-

What counts as listening?Well, all. Please forgive the meandering. Thanks for the input so far, it's helping me to at least express something and not just get stuck in an intuitive yet unspoken rut.

Did you find the article on his aesthetics, specifically? — bongo fury

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/goodman-aesthetics/

Sure, but for me the crucial insight is that musical artworks are sound-events: or, usually, sets or classes of sound-events, identified either through notation or recording or both. — bongo fury

Let's go along with this. The identity of a musical artwork is a set or class of sound-events identified through notation, recording, or both. This will allow us to differentiate between the work of art and our appreciation of the work of art, or as @Outlander put it :

Often people differentiate between hearing and listening. — Outlander

So we could say, in the above that we heard the entire peice, at least. And avoid something along the lines of @jamalrob asserting that we never hear the entire peice, which seems pretty absurd too.

I've never experienced a musical piece aired on TV being interrupted by ads. Maybe they're too short or maybe the producers intuit that any interruption to a piece of music amounts to altering it. :chin: — TheMadFool

You know YouTube has the audacity to intersperse ads into long orchestral recordings? Heathens, I tell you.

I like how you point out that when we push pause we're introducing something to our experience which the composer also uses in the artwork. That would be why the visual division served as analogue -- because the artist uses space in the case of paintings.

Still, I think I'm being won over by the identity theory posited by @bongo fury, for now at least. Whereas pausing it does introduce a significant difference to the work of art, the identity of the work of art is unchanged by my pausing it and starting it back up again.

Yeah, you heard the entire piece but not in one setting, so it's different if you heard it in one setting. It's probably an irrelevant distinction, but I suspect if you took 800 breaks so that it was so disjointed and so much time elapsed that you couldn't formulate it as a single piece in your head, it'd be relevant.

It's like if I watched the entire Game of Thrones over a few days versus if I watched 20 seconds a week for several years and then declared I had seen the whole thing.

I knew a guy who told me he hiked the entire Appalachian trail, which seemed less impressive when he explained he had done it over the course of many years, taking a different section each time. It was still a feat, but much less than someone who set out for many months and finished without a break. — Hanover

I think this gets along with what @bongo fury is saying. We hear the entire peice in any instance, but our aesthetic appreciation -- or the impressiveness of the hike, in the other case you mention -- *can* differ depending on how broken up it is.

What if you didn't hear the entire piece, and yet you loved it, you were able to analyze it and understand it and be inspired by it and other good things? I'd say in that case that you did appreciate the piece aesthetically. — jamalrob

I think I am inclined to agree, now, against my former intuitions. I think the distinction between our aesthetic appreciation and the identity of the artwork is useful here. While there is something to be said about listening to the whole thing with that intention, or even in being absorbed in a work of art -- like what you mention about dance being just as good an example for absorption -- it probably shouldn't define the identity of the work of art, or be some sort of necessary condition for aesthetic appreciation.

Taking this to its natural conclusion: we never listen to the entire piece. What then? — jamalrob

Decide whether the question is about whether or not we have encountered a complete and genuine instance of the artwork, or is instead one of any number of related questions about our processing of and response to whatever it is we have actually encountered. — bongo fury

I think, given the eventual focus on listening, I like the idea of deciding that we have heard a genuine instance of teh artwork, but that the identity of the artwork differs from our appreciation of the artwork. So, define the stimulus as such-and-such to explore our response and processing of the stimulus.

I'll tell you what I was more interested in for this topic...

I listen to a song once, it leaves a different imprint than twice, but the second time makes a pattern, subsequently third and fouth are different but still make a pattern, and then a different pattern emerges in tries 5 - 8, after that a pattern is possible but it's not as strict as 1-8.

1. The First Imprint.

2. (with partial memory)The Imperfect Judge.

3. (with a semi good memory)The Crossing.

4. (with good memory)The Perfect Judge.

Without going on to 8, I just want to highlight again that the 2nd listen is a different resound than the 1st and subsequently 3-8, and there's a rather strange pattern to it.

I have called this previously, mathematically, a nexus but I won't build on that just yet.

Any clue what I'm on about? Anyone? — ztaziz

I agree that the 2nd time I listen to something it's a different experience from the first time. Even more than that -- the more I listen to a particular genre the more I'll hear on a first listen of songs in the same genre, or sometimes even just having more conceptual tools will enhance my ability to pick out different meolodies, instruments, or harmonies as I listen.

Something that really surprised me when I first got into classical music was this phenomena -- the more I read about classical music, the more I heard when listening to both well-worn musical pieces and new ones that I hadn't heard before. There was a definite conceptual element to my direct hearing of the music, at least in producing my experience of the work of art.

And I think this iteration continues on. Some works of art can be listened to so many times that it goes on even greater than 8, and is probably relative to both the listener and the work of art.

And each listen seems a little different from the previous, I'll agree. -

What counts as listening?I guess I don't understand the significance of the question to you. So I'll offer a deflationary response.

If it is required to hear the entire thing in one go to count as listening, you didn't listen.

If it isn't required, you did.

I can see a few intuitions regarding continuity of the piece in the background, but I dunno how they relate. — fdrake

The obvious question is: why is this important? — jamalrob

Still wanting to loop back around to @TheMadFool, and also more of what you post @jamalrob -- but it's taking me more time to formulate thoughts there so I wanted to quickly address the question of significance.

First, this is more of an errant thought on my part -- a musing. Maybe it'll go nowhere, maybe it'll just trip me off into something that's already well explored that I just hadn't thought of before, and maybe it'll come up with something interesting.

Second, the concept of listening is something that I think is pretty well unexplored and directly relates to quietism. Further, aesthetics is one of those areas that I think is pretty awesome for philosophy -- it's not as trapped by all the intuitions about truth and knowledge and seems to be able to work more freely because of this. So there are some other interests that pursing this question relates to, but it's also just kind of interesting unto itself.

But, again, I want to emphasize that this is very much in errant thought territory, and not well-thought out or historically grounded or anything like that. Just something interesting to think through and about, if it happens to grab you. -

What counts as listening?

Still by far my favorite things to come from the internet is the wealth of references I never would have stumbled upon on my own, or would have done so at much slower speeds. I took a peak at the SEP Nelson Goodman article, and started to read the entry on identity, but this in turn went back further into the article. So I thought, before just reading the whole thing, I'd at least ask if I was on the right track in finding this bit on print-making and photography?

Not that it's necessary for me to read it all before responding. I'm more collecting there. In response:

It's interesting to me to think of music in these two different categories - the notational vs recorded (or perhaps even live as another category? Jazz improv without recording comes to mind)

In a way it's like we're trying to match something. Not that there can't be small differences -- such as the small differences between different conductors or musicians when playing from the same score. You mention this -- it's a matching that doesn't have to be exact, it just has to fall within some limits. Limits that are likely imposed by the listener, to an extent -- someone who has an ear for a particular orchestra or conductor likely has more narrow limits to someone who is just passingly familiar with some orchestral work.

With recorded music I don't know if matching is as easy. What makes a "small" difference? A few pops at the beginning of the recording that weren't there in the master don't seem to make much of a difference. We begin listening when the instruments begin, not in the dead space around the recording.

Hrm hrm. Still more errant thoughts on my part, I'm afraid. -

What counts as listening?Oh, OK!

I may have misread @TheMadFool then, or just read him into your response too. My mistake.

I guess I'd say that you did not hear the entire peice then, and for some reason I read you as saying you had -- but you stated that the listener heard something different from the original score. OK.

This makes common sense to me when I look at examples.

But I wonder if there's some conceptual dimension here -- like, is there something that spells out what a complete work is? When do you stop listening? And what are these levels of commitment to listening? To what extent is the listener a part of the listened (for a work of art, at least)?

That sort of thing.

And I find it hard to give much of an answer, but it's something I'm thinking about -- hence the thread, to see if others have thoughts on the same matter. -

What counts as listening?

This was the piece of music I was listening to when I formulated the question. It's something that really only works when taken as a whole. Other examples would be movements in a symphony or even very pronounced melodies within symphonies -- like Beethoven's 5th and 9th, which have very distinct and remembered melodies that everyone recognizes, but which require at least many different parts to be heard in full. -

What counts as listening?

Let's try it like this.

*

*

***

*****

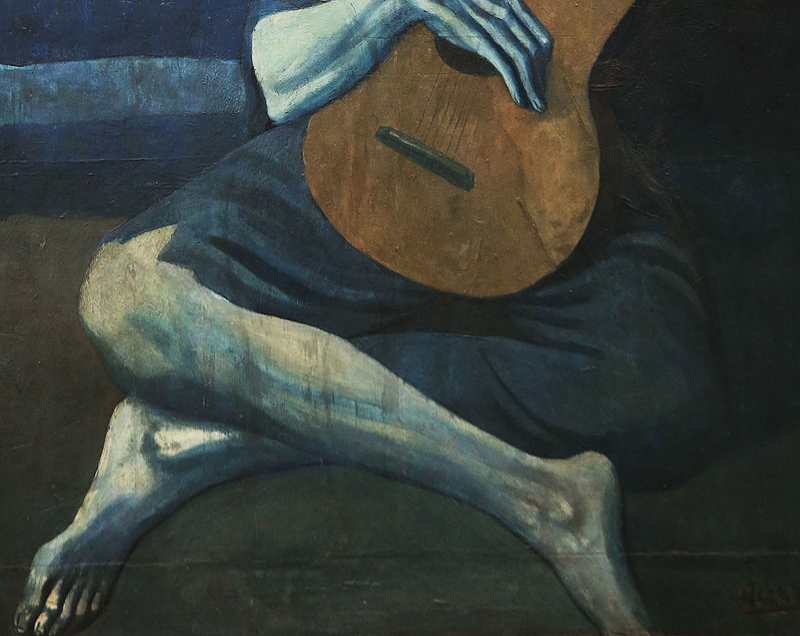

We have here two parts of the old guitarist. Together as a whole:

Now, by your reckoning, all we would need are the first two images and we could say we have seen the old guitarist. Break it up however you might imagine, too -- we can imagine it broken into hundreds of squares and triangles by some randomization algorithm, and by your reasoning if we have seen each of the hundreds of pieces then we have seen the entire painting. Hopefully you'll excuse me for not carrying out the demonstration, and you're able to see why someone would object to that.

We need to see the whole painting. Sometimes we need to see the entire painting hanging on a wall, and not just pictures of them on the internet, to get the whole effect. To stay with Picasso, Guernica is very much like that: its size has an effect on the viewer which is missed in looking up images of it.

I'd like to posit, at least, that the same holds for music. I can put music on in the background and hear it while focusing on something else, I can pause it and then go to work and come back hours later and restart where I was at. But there is also something to be said for listening to the entire work in a single session while concentrating on it. And I don't think the analogy is perfect -- I think there really is a difference between the visual and the audible, in terms of art. But it's close enough to hopefully highlight that there is something about continued listening which is important in evaluating music. -

Metaphilosophy: Historic PhasesI, for one, am very appreciative of historical methods. You've given me a lot of good thoughts to chew on @Snakes Alive, and for that I am appreciative -- especially in times such as these where I have time, and find myself continually returning to philosophical quietism in my own loop of thoughts.

In the interest of the historical method I decided to look up whatever happened to be published in Nous. I'm not sure where to get a copy of the article, but they at least post abstracts. Two abstracts popped out for me.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nous.12259

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nous.12272

In the first we have some of the tools you identify as philosophy. And we also have useage of other concepts. A lot of philosophy of science, and related, is like this in my experience. So, for instance, we have the author asking after an analysis of biological function -- which is a conceptual request on a discipline. What is wanted is the form you posit -- "What is X?" -- however we can arrive at some concept and have it be productive. We can, of course, say what is productive is definitionally not philosophy. But then I'd say we're not staying true to our historical roots -- we have an artifact of philosophy, a philosophy journal, and what we see are the use of classical tools being put to use.

The second link is an example of what I'd say is something of the normative dimension of philosophy that your account misses. Even Plato had normative concerns. One can even fairly read his ouevre in that vain -- that the death of his teacher at the hands of sophists was the monumental injustice that spurred on his philosophy, and that all other concerns are tertiary to his desire for justice in the world. I thought of bringing up late antiquity to highlight this too, as they emphasize this element much more strongly, but the concern is right there in Plato. Which isn't to say your account his wrong, here, since this is actually a through-line back to Plato -- but that drive for knowledge of what is good is a major part of a lot of philosophy, and is missing from your account. It is, in part, a kind of literature dedicated to wisdom.

Second, and others have noted this too, I'd say that as interesting as your account is it might be more local than you're putting out, and that philosophy -- while it may not follow the usual lines put forward -- may also have a more general impulse. I'd say that I'm inclined to think in this direction, simply because philosophy as arisen in other parts of the world other than Greece. So, like money, religion, art, and politics philosophy comes about seemingly spontaneously, and this is even confirmed in everyday sorts of conversations on philosophical topics -- such as "how do you know?", "Do we have freewill?", or "Does God exist and what is he like?". There's one particular story and pseudo-lineage we call Western Philosophy that draws from Greece, and it likely picked up, along with that influence, the blind-spots from which that tradition draws -- in your thesis, the litigious aspect of ancient Athens. And it would be a very interesting historical exercise to see in what sorts of conditions philosophy finds itself -- does it find itself in similar circumstances, where argument in court is given such importance, and then these same language-games then get applied more generally to other subjects? Or does it arise in times of despair, such as when Plato despaired humanity? Or is it merely the mark of powerful and great civilizations, employing artisans and priests and philosophers to demonstrate their superior civilization, thereby giving them empirical proof of their right to conquest?

Third -- I'd hesitate a little in putting too much stock into historical methods. Not because I don't prefer them. I do. But because they also end in aporia! :D The same with art. The same with religion. The answers are ambiguous and always will be, in these disciplines. Yet, somehow, they mutate and become something different along the way, they add on new creations while assimilating the old. -

Analytic PhilosophyYeah. I have some drafts thus far, but that's the kind of thing I'm actually focusing on right now with occassionally looking up sources to see where the previous authors came from. But for the most part I'm just trying to improve the brass tacks writing of the thing! :D

-

Analytic PhilosophyDooo eeeeet.

One thing I think I'd stand by is saying that while rigor and clarity are defining features of analytic philosophy -- even values commonly agreed upon -- that doesn't mean that these values are exclusively analytical, just definitive for analytic philosophers.

The page is kinda a spaghetti mess and I'm trying to untangle it bit-by-bit as I go about all my things in life, but I was going with the approach that analytic philosophy can be characterized without reference to other traditions since I don't think there's a good distinction to be made between the usual suspects -- i.e. continental or existential, etc. -

Analytic Philosophy

well -- here's an attempt at replacing the whole first paragraph into something succinct. Then move the bullet points down below to different features, maybe. Tried to cut out the compare/contrast type stuff because I generally don't think there's a distinction to be made between analytic/continental/existential/marxist/whatever. They're just historical categories.

I signed up for an account to edit, but the editing portal was... intimidating. lol

Analytic philosophy is a tradition of philosophy that began around the turn of the 20th century and continues to today. Like any philosophical tradition it includes many conflicting thinkers in a broad umbrella with its own particular lineage and history and so is resistant to a clean-cut summary. Some aspects generally found are a fascination with modern scientific practices, an attempt to focus philosophical reflection on smaller problems that lead to answers to bigger questions, and valuing clarity and rigor in one's philosophical thoughts and arguments. -

An hypothesis is falsifiable if some observation might show it to be false.I can't think of another way to say it that's any different from the wiki.

-

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeStill mulling over the significance of Davidson's rejection of conceptual schemes. I'd be interested to hear some new thoughts on the questions below:

If the essence of a conceptual scheme can be located in a far-ranging belief, are we back to square one? Back to an essentially (although a belief- rather than a concept-based) relativistic picture?

What is the significance of the rejection of conceptual schemes if our beliefs continue to paint a picture of fundamentally different ontologies (and sister -ologies)?

Belief seems just as potent in creating a kind of weltanschauung-relativism. Different people believe the world fits best into such and such a belief system. Not such a far cry from conceptual relativism. Maybe someone can clarify the distinction. — ZzzoneiroCosm

I guess it depends. We could just get by by saying that even if they believe such and such, and there are different meanings to the beliefs, that they could also just be false beliefs, or they could be the sorts of statements that are only apparently truth-apt because of their form but are not truth-apt because of their content. Maybe other ways too. Also it depends on what we mean by fundamental difference, as opposed to just difference.

IIRC you referred to a difference between physicalism vs. idealism as examples of fundamental difference. I guess from my perspective I don't think either thesis really gives us much to go off of, at least in the general statements of such. What exactly is being argued over? What is being said in saying "Everything that exists is composed of physical/mental substance"? Well it depends on the individual stating as much. For a philosopher the meaning is embedded usually in a pretty intricate series of inferences are reasons that begin to give shape to the statement that makes it something almost unique unto itself -- it has a new meaning that the original sentence I put on display doesn't elucidate, and usually that meaning is critical. In more popular discussions usually what is at stake is the truth of some other belief like "God exists" or "There are objectively good acts" and so on -- things which are similarly problematic and not easy to describe or assume, as long as study philosophy. Sort of like the original statement.

So given that these things are not clear, or at least problematic, I have trouble believing that they are fundamentally different and true, and so I have trouble believing that the mere existence of these beliefs makes truth relative to them or something along those lines. It would depend on the details of a given position. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeCool.

My apologies for being slow in replying.

So then I think, to focus my first reply here -- which is directed at partial untranslatability -- I'd say that we could learn two different paradigms (to keep Kuhn in sites) by using them. And then this would be how we'd be able to tell that the two different paradigms do not have the same meaning.

So here, I think we can say, language is presumed as you note. It was only on the topic of total untranslatability that a criteria for languagehood was sought after -- which has some interesting implications, I think, like when you were talking about understanding dolphins and other alien intelligences. But I think I'm going after making sense of paradigms, here -- or making nonsense of them too, if that be the case.

So when I ask what more someone could want -- well, they could want as faithful a rendition of the meaning as possible, and recognition that the meaning is not exactly the same. We want someone to recognize that there is value to the statement in its original language, that the resonances of meaning are lost in translation, that there is something valuable in not just translating one language into another but in learning the language from which some work of science or art comes from.

I think that for paradigms to work, though, I would have to go a step further. As you note this is about a comparison between words -- from words to words, meanings to meanings, and not from words and meanings to world. It would seem that in order to argue in favor of paradigmatic change in the interesting sense Davidson is talking about here (and not just in a sociological sense as we can also take Kuhn to be talking about) that not only would meanings have to differ, but the relationship between the world would have to be one of truth.

And that's the kicker. Is what is lost in translation not just the resonances of meaning, but also truth? And that's a somewhat cryptic phrasing -- maybe it's cleaner to say are there languages where some sentences cannot be translated into one another, but truth is retained in both instances? Which actually differs, a bit, from merely contradiction. It's not like there's a proposition P and ~P, one of which is expressible in one language and one of which is expressible in another where they are both true but cannot be translated between each language, but P is only expressible in L1, and ~P is only expressible in L2. We might call that a version of hard paradigms. But all that would be required is that there is some sentence in a language that cannot be expressed in another language, and it also is true -- a sort of soft version of paradigms. So there's a proposition P which is expressible in L1, is true, and is not expressible in L2

And while it may be too early to tell at present it seems that we have reason to believe that the differences between quantum mechanics and relativity give us some example of this smaller, partially untranslatable, and soft paradigm (here I have in mind their different characterizations of causality -- which, in spite of various attempts to make QM deterministic, the actual usage of causality in practice is stochastic and so I'd say we're safe in inferring a difference, even if we want to put that difference in different ways that harmonize more than not). How do we understand the two? Well, we use them in their respective contexts -- we learn their meanings. We then compare them and see that there are some sentences in one that are not translatable to the other, but are also true. Some people work on trying to bridge these two theories, but it is enough for my point that right now we do not have such a bridge. They could, after all, both be true in their respective ways. Perhaps the true sentences in one are just better equipped to deal with certain phenomena in certain contexts -- hence why one isn't expressible in terms of the other. They really do just mean different things and are useful in those respects because they are fine-tuned technical languages built for that express purpose, rather than to serve as a universal-sort of language of the universe.

Anytime we delve into specifics there's a host of interpretive difficulties that would take longer than a paragraph to go through, and may in fact just be distracting to our overall argument. Hopefully I've elucidated how we might understand a paradigm, at least, even if you disagree with the example -- the hard/soft version of paradigms, with a focus more on the soft because that's the easier one to defend, and really it's all that's required. Meaning may be ineffable, but surely we can at least recognize a difference in meaning in spite of not having a theory of meaning? And if that be the case then we should be able to point to examples of sentences which cannot be translated into at least one other language, and are true. And if that be the case then all that I might ask, at least, is for our translator to recognize that difference. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeI'm concerned about criticizing the article correctly, hence my defense of it. But I suppose what gets me is this, @Banno -- how do we learn our first language? Surely we don't translate back into some more primitive language through the T-sentence, or some formulation like that. Obviously we wouldn't do it explicitly, but we could claim implicitly that it's so -- but then we'd have to have some proto-language or something going on to allow that to be the case.

I'd submit that there's a far simpler explanation -- that we learn the meaning of a language through using it. But if that be the case then the T-sentence provides a hopping-over point for learning some phrases within another language through the "...is true" predicate -- but there comes a time in learning another language that we simply know how to use said language.

If that be the case then we can come to know two separate languages with partially different meanings. And we know they have partially different meanings not because we translated back to our native tongue, but because we learned this new language in the same way we learned our first language.

That is: rather than translating, all we do is compare meanings.

And in the same way that we can compare meanings in two distinct languages we could also compare meanings in two different conceptual schemes. No? So the way a person would know, ala Kuhn, that two paradigms are different in meaning is they bothered to spend the time to learn the meanings of the different paradigms.

And while we could understand them both, just as we can understand two languages, we didn't understand them through translating back into our native language -- but by becoming familiar with the meanings of the beliefs related (or concepts? Not sure I even require "concepts", i.e., I could follow your suggestion that we replace concepts with beliefs and I think this line of thinking would hold).

And this is how we'd come to make an understanding of partial non-translatability -- through knowledge of two distinct languages with different meanings.

Now one thing I'll acknowledge here is that this does not provide a criteria of language-hood, as Davidson sets out to do. Or, insofar that it does, it's something of a fiat criteria -- we know it's a language because we speak it.

But then I'm still compelled by this thought that we do just simply learn a language, rather than translate a language back into some other tongue -- else, how did we learn the native tongue?

edit: just to clarify a bit on my thoughts on Kuhn -- I tend to think of Kuhn, and Feyerabend's, claims as being a little more local than the more general place that Davidson is operating from. I read them of talking about science specifically, and scientific theories specifically, more than knowledge generally. Just to be clear on some of expressed resistance to Davidson's treatment. But I'll go along with the more general claim because I think with Kuhn, especially, it's easy to read him going both ways. -

The New Center, the internet, and philosophy outside of academiaRereading this thread just makes me miss Tgw :(

As far as I'm concerned these days, at least -- insofar that you're happy with your life, living a good life, then you're doing philosophy well. No need for recognition. No need to complete that degree. No need to worry about being in-between, too rigorous or not rigorous at all.

Happiness is all that matters. The rest is just for fun. And rigor can be fun. But it needn't impede your happiness. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeThank you for clarifying that. So your point is that there is no disagreement concerning the meaning of the words, the disagreement is about something else, some other "belief". So how do you construe the disagreement itself as being meaningful? — Metaphysician Undercover

In one case we disagree because I don't understand what you believe. In the other case we disagree even though I understand what you believe. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeAlright I can see that my attempt at demonstrative persuasion didn't work -- but I'm afraid I've lost the plot here Meta.

Meaningful disagreement, by my lights, is the sort of disagreement you have with someone while understanding the words they say. So we do not share the same belief. But I understand the statement the belief is about. edit: So its opposite is disagreeing with someone but not understanding the statement the belief is about -- so you don't really even disagree with their belief as much as you disagree with a statement, hence why it is a kind of meaningless disagreement -- a disagreement arrived at by way of not having the same meaning in mind. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeAs you're no doubt aware - having spent so much time on the forums - it's a rare thing for a mind to be ahubristic and circumspect enough to draw a distinction between its truths and its beliefs. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Granting that -- there is still a difference between true sentences, and a mind's truths, and a mind's beliefs.

A true sentence is: On the 25th of November at about 10 in the morning Moliere wrote some posts on the Philosophy Forum.

Now, unless we are frequenting this discussion, this surely wouldn't be a believed sentence. And, to be honest about my own beliefs, I didn't really believe it until I wrote it now. I don't get in the habit of documenting everything I do, I just go about and do it. But it was a true sentence before I believed it because that's what I was doing.

"A mind's truths" has the air of a different sort of thing, to me -- sort of like "We hold these truths to be self-evident". Things that are important to some mind that need no further explanation and which, if you do not believe, you just don't see The Truth.

Do you see the difference, in spite of what a mind might be inclined to do? -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeI agree the stock characters create an atmosphere of caricature. At the same time, I've encountered, on these forums, both simplistic reductive materialism and its immaterialist nemesis, duking it out in a nearly caricatural dialogue.

I've simplified my "stock characters" for the sake of clarity and non-complexity. The historical approach sounds useful too. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Cool. Just as long as we keep it in mind I think that's all that's needed -- since they are stock characters, it is we who are actually talking, putting words into their mouths, and what-not. So we can easily modify what they say along the way, too.

This is clear to me. We assume a background of shared belief and practice charity to facilitate communication. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Cool.

Rephrasing this to see if you think I understand you:

Broadly speaking, to facilitate communication (or "translation") charity and the presupposition of a background of shared belief are brought into play.

But in the case of ideological nemeses duking it out, charity is suspended and the presuppsition of a background of shared belief is abandoned.

In the former case, communication is the priority.

In the latter case, something like evangelism is the priority. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Yeah that's what I'm thinking. You see this sort of thing when you watch some of the debates between New Atheists and Christian apologists. The speakers are more addressing their audience than they are addressing one another. Sometimes that's not the case, but I've noticed that whenever they start to understand one another the audience also starts to lose interest. :D Or, at least, some of the audience starts to lose interest -- they wanted to see the bad guy taken to task, not understanding.

Also, I think it's worth noting that even in these cases, at least with respect to the Davidson paper, the two usually do understand one another -- the differences between these extreme beliefs is not a matter of untranslatability. It's a difference in emotional commitment to two beliefs that are percieved to be in competition -- it's a matter of a threat to one's identity, a psychological matter, and not a linguistic one where the schemes the two hold make it impossible for them to communicate, even partially so, or impossible for them to both be wrong. They can still both be wrong, or maybe just one of them be wrong. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Schemeah! That's... very nice and good. Thank you.

Gotta think.

Also, whilst I have fielded a few retorts today... well, you know -- family, life, and all that. Be back in a bit. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemePartial failure in as much as the immaterialist and materialist behave in a similar way, suggesting a common core of practical beliefs. I can't really imagine a case of total failure apart from examples of severe psychosis. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Cool.

So let's take a trip into partial untranslatability.

But first I feel it important to note that these are stock characters -- the materialist and the immaterialist. At least they are stock characters unless you happen to have some specific philosophers you have in mind. I mean I can imagine referencing Berkeley vs. Epicurus, as some sort of arch- versions of both, but they didn't speak to one another and I'm just conjuring them up as arch-examples.

I feel that's important to note because I'm kinda super into history-of-whatever. That's my jam. So stock characters stand as paradigmatic (to us) examples of thought, not as real examples. And the reason I like the historical approach so much is that it often dispels these phantoms of thought and imagination when we look closely.

So partial untranslatability. I will admit that the Ketch and Yawl example seems *extremely* close. And kinda. . .. uhhh... let's just say poor people have to google to understand it. All the same -- I think it makes sense to say that we do, in fact, reinterpret our conversation partners words to mean something else. They don't have to mean what we think they mean. And the closeness of the example is actually strong because it shows one case where we are very close but, rather than attributing a belief to another person, we accept the belief and reinterpret the words.

That's big.

And I think one good thing Davidson notes is that we do this on pain of not being understood.

So we have our stock characters. I think the more popular example of stock characters are the atheist materialist and the Christian spiritualist. In that situation -- might the people involved wish to be misunderstood? Maybe not consciously. That's a psychological matter. But maybe they just want to assert their belief and have others believe it.

I don't want this to be read universally. But, at least ,as an explanation for some -- maybe the examples we are all thinking of, I hope -- of our experiences with conceptual schemes?

Tell me what you think. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme:) Thanks. I feel the warm fuzzies of flattery.

-

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeConceptual schemes, as we encounter them in philosophical exchange, are generally centered on disconnective differences in belief. What is the significance, then, of reducing conceptual relativism to a difference in belief? — ZzzoneiroCosm

If we're talking about competing beliefs in talking about different conceptual schemes then we're not talking about two sets of beliefs that can both be true and mean different things, but simply two sets of beliefs; if the two beliefs contradict one another then, insofar that we accept the law of non-contradiction at least, at least one belief must be false (of course both could also be false, too, I would think -- given that real competing beliefs are not of the strict form, P or ~P, of the LNC).

The immaterialist (as defined here: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/7109/davidson-trivial-and-nontrivial-conceptual-schemes-a-case-study-in-translation/latest/comment) has a conceptual scheme: immaterialism. He believes the world consists entirely of mind.

The materialist has a conceptual scheme: materialism. He believes the world consists entirely of matter.

Reduce these conceptual schemes to beliefs and you have the same disconnect and very possibly the same relativism.

Would you say this sort of untranslatability is a total failure, or a partial failure? -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeYes. But he also does make an argument for this, too -- not just to accept it by fiat. And it's important to note, I believe, that this is in the section against total untranslatability. So even if meaning has more to it than the truth of convention-T -- we're talking about two languages which share nothing in common, no meaning whatsoever.

So German and English, for instance, can both express some similar meanings even if the meanings are not exactly the same. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme@Banno Alright, I'm finishing up now

Do we understand truth independently of translation?

Davidson answers no.

In short he does this because convention T embodies our best intuitions about how the concept of truth is used. And convention T allows us to get at the meaning of a sentence by taking truth as fundamental, or more specifically, taking "...is true" as fundamental and, through that, can translate German into English (or other languages too). Without truth -- without this convention T -- what could translation amount to?

Much thanks for your help on that one .

I think I have more to say on that later, but for now I'm just focusing on getting the argument right.

But basically this ends the argument against total untranslatability -- since there is no criteria we might list which allows us to make sense of a scheme which is both true and untranslatable, including all the myriad ways that various authors have tried to do, we must let go of this notion of conceptual schemes. And so we move onto partial untranslatability.

Here we return to what seemed to me a side-point at the beginning -- the closeness between meaning and belief. And we get a little more explanation, that this interdependence (a relation spelled out?) comes from the attribution of beliefs and the interpretation of sentences. And he argues for this by asking we grant that a man's speech cannot be interpreted (correctly?) without knowing a good deal about what he believes.

But, then, to know a good deal (as he puts it "fine distinctions between beliefs") about what he believes we must understand his speech.

On the face this is plausible to me. Sarcasm and irony can use the exact same sentences, but wouldn't be understandable as such -- the meaning of the sentences wouldn't be understood -- without knowing our speaker's beliefs (construed broadly). These aren't the only modes of speech that change the meaning of sentences with the exact same words in them, but I think it demonstrates the point.

If we are to intelligibly attribute beliefs or interpret speech we must, then, have a theory which simultaneously accounts for these, without begging the question.

For this paper Davidson proposes the attitude of "accepting as true", while noting that there's more to the story for an entire theory that answers the question -- but that this is enough to make his point about conceptual schemes.

I'm not sure I understand the abstract argument he proposes to allow this, but I'm also fine with, at this point at least, just granting the point about "accepting as true". The example that explains the general argument makes enough sense to me. Yes, we do reinterpret how our conversation partner's use words all the time. I fully grant that. In fact the further point he makes later is something I've stated a few times before -- that (meaningful) disagreement takes place on a background of agreement.

Now I have to admit though that I don't know what Davidson means by charity is a condition of a workable theory. Meaningful disagreement, and the desire to be understood? All these make sense to me. But I don't know what he means by "a workable theory" here -- a theory of translation or interpretation or of the original problem introduced which he answers with "accepting as true"?

But the point, going back to partial untranslatability, has more to do with how charity is not an option, but is forced upon us.

And so, having it forced upon us, if we translate an alien sentence -- one rejected by the aliens but the translation is beloved by ourselves, as a community -- we may be tempted to call this a difference in schemes. But we must make maximum sense of the words and thoughts of others when we make an effort to optimize for agreement (i.e., interpret charitably). And so conceptual relativism is really nothing more than a difference of belief or opinion. And there is no way to say that the difference is really in our concepts or our beliefs, no indication that this is a conceptual scheme.

In a very short summation: because we must accept charity, on pain of not being understood at all (in which case, what are we talking for), it follows that partial untranslatability falls apart or basically reduces to nothing more than a difference in belief.

Davidson closes with a somewhat elliptical, to my mind, conclusion. It seems to me that the paper is done at this point, but the last two paragraphs serve as what he believes he's demonstrated, at least. One, just as we cannot say that schemes are different, so we cannot say they are the same. But I think I might side with saying that by this Davidson means that such talk is unintelligible, so should be set aside -- at least, it is unintelligible the moment we make it clear.

Then Davidson wants to remind his readers that giving up this distinction does not land us in a land without truth at all. Even without "objective truth" as he puts it. Davidson wants to clarify, though maybe it is difficult to see for some dependent upon the third dogma of empiricism, that this dogma obscures objective truth -- and by putting it to the wayside we still have true sentences. Sentences which, being sentences, are relative to an actually existing language. But true all the same.

The elliptical part, for me anyways, is perhaps just a bit of poetic stretching on Davidson's part. But it speaks better for itself:

In giving up the dualism of scheme and world, we do

not give up the world, but reestablish unmediated touch with the

familiar objects whose antics make our sentences and opinions

true or false.

Seem to betray some of the previous points, but you gotta have a nice conclusion, yes? :)

Probably call it there for a night. Long day. But I'll pick up the conversation again tomorrow. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeThis is very much the conclusion I'm coming to as well. The only exception to that is Kuhn. The article specifically 'attacks' Kuhn and yet it feels like Kuhn is talking about the sorts of models I'm discussing (or there's some overlap, might be more accurate). — Isaac

I got that feeling, too -- or, at least, that my reading of Kuhn/Feyerabend differed enough from Davidson to make me want to make some kind of distinction. Even in the quotes Davidson provides I sort of raised an eyebrow of their translation into Davidson's idiom. But I'll admit that I don't know the papers he's citing, either.

Also Kuhn, at least, is just like that in general -- he's easy to get different impressions from. Like Rousseau: you read him because he says interesting things worth pondering, not because he said them precisely.

Off to work now but will finish the paper tonight. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeCool. Will do, though I'm chunking it because, hey, I still gotta work and I get tired too :). It's helping me too just to directly write out the argument.

Onto Scheme-Content and the third dogma of empiricism.

The paragraph I stopped at works as a closer for the previous discussion, by summarazing the difference between the two kinds of conceptual schemes, and introduces the second kind -- where empirical content is retained without an analytic/synthetic divide -- as a way to segue into the third dogma of empiricism.

Here Davidson takes some representatives of the view he wishes to criticize -- Whorf, Kuhn and Feyerabend, and Quine. He begins with Whorf but then provides us his distillation of the elements of these views right after he quotes Whorf:

Here we have all the required elements: language as the organizing force, not to be distinguished clearly from science; what is organized, referred to variously as "experience," "the stream of sensory experience," and "physical evidence"; and finally, the failure of intertranslatability ("calibration").

Here Davidson points out that there must be some neutral-something, something which conceptual schemes are about in order for the claim about conceptual schemes to make sense at all. In Whorf's quote we have the stream of sensory experience, and as Davidson interprets Kuhn at least in Kuhn it is nature, for Feyerabend it is human experience that's an actually existing process, and in Quine it is simply "experience". He also notes, through Quine, that the test of difference is a failure or difficulty in translation.

This is all of what we may call the historical-empirical material from which Davidson is drawing both his generalzations and also characterizing his target more in-depth. He sums up before giving us some more specific categories:

The idea is then that something is a language, and associated with a conceptual scheme, whether we can translate it or not, if it stands in a certain relation (predicting, organizing, facing or fitting) to experience (nature, reality, sensory promptings).

There exists an x which counts as a language. And said x is associated (related?) to a conceptual scheme IF it stands in a certain relation to experience.

So we get our categories for these sorts of conceptual schemes -- this by way of making conceptual schemes more intelligible to show how they are not defensible -- and conceptual schemes either organize or they fit.

A table of terms that are associated with both organize and fit (because I found the wording confusing):

Organize | Fit

systematize | predict

divide up | account for

| face (the tribunal of experience

And the entities, broadly, that are organized/fit are two categories as well -- either reality or experience.

****

The next two paragraphs are an argument against conceptual schemes which organize reality. I had to read it a couple of times but I believe the argument is best understood starting with the conclusion -- conceptual schemes which are claimed to organize reality are not adequate to the task of total untranslatability, as is the focus right now. If we are to organize reality, then we might organize a closet, say, and put the shoes here and the ties there. But what we cannot do is organize the closet without organizing all the objects within the closet -- we cannot organize the closet itself. There's a multiplicity of objects. Similarly so with predicates in a language -- we cannot organize a language itself without also organizing the predicates (say in relation to each other or their truth-values in some set of sample sentences). There are points within a pair of languages where the predicates differ, but there's enough similitude in our beliefs that we are able to point out these differences and know them rather than have them stand as alien artifacts, incomprehensible.

Davidson moves onto conceptual schemes which organize experience, and claims that this problem of plurality haunts these as well -- in fact points out that the language which we are familiar with seems to do exactly this! But then such a conceptual scheme would not supply us with the criteria we are looking for: a criteria of language-hood that does not depend upon (entail) translation into a familiar idiom.

He also moves on to point out that conceptual schemes which organize experience make an additional trouble for the search for this criteria: if it only organizes experience, then it does not organize knives and other familiar objects which are also in need of organizing.

Then Davidson segue's into the other pair of categories: conceptual schemes which fit (or, in the segue's word-choice, "cope") -- though having talked about the difficulties with conceptual schemes that (organize/fit) reality or experience he doesn't break out these sorts of conceptual schemes into their pairs this time -- he just focuses on conceptual schemes that fit, rather than organize.

Here he marks another difference between the two categories of conceptual schemes -- whereas the former looked at, in his words, the referential apparatus of language the latter takes on whole sentences.

Davidson mentions some particular views that we may have in mind, but wants to clarify and name the general target of his argument:

The general position is that sensory experience provides all the evidence for the acceptance of sentences (where sentences may include whole theories)

and then after some explication, the counter-argument:

The trouble is that the notion of fitting the totality of experience, like the notions of fitting the facts, or being true to the facts, adds nothing intelligible to the simple concept of being true. To

speak of sensory experience rather than the evidence, or just the facts, expresses a view about the source or nature of evidence, but it does not add a new entity to the universe against which to test

conceptual schemes

which is, after all, what Davidson is after. There's more here about truth, and a reference to another paper by Davidson. But let's just take him at his word and maybe save that paper for another time to at least understand the argument we're dealing with here. At least, for now. I'd like to finish this closer reading sometime :D.

This isn't to downplay the importance of that paragraph though because it's what carries us to Davidson's conclusion about conceptual schemes, the target of this paper.

Our attempt to characterize languages or conceptual schemes

in terms of the notion of fitting some entity has come down, then,

to the simple thought that something is an acceptable conceptual

scheme or theory if it is true. Perhaps we better say largely true in

order to allow sharers of a scheme to differ on details. And the

criterion of a conceptual scheme different from our own now becomes: largely true but not translatable

Some quote-dumping, but I actually found Davidson very clear at these parts so I thought it better to just put up his words. Mostly I'm just talking out some of my markings to see how the paper fits together as an essay and understand the argument better.

But here we change gears again. I think this section largely covers Davidson's characterization of the third dogma of empiricism, at least through the lens of conceptual schemes -- which is the target that brings out this third dogma in the first place. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeA new culprit emerges in the next paragraph -- Strawson. This by way of introducing two different sorts of conceptual schemes, the contrast point being Kuhn, so Davidson may focus on Kuhn's conceptual schemes.

The difference, as Davidson sees it, is in the kind of dualism proposed by the conceptual scheme. Strawson's is one between concept and content within language, where some statements are true by virtue of their meanings, and some are true because of the way of the world -- and that the synthetic statements are the one's of interest in talking about possible worlds, ala Strawson's take that we are imagining possibilities.

Kuhn's is one between language and uninterpretted content -- and is an approach that Davidson describes as giving up the analytic/synthetic distinction which Strawson's relies upon. And he lays out how an adherent to Kuhn might attack Strawson in order to introduce a way of telling when a new conceptual scheme comes about -- or for generating new conceptual schemes.

We get a new out of an old scheme when the speakers of a language come to accept as true an important range of sentences they previously took to be false (and, of course, vice versa) . . . A change has come over the meaning of the sentence because it now belongs to a new language.

Which is Davidson's parsing of Feyerabend's argument against meaning-invariance, the attack against what Davidson characterizes as Strawson's conceptual scheme.

What we get in the argument for the ministry echoes the argument against transitivity. How would we know that our New Man spoke with the new words of materialism but did not speak with the old meanings of mental furniture? We wouldn't. Speaking some words does not give us evidence of this cleaning up, of coming to a new conceptual scheme from our point of view as ministers -- again restating a theme about how we cannot come to some position outside our own in judging what others mean. So this other approach does not provide us with a means for determining a difference in conceptual schemes, either, though it does give up the analytic/synthetic divide.

This bit is weird to me:

So what sounded at first like a thrilling discovery - that

truth is relative to a conceptual scheme - has not so far been

shown to be anything more than the pedestrian and familiar fact

that the truth of a sentence is relative to (among other things) the

language to which it belongs. Instead of living in different worlds,

Kuhn's scientists may, like those who need Webster's dictionary,

be only words apart.

But, at the level of essay at least, it at least explains what Davidson believes and provides a bridge to his next point: introducing the third dogma of empiricism, the dualism between conceptual scheme and empirical content.

And here, I think, we can say Davidson changes gears again.

In summary what Davidson was doing here is quoting some of the culprits of conceptual schemes, and leading them down his line of thinking for why it is they are not adequate to the task of delineating conceptual schemes one from another. And the conclusion to this bit is that in the background there is a third dogma of empiricism, which he wishes to demonstrate as having the dual properties where it must either be intelligible or defensible, but cannot be both of these at once -- and so should be rejected.

So we move onto characterizing this dualism of scheme-content. In the next post. Might call it a night here? Starting to get tired. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeSo I set out to try and do as you did and summarize the argument Davidson is making into as brief a post as possible. Just to make sure I'm tracking.

He opens with some examples of the phenomena under consideration, and accepts the doctrine that languages differ -- ala Whorf -- with conceptual schemes, or having a conceptual scheme is the same as having a language with the exception that speakers of different languages could share a conceptual scheme provided we are able to translate from one language to another.

He briefly rejects mental phenomena sans language to get underway with what he's interested in focusing on -- translation between conceptual schemes. He also briefly denies the possibility that a person could shed their point-of-view in order to compare conceptual schemes. Kind of interesting there. In short these aren't argued for as much as they are setting out the landscape of interest for Davidson, with particular names that he's targetting: Kuhn, Quine, Whorf, and Bergson being the named culprits at this point.

Then the part where he begins to talk of total failure of translation and in reading closely felt like this was a doozy of a sentence.

: nothing, it may be said, could

count as evidence that some form of activity could not be interpreted in our language that was not at the same time evidence

that that form of activity was not speech behavior.

Philosophers, if nothing else, are demons of theses.

Attempting a bit of an untangle:

In indicating (through evidence) an activity is interpretable into English we also indicate, every time, that this same activity is speech behavior.

What a tongue twister! But what Davidson says is he does not wish to take this line, though he believes it to be true, but wants an argument for it.

In effect it seems that Davidson is trying to find a way of identifying what counts as a language at all, and does not want to simply assert that translation into English is the criterion of language-hood because he thinks that simply asserting it somehow compromises his argument, or at least is unsatisfactory as fiat and needs an argument.

The next paragraph reads like a digression to me where he talks about the closeness of translatability to being able to understand another person's beliefs, like a person who believes that perseverance keeps honor bright -- up to a point that there cannot be doubt, so Davidson says, that translating someone else's language is a very close relation to attributing complex attitudes like this to someone else. But he admits this is just to improve the plausiblity of the position he wants to argue for first rather than just take as true, and that he needs to specify more closely what this relationship is before making a case against untranslatable languages.

So he takes on a counter-argument to the notion that translatability cannot count as a criteria of languagehood -- that language translation is not transitive, at least in a hypothetical telephone-game sort of way. He states this is not a good argument because we would be unable to tell if the Saturnian was translating Plutonian when we ourselves could not translate Plutonian (harks back to the part of the essay where Davidson says we cannot relieve ourselves of our point of view) -- that we need not even have a chain of hypothetical languages, but rather that the problem is introduces in the very first case where there is not a transitive relation between two languages. If we speak English, and Whorf speaks German, and the Hopi speak Hopi, then how are we to know that Whorf is translating Hopi into German when we only speak English? How is it that Whorf is able to speak all three and we are not?

And then the gear change.

I have to say, up to this point I've sort of wondered what all this is for really. It's a bit messy and all over the place upon a closer reading. But there has been some term-setting, some brief mentions of different approaches that Davidson thinks problematic but not being focused on at this time, and some clarification of his own intentions.

I think we can summarize by saying that there are some adherents to conceptual schemes that Davidson wants to address, that he wants to address these adherents through the lens of translation and intertranslatability of languages, and that this naturally raises to the question of what counts as a language at all, and why translation should be seen as important for a criteria of language-hood in spite of arguments otherwise.

I think I'll save the gear change for my next post. But tell me if you think I'm totally off please. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeThis helps, thanks.

I'm ruminating. Plus about to get ready and have a good old boardgame night with friends. :D But thanks for working on the reply. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeI'd say that comes from page 2 of the essay:

What we need, it seems to me, is some idea of the considerations that set the limits to conceptual contrast. There are extreme suppositions that founder on paradox or contradiction; there are modest examples we have no trouble understanding. What determines where we cross from the merely strange or novel to the absurd'?

We may accept the doctrine that associates having a language with having a conceptual scheme. The relation may be supposed to be this: if conceptual schemes differ, so do languages. But speakers of different languages may share a conceptual scheme provided there is a way of translating one language into the other. Studying the criteria of translation is therefore a way of focussing on criteria of identity for conceptual schemes.

And so on. He briefly touches on beliefs where language and conceptual schemes are not related in this way, but he's focusing in where they are believed to relate this way with the intent of coming up with some clear-cut way of determining what counts as a conceptual scheme in the first place. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeIt's a very smart paper that caters to my approach, and which drew my interest because -- which may be predictable -- I meant to disagree with it. :)

Though perhaps less so now.

I've finished reading The Very Idea... again.

Going back to this here: -- I think I see why I got stuck on Tarski. For one he's dense as all living hell. But also Tarski kind of seems to play the lynch-pin in the argument. I'm not grasping coming from the generalized form that Davidson cites

"S is true iff P"

to the conclusion that we could not make sense of a simultaneously true and untranslatable "x" -- I'm not grasping why truth is so important to translation. Or to quote Davidson -

...there does not seem to be much hope for a test that a conceptual scheme is radically different from ours if that test depends on the assumption that we can divorce the notion of truth from that of translation.

Perhaps not an assumption. It should be argued for. But I first needed to understand just why truth is so important to translation. It seems that Davidson believes this to be so because without taking such and such a person's beliefs to be true we would be unable to communicate at all -- that there is a kind of kernel of truth (edit: too poetic -- that we must hold beliefs true for another in order to translate?) to making sense of one another. And it seems we do this all the time.

But to list where my suspicion is coming from -- not to persuade -- I think of the opposite also happening; a kind of phenomenological argument. There are times when there's a bed of agreement upon which meaningful disagreement takes place, and there are times when I don't know what another person means and feel this exact sort of disconnect. Which doesn't preclude a bridge, of course, but it seems to me that we encounter what Davidson lays out as an incoherent idea. But this is definitely not the sort of approach which would convince an advocate of Davidson, I'd think, because it is phenomenological and drawing from influence of existential authors.

So onto persuasion, or perhaps a deeper understanding. What's the deal with truth in Tarski? Is it not possible for there to be two languages (reading with Davidson that this is closely analogous to conceptual schemes) with some sentences that are true and are not translatable into one another? I mean I guess in the silly case we could say "The snow is white" is true iff Der Ozean ist Wasser. But that's not what's meant, I think. Would the argument for incommensurability be required to supply two such sentences? And, if we ramp up the charity, couldn't we show how such an example is actually translatable? -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeDigging through some of my notes on this --

https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.4057

is a paper that argues in favor of your notion of translatability from the historical perspective while using one of the classic examples Kuhn liked -- from Aristotle to Newton.

My take-away from this was that we can translate one project into another. But I wonder, along the way, what is lost from Aristotle in the translation? What motivates Kuhn to talk of paradigms, where Rovelli wishes to demonstrate harmony between supposedly different worldviews?

And it was probably around this time that I began to have a shift in interests with respect to philosophy that took me down just entirely different paths than science and its history. Hence why I'm still just right here on the issue. :D I just thought you might enjoy the paper. -

Davidson - On the Very Idea of a Conceptual SchemeI have a vague recollection of Feyerabend talking as if language games were incommensurable. If he did, I think he was wrong. Chess 960 is still chess. — Banno

Me too. But it's been awhile. Even visiting this paper has been awhile. I remember getting the gist of it and thinking it a strong argument, but getting caught up in understanding Tarski.

Been enjoying the recap. -

What’s your philosophy?Aighty. I suppose I'll pick out ones I can formulate an answer to then.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter?

Because it is pleasurable.

Bonus question: How do we get people to care about education and knowledge and reality to begin with?

We do not get people to care. This is not how care works. People care about what they care about -- and to know what they care about all you need to do is listen to them.

The Importance of Knowledge

Why does is matter what is real or not, true or false, in the first place?

To the extent that one's desires are frustrated knowledge is important. Knowledge is a tool or a toy and nothing more.

The Institutes of Justice

What is the proper governmental system, or who should be making those prescriptive judgements and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking?

There is no such thing as a proper state or governmental system. Any one state is relatively good to the extent that they help people -- and not just citizens -- satisfy their needs. If they fail in doing that they are relatively bad. It is not easy to describe or sum up the relative worth of a society -- there are relative goods and bads within every society that we have to judge individually. Not all needs are congruent or comparable. And the ones who should make the judgments are the one's effected by said judgments. -

What’s your philosophy?I have no such system.

Also, I'm not so sure that I'm even trying to build one.

There are a handful of questions I enjoy exploring. I especially enjoy going through ideas and thoughts with others insofar that I feel I can progress the dialogue.

Somewhere along the way philosophy seemed unfinished and boundless.

The attraction to systems diminished with that impression -- which is not to eschew systematic thinking, per se, but to be less concerned with the coherent end-product of a system of propositions. -

Former Theists, how do you avoid nihilism?interesting thought, but it's not so much that I need a big story for motivational purposes, I do seem to still care about making the world a better place. but for me what's missing is the underlying structure and framework that allowed me to make sense of what making the world a better place meant. Now I simply have no clue, without absolutes and with the indeterminacy of the meaning of words, I am left with the sense that really all that directs us is self interest veiled in appeals to truths like fairness, justice, equality that are ultimately linked to a world view where those things had meaning because God gave them meaning. I can't escape the thought that those concepts make as much sense in the human world as do they with respect to a pack of wolves... — dazed

Right. So you care about making the world a better place, but you don't know how to make the world a better place because you have a new belief -- a belief about the self, the world, and everything. Hence my calling it a Big Story.

So my question to you is -- if the new belief isn't working, as you would like to make the world a better place but find it difficult to answer what that means because of the new belief, then why hold onto the belief that we are brains spewing out narratives, that all our moral talk is actually veiled and directed by self-interest, that this renders such moral talk meaningless?

What is still compelling you to believe it, given that this very belief is going against your self-interest in fulfilling a desire for a Big Picture morality, where you strive for the greater good and feel good about it? -

Former Theists, how do you avoid nihilism?An even deeper engagement would involve caring about causes, positive societal change, the greater good. I used to be engaged and care about trying to better things (when I was a theist). Now I have no interest in those things because I can't define what positive or good would really mean on a macro scale. I just stick to the micro where it is usually more easy to define what is good for those I actually interact with. — dazed

You do not care about causes, positive societal change, or the greater good -- but you care about what caring about those things did for you, it seems - because you felt better maybe?

So why not pursue the causes, positive social changes, and greater goods based upon what makes you feel better?

But perhaps that's not as satisfying. Perhaps it's better when we have a big story about purpose and origins to justify caring about these things, but if it's all just brains in bone-boxes responding to feelings selected by a historical and evolutionary process then the big story just isn't as inspiring anymore.

Why is that, I wonder? I mean why isn't the Big Story of the self as a string of narratives spewing forth from the brain nowhere near as satisfying as the Big Story of the immortal self set in some eternal plan within a purposive universe? What did Jesus have to do with immigrants, besides saying some pithy things about love that any brain could have (well, I'd probably go so far as to say *did*, given that I don't believe) come up with?

You say it is because your brain is set for Judeo-Christian meaning and purpose. But nothing could substitute Judeo-Christian meaning and purpose; it would be atheist meaning and purpose, or democratic meaning and purpose, or Buddhist meaning and purpose, or whatever-else-it-is. It would always be a different Big Story. But something about the brain-making-stories Big Story isn't satisfying. . .

So why stick to it? -

Hate the red templateIt's the latter that I like it for. But alas, that's merely aesthetic. Blue was a nice, soothing color.

Moliere

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum