Comments

-

The Univocity and Binary Nature of Truth

But I don't see Thomas saying that the true and the false are not contradictories, nor do I see Aristotle saying that. Classically, true/false are contradictories:

What about the quote from the OP?

I answer that, True and false are opposed as contraries, and not, as some have said, as affirmation and negation [i.e. contradictory]. In proof of which it must be considered that negation neither asserts anything nor determines any subject, and can therefore be said of being as of not-being, for instance not-seeing or not-sitting. But privation asserts nothing, whereas it determines its subject, for it is "negation in a subject," as stated in Metaph. iv, 4: v. 27; for blindness is not said except of one whose nature it is to see. Contraries, however, both assert something and determine the subject, for blackness is a species of color. Falsity asserts something, for a thing is false, as the Philosopher says (Metaph. iv, 27), inasmuch as something is said or seems to be something that it is not, or not to be what it really is. For as truth implies an adequate apprehension of a thing, so falsity implies the contrary.

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/1017.htm#article4

opposite assertions cannot be true at the same time” (Metaph IV 6 1011b13–20)

Yes, something cannot be black and not-black, just as a sentence cannot be true and not-true. This is because being involves contradictory opposition, as does affirmation and negation. For instance, opposing universal and particular assertions would involve negations of each other (i.e. the square of opposition).

Obviously, the truth of a statement often depends on its context. "Peanuts are healthy" is true as respects most men, and false as respects the person with the peanut allergy. Truth and falsity are mutually exclusive in cases where the truth (or falsity) of a statement would both affirm and deny being without qualification (being and non-being are contradictory).

Thomas also says that univocal predication is proper to the discipline of logicians. If you're building a syllogism, then the truth or falsity of your premises vis-a-vis predication should involve contradiction. It would be problematic if they didn't.

I always assumed Thomas's point here was pointing back to Avicenna and ontological truth. There is also truth as adequacy of being to the divine intellect (truth most perfectly) addressed in the prior question (16).

Perhaps you need to define what you mean by "contrary."

Truth represents a perfect adequacy between the intellect and being. Falsity is the absence of this adequacy. If any inadequacy makes a belief or statement false, that seems to be quite problematic. For one, it would mean that all or almost all of the "laws" of the natural sciences are false, along with our scientific claims.

A theory or hypothesis might not perfectly conform to reality, but this doesn't make it completely inadequate either.

Pretty sure you can relate this to the Square of Opposition as well. For instance, "all elephants have big ears” cannot be true at the same time as “no elephants have big ears," but they can both be false. Whereas with "all elephants have big ears" and "some elephants do not have big ears" one must be true and the other false. -

Mathematical platonism

This distinction seems more Kantian than Platonic to me. I think "noumenal" might be a better tern here, i.e. "a thing that exists independently of human senses." At least, Plato himself would reject such a cleavage in reality, as well as existence without any edios (quiddity, intelligibility, form).

Claiming things are real runs into all sorts of prickly problems, though. Have you peeked beyond the veil and seen it was so?

Have you looked on both sides to see if the veil itself is real? I am not sure if you can have a "reality versus appearances" dichotomy if there is only appearances. If there are just appearances, then appearances are reality. But then how do we justify the claim that there is a reality that is completely isolated from appearances?

On the other hand, if we can "infer" the "'reality' behind the veil," then why can't we likewise infer that this reality includes numbers?

This is, BTW, Hegel's critique of Kant. Kant himself is dogmatic. He doesn't justify the assumption that perceptions are of something, that they are in some sense "caused" by noumena (although of course, "cause" itself is phenomenological and so suspect). He just presupposes it and goes from there (and look, he just happens to deduce Aristotle's categories, convenient!). The Logics are pretty much Hegel's attempt to start over without this assumption.

Math is a very useful way of describing relations and ratios between things.

But then wouldn't these objective/noumenal things need to be the sort of things that have ratios? If they don't have ratios, why is it useful to describe them so? If they do, then numbers (multitude and magnitude) seem to apply to the noumena.

Hmm.. I'm inclined to say that there are indeed no objective facts related to chess. Chess tells us nothing about this underlying reality.

But presumably it tells us something about the reality of chess. This is why I don't know about making "objective" and "noumenal" synonyms. For one, it seems likely to me that many people will find a use for the former while rejecting the assumptions that make the latter meaningful. Second, we wouldn't want to have to be committed to the idea that facts about chess, or the game itself, are illusory.

Sort of besides the point though.

I'm actually kind of curious what passages of Plato this refers to.

Platonism in many areas is lower case "p" platonism, which tends to be only ancillary related to Platonism. For instance, :

At least according to the SEP article here, (2) is platonism:

Platonism is the view that there exist such things as abstract objects — where an abstract object is an object that does not exist in space or time and which is therefore entirely non-physical and non-mental.

This could apply to Plato in some sense, but you'd really need a lot of caveats. Plato's metaphysics works on the idea of "vertical" levels to reality. Forms are "more real" they aren't located in some sort of space out of spacetime. But at the same time, even for Plato and the ancient and medieval Platonists, the Forms aren't absent from the realm of appearances. The reason medieval talk of God can be so sensuous without giving offense is because they thought all good, even the good of what merely appears to be good, is still a participation in/possession of the Good.

So, the world of the senses and spacetime would be deeply related to the Forms, not isolated from them. However, I am not super familiar with platonism in contemporary philosophy of mathematics. -

Mathematical platonism

Just as electrons and planets exist independently of us, so do numbers and sets. And just as statements about electrons and planets are made true or false by the objects with which they are concerned and these objects’ perfectly objective properties, so are statements about numbers and sets. Mathematical truths are therefore discovered, not invented.

I know this isn't your definition, but I would suggest a modification to just:

"Platonism about mathematics (or mathematical platonism) is the metaphysical view that there are abstract mathematical objects whose existence is not dependent on us and our language, thought, and practices."

"Independent" might suggest that the two don't interact, but it seems obvious that they must for platonism to be an interesting thesis. The whole second part is problematic in that it seems to assume that "statements" are also independent of us (and true or false independent of us), and I am not sure if all mathematical platonists would like to be committed to those implied premises. It seems to require being a platonist about "statements" in order to be a platonist about any mathematical objects. But, at least for me, "threeness exists without humans around" seems a lot more plausible than "sentences exist without humans around."

I am inclined to argue that maths do not 'exist' in any objective sense.

Math is a product of the human mind, and a very useful for modeling reality for human purposes. It's a way of describing ratios and relations between things. The actual objective nature of such relations seems inaccessible to humans though.

Well, my turn to ask for a definition: what does "objective" mean here? I've noticed it tends to get used in extremely diverse ways. I assume this is not "objective" in the same sense that news is said to be "more or less objective?"

As a follow-up, I would tend to think that the game of chess does not exist independently from the human mind. Chess depends on us; we created it. However, are the rules of chess thus not objective? Are there no objective facts about what constitutes a valid move in chess?

I suppose this gets at the need for a definition.

Isn't it easier then to accept that mathematics does not exist objectively, and is simply a very useful tool conceived by the human mind?

But isn't the follow up question: "why is it useful?" Not all of our inventions end up being useful. In virtue of what is mathematics so useful? Depending on our answer, the platonist might be able to appeal to Occam's razor too. A (relatively) straight-forward explanation for "why is math useful?" is "because mathematical objects are real and instantiated in the world."

This also helps to explain mathematics from a naturalist perspective vis-a-vis its causes. What caused us the create math? Being surrounded by mathematical objects. Why do we have the cognitive skills required to do math? Because math is all around the organism, making the ability to do mathematics adaptive.

1. Human beings exist entirely within spacetime.

2. If there exist any abstract mathematical objects, then they do not exist in spacetime. Therefore, it seems very plausible that:

3. If there exist any abstract mathematical objects, then human beings could not attain knowledge of them. Therefore,

4. If mathematical platonism is correct, then human beings could not attain mathematical knowledge.

5. Human beings have mathematical knowledge. Therefore,

6. Mathematical platonism is not correct.

I think the platonist response would be that premise 2 is false. Mathematical objects exist in spacetime. There is twoness everywhere there are two of something (e.g. in binary solar systems). Premise two seems to imply that any transcendent, Platonic form is absent from what it transcends. Yet this is not how Plato saw things. The Good, for instance, is involved in everything that ever even appears to be good. Plus, my understanding is that many mathematical platonists (lower case p) are immanent realists, along the lines of Aristotle. So, numbers exist precisely where they are instantiated (in space-time). A Hegelian theory would similarly still allow that numbers exist "in history." -

The Univocity and Binary Nature of TruthI will just note that the path from the elimination of analogy vis-a-vis goodness and beauty to total equivocity (extreme relativism or nihilism) is quite similar. Philosophy first removes the option of analogy. It then discovers that a single univocal measure of goodness, truth, or beauty is seemingly impossible. Faced with this result, it has a "slide into multiplicity" and produces a multitude of isolated truths, goods, and beauties, with each varying by culture, individual, or even context.

-

Currently Reading"Philosophy as therapy," has always interested me. There is this neat New Yorker article on it. It would be interesting to me if anyone had ever tried to set up a retreat with this in mind.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/when-philosophers-become-therapists

But then I've been reading about Patristic philosophy, particularly from Syria and Egypt, because this is probably one of the key eras where philosophy is practiced as a sort of therapy on a large scale.

The Philokalia is another great example here, although obviously not focused on the laity. -

Superdeterminism?

Superdeterminism isn't really an interpretation in quantum foundations, like Pilot-Wave or multiple worlds is. Some interpretations are sometimes said to be superdeterministic (e.g. retro-causality, Many Worlds, etc., depends on how you define things though) but the term more often refers to a "theory without a theory," i.e., explaining different sorts of experiments related to entanglement without positing any overarching interpretation of QM.

The benefit here, if you want to champion "common sense" views is that many theories that might fix your "non-conmmmon sense problems," also say some pretty wild things. And you don't want that if you're a champion of common sense, so you remove the part you want and reject the rest.

The difficulty here is that this is not really an explanation or interpretation, so much as a premise just being asserted because it is "more common sense." Of course, what is often meant by this "closer to the classical picture," and we should also question if a view that took so long to emerge is really common sense or not. -

Superdeterminism?

Then Superdeterminists say "yeah but maybe it still works classically, but the reason we're getting the experimental result we're seeing is because *everything in the universe has conspired to trick us into thinking QM is true instead of some type of classical physics*."

:up:, although sometimes the term gets applied to less spurious theories.

One way I've seen it framed is this:

Lots of experiments, particularly modified Wigner's Friend experiments done with photons, seem to suggest that one of:

Locality;

Free Choice; and

The existence of a single set of observations all can agree upon

...must go.

But likely, two of them need to go, or perhaps all three. "Free choice" sounds like the easy one to get rid of. "Ok, but we don't believe in some sort of uncaused free will, easy choice." Except that's not what free choice is. It just refers to the experimenters' choice in making measurements, which can be perfectly "deterministic." To reject this is to say "somehow, through some mysterious mechanism, the universe is set up 'just-so' so that our measurements and observations always correspond to what appears to be non-locality. But really it's because what happens inside an experimenter is somehow causally related (in a directly relevant sense) to whatever their measuring, before they measure anything.

For instance, the spin of a photon you want to measure remotely in a lab 300 miles away, which you didn't even know existed a second ago, is going to determine which property you choose to measure. -

"Potential" as a cosmological origin

Is there a distinction in quantum theory between "nothing" and "nothing-ness?"

The questions: "why existence?" "why the singularity?" or "why cosmic inflation?" is, pace your invocation of "theoretical physicist" (who I am pretty sure does not share your view), and the opinions of most cosmologists, not a "pseudo-question" but something people spend a lot of time theorizing about.

An appeal to physics does not make the answer obvious, certainly not in the way physics can provide solid answers for "why does solid water float in liquid water," or "why are lipids hydrophobic." -

"Potential" as a cosmological origin

Wilzek isn't talking about nothing there, he is talking about the "metric field," space-time.

I have read a bunch of Wilzek's stuff and I have never seen him slip into Davies' unfortunate mistake of trying to explain the existence of existence in terms of quantum fluctuations.

Saying (relatively) empty space-time is unstable is not equivalent with saying nothing, an absence of being, is unstable. The "nothing" in question is most definetly a something. As Wilzek says, "the void weighs."

It would be strange indeed if physics, the science of mobile being, could tell us something about non-being. -

What is meant by the universe being non locally real?

You've mentioned you don't really understand this stuff well, and it shows. Might I recommend perhaps letting go of the rigid commitment to what "science says," until you get a lay of the land. Unless this is supposed to be joke?

Well no, not really. We have evidence and studies for this unlike religion. As for what consciousness is, it's an emergent property of the brain. There is no hard problem to solve here.

Stuff like this kinda makes me question the use of philosophy at times, like trying to complicate matters thatare already solved while offering nothing useful to act on. Science may have started off as such but clearly has come far and distinguished itself since then.

Because, of course there is a problem, it's literally called the "Hard Problem of Conciousness," which cognitive scientists bring up all the time. It has not been "solved." Nor has a satisfactory explanation of emergence, or consensus on if it even really exists, been accepted by most scientists and philosophers. You can find entire academic tomes dedicated to emergence, and many (e.g. the Routledge Handbook) will have to spend hundreds of pages on articles dealing with vagaries and contradictory theories precisely because it isn't something that is "solved."

Nor is "x is emergent" particularly explanatory or unproblematic. What does it mean for something to be "emergent?" Weak emergence as mere data compression, or strong emergence? (And does the latter require getting "something from nothing?" Does it make whatever emerges in some way "fundemental?")

These are all questions scientists and philosophers are still exploring. See: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/properties-emergent/

When scientists work on these issues they end up having to do philosophy. There is no hard line between "philosophy of biology," and biology at any rate. "What is life?" or "are plant and animal species 'real?'" are questions biologists try to answer for instance.

Philosophers sometimes err by straying into areas that they don't understand, but this is equally true for people who work in the natural sciences. E.g., Sapolsky put out an entire book on the "science" of free will, which flops back and forth between bigism and smallism as it suits his argument, and he seems to think that action must be "uncaused" to be free or that any self-determining process must break down into self-determining "parts." There are lots of scientific citations in the book (including lots of unreplicatable, highly questionable stuff, such as the "Lady Macbeth effect,") and he's a scientist, but it isn't good scientific/philosophical reasoning, more an ad hoc mashup of datapoints said to fit an unclear thesis.

This is incredibly common in more theoretical scientific works because you often don't get taught about good argument in undergrad or grad programs in the sciences (at least I didn't). So a lot of popular science seems to mistake lining up an avalanche of citations and referring to how they could fit/be explained by theoretical these, for good argument. This is how you end up with multiple different people who claim to have "solved the Hard Problem" pushing incommensurate theories that nonetheless use all the same landmark studies as their datapoints.

My quote had mentioned the language of "laws of nature." There is also a great deal of debate in the empirical sciences about how to think about these or how to think of causation more generally. There is not consensus here, nor any sort of "common sense," unproblematic definition of what the "laws of nature" are and how they work. And, like I said, it's a language inherited from a theological context and a certain vision of God; the early modern scientists who created our model didn't separate religion and science in the same way. -

What is meant by the universe being non locally real?

It's an interesting question for sure. But against the "information requires consciousness," view we might consider the ways in which information theory informs the biology of algae, viruses, and protists, who I am not sure we want to count as "conscious," even if their behavior is certainly "goal-directed," or "teleonomic."

Plus, if one buys into something like computational theory of mind (long the dominant paradigm in cognitive science) or integrated information theory, then it would seem that information has to come prior to consciousness (else we have a circular explanation).

Of course, pancomputationalism is also very popular with physicists, and this would seem to cut the legs out of CTM, in that literally everything is a computer in some sense, making the brain's "being a computer" not much of an explanation of consciousness.

There is another circularity here. Turing comes up with the Turing Machine model with human computers in mind. Back in his day a "computer" was a person you paid to do calculations. The model is based on what that person needs to do to calculate. The "states" of the Turing Machine are "states of mind" originally. So, we end up explaining consciousness (or all of physics) in terms of a concept whose most popular explanation has a sort of Cartesian homunculus right in the middle of its paradigmatic explanation.

The Shannon-Weaver model of communications also (often) has an implicit Cartesian homunculus in the "destination" that understands any signal in many contexts as well.

IDK, it's a tricky area. I think that the solution is likely to involve seeing that life, consciousness, and goal directedness are not binaries, but exist on a sliding scale (contrary opposition, not contradictory) and that semiotic relations need not involved an "interpreter" just an "interpretant" (e.g. a ribosome doesn't "read.")

Which reminds me of a good quote on this sort of issue:

If we could ask the medieval scientist 'Why, then, do

you talk as if [inanimate objects like rocks had desires]?' he might (for he was always a dialectician) retort with the counter-question, 'But do you intend your language about laws and obedience any more literally than I intend mine about kindly enclyning? Do you really believe that a falling stone is aware of a directive issued to it by some legislator and feels either a moral or a prudential obligation to conform?' We should then have to admit that both ways of expressing are metaphorical. The odd thing is that ours is the more anthropomorphic of the two. To talk as if inanimate bodies had a homing instinct is to bring them no nearer to us than the pigeons; to talk as if they could ' obey laws' is to treat them like men and even like citizens.

But though neither statement can be taken literally, it

does not follow that it makes no difference which is used. On the imaginative and emotional level it makes a great difference whether, with the medievals, we project upon the universe our strivings and desires, or with the moderns, our police-system and our traffic regulations. The old language continually suggests a sort of continuity between merely physical events and our most spiritual aspirations.

C.S. Lewis - The Discarded Image

Of course, theology has had a lasting impact on scientism here, because the move from the universe as an organic whole to one defined by "laws" that are inscrutable, and some initial efficient cause, is not what you get when you simply "strip away superstition," but is rather Reformation theology, whose influence remains potent even in the hands of avowed atheists centuries later. -

What is meant by the universe being non locally real?What's always funny to me is how the classical Newtonian view is held up as the paradigm of "common sense intuitions."

Is it? It's sometimes claimed that classical mechanics "works perfectly" for medium sized objects, and that problems only show up at very large or very small scales.

Except it doesn't. Right from the beginning gravity was an occult force acting at a distance, which in turn had to make "natural laws" active casual agents in the world "shoving the planets into their places like schoolboys" as Hegel puts it. The deficiencies of such a model of causation are well highlighted by Hume. Then electromagnetism added another occult force that didn't fit into the "everything is little billiard balls model."

Nor could/has the mechanistic model, where the billiard ball is the paradigmatic example of all physical interactions, been able to explain life or consciousness, nor was it able to offer up theories of self-organization, except via a deficient view of organisms as simply intricate "clockwork." Nor, in it's classical forms, can it incorporate information and the successes of information theory. We have suggested a long hangover of "Cartesian anxiety," because the classical model required early modern thinkers to excise consciousness, ideas, and freedom from the "physical realm."

I think the "anti-metaphysical movement's" greatest success has been to keep us stuck, frozen with a defunct 19th century metaphysics as the default, such that it becomes "common sense," to most through our education system. But surely it is cannot be "common sense" in any overarching sense, since it differs dramatically from the more organic-focused physics that dominated for two millennia prior to the creation of the classical model. -

What is meant by the universe being non locally real?

From what I see it can’t, especially in this case where the interpretations of quantum physics aren’t even close to the math that is taking place. They’re watered down guesses to explain the math, which is the most solid one ever. But since philosophers commenting on this can’t do the math behind it their works about what it means are effectively useless.

I think this is an unwarranted assumption. Most philosophers of physics are physicists by education and work experience. The ones with philosophy PhDs often also hold undergraduate, or often advanced degrees in physics as well. The top programs for philosophy of biology, physics, etc. often allow candidates to get a masters in the field they are studying now, and of course one can learn the mathematics involved without going through a degree program.

Plus, knowledge of mathematics is not often a limit on contributions to the field. Einstein, largely regarded as the greatest philosopher of physics in the 20th century, had trouble with the math used in SR/GR. He sought help and got it, but he was obviously still crucial to the development of the theory (and obviously so were folks like Robb, the "Euclid of relativity" working more on the math).

Most of the work in quantum foundations—the various interpretations—has been done by physicists at any rate. Philosophers have some important things to contribute though. For instance, the arguments to eternalism from various interpretations of the Andromeda Paradox and Twin Paradoxes, simply involve convoluted reasoning and conflations.

By studying particulars as particulars you get to the unifying stuff.

Right, that's exactly what I said.

Because it is. It’s also funny that you cited two of the weirdos who back it. Wheeler thinks we manifest the universe with consciousness, which we don’t and as a quantum physicist he should know better. Penrose also has wooed theories about consciousness despite what we know about the brain today.

This is an inaccurate description of the participatory universe. At any rate, was the problem with Consciousness Causes Collapse that von Neumann and Wigner didn't know math?

The theory is hard to believe, but it's not prima facie implausible when compared to Many Worlds and the idea that everything happens, nor does MWI seem particularly implausible compared to the premises involved in the superdeterminist view invoked as "saving common sense intuitions."

In a certain sense, the math isn't accurate. The promoters of MWI often stress that their interpretation has the benefit of remaining true to the Schrodinger Equation instead of having to work in "post hoc" collapse. But one has to have a very particular view of mathematics and its relationship to the sciences to claim that having to introduce something that is observed in every case is a knock against a theory.

Likewise, claims of eternalism by physicists, which are incredibly popular in the popular physics literature, often presented as "what science says is true," are going to draw in philosophers because these aren't empirically testable claims and are largely supported by assumptions about how mathematics relates to nature. And if these go a step further into making claims about "free will," that's another place where good philosophical reasoning will be wanted. -

What is meant by the universe being non locally real?

I feel like every new discovery in the field gets muddled by thousands of people who try to run away with it and draw conclusions that it's not saying.

There are quacks and charlatans who use quantum weirdness to push all sorts of nonsense. There are also lots of people who try to label the work of serious scholars as falling into this former category as a way to discredit them and push their own agenda.

For instance, Sabine Hossenfelder portrays retro-causality (and so models like the crystalizing block) as a sort of garble created by uniformed hucksters. It isn't. Hucksters might promote it, but the key work in this area was by John Wheeler and Rodger Penrose, two of the biggest names in the field, and people take it seriously.

It's also a bit strange because Hossenfelder wants "common sense" interpretations of QM, and retro-causality actually achieves this by making the world both local and deterministic.

The confusion is not the result of people doing "bad science." The fact is that there are at least 10 major interpretations of QM and none have majority support. Further, prior consensus was largely enforced by a sort of dogmatic doctrine against work in quantum foundations, including attacks on it as "unscientific." Adam Becker's "What is Real?" has a good introduction on Bell's work on locality and the general climate of intimidation that existed in this period, with people being told explicitly that it was "career suicide" to engage in certain sorts of speculation, or having their jobs threatened, despite this work later becoming extremely influential. Tegmark relates a similar story of intimidation in his "Our Mathematical Universe."

I'm pretty sure physics doesn't really have anything to say about realism, anti-realism, or idealism, but that hasn't stopped folks from trying.

There are many different types of realism. Local realism involves the claim that things indefinitely far away from each other cannot instantaneously affect one another (influence moving faster than the speed of light). People have learned to parrot "but information cannot be transmitted superluminally!" as if this obviously makes entanglement straightforwardly unproblematic. Needless to say, the pioneers of relativity theory, Einstein chief among them, did not think this was in any way obvious.

Coverage of these debates tends towards the consensus that, while Bohr was right and Einstein wrong about "spooky action at a distance," Einstein was right about this being somewhat of a "problem" requiring more attention. Bohr's commitment to a certain sort of philosophy led him to paper over the problem, which in turn discouraged work like Bell's on his famous inequalities.

I don't know how physics couldn't inform philosophical debates or vice versa. It cannot solve them, but empirical examples often play a major role in metaphysics. Physics seems to tell us something about part-whole relations, information transfer, etc.

Physics itself was long a part of philosophy. It's the study of "mobile being," natural philosophy. Plenty of scientists argue there is no clear line between science and philosophy, and I'd tend to agree with them. The idea that the two are totally discrete is just one very particular form of philosophy that was dominant in the mid-20th century, one with thankfully seems to be dying.

The desire to build a firewall between philosophy and science isn't lacking in some good motivation. The logical positivists grew up in the shadow of "Aryan physics" in Germany and "socialist genetics" in Stalin's USSR. But I'd argue that what they really needed was a better philosophy of science that could show them why these fields were not proper scientific subjects.

This problem hasn't gone away. Today we have people positing sui generis "feminist epistemologies" or "African epistemologies," etc. Different sciences for different sorts of people or locations.

The sad thing is, there was already a fine answer to this problem that had been popular for millennia. Aristotle lays it out in the Posterior Analytics and other places. Science deals with per se predications, what is essential to things, not per accidens. This rules out organizing the sciences based on relation (or time/space) because these can involve and infinite number of predications and we cannot consider and infinite number of predicates in a finite time for the same reason that one cannot cross an infinite distance in a finite time at a finite speed. So there can be no science of "biology as studied by men named John" and no "chemistry inside the bodies of cats on the island of Iceland."

Further, there are very many particulars. For example, 200 million insects for each man on Earth. This means science cannot progress by studying particulars as particulars. Rather, it must identify the unifying principles at work in things. For instance, we learn about flight through the principle of lift (and others) not by studying each individual instance of flight or cells in the wings of flying animals. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

I think self-preservation is a drive of nature.

No doubt, but other ends often loom larger. Stinging often kills bees, and yet they sting for the good of the hive. Male spiders, male praying mantis, etc. mate even though this generally means being eaten. Parts of organisms, with their own degree of form and drive to homeostasis, often self-terminate for the good of the whole, and this shows up in individuals in some superorganisms or in holobionts composed of multiple species.

Reproduction and the protection of young is another area where it is common to see even extreme levels of risk taken in pursuit of a goal that lies external to the organism.

Whitehead, in "The Function of Reason" speaks of the three drives:

To live

To live well

To live better

The modern evolutionary synthesis has tended to only focus on reproduction, in part because it is easier to study gene frequencies and model them. Part of what makes extended evolutionary synthesis so fascinating is that it attempts to avoid this reductionism (which is in part only justified by the methodological limits of its time, and then a dogmatic commitment to a particular mechanistic view of nature).

Isn't is sui generis in the sense that it forces us to conceive of "our benefit" in a non-egoistic manner? After all, egoists don't balk at dieting to lose weight in the way they balk at martyrdom.

I don't think so. Any involvement in a common good or deep identification with institutions (e.g. the family, the church, the state, one's workplace, etc.) involves transcending egoism to some degree. One of the reasons the egoist "misses out" on things that are to his benefit is because he cannot fully participate in these common goods.

The good of a "good marriage" or of a deep commitment to the church or one's vocation, can be a key element of human flourishing. The egoist cannot fully participate in these goods. They might get married, but their marriage has to be based around power struggles, manipulation, and quid pro quo arrangements.

Actual participation in the common good, as opposed to merely receiving individual benefits from participation, is not a binary status. People can identify with (even love) and participate in institutions more or less fully. Likewise, Aristotle'sfriendship of the good doesn't require that we don't get the benefits of the friendship of pleasure or the friendship of utility (Ethics Book VIII), but rather than we get the extra benefits of the higher level, which transcends the lower (up to the "giving birth in beauty" of the Symposium—and such "giving birth in beauty" is part of "being like God.")

I agree that we are mistaken in thinking that egoism is the default or natural position, but it does have a basis in human experience.

No doubt. So too does drunkenness, wrathfulness, sullenness, gluttony, licentiousness, adultery, murder, etc.

Egoism is atomization; yet goodness always relates to the whole, pointing to the One as against the slide into the Many.

That's Plato's whole point, that it is the pursuit of what is truly good, not what simply appears to be good or is said to be good, which allows us to transcend current beliefs and desire—to not be ruled over by instinct, appetites, passions, and circumstance (or to be relatively less so).

Egoism is a sort of default that must be transcended. It is the sickness that prevails when good health is not fostered and nurtured. And this jives very well with the Orthodox notion of sin as disease and the Fall as a sort of cosmic corruption, a web of interconnecting, self-reinforcing lines of pathology.

Yes, but the univocity is determined by egoism and the attendant interpretation of "our benefit."

Perhaps. I think there is a sort of positive feedback loop here. Univocity cuts off the option of understanding goodness analogically, which in turn makes it harder to see a coherent way out of egoism, while at the same time egoism makes one blind to the possibility of analogy. A negative side effect of the intense drive towards specialization in philosophy is that there isn't much focus on the ways ideas from different areas of philosophy interact.

This is part of what makes modern ethical treatments of the classical tradition often deficient. They are deflating them out the gate because the moral philosopher doesn't want to mess around with metaphysics and philosophy of nature, and yet for Aristotle notions of virtue ultimately tie back to metaphysics, the "queen of the sciences."

So, I see the two coming from different angles and reinforcing one another. Whereas this is a very different view from the idea that the One is also the Good itself (e.g., https://www.newadvent.org/summa/1006.htm) -

Dare We Say, ‘Thanks for Nothing’?

There will be more of us once we unveil the new Thanksgaining mascot, Pizza the Hutt. People will drop their dry turkey in no time.

-

Dare We Say, ‘Thanks for Nothing’?Truly, we should forget the prayers and thanks and just fully embrace our secular bourgeoisie culture. Rename the damn thing "Thanksgaining." The sales start on Thursday now anyhow, and retail workers have to show up before they've had time to eat any turkey either way.

What should we be thankful for? Getting to gain!

I figure we give people until 2 or 3 in the afternoon to finish gorging themselves on the cornucopia provided by Monsanto and co. and then it's time for shopping! Remember to bring the pepper spray in case someone tries to take the last TV or Xbox you want. :rofl: -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Sure, I just think the extreme cases are useful to demonstrate how it is implausible, from the perspective of almost any ethics, that we always benefit most from extending our own lives. For another thing, dramatic calorie restriction is pretty much the best way to ensure life extension in organisms, and yet very few would want to say we benefit from starving ourselves to get a few extra years of old age, even if we are "gaining years" at the cost of fleeting satiety.

But if we can have proper goals that trump life extension, then it is to our benefit to pursue them, and this can hold for greater sacrifices as well. This can mean self-sacrifice involving death, just as the bee prefers to sting and die rather than to flee the hive. The drive of beings to maintain their own form is absolute nowhere in nature.

We might say that it benefits us to have things we care about so much that we are willing to make such sacrifices. The egoist is, in a certain sense, "missing out" in their inability to so fully identify with things that transcend them.

Nor is the case of dying in this way really sui generis. We often take on all sorts of risk and suffering to accomplish goals. The duties that come with being a parent, learning to ride a bike, learning to read, starting an exercise regime or diet, etc. can all be unpleasant and risky, and yet it seems hard to claim that this entails that they cannot be to our benefit. The daily self-reported "happiness" of parents of young children is significantly lower on average, for years out, but I don't think this makes having children necessarily not to one's benefit.

It's the demand for a univocal measure of the good that leads towards such rigid pronouncements as "it is never to our benefit to do something that kills us." -

Why ought one do that which is good?

I think it particularly makes sense from the perspective of virtue ethics, but I think it will make sense in almost any ethics.

Our lives are finite, so we are not talking death versus immortality, but "dying now" versus "dying somewhat later." To highlight the absurdity that it is "always better to die later," we need only consider the limit situation where everyone and everything we cherish is destroyed, subject to great suffering, etc. and we get just 5 more seconds of life, versus our simply dying, with none of these consequences, 5 second earlier. I don't think anyone wants to be committed to the idea that we should let our children be tortured so that we can take a couple more breaths, or even that those extra few breaths would benefit us. -

Can One Be a Christian if Jesus Didn't Rise

There are two distinct crises, occurring centuries after Origen is dead. The first takes place around 400, during sort of the Patristic golden age and involves a lot of famous characters. The second a century later IIRC. Saint Jerome for instance starts off endorsing Origen and universalism, but ends up attacking some Origenist positions. St. John Chrysostom gets removed from being Archbishop of Constantinople and exiled to Anatolia, in part because he was protecting Origenist monks (although really more because of his clashed with the Empress and her camp). St. Augustine is largely absent from this one because Origenism is mainly popular in the Levant and Egypt, not so much out in Latin western Africa where he is.

The problem with Origen centers around his more Platonist speculations. It would be inaccurate to call them Neoplatonic, because Origen is an older contemporary and potential inspiration for Plotinus, but rather "late middle Platonism." But Neoplatonism might rightly be thought of as in a sense repaganizing Jewish and Christian (including Gnostic) advances in Platonism.

It's worth pointing out that Origen was a critic of the Gnostics, as was Clement, although there is also a lot of overlap because much of Gnosticism became orthodoxy. Pagels argues that John is a "gnostic gospel," which might be a bit much, but there is something to the idea.

A literal 'sky father', then. Origen's writings are voluminous and take some background to understand, but it seems to me he was on the right side of the argument.

I think this probably a gross oversimplification given the characters involved. The main objection I've seen brough up is to the preexistence of human souls and the idea of the Fall as a "fall into corporeality" chiefly. So, the issues at play are the goodness of creation (no doubt corrupted and ruled over by the corrupt archons and demons), and the idea that humans, having achieved the beatific vision and beholding the perfection of God, can decide that something else looks more appealing. I am most familiar with St. Maximus' rebuttal's of these arguments, but the Cappadocians take them up too. The problem is that, if man can achieve theosis and beatification and then fall once, what stops him from doing it again? This also seems to introduce an element of arbitrariness into perfected freedom that is at odds with much classical philosophy.

The other thing is that the views on creation and the fall also tend to make the body a "prison" of sorts, whereas the resurrection of Revelations (less accepted in Origen's time) involves the resurrection of the body. Then, in some places, Origen seems to play around with reincarnation, another "no-go" for otherwise sympathetic voices.

But the issue wasn't so much Origen's speculations, as much later partisans pushing them further and trying to transform them into doctrine and dogma. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Okay, but why? How is it to her benefit? J is obviously going to respond by pointing out that one who ceases to exist can no longer positively benefit.

Because it's generally bad to have one's grandchildren die. The one act, saving the kids, might entail dying. Which is to be preferred? The claim that it is simply impossible to rightly prize any goals more than temporarily extending one's (necessarily finite) mortal life seems like one that it will be very hard to justify.

"A society grows great when men plant trees in whose shade they know they will never sit," is not meant to be a proverb on the benefits of old men falling into delusions about what is truly to their benefit for instance.

"They conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony; love for life did not deter them from death" (Revelation 12:11).

Exactly. As St. Maximus says:

“Food is not evil – but gluttony is.

Childbearing is not evil – but fornication is.

Money is not evil – but avarice is.

Glory is not evil – but vainglory is.

Indeed, there is no evil in existing things – but only in their misuse." -

How do you define good?

Knowing what’s best for me, on a much stricter sense, is an internal necessary truth, carries the implication of an internal authority alone, the escape from which is, of course, quite impossible. Being human, and given a specific theoretical exposition, yes, individuals always know what is best for himself, and he certainly knows what is true, because he alone is the cause of what he knows as best for him.

So what do you think of Plato's response to Protagoras' similar position in the Theaetetus, that philosophers and teachers are worthless if we can never be mistaken about what is best for us?

And how might we explain the ubiquitous human experience of regret, where we think that what we thought was best for us, has turned out (by our own admission) not to be? Is it best for us to drink all those whiskeys when we think it's a great idea at night, and then the same act that was good for us transforms into being bad for us when we wake up with a hangover?

When we throw our life's savings into a crypto scheme and promptly lose it in a rug pull, was the person who told us not invest not more right about what was good for us than we were? -

Why ought one do that which is good?

I don't think that follows --

if it were arbitrary people could agree insofar that they feel the same.

Yes, and they would feel the same at random, according to arbitrary desires, so we should expect overlap to be roughly random.

So, supposing human desire is "arbitrary," why then have I never seen people slamming their hands in their car door for fun or having competitions to see how much paint they can drink? People tend to do a very narrow range of the things they could possibly do. Why do hot tubs sell so well when digging a hole so you can sit in a pool of muddy, fetid, cold water is so much easier and cheaper? Why is murder and rape illegal everywhere, but nowhere has decided to make pears or bronze illegal? What's with people going through such lengths to inject heroin but no one ever inject barbecue sauce, lemon juice, or motor oil?

Sure seems like a lot of similarity for something arbitrary.

The economy -- these are useful for war, agriculture, production, etc.

So then they aren't desired arbitrarily. Science is pursued because it shows us how to do things, indeed, in a certain sense it makes us free to do things that we otherwise could not. At the same time, you also mention wonder. Science is sought for its own sake.

But I'd argue that the desire for truth and understanding is not properly a passion nor an appetite.

But it seems a popular image, at least -- the Rational Being Controlling Emotion. The Charioteer Guiding. There's a part of the image that I like -- that one is along for the ride -- but the part that I do not like is the idea of a charioteer choosing. Taken literally it's a homuncular fallacy -- we explain the mind by assuming a minded person within the mechanism of the mind.

In his A Secular Age Charles Taylor does a pretty great job tracing this to the Reformation period and the rise of "neo-stoicism" and the idea of the "buffered self." So, the overlap with homuncular or "Cartesian theater" theories is no accident. Yet this is decidedly not how Plato was received when Platonism was particularly dominant. Aside from Taylor, C.S. Lewis's The Discarded Image does a good job capturing the old model of the porous self:

The daemons are 'between' us and the gods not only locally and materially but qualitatively as well. Like the impassible gods, they are immortal: like mortal men, they are passible (xiii). Some of them, before they became daemons, lived in terrestrial bodies; were in fact men. That is why Pompey saw Semidei Manes, demigod-ghosts, in the airy region. But this is not true of all daemons. Some, such as Sleep and Love, were never human. From this class an individual daemon (or genius, the standard Latin translation of daemon) is allotted to each human being as his ' witness and guardian' through life (xvi).It would detain us too long here to trace the steps whereby a man's genius, from being an invisible, personal, and external attendant, became his true self, and then his cast of mind, and finally (among the Romantics) his literary or artistic gifts. To understand this process fully would be to grasp that great movement of internalisation, and that consequent aggrandisement of man and desiccation of the outer universe, in which the psychological history of the West has so largely consisted.

Okay, but how so? What is a counterexample?

People ask not to receive medical treatment all the time. My grandfather, for instance, was told he should undergo open heart surgery at 86, after having lost his wife and being ready for the end of life. It is hardly clear that it would have been to his benefit to spend his last days undergoing grueling, painful treatments to extend his life. And this sort of thing happens all the time.

If a grandmother attempts to save her grandchildren, and will die in the process of successfully rescuing them, it hardly seems clear that this cannot be to her benefit either.

Likewise, if a genie shows up and offers us 100 years of the life of our choice in perfect health, or an indeterminant amount of time (but at least 1,000 years) living in a concentration camp, it's hardly obvious that it's to our benefit to take the latter because it extends our lives.

Now you can say, "but people would like to live longer lives, just not sick or imprisoned, etc." And this might well be true, but it shows that life is not ultimately sought for its own sake, but rather as a prerequisite for other goods. -

How do you define good?

Gmak Isn't it the case that good cannot be defined in morality? Only the human actions are good, neutral or evil. But good itself is a word for property of the actions

Not for most ethics. It is things, not acts that are primarily good. One can have a "good car," a "good doctor," a "good government," or a "good person" living a "good life."

An ethics where "moral good" is some sort of distinct property unrelated to these other uses of good and which primarily applies only to human acts seems doomed to failure IMHO, because it cannot explain what this "good" has to do with anything else that is desirable and choice-worthy.

On the prevailing view that dominated in the West for over a millennia, all good things or things that appear good are good in virtue of their possession/participation of the goodness of God, who is goodness itself for example.

For example, St. Augustine' De Doctrina Christiana (Chapter 22):

Among all these things, then, those only are the true objects of enjoyment which we have spoken of as eternal and unchangeable. The rest are for use, that we may be able to arrive at the full enjoyment of the former. We, however, who enjoy and use other things are things ourselves...

Neither ought any one to have joy in himself, if you look at the matter clearly, because no one ought to love even himself for his own sake, but for the sake of Him who is the true object of enjoyment. For a man is never in so good a state as when his whole life is a journey towards the unchangeable life, and his affections are entirely fixed upon that. If, however, he loves himself for his own sake, he does not look at himself in relation to God, but turns his mind in upon himself, and so is not occupied with anything that is unchangeable. And thus he does not enjoy himself at his best, because he is better when his mind is fully fixed upon, and his affections wrapped up in, the unchangeable good, than when he turns from that to enjoy even himself. Wherefore if you ought not to love even yourself for your own sake, but for His in whom your love finds its most worthy object, no other man has a right to be angry if you love him too for God's sake.

-

How do you define good?

I couldn't quite parse what you were trying to say. Is the contention that individuals always know what is best for them and what is true for them vis-á-vis ethics?

You mean like one of these “possible worlds” the postmodern analytical mindset deems so relevant? Dunno about all that pathological nonsense

No, I mean it just in the common sense that we have the potential to be/do things we currently aren't/can't. I can play the guitar and bass. At one point I couldn't, but I obviously had the potential to learn in some sense. I can't play the violin, but potentially I could learn to do so. Likewise, someone who regularly drives drunk could potentially stop doing this, etc. -

How do you define good?

You are welcome to your philosophical inclinations, as anyone is, but obviously they are very far from mine. Not that that’s a problem for either of us, only that there’s little chance of meeting in the middle.

The ubiquitous "bourgeoisie metaphysics" rears it's head again!

But Mww, if someone like St. Augustine, Boethius, or Plato are right, then it is your problem. It is your problem because you are depriving yourself of what is truly best and settling for inferior, counterfeit goods instead of the real deal.

And, we might presume that in your example, it is also the problem of the person whose car you stole :rofl: . But even on a more benign example, a person's friends and family, their employers, employees, and clients, their potentia friends and clients, students, mentees, etc., the state and the organizations of which they are or might be a member—these all suffer when we fail to live up to our potential and do what is truly best because they miss out on what we could be to them. So it's everyone's problem in some sense.

Imagine a world where everyone is their best, most virtuous, strongest, courageous, generous, wisest, enlightened, and self-actualized selves. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

It is always to your benefit to be courageous. (Supposition)

It is never to your benefit to die.

Some courageous acts get you killed.

Therefore, (1) is false. (Via reductio)

Two is a false premise, yet it's easy to imagine an example where something like this might be successful. For example, the courageous fire fighter might die in a scenario where a coward lives, potentially without doing anyone any good through their sacrifice (and indeed hurting their wife and children).

However it would be foolish to think that individual virtue would somehow insulate someone from all bad fortune or all the consequences of living in an unvirtuous world and society. Virtue insulates us from bad fortune and make us relatively more self-determining. It doesn't make us invulnerable and absolutely self-determining. The virtues help us to live better lives, not perfect ones.

In general, it is better to be courageous than reckless or cowardly. In a case where we misjudge the risk as lower than it is, the rash person would seem to always fall victim when the courageous person does, and the converse is true vis-á-vis the coward if the risk is deemed higher than it really is.

But this doesn't mean that we, as people, shouldn't want to be courageous, prudent, wise, etc.—to possess thess qualities in general.

Plus, I feel like courage is the easiest one to make this sort of example for because it involves our response to danger. It's harder to think of common examples where it would be better to be profligate or avaricious, as opposed to generous, or either gluttonous/lustful or anhedonic/sterile as opposed to temperate.

The difficulty of looking at isolated scenarios is the ubiquitous influence of fortune and the unknown. For consequentialists, there is the rape that leads to the conception of the person who invents technologies that remove our reliance on fossil fuels, saving millions from global warming related deaths and preventing several wars. Or the child who is murdered who would otherwise become the next Hitler or Stalin. Or the "life saving" technology developed with the best intentions that ends up harming millions. The same sorts of issues hold true for rules. You either have preverse counter-examples or else create rules so broad and immune to the viccistiudes of fortune and our own ignorance that they are completely unhelpful (e.g. "always choose the better over the worse.")

Fortune and misfortune—error and ignorance, these always play a large role in our lives. Yet the virtuous person is best able to weather them, just as the virtuous state is best able to, be it through better fostering technological advancement, being able to better defend itself, or being more immune to political turmoil and economic disruptions (e.g., people do not tend to revolt against states they love and enjoy and systems they have "bought into"). And of course it's better for individuals, organizations, and states to live in a more virtuous world. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

So this only covers part of ethics then?

Those are just examples. When I think of people who feel genuinely bad about what they have done I am thinking more about documentaries I've seen on prisoners and people I know who went to prison. I don't think BTK or the Gilgo Beach Killer are particularly remorseful. In some sense, they seem incapable of it. -

Currently Reading

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution by Francis Fukuyama

This is a really great work, both volumes, not so much because of Fukuyama's individual contributions, but because it's fairly encyclopedic and is good at synthesizing views on state development. -

Why ought one do that which is good?every wicked person has to be miserable as a result.

But that isn't what is required at all; that would be a straw man relying on extremes (Plato's point, for instance, requires significant nuance). Fortune, the acts of others, the social context, etc. are all relevant to one's happiness. Aristotle makes this point explicitly at the outset of the ethics.

The point is rather that it's always better to possess the virtues than to lack them. "Jeffery Epstein if he never got caught and exposed" being relatively happy (in the common English use of the term), is not a counterexample for two reasons:

First, considering that Epstein was able to build a massive fortune, a great deal of influence, and to be successful in elite social and intellectual circles, it would seem that Epstein did possess many of the virtues to varying degrees. Perhaps luck played an outsized role in his success, but it does seem that he was intelligent, charming, not brash or reckless, prudent in some respects (or we might say cunning), etc.

Second, the proper counterexample would be a case where Epstein lives a better life (or to deflate the notion, is "more happy") and would benefit from being more cowardly or rash, more gluttonous, more irascible or lacking in spirit, or conversely less modest, less temperate, less honest, etc.

The other key point is that the state of virtue involves enjoying right action. Would Epstein's life have been worse if he had enjoyed deeper romantic partnerships based around a common good more than coercing adolescents into sex for his or gratification less? I think the answer is obvious.

The good always relates to the whole. Of course we can imagine a situation where someone who is born into modern Denmark and with great wealth, can, in many ways, live a life that is happier than someone born in Liberia, despite the latter being relatively more virtuous. The virtues, at the individual level, make the individual life better; they don't make context irrelevant.

If the virtues are attained to a high level of perfection (something far more difficult to accomplish in an unvirtuous society), then they do insulate one from future misery (e.g. Laozi and St. Francis happy in the wilderness with nothing, St. Paul sublime in prison).

This is no way entails that "being sent to prison is to one's benefit." It would have been better for Boethius to live in a more virtuous society, one that wouldn't execute him for fighting corruption. It would not have been to his benefit to be less virtuous.

I think it is a better thing for Socrates et al. to do right, but I don't equate this "better" with being beneficial for them; you do.

Ok, but then it seems to me that you're committed to the idea that people can be profoundly wrong about what is truly to their own benefit, because in these examples (Boethius, St. Polycarp, St. Maximus, St. Paul, etc.) all think that would they do is to their benefit. But then if people, and indeed an entire epoch of ethics, can be profoundly wrong about what is actually to their own benefit, then I am not sure what your appeal to "common notions of benefit" is supposed to show exactly.

Which way is the "right" way to use the word?

On the view that things can be truly better or worse for people, the one that is (more) accurate.

It isn't good for people like Epstein to be the type of people they are. It would be better for them to change. Is it good for them to go to prison? Not necessarily, but that's precisely because prison doesn't change the type of person you are. Indeed, it often makes people worse. Prison is often "an education in vice." This has to do with the way prisons work, particularly in the US. It would be better for prisoners if they lived in a more virtuous society that structured corrections better.

No, it says nothing about motivation, and there are many things besides pleasure that are beneficial. It says that a benefit improves a person's lot in life, or something equally general. Again, I appeal to ordinary usage: If one's daughter is raped and murdered, she may have refused to give up a wanted man and been punished accordingly, and so acted virtuously, but what father would claim she had anything beneficial happen to her?

This example is confused, because the daughter is dead, but then doesn't want to give up her murderer? At any rate, you seem to be falling back on "virtues ethics requires you to benefit from being tortured, murdered, etc." again. It doesn't. It requires that you benefit from being virtuous, as in "possessing the virtues" not as in "completing isolated acts deemed good by some deontological framework."

You keep slipping into an entirely alien frame, which is MacIntyre's exact point. You hear "it's to your benefit to be virtuous," and it seems the only meaning you can take from that it "it is to your benefit (personal good) to complete acts deemed morally good according to some set of proper rules by which virtuous behavior is defined."

However, it means: "it is to your benefit to be courageous, temperate, prudent, generous, patient, honest, friendly, modest, loving, witty, etc." and "it is better for you to live with people who have these virtues," and "it is better to live in societies that embody and instill these virtues."

Edit:

I don't think "the best option available" has to be beneficial for anyone; you do.

In virtue of what is an option that benefits no one "best?" -

Why ought one do that which is good?

That's exactly right. Virtue ethics commits you to finding a benefit in virtuous action, and I know it seems weird to you that virtue might not always be its own reward. (Maybe this is a bit of what MacIntyre was pointing to, in terms of the difficulty of building bridges between ethical systems.) But that's not at all the only way to see it.

Yes, but you have said that from your perspective the choices made by Boethius are better for them and "the best option they have available," and that it is better for them. But now you seem to think it is actually better for them to lack the strength of will to follow through on their convictions. Such a view also entails that Socrates, Boethius, etc. are simply wrong about what is truly to their benefit. Egoism is actually to their benefit. They are deluded in thinking it isn't.

As I have pointed out, I find this implausible.

Deontology, as I've summarized it, asks us to ignore this question of self-benefit entirely. Or, if we must talk of benefits, let's stick to the ordinary usage and admire Socrates and Boethius precisely because they chose to forego any benefit for themselves by taking a virtuous course of action.

Right, but now you seem to have stepped back from your previous positions to presupposing "morally good is a sui generis sort of good unrelated to other uses of the term. "

What's the justification for this? Where is the argument for it?

That's exactly right. Virtue ethics commits you to finding a benefit in virtuous action,

No it doesn't. It commits you to the idea that it is better for persons to be virtuous. People possess virtues primarily, not "actions." Actions cannot, for instance, become more self-determining by possessing virtue, nor can they come to more fully know what is truly good as opposed to what merely appears to be good. You keep returning to "virtue ethics as seen through the lens of presuppositions foreign to it."

Or, if we must talk of benefits, let's stick to the ordinary usage and admire Socrates and Boethius precisely because they chose to forego any benefit for themselves by taking a virtuous course of action.

Again, switching back to the focus on individual actions, when the question is "is it to our benefit be a virtuous person." And again, this also presupposes that Socrates and Boethius are both fundamentally deluded as to what is to their own benefit and would benefit from lacking the strength of will to follow through on their delusions.

I don't see how such a position doesn't require the presupposition that "benefit" means something like "egoistic pursuit of one's own pleasure," or something similar. Good luck building an ethics on that assumption, and good luck justifying it, given how many examples there are of people being ruined by such egoistic pursuits.

Or, conversely, this might be resolved as a sort of Protagorean "no one can ever be wrong about what is to their own benefit" position, but this is also implausible.

So, again, this is only a contradiction if we insist on a link between "benefit" and "ethical goodness." From my point of view (which you may not agree with but I hope you will acknowledge is not unreasonable or ignorant), it makes perfect sense to say "It was greatly to Stalin's benefit [or substitute any wicked person who succeeded and died happy] to choose what was worse, that's part of why it was worse -- it was entirely selfish."

No, I'd argue precisely that such actions do represent ignorance. Stalin was ignorant of what was truly to his own benefit. Stalin lived a fairly miserable life, a life defined by constant paranoia and a lack of close relations.

Three stories about Stalin:

One of his son's shot himself in the chest in an attempt to commit suicide and lived. Stalin's first remark was: "I told you he cannot do anything right."

One of Stalin's sons was captured by the Germans. They offered to trade him for a high ranking German officer. Stalin's immediate reply, was a simple: "why would I trade a field marshal for a major?"

Shortly before Stalin had the stroke that would lead to his death he had flown into one of his customary rage and asked to be left alone. Everyone was so completely terrified of him that no one ventured into his chambers until three days later. During that time, Stalin had lain paralyzed and possibly conscious for long periods slowly dying of dehydration because no one was willing to risk his ire by going in to check on him.

Was it to Stalin's benefit to have this sort of relationship with his sons? Was it too his benefit to be a paranoid man who conducted his affairs in such a way that he also had good reason to be constantly paranoid?

Or likewise, was it to the benefit of the BTK killer to stay on the loose murdering and torturing families? More to the point, was it good "for him" to enjoy torturing families much more than a good father? (or was it only "bad for him" because he got caught doing this? Recall, virtue entails enjoying doing what is best.) Or was it to Jeffery Epstein's benefit to do what he did so long as he wasn't caught?

Or would it have been better for each one of these people to be virtuous, well-adjusted people who could partake in the common good of a marriage, family, etc.? I find it very hard to make a case that Stalin or Hitler benefited from being the type of people they were.

Do you think someone like the BTK killer or Jeffery Epstein's main problem was a crisis of intelligibility and sense-making? Or does this only cover part of ethics?

It seems to me that a lot of criminals, in interviews, understand why what they did is wrong at a deep level, and experience significant guilt and shame over it.

Psychopaths like the BTK killer might be a case where there is something of a deficit in an ability to fully recognize what is meant by moral terms or "common good," but in many cases they understand these well enough to do things like have successful careers, stable marriages, be leaders in social organizations, and, obviously, to hide their abhorrent interests and activities.

Certainly, we could fit all this into a totalizing lens of sense-making, in the same way the term "game" is sometimes stretched to incorporate virtually anything.

Plato also at times seems to present a view where all immoral behavior is simply an ability to grasp the full intelligibility of the good, and this can certainly be "made sense of" in his framework, but it always seemed like a weak spot to me. Psychology normally tends to separate an inability to make sense of ethical norms or to empathize and poor impulse control, an inability to emotionally regulate, etc. -

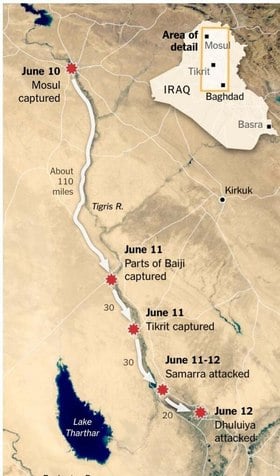

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?

There was a fight in Syria, just not much of one. The rout wasn't particularly different in kind from that the ANA suffered without US support, and that was also in a context where a stalemate had held by agreement with lower levels of conflict for a long period.

Certainly HTS benefited from Turkish support, as other groups that helped depose Assad benefited from US and tacit Israeli support. But the collapse, it would seem, has far more to do with the regimes own issues.

Also, they initially held on a bit, halting the advance at Hama and Homs. Some foreign support began to come in but the US stopped Iranian aligned forces from transiting westwards while Israeli air strikes continued to hit Iranian positions around the country. This probably helped tip the scales towards total collapse, but only because it made it abundantly clear that foreign support wouldn't be forthcoming (and even if it was sent that it wouldn't reach its destination). But at any rate, the ground lines of communication between Syria and Iran were severed quickly by rebels anyhow. -

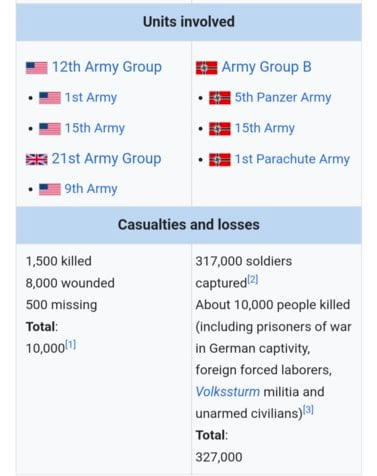

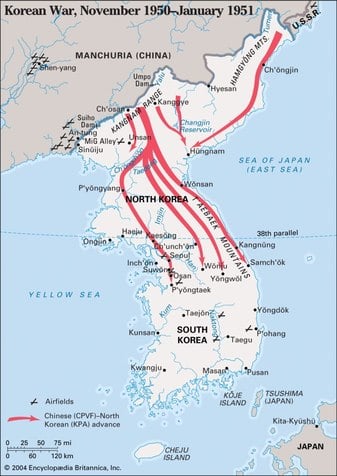

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?

which is ahistorical - armies don't just evaporate under normal wartime circumstances.

Except for:

Afghanistan 2021

South Vietnam 1975

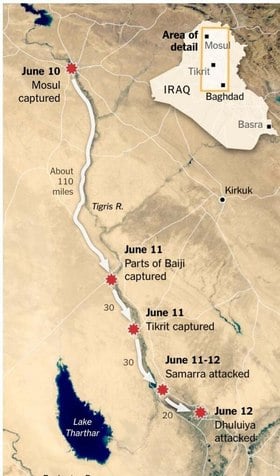

Iraq 1991, 2003, and 2014, see below:

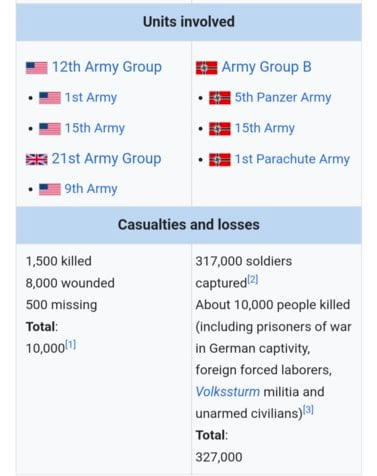

Nazi routs following the Western Allies landings in northern and Southern France, which stopped only when logistical concerns slowed the advance and continued following new offensives with a massively disproportionate casualty rate.

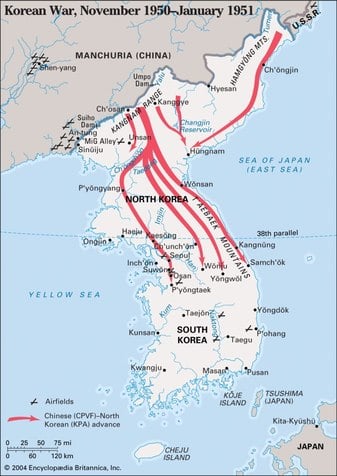

Korea following the Chinese intervention, where the US-led UN force had air, armor, and artillery superiority and had just routed a well-equipped North Korean force.

The extremely rapid fall of France in 1940

The collapse of Russian lines in 1917

The collapse of Russian defensive efforts and routs in 1941, where good order was only re-established outside Moscow and with St. Petersburg under siege.

Or there is the rapid defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, etc. etc. -

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?

The obvious question to ask is how a regime that withstood years of heavy western pressure suddenly crumbles like a crouton, because that already fails the common sense test.

It relied heavily on Russia, Iran, Hezbollah, and other Iranian proxies to survive. Iran and Hezbollah just lost a lopsided war against Israel. Israel, holding all the cards, also forced Hezbollah to sign a cease fire forcing them to withdrawal behind the Litani in Lebanon while still giving Israel carte blanche to bomb them with impunity in Syria if they moved assets there. Iran meanwhile, had ample time to realize their Russian licensed air defense systems are worthless.

Russia meanwhile has lost the better part of a million men in Ukraine and is down to carrying out assaults in passenger cars. Neither could help the Assad regime, who had also demobilized large numbers of troops because they were bankrupt and weren't paying their current troops, who also resented a corrupt, authoritarian, brutal, regime of minority rule.

No conspiracy required really. Assad held on due to a heavy commitment of Russian and Iranian resources and because IS jumped on the scene and took a serious chunk out of the rebels, gobbling up a good deal of their territory and assets, while at the same time drawing the ire of the world and sparking a huge continous air offensive on them by the US and most of the Arab world.

This isn't any more surprising that IS taking Mosul because the Iraqi military routed and driving into the Baghdad suburbs within a week, or the ANA routing in the face of the Taliban. Poorly paid and trained conscripts facing a motivated opposition who don't have much faith in their state tend to rout eventually. A lesson Putin might eventually learn as Tsar Nicholas did. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Nothing in virtue ethics suggests that we need to claim that being tortured "benefits us." This is a creation of your own invention you keep returning to, moving from "it is good to be virtuous," to "it is good to be tortured" seems a bit much, no?

It benefits us to possess the virtues.

So, to make this plausible in cases where by any normal use of language there is no benefit whatsoever, the virtue ethicist has to stipulate the definitions of words like "benefit," "good," and "virtue" so as to reveal that we are mistaken about what benefits us.

What's weird is, you accept that Socrates or Boethius choose the best possible option available to them. But then, on your view, choosing the best possible option doesn't benefit us. We would benefit more from choosing what is worse (e.g. fleeing and escaping for Socrates, or recanting and obsequiously pleading for mercy) in this case.

But your concern here seems to be how we usually use words, and yet we have a case where "it is better/more to our benefit for us to choose what is worse?" and the "worse is better than the better."

Isn't this contradiction in terms more problematic than the claim that we are often mistaken about what is to our benefit?

People thought chattel slavery was to their benefit. Large numbers of Germans thought it was to their benefit to elect Hitler to be their leader. Rapists think raping is to their benefit. Stalin thought purging his officer corps right before trying to reconquer Finland was to his benefit. Putin thought his invasion of Ukraine was to his and Russia's benefit. Many people who started smoking, doing heroin, etc. thought the good/risks outweighed the downside.

I am not sure exactly how this is supposed to be implausible. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Part of what philosophy does is seek the truth. I think that in seeking the truth we find out that the myth of the charioteer is a fantasy born of the ancient's preoccupation with invulnerability -- the invulnerable man could guide the horses, the truly great man would be in control of the self, etc.

Socrates, the hero of the Platonic corpus, is executed by a mob though.

However I think what we learn from psychology is that people do not control themselves in this manner. There isn't a charioteer that's part of the soul, but rather, this is an image to aspire to that no one achieves.