Comments

-

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

If the letter is legitimate, why do you think Plato refrains from saying anything like: "I maintain that these things are unknowable, and I myself do not pretend to know them," etc.? Why does he instead talk about how the nature of knowledge vis-á-vis intelligible form is something that cannot be shared in writing rather just coming out and saying "I can't write about what I don't know about?" And then why would he imply that much conversation and a shared life can allow people to share this sort of knowledge if he himself has never experienced anything of the sort?

I find it hard to see how the skeptical Plato survives if Plato wrote the letter. At any rate, I think you are confusing "myths and images" as a vehicle for/aid to attaining knowledge with all knowledge being of myths and images alone.

:up:

Perl's take is in line with Robert Wallace, D.C. Schindler, and a number of other people I like on Plato. It seems to me that people who tend to think of the forms as existing in a magical "spirit realm" are generally hostile to Plato. I am not sure if it is their bad take on Plato that makes them hostile, or if they have a bad take because they only look at the surface level images because they are hostile to his way of thinking. It is probably a mix of both. More skeptical versions of Plato on the other hand seem more born of literalism, and in some cases a lack of imagination. -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

But eidos isn't invoked as an expedient for justifying a political system. Quite the opposite, Socrates only looks at justice within the context of a city to help pull out the nature of justice vis-á-vis the individual, and the philosopher king is analogous to the rule of the rational part of the soul. The exposition begins as a response to Glaucon's challenge re the "good in itself," not as a means of advancing a political position.

Eidos is also key to the explanation in Letter VII of why metaphysics cannot be written about in the way that Dionysius of Syracuse is attempting. In context, Plato is clearly not making a blanket pronouncement against anything that might be considered a "doctrine." You can hardly come away from his corpus with the idea that he thinks, "well, being led by the pleasures of the flesh and ruled over instinct is all well and good. After all, we cannot know the Good, so we cannot really say that the rational part of the soul has greater authority." He is instead referring to the core of his metaphysics, which the following paragraphs reference directly in explaining why he cannot produce a dissertation on such things. Nonetheless, such things may indeed be shared "after much converse about the matter itself and a life lived together," when "suddenly a light, as it were, is kindled in one soul by a flame that leaps to it from another, and thereafter sustains itself."

Eidos shows up throughout the dialogues, in the Euthyphro, the Meno, Greater Hippias, Phaedo, etc. and relates to the core issue brought up by Parmenides re the Many and the One/the intelligibility of being. E.g., "Are not those who are just, just by justice? … Therefore this, justice, is something [ἔστι τι τοῦτο,

ἡ δικαιοσύνη]? … Then those who are wise are wise by wisdom and all good things are good by the good … And these are somethings [οὖσί γέ τισι τούτοις]? For indeed it can’t be that they are not … Then are not all beautiful things beautiful by the beautiful? … And this is something [ὄντι γέ τινι τούτῳ]” (Gr. Hip. 287c1–d2)." It is not something invoked as a political expedient.

Anyhow, to quote Gerald Press: “We can surely say that if Plato did not intend for his readers to attribute to him belief in the truth of these and many other propositions [e.g., that pleasure is not the good or that forms are objects of knowledge] then he failed miserably… The anti mouthpiece camp must hold that the history of Platonism rests upon a colossal mistake … If Plato intended to promulgate ἀπορία or suspension of belief based upon balanced opposite assertions, he was a spectacular failure." We can add here that this view also entails that Aristotle, Plato's prize pupil who studied closely with the man for two decades, would then also have completely misunderstood him. -

Some Thoughts on Human Existence

The question of how life "does not grow old," in perfection is an interesting one. Consider the vision towards the climax of Dante's Divine Comedy:

That sacred army, that Christ espoused with his blood, displayed itself in the form of a white rose, but the Angel other, that sees and sings the glory, of him who inspires it with love, as it flies, and sings the excellence that has made it as it is, descended continually into the great flower, lovely with so many petals, and climbed again to where its love lives ever, like a swarm of bees, that now plunges into the flowers, and now returns, to where their labour is turned to sweetness.

Their faces were all of living flame, their wings of gold, and the rest of them so white that snow never reached that limit. When they dropped into the flower, they offered, to tier on tier, the peace and ardour that they acquired with beating wings: and the presence of such a vast flying swarm between the flower and what was beyond it, did not dilute the vision or the splendour: because the Divine Light so penetrates the Universe, to the measure of its Value, that nothing has the power to prevent it. This kingdom, safe and happy, crowded with ancient peoples and the new, had sight and Love all turned towards one point.

There is movement but it is cyclical, oriented without reserve or change towards the One. -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

There is, however, a great deal in the dialogues that call the Forms into question.

Yes, a great deal of effort is expended on trying to develop the idea and avoid the problems of collapsing into the silent unity of Parmenides or the universal inconstancy of Heraclitus.

The idea found in the Republic of eternal, fixed, transcendent truths known only to the philosophers is a useful political fiction. This "core doctrine" is a myth, a noble lie.

I don't know how you explain Plato's later, considerable efforts to figure out how to deal with the forms, universals and predicates in the Sophist/Statesman if the Forms are just a political myth (same with the troubleshooting in the Parmenides). The invocation of the Forms in the Phaedo also has a different usage. Plato uses myths often, but he doesn't bother returning to them over and over throughout his life to try to iron them out when they are just meant to be edifying alternatives for those who have failed to grasp the main thrust of his lesson.

Letter VII is specifically attempting to skewer Dionysius of Syracuse's pretenses to be a philosopher. One of the reasons to think it is authentic is that it jives very well with the Republic re the limitations of language and Plato's ecstatic view of knowledge. The letter is referring to the idea of intelligible forms in it's very explanation of the limits of language, so I'm finding it hard to see how one gets a reading out of this that would reduce the forms to "political myth" of some sort.

For everything that exists there are three instruments by which the knowledge of it is necessarily imparted; fourth, there is the knowledge itself, and, as fifth, we must count the thing itself which is known and truly exists. The first is the name, the, second the definition, the third. the image, and the fourth the knowledge. If you wish to learn what I mean, take these in the case of one instance, and so understand them in the case of all. A circle is a thing spoken of, and its name is that very word which we have just uttered. The second thing belonging to it is its definition, made up names and verbal forms. For that which has the name "round," "annular," or, "circle," might be defined as that which has the distance from its circumference to its centre everywhere equal. Third, comes that which is drawn and rubbed out again, or turned on a lathe and broken up-none of which things can happen to the circle itself-to which the other things, mentioned have reference; for it is something of a different order from them. Fourth, comes knowledge, intelligence and right opinion about these things. Under this one head we must group everything which has its existence, not in words nor in bodily shapes, but in souls-from which it is dear that it is something different from the nature of the circle itself and from the three things mentioned before. Of these things intelligence comes closest in kinship and likeness to the fifth, and the others are farther distant.

The same applies to straight as well as to circular form, to colours, to the good, the, beautiful, the just, to all bodies whether manufactured or coming into being in the course of nature, to fire, water, and all such things, to every living being, to character in souls, and to all things done and suffered. For in the case of all these, no one, if he has not some how or other got hold of the four things first mentioned, can ever be completely a partaker of knowledge of the fifth. Further, on account of the weakness of language, these (i.e., the four) attempt to show what each thing is like, not less than what each thing is. For this reason no man of intelligence will venture to express his philosophical views in language, especially not in language that is unchangeable, which is true of that which is set down in written characters.

Again you must learn the point which comes next. Every circle, of those which are by the act of man drawn or even turned on a lathe, is full of that which is opposite to the fifth thing. For everywhere it has contact with the straight. But the circle itself, we say, has nothing in either smaller or greater, of that which is its opposite. We say also that the name is not a thing of permanence for any of them, and that nothing prevents the things now called round from being called straight, and the straight things round; for those who make changes and call things by opposite names, nothing will be less permanent (than a name). Again with regard to the definition, if it is made up of names and verbal forms, the same remark holds that there is no sufficiently durable permanence in it. And there is no end to the instances of the ambiguity from which each of the four suffers; but the greatest of them is that which we mentioned a little earlier, that, whereas there are two things, that which has real being, and that which is only a quality, when the soul is seeking to know, not the quality, but the essence, each of the four, presenting to the soul by word and in act that which it is not seeking (i.e., the quality), a thing open to refutation by the senses, being merely the thing presented to the soul in each particular case whether by statement or the act of showing, fills, one may say, every man with puzzlement and perplexity.

Intelligible form here seems absolutely necessary for understanding why Plato thinks there are such limits on the type of work Dionysius is pretending to in the first place. If the fifth thing is just a pragmatic creation of words, Plato would seem to be guilty of the worst sort of sophistry here.

If you go a little further on your previous quote, it is clear that Plato is talking about the inadequacy of treaties, not "unknowability."

There neither is nor ever will be a treatise of mine on the subject. For it does not admit of exposition like other branches of knowledge; but after much converse about the matter itself and a life lived together, suddenly a light, as it were, is kindled in one soul by a flame that leaps to it from another, and thereafter sustains itself.

Note, that this also denotes an ability to share this insight, just not in a direct way.

Aside from that, I also have no idea how there could be a reading of Aristotle where he is skeptical of edios. -

"Aristotle and Other Platonists:" A Review of the work of Lloyd Gerson

Eric Perl's short little gem "Thinking Being: Introduction to Metaphysics in the Classical Tradition," makes a similar argument, but applies it more broadly to the entire classical tradition. Per Perl, major elements are contiguous between Parmenides and Plato, and on to Aristotle, and then into Plotinus and St. Aquinas—with the main thread being Parmenides' "it is the same thing that can be thought and can be.”

Perl specifically argues against the "two worlds," view of Plato, which I agree is a pretty bad reading, and one which also only becomes a thing in the modern period. Interestingly, he points to Ockham and Scotus as the end of the classical metaphysical tradition and the birth of "subject/object" thinking and "problems of knowledge" rather than more modern figures like Locke or Kant. A particularly keen observation of his is how closely ideas in phenomenology, namely "giveness" and "intentionally" hew to the classical tradition, such that Husserl's project in some ways starts to look more like a recovery of lost concepts (Robert Sokolowski, who he cites, does a lot of work in the relationship between classical philosophy and phenomenology too).

On this view, Aristotle is a Platonist offering corrections and St. Aquinas isn't really straying too far from the Neoplatonism of his contemporaries. I do think this gets something important right. Far too often, we seem to read the modern rationalist vs empiricist debate back into Plato and Aristotle, which misses their deep connections. That or they just become skeptics, trapped in the modern box of subject/object, which is an even grosser misreading, particularly of Aristotle. -

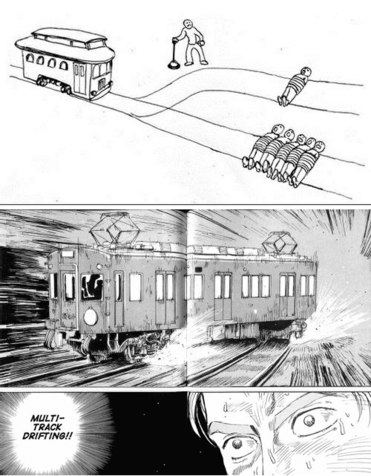

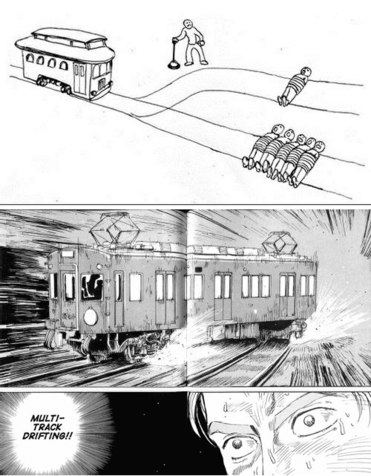

How would you respond to the trolley problem?It's not clear which answer is right, and yet it is clear that this answer is wrong:

...so it does seem like we can make some progress in our moral reasoning. :grin: -

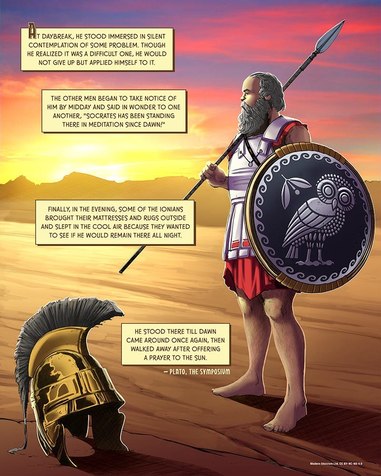

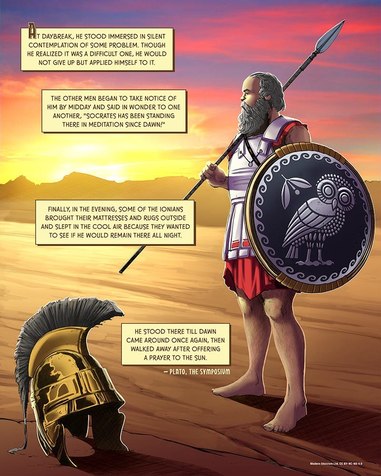

The philosopher and the person?

It was a norm that philosophers should be exceptional people who "lived out their ideals" up to the modern period. Many seemed to do this quite well, although it's not always clear how far hagiography departs from reality here. Appolonius of Tyana or Pythagoras would be key examples outside of Socrates in the Pagan tradition, and then there is Origen, St. Anthony the Great, Evargrius Pontus St. Maximus the Confessor, etc. in later antiquity. With the Medievals, there is some overlap between the saints and major thinkers, e.g. Bonaventure, Bernard of Clairvaux, Hildegard, and this strand continues into the modern period to some degree with John of the Cross, etc. Ferdinand Ulrich is still alive but retired into contemplation decades ago. Pope/St. John Paul II might be another example, as he had both a very active life and serious philosophical chops before his big promotion ate into his time. You might throw in the transcendentalists in here as more modern examples outside the Catholic tradition.

Departing with wealth and status were the common mark of a philosopher into the later middle ages.

Also relevant:

-

Wittgenstein the SocraticAnyhow, here is an interesting contrast of the two that brings up Wittgenstein's interest in Schopenhauer as well. It mostly focuses on the Tractatus though.

https://ibb.co/ZWBMH8V -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.

Lots of philosophy involves this "looking where the light is best" (or "hammer entails nail") sort of behavior, or solutions in search of problems.

The sciences too. The whole hot debate in evolutionary theory today, the focus on genes to the exclusion of all else, seems to be somewhat a case where people would like to focus "just on genes," precisely because they are easy to measure. On the face of it though, obviously developmental biology and behavior affect selection.

Likewise, regardless of the merits of the computational theory of mind, it seems less and less plausible that brains' functioning can be explained just in terms of neurons firing or not firing. There is a whole lot more complexity there, yet you see the same focus on "what is easy to model and frame."

But, as good as this sort of insight can be:

A man will be imprisoned in a room with a door that's unlocked and opens inwards; as long as it does not occur to him to pull rather than push.

I think complaints about Wittgenstein's descendents often tend to center on this sort of thinking itself becoming totalizing. That is, everything becomes a pseudo problem, or in need of some sort of dissolution. But, taken far enough, this just falls back into the same sort of mistake. Something akin to "always focusing on how the door might already be unlocked instead of looking for keys, because it is assumed keys are unnecessary."

I don't really see this in Wittgenstein, although I can see an argument that he distances philosophy too much from human life as a whole. I think it is actually something he warns against, which makes the evolution of his thought in other hands pretty ironic.

Maybe here is where the lack of attention to history comes back to bite him. The article I posted early goes into how similar St. Augustine's ideas on language are to Wittgenstein's in many respects. But Wittgenstein himself only uses Augustine to put forth a very simplistic image of language (and I don't think he is being unfair to Augustine here, he is just not using very much of him). So, his ideas then aren't connected to past thought in a way they might have been.

Why does this matter? Well, in terms of dissolution and the hunt for "pseudo problems" becoming totalizing itself, I think it would have been helpful for Wittgenstein's descendents to see where some predecessors had quite similar thoughts, and how they had already tied into the history of philosophy and various problems. That way, you don't get a totalizing vision of "wiping the slate," entirely clean of the sort that makes the world look entirely like nails for the hammer of dissolution. Maybe. I'm not sure about that lol. I tend to find the historical comparisons useful though. -

Wittgenstein the Socratic

What could the value of metaphysical speculation consist in if not to show us that metaphysics is undecidable, and not a matter of reaching some theorem which is guaranteed to be correct by rigorously following the rules?

I think this would be radically underselling it. Consider the image of the soul—the charioteer of reason training the two horses (the appetites and passions)—in the Phaedrus. It is the image of the divine that gives the charioteer the wherewithall to break the black horse of the appetites and train both horses so that the soul functions as a unified entity, rather then there being a "civil war within the soul," (the phrasing of the Republic). So what is at stake is ultimately the freedom of the human person, since it is reason, and its ecstatic nature, that allows us to go beyond current beliefs and desires in search of what is "truly good," not just what is said to be good or appears to be good. As Socrates says at like 510D (IIRC), everyone wants what is truly good and despises opinion in these matters (reality vs appearance).

So it's absolutely true that we don't know this sort of thing the way we know "the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776," and we can't learn it in the same way, e.g. simply reading it somewhere. But it's not just nescience or awareness of nescience that is at stake. The whole person is ultimately transformed, reason, the most divine part of the soul (e.g. the Timaeus, the "golden thread" of the Laws) reaching down and coloring the lower parts.

This is why Plato also has Socrates speak of erotic desire for the Good (the desire to "couple" with it) and spirited love for it. It's a full reorientation of all parts of the person, which is ultimately what allows us to be self-governing and self-determing, and thus ultimately (more) fully real as ourselves. For a counter example, a rock is "less real as itself," because it is essentially just a bundle of external causes, not self-generating in any way. Plato doesn't think rocks are unreal, something along the lines of Shankara, but he does have a conception of vertical reality. The orientation towards the Good is what makes us more real as ourselves, and so this is why there is good reason for us to think it is as at least as "real" as us when we are actualized.

Also to consider here is the image of Socrates as a midwife and the idea of "giving birth in beauty," in the Symposium and the generosity of the creator in the Timaeus. Giving birth in beauty, an attitude of love, is also a key element of the perfection of freedom, and thus full reality. The ecstasis of knowing, and the identity of the self with the other in love, has a transcedent role in bringing a person beyond what they are, which is ultimately the nature of freedom in the classical tradition (i.e., the ability to do the good, rather than the potential to "do anything," act versus potency).

So, while I agree we are never free from hypothesis as long as we are in discursive mode, I think we can be free in non-discursive modes. This freedom may not be of much use for discursive philosophy, but it certainly has its role in the arts and in self-cultivation.

:up:

Letter VII might be the most clear on this. The type of knowing associated with language and demonstration is not, ultimately, the sort of union with what is known that is needed for that which is "good in itself," since discursive reasoning always involves the relative and relational. Aristotle (Metaphysics X IIRC) makes a somewhat similar distinction between two types of knowledge. First, there is the sort of propositional knowledge that combines, divided, and concatenates, which has falsity as its opposite. Then there is awareness of undivided wholes, which can be more or less full. The opposite of this second sort of knowing is ignorance, not falsity. There is a key distinction between Plato and Aristotle though in that Plato often talks about the knower going outside of himself in knowing, whereas Aristotle talks about the mind becoming like things known, i.e. more external vs internal language. -

Wittgenstein the Socratic

I guess it depends on what you mean by "zeteic skeptic." Plato seems to allow a priority to dialogue—as opposed to speeches—even as he suggests there are strong limits on what words can reach (Republic, Letter VII). A big theme in the Protagoras is that the Sophists keep wanting to leap into long speeches, while Socrates keeps trying to pull them into a "back and forth" conversation (i.e., a certain form of argumentation). This is still argument, but it isn't a type of argument that is passively received. This difference—the involvement of the other party—is key, since the "whole person" must be "turned" towards the Good to know it. We might also consider the explicit warning against losing faith in all arguments just because one has discovered that a favored argument turns out to be bad, presented during the interlude on misology in the Phaedo.

Plato seems to embrace a certain sorts of theorizing, e.g. the discussion of normative measure in the Statesman and Protagoras, just as he seems confident is a certain sorts of knowledge possessed by people, namely techne (which ties in with normative measure).

But there are limits on what can be said with words, because words always deal with the relative, and this is where I see the zeteic skeptic label being particularly apt. In particular, there is the critique of teaching as somehow being a simple "putting of ideas into a person," in the Republic. When Socrates tells Glaucon that he has no knowledge of the Good, this seems to both aim at and have the effect of drawing Glaucon on in search of this alluring knowledge. After this, Plato presents his three "images," the Good as the sun, the Divided Line, and the Cave. These images go beyond rhetoric, into the realm of analogy and metaphor, but they are still painted using language.

Notably, in each description something has to come from outside the image to explain the Good. For example, the Good cannot be on the divided line because this would make it just one point among many, and thus neither absolute nor transcedent. Rather, the Good lies off the line because the Absolute must contain both reality and appearances. Likewise, the philosopher must descend back into the cave to gather up the whole, rather than being satisfied with a part.

In the cave image it is Socrates himself, a reference to the historical Socrates, who "breaks in" to the image from without, transcending its limits. I have seen a few writers suggest that this moment is Plato's answer to Glaucon's pivotal question: "why would we ever prefer to be the man who is just, but who is thought unjust and punished by others, rather than the man who is unjust but who is thought just and rewarded by others?" Plato cannot answer this question with mere words, which are relational and thus always point to relative goods; he answers with a deed, the moral life and death of Socrates.

At the heart of this question is the distinction between things that are good only relative to something else, things that are good in themselves, and things that are both relatively good and good in themselves (a distinction that collapses into a binary in Aristotle, but here we can see a mirror of the appearances/reality/Absolute distinction).

Yet I think Plato thinks words, and more importantly philosophy as a whole, can do a lot for us. In the Republic, each of Socrates' main interlocutors takes on the characteristics of one of Socrates' political analogies for types of men (e.g., the timocratic man, the tyrannical man, etc.). By the end of the dialogue, each has an insight whereby they move up one level, ascending the steps towards philosophical man. Plato then, sees philosophy as a transformational process. Where his skepticism is most obvious is vis-á-vis the rhetoric and demonstrations of the Sophists. If the "whole person," is not changed, we can always reject an argument. Likewise, as we see in the Gorgias, Protagoras, Theatetus, etc., words can be twisted any way their speaker wants, resulting in dismal products, like the first speech of the Phaedrus. The image of the value of what Plato is doing then seems quite a bit different than Wittgenstein's "getting the fly out of the fly bottle."

How does this match up to Wittgenstein? It seems to me like Wittgenstein thinks that philosophy can do a lot less for us. Both philosophers see limits on what can be done with language, but it seems to me that Wittgenstein (particularly the early Wittgenstein) sees far more constraint here. Particularly, Wittgenstein's view on religious speech doesn't seem to allow for the truly transcedent role of the Good vis-á-vis human freedom and actualization that is staked out in Plato, or the Good's role vis-á-vis the Absolute.

I think Wittgenstein's image of language games as being relatively discrete (e.g. the theory of religious speech) seems to potentially be what Plato is warning against is his concerns over misology (depending on how Wittgenstein is read). Reason ultimately relates to the whole for Plato. Sophistry becomes toxic because it takes reason as being fractured—here it applies, here it is bent to my will, here it is just formalities. But for some of the intellectual descendents of Wittgenstein this is precisely what they take Wittgenstein to be positively arguing for in parts of PI (e.g. the part about the king who thinks the world began when he was born), i.e., different games cannot speak to one another because reason does not transcend them.

Of course, Wittgenstein is read many different ways, and sometimes Plato is deflated into an out and out skeptic on everything, so they can variously be quite far apart or quite close together. I would tend to think them quite far apart on several readings though. If Wittgenstein's king is taken to represent that truth is dependent on presuppositions that cannot be reached by reason, or if his ideas on language are taken more generally to say that games are what we know rather than being an (imperfect) tool vis-á-vis knowledge, I'd say the two are skeptical about quite different things.

As to midwifery, I see similarities in approach in some ways. But the idea of "giving birth in beauty," so potent in Plato, doesn't seem to be in Wittgenstein the same way (this would be a good or bad thing depending on who you ask). -

Currently ReadingHans Urs von Balthasar's "Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Saint Maximus the Confessor." Aside from being a rare deep dive into IMO one of the most underrated thinkers of late antiquity/the "Dark Age," is is also one of the most exquisite works on Neoplatonism in general that I've ever seen and is expertly crafted despite very challenging source material. The part on conceptions of mathematics in Christian Neoplatonism is especially good and you can see the foreshadowing of Eriugena and Hegel.

It also has some good coverage of John of Sythopolis (a major early commentator on St. Denis) and St. Denis himself.

Here are some of the pages on number if anyone is interested.

https://ibb.co/q11kHL1

https://ibb.co/4ZDhbyK

https://ibb.co/Hgcb9xh

https://ibb.co/XjYYFbk

https://ibb.co/SnZyd5P

https://ibb.co/MgnKntN

Maximus would famously have his tongue cut out and his writing hand lopped off for refusing to recant on his core ideas, so we're lucky that so much of his writing has survived for us. I believe he is the last thinker of the East to be considered a "Doctor of the Church," by the Latin Church. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

I was referring to the reduction of one science to another, and all of them eventually to physics.

Yup, me too. Conciousness comes in because supposedly it can be reduced to physics.

Now let's take a step back. Why did it occur to you to raise a counterexample to my observation? There wasn't much riding on my being right. I hadn't used the claim as a lemma in an argument. If you show that I was wrong, how do you expect that to affect whatever position you think I hold?

Well, from my view, what people think about the world shapes culture and how they behave. This makes it important. You can't divorce what people think about justice, beauty, and truth from philosophy, and these play a major role in history. Looking back historically, you see philosophical thought playing a major role in politics (and thus everyday life) in the Reformation, Enlightenment, etc. I don't think we have some how "moved beyond" this influence. The anti-metaphysical movement has just obscured this influence by redefining what philosophy is and trying to deny it a determinant role in culture or in the arch authority of "science" (which of course, is its own sort of "philosophy influencing culture").

At least in my experience, "the world is just atoms in the void, atoms don't have purposes, thus either there is no such thing as good and bad or else good and bad is something we 'create'" is a series of statements I see in all sorts of conversations: discussions of politics, discussions of fiction or movies, discussions of romantic relationships, etc. But this is clearly a view that is based on a sort of corpuscular metaphysics, even if it isn't examined that way and is simply taken to be "the way science says the world is."

And similar sorts of things pop up elsewhere. The idea that the world is a "simulation," the idea that reason is fractured and can't apply to certain areas of human life (ethics, religion, etc.). These seem pretty central to human life and identity. To say that, "people don't question if God exists in the way sets do," is evidence that they aren't interested in philosophy just seems to me to be too narrow of a definition of philosophy.

I think there is a lot of philosophy on the non-fiction best sellers list. It just doesn't tend to be written by academic philosophers. Tegmark's "Our Mathematical Universe," Pinker's "The Blank Slate," Scharf's "the Ascent of Information," Eddington's "The Rigor of Angels," Eckhart Tolle, etc. all have plenty of philosophy in them. In general, I think most good theoretical work in the sciences (and a lot of popular science) tends to involve philosophy. Not without reason is Einstein also called "the most important philosopher of physics of the 20th century." Likewise, folks like Rawls and Nozik get assigned to our future leaders in public policy programs, while undergrads in biology get asked questions in the philosophy of that field like: "what is life and are viruses alive?" or "are species real?"

I tend to think the philosophy that permeates the popular imagination often has pretty major consequences, even if it's hard to see in the moment, simply because this seems ostentatiously true vis-á-vis prior eras (now that it's all in the rearview mirror.) This is part of why I am not a fan of the anti-metaphysical movement.

Anyhow, moving back a bit:

Caveat number 2: it's widely understood that even statements of fact -- observations and such -- in the context of science are relative to a given theoretical framework. There's no pure non-theory-laden observation to be had, and no one pretends otherwise; rather, it's the theory that enables the observations to be made at all. (More Kant, etc. And absolutely every philosopher of science.)

Yup, but the conclusions which are drawn from this vary quite a bit. We are drawn to ask: "where do theories come from?" That they have cultural, linguistic, and historical determinants is obvious, but there is a weird tendency to move from this insight to the idea that this makes them in some way arbitrary, and thus disconnected from truth. "X is socially and historically determined, thus X cannot tell us about the way the world really is." Well, shouldn't history and culture themselves be determined by how the world is? The ghost of the positivist ideal of "objectivity as truth," seems to be lurking behind this, as well as the assumption that ideas, theories, language, etc. are all what we know instead of how we know.

Hegel's stance, that knowledge must come to involve an understanding of how it comes into being, seems like the more warranted response here. This will be circular, but all epistemology is circular if "the truth is the whole." Funny enough, there is an overlap between Popper's evolutionary account of science and Hegel's conception of all culture advancing due to internal contradictions.

To the extent that theory ladeness is used to support more pernicious forms of relativism, I tend to see the modern focus on potency over act at work. We can imagine theories being constructed and differing in seemingly infinite ways, thus we have a problem. But the reality is that we don't have infinite theories, we tend to have just a few competing ones, and they don't evolve arbitrarily.

Essentially, I think the historicity of knowledge is not a barrier to truth at all, but rather an aid to it. Culture, like words and ideas, is something we use to get to/through the world, not merely the object of our knowledge. All effects are signs of their cause, so culture just points back to that from which it emerges. Like you said, pluralism doesn't entail that everyone is right. I also don't think it entails a problem for truth unless truth itself is denied (the pernicious sort of pluralism/relativism). Gallagher puts it well:

existence for himself is integral to the cognitive grasp of the transcendent dimension of reality. [/quote]Only the abstract is non-historical. Philosophy is, or should be, an effort to think the concrete. That is why it cannot attempt to surmount the conditions of temporality by seeking out categories which seem to be exempt from history, as do mathematics and logic. It is true that any mind at any socio-historical perspective would have to agree on the validity of an inference like: If A, then B; but A; then B. But such truths are purely formal and do not tell anything about the character of existence. If metaphysics views its categories as intelligible in the same manner, it has really taken refuge in formalism and forsworn the concrete. That is why a metaphysics which conceives itself in this way has such a hollow ring to it...

...Let us now consider the second aspect of the sociology of knowledge, its positive contribution. For the impression must not be left that the social and historical dimensions of knowledge are simply a difficulty to be somehow "handled" by one who wants to continue to maintain the objective value of our knowledge. This would be to miss the very real contribution made by the modem historical mode of thought to our appreciation of what objectivity is. Here we may advert to the remarks made in connection with Kant's view that we can only be properly said to know things and that only phenomenal consciousness (a combination of formal category and sense intuition) apprehends things. To this we may add, with Dewey and the pragmatists, that action is also involved in the conception of a "thing."24

Now with this in mind we may confer a very positive cognitional relevance on the social and historical dimensions of human existence. For if metaphysical categories like "being," "soul," "God," "immortality," "freedom," "love," "person," and so forth are to afford us the same assurance as phenomenal knowledge, they must be filled in with some kind of content-they must begin to bear upon something approximating a "thing." Now obviously this content cannot come from the side of sense intuition as such, which cannot exhibit these notions. It might come, how-ever, from action of a superior kind. And here is where the social and historical dimensions become extremely relevant. For it is through his higher activity as a social and historical being that man gives a visible manifestation to the meaning creatively apprehended in these philosophical concepts. His grasp of himself as a trans-phenomenal being is weakened and rendered cognitionally unstable unless he can read it back out of his existence. Therefore, the historical process by which he creates an authentic human existence for himself is integral to the cognitive grasp of the transcendent dimension of real.

Kenneth Gallagher - The Philosophy of Knowledge

-

Locke's Enquiry, Innateness, and Teleology

Unfortunately, I don't really recall. I want to say it's mostly Book II, maybe a bit in Book I. I recall the part about rebutting the potency argument best from a lecture. I am pretty sure it's in there, but it might have been in responses to later rationalist critiques of his program. -

Gödel Numbering in Discrete SystemsNot sure if this is what you had in mind, but in computation there are multiple systems that are computationally universal/Turing complete (e.g. Turing Machines, cellular automata, lambda calculus, etc.). So, when it comes to Kolmogorov Complexity, a measure of "algorithmic information," this measure is said to be equivalent to the shortest program that will output a string.

For example, ababababab has a short description, "print ab 5 times," whereas "a04bfsp" would necessarily have a longer description. But the languages do differ in meaningful ways, and one way is in determining the length of a program. It's an open question how best to deal with this, but the variance from switching languages is bounded (the invariance theorem). There are a ton of benefits to looking at how these systems are similar, and also how they are different (e.g. parallel processing and concurrent systems that allow for execution "out of order," the domain of process calculus.)

So that's one sort of example. And there is a real world application in that, when you try to turn the formalizing into a real computer, some systems are faster, or "more concise." -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

Caveat number 3: Goodman, in Ways of Worldmaking, makes the point that reduction is essentially a myth in science, and if that's so, he can claim for his relativism that rather than it being anti-science, it empowers him to take each science at "full force", to endorse the work of biologists and chemists, for instance, without treating them as second-class citizens whose science isn't quite as true as physics. That's appealing.

I'll have to check that out. It seems to me that the track record for reduction is quite weak, and that the empirical support for it is not particularly strong. It's a bit bizarre that it still has the status of "assumed true until convincingly proven otherwise," (especially since what would constitute such proof seems hard to imagine, you can always posit smaller building blocks). I think this is just from inertia and that fact that there are multiple ideas competing to replace it, not just one replacement paradigm.

In particular, I think the arguments in Jaegwon Kim's monographs are air tight (as do a lot of people). If superveniance physicalism works the way it is normally posited, then we have causal closure (and thus epiphenomenalism) but we also absolutely cannot have strong emergence. That brings us to a weird place where:

A. There can be no emergence vis-á-vis first person subjective experience so we seem stuck with panpsychism, denying we exist, occasionalism, etc.; and

B. Natural selection can never select on "what experience is like," because experience never affects behavior (causal closure), which both seems implausible due to how good evolutionary arguments are for "why what feels good feels good" (and the inverse), and causes a host of profound epistemic issues (highlighted by Plantinga and David Hoffman).

Kim points out that this only works for substance metaphysics (i.e. objects properties inhere in their constituents), and IMO this is just another piece of evidence against that sort of thinking (suggesting relational metaphysics à la scholasticism or process metaphysics).

But this is all veering off topic.

In short, you can separate their claim into two: the substantive claim, and an additional claim that all other versions are wrong. * You can take both claims quite seriously, accepting one and denying the other. If they want to fight about it, you're not fighting about the substantive claim, but about their claimed monopoly on the truth, which you have taken just as seriously and denied.

Well here, I think the metaphysics of truth come into play. I can see many great arguments for types of relativism. Plenty of thinkers who have a strong conception of an absolute morality still allow for cultural relativity. You can have "the Good," and still have it filtered through social context such that "being a good priest," differs from "being a good soldier," which differs from "being a good king." And culture can obviously affect how things are best explained.

Plus, you can make a case for pragmatic relativism, which addresses caveat 3. I don't think you have to default on the possibility of a language(s) that carve the world at the joints to say "we clearly don't have that, and so different languages are more appropriate for different contexts." After all, the absolute is not reality with appearances removed, but reality + all appearances.

So I agree with you. I don't see anything wrong with pragmatic cases for pluralism, and they don't need to entail that "everyone is always right." But I would not support the notion that "being right," simply has to do with game rules. For one, you can't ever get to an explanation for why games have the rules they do if you don't look outside of them.

People might talk about whether there's money in the bank or beer in the fridge, but they don't talk about whether money or banks or beer or refrigerators exist.

Wouldn't discussions of God fall into this category? That seems like a question of existence that is the organizing principle around which a great many people base their entire lives, and one with huge social and political implications.

The existence of "objective" moral standards would be another one that seems to be apparent in everyday life, often taking center stage. The same goes for the "meaning" and "purpose" of human life or humanity's telos.

The status of universals and numbers doesn't play nearly the same role that the aforementioned do, but people definetly seem interested in it. These creep into politics when we talk about education policy vis-á-vis mathematics. There are similar questions that have become quite politically relevant, i.e., "is gender or sex real?" or "is race real?"

And then you have the adoption of, at the very least, the post-modern lexicon by modern political movements. These days everything is about "deconstructing narratives," and there is "living your own truth," etc. The famous Giuliani retort: "truth isn't truth," appeals to "various ways of knowing," etc. suggest to me that pluralism is definitely relevant outside the context of the academy. I don't think this should be surprising, while most people in Scholasticism's heyday knew little of it, it had a major impact on the Church, education, and devotional life. Likewise, given the role "scientism" has as the dominant world view, it can't help but shape everyday experiences.

There may or may not be a truth out there, but how people comport themselves toward it is endlessly fascinating.

The idea of truth sitting "out there," also ends up presupposing some things if the view is that it lies outside us, existing "in-itself," waiting to be uncovered. In a mindless world, it seems to me that the truth/falsity distinction could have no content. Truth cannot be equivalent with being, since we can say truth things about what is not, e.g., "there is no planet between Earth and Mars." This is why Aquinas has truth inheritly bound up with a knower; "everything is known in the mode of the knower." The crucial distinction is that signs are always "how we know," whereas more pernicious forms of pluralism often seems to rely on the claim that "signs are what we know." But if everything is signs, "appearance," then there can be no real reality/appearance distinction.

This is why I like Robert Sokolowski's concept of "grasping the intelligibility of things," when it comes to epistemology. We cannot grasp a thing's intelligibility in every context, but this doesn't mean we cannot grasp their intelligibility at all.

The modern preference for potency over act comes up here too. Arguments for pluralism often focus on things like: "we could shift the pronunciation of every English word, or change this formal system in infinite ways, etc." Yet, in actuality, we don't have infinite systems, we actually have a fairly limited number of popular ones. But then I think there are reasons that explain actuality. -

Locke's Enquiry, Innateness, and Teleology

:up: good examples.

I guess if I had to sum up I'd say the issue is that describing organisms traits seems to require speaking to an additional sort of potency over and above the potency that exists in "all matter." I would tend to trace this to form not just because Aristotle does, but because form seems to explain how it is that matter within an ecosystem can be transformed into different organisms.

Basically, yes, it's true that the matter in a bunch of wild boar can be transformed into a leopard, so there is that potential there. However, the way this happens always involves matter in the form of leopards. It involves leopards eating the boar, incorporating their matter into their own bodies, and then mating, which bequeaths their form.

I don't want to get into the weeds on how this works at a fine grained scale, but Terrance Deacon's "Incomplete Nature," is one really great attempt at recovering formal cause (and thus telos) through thermodynamic processes, even if it might not get all the way there. I lean towards more of a process metaphysics, so I would tend to think of form more as morphisms between processes rather than arrangements of building blocks, which also gets around the reductive duplication of causes that was supposed to make formal cause obsolete in the first place.

Yeah, that is quite right. This innateness becomes key when it gets to defining freedom for Locke. D.C. Schindler identifies Locke as an exemplar of the shift in the conception of freedom from the classic/medieval focus on freedom as the ability to do the good (actuality) to freedom as the ability to do anything (potency). Locke needs innate preferences here because if you have freedom as just potency and no inclinations to guide that potency you end up with moral nihilism.

The Enquiry has a lot of gems, it's just sprawling (something he said himself). I really like Locke's reasoning and enjoy him, which is funny because I think he is wrong on a great many things, and wrong in an unfortunately influential way (mostly metaphysics). He's definitely my favorite British guy of that era. Hume sort of drives me nuts because I think he begs the question a lot (not in trivial ways, but it still bugs me). His definition of miracles would be one example of that. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.It's also occured to me that the thought you have previously imbibed and accepted will make it difficult (although by no means impossible) to see other thought clearly. This is perhaps not unlike optical illusions; if one has already seen the white and gold dress it becomes hard to see the black and blue one.

For instance, if you've read and accepted works like St. Maximus or the modern liturgical movement on prayer, then Wittgenstein's assessment of religious speech is going to seem very hard to swallow. Likewise, if you've imbibed Wittgenstein's view, it's going to be hard to get a good perspective on the aforementioned or perhaps to justify bothering to try.

Well, is this like optical illusions, where the rabbit and duck are both there for us to see? It depends. I have no problem saying some positions have some rather glaring flaws in some respects. There can be multiple good ways of photographing something, but this doesn't preclude that leaving your finger over the lens is a bad way. -

Aristotle's Metaphysics

Yup, he addresses those precise issues. They are why the answer is a qualified "yes." I think his reasoning is fairly straightforward, so it's probably best to let him speak for himself in Book X.

I do think there are some holes there that Aquinas fills in in the "On the Human Good," section of the Summa Contra Gentiles, but that is not as straight forward of a read (I personally dislike Thomas' style) or as short. -

The Self-Negating Cosmos: Rational Genesis, and The Logical Foundations of the Quantum Vacuum

I have not found an officially recognized operator, mathematical or logical, that decomposes a 0 into -1 and +1. The normal way of using the logical NOT operator is (NOT 0 = 1, or NOT 1 = 0), but what I am saying is that there needs to be a version of the NOT operator that: (NOT 0 = -1, +1), (NOT -1 = no effect, NOT +1 = no effect).

Can't help you there. I found this article on sublation interesting but I can't fully understand it: https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/Aufhebung#the_mathematics_of_yin_and_yang

I have thought of this in terms of division before. For a long period, it was thought that division by zero should result in infinity. The intuition here is that, as you reduce the denominator, the result gets larger and larger, tending towards infinity. But of course, there are some very well grounded reasons for making division by zero undefined instead, although some programing languages (e.g. DAX) still have division by 0 = ∞ due to their use case.

Anyhow, when we look at what happens when we approach 0/0 an interesting thing occurs. If we start with one as the numerator, and keep reducing the numerator towards zero, our number gets closer and closer to 0. On the flip side, when we keep reducing the denominator our result will tend towards the infinite. If you reduce both equally you get something like:

1/1 = 1

0.1/0.1 = 1

0.01/0.01 = 1

0.000....1 / 0.000...1 = 1

A (maybe too simplistic) way to think of this might be "the amount of nothing is no space." No nothing is something, but it's a sheer nothing that, occupying no space, can't vary along any dimension, making it contentless.

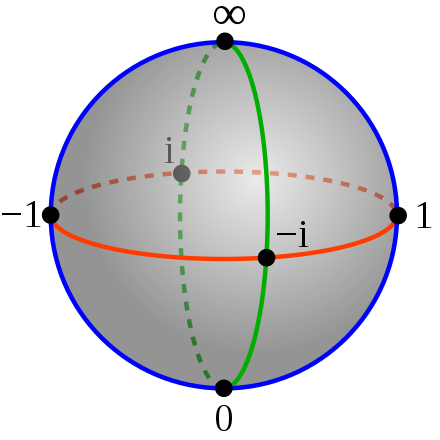

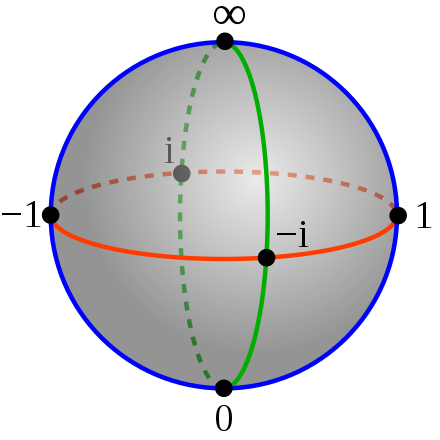

There is an idea going back to the Pythagoreans and developed by the Cappadocians and St. Maximus that number runs in a circuit. For the Pythagoreans, number proceeded from 1, unity, to the "myriad" before returning to unity. For some Christian thinkers (e.g. Origen) multiplicity itself was problematic, the result of the Fall. You get multiplicity when divine union is frustrated. So all of world history becomes the fall into multiplicity and the return to union. For Maximus though, the multiplicity remains important. Rather, the circuit, from unity to maximal division and back around to unity is itself a unity, but one that contains within its perfection multiplicity (and thus the value of individual persons).

Anyhow, systems where number loops back on itself exists in more formal terms, e.g. the Reimann Sphere.

You are probably familiar with functions that take the number line into itself. An example is $f(x)=1/x:$ it takes a number $x$ from the number line as input and returns $1/x$ as output. Unfortunately, the function is not defined at $x=0$ because division by $0$ is not allowed. However, as $x$ gets closer and closer to $0,$ $f(x)$ gets closer and closer to plus infinity if you're coming from the positive side, or minus infinity if you're coming from the negative side. If you could treat plus and minus infinity as one and the same ordinary point, then the function could be defined at $x=0$ and would be perfectly well behaved there. You can also define functions that take the plane into itself (the complex function $f(z)=1/z$ is an example) and again they may not be defined at every point because you have division by 0. However, by treating infinity as an extra point of the plane and looking at the whole thing as a sphere you may end up with a function that's perfectly tame and well behaved everywhere. A lot of complex analysis, the study of complex functions, is done on the Riemann sphere rather than the complex plane.

https://plus.maths.org/content/maths-minute-riemann-sphere

Also maybe of more relevance, there is this paper addressing your same topic: https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9809033

You might find the physicist David Bohm's stuff interesting too: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10701-012-9688-y#:~:text=Bohm%20suggested%20that%20order%20is,difference%20logically%20prior%20to%20similarity. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

First order predicate calculus does not render ontological conclusions.

Be charitable here.

I'm trying, lol, maybe I missed the point. Well, you can see the direction I was thinking in anyhow.

On the account you gave, it would be best to remove the inconsistencies

I don't see it that way. For an example of my thinking on this, some Hindu philosophy seems to embrace

the excluded middle. I don't think it would be charitable to try to iron this out in translation, because it wouldn't be taking the ideas seriously. I guess in some cases it seems more charitable to just say, "I hear you but I think you're wrong." -

Aristotle's Metaphysics

Starting where Aristotle does, with man, do we know what it is to be a man? What is the final cause, the telos of man? The question asks us not simply to give an opinion or account of it, but to know it by having achieved it, by the completion of our telos. Aristotle begins by saying that all men by nature desire to know. Is the satisfaction of that desire our telos?

The question of the telos of man is the question of self-knowledge. Socrates said his human wisdom is knowledge of ignorance. This is not expressed as an opinion but as something he knows. Is Aristotle’s wisdom, like that of Socrates, human or is it divine?

I know this is an old thread, but if you only got around to the Metaphysics, this is really discussed most in detail in Book X of the Ethics. It isn't a long book, but if you're just curious on this question you could probably get away with just reading Book I and Book X. Aquinas has a very good commentary on Book X.

But, with some caveats, the answer to the bolded is "yes." There are many ways to live a good, flourishing life, but the life of contemplation is highest and most divine. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.

If you're reading academic philosophy, there are forms of this. When reading postructuralist inspired literature I play a game I call "reciprocal co-constitution bingo". In which the author adopts phrases like "affect and be affected by", "in and through", "unable to imagine without", "always already". I get a point for every phrase like that

:lol:

I think you hit the nail on the head in that post. But this is a tough one for me because I see a lot in favor of systematic philosophy, of having everything hang together such that ethics and aesthetics flow from metaphysics and epistemology, etc. This is what makes Platonism and Aristotle so appealing. But the more systematic (or "anti-systematic") your philosophy is, the more you're going to want to bring it everywhere. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

Logic does not have ontological implications.

To be fair, is this obvious? I think for most "naturalists," there is going to be a path between "how the world is," and "what exists" and human logic. For those who embrace the computational theory of mind, which is still fairly dominant, parallel stepwise logical operations are what philosophy, human logic, language, and perception all emerge from. For those that buy into theories that explain physics in terms of computation, the universe is a sort of quantum computer.

And then for other schools the link is close too. For ontic structural realism, the world is a sort of mathematical object. For Hegelians, ontology is the objective logic. For much of the classical tradition, Logos is key to explaining "what there is."

For my part, I've always understood full deflation and anti-realism much more than any sort of split. I can see where these guys are coming from. I have never been able to fully wrap my mind around "splits" that involve naturalism with scientific realism on the one hand, but then full deflation on the other (i.e. truth as defined by games, or games as wholly intelligible in isolation from the world). To my mind at least, the scientific realism seems to suggest both an explication of the evolution of human logic and the idea that the formalizations of science really do "carve up the world at the joints."

But I do know a lot of naturalists still maintain a sort of Kantian dualism that allows for this sort of split

I don't think many people arethat reductive.

Well, IME, they certainly can be, but they tend to be reductive while embracing a different school of philosophy, where logic and language ultimately are reducible to particle physics—eliminitive materialism and all.

I get the impression you won't disagree with what I say and maybe you have been just attacking this truncated version of use you briefly mentioned which is not intuitive to me.

Yeah, I think the insight that meaning comes from use is a stellar one. The issue is, like you said, truncation, what counts as "use." Maybe it's just the stuff I've read, but some of it seems very behaviorist, a sort of arch empiricism where subjective experience can't be part of explanations because it cannot be objectively observed. As another sort of example, from a guy I like on a lot of things, but who seems to have a truncated view of use there is Rorty. I don't have any qualms with his attack on certain notions objectivity, but rather the claim that it is impossible to ever see how language "hooks on to the world," because of how it is bound up in social practice. Sellars on how facts are bound up in language might be another one. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

I would say it is generally taking arguments in the strongest, most compelling sense possible. However, if one starts to think that the most compelling sense of the arguments is to take them as fictions or games, when they are clearly not intended to be, it seems to go off the rails, no longer fulfilling its intended function. Foisting pluralism onto anti-pluralist positions sort of ignores what the non-pluralist is actually saying.

This is why I don't think Davidson's formulation is at all appropriate without plenty of caveats. Taken to an extreme, you can "maximize agreement," by simply taking everyone you disagree with as presenting artistic fictions. -

What do you reckon of Philosophy Stack Exchange ?I have used Stack Exchange for math, physics, and biology. It seemed pretty good. Used the theology one a few times; it was bad. The ubiquitous problem of Calvinists replying to everything that it is "unbiblical."

-

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun Stuff

The debates about univocity of being can apply between parties or within the thought of a single party, but quantifier variance occurs between two parties using two different notions of quantification. If the two parties have five different sub-quantifiers, and they agree on all of them, then quantifier variance is not occurring. ...All of this is also reminiscent of the duplex veritas debates of the Middle Ages.

:up: yeah, you're right. I wrote that during a bout of insomnia. My thinking was, if you assume QV, then when people who embrace those sorts of systems have disagreements, in a way, QV seems to assume that they are either wrong in their metaphysics or else not saying what they are saying. So the original example I thought of was comparing something like the classical Christian tradition to Shankara. In ways, the conception of infinite being is similar, but Shankara denies the existence of finite being, it being entirely maya—illusion. If QV is maintained by a third party, it seems like they can't take either of these claims in the way they are intended, which doesn't seem charitable.

I had a similar discussion with Joshs re truth being true withing a given metaphysics versus being true universally. It seems to me that if you tell a lot of people, "yes, what you're saying is true...but only in your context," you're actually telling them that what they think is false, because they don't think the truth is context dependent in this way.

What I would say is that the bolded part leads to a more thoroughgoing conceptual relativism, but the latter option is still a form of conceptual relativism. It's just that in the latter case both candidate meanings do a good job, and an equally good job, of carving at the joints.

I guess my intuition, which might very well be wrong, was that if they do an equally good job then there would be an morphism between them, and so it's pluralism of a limited type—perhaps the way some models for computation end up equivalent. -

Was Schopenhauer right?

Me, I think the argument can be made that he was 'the last great philosopher' (although I'll leave it to someone else to actually write it ;-) )

The guy who does the Great Courses' modern phil survey course makes this point. He is talking about Hegel, but the two were contemporaries and even taught across the hall from one another for a period. He says Hegel was the last great philosopher in terms of creating an all encompassing system (aesthetics, ethics, politics, metaphysics, epistemology, etc.) Others since have had careers that touch on all these eras (although even that is rare these days) but they don't build them off one another and make them hang together as a whole. I think it's fair to say this sort of thing could be said of Schopenhauer's thought too.

For a more recent candidate, there is Ferdinand Ulrich, who is still alive. I haven't made it very far with him but since a number of people who know their philosophy extremely well have described him with all sorts of superlatives I will try to get there. I take it he is systematic in this way, although not nearly as prolific as Hegel. Despite some famous people singing his praises, he hasn't really broken out in popularity, which does seem somewhat essential to being "great." The type of philosophy he does hasn't been in vouge for a while, but that might change. -

The Self-Negating Cosmos: Rational Genesis, and The Logical Foundations of the Quantum VacuumThe core idea surrounding negation is very reminiscent of Hegel's Logic. A core idea there is that sheer, indeterminate being itself collapses into nothingness, being itself absolutely contentless. The result is a passing back and forth between being and nothing, the sublation of nothing into being, resulting in becoming. From here he continues to move on to various other aspects of reality: quality, quantity, finiteness, infiniteness, etc. There has been some quite interesting work on trying to this through category theory - https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nameiwillforget/hegel-in-mathematics/main/Hegel_in_Mathematics.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjrvvnt7pyGAxVe_8kDHZWoDDg4ChAWegQIBBAB&usg=AOvVaw0R7FhneDSExy6d0pEv7Mdy

The Logic is a bear, but Houlgate's commentary is a bit easier. The Being/Nothing chapter is available here: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://phil880.colinmclear.net/materials/readings/houlgate-being-commentary.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwividrY65yGAxUSJTQIHcJcDJkQFnoECCwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0NPBNROaaCut1CwliwJj6N

You might find Spencer Brown's Laws of Form interesting here too. There is actually a neat overlap between Hegel's conception and parts of information theory (which is of course very influential in modern physics). An endless string of just 1s or just 0s (or the same 1 or 0 endlessly measured can contain no information). It's the differentiation that allows for a signal to have content.

If you think about this in analog terms, you can think of a wave with infinite amplitude and infinite frequency. As you increase the frequency, the peaks and troughs begin to cancel each other out. At the point of infinity, you end up with total cancellation, a silence, but this is a pregnant silence. There is perhaps an analogy with quantum information here, where an infinite range between 1 and 0 exists prior to collapse.

I find this image goes quite well with Eriugena's conception of God as "nothing through excellence," (the pregnant silence of the pleroma) as opposed to his "nothing through privation." Eriugena is sometimes called to "medieval Hegel," there is some strong similarities there.

Floridi also has some interesting stuff on information theory in ontology in his Philosophy of Information, but that is also a very dense work. -

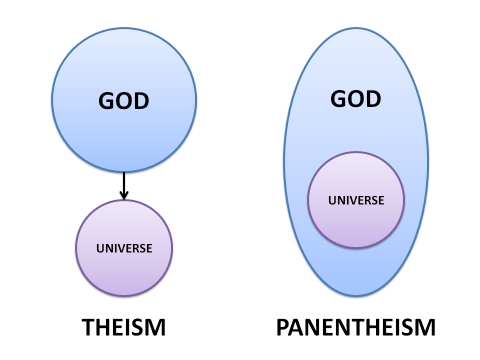

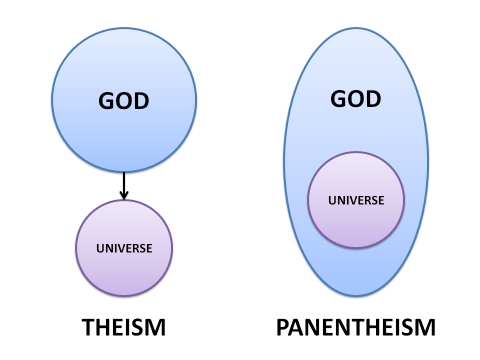

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffBTW, here might be a helpful example. Consider the panentheistic view that underscores Eriugena, Ulrich, etc.

This image is helpful, but one should bear in mind that the outer circle in the classical tradition really should be infinite, without border, we just can't draw it this way.

The idea of different sorts of being, of analogy being the only way to tie them together is sort of like this: to be for finite being is to be contained within the inner circle. Infinite being is in the inner circle, but it isn't contained in it, it transcends it. Everything is part of the outer circle in some sense. The outer circle is generally the domain under consideration in metaphysics.

This is, in some ways, an inadequate image. It misses the distinction that subsistent relations only exist in God (Exodus 3:14).

So, are we simply switching to domain when we discuss different types of being? I don't think so. If the domain under discussion is the inner circle then infinite being is included but also transcends the domain. If the domain is the outer circle, then entities in the inner circle stand in a different relation to the whole, hence the "different sort of existence" (and bear in mind here that the ontology generally employed here is inherently relational.

The "is" of predication, identity, and existence are not separated out in the same way in this tradition. In part, this is because they were seen as deeply related. Given the view that things just are their properties (which are relational), a not unpopular view in contemporary metaphysics, the the sum total of what can be predicated of a thing is its identity, or at least something very close to it. Consider Leibniz Law: ∀F(Fx ↔ Fy) → x=y

Likewise, if existence (or actuality) is simply another predicate, then the "is of existence" is deeply tied to the "is of predication" which in turn is deeply related to the "is of identity." Finite existence then is of a different type in that finite things can be defined in terms of all other things, and indeed their properties and identity are bound up in this relationality. They are also mereologically distinct due to the principle of divine simplicity (a major motivator here).

This doesn't quite capture the idea of God as "nothing through excellence," (nihil per excellentiam) versus the "nothing of privation," (nihil per privationem), which is also key to the distinction. I do think this is a distinction in existence that flows from the ontology itself though

and cannot be reduced to differences in language.

In such a view, there is no Porphyryean tree that has infinite and finite being alongside each other. The image might mislead on this front. God is being itself whereas finite being has being through participation in infinite being. For God alone, existence and essence are the same. -

Freddy Ayer, R. G. Collingwood and metaphysics?

I'm not now convinced by any of this. While the context in which a proposition occurs may be useful in understanding its meaning, and perhaps the reasons for its being stated, its truth will be independent of this context. The laws of motion formulated by Isaac Newton were accepted as science because they fit the facts, quite independently of the story about the apple in his orchard. Or indeed anything else about Newton's life or the society he lived in

I think you're right, although there also is a sense in which Newton's Laws are only an answer to a certain sort of question. Something like: "given we observe x,y,z..., what will happen next." It does not seem to answer the question of "why" we observe what we do. Various thinkers, Hegel, Cartwright, etc. have gotten at this over the years. But as you say, the truth relative to what they can answer seems quite independent of the question.

You can turn Newton's Laws into the answer for "why" questions, but this will tend to involve positing "natural laws," as casually efficacious entities that sit "outside" or "above" the universe and dictate its evolution. This is indeed exactly how they were viewed during Hume's time, but as Hume shows this opens them to a host of critiques.

Anyhow, on the topic of positivism, I have always found it fascinating how important Newton was for them as an exemplar of what science (and so all knowledge) should be. After all, there was this huge focus on falsification, but Newton's Laws were falsified in astronomy almost immediately. Orbits simply didn't line up with his laws. But we didn't abandon the theory, rather we posited hitherto unobserved planets with large masses that were shifting the orbits of the outer planets. This, of course, ended up being correct. And then there is the issue of multiple bodies, which shows the laws to be an idealization, although but maybe that insight is easier to fold into the positivist project. -

Wittgenstein and How it Elicits Asshole Tendencies.

I'd be interested if you could cite some references for earlier philosophers works which treat of "how the knowing subject affects knowledge". I'm not contesting your statement or claiming there are no such philosophical works or passages of work; I just can't think of any, and it seems like it should be interesting to see what such philosophers had to say about it.

Consider the ubiquitous maxim: quidquid recipitur ad modum recipientis recipitur, "whatever is received is received according to the manner of the receiver." This is pretty much an axiom in scholasticism and amounts to "people only understand in the mode they are capable of understanding." This is used to apply to both the universal structure of human understanding as well as learned/social constraints on the reception of ideas.

Another way this is put is "cogitum est in cognoscente secundum modum cognoscentis", which means "a thing known exists in a knower according to the mode of the knower."

Both these phrases are popularized by St. Thomas but you can find very similar ideas in Boethius centuries earlier, e.g. the contrast between the human understanding of Providence and the Divine in the Consolation, and plenty of other places aside.

Just off the top of my head, this sort of investigation shows up in Thomas' commentary on Boethius' De Trinitate, with the differentiation between processual, discursive human ways of knowing and the divine simplicity (this plays off Boethius' conception of eternity, that everything is present to God as a unity). The idea that truth is inheritly bound up with minds and is not simply reducible to being in a straightforward manner is addressed in the Disputed Questions on Truth. A view at odds with naive realism would be Thomas' theory of "intentions in the media," and the related concept of virtual signs worked out in Poinsot and Cusa. There are parallels between intertextuality and Al Farabi and Avicenna too. And then Thomas addressed if we know things or simply our ideas of things (indirect realism) in Question 84 of the Summa, as well as some other places, anticipating Locke, Hume, and Berkeley to some degree. Such a view wasn't unimaginable, rather it is rejected on the grounds that ideas and signs are "that through which we know," rather than "that which we know;" a position contemporary philosophy largely has wandered its way back to.

Edit: one source of this misconception might be that some scholastics do maintain that the "senses do not error," which can be read out of context in a way different from what is intended. The point being made is generally that errors are in judgements. It's asynthea, Aristotle's category for propositional knowledge, where falsity crops up. So the point is that we cannot have a sort of "false awareness." If you see or hear something, you are definitely seeing or hearing. Judgements about what you see and hear are where error come in. -

Quantifier Variance, Ontological Pluralism, and Other Fun StuffAnyhow, on the original topic, the idea that QV is a sort extension of the principle of charity seems wrong. Why? Because many individual thinkers argue for different types of "existence" within their metaphysics/ontology. In general, QV is framed using examples based on two different people debating what "exists" using supposedly "different languages."

However, the idea that there are different "types" of existence (e.g. exist vs subsist, actualism, etc.) is often presented as part of a single comprehensive theory, one ostensibly using a single language and focusing on a single domain (normally "everything") For example, when Eriugena discusses his five modes of being, he clearly is intending one domain and not using "different languages," despite lines to the effect of "to say man exists is to say logoi do not exist (in the way that man 'exists')."We could consider here Meinong, Parsons, etc.

But it hardly seems in line with charity to presuppose that the positing of these distinctions in "ways of existing" (or levels/degrees of "reality") is always just a confusion of language. This is basically saying that these philosophers are:

A. Wrong and certainly not making real distinctions about how things are in the absolute sense they seem to be claiming.

B. Confused and obviously either varying their language or domain. This is essentially assuming that they must be making a mistake regardless of what their argument/theory looks like.

B in particular is why I think the linguistic turn often leads to a failure of the principle of charity. To simply assume that a whole swath of discussions in philosophy must only arise from philosophers' "confusion," rather than real problems is not charitable. At its worst it's question begging. For example, to say that Przywara must be switching languages or domains with the analogia seems to be saying he is wrong in an important way, or even moreso, just refusing to take his thought the way it is intended.

Second, multiple uses of "exists" or distinctions of "more/less real," do not seem to be to entail any sort of relativism or anti-realism. It is rather Hirsch's move to "resolve" disputes by reducing them to language that threatens this.

This definition, at least taken in isolation, seems to avoid the issues above to some degree. "...either because there is no such notion of carving at the joints that applies to candidate meanings, or because there is such a notion and C is maximal with respect to it." It is more the bolded part that leads towards relativism, not different uses of "exists/subsists/etc."

Edit: To clarify - in terms of other explanations that cannot be explained by "the human sensory system, psychology, neuronal structures/signaling, etc."