect realism? — fdrake

Depends on the indirect realist.

Some may believe that distal objects resemble our mental image, and so would replace the question mark with the Earth as shown in the person’s head.

Some may believe that distal objects resemble our mental image only with respect to so-called "primary" qualities, and so would replace the question mark with an uncoloured version of the Earth as shown in the person’s head.

Some may believe that distal objects do not resemble our mental image at all. A scientific realist would replace the question mark with the wave-particles of the Standard Model. A Kantian wouldn’t replace the question mark at all, simply using it to signify unknowable noumena.

What defines them as being indirect realists is in believing that we have direct knowledge only of a mental image. Direct realists believe that we have direct knowledge of the distal object because nothing like a mental image exists (the bottom drawing of direct realism). -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI think the issue is that people misleadingly think of this as being the distinction between direct and indirect realism:

When in fact it is this:

-

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismOn this view, phenomenology is concerned with describing and analyzing the appearances of those objects themselves, not the appearances of some internal "representations" of them (which would make them, strangely enough, appearances of appearances). — Pierre-Normand

The indirect realist doesn’t claim that there are “appearances of appearances”.

The indirect realist claims that a distal object's appearance is the intermediate representation.

We have direct knowledge of a distal object's appearance and through that indirect knowledge of a distal object.

You're describing indirect realism but calling it direct realism for some reason.

The direct realist rejects any distinction between a distal object's appearance and the distal object itself, entailing such things as the naive realist theory of colour. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismRather, what we are immediately conscious of is the already "processed" phenomenological content. So an indirect realist account should identify this phenomenological content as the alleged "sense data" that mediates our access to the world, not the antecedent neural processing itself. — Pierre-Normand

If someone claims that the direct object of perceptual knowledge is the already-processed phenomenological content, and that through this we have indirect knowledge of the external stimulus or distal cause, would you call them a direct realist or an indirect realist?

I'd call them an indirect realist. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThese are the three positions:

1. Naive realism: a) naive realism is true and b) I experience distal objects

2. Indirect realism: a) naive realism is false and b) I experience mental phenomena

3. Non-naive direct realism: a) naive realism is false and b) I experience distal objects

Each a) is the relevant philosophical issue that concerns the epistemological problem of perception.

Each b) is an irrelevant semantic issue. They are not mutually exclusive given that "I experience X" doesn't just mean one thing.

Naive realism is false and I experience both distal objects (e.g. apples) and mental phenomena (e.g. colours and pain).

Therefore indirect realism and non-naive direct realism are both true and amount to the same philosophical position; the rejection of naive realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI also believe that distal objects are constituents of experience in the sense that you could not have an experience of a distal object without them. — Luke

That's not the sense that is meant by the naive realist and rejected by the indirect realist. The sense that is meant by the naive realist and rejected by the indirect realist is the sense that would entail naive realism.

Why wouldn't you use the same argument against naive realists? — Luke

Because this is what naive realism claims:

"Distal objects are constituents of experience such that experience provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects, and so there is no epistemological problem of perception."

This claim has nothing to do with the grammar of "I see X".

Your insistence of continually addressing the grammar of "I see X" is the very conceptual confusion that I am trying to avoid. It's a red herring. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIs the dispute between naive realists and indirect realists also "an irrelevant argument about grammar"? — Luke

No. Naive realists believe that distal objects are constituents of experience and so that experience provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. That's a substantive philosophical dispute.

I don't see how this example is related to distal objects. — Luke

In this case I'm being imprecise with the term "distal object" to mean anything outside the experience, and so including body parts, such that my skin is a distal object. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismNaive realists and non-naive realists both claim that we see distal objects. Indirect realists say instead that we see representations. — Luke

Which is an irrelevant argument about grammar. From my previous post:

Both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that colours are a mental representation of some distal object's surface properties. Both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that we see colours. Therefore, both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that we see mental representations.

Experiencing a mental representation and experiencing a distal object are not mutually exclusive. "I feel pain" and "I feel my skin burning" are both true. The grammar of "I experience X" is not restricted to a single meaning.

The relevant philosophical issue is that distal objects are not constituents of experience and so that our experience only provides us with indirect knowledge of distal objects. Everything else is a red herring. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismTherefore, Big Ben is not a constituent of a photograph of Big Ben? — Luke

Correct. The photograph is in my drawer. Big Ben is not in my drawer. The only things that constitute the photo are its physical materials.

Surely Big Ben is a component of the photograph. It's the subject of the photograph.

What does it mean for something to be the subject of the photograph? What does it mean for something to be the subject of a book? It's entirely conceptual. The conceptual connection between a photograph or book and their subject does not allow for direct knowledge of their subject. Photographs and books only provide us with indirect knowledge of their subject. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismThis is the distinction between non-naive realism and indirect realism. Indirect realists holds that we perceive perceptions or mental representations, whereas non-naive realists holds that perceptions are mental representations and that they represent external objects. — Luke

Both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that colours are a mental representation of some distal object's surface properties. Both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that we see colours. Therefore, both indirect and non-naive direct realists believe that we see mental representations.

Experiencing a mental representation and experiencing a distal object are not mutually exclusive. "I feel pain" and "I feel my skin burning" are both true. The grammar of "I experience X" is not restricted to a single meaning.

The relevant philosophical issue is that distal objects are not constituents of experience and so that our experience only provides us with indirect knowledge of distal objects. Everything else is a red herring. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismTo correct my earlier statement, what direct realists mean by "of" in "our perceptions are of distal objects" is the same as what we mean by "this photograph is of Big Ben" or "this painting is of Mr Smith". Just as photographs or paintings represent their subjects, perceptions represents distal objects. — Luke

Direct realists say that the perceptual content represents external objects. — Luke

The representational theory of perception that claims that perceptual content is some mental phenomenon (e.g. sense data or qualia) that represents the external world is indirect realism, not direct realism.

Direct realism, in being direct realism, rejects the claim that perception involves anything like mental representations (which would count as an intermediary).

If by "the experience is of distal objects" you only mean something like "the painting is of Big Ben" then indirect realists can agree. The relevant philosophical issue is that we only have direct knowledge of the experience/painting and only indirect knowledge of distal objects/Big Ben, hence the epistemological problem of perception. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismWhat do you mean by "our perceptions are of distal objects" when you say it is false? — Luke

I don't say that it's false. I have been at pains in this discussion (and others over the past few years) to explain that trying to address the epistemological problem of perception in these terms is a conceptual confusion. It's an irrelevant argument about grammar.

"I experience X" doesn't just mean one thing. I can say that I feel pain, I can say that I feel my hand burning, or I can say that I feel the fire. I can say that the schizophrenic hears voices. I can say that some people see a white and gold dress and others see a black and blue dress when looking at the same photo.

These are all perfectly appropriate phrases in the English language, none of which address the philosophical issue that gave rise to the dispute between direct and indirect realism (as explained here).

How does that follow? — Luke

If A is true and B is false then A and B do not mean the same thing.

If indirect realists believe that "our perceptions are of distal objects" is false but believe that "our perceptions are caused by distal objects" is true then when they say "our perceptions are not of distal objects" they are not saying "our perceptions are not caused by distal objects."

It is not a dispute over different meanings of the phrase "of distal objects", is it? — Luke

The dispute between naive realists and indirect realists is not a semantic dispute. Their dispute is a legitimate philosophical dispute over the epistemological problem of perception.

The dispute between non-naive direct realists and indirect realists is an irrelevant semantic dispute. They agree on the philosophical issue regarding the epistemological problem of perception.

Even if there were no substantive dispute over whether our perceptions are of distal objects, you have still not addressed the other difference that I noted between the two parties: their different beliefs regarding perceptual content. — Luke

What does it mean to say that something is the content of perception? Perhaps you'll find that what indirect realists mean by "X is the content of perception" isn't what non-naive direct realists mean by "X is the content of perception", and so once again it's an irrelevant dispute about language.

I'll refer you again to Howard Robinson's Semantic Direct Realism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismDo you deny that indirect realists believe that our perceptions are only of mental representations or sense data? Or do you refuse to accept that non-naive direct realists believe that our perceptions can be of distal objects? — Luke

What does "our perceptions are of distal objects" mean?

Given that indirect realists believe that "our perceptions are of distal objects" is false but believe that "our perceptions are caused by distal objects" is true, it must be that "our perceptions are of distal objects" doesn't mean "our perceptions are caused by distal objects".

If what indirect realists mean by "our perceptions are of distal objects" isn't what non-naive direct realists mean by "our perceptions are of distal objects" then you are equivocating.

Assume that by "our perceptions are of distal objects" non-naive direct realists mean "our perceptions are ABC".

Assume that by "our perceptions are of distal objects" indirect realists mean "our perceptions are XYZ".

Non-naive direct realists believe that "our perceptions are ABC" is true. Indirect realists believe that "our perceptions are XYZ" is false.

Where is the disagreement?

And if non-naive direct realists agree with indirect realists that "our perceptions are XYZ" is false and if indirect realists agree with non-naive direct realists that "our perceptions are ABC" is true, then non-naive direct realism and indirect realism are the same. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismIn any case, it’s unfalsifiable and cannot be proven — NOS4A2

I might agree; realism, idealism, atheism, pantheism, and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics are all unfalsifiable and cannot be proven.

except when it comes to the science of perception. — NOS4A2

We can look at what follows if we are scientific realists and accept the literal truth of something like the Standard Model and the science of perception. If true, indirect realism follows.

Of course, you can be a scientific instrumentalist and reject the literal truth of the Standard Model and the science of perception if you wish to maintain direct realism, although there may be some conflict in rejecting the literal truth of something that you claim to have direct knowledge of. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismI’m not sure there is any good reason for the indirect realist to believe in any of them, since any evidence regarding anything about the external world lies beyond his knowledge. He doesn’t know what he is experiencing indirectly. Hell, he can’t even know that his perception or knowledge is indirect. — NOS4A2

His experience is the evidence. He has direct knowledge of his experiences. What best explains the existence of such experiences and their regularity and predictability? Being embodied within a greater external world, with his experiences being a causal consequence of his interaction with that greater external world.

This is the reasoning that leads one to believe in realism (and so for some direct realism) over idealism. -

Indirect Realism and Direct RealismGiven that any evidence of the external world lies beyond the veil of perception, or experience, is the realism regarding the external world a leap of faith? — NOS4A2

In a sense, hence why indirect realists claim that there is an epistemological problem of perception, entailing the viability of scepticism.

But the term "faith" is a bit strong. It's no more "faith" than our belief in something like the Big Bang or the Higgs boson is "faith". We have good reasons to believe in them given that they seem to best explain the evidence available to us. The indirect realist claims that we have good reasons to believe in the existence of an external world as it seems to best explain the existence and regularity and predictability of experience. -

Indirect Realism and Direct Realism

It's considered the most parsimonious explanation for the existence and regularity and predictability of experience.

Although subjective idealists disagree.

But given that direct and indirect realists are both realists we can dispense with considering idealism in this discussion.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum