-

A new home for TPFThe one thing I'm concerned about transitioning to another platform is that this website will just deteriorate over time without maintenance and the whole archive will be lost, something that's been happening to the rest of the internet with broken sourced hyperlinks everywhere. — Saphsin

This website, the one we're on right now, will not deteriorate---it will be completely closed early next year. The content, however, will live on, hosted by me on a static website (tpfarchive.com), which is read-only. I will maintain this indefinitely (though it won't need much maintenance).

If you have a better plan to preserve the archive, let me know. Maybe you want to put up the money to make a physical book? -

A new home for TPF

Thanks Bret!

Looking at the last page of those discussion results, it seems The Philosophy Forum has been around for just over 10 years, or since October 20th of 2015. That's curious and wonderful the website is a decade old. — Bret Bernhoft

TPF: Curious and wonderful since 2015.

In fact, this site is a kind of continuation of forums.philosophyforums.com, which started probably in the early 2000s but collapsed around the time when this one started. -

A new home for TPF

:up:

It's a little too slow from where I am. Maybe I'll paginate the results on the "your posts" page (you can get them all in a single file in the download). -

A new home for TPFBut you can have a look at the archive site, built on a data export from a few days ago.

https://tpfarchive.com -

A new home for TPFI had the temporary URL of the new site showing here for a moment there but I was forgetting that since the legal stuff isn't in place I can't approve any new members yet.

-

Do you think RFK is far worse than Trump?How do you mean? — Christoffer

I meant that I'm not on board with your rhetoric. Anyway I only came in here to shed some light on the political leanings of TPF. In any case, the conservatives on the staff are no more ignorant of the facts than the others, as far as I can see. Facts have nothing to do with it, and in general the accusation that the other side ignores the facts is thrown from both sides. It's a nothing argument, on its own. -

Do you think RFK is far worse than Trump?Yet, there's also a point to be made that many arguments that rely on facts tend to be called leftist. There's far more climate science deniers or general deniers of scientific results on the conservative right... so if a human's best attempt to reach a truth based on facts and scientific data is considered "leftist", then I guess that tells more about the political spectrum than that this forum is "unbalanced". — Christoffer

I don't agree with any of this, and I'm very left. -

Do you think RFK is far worse than Trump?

On the staff we have between 2 and 2.5 Marxists, 2 left-liberals, and 2 conservatives. I guess that's more left than right. -

A new home for TPF

Why is it better for me to turn it off globally than for you to ignore it?

I can think of reasonable answers to that—I just want to understand the opposition. -

A new home for TPF

As for downloading, you can just do Ctrl+p and then save as PDF. This will work on the new site (you can try it here on another Discourse forum) and also on the archive site. -

A new home for TPF

It sounds like you're talking about ongoing discussions, but all the discussions on the archive site will be finished, static, frozen in time. So I'm confused about what you're looking for. You can't "enter the fray" on the archive site.

As it happens I built a first version of the archive site yesterday and the way it works is it shows the full discussion on one page.

The new site doesn't have pagination at all. Every discussion will be infinite scroll. There's an AI "Summarize this topic" button too, but I haven't tried it, and it can be turned off. -

A new home for TPF

The archive will exist as a website, where you will be able to see all the discussions and posts. It will have some kind of search functionality, and it will have a "Your posts" page where you can view and download your posts (or anybody else's: you'll just enter the username). You'll be able to access that download while you're offline, if you keep it on your device (obviously).

If you need to access everything offline, and not just your own posts...well, it's possible for me to provide a package you can run locally, like a private website, but I find myself wondering why you would need to. -

A new home for TPFSince the old site will be preserved, I wonder if the "advanced search" functions that work now will work there — Paine

The content will be preserved but it won't look or work like the existing site. It depends how much time I spend on building it. Searching by author or discussion title are easy enough — not sure about a full text search. -

A new home for TPFThanks Jamal, the projected new forum sounds great. Is there any way of exporting one's posts from the old forum as a word file? — Janus

I'll have all the data and I'll be able to provide members with a posts export on request. In fact I might provide it at the archive site. -

A quandary: How do we know there isn’t anything beyond our reality?

-

An Autopsy of the Enlightenment.Mind in Life — Wayfarer

Sent me to sleep, that one. I may try again one day. -

An Autopsy of the Enlightenment.reason is just a tool — Tom Storm

As Wayfarer might be about to point out, this is the problematic Enlightenment notion of reason which is in question. -

A new home for TPFOn the other hand, could you tell me if there will be a way to fine-tune the settings to hide topics I don't want to see (in case I want to create an echo chamber and not know what people think about certain things?) — Astorre

Yes, on the new platform you'll be able to mute topics and whole categories, so that they don't appear on the /latest page.

I also wanted to suggest, if appropriate, adding more sections—for example, metaepistemology or axiology—so that I could narrow my choices a bit more — Astorre

We can always make subcategories but I don't think those ones would be used enough to merit that. -

A new home for TPFI also thought the layout from the old site was better in certain ways (although it had countless bugs and unreliability problems) because it showed the categories and the posts by recency by each category and not just everything at once. What happens under our current system is that if 10 people come up with new religion posts (for example), the main board is overwhelmed with that and it looks like that's the ony thing being discussed. If posts are divided by category, that doesn't happen because you can just not pay attention to those categories you're not interested in. I don't know if the new software addresses that or not though. — Hanover

I've made the home page of the new site show topics from all categories ordered by most recent, just like here. But unlike here, if you go to the "All categories" page the categories are ordered by most recent—so that page would fit what you'd like to see as the home page (Philosophy of Religion would show at the top but wouldn't overwhelm the page). Personally I wouldn't want that as the home page. Maybe I'll do a poll.

On the old site I always went to /latest or whatever it was, which was the same as our home page here.

Anyway in Discourse it's all configurable. -

A new home for TPFHad some problem receiving emails from this site when changing passwords. If the move over to the new site requires an email invite for the current account, what happens if it fails? — Christoffer

It won't be invitation-only and you'll be able to just go to the site and sign up yourself. I'll be making an announcement when it's open for new sign-ups. As I say, around March.

Wouldn't there be an email list for all current members? So that taking that list into approved members for the new site will work and when signing up the email is already registered on an approved list there.

Meaning, using the email you registered on this site will let you into the door of the new site when registering. — Christoffer

It's essential that all users of the new site have read and explicitly agreed to the new Acceptable Use Policy. New users confirm that when they sign up. So there won't be any pre-approved accounts.

Also, what happens to stuff hidden on this site from people not logged in? Like the short stories? If there's stuff like that disappearing from view, maybe that should be moved over to the new site? — Christoffer

Since I have to write some code that turns the existing site into a static site (based on the data export), I can make everything visible (obviously not private messages).

EDIT: Actually you'll need to verify your email when you sign up. If emails from infoatthephilosophyforumdotcom are not reaching you, that will be an issue. -

A new home for TPF

Even if they're on old-fashioned software I think we should celebrate the continuing existence of independent discussion forums. Not everyone wants to discuss everything on Reddit. -

A new home for TPF

Yes, I had a look at that when I was researching NodeBB. To be fair—and because I'm reflexively argumentative—dull isn't necessarily bad for a forum, and NodeBB can be customized extensively. What matters more to me is how smoothly everything works. Discourse in my opinion just runs better, always looks nicer due to better all-round design and compatibility of themes and colour schemes, and setup is less of a struggle. -

A new home for TPFIt sounds like there is not anything our current software can do that the new software cannot do. If that's correct, then we can not only fully replicate what we had, but we can also add to it.

I say this in response to Outlander, who is concerned that the Shoutbox as we know it will necessarily disappear with the introduction of a live chatbox. I would think (or suggest) that if there were a desire to start a thread that was lounge-like and not chat-like, that could be done?

If the two turned out the same, there'd be no need for both, but if there were an important difference, maybe have both, but that to be determined as we go along. — Hanover

Well, I'm planning on having a Lounge at the new place too, although I want it to be different:

NOTE: This is not final. It's also a bit confusing because it says "chat," and there's already live chat for that.

Otherwise, I'd like to know precisely what "lounge-like and not chat-like" means. For example, some people might not like chat because the textbox is so small: they might want a large box to compose a wee story with multiple paragraphs. They might be unaware that you can do paragraphs in chat using shift+return. In Discourse the textbox gets bigger when you do that. It never gets as big as the composer in the long-form discussions, but big enough for most Shoutbox posts, I would think.

Anyway, the community will decide. If a long-form discussion in the Lounge turns into an effective Shoutbox I might consider letting that continue. But I'm heavily into turning the Shoutbox into a chatroom so I'll resist such developments. -

A new home for TPF

:cool: :up:

During the transition, is keeping the email info current critical to rolling over to a new account? I have just have been relying on messages once signed in to communicate. — Paine

You can use a new email address at the new site, and you can change your email address here as well if you like. -

A new home for TPFOut of curiosity, why did you opt out of your former idea of going with Communiteq hosting? — Leontiskos

Fair question.

I'm sure Communiteq is good but I think we're better off long-term with Discourse.org . My strategy is to go with the official premium product and see if we can afford it—we can always move to Communiteq or self-hosted later on if it proves to be too much. But I don't see why we couldn't cover $100/month. We've just been too relaxed about subscriptions—if we'd made a bigger deal about it I'm sure we could have got more members to subscribe.

This is a serious website and we want it to keep going for a long time. It deserves the real thing, not just a cheaper third party alternative. I realize this might seem shallow or impressionistic but I think it's significant nonetheless. Discourse.org seems like the professional option.

On Discourse.org we're dealing with the people who develop the software. They know what they are doing. Updates and plugin compatibility and what-have-you are handled by those who know the code most intimately. Support is fast and definitive, and the service is extrememely reliable.

It also has better performance due to differences in their server infrastructure, apparently.

Incidentally, I tried NodeBB for a couple of weeks and XenForo for a couple of days, and some other more Enterprisey things like circle.so . I was almost ready to go with NodeBB but then I tried Discourse again and the experience was substantially better than NodeBB.

Also, ↪regarding

"form and content in philosophy," I would suggest "zen mode reading" (and not just composing), where one can devote their entire screen to the topic at hand (example). Although I think Discourse allows this modification on a user level by default...? — Leontiskos

I can't see this functionality anywhere but I just tried the Firefox reader-view and it worked fine, so I presume other browsers can achieve the same thing. Anyway look:

When the sidebar is collapsed it's pretty distraction-free, no?

It's also worth noting that once web pages and forums became asynchronous the distinction between live vs. non-live chat was largely superseded. Older forum software which was not asynchronous (and required a page re-load after submitting a post or PM) is now gone. It was that page load that made it feel "non-live." Of course, that model was nice insofar as it felt more "long form" (like sending a letter), but the current Shoutbox is this weird amalgam between short-form and long-form media. An instant message style UI would simply be better for the TPF Shoutbox (although the non-paginated Discourse format is already more "live" than a paginated format). It would also help discourage short-form bleed into the main forum. — Leontiskos

Yes, good points. The difference is partly in how the functionality is presented: in the long-form discussion, the big serious composer window is obviously for long posts, whereas it's just a small bare-bones textbox in live chat. Also we can implement minimum post length in the discussions.

Relatedly, I would propose time limits on editing. The perpetual editing of TPF leads to careless composition, in my opinion. — Leontiskos

Yes, I'll be looking into that. I might make it subsciber-based. I'm pretty sure it can be implemented in Discourse anyway.

You can, but the search is wonky. It isn't thread-indexed, but rather functions via a search on common words in the thread title. So it will return results for any thread with similar titles. There are other problems too, such as the fact that threads containing special characters are unsearchable, and users with special name formats are not present in the mentions dropdown. — Leontiskos

Yeah, the search here is seriously defective. -

A new home for TPFIn my experience a traditional Shoutbox or "live chat" is generally at the very top of the forum index (though this can—usually—be altered and even "collapsed" or outright hidden per user preference) and is roughly 5 - 10 lines of text "tall". Though it can be scrolled up. This discourages all but simple pleasantries and spontaneous "what's everybody up to" or perhaps the occasional "thoughts on today's topic of XYZ?", which is wholly sufficient, sure.. — Outlander

See the above. Chatrooms can be expanded to fill the main page panel.

As it is now, sometimes the Shoutbox takes a few days to reach a new page (10 replies), sometimes it creates more than one page in 15 minutes. From my experience live chat permanently truncates a certain number of older replies based on however many new replies are made. It's nice to be able to go back and see what was said a day or two ago. — Outlander

We can configure this. Right now I've got it saving the chat messages forever. -

A new home for TPF

I actually only just realized that you can search within a discussion here on PlushForums, I mean without going to the Advanced Options page. Doh! -

A new home for TPFThere are three Jamals. That's enough. — javi2541997

Yeah :grin:

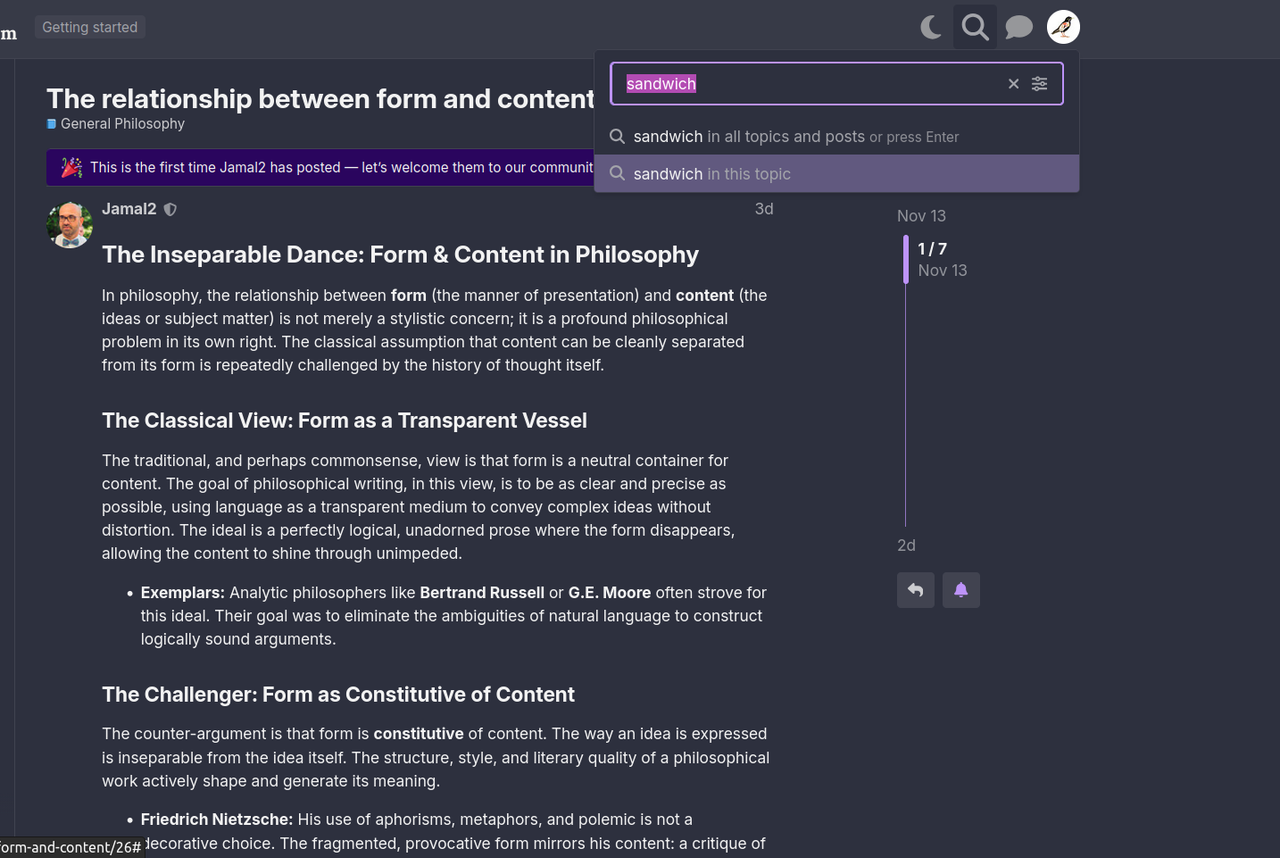

Perhaps—another different feature I am thinking of—each thread would not be ordered with pages, as in PlushForums, but just a single page where all the comments and replies are posted. Then, if I wanted to reread a response from you, I would have to scroll until I found it; not go to page 261 as we do here. — javi2541997

Yep, no paging, either in chat or in regular discussions. But there are other ways of navigating within a discussion, and you can easily search within it too (for chat as well):

-

A new home for TPF:up:

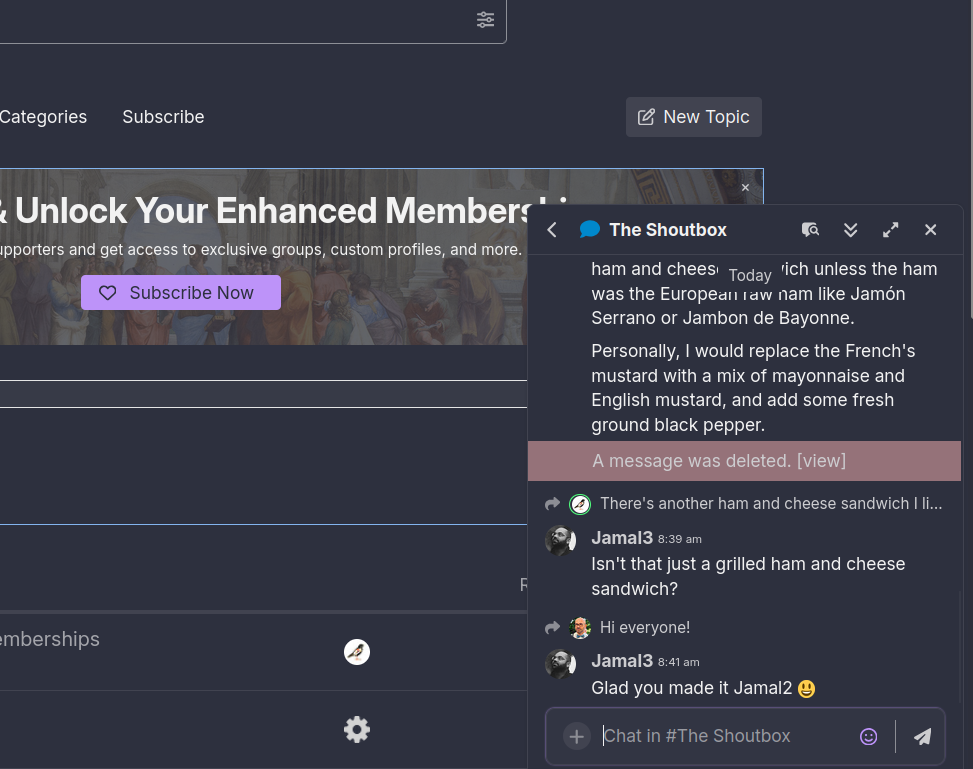

The Shoutbox won't be the same, but in my opinion it won't be worse. It never really belonged among the discussions, and this has caused problems.

Here are some screenshots of the Shoutbox, one expanded and one floating in the bottom right corner.

As you can see, it's pretty lonely there at the moment. -

A new home for TPFYou're probably right. But even what's his name likes the idea of a "community posting room", likely for the reasons I've suggested. — Outlander

I don't get it. How could a live chat not function as a "community posting room"? Granted, I don't really know what it means. -

A new home for TPF

I want the sites to be separate so I'll transfer thephilosophyforum.com to the new site and use something else for the archive. -

A new home for TPF

The number of posts will be visible on the user's profile, but not within discussions.

Incidentally, aside from the number of posts we will have other things like badges, trust levels, and upvotes, though I'm not sure how we'll use them yet. -

A new home for TPFUnderstood. I appreciate that you will keep the site as a read-only archive. There are many memories here, and it would be a pity to lose them forever. — javi2541997

Indeed :up:

I guess we have to wait until you set up the new TPF to create our profiles in this new software, right? — javi2541997

Well, I've made progress in setting it up already, but unfortunately I can't open it up until everything is sorted out legally, I have a business bank account connected to the subscription system, and stuff like that.

I'm in. I hereby agree to the costs, investment and other features to keep things going. — javi2541997

Thank you for the support Javi. :up:

Jamal

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum