Comments

-

Death Positivity, the Anxiety of Death, and Flight from ItPerhaps angst isn't somehow intrinsic to human nature? It'd be difficult to assess as to what role death played within hunter-gatherer societies. — thewonder

There is cross cultural research on such things. And it shows that angst is fairly specific to modern society. You could start with the Catholic Church developing a whole guilt-based economy of social control.

Most cultures have some sort of ritual for the disposing of the bodies of the dead, and, so, I would be willing to posit that death is something that people feel a need to somehow come to terms with is somewhat universal. — thewonder

Yes it is also true that everything must be ritualised to give it social meaning. And death within a group is a major event, along with birth, entry into adulthood, getting ready to go hunting, and anything else.

So society just is a network of rituals designed to socialise it’s individuals. And the way of life that results is one that makes the best use of the available circumstances. I would agree death has to be a more significant event than most - especially when your total world is limited to a few hundred others at most. But being ritualised only means that it is part of the general need to socially construct a collective meaning.

These myths of eternal prosperity, I think, are born out of an incapacity to cope with the reality of death and are much older than any recent Postmodern phenomena. — thewonder

When you move from hunter gatherers to agrarian and hierarchical societies, death may indeed become far more ritualised - along with the whole of social life in general. Think of Victorian funerals and widows in black or embalmed bodies.

And then the 20th century with its atheism and rationality may have gone the other way. Both my parents wanted no funeral, no grave, no fuss at all. Just quick cremation in a cardboard box. That in itself is a somewhat ostentatious demonstration of some specific cultural values one could argue.

We can learn to think about the same material fact - an end to life - in entirely different ways. And what can make all of them right is their appropriateness within a functional social context. I stress functional. -

Death Positivity, the Anxiety of Death, and Flight from ItI thank you for such a lengthy and erudite post, which I have no real idea as to how to respond to other than to beg a question by asking you if you can, in good faith, claim that you really perceive the fate of our environment as being more important to you than your bucketlist of life experiences. — thewonder

Well I could see in the 1990s that 2050 was the bottleneck decade for humanity. So I've had plenty of time to adjust the two sides to my reaction. Personally, I feel I have things lined up as well they could be.

I can't really say that I would trade the life of an effective environmental activist for something like genuine love or a life of whirlwind adventure. — thewonder

Again, try Rupert Read for practical advice ...

Realistically, if you are still young, it is likely too late to change society and its collapse is going to deliver all the "whirlwind adventure" you could wish for.

You are speaking about death as a problem in a context that, with high probability, has only a couple of decades to run. So start making deep philosophical sense of that. :lol:

Perhaps that's selfish of me, but, I don't know that I believe that there are too many ascetic self-sacrificing types really out there or that such martyrdom isn't somehow instilled out of a kind of communal desperation. — thewonder

That was the problem with greenies. Too self-sacrificing. Very unappealing.

But then you get the preppers as another response to self-inflicted climate disaster. Buy guns, bunker down and look forward to the Mad Max show.

There are many reactions, and some are more thoughtful and useful in the actual situation we are in currently.

I don't know. My reaction to your post was one of nostalgia. And then chatteringmonkey said something interesting about decay positivity. My essential point is that the good old existential issue now has both its individual and collective dimensions being sharply felt. And that is an active area for a newly emerging philosophy of generalised societal collapse. It just feels more relevant. -

What is Information?I'm surprised how poorly understood the concept of integrated information is, given some of the queries, perhaps this needs a thread on it's own? — Pop

At a certain level, integrated information is just a truism. It is obvious - once you accept the brain employs some kind of neural code to construct "consciousness" - that a big problem is how all this local information, this individually triggered firing, then gets integrated into a large structured state of meaningful experiencing.

So that sets folk off down a path towards an emphasis on information processing and global self-organisation - a path which leads them towards the age-old habits of Cartesian representationalism and even the faux-monism of panpsychism.

The easy case against ITT is that if people like Tononi and Koch are happy to arrive at a destination like panpsychism, you know that you don't even want to waste time starting going down that particular road.

One can make a more technical case. But like quantum consciousness theories, why even waste your day?

I contrast this with Friston's Bayesian Brain model. Friston worked with Tononi in Edelman's lab as it happens. But Friston's approach struck me as immediately right even before he really got going.

Like most neuroscientists who are serious, he wouldn't even use a dualist and representational term like "consciousness" - except with those scare quotes around them. He understood that we are talking about the brain's embodied and functional modelling of reality - or rather its model of it being a self in a world. So that takes us into a different intellectual space - one where cognition is enactive and semiotic. It is just a fundamentally different orientation that leads to a very different understanding of nature.

Information is excellent for this, but I don't yet fully understand it. There is a lot to understand. I feel there is quite a lot of "new" philosophical meat on offer, but perhaps this is just new to me. — Pop

It is good you say you don't fully understand it. The scientific story is still being written. And my point is that the concepts of both information and entropy are themselves useful modelling constructs - extreme simplifications of the world they thus also make usefully measurable by those extreme simplifications.

So - as Friston keenly understood - information theory creates a cleared ground, one stripped of the quality of meaning, so that science could then start constructing the right kind of metric for measuring systems with meaning. Information theory gave you a basis for more complex metrics like mutual information, surprisal, ascendency, or one of the many other formalisations people have been attempting.

ITT could be considered an effort in that direction. But it is too disembodied. Friston flipped things around to talk about free energy minimisation. That was a clever trick along the same lines that biologists used a generation earlier to understand the phenomenon of life as an evolving dissipative structure. The immaterial information was connected to the material dynamics - the self to the world - via an explicit epistemic cut, or modelling relation.

This conclusion aligns with the Zeilinger paper posted earlier. And I think this is the broad direction understanding is headed towards. — Pop

I've returned to biology because so much has been happening there on this issue over the past decade.

And yes, Barbieri is going down this same semiotic track. I would draw attention to this bit...

Genes and proteins are not produced by spontaneous processes in living systems. They are produced by molecular machines that physically stick their subunits together and are therefore manufactured molecules, i.e.molecular artefacts. This in turn means that all biological structures are manufactured, and therefore that the whole of life is artefact-making

This is where the new science is arriving to change the game.

Life can be divided into genetic information and chemistry. But the missing part of the story is how those two realms are mechanically connected.

And exactly the same intellectual journey is under way in neuroscience - as its tackles its good old dualism of mind and body. -

Death Positivity, the Anxiety of Death, and Flight from ItThe point of this little detour is that, if the goal of this movement is to re-evaluate our valuation of death, it probably should try to re-evaluate our value of decay more generally because death is a subset of that... i.e. it should be called the decay-positive movement or something. — ChatteringMonkey

You make an excellent point. And I will add some further complexity that comes from a theoretical biology point of view.

I think two things can be confused here. But they may also be the same thing - being just a difference between going out with a whimper or going out with a bang.

Stan Salthe has defined a canonical lifecycle of an organism in terms of the three stages of immaturity, maturity and senescence. Life is understood as a system of entropy production. An organism is an negentropic structure that arises to breakdown or dissipate a larger entropic flow. And so biology embodies the "paradox" of a struggle to develop and persist as a stable set of habits - a negentropic structure – that efficiently exports enough entropy (or decay) to both survive as that set of habits, and yet not destabilise that set of habits.

So the production of decay is the basis of life. But it has to be exported to an external sink - the unlucky environment - rather than be allowed to erode the useful negentropic structure of the organism itself.

To get back to Salthe's three stages, there is thus a general developmental imperative that we can recognise as the human desire to grow and achieve mastery over the world, and in doing so, become a successfully persisting self. This is an open-ended upward trajectory wired into life by the logic of its origins. It doesn't naturally envision its own death as part of the scheme .... except to the degree that this selfhood is in some strong sense going to be recycled as part of a larger scale of organismic structure, like a family dynasty, cultural community or even reincarnated chain of being.

But I'm jumping ahead. If we stick to the open-ended story of the development of an organism as a unit of dissipatory structure, Salthe argues that immaturity is characterised by vast entropy production - the rapid growth and high consumption of any infant learning to cope and live in the world. The infant is highly plastic, having few established habits, and so prone to making many mistakes. But rapid growth or a high entropy lifestyle also gives the immature organism great powers of recovery. It can suffer big injuries, dreadful errors of judgement, and rebuild back better at speed. Growth papers over mistakes fast.

Maturity is then when growth slows and a store of habits stabilises. The system settles into a routine relation with its environment such that surprises or perturbations are managed to a large degree, and yet still there is enough growth potential to fix decay, or regain ground lost to errors.

But fortunately or unfortunately, the developmental journey must continue to the third stage of senescence - which may be a bad term because it over-emphasises the internal decay aspect. Yet anyway, Salthe's point is that an organism never ceases to strive to be well-fitted to its world in terms of its ability to persist as an entropy producing/entropy exporting structure. And so it keeps developing a greater weight of fixed habits. An organism which was clever in its youth - able to deal creatively to solve the many novel situations that an inexperienced self must face - becomes increasingly wise. The longer you live, the more experiences you have learnt to deal with, and so the less you need to learn. You've long had it all figured out down to the level of automaticism.

Of course, even a long-lived organism can only adapt to the world they have statistically sampled over that lifespan. So some surprise - some environmental insult or perturbation - will catch them out eventually. And because stability of self is fostered by a steady lowering of its the entropy production rate - needing less fuel because the engine has become so efficient in its perfect adaptedness to its world - it will suddenly lack the powers of recovery enjoyed at its early developmental stages. Being wise is also becoming brittle. When something even small breaks, it can cause the whole show to run off the road with a bang.

Salthe's analysis applies across all life in general. Even ecosystems start with explosive weedy growth, move towards mature slower changing forest, and eventually winds up in super-efficient and super-complex food chains like the Amazon rainforest. But then an asteroid hits, or the planet's climate shifts. Perturbations strike from outside the eco-organism's long experience and you get an unexpected death situation.

Heck, this is getting long-winded. But you can see that a naturalistic view of life and death has this double-sidedness. We could celebrate getting old and even a little decrepit because that equates with becoming long-lived enough to become wise and energy efficient. But also, that means becoming more brittle and less able to recover by throwing entropy production and inexperienced creativity at our problems.

We adapt to getting wise but brittle, efficient but low-powered, by become more cautious and risk-avoidant. And that may feel like a bad thing, or a safe thing, depending on your point of view. If you are young - or claim to be young at hear - it might be seen as a dismal prospect. A sad decay of youthful promise. But surveys of the old finds them actually very content as their horizons shrink towards the safe and familiar - or where they have maintained a balance that best matches their life stage in terms of challenging novelty and the ability to recover from mistakes.

To me, this both explains why attitudes to death can seem so different between the young and the old, and says that any philosophising around the issue has to start with recognising there is not one answer that will seem a correct balancing act for all three life stages.

It is tempting to say immaturity is better than senescence, or maturity is the Goldilocks sweetspot. But then each of those stages is itself a balance of plasticity against stability, explosive growth against efficient habit, creative experiment against wise caution. And we have to live through all these stages as a natural and logical succession.

Having said all that, Salthe's canonical lifecycle presumes a materially-closed natural system like the ecology of the Earth that must largely live within the overall entropic budget set by the solar flux - the rising of the sun each morning. And humans of course have constructed a new world based on fossil fuel consumption and the assumption of an equally unlimited environmental sink for the resulting entropy production.

So that is a new deal - one that seems predicated on eternal immaturity, or exponential rates of growth and hence the unrestricted ability to paper over injury.

The prospect of death, or brittleness, or decay, or even old age caution and wisdom, can all look remarkably different to philosophy when considered against that entropic backdrop.

My youth, like many so-called "angry young men", was spent in a kind of reckless abandon. I was wild, prone to celebrate illicit political acts, and somewhat suicidal. This kind of revolt, though, in my opinion, perfectly natural, was indicative of that I had an incapacity to cope with both the fascination with and fear of death. — thewonder

On the one hand, the power to recover from most mistakes was real at that age. There was factually less to fear and potentially more to gain by relative recklessness and experimentation.

On the other hand, modern society promotes eternal immaturity because it guarantees the high entropy production state on which it has become predicated. So being an "angry young man" is a socially-constructed role that unwittingly serves this larger social purpose. Although society itself has continued to evolve to become even more openly consumption driven. The young rebels with nothing to lose have become the young social entrepreneurs with an endless bucketlist of essential acquistions and fancy experiences to tick off.

So it is natural in an ecological sense to be young and embrace risk. It is a modern thing to be part of a rat race where you are exhorted to cram as much as possible into a short life as can be imagined.

Death in that scenario becomes both an existential threat to the self as a shiny capitalistic project and also an escape from a world that has become dominated by just such a project.

The prospect of death produces conflicted feelings because modern society embodies a conflict between the old remembered slower stable rhythms of a solar flux driven era and the new exponential expanding, individually creative, fossil fuel era.

It is because of that we will live and ultimately fail in our quest to liberate ourselves from death that we should consider our limited time here on Earth as exceptionally valuable. Death adds weight to the human experience. — thewonder

This is true. But it is also part of the general social construction. So it becomes an issue with a degree of choice.

Modern society thrives on constructing us as self-actualising individuals. The young entrepreneur has become the highest form of existence in modern culture. And in an exponential growth situation - the world of the technological singularity - this indeed is the social ideal.

But counter to that is a slow-burn senescent social system where individuality its not such a big deal. People feel more part of the overall long-run and largely unchanging succession of birth and death. The sun sets but rises again every day. The fact of death will feel quite different against such a backdrop.

So I'm not saying either attitude is the correct one in some absolutist moral way. My argument is that both are natural to their social contexts, because they construct the kind of individuals who best further the persistence of that social context.

The issue is the deeper one of how long you can actually persist with an exponential rate of growth and entropy production as a society. The new crushing fear of anyone who is young these days must be not the weight of their own distance death from old age but the likely global extinction event about to arrive any time soon.

But as Rupert Read is so good at pointing out, we can't even have open public conversations about that.

Though this post may seem somewhat nihilistic, I would actually slate it in opposition to a fundamental Nihilist precept. Life is not meaningless. The fact of death is the basis from which life has meaning. All forms of so-called acceptance are mere soothsaying phrases to old and tired existential revolutionaries. Death ought to be fought against for as long as we shall live. — thewonder

So what I am trying to say is that the time for such a view has now past. It has been overtaken by a new reality. And it wasn't much relevant to any early reality.

In our most natural state - a hunter/gatherer lifestyle lived to the tune of the solar flux - the lines between the individual and the community, and also between the living and the non-living, were more blurred. Or rather, were socially constructed as a constant and long-run interaction. Death would have carried a weight, but not the kind of romantic and existential weight it started to get with the start of the modern era.

Then when the modern era really cranked up - with the factories and coal fields - there was a shift from the economics of labour to one of consumption. The monetisation of labour led to one kind of social rebellion - the angry young man meme that any boomer was brought up with, and became an avid consumer of. The monetisation of consumption produced its own early response in hippies and greenies, but then was likewise mainstreamed in a positive light as self-actualising yuppies and entrepreneurs.

The culmination of this life positivity or extreme individualism would look to be the Silicon Valley biohacking and singularity meme. Young money believes it will be too smart to die. It will live forever by some tech trick or other.

So life positivity is its own pathology when it out-runs even its own socially-constructed entropic base. Fighting death by cryogenically freezing your head was the dumb thing to do in the 1990s. Modern tech promotes even more nutty elevator pitches today.

It comes down to the tricky question of how individually to view the prospect of your death in today's cultural and entropic circumstances? We are on the Titanic headed towards the big climate change iceberg. We've been assured the ship is unsinkable. Do we jump into the icy water early or stick around to see how the movie ends? Either way, how do we assimilate this global extinction event to our own individualist collection of life projects - that bucketlist of meaningful experiences we were determined to cram in?

Can all these conflicting thoughts be tied up in a neat bow in fact?

As you can see, it is quite an exciting time to be talking about the real meaning of life and death. Never has more been happening on that front. Is the only intelligible life goal these days to aspire to being a witness to the end of human history? (Again, Rupert Read is a delight on this issue). :grin: -

What is Information?You provide me with expressions of your consciousness, that contain integrated information about it, whilst rubbishing me and IIT, all the while your expressions prove you wrong. You have got to laugh? — Pop

I gave you the obvious criticisms of ITT that were made even when Tononi first started going down that route. I remember the rubbishing and even some laughter during the coffee breaks at neuroscience conferences in the mid-1990s.

Then when you stop laughing, you have got to come on board. Information is the way to link things. Think about it. — Pop

The thing to think about is that information theory is merely another model of reality. And it is not merely a model, but one - like the materialism it parallels - that explicitly rules out the formal and final causes that Aristotle attributed to substantial being. So it is a continuation of the reductionist project that gives rise to the standard existential crisis that gives rise to the various responses of dualism, Panpsychism and systems thinking or holism.

This is important here especially as you want to conflate consciousness as a phenomenon that is primarily concerned with formal and final cause, with information theory as a modelling paradigm deliberately set up not to talk about formal and final cause.

The reason information theory is useful to humans is that it allows us to atomise the notion of form just as classical mechanics allowed us to atomise the notion of masses and forces - or material and efficient causes. So just as we can mechanically construct systems that are composed of material atoms, so we can construct machines - like computers and communication devices - that are composed of informational atoms. That is, machines that implement logical structures or iteratively generate rule-based patterns.

And just like Newtonian material reductionism, the modelling leaves out final cause completely. Nature is reduced to being arbitrary and random … because that then gives us human maximum freedom to insert ourselves into the equation as the ones who make machines or computers to serve some purpose we might dream up ourselves.

Formal cause is included in the reductionist paradigm simply as unavoidable laws that constrain the space of constructive possibility. They do limit the action - either as physical law or logical law. But they are also somehow placed outside the reality the model is concerned about - a kind of necessary embarrassment of uncertain metaphysical status.

So information theory works really well as a way for us humans to model our physical reality. It imagines nature in terms of the opportunities for technological invention. We can build devices with any form we can conceive, for any purpose we might desire.

But as a model of nature’s causes, it doesn’t even pretend to be complete. It is deliberately a way of telling the story that maximises the creative possibilities for human engineering and thus gets the natural principles of organismic causality quite wrong much of the time.

And yet here you want to conflate a metaphysically truncated model of reality with the primary phenomenon it is so ill-designed to explain.

You can see why I will continue to laugh at the muddled thinking involved. -

What is Information?All of this is an expression of your consciousness. Note, it is vaguely integrated.

It is integrated information! — Pop

Straw man followed by plain silliness. Yet you seem to want to be taken seriously. -

What is Information?Are you saying that the Planck scale is irrelevant to life and mind? Did they just pop into existence separated from the foundations supporting them? — Pop

Straw man argument. -

What is Information?

Yep.IIT is panpsychist — Pop

Mass - energy - information is the new way forward. — Pop

That particular equivalence applies at the Planck scale. So it has nothing to do with the equivalence scale that actually matters for life and mind.

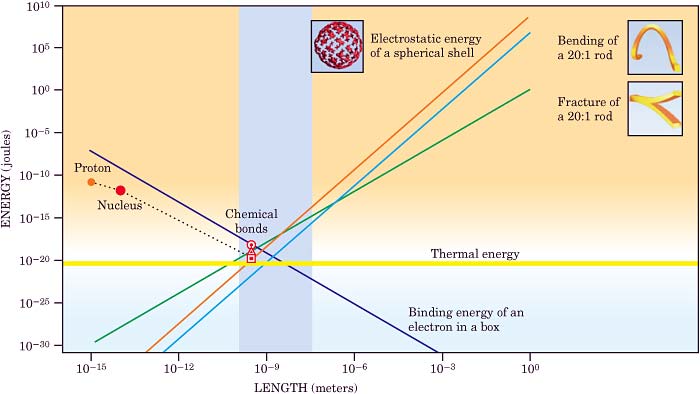

Biology begins at the nano-scale where there is a convergence of all the critical forms of energy that thus creates a "frictionless" mechanical switching of physical actions from one form to another.

Biology (and neurology) is about applying mechanical constraints on physical outcomes. This is why encoded information can have some effect on the world. And - fortuitously it seems - the world just happens to provide a second level where the equivalence principle can apply.

The Planck scale explains the existence of the Cosmos. The convergence of all classical forces at the nanoscale in tepid water is then a further remarkable foundation that accounts for how life and mind could arise as semiotic processes able to control material dynamics.

Phillips, R., & Quake, S. (2006). The Biological Frontier of Physics Physics Today 59

-

What is Information?What on earth are you talking about? — frank

The familiar distinction between the old cogsci approach of the brain as a data display vs the embodied cognition approach where the brain is engaged in a pragmatic modelling relation with the world.

One is dualism rehashed. The other is a triadic systems paradigm. -

What is Information?The statement “everything is information” is also applicable to you. If you cannot provide something that is not information, It follows, everything is information, including consciousness. Note the information in consciousness is integrated. — Pop

All you are demonstrating is that you don't understand your own sources.

Consciousness as a neural process is as much about differentiation as integration. So any simple claim about "quantities of information" is entirely missing the point.

That is why I prefer architectural approaches like Friston, Grossberg and Freeman (to name a few) that positively emphasise the brain's ability to ignore the world - to limit its "information". They get into what is going on at a deeper conceptual level.

Tononi isn't wrong. He just offers the shallow end of the pool story. ITT builds in the faulty psychology of Cartesian representationalism. And that is the bit you have picked up on and presented here. -

What is Information?Telecommunications transmission didn't become digital until the 1960s, so I assume you're using "digital" in a different way. — frank

Yep. The basic distinction goes back a few thousand years to when H.sap stopped counting in terms of "one, a few, a great many". -

What is Information?So here I think the attempt is to avoid a dualism of mind and matter by saying that this modeling perspective doesn't exist separately from the material domain - ' The information a gene, quantum process etc. contains is not ontologically distinguishable from the structure of its components.' — Wayfarer

I'm agreeing that some kind of dualism is needed. And I'm saying science has gone down that road - on its way to the triadic systems view that makes sense of it all.

And I also agree @Pop is doing the opposite of conflating everything that ought to be kept separate. He is using the folk confusions over both quantum theory and information theory to make a simple-minded monist claim where information states = conscious states ... because "information integration", or "information parallelism", or whatever monist hand-waving confusion seems to serve the purpose.

But I think underlying this attempt is the assumption that material substance, or the domain of objects presented in everyday experience, is fundamentally real. — Wayfarer

Again I agree. Materiality sans information dissolves into radical uncertainty, as quantum theory illustrates. We need to return to the original Aristotelean definition of substance as in-formed being - or fluctuation constrained.

He doesn't seem to want to go full idealist, but it's hard to avoid. — Wayfarer

The problem with full idealism is that it is normally just an alternative form of monist substantialism. It is treating the mind as something physically real rather than our term for a systematic, and therefore irreducibly triadic, process.

So idealism is as bad as materialism to the degree it incorporates the idea that one kind of stuff explains things because that stuff happens to have, for some reason or other, substantial properties. Like either material reality, or mental reality.

In challenging hard materialism, quantum theory doesn't then force you to adopt hard idealism. Rather, it shows that reality emerges as an epistemic habit. And modern quantum interpretations - such as ones applying information theory - reflect that directly.

Reality is composed of the definite answers it can give to counterfactual questions. And two dichotomously opposed questions can't logically be asked of the one moment, or one event.

You can ask a particle about its location with infinite precision, but then that rules out asking about the other thing of its momentum.

You can ask a particle if it is still there or has decayed. But then the more frequently you check in to see, the less chance it has to in fact evaporate.

So good old fashioned substantial reality is formed by having this overlay of informational constraint on material uncertainty. And that means the ultimate Planckian grain of Being is based on this logical counterfactuality - the ability to ask the two contrasting questions that are needed to pin the truth of something elemental, like a particle, to some pair of definite measurements.

Zeilinger thinks not: "No, we [need] both concepts. But the distinction between the two is very difficult on a rigorous basis, and maybe that tells us something." Instead, we need to think of reality and information together, with one influencing the other, both remaining consistent with each other.

That's what I'm talking about.

Sounds an awful lot like 'mind' to me. — Wayfarer

And it sounds an awful lot like semiotics, cybernetics, hierarchy theory, etc, to me.

Where you are saying it sounds like a justification for another kind of monist realism, I am saying, yep, that is exactly the kind of irreducibly complex triadic metaphysics that anyone actually wrestling with the problem of "the mind" has already arrived at. -

What is Information?Noise was a known problem before Shannon because their technology was analog. — frank

Sure. But analog signal filtering or analog computation are not revolutionary in the sense of achieving the kind of strict dichotomous separation I'm talking about.

A digital understanding of information turned both noise and signal into definite countable bits - binary degrees of freedom. And then having reduced everything to this same common ground - a mark could be a symbol for a noise, or a symbol for a signal - you could start to build your system back up from an absolutist stance. -

What is Information?At least matter or matter-energy can be defined within a range by physics. The term 'information' is polysemic, meaning it has many different definitions in different contexts. So saying that 'everything is information' is not a meaningful statement, in my view. — Wayfarer

The confusion arises because metaphysics, and hence the natural sciences, must work their way to an answer by the logical structure of a dichotomy. The world must be broken into its complementary aspects.

The popular notion of information is that it is all about messages that convey meanings. Symbols that can be read. So Shannon's big step to a foundational model of information was to make the basic dichotomous distinction between signal and noise. Given some collection of material events - like crackles on a telephone line - what would we characterise as noise just because it was perfectly random as a pattern, and what would we characterise as signal because it was so clearly deliberate and intentional in its structure?

It was a short step from that to a view of information that was simply about the measurement of an environment's total capacity to be marked by discrete or atomistic events. The question was how many definite symbols could some physical system contain - how many binary 1s vs 0s - regardless of whether any meaning (or act of interpretation) was actually attached to such a mark. All marks just became treated as countable noise.

And that turned out to be its own deep question. Quantum theory showed that the classical physical realm had strict "holographic" limits to its carrying capacity. A volume of spacetime contained a finite number of countable degrees of freedom because every physical event or putative mark became a fuzzy uncertainty at the Planck scale. The logical question - "are you a 1 or a 0?" - became impossible to answer past a quantum limit.

So that is all very exciting from the natural science point of view. The whole of physics could be rebuilt on a metaphysics of marks - the smallest scale of definite events or countable degrees of freedom. It was a way to both recognise the underlying quantum nature of existence, and yet also apply the constraints of an emergent classical picture where reality is formed by a material capacity to ask the critical question of a spatiotemporal location - "are you a 1 or a 0?"

You will note how this rather turns the metaphysics of physics on its head, treating the existence of reality as a matter of inquiry. Can even the Universe be certain a binary question has a concrete answer? Well the Planck scale tells us where the countability of nature starts.

And of course, thermodynamics and entropy theory had arrived at the same equations for the same essential reason. The quantum limit of certainty was also the quantum limit of uncertainty, or disorder. So information and entropy were two ways of describing the same general thing.

Physics thus steered talk about information in the direction of talk about marks that were meaningless - or at least meaningful only in the simplest possible way. It developed the information theoretic framework which could measure the Cosmos's raw capacity for definite events - the pure dichotomy of particle and void, a happening or its absence.

And that both avoids the usual popular notion of information as physical marks that have some meaningful message - to an organism or mind - and also paves the way to a scientific account of meaning-making or higher level semiosis. If you have a clear and measurable definition of noise, then you can start to build a matching theory about signals and their interpretation - or organisms and their use of codes.

That is where cybernetics started to make its contribution - Gregory Bateson definition of information as "a difference that makes a difference". And biology generally is showing how organisms are semiotic - Peircean systems of interpretance.

So physics is being revolutionised by just asking the simple question of how does a reality based on quantum uncertainty even start to be organised enough to be considered a play of distinct marks.

This is a view of information that leaves out any receiver of the information. It is moot whether an event or degree of freedom is considered to be random noise or orderly signal as there is no higher meaning or symbolism being attached to the mark. The first step is just to discover the foundational thing of a counterfactual - the starting point of it being even meaningful to ask of anything: "are you a 1 or a 0? A presence or an absence? A something or a nothing?"

And then we can start to build towards a science of semiotics, a science of organismic meaning. This brings us to new basic principles like the epistemic cut, modelling relation, and other elements of biosemiotic theory.

We can recover the other sense of information as not just about countable physical differences, but differences that make a difference to someone as they are symbols being read as part of an exchange of messages.

So the natural sciences might seem to be confused about "information" as a physicalist notion. But in fact, they are breaking things down to be both far more simple, and far more complex, than the general folk notions of what "information" might mean.

Yeah, everything is a self organizing system. And the thing being organized is information. — Pop

... and what the natural sciences can carefully tease apart, folk metaphysics will gleefully smush back into ugly confusion. -

Referring to the unknown.Mostly I like your thinking, but I sense you share with Pattee, a dualistic bias. — Pop

Hah. I used to question Pattee about this dualistic framing. I was was with others like Salthe who stressed a triadic systems approach. But then Pattee became a born again Peircean like the rest of us.

So Pattee was never a substance dualist, and always in the modelling relations camp (given his close connection to Rosen). That ain’t dualism as usually understood. Which is why Pattee had no trouble becoming the leading biosemiotician.

Would Pattee say a Ribosome makes an epistemic cut in regard to an RNA? — Pop

This is exactly the issue I’ve been working on. The cut seems pretty sharp when you are talking about the coded information vs the material product, but in fact we do then have the further issue of precisely how the two sides interact. In some sense, the informational side of life and mind becomes a machinery - a set of switches. While the material side has to become matchingly “switchable”. And it is only over the past decade that biology has been able to see life operating at the nanoscale and understand what all that means in practice.

So yes, too much talk about a cut may draw attention away from the fact that what gets separated also then must interact. Yet the fact of that interaction was always understood, and now it can be observed in the structural biology of the nanoscale.

Nevertheless, it is the case that no symbol vehicle

or symbolic operation can evade physical laws. This means that in spite of the apparent

autonomy of biological information, physical laws impose several conditions on the material

embodiment of the different forms of information. — Pattee

This is true. But codes also evolve towards idealised abstractness. After genes have come the three further levels of semiosis in neurons, words and numbers. Each operates at a further remove from the constraining hand of physics, and so each digs even more deeply into the possibilities of a coded control over physical dissipation.

Simple life became complex life, then human society, and now human techno-existence. The semiosis and its ability to entropify keep stepping up levels.

The dissipation bottleneck will effect everything, without exception. I wonder what obscure insights you might have, apart from the obvious? — Pop

Chiefly that there is no hope of halting the runaway train. The thermodynamic imperative to entropify fossil fuel is so strong that it has formed its own “mind” now. Human society embodies the urge to keep accelerating the energy burning and waste production.

So in terms of semiotics and dissipative structure theory, a political resistance to change is no surprise. If there is an entropy gradient and the intelligence to dissipate it, then the system will keep adapting its order to do just that.

I think future generations are going to be paying for this sort of thinking. They will look back and blame this sort of thinking for the trashing of the earth. This sort of thinking arises from dualism, of course I am as guilty as anybody else, but I would dearly like to promote a different way of thinking. One where mother earth is respected, as a consequence of the way people think about themselves as being at one with the earth and each other ( monism ). — Pop

Earth has seen these catastrophes before. When Cyanobacteria invented the free lunch of photosynthesis, they poisoned the world with oxygen. Near total extinction followed. But then life managed to add oxygen-based respiration to its redox toolkit and a clever balance was restored. One half of life produced O2 as waste, the other produced CO2. And so life got a Gaian grip on the planet’s climate by building in a cybernetic balance of the two critical gases.

So we know that success looks like. As Hans Morowitz pointed out, life as dissipative structure must be open for entropy and closed for materiality. It has to be based on a complete recycling of its own waste, just in the way a rainforest makes its own soil and even rain.

The human system is all about the entropy and does near zero recycling. Why would we expect it to last much longer in any form? Why would it deserve to with such a disregard of basic design principles?

Will big tech save us? I give you as prime examples the marvels of unrepairable Apple phones, the entropic idiocy of bitcoins, and the big oil sponsored ruse of “green hydrogen. :grin: -

Referring to the unknown.Should I just be satisfied with the unknown being these blanks, and leave it at that? — Aidan buk

The problem is in the claim to know as that already presumes cognition has the aim of accurately representing the outside world. All the epistemic quandaries arise because somehow whatever the mind is doing must be a faithful simulation of the reality beyond it, or else cognition is a kind of fiction - an untruth, a failure to correspond, a faulty description or mistaken belief.

But a pragmatic or embodied approach to cognition argues that the mind is a semiotic and action-oriented model of reality. We navigate the world via a self-made realm of signs - an umwelt. We don’t even want to know the thing in itself. We merely want to have some kind of map by which we can coordinate our behaviour and achieve a stable sense of being.

So the problem of knowledge is not about whether the mind knows the world as it objectively is - whatever that could mean. The goal is to operate with a model of the world in a way that seems to work - the chief product being the sense of being a self in a world where our purposes are served, our being is stable, and our uncertainties are minimised.

So we know from psychology that the redness of an apple is a subjective phenomenon. Physics has no colours. And a representationalist approach to cognition or knowledge could make that seem an epistemic crisis.

However being able to read surface reflectance as if it were a set of different hues is a way to make the hidden shapes of things pop out in noisy natural environments. The brain freely invents the experience. And yet the invention is more than useful. We can be super certain that the red apple and the green leaves are separate parts of the same tree even if the reflected wavelengths are almost indistinguishably similar from an energetic point of view.

In my understanding a self is a self organizing system identical to the body of knowledge (derived from information) that creates it, and this body of knowledge extends to a universe of some conception. So a boundary of self is related to the information a self possesses, which extends to the edge of a universe. This would mean that the object ( other ) is also contained within the boundary of self . The other thus becoming an object relative to self, within self, thus no separation possible. — Pop

The epistemic cut approach works better as it doesn’t try to reduce the world to the model anymore than it reduces the model to the world.

The world is the physical realm and so is the entropy rather than the information. A system of sign then connects this physics to workings of an informational model. The advantage here is that we have both the necessary separation - the one that produces a self - and yet also the bridge of a particular interaction. When a mind and world are in a meaningful interaction, the entropy (as information uncertainty) of the one decreases while the entropy of the other (as overall physical disorder) increases.

There is no flow of information or entropy from one side to the other - with all the philosophical confusion that one-sidedness creates. Instead, there is an interaction between a self and the world, an organism and an environment, where each has a specific reciprocal effect. The order in one is increased to the degree the order in the other is dissipated.

Pattee would say a cut ( a separation ) is necessary to separate the knower from the known, and thus maintain a subject object distinction. The counter argument is that a subject / object boundary has not been identified and so the cut is applied arbitrarily. Pattee acknowledges that the cut's location is arbitrary. — Pop

So the cut has been identified. Life and mind are divided from what they model by this contrast between the growth of stability, memory and habit on one side of the equation, and the increase in entropy production on the other.

This semiotic cut allows the boundaries of the self to be flexible - but not arbitrary - across all levels of life and mind. An immune cell works to protect what it identifies as part of the body’s self and dissolve what is deemed to be other.

Then I could carefully protect my favourite coffee cup - treating it as an extension of my self - or carelessly dispose of a beer bottle by smashing it against the nearest wall because I generally regard it and my environment as non-self - a realm of waste, an entropic heat sink. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyAnd the other parts about the origin of the triadic necessity? — schopenhauer1

A relation is irreducibly triadic. Two things must be separated, and they need the third thing of their connection. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomySo you need three to tango, eh? — schopenhauer1

A man, a woman and a song. Can there be a tango with less? Does a tango need more? Can you count to three? -

The Federal ReserveThe Fed’s role is mainly in monetary policy. — Xtrix

I’m just pointing out the political context within which the Fed operates. Technically, the Fed just makes rational decisions about matching money supply to US economic growth targets. But if the cost of money creation is being picked up by the rest of the world, then that explains the irrational - or rather, rationally selfish - monetary policy we saw with the GFC and now repeated with the pandemic.

In monetary policy, the Fed was meant to be the tough cop forcing the market to take its medicine. The theory was that money supply could be controlled in a way to maintain the economy within certain bounds. A small and stable amount of inflation. A bit higher and stable rate of interest or money return. Full employment so no capacity was un-utilised. Sensible stuff that was worth a little pain.

But once the US economy was constructed on the premise of dollar hegemony rather than US economic performance in the world market, this monetary idealism was corrupted at root.

And so the Fed administers a rigged game where the US is also lucky enough that it can walk away from the global order as soon as it crashes. The US can say thanks for the fun guys, nail down a North American pact with cheap Mexican manufacturing and cheap Canadian resources, and do fine in that regional sphere.

The Fed will then have a new political context in which to operate.

Your OP mentioned conspiracy talk and strong sentiment, so I presumed it was the real-politik rather than actual monetary theory that was what you wanted to discuss.

Why did he Fed stun the world by chucking out the textbook and providing unlimited bailouts? Where is the social justice in destroying jobs yet driving up the value of the assets of the wealthy and now even pumping up commodity prices and creating the inflation that will produce still greater levels of inequality?

Whose economy does the Fed even serve? Etc, :grin: -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyIt seems what you are calling phenomenology is entangled in the philosophical presuppositions grounding one or more of these earlier approaches in psychology. — Joshs

My comments reflect who I found to be making sense when I was sorting this out for myself in the l990s. It just happens that reaction time research in sports psychology, Libet’s findings, or 1950s Soviet orientation response work, was far more informative about the neurobiological architecture of consciousness than anything much in philosophy at all.

Whenever I happen to encounter anything labelled phenomenology, it seems a mixture of the obvious and the not terribly relevant. By contrast, Peirce and biosemiosis cut through to the heart of the central causal issue in life and mind science - how to escape dualism via the irreducible triad of semiotics, or the modelling relation.

You already critiqued Friston’s embrace of Freud , which I find significant. — Joshs

I was horrified that Freud should be given any oxygen. But from what I remember, there was nothing particular to disagree with.

Are you more or less fully supportive of Lisa Barrett’s work? — Joshs

Another example of reinventing the wheel. What was obvious to social constructionists eventually became obvious to neuroscientists.

As I said, in terms of “predictive coding0, Stephen Grossberg stood out as a neglected genius. Folk like Rao and Ballard were on the money. Friston was promoting Hinton and his Helmholtz machines, but I found them rather trivial in the sense they were efficient tech with little biological realism.

So on the whole, I felt that enactivism and predictive coding were old hat by the time they became “paradigm shifts”. Same with constructed emotions.

Can you send me a link to a predictive processing writer who also rejects representationalism? The only psychologists I am aware of who reject computational representationalism embrace aspects of phenomenology. — Joshs

The rejection of representationalism and the primacy of anticipation-based processing were obvious from many other lines of evidence. So my interest was in who could cash things out in formal models.

For us, agency is about disposition and action, and not about belief.In this we follow the traditions of American Pragmatism and Continental Phenomenology in their critiques of a belief-oriented, representation-centric, model-building mind, in favor of an action-oriented, affordance-centric, world-navigating mind. The first step on this path is the recognition that organisms have access to ecological information. Take that step, and a whole world opens to you.” — Joshs

Well I agree with this general statement but struggle to understand why Markov boundaries and Bayesian brains are somehow the enemy of such an overview.

But then all this stuff is what I was looking into 25 or 30 years ago. My present focus is on the nanoscale of biology where semiosis itself begins. Neurosemiosis is just one level of the larger biosemiotic story.

Could you give me specific examples of how their models fall short of the predictive processing models you endorse? — Joshs

I was going to do a proper catch up on current mind science later this year. At the moment, I’m focused on life science - the big discoveries there over the past decade. So it is interesting to be reminded of these debates, but I have to be selective about where folk might actually be discussing something new. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyThe image produced is one of the person standing back and placing interpretations on events in the world rather as they may sort objects, by mechanistically applying a pre-existing program. — Joshs

So note how this places perception as after the fact. The world happens. The brain processes it’s sensory inputs. Some state of sensation leads on to a plan of action. Somehow a selfhood - a coherent running point of view - is imposed on the brain’s data crunching.

But the brain is set up to predict its world. This prediction involves two levels - habits or automaticisms, and then attentional level processes. Habits take about a fifth of a second to emit, and attention takes about half second. One is a quick filter because the brain has a prepared local routine, the other is slow as it requires a global reorientation of the brain’s state.

This matters as it explains the temporal nature of experience and highlights that the priority is habit and thoughtless action.

To return a tennis serve demands well drilled habit that can be primed by anticipation of the future location of the ball and the thoughtless movement of the body and racquet before the ball has got there. If the ball takes a bad bounce, even habit needs about 200ms to make an adjustment. Attention lags 500ms behind as it must reconcile a failure of expectation with a memory of what actually happened, and so set the scene for a new anticipatory state. The brain is already adjusting its odds predictor for the next serve, while also prompting the player to gesture unhappily at the poorly maintained court surface as a public explanation of a failure to connect cleanly.

So this is embodiment. It is all about a coordination of a self and a world. It starts with some general set of habits plus some specific state of anticipation - a mix of learnt reactions and whatever plans and intentions resulted from the last attentional reorientation. Then set up to act, we react as thoughtlessly as possible. If something surprising happens, attention deals with the reorientation. But the key is arriving at some new and updated state of self-world relation. Attention isn’t delivering a passive representation. It is itself the generation of a better state of adaptation, intention and preparedness.

And note further that self and the world are two synchronised halves of this relation. A bouncing ball and a swinging racquet are tied together - as physics and information - by the continuity of an intention. The world is being defined as a place where anything could materially happen. The self is a constraint placed on what should ideally happen. The ego is not there to witness an internal display or appearances or impressions. The self is simply the forging of a constantly updating point of view.

If our collection of habits worked, then attention was unneeded and we don’t have to change, remember or add anything . The collection of habits is held stable. But to the degree we were surprised or the tiniest bit out in our automatic response, then there was something to learn and alter.

By the way, the neural networker who got all this back in the 1960s was Stephen Grossberg - the adaptive resonance theory (ART) guy. He realised that memory based processing had the basic problem of a plasticity-stability dilemma. Either it would be too stable to learn, or too good at updating and so prone to catastrophic forgetting.

For this reason, brains would have to divide the load and dichotomise as I describe. It would have to go in one direction and form an extremely enduring level of stereotyped habits, then go just the far the other way in having the complete flexibility of a roving spotlight of attention which treated every moment as something surprising and new.

Perception involves a split between a here and a there. We sense here what is over there. Perception involves an inside and an outside; we sense in here in the body what is out there, outside, ‘external’ to us. I call this the ‘perceptual split’. The here-there generates a gap, the space between the here and the there. This space is supposed to contain everything that exists. — Joshs

So here you have the usual mode of thought where someone is already winding up to reject one pole of a dichotomy by jumping to its other. But the brain itself has to have an architecture that gives voice to both sides of a dichotomy. It needs both the stability of habits and the lability of attention. And it needs different circuits (prefrontal vs striatum) so as to really push both complementary modes of processing.

In the same way, we wind up feeling both extremely in the flow of an embodied self-world relation, and then at times completely detached or disorientated. One kind of self goes with thoughtless habit, the other with a sharp crisis of attentional reorientation. (Was that really the shadow of a burglar at the window? Or am I a silly bugger who imagines things?)

Academia organises itself to find dichotomies and set up opposing camps of thought. But if the dichotomy is a meaningful one, then both views must be right as they form the two bounding extremes of the one complementary relation.

The concept of a static , self-inhering ‘object’ is a very high order abstraction. It is nowhere to be found in the fundamental workings of experience. What is to prevent such a system from seeing the world as nothing but a chaotic blooming buzzing confusion? Because the organism is radically implicative, anticipative. It is wholly oriented toward anticipating the replicative aspects of events( not duplicative; experience never doubles back on itself). It isn’t set this way by some internal gyroscope or other rationalist grounding. — Joshs

So if I say stable habits, you say plastic experience. We have opposing arguments and that is what is culturally expected of us.

But neurobiology tells us that establishing a critical balance between both is what it is about. In terms of selfhood, the contrast is between the world ignoring selfishness of our set of static habits and our world dominated self that becomes reduced to the role of the constantly startled passive spectator of a parade of imposed percepts.

Both are true of the selves that we are. We couldn’t be plastic without having stability as our backdrop. And we couldn’t have a stable set of habits unless there was an attentional machinery to learn some lesson from every error of prediction - every moment where the self-world dichotomy didn’t flow quite as easily as it could.

Talking of the quantity of anything is to start from an entity that is presumed to have a countable aspect to it. — Joshs

Again, here you are winding up to reject the other end of the very dichotomy that you would wish to make your stand on. It is like sitting on the branch you are trying to saw.

Think of a dichotomy in its mathematical guise - a reciprocal relation. We can speak about quality to the degree it ain’t quantity, and vice versa. Quality is 1/quantity, and quantity is 1/quality. They can be a dichotomy - mutually exclusive/jointly exhaustive - because each is the dialectical measure of its “other”.

So you reject a claim of quantification as it plainly means the exact opposite of a quale or ineffable essence. Or whatever kind of Firstness you have in mind.

My reply is if it is indeed exactly opposite, that makes it the other half of the same story. There only is a story as it had two polar extremes to place bookending limits on vague possibility (or actual logical Firstness in the Peircean scheme).

The concept of quantity is a qualitative idealization, a covering over of the relevant pragmatic meaning and significance of an experience by restricting ourselves to staring at it as a dead, self-identical pattern, scheme, entity, object , ‘firstness’ that is measurable and calculable. — Joshs

Yes, let’s heap harsh words on the grave of this dead concept. Let’s ignore the dialectical fact that quality can only exist as something definite, and not vague, to the degree it is not what we could mean by quantity. And therefore our concept of quality proves to depend entirely on that of quantity.

The task for neurobiology is to cash out phenomenology as best it can in physicalist terms. And Friston’s neat trick was to quantify a quality like surprise - a central quality for the habit-attention reasons I explained - and use the maths of thermodynamics to construct a testable, measurable, model from that. Surprisal - a feeling - becomes quantified as physical degrees of freedom. And so a sturdy bridge is built between two modes of human discourse,

I ask you what sits there relatively immobile in your system and you mention automatic subpersonal processes, measurable quantities , fixed habits. You ask me what sits there relatively unchanged in my model and my answer is a absolutely nothing. — Joshs

My approach deals with stability and plasticity as the two poles of the same spectrum. And a good outcome is a system which can go to the extreme in both directions in response to the demands placed upon it.

Put differently, in my approach every moment of experienced time , for every person ( and animal ) not only is utterly new in the world , but occurs into a past which , by being paired with what it occurs into , is an utterly new past. — Joshs

But memory is already anticipation - a constraint on future action. Every passing psychological moment of time is part forecast, past retrospective account, that together serve to trap the “thing in itself” of the perception in space in between.

Peirce had his own way of talking about this that may be instructive - his triad of antecipuum, percipuum, and ponecipuum. :nerd:

See…..

https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10289/9037/NZAP%28Dec2014%29.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

And Legg is a good source on enactivism qua Peirce…

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350088688_Discursive_Habits_Peirce_and_Cognitive_Semiotics

The challenge of understanding the phenomenologies I endorse is seeing how such a radically change and difference oriented thinking allows us to experience stably anticipatable themes in the world , and to do so progressively more effectively — Joshs

The self is the stable centre that can thus be the launch pad of unlimited instability. The common origin of infinite degrees of freedom. Or at least that is the modern cultural version of the self we intend to construct via philosophical positions like phenomenology.

And it is even true that this romantic fiction is pragmatically effective. It’s been working for Western civilisation since the Greek hoplites beat off the Persian hordes. -

The Federal ReserveBut it isn’t the world currency. There are many currencies in the world even today, but certainly in the 40s before the Euro. — Xtrix

If you buy and sell internationally, the deals are done in US dollars. To finance exports to the US market, you have buy treasuries or US debt.

World economics is pegged to the value of the dollar. No one wants to be left holding yuan or roubles. Even euros and yen are a distant second.

The history of Bretton Woods is highly entertaining….especially as the US architect was also probably a Soviet asset.

As early as 1936, Harry Dexter White, who was then a little-known official at the Treasury Department, was planning precisely this sort of conference, with the aim of establishing the dollar as the global unit of account of the entire world, and, very importantly, eliminating the pound sterling as a rival.

They were thinking about how if we manage our financial aid to Britain carefully and control it tightly, we can get Britain through the war, but also simultaneously limit its room for maneuver in the postwar world. It was a conscious effort to force liquidation of the British empire after the war.

The United States offers the world a deal. We will establish a new institution, the IMF, which will provide you with short-term balance of payments support if you get into difficulties. In return for which you promise to forswear competitive devaluation, devaluing your currencies against the US dollar without our approval. The world said that's as good a deal as we’re going to get right now, and they took it.

We still mint the currency in which we issue our debt. We've been issuing quite a bit of it in recent years, and we sell it at tremendous prices. We don't have any great incentive to change the system. When we send a dollar to China for Chinese goods, it basically comes back to us in the form of a near-zero interest loan, which gets recycled through the U.S. financial system to create yet more credit, which we can use to buy more Chinese goods.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/03/14/how-a-soviet-spy-outmaneuvered-john-maynard-keynes-and-ensured-u-s-global-financial-dominance/

The IMF’s own historians have returned a verdict of “still not proven” against White though - https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp00149.pdf

:chin: -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept Dichotomydid you know my old high school friend Zach Hall? — jgill

Never heard of him. :smile:

Checking his publications I see that he was focused down at the molecular biology end and my interest was all at the general systems level. So that’s not such a surprise. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyYou always seem to go back to "Well what is a color?" thing. — schopenhauer1

It is those who argue against physicalism that keep bringing up colour experience as their best case. I’m just happy to take on anyone’s best argument.A complex cause for something is not the thing itself that is happening. — schopenhauer1

Monism is simple. Dualism is a simplicity compounded by a simplicity. It is only with a trichotomous causality that you arrive at actual irreducible complexity worth talking about. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyIt isn’t a question of paying attention to the changing flow via introspection When we move our head , our entire visual field changes, a d the object in front of us now appears via a changed perspective. — Joshs

Isn’t that my point? We don’t even notice saccades as that is noise habitually filtered out. It is already expected from reafference. If the world spins and jerks, we already predict that as a consequence of motor planning. And that then generalises the phenomenology to the point of being selves moving our heads within a fixed external world.

Logic and math would be impossible without this abstraction. The exactness of math derived from the assumption of the persistent self-

identicality over time of objects. From this assumption we derive extension, duration and magnitude. — Joshs

Yes. Generalisation or habits of interpretation are at the basis of semiosis as a way of bringing organisation to confusion or uncertainty. So that starts with genetic and neural abstraction and continues on to human word-based social abstraction and then human number-based technological abstraction. Same thing moving increasingly towards its ultimate Platonic extreme.

In other words , the social begins not with exposure to other persons , but in temporal experience moment to moment. When I am engaged in contact with other persons , the way that I interpret that interaction and the linguistic senses of words and phrases and gestures and norms is unique to me. — Joshs

Well yes. Social semiosis is founded on neurosemiosis. The habits of linguistic self consciousness are founded on the habits of organismic consciousness.

We are embodied selves that then learn the extra displacing trick of thinking about ourselves in a rationalising disembodied way.

I am curious as to your take on Andy Clark. He has made an effort to distance himself from the computational representationalism that characterizes writers like Barrett and Friston. So you support his efforts? — Joshs

I felt he was re-inventing the Vygotskisn wheel. But I also supported him in bringing the constructionist model to a wider audience - the mind science crowd.

It’s interesting to me that you consider philosophies which treat affectivity and temporal transformation as primary to be exemplars of a romantic idealism. Since

that group includes not only the phenomenologists but also social constructionists like Shotter and Gergen, Heidegger and poststructuralist authors such as Foucault , Deleuze and Derrida, I assume you consider all of these as romantics? — Joshs

As I argued in response to the OP, the analysis of all phenomena breaks naturally into a dichotomy of the local and the global, the particular and the general, the discrete and the continuous - the many ways of talking about a hierarchical systems causality.

So the connection is much deeper. Any time humans have to reason about anything, they will arrive as this generalised kind of opposition.

If the enlightenment was all about global general laws or principles - Peirce’s synechism - then romanticism was all about is other of local exceptionalism and independent free choice. Or Peirce’s tychism.

So in the same way, a concern with tychic affect as “other” to synecectic habit, or the temporality of located events vs spaciality of concrete structure, are cultural oppositions that derive from discovering that analysis always results in a dialectical choice.

My criticism is not with the oppositions themselves but with the failure to see through to their triadic synthesis. That is why I push the systems view and Peirce.

I’d also love your response to Dan Zahavi’s phenomenological critique of what he calls the neo-Kantian tendencies of at least some predictive processing models. — Joshs

Just skimming the introduction I see the mistake is in thinking that the task is to predict our perceptions rather than the effect of our actions on the world. So the representationalism stays baked in to those who might think that way about neurobiology. His target is Frith and Metzinger - both of whom failed to impress me in this area.

So my approach - a Peircean semiotic one - is that cognition makes no sense except to the degree it is a material engagement with the world. Our internal representation is an umwelt or an experiencing of the opportunities for meaningful actions. If I see a door knob, my hand is already prepared to grasp and operate it.

So the kind of thing folk were talking about in the 1990s as affordances or deictic coding. Or even back in the cybernetic 1950s with perceptual control theory. Nothing is ever new under the sun.

This is why I stress that our reportable phenomenological experience is all about a semiotic modelling relation that is not merely a model of the world, but a model of ourselves as a free agent standing in contrast to the brute constraints the world might wish to impose.

And then, I stress how even to frame consciousness in terms of reportable phenomena and temporal experiential flows is to bake in the Cartesian representationalism we want to avoid. We want to understand consciousness and selfhood in terms of a collection of well-adapted action habits.

Representationalism makes us passive observers of a world that …. we have internally constructed … for some weird reason no one can explain.

A triadic modellling relation instead is all about how brains are tied into their worlds in real-time by non-stop choices about opportunities and actions.

Representationalism starts with a dark screen and demands it be painted with some particular image. Semiosis starts with the unbound possibility of Firstness and thus sets the opposite problem of how to be able to constrain that overwhelming variety - the blooming, buzzing, confusion - to some focused and rational plan of immediate action.

That is why phenomenology starts on the wrong foot. Representationalism still lurks. The foundational issues haven’t been addressed. To talk of the quality of experience rather than the quantity of information (Friston’s free energy) that can be dissipated, is to show which paradigm still truly has you in its grip. -

A New Paradigm in the Study of ConsciousnessThis isn't your 70's EEG! — Enrique

But the point was that you still employ a 1970s bastardisation of 1950s EEG tech. Brainwaves were already pseudoscience half a century ago. -

The Mathematical/Physical Act-Concept DichotomyThat is to say , the flow or stream of consciousness consists of continuous qualitative novelty moment to moment. — Joshs

But paying attention to fluctuations is a linguistically-scaffolded and socially-constructed human practice. Animals have the same brains but lack the language code to construct a habit of self regulatory introspection.

Animals merely extrospect - live in the flow as habitually as possible with no extra duty to be accountable for every possible “affect”. Human society depends on training individuals to view as independent actors in a socialised context. And so there is this semiotic of affect where we have to give a causal explanation (or excuse) for of every response.

I hit him because I was angry/sad/mistaken/playing a game. Affect is just the currency of this cultural discourse. See Rom Harre’s The Social Construction of thr Emotions or Vygotskian psychology in general.

So for neurobiology, phenomenology is already a semiotic extra. A misunderstanding of consciousness as a process, but one that flows naturally from the socially constructed belief that all experience should be attended and reported.

Affective tonality is never absent from experience , regardless of whether I am having difficulty making sense of the world or not. Feeling is never mindless , — Joshs

That is the cultural myth, the poetic ideal. But I can drive through town without registering or feeling anything particular for long periods in regards to the world.

If you look, you will always find some affect to remark upon. But you don’t actually need to look. And indeed, attempting to be conscious and attentive of well learnt habits is the way to disrupt them and start unlearning them. You never want to be thinking of your golf swing as you are hitting the ball.

What grounds any logic is the valuing that generates it , and values are in turn grounded affectively as qualitative feeling. There is no such thing as affect-free thought , or feeling-free reason. — Joshs

You are heaping on the romantic mythology. :smile: Sure, the brain has a positive match or mismatch feeling in terms of its pattern recognition. We can employ that to recognise our cat or know that we know the right answer to a problem. The neurobiology of this valuing (or orientation response) is well traversed. Certainty and doubt are very broad judgements that all brains need to make. Judgments about mathematical or logical patterns is then a socially constructed specialism built on the general foundation of a capacity for recognising successful pattern fitting.

It's not surprising, then, that Friston chooses Freud's realist model ( Friston's characterization of schizophrenic disturbance as ‘false belief' indicates his realist bent) as a good realization of his neuroscientific project, given that Freud, like Friston, turns autonomy and normativity into a conglomeration of external pushes and internal pulls on a weakly integrated system. — Joshs

Hah. Well it sure as hell surprised me. I spent quite a bit of time with Friston before he formulated his Bayesian Brain story. Out of hundreds of neurobiologists at the time, he already stood out. He knew I was a savage critic of Freud as an old romantic coke head. Yet he never let on he might give the bugger a respectable nod.

By contrast , autonomy for the enactivist isnt the property of a brain box hidden behind a markov blanket, distinguishable not only from the world but from its own body, but the autonomy of a brain-body system, whose elements cannot be separated out and for whom interaction with a world is direct rather than. indirect. — Joshs

I’d have to go back to what Friston wrote in that paper (I only skimmed it with averted eyes). But I don’t think he would have argued against embodied cognition. The depersonalisation and thought intrusion of schizophrenia is a classic example of how the division between self and world is a fluid and constructed boundary. The Bayesian Brain doesn’t just model the world, it models the self in the world. We can chew our food without biting off our tongue because it is all part and parcel of the modelling relation. -

A New Paradigm in the Study of ConsciousnessBrain waves are closely related to states of awareness, reducible to increasingly local behaviors of brain matter which produce unique signatures that blend into the emergent patterns current EEG technology observes. — Enrique

Your precious EEG rhythms are an artefact of a measuring method that offers 1ms temporal resolution but 1cm spatial resolution. So all that alpha, beta, theta, type traces tell you is that the brain is quite busy and contrasty, or relatively quiescent and trance-like. Acting or waiting.

As I’ve already said - and you tellingly ignored - EEG was able to give a certain kind of valuable data in evoked potential work. The 1ms temporal resolution meant you could see that the brain does process information over a characteristic time. The P300 and N400 related to important steps in cognition.