Comments

-

Godel, God, and knowledge

If you disagree on logic's relation to math, then start with what you think are the logical tools of Gödel's theorem — Gregory

You only need these tools: knowledge about Gödel numbering, knowledge about formal systems, and the law of the excluded middle.

Did you even bother reading the Wikipedia article? It's not that long considering the difficulty of the subject.

Anyway, here is just one part of it:

Gödel noted that statements within a system can be represented by natural numbers. The significance of this was that properties of statements – such as their truth and falsehood – would be equivalent to determining whether their Gödel numbers had certain properties. The numbers involved might be very long indeed (in terms of number of digits), but this is not a barrier; all that matters is that we can show such numbers can be constructed.

In simple terms, we devise a method by which every formula or statement that can be formulated in our system gets a unique number, in such a way that we can mechanically convert back and forth between formulas and Gödel numbers. Clearly there are many ways this can be done. Given any statement, the number it is converted to is known as its Gödel number. — Wikipedia (Gödel numbering)

If the Gödel statement were meaningless, then we would not be able to construct it through Gödel numbers.

The Gödel statement is a meaningful statement since its corresponding Gödel numbers can be constructed. Therefore, it's either true or false, in the same way as a statement such as “10001^26278283 is prime” is either true or false, but not meaningless:

The Gödel sentence is designed to refer, indirectly, to itself. The sentence states that, when a particular sequence of steps is used to construct another sentence, that constructed sentence will not be provable in F. However, the sequence of steps is such that the constructed sentence turns out to be GF itself. In this way, the Gödel sentence GF indirectly states its own unprovability within F.

To prove the first incompleteness theorem, Gödel demonstrated that the notion of provability within a system could be expressed purely in terms of arithmetical functions that operate on Gödel numbers of sentences of the system. Therefore, the system, which can prove certain facts about numbers, can also indirectly prove facts about its own statements, provided that it is effectively generated. Questions about the provability of statements within the system are represented as questions about the arithmetical properties of numbers themselves, which would be decidable by the system if it were complete.

Thus, although the Gödel sentence refers indirectly to sentences of the system F, when read as an arithmetical statement the Gödel sentence directly refers only to natural numbers. It asserts that no natural number has a particular property, where that property is given by a primitive recursive relation. As such, the Gödel sentence can be written in the language of arithmetic with a simple syntactic form(...) — Wikipedia (Gödel incompleteness theorems)

That's a (very) brief summary of it.

If you want to know more, look it up. -

Godel, God, and knowledge

The Gödel statement is not a set, it's a statement.

It references itself, but unlike other statements that can be classified as meaningless, like the liar statement, it must either be true or false, because it's a mathematical statement.

Here you have a more detailed explanation -

Godel, God, and knowledgeI told you what I thought of it. It does not mean anything mathematically because it refers back on itself, a move of logic, not math. — Gregory

Do you know about Gödel numbering? If so, you should be able to understand why the Gödel statement is a mathematical statement. -

Godel, God, and knowledgeWrong, here's what Russell actually did say about the barber paradox:

You can modify its form; some forms of modification are valid and some are not. I once had a form suggested to me which was not valid, namely the question whether the barber shaves himself or not. You can define the barber as "one who shaves all those, and those only, who do not shave themselves". The question is, does the barber shave himself? In this form the contradiction is not very difficult to solve. But in our previous form I think it is clear that you can only get around it by observing that the whole question whether a class is or is not a member of itself is nonsense, i.e. that no class either is or is not a member of itself, and that it is not even true to say that, because the whole form of (the?) words is just noise without meaning. — Russell

The source is “The Philosophy of Logical Atomism”. -

The overlooked part of Russell's paradoxThat's the part I believe everyone has overlooked. I will try and show this clearly:

x, y and z, are sets that are not members of themselves. I am trying to form a set of these three sets that are not members of themselves. — Philosopher19

In your OP you mention 2 possibilities:

1.x, y and z not being members of themselves.

2. x, y and z being members of themselves.

Then you say: if 1 is true then U follows, If 2 is true then P follows.

I'm refering only to the second possibility, in which we assume that x,y and z are members of themselves, and then we see what that would logically entail (P).

You say:If x, y, and z are sets that are members of themselves, and I form a set of these three sets, to represent this, I can write something like: p = {x, y, z}. I cannot write x = {x, y, z}. — Philosopher19

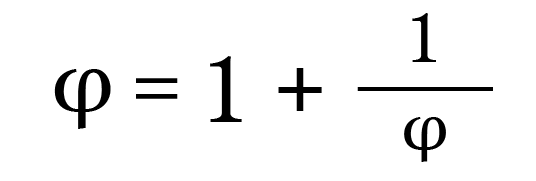

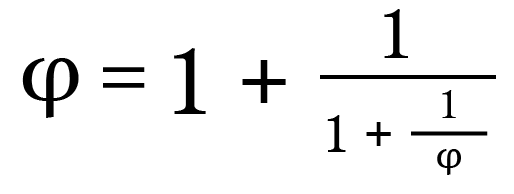

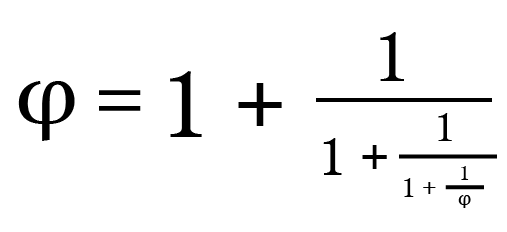

So you say if 2 is true, then x would be a member of itself, then we could write x={x,y,z} ,which we can't do because...well, you've given no reason to accept that yet, except that x would “contain itself twice”, which, if you mean what I said earlier (otherwise I don't know what you mean by that), is no reason for supposing that you can't have a set that contains itself as a member, in the same way as there is no contradiction about the golden ratio's continued fraction containing itself not just twice, but infinitely many times.

As for “the set of all sets that contain themselves”, regardless of whether or not such a set can be constructed, you have not yet given a good reason for maintaining that it can't be. -

Godel, God, and knowledge

That a professor of mathematics (Frege) got tripped up by this shows how poorly thought out his program was — Gregory

What “tripped up” Frege was Russell's paradox, not the barber paradox. -

Hole in the Bottom of Maths (Video)When Bertrand Russell told Gottlieb Frege about the 'barber paradox' it had a momentous impact on Frege's whole life work. — Wayfarer

If I may interrupt for a second, Bertrand Russell did not approve of re-stating his paradox as the barber paradox:

You can modify its form; some forms of modification are valid and some are not. I once had a form suggested to me which was not valid, namely the question whether the barber shaves himself or not. You can define the barber as "one who shaves all those, and those only, who do not shave themselves". The question is, does the barber shave himself? In this form the contradiction is not very difficult to solve. But in our previous form I think it is clear that you can only get around it by observing that the whole question whether a class is or is not a member of itself is nonsense, i.e. that no class either is or is not a member of itself, and that it is not even true to say that, because the whole form of words is just noise without meaning. — Russell -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?Hume would also probably say that our expectations are coincidental, too. Tomorrow you may wake up and expect apples to taste like watermelons. — god must be atheist

I'm not sure about that, it seems that if one accepts that the problem of induction also applies to psychology, Hume has no right to say things like these:

Nature, by an absolute and uncontrollable necessity has determined us to judge as well as to breathe and feel; nor can we any more forbear viewing certain objects in a stronger and fuller light, upon account of their customary connexion with a present impression, than we can hinder ourselves from thinking as long as we are awake, or seeing the surrounding bodies, when we turn our eyes towards them in broad sunshine. Whoever has taken the pains to refute this total scepticism, has really disputed without an antagonist, and endeavoured by arguments to establish a faculty, which nature has antecedently implanted in the mind, and rendered unavoidable. My intention then in displaying so carefully the arguments of that fantastic sect, is only to make the reader sensible of the truth of my hypothesis, that all our reasonings concerning causes and effects are derived from nothing but custom; and that belief is more properly an act of the sensitive, than of the cogitative part of our natures.

Because what he says about “Nature” either assumes the validity of induction when applied to expectations of similar expectations for the future, or is not justified by any reason, having neither certainty nor probability (that is: no reason to think it more likely than its negation), and therefore there is no reason to believe it.

Basically, we can't be sure that our nature will remain constant so as to always make us expect reasonable things. There is no rational justification even for the claim that I will probably not expect apples to taste like watermelons tomorrow. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?This is not true, I don't think so. The law of habit is not a law of causation. — god must be atheist

At the risk of making you lose your patience again... isn’t this relation between the sight of an apple and the expectation of a certain kind of taste, an instance of the causal law of habit?:

That’s not what Russell is saying, he’s saying that my expectation that when I see an apple in the future, it will taste like how apples usually taste and not like roast beef, is explained by the fact that I have always expected apples to taste that way in the past whenever I see them.

Thus, although in the past the sight of an apple (cause) has been conjoined with expectation of a certain kind of taste (effect), that gives no justification for the claim that it will continue to be so conjoined in the future.

Basically, expectations also fall prey to the problem of induction. — Amalac

We expect that we will expect apples to taste how they usually taste, because we are habituated to think that way, and so we expect that we won’t cease to expect them to taste like they usually taste, and not like ice cream in, say, the next 5 minutes. But even the truth of this claim depends on the validity of induction from particular instances, and so it is not even founded on probability:

if we take Hume seriously we must say: Although in the past the sight of an apple has been conjoined with expectation of a certain kind of taste, there is no reason why it should continue to be so conjoined: perhaps the next time I see an apple I shall expect it to taste like roast beef. You may, at the moment, think this unlikely; but that is no reason for expecting that you will think it unlikely five minutes hence. If Hume's objective doctrine is right, we have no better reason for expectations in psychology than in the physical world. — Russell -

The overlooked part of Russell's paradox

If x, y, and z are sets that are members of themselves, and I form a set of these three sets, to represent this, I can write something like: p = {x, y, z}. I cannot write x = {x, y, z}. — Philosopher19

Here you say they are members of themselves. If they are members of themselves, then x can be contained in x, right? So if set y and set z are members of x, what’s the problem with writing that the set x contains sets x, y and z?

If y and z are not members of x, then obviously they cannot be contained in x, but x can still be contained in itself.

But the key part of my post is that you cannot have a set of all sets that are members of themselves because it will result in at least one set being a member of itself twice. This is the overlooked part of Russell's paradox. — Philosopher19

Suppose x is the set of all ideas: since the set of all ideas is itself an idea, it contains itself. What’s wrong with that? I guess you are saying that if the set of all ideas contained itself, then the set of all ideas contained in the set of all ideas would also have to contain the set of all ideas again, and so on in infinitum. Well yes, but what’s wrong with that?

Using a mathematical analogy: the golden ratio’s infinite radical and its continued fraction contain themselves infinitely many times, and yet that does not give rise to any contradictions:

... and so on forever. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The past, however, is treated as something complete - done with so to speak - and thus, any talk of the past being an infinity immediately sets off alarm bells inside our heads. — TheMadFool

Is the series of negative integers, ordered from smallest to biggest (ascendingly), complete? Yes, in the sense that it ends with its last element -1. That’s true in spite of the fact that it has no first term.

Likewise, if the universe had an infinite past, the temporal series would “end” in the present moment.

My view is that the concept of time passing or elapsing is only applicable to finite intervals of time, so I disagree with Kant when, paraphrasing, he says: “If the universe had an infinite past, that implies that an infinite amount of time has elapsed“, I don’t think an infinite past would imply what he says it implies.

I just don’t see why we would want or need to say that an infinite amount of time elapsed, if the past were infinite. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

That's what Russell is saying would be the case if Hume was right (if I understood him correctly). -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

Yes, the expectation is not justified. — unenlightened

It's not just that we may be wrong about how future apples will taste, but also that we have no reason to expect that in the future we will even expect that they will have their usual taste instead of expecting that they will taste like ice cream.

I do not wish, at the moment, to discuss induction, which is a large and difficult subject; for the moment, I am content to observe that, if the first half of Hume's doctrine is admitted, the rejection of induction makes all expectation as to the future irrational, even the expectation that we shall continue to feel expectations. I do not mean merely that our expectations may be mistaken; that, in any case, must be admitted. I mean that, taking even our firmest expectations, such as that the sun will rise

tomorrow, there is not a shadow of a reason for supposing them more likely to be verified than not. — Russell

That is to say: if Hume is right, then not only is our expectation that the sun will rise tomorrow not justified, but neither is the expectation that we will continue to expect the sun to rise tomorrow justified.

If that's the case, Hume has no right to say such things as:

Nature, by an absolute and uncontrollable necessity has determined us to judge as well as to breathe and feel; nor can we any more forbear viewing certain objects in a stronger and fuller light, upon account of their customary connexion with a present impression, than we can hinder ourselves from thinking as long as we are awake, or seeing the surrounding bodies, when we turn our eyes towards them in broad sunshine. Whoever has taken the pains to refute this total scepticism, has really disputed without an antagonist, and endeavoured by arguments to establish a faculty, which nature has antecedently implanted in the mind, and rendered unavoidable. My intention then in displaying so carefully the arguments of that fantastic sect, is only to make the reader sensible of the truth of my hypothesis, that all our reasonings concerning causes and effects are derived from nothing but custom; and that belief is more properly an act of the sensitive, than of the cogitative part of our natures. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

Birds have a habit of singing in the morning. There may be a cause or many causes or none, but the singing is not caused by the habit of singing. — unenlightened

That’s not what Russell is saying, he’s saying that my expectation that when I see an apple in the future, it will taste like how apples usually taste and not like roast beef, is explained by the fact that I have always expected apples to taste that way in the past whenever I see them.

Thus, although in the past the sight of an apple (cause) has been conjoined with expectation of a certain kind of taste (effect), that gives no justification for the claim that it will continue to be so conjoined in the future.

Basically, expectations also fall prey to the problem of induction. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

(...)the law of habit is itself a causal law.

Therefore if we take Hume seriously we must say: Although in the past the sight of an apple has been conjoined with expectation of a certain kind of taste, there is no reason why it should continue to be so conjoined: perhaps the next time I see an apple I shall expect it to taste like roast beef. You may, at the moment, think this unlikely; but that is no reason for expecting that you will think it unlikely five minutes hence. If Hume's objective doctrine is right, we have no better reason for expectations in psychology than in the physical world.

Do you disagree with any of that?

By the way, I said “the law of habit” not “habit”, they are not quite the same thing. -

The overlooked part of Russell's paradoxI cannot write x = {x, y, z}. — Philosopher19

If y and z are members of x, then you actually can write it (if a set can be a member of itself). (I'm refering to the part where you say x is a member of itself).

You cannot have a set of ALL sets that are not members of themselves because it will result in at least one set not being included in the set. In other words, x will have to be in x, but it can't. — Philosopher19

The idea that such a set can't be constructed to solve the paradox does seem correct, as Russell's own solution (the theory of types) maintains.

But your reason for holding that there can't be such a set seems inadequate, all you are doing is to re-state the paradox: If x can't be in x then, by definition, it would have to be in x, since it would be a set that doesn't contain itself.

It's easier to understand with Grelling's paradox, which is similar to Russell's:

Suppose we define an adjective that describes itself as an autological adjective. For example: “polysyllabic” is a polysyllabic adjective, therefore it is autological.

And suppose we define an adjective that does not describe itself as a heterological adjective. For example: “monosyllabic” is not monosyllabic, therefore it is a heterological adjective.

But then the question arises: Is “heterological” a heterological adjective?

Let's say we maintain that it is, that means “heterological” is an adjective that does not describe itself. But if that's the case, then the adjective in question must not be named “heterological”, for that would necessarily imply that it describes itself. Yet we know that it is named “heterological”, therefore it can't be heterological.

Let's now maintain that it isn't heterological (that it's autological), meaning it does describe itself: That implies that it is heterological, since otherwise it would not describe itself. But obviously it is a contradiction to maintain that “heterological” both is and is not a heterological adjective. Therefore it can't be the case that it is autological either. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

However, he did not venture a causal theory empirical knowledge; he took the above principles as more-or-less self-evident. It is fair to dissect and question Hume's empiricist principles. It is also fair to ask whether those principles are more foundational than our causal intuitions. However, I don't think it is fair in this case to accuse him of illicitly helping himself to the very ideas that he questioned. That Hume imagined impressions being caused by their objects is a speculation. — SophistiCat

What do you make of the rest of what Russell says then?:

I doubt whether either he or his disciples were ever clearly aware of this problem as to impressions. Obviously, on his view, an "impression" would have to be defined by some intrinsic character distinguishing it from an "idea," since it could not be defined causally. He could not therefore argue that impressions give knowledge of things external to ourselves, as had been done by Locke, and, in a modified form, by Berkeley. He should, therefore, have believed himself shut up in a solipsistic world, and ignorant of everything except his own mental states and their relations. — Russell

Here Russell elaborates further on his view (the format here got a little messed up when I copied the text, sometimes that happens when using the quote function for whatever reason, so bear with it):

Empiricism and idealism alike are faced with a problem to which, so far, philosophy has found no satisfactory solution. This is the problem of showing how we have knowledge of other things than ourself and the operations of our own mind. Locke considers this problem, but what he says is very obviously unsatisfactory. In one place we are told: "Since the mind, in all its thoughts and reasonings, hath no other immediate object but its own ideas, which it alone does or can contemplate, it is evident that our knowledge is only conversant about them." And again: "Knowledge is the perception of the agreement or disagreement of two ideas." From this it would seem to follow immediately that we cannot know of the existence of other people, or of the physical world, for these, if they exist, are not merely ideas in any mind. Each one of us, accordingly, must, so far as knowledge is concerned, be shut up in himself, and cut off from all contact with the outer world.

This, however, is a paradox, and Locke will have nothing to do with paradoxes. Accordingly, in another chapter, he sets forth a different theory, quite inconsistent with the earlier one. We have, he tells us, three kinds of knowledge of real existence. Our knowledge of our own existence is intuitive, our knowledge of God's existence is demonstrative, and our knowledge of things present to sense is sensitive (Book IV, Ch. III).

In the next chapter, he becomes more or less aware of the inconsistency. He suggests that some one might say: "If knowledge consists in agreement of ideas, the enthusiast and the sober man are on a level." He replies: "Not so where ideas agree with things." He proceeds to argue that all simple ideas must agree with things, since "the mind, as has been showed, can by no means make to itself" any simple ideas, these being all "the product of things operating on the mind in a natural way." And as regards complex ideas of substances, "all our complex ideas of them must be such, and such only, as are made up of such simple ones as have been discovered to coexist in nature."

Again, we can have no knowledge except (1) by intuition, (2) by reason, examining the agreement or disagreement of two ideas, (3) "by sensation, perceiving the existence of particular things"

(Book IV, Ch. III, Sec. 2).

In all this, Locke assumes it known that certain mental occurrences, which he calls sensations, have causes outside themselves, and that these causes, at least to some extent and in certain respects, resemble the sensations which are their effects. But how, consistently with the principles of empiricism, is this to be known? We experience the sensations, but not their causes; our experience will be exactly the same if our sensations arise spontaneously. The belief that sensations have causes, and still more the belief that they resemble their causes, is one which, if maintained, must be maintained on grounds wholly independent of experience. The view that "knowledge is the perception of the agreement or disagreement of two ideas" is the one that Locke is entitled to, and his escape from the paradoxes that it entails is effected by means of an inconsistency so gross that only his resolute adherence to common sense could have made him blind to it.

This difficulty has troubled empiricism down to the present day. Hume got rid of it by dropping the assumption that sensations have external causes, but even he retained this assumption whenever he forgot his own principles, which was very often. His fundamental maxim, "no idea without an antecedent impression," which he takes over from Locke, is only plausible so long as we think of impressions as having outside causes, which the very word "impression" irresistibly suggests. And at the moments when Hume achieves some degree of consistency he is wildly paradoxical.

Also, regardless of how one views Hume's definition of an impression, it is clear that the law of habit is a causal law, and therefore Hume had no right to use it as an explanation for how the ideas of cause and effect come about, except as a sort of “reductio ad absurdum”, showing where seemingly good reasoning with sound principles has led him. -

Is Humean Causal Skepticism Self-Refuting and or Unsound?

Here is why I think Hume's account of causality is self-refuting: it presupposes a causal relation between perception and belief. Because, according to Hume, we perceive certain events constantly conjoined, we believe that they are causally related. The perception causes the belief. Hume even admits that belief in causality is very convenient, since it helps us make sense of experience. But this also entails a causal relation, since if the belief in causality helps us make sense of experience, then the belief causes us to make better sense of experience. — Noisy Calf

All that would prove is that Hume was inconsistent and could not follow his scepticism to the end. If that's your point, then I think you are right.

Bertrand Russell gave a very similar criticism, as follows:

The fact is that, where psychology is concerned, Hume allows himself to believe in causation in a sense which, in general, he condemns. Let us take an illustration. I see an apple, and expect that, if I eat it, I shall experience a certain kind of taste. According to Hume, there is no reason why I should experience this kind of taste: the law of habit explains the existence of my expectation, but does not justify it. But the law of habit is itself a causal law.

Therefore if we take Hume seriously we must say: Although in the past the sight of an apple has been conjoined with expectation of a certain kind of taste, there is no reason why it should continue to be so conjoined: perhaps the next time I see an apple I shall expect it to taste like roast beef. You may, at the moment, think this unlikely; but that is no reason for expecting that you will think it unlikely five minutes hence. If Hume's objective doctrine is right, we have no better reason for expectations in psychology than in the physical world.

(...)

Hume shrank from nothing in pursuit of theoretical consistency, but felt no impulse to make his practice conform to his theory. Hume denied the Self, and threw doubt on induction and causation. He accepted Berkeley's abolition of matter, but not the substitute that Berkeley offered in the form of God's ideas. It is true that, like Locke, he admitted no simple idea without an

antecedent impression, and no doubt he imagined an "impression" as a state of mind directly caused by something external to the mind. But he could not admit this as a definition of "impression," since he questioned the notion of "cause." I doubt whether either he or his disciples were ever clearly aware of this problem as to impressions. Obviously, on his view, an "impression" would have to be defined by some intrinsic character distinguishing it from an "idea," since it could not be defined causally. He could not therefore argue that impressions give knowledge of things external to ourselves, as had been done by Locke, and, in a modified form, by Berkeley. He should, therefore, have believed himself shut up in a solipsistic world, and ignorant of everything except his own mental states and their relations. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Spatial differentiation is perceivable/sensible, yes? (hm not sure "sensible" is the right word here) — jorndoe

What you say here reminds me of David Hume's view (as Bertrand Russell interprets him) that we percieve relations of time and place, although we do not perceive causal relations.

According to Kant, it can be proven that space is a necessary pre-condition (“anschauung”) of all perception. One of his arguments (though a dubious one) is that we can't imagine anything as not being in space, but can imagine empty space (space with nothing in it). Bertrand Russell interprets this as implying that Kant's space is absolute, not relational.

So, if we suppose that Kant managed to imagine absolute empty space, then it would seem that space could be perceived in the mind's eye, though not perceived in the world. But as Russell pointed out, it is hard to see how one could imagine space with nothing in it. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

I actually said, if you would kindly check, that an infinite number of years passed, not an infinite amount of time. — god must be atheist

Isn't an infinite number of years an infinite amount of time? I don't see how that distinction is important.

"A year passed after a point in time that marked the end of the previous year, in an infinite series." — god must be atheist

Surely, this doesn't answer the question: “Since when did infinitely many years pass up to the present?”

If I asked someone: “since when have 5 years passed? I expect them to simply answer: “since 2016”.

So if I asked you “since when have infinitely many years passed?”, I expect you to answer “since year X”.

So what's the value of X?

Perhaps you just mean that if the universe has an infinite past, then an infinite amount of time “exists” or “It is the case that the past is infinite”, which is fine by me, and doesn't fall prey to Kant's criticism. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

If you need to know how I defined "passed", which is a commonly used English term or word — god must be atheist

As it's commonly used, “passed” or “elapsed” implies a beginning and an end.

This sort of definition is the one I have in mind:Elapsed time is simply the amount of time that passes from the beginning of an event to its end.

(...) In simplest terms, elapsed time is how much time goes by from one time (say 3:35pm) to another (6:20pm).

That definition doesn't assume that the universe must have had a beginning in time, for if the universe has no beginning in time, I can still say for instance: 13.8 billion years have elapsed since the Big Bang happened to today. But I can't say: infinitely many years have elapsed since ??? happened to today.

If you say that time doesn't have to pass or elapse “since” some moment, then you are using the term in a way that's different from how it's usually used, hence why I ask you to tell me what you mean by that. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

“X amount of time passed” by definition implies that it passed since some point in the timeline to some other point in the timeline.

So if you say an infinite amount of time has passed up to the present day, then you must also say that it passed since some point in the timeline, otherwise I've no idea what you mean when you say an infinite amount of time “passed” -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

I did not say "It happened since never." — god must be atheist

Then since when?

I answered your question. — god must be atheist

I thought earlier you said the question wasn't even legitimate. But anyway, just tell me how you define the term “passed” (what I asked you before). -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

That doesn't answer my question.

“5 years have elapsed since 2016 to today” has a clear meaning for me, but “infinitely many years have passed since «never» to today” doesn't.

Something that happened/passed since “never” is something that in fact didn't happen/pass. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Time elapses “since” some moment in time (not necessarily an absolute beginning in time of the universe) “to” some other moment in time.

If not, then I don't understand what you mean by “passed”. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?And then it's clear that there are an infinite number of years that have passed already to the present day. — god must be atheist

...since when? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

I think we are being invited to consider this project to be logically incoherent; as opposed to merely practically impossible, like reciting the digits of pi forwards. Forwards, you'll never finish. Backwards, you will never have begun. — Cuthbert

There are rigurous proofs of the irrationality of π, so yes, that's logically impossible.

Following that example: We can never begin recting all the negative integers (from smallest to biggest), but that doesn't mean that there is no such thing as the set of all negative integers, likewise we can't recite all the digits of π, but that doesn't mean that there is no such thing as the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter.

Whether it's “enumerable” or not doesn't seem like a good criterion for determining whether it is possible for it to exist or not. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Do we have valid reasons to justify such differential treatment of space and time? Why is time (thought to be) in "motion" and space (thought to be) is "motionless"? — TheMadFool

Well to go back to Kant, when he's speaking about time passing he means that time has “elapsed”. Surely, it wouldn't make sense to say that space “elapses”.

Even the Oxford dictionary defines the term as only applicable to time:

Elapse: (of time) pass or go by.

At any rate, time is certainly not in motion in the same sense in which a physical object is in motion, right? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Witnessing indicates observation. To witness an object from outside its limits merely indicates observing the object’s spatial boundaries. — Mww

What is the boundary of the world then? I guess you mean something like the CMB? But just because we cannot see beyond the CMB, that doesn't mean that there's nothing “beyond” it, so to speak, only that we could never see it in the actual world (though we could in some possible world, unless there's something logically impossible about it).

Assuming the absolute validity of the principle, the only reconciliation is simultaneity, in which time is no longer presupposed, yet for which account is given. — Mww

So by simultaneously you don't mean “at the same time”, what do you mean by that then? Logically simultaneous?

There is no present. Questions predicated on impossibilities are irrational. — Mww

If there's no present, and an infinite amount of time has elapsed as Kant maintains in the first thesis, since when to when did it elapse? -

God as the true cogitoIt seems that the flaws of the argument in the OP are somewhat similar (I say this being very charitable of course) to those explained in this more interesting 9 minute video

-

God as the true cogito

How is that not contradictory? — Philosopher19

There's nothing contradictory about it (though the way Meinong expressed his ideas is peculiar).

But since it seems like that's not what you are talking about, I'm going to translate it so as to make it clearer: What we are interested in here is existence outside the mind, right? So in that sense, a merely imaginary man does not exist, and neither does a unicorn.

And it seems you are again confusing “is” as a copula with “is” as a synonym for “exists”: when saying “Sherlock Holmes is an imaginary character” that does not imply that one assumes that Sherlock Holmes exists in the same way I do.

Does a Sherlock Holmes at least exist as a character (perhaps in a story)? Yes. — Philosopher19

When most people talk about existence, it is usually implied that it is “outside the mind”. At any rate, Sherlock Holmes certainly does not exist in the same sense in which I exist.

If we take the absolute approach (no degrees), then no, you don't have existence. — Philosopher19

If we use Meinong's terminology, then yes, I do have existence. If you are not using that terminology, then clearly you are assuming here that existence is a predicate (“I have/ don't have existence”) and can therefore be refuted by Kant's objection.

All that “I have existence” (in Meinong's sense) means is that I exist, nothing more and nothing less. No degrees of existence involved here.

Descartes' I think therefore I am established that something indubitably exists. — Philosopher19

It established that thoughts exist (meaning: “there are thoughts” or “thinking is happening”), not that God exists.

But only God cannot be any more complete/perfect as a being. — Philosopher19

There are only 2 degrees of existence according to this “approach”: existing in the mind, and existing outside the mind, there is no other level of “perfection of existence”. So if God exists outside the mind, then God's existence is more “perfect” than the existence of a unicorn because unicorns don't exist outside the mind, but his existence is not more “perfect” than mine because I too exist outside the mind.

Plus:

No, you are now equivocating “is” as a copula and “is” as a synonym of “exists”. — Amalac -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

When you assume "...the universe was infinite towards the past...", you shouldn't be asking "...since which moment down to the present did it pass? Since when to when did it pass?" because that question, whatever else it is, presupposes a beginning, a starting point, to time - the "which moment", the"when" in "when to when". — TheMadFool

So you are saying that an infinite amount of time “passed” in that infinite past universe, but not since any particular moment in time. What do you mean by “passed” then? -

God as the true cogito

To be an imaginary human, is to exist an imaginary human? — Philosopher19

So, perhaps you are hinting at Alexius Meinong's distinction between existence and being (I'm going to charitably assume that), in that case I'd say a human that is merely imagined has being, but does not exist. If that's what you mean then yes, I agree.

To be a human on planet earth, it to exist as a human on planet earth? — Philosopher19

Yes, that's another way of saying the same thing.

Do you agree that to be imperfect as a triangle, is to exist imperfectly as a triangle? — Philosopher19

Things with imperfect triangular shapes exist.

Even if triangles existed outside our minds, as platonists hold, they would be ideal triangles, not imperfect ones.

Do you agree that to be imperfect as a being/existent, is to exist imperfectly as a being/existent? — Philosopher19

Once again, if you are following Meinong, all you are saying is that unicorns have being but don't have existence, since they only exist in the mind, whereas I have existence since I exist both as an idea in the mind and also outside the mind.

Note that you cannot say to be a square-circle, is to exist as a square-circle. Such a thing is impossible. Absurdities and contradictions exist, but what they describe (round squares) does not. By definition that which is contradictory is absurd or not true of existence. — Philosopher19

They have “being” in Meinong's terminology, yes (though this is a little more dubious).

Perfection = that which is perfect. The perfect being. That which perfectly exists. — Philosopher19

No, you are now equivocating “is” as a copula and “is” as a synonym of “exists”. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

You claim to have no problems with an infinite past but then you say you can't accept that "if the universe has an infinite past then an infinite amount of time must have passed". It doesn't add up. — TheMadFool

Oh dear, just answer the question: Assuming the universe was infinite towards the past, and that an infinite amount of time passed all the way to the present, since which moment down to the present did it pass? Since when to when did it pass? -

God as the true cogitoDo you think it's better to be in a truly perfect existence or not?

Do you think it's better to be God or not? — Philosopher19

Obviously yes, but I don't see how you go from that to «therefore God exists», since you say your argument is not like Anselm’s, or Descartes’s, or Leibniz’s...

B) Whatever's perfectly existing, is indubitably existing (just as whatever's perfectly triangular, is indubitably triangular). — Philosopher19

What do you mean by “perfectly existing”? I understand how a shape could be perfectly triangular (in our minds), but not how something could be “perfectly existing”. Either a thing exists outside the mind or it does not. If God did exist, then he would not exist more “perfectly” than I would (since all that means is that God exists both as an idea in the mind and also outside the mind, just like I). It is not comparable to triangularity because there are no degrees of existence outside the mind as there are degrees of a shape approaching an ideal triangle.

You could say God would have a more perfect existence than I in the sense that he would be better than me, but then you are no longer talking about a quality of “existence” in the same sense in which you were talking about a quality of “triangularity” which doesn't involve a perfect triangle being better (morally) than an imperfect one, you are just equivocating the meaning of “perfection”, it seems to me, and so your analogy breaks down. -

God as the true cogito

It is better to be the real God than to exist as just an illusion/image of God (the real God is better than all humans or image/imaginary/pretend gods). We are meaningfully/semantically aware that something perfectly/indubitably exists — Philosopher19

That’s quite the jump there, if you are trying to argue that God’s existence is analytic, that could only happen if God was a being whose essence involves his existence, his essence being all the predicates that could be truly asserted of him, these being God’s perfections (otherwise if I take your argument literally I can just say: it would be better for God to exist, but unfortunately not all great things are the case in this world).

This sort of argument fails if existence is not a predicate, for in that case “existence” cannot be predicated of God, therefore it can’t be part of God’s essence and the argument is invalid.

See my other post you ignored here:

The most effective refutation of such kinds of ontological arguments that I know of is the one invented by Kant: existence is not a predicate, or if you prefer Frege: existence is a second order predicate.

If that is true, then it makes no sense to think of existence as a “quality which is better to have”:

Suppose I express my idea of a blue apple by painting a picture of five blue apples. I point my finger at it and say, "This represents five blue apples." If later I discover that blue apples really exist, I can still point to the same picture and say, "This represents five real blue apples." And if I can't discover the existence of the blue apples, I can point to the painting and say, "This represents five imaginary blue apples." In all three cases the picture is the same. The concept of five real apples does not contain one more apple than the concept of five possible apples. The idea of a unicorn will not get more horns just because unicorns exist in reality. In Kant's terminology, one does not add any new properties to a concept by expressing the belief that the concept corresponds to a real object external to one's mind.

— Martin Gardner

Here is a (short) explanation of Frege's criticism — Amalac -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

SO the question arrises as to how accurately it represents Kant's argument. — Banno

Well, here's Kant's argument from my copy of the Critique of Pure Reason:

Suppose the world does not have a beginning in time. In this case, an eternity has elapsed until each given instant and, consequently, an infinite series of successive states of things in the world. Now, the infinity of a series consists in that it can never be finished by means of successive syntheses. Therefore, an infinite past cosmic series is impossible and, consequently, it is an indispensable condition of the existence of the world that it has had a beginning, which is the first point that we wanted to demonstrate. — Kant

It's perhaps not quite the same as Popper's interpretation, if taken literally, but it is very similar, and seems open to the objection I gave in the OP. -

God as the true cogito

First, if it works it does not show that the ontological argument for God does not work, it just establishes the devil's existence as well. — Bartricks

No, the point is that it's challenging the idea that it is better to exist than not to exist, since we naturally think that such a devil would be worse if it existed.

It is complemented also by the “no devil corollary” and the “extreme no devil corollary”:

The no devil corollary is similar, but argues that a worse being would be one that does not exist in reality, so does not exist. The extreme no devil corollary advances on this, proposing that a worse being would be that which does not exist in the understanding, so such a being exists neither in reality nor in the understanding. Timothy Chambers argued that the devil corollary is more powerful than Gaunilo's challenge because it withstands the challenges that may defeat Gaunilo's parody. He also claimed that the no devil corollary is a strong challenge, as it "underwrites" the no devil corollary, which "threatens Anselm's argument at its very foundations".

— WikipediaBut an omnipotent and omniscient being will also be omnibenevolent — Bartricks

How do you know that? Can you prove this claim? -

God as the true cogitoThere is also the devil corollary:

The devil corollary proposes that a being than which nothing worse can be conceived exists in the understanding (sometimes the term lesser is used in place of worse). Using Anselm's logical form, the parody argues that if it exists in the understanding, a worse being would be one that exists in reality; thus, such a being exists. — Wikipedia -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?Everywhere, counterintuitive implications everywhere? Should we just make stuff up? Drop sufficient reason (in this case at least)? Are we back to square one? A non-infinite "edge-free" universe? — jorndoe

I'd say we should follow Kant's view on this matter:

What lesson did Kant draw from these puzzling antinomies? He concluded that our ideas of space and time are inapplicable to the universe as a whole. We can, of course, apply the ideas of space and time to ordinary physical objects and physical events. But space and time themselves are not objects or events: they cannot even be observed, they are more elusive. They are a kind of framework for things and events, something like a box system, or a recording system, for observations. Space and time are not part of the empirical, real world of things and events, but are part of our mental equipment, of our apparatus to capture the world. The appropriate use that can be given to them is that of observation instruments: when observing any event we usually place it, immediately and intuitively, in an order of space and time. Thus, space and time can be considered as a frame of reference that is not based on experience, but is used intuitively in experience and is appropriately applicable to it. This is why we are inconvenienced when we misapply the ideas of space and time, and use them in a realm that transcends all possible experience, as we did in our two proofs on the universe as a whole. — Karl Popper

Amalac

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum