Comments

-

BanningsWhat proof do you have of any of this? — Outlander

Proof that he's an adult or proof that he told us that he wants to be banned?

This is the proof that he told us that he wants to be banned, from the discussion I linked to above:

I do think it's rude that I explicitly asked Jamal also to be banned more than once, and for whatever reason he kept questioning me about it, in which I felt compelled not to respond just because I already answered the question. I have recently realized how much irritates me when people keep asking me to repeat myself.

So there: i did what was asked of me, now I'm going to ask that I get banned from this message board so that it's no longer a source of confusion and anxiety. Thank you. — ProtagoranSocratist

And this is the proof that he's an adult:

It's usually inconsequential, but during one college course i had a long time ago... — ProtagoranSocratist

I don't understand what either you or javi2541997 are expecting of us. For us to refuse to ban someone who asks to be banned because we clearly know better than them what's best for them? That would be incredibly condescending. -

BanningsBanned @ProtagoranSocratist because he asked us to: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/16297/i-dont-think-the-site-overall-is-very-well-designed/p1

-

A new home for TPF6. AI Autofill / Autocomplete

Offers context-aware writing suggestions to help users complete sentences or refine ideas as they type. — Jamal

As a programmer this is the only feature of Cursor that I use. I've never once asked it to generate code for me. I'm stubbornly old-fashioned. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?Many, MANY people are assuming that 'men' in isolation is referring to sex. Calling them idiots is not an argument. — Philosophim

It's not idiotic to believe that the word "men" only means "biological men". But if a very large number of people say things like "trans men are men" then there are two possible responses:

1. People who say "trans men are men" are suffering from a psychosis and believe that biological women who identify as men are biological men.

2. People who say "trans men are men" mean something else by "are men".

It's idiotic to assert or believe (1). -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?

Yes, some people aren't fluent in English or might not understand the distinction between sex and gender, but Philosophim isn't one of those people. He is arguing that the sentence "trans men are men" is ambiguous, showing that he clearly understands that the word "men" is a homonym and yet seems incapable or unwilling to use the rest of the sentence to sensibly resolve the appropriate meaning of the word as he would do with the sentence "bats are flying mammals". -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?So on this, I'm not sure there is anything more to be said. However what did need to be said was the answer to my question. You don't even have to agree on the way most people will interpret the phrase, but it is clear there is more than one way to interpret the phrase, and as such it is ambiguous. One of the essential tenants in philosophy is a disambiguation of terminology to allow clear thinking and rational thought. Anyone who is against getting rid of ambiguity in phrasing is being dishonest and manipulative in a discussion if they are not ignorant or rationally deficient. — Philosophim

The sentence "trans men are men" isn't ambiguous, just as the sentences "bats are flying mammals" and "bats are used in baseball" are not ambiguous. Anyone who isn't being intentionally dense can figure out the most plausible meaning of a homonym by just considering the sentence as a whole.

It is a very obvious strawman to interpret "trans men are men" to mean "biological women who identify as men are biological men", just as it is a very obvious strawman to interpret "bats are flying mammals" to mean "metal clubs are flying mammals". -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?

It’s very simple. Nobody who says “trans men are men” believes that biological women who identify as men are biological men. It’s absurd that this needs to be explained to you.

The only coherent objection to the claim “trans men are men” is to argue that they are misunderstanding or misusing the word “men” — that it only means “biological men” — but this objection, although coherent, is demonstrably false.

The English language, like every other natural language, has its ambiguities and homonyms, and it’s incorrect to claim that it doesn’t and pointless to insist that it shouldn’t. If it concerns you that much then go learn Lojban. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?

It’s common sense that there is no widespread mass psychosis about the sex organs of transgender people. This is most obvious given that these people are referred to as “transgender” rather than as “cisgender”. The very words people use proves beyond all reasonable doubt that they are not hallucinating or delusional.

You’re just doubling down on a completely unreasonable accusation, and then shifting the burden of proof. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?There are delusional people who believe this. — Philosophim

That some people suffer from psychosis does not justify your position. Common sense is sufficient to understand that most people aren’t suffering from hallucinations or delusions, and so the only rational conclusion is either a) other people misunderstand the (singular) meaning of the word “man” or b) the word “man” doesn’t just mean the singular thing you believe it to mean. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?

Again, if you interpret the phrase “trans men are men” as “trans men are biologically male” then that’s on you.

Do you honestly believe that people who say this are delusional about someone’s sex organs? Do you honestly believe that trans men hallucinate themselves to have a penis? Common sense and even the smallest principle of charity should make it obvious that you’re addressing the most absurd strawman. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?

I think that if you interpret the phrase “trans men are men” as “trans men are biologically male” then that’s on you. Given that the sentence starts with “trans men” it is immediately obvious that they are referring to those who are biologically female, and so the context of the ending phrase “are men” should be self-evident. -

Transwomen are women. Transmen are men. True or false?Late to this debate, but I take it that despite all the heat of the public debate, this is just an issue in metaphysics. — Clarendon

I don’t think it’s anything so complicated. It’s just people thinking that words have some singular meaning.

The English words “man” and “woman” can refer to (usually) straightforward biological properties but they can also refer to something psychological or cultural or social that is less easy to pigeonhole.

Arguing that trans men aren’t men because they don’t have XY chromosomes is as confused as arguing that chiroptera aren’t bats because they’re not metal clubs. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemI'm not sure what you mean this scenario to be. It's possible you mistyped something. — Pierre-Normand

A 3-sided die is rolled.

If it rolls a 1 then she is woken once on Tuesday.

If it rolls a 2 then she is woken once on Monday.

If it rolls a 3 then she is woken once on Monday. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

These are clearly different experiments:

1. If a D3 rolls a 1 then she is woken once on Tuesday, else she is woken once on Monday.

2. If a D2100 rolls a 1 then she is woken 2101 times on Monday, else she is woken once on Tuesday.

And these are clearly different questions:

a. What fraction of interviews does she expect to be Monday interviews as the number of experiments approaches infinity?

b. How confident is she that her current interview is a Monday interview if she knows that the experiment is only performed once?

Everyone agrees that the answers to (1a) and (2a) are the same: .

The paradox concerns (1b) and (2b). Intuitively, she ought be more confident in (1) than in (2), but if Elga’s reasoning is sound then she ought be equally confident. This counter-intuitive conclusion can't be justified simply by reinterpreting the question in such a way that (b) means the same thing as (a). Although in many cases the answer to (a) determines the answer to (b) it is a mistake to conflate the two, and I believe the paradox is peculiar precisely because this usual determination does not hold.

Given the common-sense interpretation of (b) she ought be fairly confident that her current interview in (1) is a Monday interview and almost certain that her current interview in (2) is a Tuesday interview. Any other degrees of belief just aren’t warranted, and arguments to the contrary seem to misrepresent the paradox and equivocate. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemI don't know if it's quite comparable but it reminds me of the Boltzmann brain paradox. Although the probability of a Boltzmann brain forming is vanishingly small, given sufficient time they would dwarf the number of "real" brains.

Should I then believe that I am most likely a Boltzmann brain?

Although perhaps this is best comparable to the variation where both a) the experiment is repeated 2101 times and b) I am made to forget which experiment I'm on. I think only then could the long-term average ratio of awakenings factor into my credence. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem(1) I believe that awakening episodes such a the one I am currently experiencing turn out to be (i.e. are expected by me to be) 1-awakenings (i.e. awakening episodes that have been spawned by a die landing on "1") two thirds of the time on typical experimental runs. — Pierre-Normand

Which is true.

But I believe the step from this to "therefore, my credence that this is a 1-awakening is " is a non sequitur.

This extreme example is a reductio ad absurdum that shows that given the peculiarities of the Sleeping Beauty experiment it is irrational for one's credence to be determined by the long-term average ratio of awakenings.

So it doesn't matter that (1) is true. Any rational person being subject to this experiment should be almost certain that a) the die didn't roll a 1, and so that b) this is not a 1-awakening. -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemI take SB's expected value to be a function of both her credence and of the payout structure. — Pierre-Normand

So then what is this calculation using pounds and pence?

I, however, don't take her credence to be a well defined value in the original Sleeping Beauty problem due to an inherent ambiguity in resolving what kind of "event" is implicitly being made reference to in defining her "current epistemic situation" whenever she awakens. — Pierre-Normand

I disagree that there's any ambiguity.

This is an "-sided die rolled a 1" awakening if and only if this is an "-sided die rolled a 1" experiment.

Therefore, a rational person's credence that this is an "-sided die rolled a 1" awakening must equal their credence that this is an "-sided die rolled a 1" experiment, because anyone who claims both of these isn't rational:

1. I believe it most likely that I am in a "die rolled a 1" awakening

2. I believe it most likely that I am not in a "die rolled a 1" experiment

And anyone who claims both of these isn't rational:

1. If I get to place a new bet each time I wake up then I believe it most likely that the die rolled a 1

2. If I only get to change my original bet each time I wake up then I believe it most likely that the die did not roll a 1

(on this point: what is your credence if you don't know the payout structure or if you don't get to place a bet at all?)

I really just think that there's only one correct answer, regardless of "interpretation" or payout structure (whether or not there even is is one, and whether or not it is known), and that answer is most obvious when we consider the 2100-sided die; a rational person's credence is , never . -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemYes, it sure is close. But not exact. — JeffJo

So you're willing to commit to the conclusion that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the 2100-sided die rolled a 1 is , i.e. she should be fairly confident that the die rolled a 1?

Because I take that as a reductio ad absurdum. If Sleeping Beauty is rational then her credence should be , i.e. she should be almost certain that the die didn't roll a 1.

The waking-day ratio is a red herring. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

These are your exact words:

Her credence in "1" as the die-roll result is N/(N+M-1). — JeffJo

If this is our experiment:

1. We roll a 2100-sided die

2. Sleeping Beauty is woken up over 2101 days if it rolls a 1

3. Sleeping Beauty is woken up just once if it doesn't roll a 1

Then and .

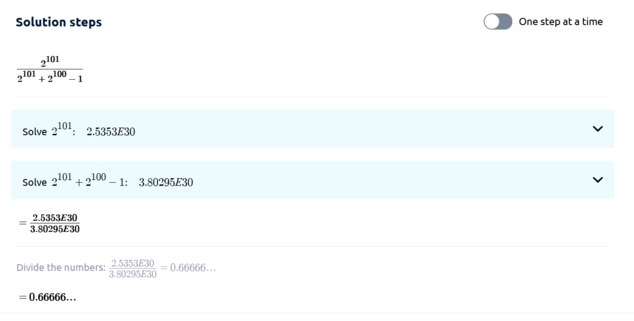

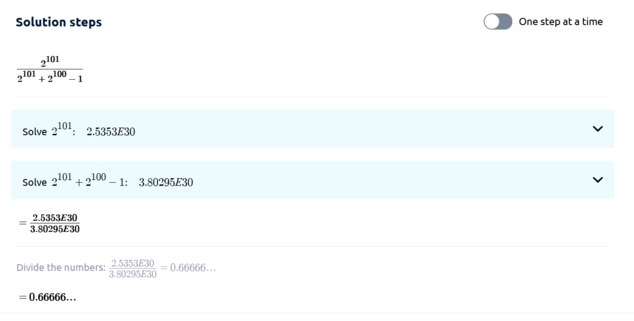

Therefore, according to your reasoning, her credence is which . You can see here if you don't believe me.

-

Sleeping Beauty Problem

It is a fact that if this is our experiment

1. We roll a 2100-sided die

2. Sleeping Beauty is woken up over 2101 days if it rolls a 1

3. Sleeping Beauty is woken up just once if it doesn't roll a 1

Then your reasoning entails that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the die rolled a 1 is .

Therefore, your options are:

1. Commit to the conclusion that her credence is

2. Accept that her credence isn't and so that your reasoning is fallacious

3. Arbitrarily decide that your reasoning only works for an grid of a sufficiently small size

So which is it?

I think that any rational person will go with (2). -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemAnd then presenting the 2/3 answer as a general case — JeffJo

I'm not.

I'm saying that if this is our experiment:

1. We roll a 2100-sided die

2. Sleeping Beauty is woken up over 2101 days if it rolls a 1

3. Sleeping Beauty is woken up just once if it doesn't roll a 1

Then your reasoning entails that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the die rolled a 1 is , because that's how the waking-day ratio works out.

And I think this is a reductio ad absurdum against your reasoning. A rational person's credence should just be . Therefore, it is wrong to consider the waking-day ratio. -

A new home for TPF

One of the things I really like about PlushForums is that when I click on a discussion it takes me to the last comment I viewed, and not just the first/last page.

Does Discourse do that? -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

These were your exact words:

Her credence when asked is 1/3, because of the four possible cells in the 2x2 array, one is eliminated and only one of the remaining three is Heads. — JeffJo

This can be generalised as:

Her credence when asked is , because of the possible cells in the array, are eliminated and only of the remaining has Outcome X.

In the traditional problem the rules are:

- A coin is tossed

- If the coin lands on tails then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1 and Day 2

- If the coin lands on heads then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

Given this, and where Outcome X is the coin landing on tails, the values are:

Your reasoning entails that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the coin landed on tails is .

In a slightly different version of the problem the rules are:

- A 6-sided die is rolled

- If the die rolls a 1 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1, Day 2, ... and Day 10

- If the die rolls a 2 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

- If the die rolls a 3 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

- If the die rolls a 4 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

- If the die rolls a 5 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

- If the die rolls a 6 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

Given this, and where Outcome X is the die rolling a 1, the values are:

Given that , your reasoning entails that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the die rolled a 1 is .

In my extreme version of the problem the rules are:

- A 2100-sided die is rolled

- If the die rolls a 1 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1, Day 2, ... and Day 2101

- If the die rolls a 2 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

- If the die rolls a 3 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

...

- If the die rolls a 2100 then Sleeping Beauty is woken on Day 1

Given this, and where Outcome X is the die rolling a 1, the values are:

Given that , your reasoning entails that Sleeping Beauty's credence that the die rolled a 1 is approximately .

Whereas Halfers will say the only thing that Sleeping Beauty needs to consider is the coin toss/die roll, and so her credence in each of these situations is:

- The coin landed on tails:

- The 6-sided die rolled a 1:

- The 2100-sided die rolled a 1: -

Sleeping Beauty ProblemWhy are you saying the values are wrong? Since there are one and a half awakenings on average per run, it's to be expected that the EV of a single bet placed on any given awakening be exactly two thirds of the EV of a bets placed on any given run. — Pierre-Normand

It's wrong because the expected returns aren't £33.333... if betting on heads or £66.666... if betting on tails.

I am not conflating the two. I am rather calculating the EV in the standard way by calculating the weighed sum of the payouts, where the payout of each potential occurrence is weighted by its respective probability (i.e. my credence in that occurrence being actual). I am pointing out that both the Halfer interpretation of SB's credence (that tracks payouts/awakenings) and the Thirder interpretation (that tracks payouts/runs) of SB's credence yield the exact same EV/run (and they also yield the same EV/awakening) and hence Halfer and Thirders must agree on rational betting strategies despite favoring different definitions of what constitutes SB's "credence". — Pierre-Normand

So then can you set out your calculations? These are mine:

I assume yours will take this form?

It just seems to me that you're putting the cart before the horse and arguing that because E(T) = 2 × E(H) then C(T) = which is a nonsensical inference.

And, once again, I think that this inference is shown most evidently to be nonsensical when we consider the case with the 2100-sided die. It just doesn't matter what the payout structure is or whether I'm asked my credence that the die rolled a 1, my credence that this is a die-rolled-a-1 run, or my credence that this is a die-rolled-a-1 awakening: my answer is always going to be , and I think any rational person would answer the same. -

A new home for TPF

The Online Safety Act applies to all websites that are accessible in the UK, regardless of where the owners live/are incorporated or where the website is hosted. -

A new home for TPF

I really don't understand what point you're trying to argue. The facts are that (a) if we are to continue to provide access to UK residents then we must comply with the Online Safety Act and that (b) it is better for a private limited company to risk being fined £18 million than for Jamal to risk personally being fined £18 million. -

A new home for TPF

I think you have a misunderstanding of the Online Safety Act. If we don't comply then the Office of Communications (Ofcom) can fine us (up to £18 million or 10% of revenue, whichever is higher) or take us down.

It has nothing to do with private individuals suing us because they believe they've been harmed. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

It wasn't a typo.

Given a 2100-sided die there are 2100 rows, and given that there are 2101 days there are 2101 columns. That gives us a 2100 × 2101 matrix, i.e. 2201 cells.

The "die rolled a 1" row has 2101 cells where I'm awake. Each other row has 1 cell where I'm awake.

So in total there are 2101 + 2100 - 1 cells where I'm awake. of these cells appear on the "die rolled a 1" row. Therefore, according to your reasoning, after waking up your credence that the die rolled a 1 is . -

A new home for TPF

He was banned — probably for low post quality — but then he created a new account, so we banned him again, but then he created a new account, so we banned him again, ...

This repeated literally hundreds of times. He just would not stop. Every day for months we were banning his new accounts and it was driving us crazy so we just gave up and turned off direct registration. -

A new home for TPFI don't see how the memory of this man is not all but water under the proverbial bridge. What have you to fear in the present day and age as far as this person is concerned? — Outlander

Are you asking about Marco?

He's an annoying fucking twat, as elucidated with exceptional eloquence here.

Suffice it to say he's the reason this forum became invitation-only. -

A new home for TPFI've been here for 5 years. I've seen the name "Porat" come up a few times, but with such intensity and quiet understanding between those who seem to know, it's... curious. — Outlander

Before https://thephilosophyforum.com there was another forum. The owner of the old forum sold it to a man named Eric Porat. Some of us had concerns about him, and the future of the forum, so Jamal made this place and we moved over. -

A new home for TPF

-

Sleeping Beauty Problem

As above, replace the coin with a 2100-sided die. If it lands on a 1 then you are woken up on 2101 days otherwise you are only woken up on one day. After being woken up you are asked your credence that the die landed on a 1. The experiment is not repeated.

If you follow your reasoning then you have to claim that your credence is . You believe that the die most likely landed on a 1. I take this as a reductio ad absurdum against your reasoning. It's a fallacy to think of the problem as being represented by a matrix. Not being woken up isn't an "activity" comparable to playing football, hence why it's a false analogy.

If this were to happen to me my credence would be . The die almost certainly didn't land on a 1. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

It's a false analogy because "not being woken up" is nothing like "playing football". It's a mistake to consider "Heads + Tuesday" at all. We can simplify the experiment as such:

1. On Sunday, Sleeping Beauty is put to sleep

2. A coin is flipped

3. On Monday, Sleeping Beauty is woken up and asked her credence that the coin landed on heads

4. If the coin landed on heads then Sleeping Beauty is told the outcome and the experiment ends

5. If the coin landed on tails then Sleeping Beauty is put back to sleep

6. On Tuesday, Sleeping Beauty is woken up and asked her credence that the coin landed on heads

7. Sleeping Beauty is told the outcome and the experiment ends

Her credence when asked is .

This is even more obvious when we replace the coin with a 2100-sided die. If it lands on a 1 then she is woken 2101 times, otherwise she is woken once. After being woken up she is asked her credence that the die landed on a 1. The experiment is not repeated.

Halfers say that her credence is and Thirders say that her credence is . I think any reasonable person would agree with the Halfer. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

If she is interviewed before playing football her credence that the coin landed on tails is not 1, but if she is interviewed after playing football her credence that the coin landed on tails is 1.

Playing football is additional information, but nothing like that is available in the traditional problem, and so your example is a false analogy. -

Sleeping Beauty Problem

If Monday is tennis and Tuesday is football then waking up and playing either tennis or football is new information that allows you to rule out one possibility: if you play tennis then you can rule out that today is Tuesday and if you play football then you can rule out that today is Monday.

You can't rule out that today is Monday or that today is Tuesday before playing either tennis or football, which is why your example is a false analogy. -

Can the existence of God be proved?If God does exist, then that is not God. — Bishop Whalon

This is such a nonsense claim. -

A new home for TPFI'll be making an announcement when it's open for new sign-ups. As I say, around March. — Jamal

I assume this means that the new site will use a new URL for a time? Because if the new site immediately uses https://thephilosophyforum.com then nobody will ever see the announcement on this site because this site will be using a different URL that nobody will know.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum