Comments

-

The Nihilsum Concept

One of my favorite topics. We have had similar discussions before (see: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/905552).

is right that Aristotle looks at this quite a bit. One area would be the idea of prime matter as sheer, indeterminate potency with no actuality, no eidos (form), and thus absolutely lacking in any intelligible whatness (quiddity). Aristotle thought that being involved contradictory opposition. Something is either man or not-man, fish or not-fish. Contradictory opposition cannot serve to unify any thing and make it anything at all. But the "transcedental properties of being" in the medieval philosophy that grew out of Aristotle (the Good, the Beautiful, the True, and the One(Unity) all involve contrary opposition. For example, something can be more or less good, more or less unified (for Aristotle too). So the move from being to beings involves this sort of shift in opposition.

Plato's "Chora" in the Timaeus another example. Actually, you can think of the entire philosophical problem of the "One and the Many," which defined ancient Greek thought up to Aristotle, as being very much related to this same sort of interplay between being and nothingness, and the way it collapses our distinctions and ability to say anything about any thing.

Sugrue's lectures on the Parmenides capture this really well. He shows how what Plato is grappling with through the Forms is the slide towards a silent unity in Parmenides (who denies all becoming, all change and motion, and thus must deny all the evidence of the senses—speech collapsing into the one continuous "ohm" of Eastern thought) and the inchoate chaos of Heraclitus' world of ceaseless change, where we cannot say anything true about anything because our words always have different meanings each time we speak them and the things we refer to are constantly slipping into non-being. Obviously, there is overlap with a lot of post-modern and post-structuralist thought here.

There is an analogy to information theory here too. Parmenides unchanging being is like an endless bit string of just 1s (or just the same 1 measured over and over). Lacking any variance, it can hold no information. There is no "difference that can make a difference). By contrast, Heraclitus' inchoate change is more like an entirely random bit string. There is variance, but none of it ever tells us anything about what we can expect in the future, it carries no information (except about its own randomness). Of course, Heraclitus' arguably overcomes this slide into the nothing of unlimited multiplicity and difference with his concept of the Logos. However, in what remains of his work, this Logos concept is not very well developed. What Plato and Aristotle have to do is figure out how to develop this into an actual explanation of how being can be both many and one, to chart a sort of via media through the Syclla of a single, unchanging sound, and the Charybdis of inchoate noise.

Hegel's Logic famously deals with this too (and Hegel is quite the Aristotelian in many ways). The Logic is a bear, but Houlgate's commentary is a bit easier. The Being/Nothing chapter is available here: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://phil880.colinmclear.net/materials/readings/houlgate-being-commentary.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwividrY65yGAxUSJTQIHcJcDJkQFnoECCwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0NPBNROaaCut1CwliwJj6N

Spencer Brown's Laws of Form interesting here too.

To quote from the other thread re information:

If you think about this in analog terms, you can think of a wave with infinite amplitude and infinite frequency. As you increase the frequency, the peaks and troughs begin to cancel each other out. At the point of infinity, you end up with total cancellation, a silence, but this is a pregnant silence. There is perhaps an analogy with quantum information here, where an infinite range between 1 and 0 exists prior to collapse.

So, we have the "pregnant" silence of the infinite wave and the silence of absence where there is no wave at all. This is essentially how Eriugena distinguishes between "nothing on account of privation" and the "nothing on account of excellence" that is God.

Anyhow, a key difficulty that seems to pop up for post-modern thought is the "slide into multiplicity" (as opposed to the slide into the silence of total unity). IMHO, this can be traced back to modern notions of freedom being grounded in potency as opposed to act—the "freedom to do otherwise," or, at the limit, "the freedom to choose anything." This itself grows out of Reformation Era voluntarist theology and the renewal of concerns over the Euthyphro Dilemma (brought on by the univocity of being and the fear that "if God only does what is good" then goodness has become a limit of divine sovereignty). What do largely atheist 20th century philosophers have to do with 15th-17th century theologians? I actually think quite a bit; we inherit our ideas. Hegel is interesting here because he is one of the great rearguard defenders of the classical/medieval view of freedom as "the self-determining/self-organizing capacity to actualize the Good."

This represents in a strong desire to tear down anything definite and actual as a limit to expression and freedom. We can think about the "body without organs" in Antonin Artaud's original sense. There is an important sense in which we aren't free to do anything without our organs. We aren't even free to be an organism, a unity unified by its goals. Without act, there is only the slide into multiplicity, just like language collapses without grammar, syntax, proper spelling, etc. We could consider here how even a 2,000 character short post using a few alphabets and basic mathematical and logical notation has something like 2,000^400+ possible configurations (vastly more than the number of protons in the visible universe by many, many orders of magnitude). Borges' short story "The Library of Babel" illustrates this really well. In the set of all possible 500 page books, almost everything is gibberish (and yet books that decide the gibberish into many different meanings must also exist). -

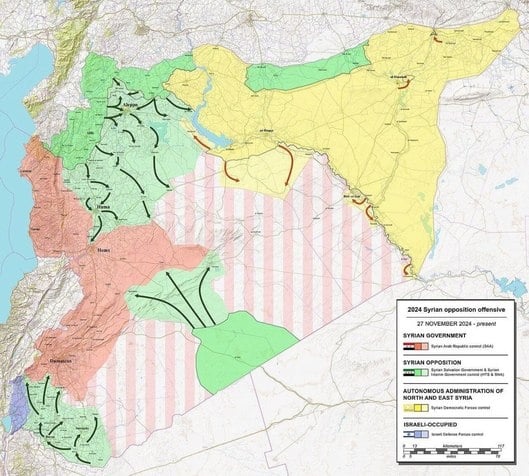

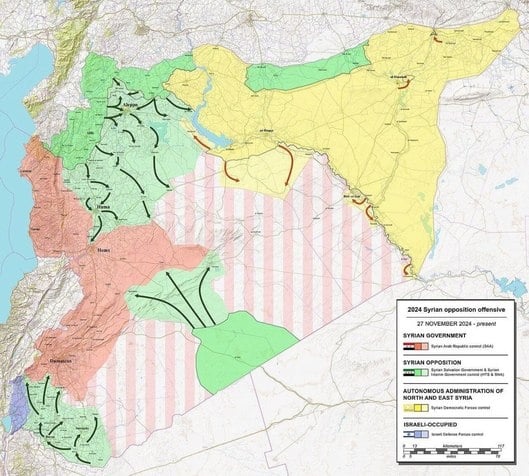

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?Well, the rebels in the south have plowed right into Damascus and are like a 40 minute jog from the center and neighborhoods are mobilizing their own councils/shows of support openly, while the SAA has abandoned their last airport, so it seems like even if Homs somehow held out, it really is finally over.

Videos of soldiers walking away from their posts in Damascus, statues of Assad's father being torn down not far from the centers of regime power, and the presidential palace is being looted.

...and now a mob appears to have publicly hung one of Assad's family members (unconfirmed). I assume he has left at this point. -

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?

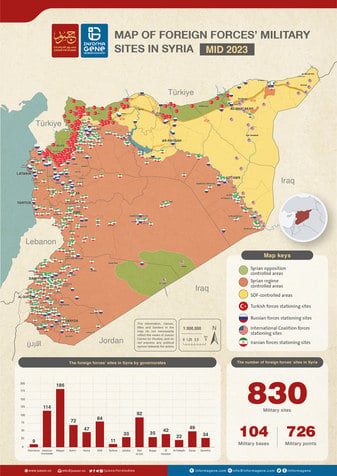

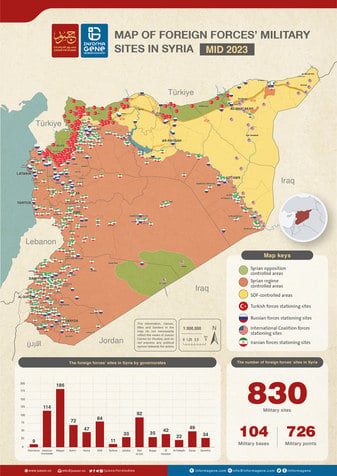

Comparison of what the situation was roughly like for the past long while to since a week and a half ago. Reminds me of the collapse of the Iraqi military when ISIS sprang from Mosul to the Baghdad suburbs, or the ANA when the US pulled out.

Two axes of advance threaten to cut off Damascus from Russia's naval bases, and since they are heavily reliant on them for material this would essentially encircle the Assad regime. The lines of communication will be cut if they take Homs, but they might lose them anyway. Not to mention the population there isn't particularly loyal.

I wonder if this gives Putin any pause as he continues to push low morale conscripts into frontal assault with civilian passenger cars and golf cart style ATVs. Things often break all at once.

An official Russian announcement discussed "meeting with the legitimate opposition to discuss Syria's future," which probably says "it's over" even more than reports that Assad's family has fled to Russia.

Iranian-backed militias have been firing on US bases there and have at times injured US soldiers. According to Central Command these were show of force flights, which doesn't involve attacking anything. They could be lying, but those are very common. Basically, if someone heads your way you buzz them to make them rethink their actions. -

What would an ethical policy toward Syria look like?

It was unclear to me if they might somehow hold on to Homs or not, but given Iran is also openly evacuating its officers and that Assad's family has reportedly fled to Russia, if does seem like it might really be over.

From what I understand the current situation makes defending Damascus extremely difficult, so barring some major reversal Assad would have to flee to Alawite stronghold areas with more defensible geography and people actually motivated to resist. But it's hard to see how, given his failures, he would actually remain the leader of such an Alawite rump state. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

I'm saying he's making an advance in ethical thinking in pointing out how is/ought frequently get conflated as if they have the same import.

I'd say it's question begging sophistry (in precisely the way Plato frames sophistry). To make the distinction is to have already presupposed that there are not facts about what is good. Now, thanks to the theological issues I mentioned earlier in this thread, such a position was already common by Hume's time. It went along with fideism and a sort of anti-rationalism and general backlash against the involvement of philosophy in faith (and so in questions of value), all a century before Hume.

Hume argues to this position by setting up a false dichotomy. Either passions (and we should suppose the appetites) are involved in morality or reason, but not both. Yet I certainly don't think he ever gives a proper explanation of why it can't be both (univocity is a culprit here of course). For most of the history of philosophy, the answer was always both (granted, Hume seems somewhat unaware of much past philosophy, and his successor Nietzsche seems to get his entire view of it from a particularly bad reading of the Phaedo and not much else from Plato).

It's sophistry because it turns philosophy into power relations and dominance. Hume admits as much. "Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions” (T 2.3. 3.4)." This is Socrates fighting with Thacymachus, Protagoras, and that one guy who suggests that "justice" is "whatever we currently prefer" in the Republic (his name escapes me because he has just one line and everyone ignores him, since, were he right, even the sophists would lose, since there is no need for their services when being wrong is impossible). The only difference is that now the struggle is internalized. This certainly goes along with Hume (and Nietzsche's) view of the self as a "bundle of sensations" (or "congress of souls"). Yet, Plato's reply is that this is simply what the soul is like when it is sick, morbid.

Just from the point of view of the philosophy of language it seems pretty far-fetched. Imagine someone yelling:

"Your hair is on fire."

"You are going to be late for work."

"You're hurting her."

"Keep doing that and you'll break the car."

"You forgot to carry the remainder in that calculation."

"You are lying."

"You didn't do what I asked you to."

"That's illegal."

"You're going to hurt yourself doing that."

"There is a typoo in this sentence."

...or any other such statements. There are all fact claims. They are all normally fact claims people make in order to spur some sort of action, and this is precisely because the facts (generally) imply oughts. "Your hair is on fire," implies "put the fire on your head out." And such an ought is justifiable by the appetites (desire to avoid pain), passions (desire to avoid the opinions of others related to be disfigured or seen to be stupid), and reason (the desire to fullfil rationally held goals, which burning alive is rarely conducive to).

At least on the classical view, the division is incoherent. There are facts about what are good or bad for us. To say "x is better than what I have/am, but why ought I seek it?" is incoherent. What is "truly good" is truly good precisely because it is desirable, choice-worthy, what "ought to be chosen" (of course, things can merely appear choice-worthy, just as they can merely appear true). Why should we choose the most truly choice-worthy? We might as well ask why we should prefer truth to falsity, or beauty to ugliness or why 1 is greater than 0.

For the second, could you perhaps say briefly how analogous predication would apply here, in the case of what looks like two usages of "good"? It's quite possible I don't yet understand how that would work.

Short answer: just as the measure of a "good car" differs from the measure of a "good nurse" (the same things do not make them good) the measure of a "good act" or "good event" will differ from that of a "good human being" (and in this case the former are not even things, not discrete unities at all, which is precisely why focusing on them leads to things like analyzing an unending chain of consequences).

I can share a long (but still cursory) explanation when I get to my PC, but the basic idea is that "good" is said many ways. The "good" of a "good car," a "good student," and a/the "good life" are not the same thing. Yet a good car certainly relates to human well-being, as any

More specifically, to make these sorts of comparisons/predications requires a measure. This is in Book 10 and 14 of the Metaphysics I think (and Thomas' commentaries are always helpful). Easiest way to see what a measure is it to see that to speak of a "half meter" or "quarter note" requires some whole by which the reference to multitude is intelligible. Likewise, for "three ducks" to be intelligible one must have a whole duck as the unit measure.

For anything to be any thing is must have some measure of unity. We cannot even tell what the dimensive quantities related to some abstract body are unless that body is somehow set off from "everything else" (i.e., one cannot measure a white triangle on a white background—there are a lot of interesting parallels to information theory in St. Thomas).

I think I already explained Plato's thing about how the "rule of reason" makes us more unified and self-determining (self-determining because we are oriented beyond what already are and have, beyond current beliefs and desires). Next, consider that organisms are proper beings because they have a nature, because they are the source of their own production and movement (not absolutely of course, they are not subsistent). Some non-living systems are self-organizing to some degree (and stars, hurricanes, etc. have "life cycles").The scientific literature on complexity and dissipative, self-organizing systems is decent at picking up on Aristotle here, but largely ignores later Patristic, Islamic, and medieval extensions.

Yet non-living things lack the same unity because they don't have aims (goal-directedness, teleonomy) unifying their parts (human institutions do).

The goodness for organisms is tightly related to their unity. In general, it is not good for an organism to lose its unity and die. "Ok, but sometimes they do this on purpose, bees sting and stinging kills them."

Exactly! Because what ultimately drives an organism is its goals. Brutes can't ask what is "truly good" but they can pursue ends that lie beyond them. And note, bees sacrifice themselves because they are oriented towards the whole, just as Boethius and Socrates do. This is because goodness always relates to the whole (because of this tight relationship with unity).

So to return to how goodness is said in many ways, goodness is said as respect to a measure. The measure of a "good house" is a house fulfilling it ends (artifacts are a little tricky though since they lack intrinsic aims and essences; people want different things in a house). The measure of the "good duck" is the paradigmatic flourishing duck (no need to posit independent forms existing apart from particulars here BTW).

Because equivocity is so rampant in our day, essentially the norm, let's not use "good person." Let's use "excellent person." The excellent person has perfected all the human excellences, the virtues. "It is good for you to be excellent." Or "it is excellent for you to be good." In either case the measure for "you," as a human, is human excellence, flourishing.

But because reason is transcedent, we can aim at "the best thing possible," which is to be like God. God wants nothing, lacks nothing, and fears nothing. Yet God is not indifferent to creatures, for a few reasons but the most obvious is that the "best" lack no good, and love is one of these.

God can also just be the rational limit case of perfection, having the best life conceivable. We might miss much in this deflation, but it still works.

We want to be the best person and live the best life possible. At the same time, goodness always relates to the whole, to unity. No doubt, we can usefully predicate "good" of events, but this goodness is parasitic on things. There is no good or bad in a godless world without any organisms (anything directed by aims). You can't have goodness without wholes with aims.

The predication vis-á-vis some good event has to be analagous because nothing can be "good for an event." The event is good or bad for some thing, according to its measure.

In the 19th century there were many competing theories of heat and electromagnetism. There was phlogiston, caloric, aether, etc. Are we best of returning to the specific, isolated theories, or looking at how what is good in each can be unified?

You might say "but the natural sciences are different, they make progress." And I would agree. It's easier to make progress when one studies less general principles. Yet they don't always make progress. Recall the Nazi's "Aryan physics" or Stalin's "communist genetics." The natural sciences can backslide into bad ideas and blind allies. It is easier for philosophy to do so. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient Reason

Yes, the "intellect as a whole" as the image of the cosmos versus "the mathematical model." -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Yes, this is the sort of thing we want to be true, and it’s very poetically expressed. But at this point one really has to stop and say, “But what do you mean? If you can’t explain what it means without images of spirals and fractals, aren’t I entitled to wonder if it’s actually (rationally) explicable at all?” For, when all’s said and done, I’m still left with what appear to be two quite different usages of “good,” and the desire, but not the means, to unite them. Simply asserting their union won’t do.

I very much want “the Good” to be univocal, and all the uses of “good” to be instances of the same thing, so that “moral good” would not be sui generis in a worrisome sense, any more than “aesthetic good” would be. But . . . the problem is that, IMO, you haven’t yet shown how it can be the case. Perhaps no one can, but we have to do more than assert what I’ve been calling a “metaphysical union of goods” but not explain how it

Two things:

First, it seems like you keep ignoring the option of analagous predication here, but have you given an argument for why it is implausible?

Second, it possible that the demand that everything be reduced to univocal predication part of the problem? Univocal predication is proper to logic. Starting with Descartes, there is an increasing attempt to reduce philosophy to logic and mathematics. This doesn't work. For example, when Sam Harris tries to lay out an ethics that is, in some key respects, quite close to Aristotle and St. Thomas, the project founders on the problem of univocity.

Harris has to wonder about "moral paradoxes" that arise from trying to maximize either average well-being or total well-being. They are interesting, but do we really think human flourishing and goodness are the types of things that can be summed up? To sum something or to take a mean of it is to have already made it a multitude. This is why Harris is able to offer little more than the conviction that we can muddle through such paradoxes, and fairly unconvincing attempts to solve collective action problems, prisoner's dilemmas, etc. using appeals to the observation that "fairness activates reward centers in the brain" in some highly controlled, large sample studies.

This gets back to Banno's idea of a "moral calculus," by which we sum things up and get, I would assume, a numerical value of how good they are. And the idea of some sort of database of rules all rational agents should agree too seems if anything more of a stretch because it seems to ignore the social and historical contextuality of the Good in human life, particularly as expressed in the common good.

But if the good is what "all aims seek," and aims are what allow us (and all things) to become more truly unified, more truly "one," then the good always relates to the whole, and it cannot be anything but an analagous principle because the Good is an extremely general principle (the most general for Aristotle). This is for the same reason that there cannot be one univocal measure of life for all organisms, and yet there are not multiple sui generis lifes (plural) either.

Perhaps no one can, but we have to do more than assert what I’ve been calling a “metaphysical union of goods” but not explain how it works in a way that defeats the objections I’ve raised so far.

But this is precisely what the Physics and Metaphysics (and St. Thomas' respective commentaries on them) argues to (building off the general argument of how the Good is involved in self-determination across the Platonic corpus). It isn't just asserted. If one takes a developmental view of the Aristotlean corpus, this isn't where he started, it's where he ended up.

It just happens that the explanation is also what grounds the sciences and explains discursive reasoning.

How in the world can execution be good for Socrates? Better than the alternatives, sure, but good? You can’t just fold the two meanings of “good” together by fiat, and say that because Socrates has made a good choice, has done a virtuous thing, it therefore automatically becomes good for him. That is what we want for a conclusion, but we lack the argument.

First, you're returning back to "all fortune is good fortune." We need not affirm this to affirm the classical view of the good (Aristotle doesn't ), so we need not affirm that being executed or tortured is "good for you."

Although if something is the "best of all options," then it also has something good about it, no? Do we need to say that something is "the best possible" for it to be good at all?

Second, "being good" is most properly said of beings, not things beings do, and certainly not things they do rarely. Goodness relates to the whole. The measure of a good life is a life, not a sum of moments. Recall Solon and ben Sirach: "count no man happy until he is dead."

You keep pivoting from the whole to the part. This is a different sort of "slide into multiplicity." At the very least, this is unhelpful for understanding the ancients.

I'd argue that it's unhelpful for ethics as well. Trying to generate rules for isolated acts, or calculate the good derived from the consequences of different isolated moments is unhelpful. We can consider the example of the Persian street urchin for whom being unjustly maimed was the "best thing that ever happened to him," or the Frenchman whose rare just act "ruined his whole life."

Plus, if we look at isolated acts, being executed sometimes is good for someone. It might be better to be executed than live in a state of terrible suffering. Just assume that if Socrates had been found innocent he'd catch a disease a week after he would have been executed and would then die a particularly excruciating and drawn out death.

If we say "but surely it is better to live and not be subject to immense suffering," then why not say "it's always better to have what is truly best?" But what is truly best for an individual is going to involve what is truly best for the whole world, and so the focus on isolated acts with break down here anyhow.

To be sure, we can usefully speak of good and bad acts. It is probably most useful to speak of these in terms of what generally follows from them though, the unifying principles at work in them. Otherwise we will be stuck tracing down an endless line of causes tied to some specific act, a butterfly effect by which our decision to cheat on our wife today prevents a genocide 180 years from now.

Rules have the same problem if they are rigidly applied. We either have rules that sometimes seem to force us to do obviously bad things, like turning people over to the SS because we "should never lie," or we end up caveating them so much to avoid preverse outcomes that we might as well just make them general advice, with the true rule being "strive to be the best you can be." -

Why ought one do that which is good?

"Because it's good for you", sure -- but which one?

Well, for this you need metaphysics to explain why the Good is a principle and why we should think it is a unified principle.

Do Stoicism, Platonism, Aristotelianism, Christianity, Taoism, Confucianism, and Epicureanism all have totally different views of what is good? It doesn't seem to me that they do; there is a lot of overlap. So, we might assume some unity there.

Certainly, the Patristics didn't seem to think "the philosophers," had a totally different idea of goodness from that of Christianity. "All truth is God's truth," after all. Sometimes Pope Francis's: "All religions are paths to God. I will use an analogy, they are like different languages that express the divine." is taken to be an arch post-modern hersey, but it's simply the same Logos universalism that has been around since the Church Fathers, and which is enshrined in the Catechism (also, better apologetics than calling people infidels or pagans).

Presumably, there is some way to decide between "is statements," else knowledge is impossible. And there are also arguments that we might say warrant more of less credence, while being far from certain.

The issue of "choice" to me is simply embarking seriously on any ethical life and the life of philosophy itself. As St. Augustine and St. Anselm say, we must "have faith that we might understand," since no practical theory of the ethical life will be fully apparent to us at first glance.

Also, I feel I should note that no one in the classical tradition says that everyone should be contemplatives. St. Thomas and the anonymous "Cloud of Unknowing" say specifically that this is not so. Only a few people have the temperament and aptitude for this path, and not all can follow it even if they do due to other demands and responsibilities. St. Augustine turns away a potential monastic because he is a high ranking Roman military official and is needed there.

The other thing is that the heights of contemplation are not attained through discursive reason. This ties in to classical theories of knowledge. In the Ad Thelassium, St. Maximus goes into depth about how direct experience is superior to discursive reasoning (using I Corinthians to justify this). St. Thomas even has a chapter in the Summa Contra Gentiles that is titled something like: "Why the Happiness of Man is Not Knowledge of God had by Demonstration." By contemplation is meant something like "mystical illumination," and this was often had by people in the "active life" (e.g. St. Francis's vision of the seraphim).

The life of philosophy is adjacent to and supports the life of contemplation, but contemplation is something the laity can engage in. On some views, the entire point of the liturgy is contemplation (e.g. the modern Catholic "liturgical movement.)

On a related note, St. Palladius's "Saying of the Desert Fathers," opens with a story like this. Three saints are together and leave to go do good in the world. One is given the gift of healing and heals. One is given the gift of teaching and teaches. They do this for many years. Yet both eventually grow discouraged because death and dishonesty still abound in the fallen world.

The last saint went out to the desert to pray for the world in solitude. Years later, the other two come to join him, both beaten down by the world. He tells them to stir the well he has dug and look inside. They do, and all they can see is the clouds of dirt, a sea of small granules obscuring everything.

He tells them to wait, and an hour later asks them to look again. This time they can see clear to the bottom, and the light of the Sun is clearly reflected, allowing them to see themselves.

"So it is with the spirit is the moral." To see both the light of God and the inner self requires stillness, hesychasm. But the other moral is that even the hermit ends up helping people, and it's the same way in St. Athanasius' St. Anthony the Great and other hermit stories. There is no fully contemplative life, it's always active as well, because eros leads up and agape pours down. -

How do you define good?

Harris gets some crucial things right. However, he knows he has serious problems. In particular he:

-Wants to define science broadly such that it is continuous with philosophy. This certainly justifiable, but then he has no theory for how the sciences hang together and form a unity. This is a problem, particularly because different sciences have different measures that are roughly analogous to "goodness." For instance, medicine has health and economics has utility, but people often derive utility from things that are bad for their health, and it is not always obvious which metric is to be preferred.

-He equivocates on what he means by "science" so as to exclude philosophy he doesn't like from consideration (also a general tendency to rely on incredulity rather than actually making arguments).

-Has no real answer to collective action problems, prisoners' dilemmas, or free rider problems, which are all over ethics, because he has any such unifying vision of well-being, goodness, and the sciences. Hence, he has trouble explaining why it is good to be virtuous.

-His exclusion of freedom on incredibly flimsy grounds (i.e. freedom must mean "uncaused action" and something like substance dualism), robs him of the ability to explain why virtue is good and some "forms of well-being" deeper, because they lead to self-determination. Self-determination is, however, a prerequisite for actually turning moral philosophy into real action.

I think his project could really benefit from reading Aristotle and even more so St. Thomas, but given his prejudices, that seems unlikely.

I'm actually writing a paper on this because, from my experience in government, it seems that something like Harris view is dominant amongst policymakers and economists (less the religious bigotry, which most don't share). Yet there is a lot in Harris that is said better in earlier thought.

Harris makes a lot of excellent points:

My critics have been especially exercised over the subtitle of my book, “how science can determine human values.” The charge is that I haven’t actually used science to determine the foundational value (well-being) upon which my proffered science of morality would rest. Rather, I have just assumed that well-being is a value, and this move is both unscientific and question-begging. Here is Blackford:

If we presuppose the well-being of conscious creatures as a fundamental value, much else may fall into place, but that initial presupposition does not come from science. It is not an empirical finding… Harris is highly critical of the claim, associated with Hume, that we cannot derive an “ought” solely from an “is” – without starting with people’s actual values and desires. He is, however, no more successful in deriving “ought” from “is” than anyone else has ever been. The whole intellectual system of The Moral Landscape depends on an “ought” being built into its foundations.

Again, the same can be said about medicine, or science as a whole. As I point out in my book, science is based on values that must be presupposed—like the desire to understand the universe, a respect for evidence and logical coherence, etc. One who doesn’t share these values cannot do science. But nor can he attack the presuppositions of science in a way that anyone should find compelling. Scientists need not apologize for presupposing the value of evidence, nor does this presupposition render science unscientific. In my book, I argue that the value of well-being—specifically the value of avoiding the worst possible misery for everyone—is on the same footing. There is no problem in presupposing that the worst possible misery for everyone is bad and worth avoiding and that normative morality consists, at an absolute minimum, in acting so as to avoid it. To say that the worst possible misery for everyone is “bad” is, on my account, like saying that an argument that contradicts itself is “illogical.” Our spade is turned. Anyone who says it isn’t simply isn’t making sense. The fatal flaw that Blackford claims to have found in my view of morality could just as well be located in science as a whole—or reason generally. Our “oughts” are built right into the foundations. We need not apologize for pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps in this way. It is far better than pulling ourselves down by them.

Yet he sometimes makes them very poorly, and St. Thomas is the prime candidate I can think of who makes this same point far more lucidly and in the context of an incredibly tight system. -

In defence of the Principle of Sufficient ReasonI'll just share Kenneth Gallagher's metaphysical (as opposed to nomic/physical necessity) principle of causation vis-a-vis mobile being:

For no being insofar as it is changing is its own ground of being. Every state of a changing being is contingent: it was not a moment ago and will not be a moment from now. Therefore the grasping of a being as changing is the grasping of it as not intelligible in itself-as essentially referred to something other than itself.

Kenneth Gallagher - The Philosophy of Knowledge -

Why ought one do that which is good?

If you are good, it will be good for you, you will experience something that you perceive as good.” And you’ve been reading it as “It is morally more desirable for you to be a good person.”

I would tend to disagree with both. It is not always good for us to have what we "perceive as good." We can be wrong about what is truly good or truly best. I wouldn't necessarily disagree with the bolded part, yet I fear this framing might lead towards the another "slide into multiplicity" whereby we have many sui generis "Goods" with "moral good" constituting just one good among a plurality.

The point of a principle and measure is that it unifies a disparate multitude, resolving the problem of the "One and the Many." We can know the vast plurality of being because, even if there are infinite causes, there are a finite number of principles each realized in many times and places (Aristotle's critique of Anaxagoras at the outset of the Physics).

And I fear your following sentences confirm this suspicion. My point though is that "being good" (i.e. being truly better people, living truly better lives) is "good for us," that is, "it is actually better and more truly desirable," to be "morally good," although I would prefer to say "virtuous," instead of "morally good." Moral good is not its own sort of good here, distinct from the good of a "good car" or "good food." All related to flourishing. Rather, moral good is a more perfect manifestation of a principle analogously realized across a multitude.

That does not mean that we currently desire to be virtuous or morally good, or to act in ways that are virtuous or morally good. In the states of vice, incontinence, and continence we don't desire what is good. Rather, the point is that "if we knew the truth about what is better, we would prefer to act virtuously and to be virtuous," and "if we did not suffer from ignorance or weakness of will, we shall always choose the better over the worse." Again, Milton's Satan does not say "evil be thou evil for me."

Since you agree that it is better to be Socrates, rather than a cowardly version of Socrates, then it should make sense why it is good for Socrates to be virtuous. Socrates is free to "do the right thing," in a way the cowardly Socrates is not.

It could be the case that telling the truth in a particular case will do you no good whatsoever – it is not a good for you -- but truthtelling is still important to our community, so we recommend it nevertheless.

It seems plausible that telling the truth sometimes does no one much good. This is why I prefer the term "virtuous" to "morally good" and to focus on people and not individual acts. In The Dark Knight was Batman right to hide (to lie about) the fact that Harvey Dent degenerated into the monstrous Two Face? That seems to be what the film would lead us to believe. But rather than quibble over whether any individual deception is morally good or bad, given the vast contingencies involved, I think it's easier to say that it is better to be "prudent, loving, and charitable, etc." such that one is virtuous in how one goes about any such decisions.

"Know thyself" is, in part, an ethical command. This is why analyzing acts in abstraction is often unhelpful. Would it be better to stick up for someone who is being unfairly punished and to take the blame oneself (particularly if you are the person truly responsible)? Probably. But if you know yourself well, and you know that you're very likely to buckle under pressure and then shift the blame back onto the person who was going be unjustly punished, and you know that this in turn will make their punishment far worse, then perhaps you shouldn't do that.

More realistically, it isn't always good to over-promise, even if your promises involve doing good, if you know you won't be able to keep those promises.

Yes, the equivocation is a matter of degree. But if they meant exactly the same thing, the statement would be vacuous.

Are the theorems of geometry vacuous because they are already contained in Euclid's postulates? Are syllogisms vacuous because all conclusions are contained in the premises? Is deterministic computation vacuous because its results always follow from the inputs with a probability of 100%?

We might think "2+2" is just another way to say "4," and "1 ÷ 3" just another way to say "1/3," but "179 ÷ 3 " is "59 and 2/3rds" seems genuinely informative unless you're an arithmetic prodigy.

Plus, not all circles are viscous circles. I would say "it's good (truly better) for you to be good—to be a good person and live a good life," is circular in a sense, but the way an ascending spiral is circular. It loops back around on itself at higher levels, with greater depths beneath it, in a sort of fractal recurrence.

The point of a truly transcedent Good, Hegel's "true infinite " as set against the "bad infinite," (the latter being defined in terms of the finite, the former being truly "without limit") is that it is never fully "contained." As St. Gregory of Nyssa has it, the beatific vision is an infinite asymptotic approach to the One who is the Good.

Since I tend to agree with Hegel's case for a circular, fallibalist epistemology, I see no great difficulty in the lack of a "foundation." One cannot find such a foundation for any facts, not "I have hands," nor "the principle of non-contradiction holds." Reason, being transcedent, can always question such foundations—"the Logos is without beginning or end" because it is the ground for "beginning" and "end," "before" and "after."

As to the idea that "all fortune is good fortune," I feel like that is a separable proposition and it only makes sense in framed in the rather complex philosophy of history and Providence that comes up through Eusebius, St. Jerome, Boethius, St. Maximus, etc. and perhaps recovered to some degree by Hegel (a theology student who encountered the Patristics). It requires a corporate view of man and of man's freedom, e.g., St. Gregory of Nyssa's view of Adam as containing all men, the idea that particulars are "in" their principles (Diophantus), like the idea that all Jews , even those alive today, were present at the presentation of the Torah (Deut 29:9-14).

The point is that the identity of Lady Fortuna, properly understood, is Providence.

:up:

Right, it's worth noting that Hume's division on comes up in a particular context where renewed Euthyphro Dilemmas are leading to ideas like Divine Command Theory where "what is good," is ultimately tied to some sort of inscrutable act of will. The question, "is God's freedom limited by the fact that God can only do what is good," is incoherent on the understanding that God is Goodness itself.

I know of no similar move in the Eastern tradition or among the Islamic scholars, and the ancient Western ideas that get somewhat close are still quite different. This is where Taylor's "subtraction narratives" of secularism, where secularism is just "rational thought with superstition removed," are dangerous, because it obscures the setting in which Hume's point is makes any sense at all.

I think that, like so much of Hume's thought, the Guillotine relies on question begging. Hume is a diagnostician, seeing what follows from the assumptions and prejudices of his era. But ask most people "why is it bad for you if I burn out your eyes, or if I burn out your sons eyes," and the responses will be something like:

"If you burn out my eyes it would be incredibly painful and then I would be blind, so of course it wouldn't be good."

The response: "ah ha! Look, you're tried to justify a value statement about goodness with facts!" and the idea that what is "good" doesn't relate to these facts is prima facie ridiculous here. As JS Mill says, "one has to make some significant advances in philosophy to believe it." You only get to a position where it possible for it to be "choiceworthy" to prefer "what is truly worse," is if you have already assumed that what is "truly worse" is in some way arbitrary or inscrutable in the first place. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

Sample: A: “I don’t see what good will come out of exercising and eating a balanced diet.” B: “No, it’s healthy for you to be healthy.” A: “Oh, I see. Exercising and good nutrition will make me healthy, and being healthy is desirable and good for me.” I’m sure you can analyze this for yourself and see why it involves different uses of “healthy” to avoid vacuity.

The terms here aren't completely equivocal either though. They have an analogous relation.

I’m saying that when an individual does good things for their own sake, they are made good as a result. And the way in which they are now good is exactly the same as the way in which those good things are good. The concept of ‛good’ has remained the same; it’s the individual who has united themselves with the Good.”

But the good by which someone is a "good leader" or a "good basketball player," is not univocally the same good as that of a "good pen" or a "good knife." Just as "lentils are a healthy food" a way different from "J is healthy."

And now we return to the question of the “good” of Socrates’ execution. If what you’re saying is that Socrates has become a better person by accepting his death, we have no argument. If you’re saying that Socrates has united himself, as an individual, with something we can broadly capitalize as the Good, again we agree.

Right, but this is the whole point. As respects the human good, good is primarily said of persons. A "good life" is not atomistically divisible into a collection of "good acts" or "good moments," such that we tally up the score at the end via some sort of calculus. François Mauriac's The Viper's Tangle is an excellent example of someone becoming a "good person" only at the end of a "bad life."The relation is to the whole. Socrates is a good person who lives a good life; his death doesn't change this. We could consider Socrates claim in the Phaedo that philosophy teaches us how to die, because it teaches us not to become entrapped by goods that will inevitably be lost.

Laying all this out, I’m aware that it’s partially an appeal to something I find self-evident among English language-users, and I hardly know what more to say to justify that. I don’t mean I couldn’t be wrong, and what I’d actually like would be for you to show me some usages of “good” that contradict this in a relevant way. And mind you, I don’t mean good as in “better than” in the “lesser of two evils" sense. I mean an actual, positive "good for me." Maybe there’s some way we speak of "good for you" that I’m overlooking or failing to see clearly. But I hope this gives you a better sense of why I think the “two equivocal notions” idea is important.

You are pivoting from "'it is good to be good' is vacuous," to "executions and maiming are good." But no one claims this. Indeed, Socrates claims that it will be evil for the citizens of Athens to execute him. The reason it is not primarily bad for Socrates is because it will not rob him of being a "good person" or having lived a "good life," nor of his virtue, nor his grasp on what is truly best.

Again, the focus on the isolated act is probably unhelpful for understanding where the ancients are coming from. Consequentialism is full of strange paradoxes. Is it good to be maimed? On average, no. In some cases, it might be the best thing that ever happened to someone. We can suppose a story about a poor Persian street child, who has been neglected and is driven around by their appetites and passions to survive on the streets of Persepolis. They get caught stealing a loaf of bread and have the offending hand lopped off.

Yet we could well imagine a case where this causes some benefactor to take pity on the child, to take them in and raise them, and this results in the child living a fulfilling and successful life, becoming a virtuous person, etc.

Likewise, it's normally good to send someone to a high end school. Yet we can easily imagine a case where an otherwise successful and virtuous student has trouble adjusting to a wealthy private school, falls in with the wrong crowd, and spirals into vice and ruin.

Yet ethics is primarily about what we can choose, and what we can choose in terms of our own capacity for self-determination often relates to how we respond to fortune, or the acts of the wicked.

When people say "it is good for you to be good," in the overwhelming number of cases they are attempting to draw a contrast between apparent or lesser goods, and true and greater goods. That is, it is "better for you to be virtuous, to enjoy charity, to love, to be prudent." You could probably almost always rephrase it better as "it is better for you to be a good person then to pursue these apparent or lesser goods."

I cannot conceive of being maimed and tortured as not robbing someone of their flourishing – unless you arbitrarily make “flourishing” torture-proof, thanks to previous "patterns of behavior." It seems the very epitome of such a robbery to me. Does it make them a bad person? Of course not. Was it the lesser of two evils?

Again, this seems to be trying to make the case that it isn't evil to torture or maim people. Who is going to claim that?

The point is, as you allow, these things do not rob Origen or Maximus of their virtue, or of their having lived a good life, just as Martin Luther King's being shot did not make his life a bad one. Would it be better for MLK to have not been shot? Sure, but "getting shot" is not an ethical choice he made, it was an evil choice made by James Earl Ray.

Socrates is not saying that good men never stub their toes, or get the flu. He is focusing on what goodness is primarily said of.

This all by way of making the point that we can follow others in valuing virtue-theoretic approaches, but I don't see the virtue theorist as escaping any of the problems which deontologists or consequentialists or specifications therein deal with -- that this is something of an overpromise. The ancients are interesting because they give us a point to reflect from but they don't overcome the problem of choice -- which is to say, should I follow Christ, or should I follow Epicurus?

I'm not particularly sure what you're expecting, someone to decide for you? People refuse to accept that the Earth is round, they deny the germ theory of infectious disease, they think floride in their water is a mind control technique, they disagree about what the value of 1/0 should be, or if something can simultaneously both be and not-be in an unqualified sense. Rarely, if ever, do demonstrations in any sense "force" people to see the correctness of some view.

Is the idea that anyone who affirms a certain ethics or metaphysics shall become perfected by it if it is "the right one?" But this runs counter to the philosophy underpinning many systems of ethics. Epictetus claims most "free men" are, in truth, slaves. Plato doesn't have everyone being easily sprung from the cave. Christ says at Matthew 7:22-23:

"Not everyone who says to Me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of My Father in heaven. Many will say to Me in that day, ‘Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in Your name, cast out demons in Your name, and done many wonders in Your name?’ And then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from Me, you who practice lawlessness!’" -

How do you define good?

I don't understand how the Good would be sought for its own sake.

Aristotle's example of what is sought for its own sake is eudaimonia—roughly "happiness," "well-being," or "flourishing." This appears to be a strong candidate.

Does this imply, as many used to believe, that goodness is a kind of transcendental, independent of contexts and intersubjective agreements?

It can, but it need not. However, if the Good was properly "transcedent," then—by definition—it cannot be absent from that which it transcends (e.g. the contexts of intersubjective agreements).

Likewise, if the Good is absolute, then it is not merely "reality as set apart from appearances," but is rather inclusive of reality and appearances. Appearances are really appearances, and how a thing appears is part of the absolute context. This is why the Good cannot be a point on Plato's divided line, it relates to the whole. But appearances aren't independent of what they are appearances of, and whatever appears good must really appear good in some sense.

At any rate, it is one thing to say that the Good is filtered through or shaped by intersubjective agreements, it would be quite another to say that it is "intersubjective agreements all the way down," or not explicable in terms of anything other than such agreements. Since notions of Goodness apply seemingly everywhere, we might think it is an extremely general principle.

Aristotle, for instance, thinks happiness transcends one's own lifespan. If, for instance, one has lived a life centered around one's family, and one dies trying to save them from a flood, and yet they nonetheless end up drowning later that day, then this is not a "happy ending." "Count no man happy until he be dead," is the famous saying here (actually from Solon), but the Bible has its own version, Sirach 11:28:

Call no one happy before his death;

a man will be known through his children.

Seems to me that goodness varies greatly over time.

Does goodness change, or beliefs about what is good? Beliefs about everything vary by epoch, culture, and individual. Yet we normally don't want to say that the subjects of those beliefs change. For example, the cause of small pox didn't change when people began to believe it was caused by a virus. Rather they came to believe small pox is caused by a virus because it is so. Likewise, the age of the universe is normally not taken to change when beliefs about this fact do, and this holds even though the specific measure of time we generally use to present and understand "the age of the universe"—the year—is a social construct.

While I don't think I'm a total relativist, I don't see how we can move beyond the culturally located nature of goodness. I get that many of us believe in moral progress and argue for various positions (which implies better and worse morality) but is it any more than just pragmatically trying to usher in our preferred forms of social order?

Why prefer some forms of social order over others? Presumably because we think they are truly better. Pragmatism only makes sense if one has an aim in the first place. -

How do you define good?Here is a decent start:

Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that at which all things aim. But a certain difference is found among ends; some are activities, others are products apart from the activities that produce them. Where there are ends apart from the actions, it is the nature of the products to be better than the activities. Now, as there are many actions, arts, and sciences, their ends also are many; the end of the medical art is health, that of shipbuilding a vessel, that of strategy victory, that of economics wealth. But where such arts fall under a single capacity- as bridle-making and the other arts concerned with the equipment of horses fall under the art of riding, and this and every military action under strategy, in the same way other arts fall under yet others- in all of these the ends of the master arts are to be preferred to all the subordinate ends; for it is for the sake of the former that the latter are pursued [e.g. for the sake of the rider that we make saddles, or the golfer that we make good golf clubs]. It makes no difference whether the activities themselves are the ends of the actions, or something else apart from the activities, as in the case of the sciences just mentioned.

If, then, there is some end of the things we do, which we desire for its own sake (everything else being desired for the sake of this), and if we do not choose everything for the sake of something else (for at that rate the process would go on to infinity, so that our desire would be empty and vain), clearly this must be the good and the chief good. Will not the knowledge of it, then, have a great influence on life? Shall we not, like archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what is right? If so, we must try, in outline at least, to determine what it is, and of which of the sciences or capacities it is the object. It would seem to belong to the most authoritative art and that which is most truly the master art.

https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.1.i.html

So, one might assume that whatever the Good is, it is sought for its own sake and that it must be a principle realized unequally in a disparate multitude of particulars (e.g. saddle making, painting, argument, health, etc.). One might also assume that other things are sought in virtue of the degree to which the perfect, possess, or participate in this principle.

Plato's image is of the Good as a light by which we see. I think this works in some ways. We can imagine a very bright spotlight, too bright for us to look directly at perhaps. But between us and the light are a vast multitude of variously colored panes of glass through which the light passes, as well as different sorts of mirrors reflecting the light, and all sorts of things lit by the light, which hang from the ceiling.

Depending on how the light travels to us, how we stand and turn our heads or move about, the objects hanging from the ceiling might look very different as refracted through the intervening panes and mirrors. The objects we see are of different sorts, just as the good of a "good car" is different from the good of a "good rifle." And some panes of glass we look at the objects through might be tinted dark, such that very little light gets through, whereas others might be clearer, allowing more of the light to reach us. Some of the things we can see might be larger, as "good health" is more relevant than "a good pen." Some of the mirrors might be fun house mirrors that manage to distort the light, so that we are confused about what we see. Small things might appear large, and large things small. In some cases, we might mistake the brightness of a mirror with the source of the light itself, just as people thought the Moon was the source of its own light for millennia.

Perhaps behind all the things hanging from the ceiling there are many different lights? But I should think just one. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

But the achievement of ataraxia is what's truly eudemon, no?

Maybe for many of the Stoics, and arguably for Aristotle, but I think what ataraxia normally describes is just the lower stages of the "beatific vision." We want to ascend beyond that! To henosis and hesychasm, and beyond even that, to the ultimate goal of theosis and deification.

That's the ultimate telos of man in the Christian development of the tradition at least(and from what I understand Sufism is quite similar). As St. Athanasius' says in On the Incarnation "God became man that man might become God." Or St. Paul: "Christ is the firstborn of many brethren," partaking in the "incomparable glory."

For Boethius, the "Stoic medicine" is a numbing agent to help him get back on track for the ascent after the whole death sentence thing. Lady Philosophy likens it to bending a bent stick too far in the other direction in order to straighten it.

This is what I'm skeptical of. Not in principle, but certainly in practice. We need look no further than the success of the Catholic church to realize that the program doesn't teach us to be virtuous -- else the society would have no need for rituals of cleansing.

I feel like there is a wealth of evidence from the psychology literature to support the notion that virtue (or some instrumental approximation of it) can be taught, or that education is conducive to virtue. But, since virtue is self-determining, no education ensures virtue. Alcibiades has Socrates as a teacher and it doesn't save him from vice.

Overall though, I think the effects of mass education, as poorly as it might be implemented, are still a huge net positive. For one, it makes societies more self-determining, more able to reach collective goals. Certain desirable social systems are unworkable without most citizens having some sort of education.

But as it is it's basically set up with the belief that no one can achieve the good. What good is that good?

I'm not sure if I get what you mean here.

Really? I find this dichotomy occurring constantly in the Platonic dialogues. If these two concepts were so inseparable, why do so many of Socrates’ interlocutors dispute it? It reads to me like the debate was hot and heavy then, as it is now.

BTW, this is absolutely true, but Plato is essentially the origin point of the classical metaphysical tradition. He is staking out the ground for what would become the philosophical "tradition." The other thing is that Plato is using the dialogues to contrast bad (and poorly informed) opinions with better ones, and apparent good with what is truly good. The "agreement" MacIntyre references respects what the philosophically/theologically adept generally thought vis-a-vis what constituted the "better opinions" and "real good," not what "everyone thought was good," or what the "learned" actually managed to pursue. Italian mercenaries probably weren't reading too much of Boethius for instance, even if he was the best seller of the middle ages.

Second, I don't think anyone wants to claim that "most people" had bought into the ethics that flow from "classical metaphysics," even when it was dominant. Due to the technological, political, and economic realities of the time "most people" were illiterate serfs. So, the claim of (relative) consensus is much more about the people serving as tutors for the nobility, those in the university system, the learned, etc.

Also, contemporary scholars might balk at my mixing Plato, Boethius, Aquinas, etc. into unified position. The common thing to do in contemporary analyses of this tradition is to break up the thinkers and show how they differ. But, per this tradition itself, this would be to fall victim to the "slide into multiplicity," to focus on "the Many" rather than the unifying "One," i.e., the unifying principles that run through the whole tradition from Plato up into St. Bonaventure and Meister Eckhart. Part of the reason medievals are comfortable throwing together Plato with Pseudo-Dionysus, right next to Muslim and Jewish scholars, is because of their conviction that the core of everyone's project is the same unifying principles. As St. Augustine says "all truth is God's truth." This is the "Logos universalism" that Tilich speaks about. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

I only ask that you acknowledge the “for you” in “It will be good for you to study philosophy.” And it is a sensible and coherent thing to say. But again, consider “It will be good for you to [be good / do good things / live a good life – I’m not sure which way of filling this out you prefer].” What is being said here? That the good you do will also be good for you?

Well, on the classical view, studying philosophy is "good for you" because it makes you a good person who loves justice and acts justly. In the Republic, each of Plato's interlocutors are a stand-in for one of Plato's "types of men" (e.g. 'tyrannical man," "timocratic man," etc.). Through their interactions with Socrates, each one "moves up a step" by the end of the dialogue (Sugrue's lectures on Plato are great for capturing all these subtle dramatic elements). In the conversation with Glaucon, Plato distinguishes between those things that are good in virtue of something else, those that are sought for their own sake, and those that are both. It seems that you are afraid that anything in the "both" category is at risk of becoming either vacuous or else must actually be composed of two equivocal notions, but I don't totally understand why this is.

But yes, doing the right thing is "good for you," this is precisely Boethius point in the Consolation. It's easy to misread his "all fortune is good fortune" as the sort of metaphysical optimism that Voltaire skewers with Candide's Dr. Pangloss. It isn't though. All fortune is good fortune for the one who is beyond fortune.

The only way I can think of for “the good you do will also be good for you” to make sense with a single meaning for “good” is simply to stipulate an arbitrary meaning for “good” that excludes all our normal personal uses, and insist that, even though we don’t realize it, the virtuous person always experiences everything as “good for him.” I find this far-fetched and ad hoc.

To be honest, I am not really sure why you think "good" must become arbitrary here. Do you think it would be "truly better" for Socrates to escape his execution by fleeing or by apologetically recanting at his trial? Would it be better for Carton not to save Darnay?

The point isn't necessarily that "getting executed is good for Socrates," although Boethius will make something like this argument, because it is indeed Socrates' execution that makes his message ring so clear, and which inspires his student Plato. If it was "good for Socrates to have people take his message seriously," then it was "good for him to be executed."

But the more general point would be that it is better not to flee, or more importantly, better to be the sort of person who will not flee. No man is totally self-determining.The world has challenges. Yet it is better to seek after what is truly good and not just what appears good or what others say is good. This is the only way in which one becomes united and self-determining. This is why Socrates says that if his sons fail to love justice they will "think themselves something when they are truly nothing." They will be more "bundles of external causes," less self-determining.

What is being said here? That the good you do will also be good for you? But if, per Aristotle, the highest good is contemplation, then being tortured to death as a result of the good you do wouldn’t seem to qualify.

Perhaps here is where part of the disconnect is. Modern philosophy has a strong tendency to atomize in its analysis. So, when we talk of freedom or goodness, we often speak of "free or good acts." Both rules-based ethical reasoning and consequentialism prioritize the act.

This allows for seemingly paradoxical scenarios. For example, suppose we have a relatively unvirtuous Frenchman, a young guy who is a boaster, a drunk, an adulterer, lazy, gets into fights, and is a bad father. But, due to a pang of conscience, he hides a Jewish neighbor from the Nazis. He does the right thing here. As a result, he gets caught and sent to a concentration camp. He has a terrible time and develops bad PTSD. His wife, thinking him dead, leaves him. He becomes a full time drunk, lives a miserable life, and dies in a Marseilles gutter at 45.

Now suppose that he was young during the war and had a rough childhood but, had he not hidden his neighbor, he would have grown out of some of his bad habits. Maybe he even would have found God and reformed in a major way, becoming deeply spiritual. He would have become virtuous, had a life of contemplation, better fortune, etc. all due to doing the wrong thing. Well clearly, it cannot always be good for us to do the right thing!

But this is the problem of focusing on acts and unknowable contingencies. Aristotle claims being is "primarily said of substances," things, most appropriately beings (i.e. chiefly organisms which possess a principle of self-organization and self-determination). The case for this is that acts don't occur without things. We do not have "running" in the absence of something that runs for instance. So, while we might usefully speak of free or good acts, it is primarily people (and perhaps organizations) that are good or free. And this particularly makes sense if we think of virtue as a habit, and happiness as being defined as a "good life" not a "good state" (Aristotle, Solon, Athens' great lawgiver, and the Wisdom of Solomon all note that we shouldn't consider a man's life happy until he is dead).

So the question is not primarily: "depending on the vicissitudes of fortune, will it always be better to commit to isolated 'good acts?'" The question, at least on the classical view, is: "will it always be better for a person to be more virtuous, to be a better person, to be the sort of person who enjoys doing good?"

In our example, we might say that our Frenchman's problem is not, in the end, that he "did the right thing and suffered for it," but rather that he lacked the virtues necessary to do the right thing and flourish despite the consequences. After all, Aristotle allows that we can be merely continent, forcing ourselves to do the right thing but hating it. The real question I think though is "would we rather be a person like Gandhi, Socrates, or Boethius, and do the right thing and be happy in this choice?" That is, would we prefer:

A. Not to want to do the right thing at all (vice).

B. To want to do the right thing, but to chicken out because of the consequences (incontinence)

C. Do the right thing, but end up hating it, or having it ruin you, like our example (continence)?

D. Do the right thing and be happy about it, and have it strengthen you? (virtue)

It seems to me we want to be D and are better off if we are D, particularly if we think of these as patterns of behavior, not in terms of isolated acts. And this doesn't require the absurdity that someone like Origen or St. Maximus enjoys being maimed and tortured. Rather, the point is that even this, the height of bad fortune, doesn't rob them of their flourishing.

So, we could ask things like: "well didn't Saint Augustine need his wealth, good education, and soaring career at the imperial court to get to the place where he could give up all his wealth, his status, sex, etc.?" Probably. Nowhere does the classical tradition suggest that good things like education, a stable childhood environment, etc. aren't conducive to virtue. The whole idea of the classical education, so well defended in C.S. Lewis' The Abolition of Man, is that virtue can be taught. The point is rather that these are simply means to what is sought for its own sake.

To sum up: it's better to be the sort of person who loves justice. Continence, doing the right thing when we don't want to, is good because it leads to being a virtuous person, not because every individual continent act situated in the contingency of the world results in long term benefit (how would one even confirm or deny such a thing?) -

Why ought one do that which is good?I guess the other thing is that "doing the right thing" in contemporary ethics tends to be sensuously sterile, and this can make it seem bizarre how it could truly be "best for us."

But Plato talks about the desire to "couple" with the Good, which is apparently every bit as erotic as in the original Greek. We get this vision in the Symposium:

And the true order of going, or being led by another, to the things of love, is to begin from the beauties of earth and mount upwards for the sake of that other beauty, using these as steps only, and from one going on to two, and from two to all fair forms, and from fair forms to fair practices, and from fair practices to fair notions, until from fair notions he arrives at the notion of absolute beauty, and at last knows what the essence of beauty is.

Or St. Augustine in the Confessions:

Late have I loved you, beauty so old and so new: late have I loved you. And see, you were within and I was in the external world and sought you there, and in my unlovely state I plunged into those lovely created things which you made. You were with me, and I was not with you. The lovely things kept me far from you, though if they did not have their existence in you, they had no existence at all. You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew in my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours. -

Why ought one do that which is good?

It's possible my explanation is bad. I don't think these are two different uses at all, and I don't think Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, St. Augustine, Boethius, etc. intend them as such.

When people say, "it will be good for you to study philosophy," "it will be good for you to start exercising," or "it's good for you to learn to appreciate Homer, Hesiod, and Horace," they certainly don't mean "you will enjoy those things." People often tell people that "x will be good for them," precisely as motivation for them to do things they do not want to do, even when the primary proximate beneficiary of these acts is the person doing them (although it isn't only for the good of the person undertaking these challenges; the champions of the liberal arts tend to argue that all of society benefits from the student's efforts).

Perhaps pornography is a good example here. When people say, "you shouldn't consume pornography, it will mess with your ability to have healthy relationships," they are generally speaking about both one's ability to to enjoy a healthy relationship, but often even moreso one's ability to be a good partner for someone else. Yet what is good for the whole is good for the person who is part of the whole, and someone's inability to be a good "part" is "bad for them" for the same reasons that it is bad "for everyone else." For Aristotle, this analysis tends to stop at the limits of the polis (although not exclusively), whereas for someone like St. Augustine it extends to the entire world, but it's the same idea.

Second, consider Book X of the Ethics where Aristotle identifies the life of contemplation as the highest good, the most divine. Plenty of thinkers agree with Aristotle here (even seemingly some in Eastern traditions). Suppose he is right. Well, in this case, what is most "good for you," is to have your wonder (the first principle of philosophy and science) satisfied. Yet, on the classical view, this is simply impossible for the person who lacks virtue. Indeed, for Plato it seems that it is impossible to truly know the Good and to act wickedly (e.g. the Parmenides). Likewise, the beatific vision, St. Augustine's ascent with St. Monica in Book IX of the Confessions, or St. Bonaventure's ascent in The Mind's Journey to God cannot be accomplished by the wicked. One cannot fully achieve these while giving in to lusts (or perhaps even still being tempted by them), coveting, etc.

It's a contradiction in terms to say that one could "do wrong" while having the best for oneself. Consider St. Augustine's argument that the soul in Heaven, having been perfected, has become so free that it is incapable of sin (for the same reason that the person most free to run never trips and falls over). This isn't just a Christian idea though, Porphyry's Pythagoras and Philostratus' Apollonius of Tyana are both saints, and we might add Plato's Socrates here.* They have what is "best for them," and in having this they are going to be doing "the right thing." Likewise, St. Athanasius' St. Anthony has what is truly "best for him," Christ, and it is by/through his possession of this that he also does what is "right." They're the same thing at the limit.

So, perhaps I am explaining it poorly, or perhaps it is just hard to not read the equivocal division of modern ethics back into the earlier ethics (MacIntyre's point).

The reason I find MacIntyre's thesis plausible is because I certainly had this difficulty with ancient thought early on. But, perhaps my own problem was approaching it too hubristically, because, honestly, my original thoughts were that Hume's guillotine, the old "is-ought" chasm simply hadn't occured to prior thinkers precisely because religion and tradition were blinding them to it. I don't think that now though, I think Hume's guillotine simply makes no sense with how Plato and Aristotle see the Good or virtue.

I think history had to pull apart the concepts of "doing right," and this being "what is best to do 'for you.'" And ultimately, I think this goes back into the birth of nominalism, the univocity of being, and the way in which "human virtue," as classically conceived, is often (perhaps not always) problematic for a theology of "faith alone" or "total depravity." You need some changes before Luther can tell Erasmus:

"If it is difficult to believe in God’s mercy and goodness when He damns those who do not deserve it, we must recall that if God’s justice could be recognized as just by human comprehension, it would not be divine."

Here is a great example of the equivocity that separates the unknowable right, "God's Good," from what is or seems "good for us," human good. And of course I mention Calvin and Luther because they are the big names, but this is certainly a shift in Catholic theology too (it starts there in late-medieval nominalism)—some "Baroque Thomism" might be called "more Calvinist than Calvin."

* I really don't think we're supposed to pity Socrates as "receiving something that is 'bad for him.'" He explicitly tells us not to think this way. It's more like Sydney Carton's execution at the end of "A Tale of Two Cities:" "It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever known." I don't think Carton would think it is better "for him" to have not gone through with his plan to die in Darnay's stead. -

Is Philosophy the "Highest" Discourse?I forgot if I shared this quote in this thread:

“For just as men of strong intellect are by nature rulers and masters of others, while those robust in body and weak in mind are by nature subjects . . . so the science that is most intellectual should be naturally the ruler of the others: and this is the science that treats of the most intelligible beings."

St. Thomas - Introduction to the Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics

Or "metaphysics is naturally the queen of the sciences."

Reminds me of a saying of my grandfather's. Whenever he needed help lifting something heavy he used to call out that he needed "somebody with a strong back and a weak mind," to come help him out. He remained full of Depression-era Brooklyn neologisms until his death in the 2010s :rofl: . -

Ukraine Crisis

Would he, after all what he has said, then truly ramp up the support of Ukraine to pressure Putin?

Potentially, yes. Trump thinks about things very transactionally. He wants to "win" any deal.

But Putin is sort of stuck with maximalist aims, which is why Russians are forced to do things like carry out frontal assaults in civilian cars and golf cart style ATVs. What is Putin going to do, declare "victory" while leaving the "Nazi regime" in power in Kyiv with explicit US security guarantees that are for all intents and purposes going to have the same effect as being in NATO, while having triggered NATO expansion to the north and having his war result in 700,000+ killed or wounded and the destruction of most of Russia's military hardware and major economic issues, all to annex some areas in the Donbas (not even the whole Donbas), which Russia already defacto controlled in 2022, plus Mariupol and some sparsely populated areas in the south?

This was what was worth all the deaths, Europe abandoning Russian energy exports, spending through their reserves, and a coup that saw Putin fleeing the capital and warning the nation about civil war on TV? And this will happen in the context of Assad's forces routing in Syria and a protest movement that looks a lot like Euromaidan sweeping Georgia and all the post Soviet states seemingly abandoning Russia for the West or China.

I can certainly see Putin being forced to overreach and this triggering a stronger response. -

Why ought one do that which is good?