Search

-

A quandary: How do we know there isn’t anything beyond our reality?

So I'm trying to figure out how P1 would not automatically imply P3 at time t. — EricH

Yep. That we know p implies that it is possible to know p.

Technically, it's valid in any system in which the accessibility relation is reflexive - in which a possible world can access itself. So both S4 and S5.See https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A~5~9A||reflexivity.

The definition of ◇p in Kripke's semantics is that p is true in at least one accessible world. If we drop reflexivity, then p might be true here but not in any other world, and since only other worlds are accessible, it would be invalid.

Meta denies that p→◇p, a sentence which will be valid only if we do not include the world in which p is true in the list of accessible worlds. His account is valid only if we cannot access the world in which p is true. And in p→◊p, the world in which p is true is this world.

The technicalities are to a large extent unavoidable. In plain language, we might replace "accessibility" with "the worlds about which we can talk" and call the possible world we are in, the actaul world. Then:

The inference p → possibly p is valid only in modal systems where each world counts itself as possible, that is, where we can talk about the actual world. In Kripke semantics, “possibly p” means that p is true in at least one world about which we can talk. If you drop reflexivity, then we can't talk about the actual world, and so p may be true in the actual world but not in any world about which we can talk. So the inference fails. Since Meta denies p → ◇p, his view amounts to saying that the actual world is not among the worlds about which we can talk. But in p → ◇p, the world where p is true is simply this world.

The tense is not usually considered in modal logic. So we can for example talk about the possibility that you did not write the post to which I am replying, by talking about a possible world in which that was so. That's not the actual world, of course, but it's still a possible world.

Meta's confusion might be the result of thinking of accessible worlds as “counterfactual” only, never including the actual world. This seems likely. But for the rest of us, the actual world is considered to be one of the possible worlds. -

One Infinite Zero (Quote from page 13 and 14)

I'm just throwing some ideas out there, into the Aether, to see if any might stick :Chaos (lack of distinction, not deterministic)

Simplicity (One thing which is composed of itself)

0 dimensional entity (Distances are not real-Ill get to that in a sec)

the big bang (beggining of Two, or the great split)

The One (lack of distiction, Chaos, infinite, simple and unique)

The universe cannot expand "outward" because, according to physics, there is no external reference point or boundary outside of it. The universe is not expanding into a pre-existing space; rather, space itself is stretching. This means that distances between points within the universe are increasing, but there is no external space into which it expands. Thus space is not made of actual space.

If the universe is stretching the way physics describe(not outwards but "inwards"), space is not composed of space but rather the effect of phenomena on matter. — Illuminati

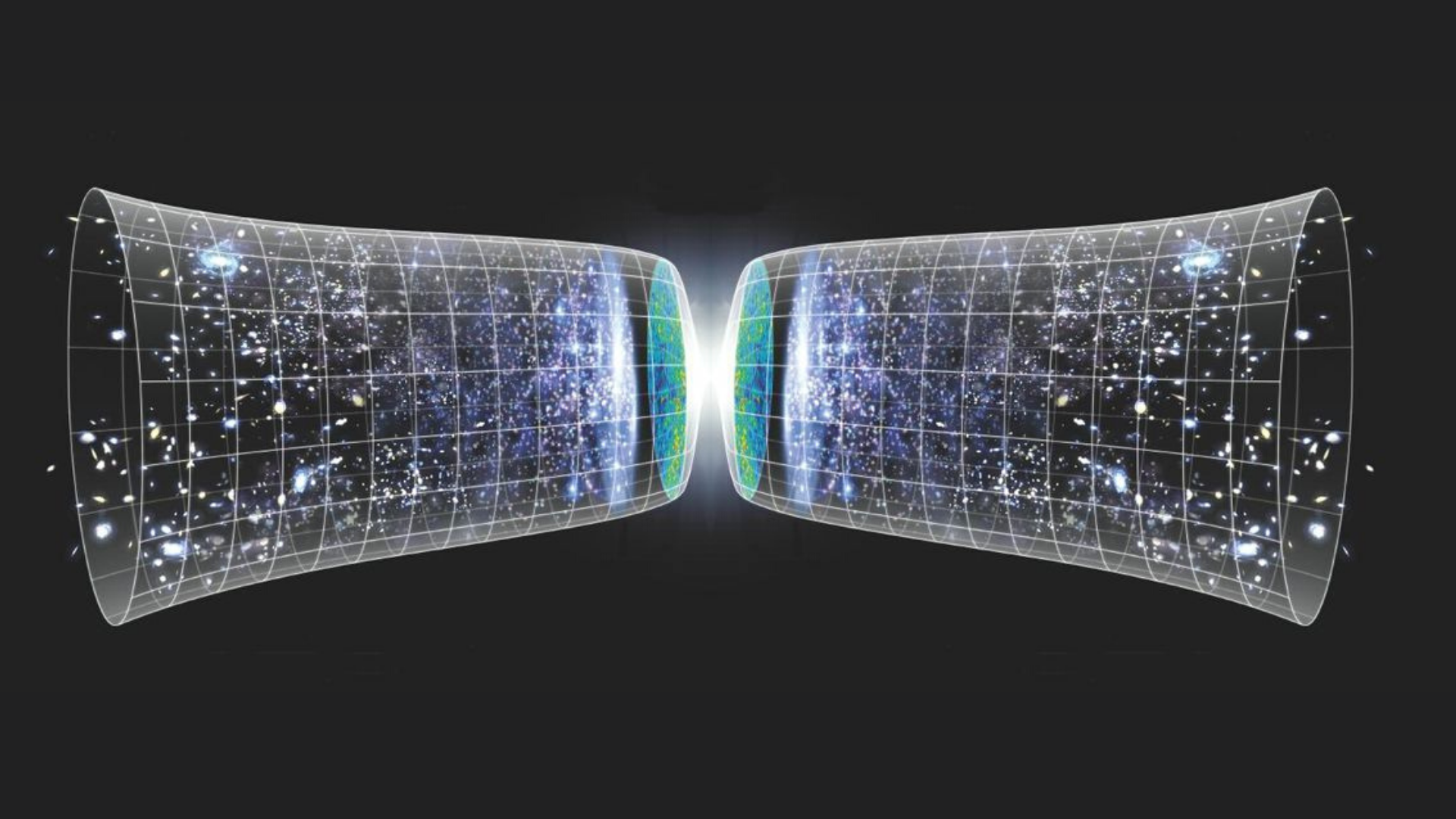

#A. "pre-existing space" : Space-Time is not a real thing, but an imaginary geometric model that scientists use to understand Change. Since it is Ideal, scientists can extend the model timeline into the future or the past {image below}.

#B. "space itself is stretching" I assume this is a metaphor, as-if space is an elastic substance. Space is not a material substance that could stretch & warp, but the infinite Causal Potential that makes the local Matter Effect possible?

#C. "effect of phenomena" : As you put it : space is the conceived effect of sensable phenomena, such as Matter, relative to other Matter, or that is changing its size or location. But apparently, the Cause of the effect is undifferentiated Chaos that voluntarily begins to differentiate its infinite Potential into multiple space-time Actual Things. If so, then Chaos possesses Will-power*1 or Causal Power, Desire, Inclination, Choice???

#D. "space is not made of actual space" : Not a metaphor, but a mystery. So, what is formless empty nothingness made of : Aether*2? Traditionally Chaos = randomness or nothingness or void. As you said "not deterministic", so is Chaos pure Chance? Without the willpower to choose, anything that can happen will happen??? Is space made from the causal willpower we call Energy/Change? :smile:

*1. Will :

"Schopenhauer identifies the thing-in-itself — the inner essence of everything — as will: a blind, unconscious, aimless striving devoid of knowledge"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_World_as_Will_and_Representation

Note --- Is "OIZ" similar to Schopenhauer's Will : more like a physical Force than a metaphysical G*D?

*2. Aether :

(or ether) can refer to the ancient Greek concept of the pure upper air breathed by gods, the personification of this sky deity, or a discredited scientific theory of a space-filling medium for light.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=aether

In the 21st century, the "aether" concept reappears in physics, not as the 19th-century luminiferous medium, but as the Einstein ether, a framework exploring a space-filling medium compatible with Einstein's theories that could potentially explain dark matter/energy.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=21st+century+aether

Note --- Not the Fifth Element, but the Only Substance (Aristotle/Spinoza)

SPACE-TIME BEFORE & AFTER BIG BANG

-

Language is Metaphorical and Materialistic

I have long assumed that many of our polarized disagreements on The Philosophy Forum are due to the "fact" that the common language of TPF, English, is essentially Materialistic (concrete & deterministic) and Metaphorical*1 (as-if), while the language of Science is supposed be factual : examining things as they really are (as-is) --- whatever that is. So, one party is talking about metaphysics (e.g. Mind) while the other is thinking about physics (Brain). Hence, some metaphysical (absolute) Materialists think they are making scientific (empirical) statements on a philosophical (theoretical*2) forum.

As far as I know, the only non-metaphorical language is Mathematics (abstract Logic). But when translated into colloquial forum posts, the logic of science becomes muddied with metaphors, which can be variously interpreted. The ambiguity of Quantum indeterminacy, may be why physicist Richard Feynman concluded, "It is safe to say that nobody understands quantum mechanics", and is mis-quoted advising his students to "shut-up and calculate". Einstein was also skeptical of probabilistic Quantum math, because it "made no firm predictions".

I know very little about the "Linguistic Turn"*3 in philosophy, but I suppose it developed due to the modern polarization of philosophical investigation, that followed the Enlightenment Period, with its rejection of religious authority. Hence today, the meaning of each word is debatable. The same dualistic --- black vs white ; right vs wrong ; material vs mental --- division in philosophy is also apparent in modern Party Politics. That's why I sometimes say that a thread has been "politicized" instead of "philosophized". The presumption here is that Philosophy should seek unity of belief --- to get closer to Truth --- instead of arguing for doctrine A against dogma B.

Typically, the polar beliefs in this forum seem to boil down to Materialism (empirical facts) vs Idealism (general principles). So, many of the recurring threads, such as the nature of Consciousness, eventually devolve into name-calling doctrinal debates instead of sharing plausible opinions. In my opinion FWIW, a pragmatic worldview will treat the external world as-if it is purely Materialistic. But when we begin to talk about Ideas & Meanings & Principles & Values*5, we are faced with the necessity for Idealism, as a practical way to understand the features of reality that have no material properties.

On this forum, since our language is mostly Metaphorical*6, we need to keep in mind that our opinions & beliefs cannot be expressed empirically or factually. So our metaphors should be taken with a grain of salt, and healthy skepticism, and presented with a dose of humility. My personal worldview is based on some empirical scientific "facts", but the most important aspects (to me) are based on non-empirical speculation. So I can't be too cocky in my assertions.

Is the forum biased toward metaphysical Materialism by its common language? :nerd:

*1. "Yes, language is materialistic in that it is a material system that is embedded in social and political economic structures."

"Yes, some linguistic theories suggest that all language is metaphorical. This is because words are not the thing itself, but rather a way to point to it."

___Google AI overview

*2. "A philosophical theory or philosophical position is a view that attempts to explain or account for a particular problem in philosophy. The use of the term "theory" is a statement of colloquial English and not a technical term." ___Wikipedia

Note --- Most of our forum assertions are Hypothetical, not formally Theoretical or Doctrinal, and neither True nor False, but expressions of provisional belief.

*3. "The term ‘the linguistic turn’ refers to a radical reconception of the nature of philosophy and its methods, according to which philosophy is neither an empirical science nor a supraempirical enquiry into the essential features of reality; instead, it is an a priori conceptual discipline which aims to elucidate the complex interrelationships among philosophically relevant concepts, as embodied in established linguistic usage, and by doing so dispel conceptual confusions and solve philosophical problems."

https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/linguistic-turn/v-1

Note --- Can Philosophical Principles be classified as "supra-empirical"*4?

*4. "Superempirical" is an adjective that means something is experienced or is experiencing something beyond empirical means. It can also mean something is transcendental or transcendent." ___Google AI overview

Note --- Are philosophical Principles and scientific Laws, immanent facts or transcendent essences? Newton's First Law of Motion versus Aristotle's Prime Mover.

*5. Metaphors we live by :

" . . . a book by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson published in 1980. The book suggests metaphor is a tool that enables people to use what they know about their direct physical and social experiences to understand more abstract things like work, time, mental activity and feelings."

Quote ---"Ideas, concepts become substances that can be measured:"

Quote ---"Most of our indirect understanding involves understanding one kind of entity or experience in terms of another kind—that is, understanding via metaphor." ___Wikipedia

*6. "In Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) state that human conceptual system is metaphorically structured and defined. According to them, conceptual metaphor is a system of metaphor that lies behind much of everyday language and forms everyday conceptual system, including most abstract concepts."

http://www.academypublication.com/issues/past/tpls/vol03/08/25.pdf

More Notes ---

#A. Human languages are based on metaphors --- figures of speech that represent the concrete material world in mental abstractions, and then express those ideas as-if they are the thing referred to.

#B. Spoken & written Words are symbols that represent my ideas in familiar terms that you can relate to. Some symbols represent physical Objects ; other symbols represent metaphysical Concepts. Concrete objects are easier to grasp. Abstract subjective feelings & understandings tend to be ambiguous.

#C. A metaphor is an attempt to express what something is "like" to me, but without making the comparison obvious. So the recipient may think I'm talking about the Object instead of the Subject. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

If a → c it does. Contraposition, flip em and switch em (reverse the order and negate both). — Count Timothy von Icarus

a → c, ¬a → ¬c does not entail ¬a -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

My question then is whether we ever utilize (B∧¬B) without conceiving of it as a kind of P. — Leontiskos

If P can only be False, yes; otherwise, no.

So do we have a proof for ((a→(b∧¬b)) → ¬a)? — Leontiskos

Uh

Leo seems to think that choosing between ρ→~μ and μ→~ρ somehow involves an act of will that is outside formal logic. He concludes that somehow reductio is invalid. His is a mistaken view. Either inference, ρ→~μ or μ→~ρ, is valid.

Indeed, the "problem" is not with reduction, but with and-elimination. And-elimination has this form

ρ^μ ⊢ρ, or ρ^μ ⊢μ. We can choose which inference to use, but both are quite valid.

We can write RAA as inferring an and-sentence, a conjunct:

ρ,μ ⊢φ^~φ⊢ (ρ→~μ) ^ (μ→~ρ)

and see that the choice is not in the reductio but in choosing between the conjuncts.

Leo is quite wrong to assert that Reductio Ad Absurdum is invalid. — Banno

I think Leontiskos is talking about choosing between the conjuncts, while Banno is correctly stating that reduction ad absurdum is formally valid.

I think the only way we can utilize logical inference is by using the modus tollens — Leontiskos

Modus tollens is p→q is True, q is False, therefore p is False. «1»

While reductio would be:

p

p→absurd/contradictory

therefore not-p «2»

So I think that a→(b∧¬b)) → ¬a can indeed be proven by modus tollens:

a→(b∧¬b)) is True, (b∧¬b)) is False, therefore a is False (from «1»).

Proving a→(b∧¬b)) → ¬a by reductio would be:

a

a→absurd/contradictory

therefore not a (from «2»)

I don't see a meaningful difference. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

I solved my main problem just right above. See if that works.

In the meanwhile, I can finally go cook with peace of mind.

(i.e. "Suppose a; a implies a contradiction; reject a") — Leontiskos

But for the record I do accept this as a valid rhetorical move. However when it comes to propositional logic, from

P1: A

P2: A→contradict

The conclusion can be whatever we want, from explosion

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=A

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=A

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=C

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=D

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=P

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=Z

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A,(A~5(B~1~3B))|=Z(P(G(F(x)))) -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

So I guess that, in order to say "A does not imply a contradiction", we would have to say instead (A→¬(B∧¬B)). From there things start to make more sense.

Since ¬(A→(B∧¬B)) does not translate to "A does not imply B and not-B". I have to fix my post above.

to:Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man. – A

A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A.

[...]

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is not a man – ¬A

¬A,¬(A→(B∧¬B)) entails ¬A.

[...]

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man – A

¬A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A. — Lionino

Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is not a man implies that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man. – A

A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A. A entails A.

Reminder that ¬(A→(B∧¬B)) is the same as (¬A→(B∧¬B))

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is not a man implies that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is not a man – ¬A

¬A,¬(A→(B∧¬B)) entails ¬A, from contradiction everything follows.

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is not a man implies that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man – A

¬A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A, from contradiction everything follows.

Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is not a man implies that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

These two premises do not entail that Elvis is not a man, because there is no contradiction. A has to entail A.

I think, keeping explosion in mind, this makes much more sense in natural language.

So let's look at the cases with (A→¬(B∧¬B)), which is finally translated properly as "A does not imply a contradiction".

Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – (A → ¬(B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man – A

A, (A → ¬(B∧ ¬B)) |= A

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – (A → ¬(B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is not a man – ¬A

¬A, (A → ¬(B∧ ¬B)) |= ¬A

Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – (A → ¬(B and ¬B))

These two do not entail that Elvis is not a man – ¬A.

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – (A → ¬(B and ¬B))

These two do not entail that Elvis is a man. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Let's see.

Elvis is a man – A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man. – A

A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A. That makes sense.

Let's say now.

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is not a man – ¬A

¬A,¬(A→(B∧¬B)) entails ¬A. That makes sense.

Elvis is not a man – ¬A

Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal – ¬(A → (B and ¬B))

Therefore Elvis is a man – A

¬A, ¬(A → (B∧ ¬B)) entails A. That doesn't make sense to me.

But I guess it does make sense when we consider that ¬(A→(B∧¬B))↔(¬A→(B∧¬B)) is valid. So, ¬A implies (B∧¬B), from where we can say A.

But if ¬A→(B∧¬B), it is a bit strange that we can derive ¬A above in the second schema. Perhaps because from a contradiction everything follows?

However, A,¬(A→(B∧¬B)) does not entail ¬A. So from {Elvis is a man} and {Elvis is a man does not imply that Elvis is both mortal and immortal}, you can't derive Elvis is not a man, because there is no contradiction being states here from where we can affirm anything.

Therefore, if ¬(A→(B∧¬B))↔(¬A→(B∧¬B)) is true, and ¬A→(B∧¬B) can be read as not-A implies a contradiction, it must be that ¬(A→(B∧¬B) cannot be read as A does not imply a contradiction. -

Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other?

Yep. Worth noting that parsing this correctly shows that the original was incomplete - implied nothing."The car is green" and "The car is red" is not a contradiction. But if we add the premise: "If the car is red then the car is not green," then the three statements together are inconsistent. That's for classical logic and for symbolic rendering for classical logic too. — TonesInDeepFreeze

More generally, parsing natural languages in formal languages, while not definitive, does occasionally provide such clarification. That's kinda why we do it.

Also worth noting that (A → B) ^ (A → ¬B), while not a contradiction, does imply one, given A:

(A → B) ∧ (A → ¬B)→(A→(B∧¬B))

So in answer to the OP

Taking "implies" as material implication, they are not contradictory but show that A implies a contradiction.Do (A implies B) and (A implies notB) contradict each other? — flannel jesus

I had the same thought when I read that. It's wellformed. It is also invalid: A∧¬AI'd like to see what formation rules you come up with. — TonesInDeepFreeze

This thread is bringing out some rather odd attitudes towards the relation between logic and natural languages. -

A Case for Analytic Idealism

Hello Fooloso4,

An engine is not an assemblage of found parts. The parts are designed and manufactured as parts of a whole. Even something as simple as a bolt cannot be understood in isolation, without it being a part of a whole.

Correct. This doesn’t negate the fact that one can explain the whole by reduction to its parts and the relationship between those parts in their proper arrangement.

A biological entity is not put together out of parts. It can be separated into parts but unlike the engine those parts did not exist prior to the living being.

Correct. Again, this doesn’t negate my point: if one is fundamentally claiming that the mind is a part (or group of parts) of a physical body which emerges due to the specific relationship between those parts, then they are thereby claiming that the mind is reducible to the body.

They are not emergent. Once again, parts are parts of some whole. The relation of parts is inherent in the design of the parts. They are designed with their function and purpose in mind.

The purpose is irrelevant for all intents and purposes here. We can likewise take a natural example with no human purpose embedded into it: take a tornado. A tornado is explained by the reduction of it to its parts (e.g., wind, dust, etc.). Now wind, dust, etc. on their own do not completely account for a tornado: the other component is how they are arranged (e.g., cold and warm wind colliding causing spiralling rotations, etc.). The fact that the parts on their own do not completely account for the tornado does not mean that we aren’t still claiming that the tornado is weakly emergent from the parts in a specific arrangement. Same thing is true for everything else, including engines.

Of course there is more that needs to be explained!

Firstly, for all intents and purposes right now, I am strictly talking about how something works when I am talking about explanations (although I do think all explanations are reductive, but that is going to derail the conversation). Physicalism is arguing that it can explain (in terms of the how it works) a mind in terms of the physical biological brain.

What is it for?

This explanation is different, but still reductive. We reduce the ‘for’ to the purpose bestow onto it by the person utilizing it or perhaps the person who created it (depending). This isn’t irreductive.

What does it do?

When I explain the relations of the parts and the parts themselves, I am thereby explaining what it does. It may not be as clear to you what it does until you watch it work, but theoretically you can figure out what it will do just by understanding the parts and the relationship the parts have to each other when the engine would be on (even if you never witness an engine on). This is only possible because it is an reductive explanation.

What is its purpose?

This is the same question as what it is for.

Either a)there are physical things that we are aware of within experience or b) there are no physical things without experience.

That is a false dilemma. As an analytic idealist, I accept both A and B. If you want to make it a true dilemma, then it would have to be:

A) There are physical things without our experience which somewhat (or completely) correspond to the physical things within our experience; or

B) There are no physical things without experience.

Your version of #A doesn’t actually claim there are mind-independent physical things, it just asserts that we experience physical things within our conscious lives: virtually no idealist is going to disagree with that.

Either a) you are a substance dualist or b) you are a monist. If b) then you cannot sidestep an explanation of how mental stuff gives rise to physical things.

This is true, and I am a monist; and, yes, I agree that I cannot sidestep the problem of how the mental stuff gives rise to physical things within conscious experience. It is a soft problem, though, because it is reconcilable in the view; whereas the hard problem of consciousness is a hard problem because physicalism is provably unable to solve it even theoretically.

Idealists mean there are physically-independent minds. Given the central importance of conscious experience in your account, what do you make of the fact that we have no conscious experience of disembodied minds?

I am not even sure what it would mean to say that one experienced a disembodied mind: I am not claiming that we have evidence of minds existing that have no bodies except for the universal mind. With the universal mind, we do have introspective experience of this.

When you have a vivid dream, let’s say you find yourself consciously experiencing walking through a park (all within a mere vivid dream while you are asleep), you falsely associate your identity with the character (of which usually resembled yourself from reality) and consciously experience the dream world from their perspective. From their perspective, the beautiful nature they are walking through (i.e., you are walking through as the conscious experiencer of the vivid dream) appears to be distinct from themselves; however, once you wake up you realize that your mind was responsible for it all: the trees, the walking path, the fellows people you conversed with, etc. were ideas in your mind and ‘your mind’ as the character perceiving it in the dream was an illusion. Your mind, as the producer of the dream, did not have a body in it. I think an analogous situation is true of reality itself: we are within the universal mind but we perceive it from our own perspectives. However, I am not claiming that there are minds other than the universal mind that can be empirically proven to exist without bodies—I haven’t seen any evidence of that.

Bob -

Kripke: Identity and Necessity

It's consistent yet violates the law of identity?

Well, if it violates the law of identity, then it is by that very fact not consistent. — Banno

Banno, consistency is a relation between the axioms or premises employed. It does not rely on the law of identity. But consistency is commonly related to non-contradiction. If the law of identity is not one of the axioms employed, then the law of of identity is irrelevant to consistency when consistency is determined strictly by non-contradiction.

Here's a tree proof:

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A=A — Banno

Ha ha, very funny. I hope you meant that as a joke.

Of course there is an actual world. It's one of the possible worlds. — Banno

You don't really believe this do you? What about the error you just pointed to, whereby possible worlds are reckoned to be an actual place? How would you reconcile these two, your claim that the actual world is one of the possible worlds, and your insistences that it is an error to think of a possible world as an actual place you might go to?

This is where Kripke shows his true colours, as a deceptive sophist. He says it's an error to think about a possible world as if it were an actual place that one could go to, yet it turns out that the only realistic way to interpret "possible worlds" is that one of them is the actual world where we live.

Kripke is anti-realist, but is trying to distance himself from anti-realism:Saul Kripke described modal realism as "totally misguided", "wrong", and "objectionable".[27] Kripke argued that possible worlds were not like distant countries out there to be discovered; rather, we stipulate what is true according to them. — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modal_realism

Notice, "we stipulate what is true according to them [the possibilities]." As I said, you are being lead firmly into anti-realism. You do not separate the representation (a logical possibility) from the actual world, as consisting of material objects with an inherent identity (by the law of identity). There is no such separation when you insist that the actual world is one of the possible worlds: https://iep.utm.edu/mod-meta/

This is the problem with Kripke's work which I pointed to already. If we accept his premises as coherent, we have only two ontological possibilities, Platonic realism, or anti-realism. If the "rigid designator" signifies a real object we have Platonic realism, because the logical possibilities are all ideas, mental fabrications, and we say that the mental fabrication is "real". But if we reject the reality of the mental fabrication, (logical possibility or possible world), then we have nothing independent of the mental fabrication, to call "the real world". The real world is just a mental fabrication, as you state here, "it's one of the possible worlds". This is firmly anti-realist, though sophistic authors will present it as a form of realism, "modal-realism", "model-dependent realism", etc..

The sophistry lies in the way that the supposed actual world is distinguished from the other possible worlds, in this anti-realist structure. To be consistent, all logical possibilities must be represented in the same way, as possibilities. The rigid designator signifies the same possible subject in each. So when you state a counterfactual such as "I might have put my slippers on. I didn't", you speak deceptively because you imply that one of the logical possibilities has a status which the other does not (what actually occurred). But you have no premise to make that conclusion. Therefore your statement is prejudiced and thereby compromised.

The issue is a logical dilemma. If one of the possible worlds is supposed to be the actual world, then we need some principles whereby we make that judgement, and decide what to believe as the truth. But if we introduce principles (premises) into this logical system whereby one logical possibility would be distinguished from the others as what is actually the case, that would give this one a status which the others do not have, rendering it as other than an equal possibility.

That's why we ought to reject Kripke's principles altogether. If every logical possibility is equally possible, as indicated by the definition of "rigid designator", and one of the possibilities is supposed to be the actual world, rather than a representation of the actual world, we have no real principles for judging the truth. -

Kripke: Identity and Necessity

Yes, it's consistent because they violate the law of identity, as I described. — Metaphysician Undercover

It's consistent yet violates the law of identity?

Well, if it violates the law of identity, then it is by that very fact not consistent. But we know it is consistent; hence, it cannot violate the law of identity. As noted earlier,

My bolding.Quantified Modal Logic—which combines individual quantifiers and modal... is sound and complete with respect to constant domain semantics, in which each possible world has precisely the same set of individuals in its domain. — SEP

Here's a tree proof:The law of identity is not valid. If you think it is, then show the logic which proves it. — Metaphysician Undercover

https://www.umsu.de/trees/#A=A

The remainder of that post is... increasingly odd. It shows again the error Kripk point to here:

and here, again:It is as if a 'possible world' were like a foreign country, or distant planet way out there. — p.174

Of course there is an actual world. It's one of the possible worlds.There is no actual world, so how do you propose that I decide which of the possibilities to believe as the truth? — Metaphysician Undercover

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum