-

Bringing reductionism homeBut to reduce myself to anti-reduction would be terribly reductionist, don't you think?

;) -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistWhy does it bugger belief?

I don't think that it is common sense or obvious that political power influences the hard sciences. Many people seem to resist the idea. -

What do you care about?I agree with you on the latter point, now. I just had to read the text again to see why I thought that, and came up short. Thanks for the clarification.

-

What do you care about?I'm reading this article, though, and I don't think he's opposed to the law of inertia. He's opposed to the term "inertial force" -- because a force is what acts on an object or is the cause for a bit of matter's changing course.

EDIT: That was a really cool article. Just finished it now. Thanks for sharing it. -

What do you care about?I decided to track down the quotes I was thinking of in making my assertions. I found that I've made a mistake in saying Newton is the counter-example to Humean causation. What I was thinking was Newton, but that's not really stated in the quotes I was thinking of.

Something very much like the argument I outlined is there -- but not Newton. So, my bad there. But, to go over the quotes I was thinking. . .

In the preface to the 2nd edition, at the end of Bx:

Two [sciences involving] theoretical cognitions by reason are to determine their objects a priori: they are mathematics and physics. In mathematics this determination is to be entirely pure; in physics it is to be at least partly pure, but to some extent also in accordance with sources of cognition other than reason

That's definitely the quote I was thinking of in saying Newton, though this in particular doesn't link physics to Newton (as K. was definitely interested in physics at large, and not just Newton), or how that might serve as a counter-example to Humean criticisms of causation.

Later, on B21 there is a footnote in the introduction to the second edition, 2 paragraphs after introducing the central question of the critique, to these lines:

How is pure mathematics possible?

How is pure natural science possible?

Since these sciences are actually given [as existent], it is surely proper for us to ask how they are possible; for that they must be possible is proved by their being actual.

And the footnote reads:

This actuality may still be doubted by some in the case of pure natural science. Yet we need only examine the propositions that are to be found at the beginning of physics proper (empirical physics), such as those about the permanence of the quantity of matter, about inertia, about the equality of action and reaction, etc., in order to soon be convinced that these propositions themselves amount to a physica pura (or physica rationalis). Such a physics, as a science in its own right, surely deserves to be put forth separately and in its whole range, whether this range be narrow or broad

To this footnote the translator adds a footnote of his own, appended to the last sentence:

This Kant did in his Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (1786), Ak. IV, 465-565

This is where I got the notion of him deriving Newtonian physics, but surely Newton is not mentioned here either. Nor is the notion of Newtonian physics serving as the counter-example against Humean skepticism.

Earlier in the introduction, under II. "We are in Possession of Certain A Priori Cognitions, And Even Common Understanding is Never without Them" at B5 Kant stated:

...Now, it is easy to show that in human cognition there actually are such judgments, judgments that are necessary and in the strictest sense universal, and hence are pure a priori judgments. If we want an example from the sciences, we need only look to all the propositions of mathematics; if we want one from the most ordinary use of understanding, then we can use the proposition that all change must have a cause.

This is getting closer to how Kant is in disagreement with Hume, and highlighting a sort of principle which the common understanding uses (though, perhaps, this principle isn't something that Newton uses -- again, no support for that particular claim of mine).

Later we get closer to the language I used, albeit admittedly not with Newton referenced. I'll just note here I'm now uncertain why I thought Newton in particular to Hume. Kant certainly references Newtonian physics throughout the CPR, but I overstepped in stating that it was Newton who served as the counter to Humean skepticism, I believe, unless there's some reference I missed. However, even in that case I overstepped, because after reading this highlighted portion I'm pretty sure this is where I was getting everything I stated before. So even if the reference is there, I was in error because these were the sections I was thinking of anyways.

Mea culpa.

At B127, or in the section titled "Transition to the Transcendental Deduction of the Categories":

The illustrious Locke, not having engaged in this contemplation, and encountering pure concepts of understanding in experience, also derived them from experience. Yet he proceeded so inconsistently that he dared to try using these concepts for cognitions that go far beyond any boundary of experience. David Hume recognized that in order for us to be able to do this, the origin of these concepts must be a priori. But he was quite unable to explain how it is possible that concepts not in themselves combined in the understanding should nonetheless have to be thought by it as necessarily combined in the object. Nor did it occur to him that perhaps the understanding itself might, through these concepts, be the author of the experience wherein we encounter the understanding's objects. Thus, in his plight, he derived these concepts from experience (viz. from habit, a subjective necessity that arises in experience through repeated association and that ultimately is falsely regarded as objective). But he proceeded quite consistently after that, for he declared that we cannot use these concepts and the principles that they occasion in order to go beyond the boundary of experience. Yet the empirical derivation of these concepts which occurred to both cannot be reconciled with the scientific a priori cognitions that we actually have, viz., our a priori cognitions of pure mathematics and universal natural science, and hence this empirical derivation is refuted by that fact.

That last sentence, in particular, is pretty much what I was thinking of. I believe I must have basically interpreted "universal natural science" as equivalent to Newtonian physics, though by no means is that asserted here.

The facts, though, which are meant to stand as counter-examples to the Humean account of causation are the sciences of pure mathematics, and universal natural science. -

What do you care about?I'm running on memory here, but my understanding was that Newton's principia, ala Kant, was partially a priori synthetic and partially a posteriori. So it was both empirical and logical -- not transcendental, but rather a sort of fact which couldn't be true in light of Hume's critique of causation.

Or, maybe a better way to say it: a fact which is true, while Hume's critique of causation also seems true, and these two things cannot both be true.

So I don't know if I'd say he was out to defend Newton, or provide a foundation for him either, as I said before. Rather, Newton is given as a kind of evidence for our having knowledge of causation in spite of Hume's critique. -

What do you care about?Me too. CoJ is definitely a book I'll be rereading again.

I have access to the Opum Postumum, but my eyes kind of glazed over when I tried it, to be honest. :D I was kind of "Kanted out" at the time. I do want to read it some day though. -

What do you care about?For two, it seems like an attempt to enshrine contemporary physics forever by fiat, instead of doing the reasonable thing, which is admitting that while explanatorily powerful, the Newtonian picture was without epistemic foundation — The Great Whatever

I think the tension between the problem of induction and the necessity which we see in the world with Newtonian physics is what's at issue more than a foundation, per se. He intended to derive Newtonian physics from the categories eventually, but I think it's the implication of Newtonian physics -- that we will know where the cannon ball will land, that the sun will rise tomorrow, and we know these things partly based upon a priori knowledge -- more than asking after foundations is what's the goal. (or, goal? Maybe focus is better -- Hume's critique of causation vs. the fact that Newtonian physics shows we have knowledge of causation as the tension) -

What do you care about?Not in any precision. Vaguely, I seem to recall the way he talks about God in that section seemed to at least get very very close to the noumena. I think he meant to place the power of judgment somewhere between pure and practical reason, but the way he talks about God in CoJ seemd to contradict the way he talks about God in CPR.

-

What do you care about?That sounds about right -- of course it's been a long time for me too. We got through the aesthetics, I remember -- we got stuck on the second half on teleological judgment where an uncharitable first reading on my part was "sooo ... you can know the noumena" :D

-

What do you care about?Actually, this convo does go back to an old question which I'm still interested in, but not currently pursuing, @csalisbury

I remember we stalled at CoJ because of life and stuff, plus it was incredibly difficult. But I remember there was a tension between the CoJ and CPR, that you have already mentioned. I'd definitely like to explore that tension more.

Also, I picked up the CPR again maybe 6 months ago and found myself disagreeing with it along the way. But very much in a notional sense -- just getting a sense of disagreement. So one particular question that interests me is, "What is the best way to disagree with these arguments?" -- or, even, just outlining a rational disagreement.

All notional at the moment, and I'm reading other things, but Kant exegesis has been a long-standing question for myself. -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistSure.

It doesn't change my point, though -- that hard sciences are influenced by the workings of power.

Suppose a world with 10 true statements in it. If 3 of those statements relate to a specific interests, and 7 statements relate individually to there own interests, then focusing on the first interest may yeild more true statements than any other one interest, but it won't be some kind of totality of truth, even if one's methodology is the same. -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistIf you need me to reiterate -- this does not effect the truth of said theories. Things are true or not true, regardless of interests.

It's just the wider focus. -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistIt's not specific wars which fund research programs, but states, universities, and corporations.

Anyone who has had a go at grant money knows where the money is at. As I said, not all science is this way, but it's just a fact that these are the interests which have more funding. -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistYeah, but the people who study the physical world usually get funding to do so by catering to social interests -- as the hard sciences go that usually means catering to either war or medicine in some fashion.

Not always. Nor does this necessarily effect the truth-value of scientific knowledge. It just points out that said knowledge is often fueled by more than pure, objective interest -- but is directed by the workings of power. (When surely the physical world doesn't care for these things) -

Are humans bad at philosophy?Are people bad at philosophy? This would included professional philosophers as well as the rest of us.

First of all, what would it mean for everyone to be bad at philosophy? — Marchesk

The funny thing here is that there's a sense in which answering the question is to participate in the activity of philosophy. Only a sense -- I could see approaching the question in a manner which is a-philosophical; perhaps sociological, as a for instance. But it's worth noting here because if we answer in either direction that answer will sort of confirm itself, in a way. Yes, we are bad at philosophy -- look at how we answer the question. No, we are not bad at philosophy -- the same. The answer is recursive to the topic being asked about.

I'd take out the 'everyone' here and ask -- what would it mean for anyone to be bad at philosophy? Can we point to one act of bad philosophy? What about several bad acts of philosophy? Then it's just a matter of checking 'everyone' in some fashion.

Sophistry comes to mind here as the sort of arch-enemy of philosophy. We may appear to be philosophical, but we are only using the same tools of philosophy in a bad way -- to teach the well-to-do how to do well in court and congress so that they continue to pay our wages. (though said criticism came from one whose wages were not a concern due to already being aristocratic, it should be noted)

Then poor reasoning also comes to mind. It's not so much the specifics of our beliefs and arguments, but rather the 'form' of arguments which we propose do not hold up to rational scrutiny -- they are rhetorical ploys or make basic errors in reasoning.

I think it also comes down to the way we look at philosophy, too -- not just what counts as good or bad philosophy, but what counts as philosophy at all. Sophistry comes to mind here, too, but I've already touched on that. The institutions of philosophy, at least, change as do the particular focuses and concerns. And with that change in focus it seems that philosophy's goals change. Some have sought to improve upon the soul of the leaders of society, others to cure the soul of its ailments, others to change society at large, others to gain understanding or wisdom for themselves, others to build a science out of the classical philosophical questions, others to preserve what is naturally human in the face of a society which threatens that...

Goals are an easy way to determine good or bad, in general. Or, generally speaking rather. But with philosophy this isn't quite right. Debating, or considering, or at least thinking about the various goals and their methods and conclusions is itself the philosophical project. Or, even phrasing it like this seems to poison the well -- is philosophy even a project? Or is it just an inclination which humans have, like art and religion?

I think we are bad at reasoning. I think this has been empirically demonstrated, at least for our culture (as most empirical studies on reasoning are performed on bribed/coerced undergraduates ;) ). But I'm uncertain that I'd say this means we are bad at philosophy, per se. I think we can be bad at philosophy -- that's not what I mean. I don't mean to make philosophy something which can't be judged. It can be. But the very judgment is an act of philosophy, and it seems to me that philosophy, while very much concerned for reason and argument, is more than reason and argument.

If this is so, why is the human race poor at philosophizing?

I dunno. :D -

Is dictatorship ever the best option?It seems to me that every state believes what your friend states -- the disagreement isn't that there are some people with whom one must deal violently in order to have stability, but rather the manner in which you choose those people, and how violently you kick with it.

In the United States, for instance, we have the world's largest prison population. Our violence towards African American communities is far from bloodless, as well.

The appropriate distribution of violence is the business of the state. Whether that be a democracy or a dictatorship -- this is just a quibble on procedure in relation to that fact.

Which is just to say that your friend could only be wrong if one were an anarchist. Otherwise the disagreement is only about who deserves the boot and how those people are selected. I know which kind of state I prefer, but it's worth noting because it's not like your friend is wrong even by our own practices. He just thinks Assad is better than the alternatives. -

The ethics of argumentative scepticismWhere judicious skepticism can encourage one to withhold assent where uncertain, it too often features not as a useful heuristic in inquiry but as a substitute for it.

That was my favorite quote. It hits home, and also points the way to fight against what is not a worthwhile tendency by pointing out how skepticism should be used. -

Can humans get outside their conceptual schemas?Yes and no?

When I eat an apple I eat the apple -- I do not eat the concept of the apple.

But I know what the apple is by means of conceptualization.

But eating is not the same sort of thing as knowing. Acting is not the same sort of thing as believing. And what I know about is not the same sort of thing as how I come to know about it.

I'd posit that the question is a bit ambiguous -- in the sense that we can understand 'conceptual schemes' to entail either conclusion.

In one sense we could think of 'conceptual schemes' as nothing more than the set of beliefs that cohere together rationally. In which case, of course we have contact with things outside of our conceptual schemes, and thereby there is no need for us to ask of escape.

In another sense, we could say that in order for us to make sense of the 'manifold of experience' -- or for there to be a 'manifold' in the first place, more properly speaking -- there has to be some kind of conceptual structures in place for speech, or knowledge, to even take place. In which case there wouldn't be an escape, but there wouldn't even be the question of escape -- there would just be a limit upon what we could say, from a rational point of view.

To use your example of the ancient Hebrew's cosmology: Did anyone, then, come to believe differently? Probably not. And when different ideas have come to the fore it wasn't a matter of escape, I'd say, either -- but discovery, invention, and oftentimes politics.

Which, I guess, I'd just ask after this 'escape' word, really. I don't think that conceptual schemes are things we escape from. Rather, they are liberating in that they bring sense to the world. Also, I'd say that conceptual schemes are not permanent -- so there is nothing to escape from. Rather, there is a sort of play between conceptual schemes, and then there is the world we live in which is surely both mediated by our concepts and is also something which we compare our concepts to.

It's just a matter of not taking them too seriously, and not too lightly too.

... does that make sense? I'm sort of exploring at the same time as saying what I think... -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistAccording to Chomsky it was around the 1970s when a group of Parisian intellectuals and maoists (e.g. Julia Kristeva & Co.) could no longer deny the atrocities in Asia for which other maoists had been responsible. So, did they reconsider? No, instead they became outspoken post-structuralists who rejected the self-sufficiency of right, wrong, true, false, good, bad and so on. As I understand it they exploited problems of philosophy as a means to get away with a dubious past. — jkop

I haven't read Julia Kristeva. But I know that Deleuze, for instance, was inspired by the social unrest of 1968 in France in writing Anti-Oedipus. I also know that while Derrida indicates later on that he has Marxist leanings, he tried to remain aloof of the political scene in France. I point to 1968 just to note that the writers typically associated with post-modernism aren't necessarily maoists. (I am aware of maoists involved in 68, but it was far from strictly maoists, and certainly had a lot of on the ground political demands which were far away from China and maoist theory).

Not all Parisian intellectuals were maoists, of course. But most of them had (or still have) an obfuscatory style of writing which has the illegitimate benefits of making themselves (or their interpreters) the sole intellectual authorities of their claims, and thereby also immune to criticism. If one does not blindly accept their claims one runs the risk of being intimidated and accused for being ignorant.

I think a lot of it is hard to read. But I also think that Godel, for instance, is hard to read. With secondary literature and study it becomes easier, but it takes effort.

I wouldn't expect anyone to blindly accept any writer's claims. It's on this basis that I'm saying what I say, I suppose. Don't accept any of it -- just read it if you want to actively reject it. Or don't read it, but you don't need to have an opinion on it in that case, no?

I think postmodernism has little to do with philosophy, although demarcation seems to be a recurring theme. Kristeva, Derrida, Baudrillard, Foucault, Deleuze etc. became intellectual rock-stars by making all kinds of outrageous claims embedded in impenetrable jargon which attracted the intellectually curious as well as those with a grudge against established knowledge, skills, or habits.

It is not over yet, though. Currently many professors at our universities are old fans of these rockstars. Most graduates from my school of architecture know very little about how to build, because many of their teachers think it is naive to believe that there would be right or wrong ways to build. As if an absence of right and wrong would make us creative. But the way we build will therefore be determined by power instead of knowledge or rightness. I don't think that's so creative. — jkop

I suppose I'd just advise looking at the writers and criticizing them before criticizing the thing 'post-modernism itself', or at least just not having an opinion on them without reading them. That seems to me to be a pretty reasonable standard for criticism, no?

After all -- we wouldn't criticize a modern philosopher -- from Descartes up to wherever you draw the boundary -- just by belonging to that historical period. Clearly modern philosophers disagreed with one another. They have nuances which deserve attention. The understanding of the historical category is worthwhile for getting a broad overview, but it's not a way to reject all modern philosophers. -

How To Debate A Post-ModernistIt's a fair question, though, especially considering you characterizing yourself as one who is at least in pursuit of truth. We may very well be lacking in understanding of post-modernism, and surely are lacking in understanding of what you are criticizing, but is there some way you came to understand "post-modernism itself", a way which is open to us as well?

I'd also note that while I know these names, I agree with @Cavacava that this is more of a historical period -- and sometimes I think the generalization of what post-modernism states seems to me to be unfair to what particular thinkers associated with the period actually state. -

Proofs of God's existence - what are they?I agree with @Thorongil's main point -- that there isn't some kind of ranking of importance between these various words, and they can be used interchangeably here.

Or do all you mean is to say that proofs of God are weaker than arguments which use observations and take the form of experiments?

One thing I think proofs of God are useful for is exploring argument, *especially* of the sort that doesn't rely as much upon observation. It's something that people care about so they pay attention -- and you teach them basic argument along the way. I don't think an argument needs to rely upon observation and experimentation to be worth consideration.

I don't think anyone is usually convinced by these arguments in either direction. But that's not necessarily the point. -

What do you care about?I don't think I have a specific question that gets under my skin at the moment. A lot of questions that were like that I've sort of come to find a peace with -- not that they aren't interesting, but they don't bug me as much as they had.

Topically, though, these days "the passions", or desire, or the emotions are a big focus of interest for me. It pretty much stems from my initial interest in ethics, itself an interest likely more due to personal history than anything.

But it's the sort of topic I've found to be self-reinforcing to study too. The more exposure I have to how people characterize the passions, the more I'm able to both understand others and myself, which is gratifying and not necessarily related to ethics.

I'm also interested in meta-philosophical questions -- where and when philosophy is proper, what counts as philosophy, what counts as good philosophy, and any sort of teleological considerations which we may attach to philosophy -- both descriptively and normatively. I think this is interesting because the reasons why people are drawn to philosophy are diverse and not necessarily the same as mine, one, and also because it gives a way of parsing the huge multifarious beast known as philosophy -- why one might reject a philosophical position or adopt it or expand it into other areas.

I suppose it's a natural sort of thing for someone whose just "into" philosophy to do after reading enough of it -- asking philosophical questions about what it is you've been putting your time into :D. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)Maybe so. I could see it doing so, at least, just depending -- but I think the real dispute between Sapientia and I is more along the lines of what it means to know and also what it means to trust -- in particular, with respect to science.

I think what you propose would seperate our positions neatly. But I am uncertain that said distinction would actually address where the disagrement is occuring. Not that said disagreement has to be resolved here -- maybe that should occur in another discussion -- I'm just noting why I am uncertain.

We could adopt this distinction, but at the same time I sort of wonder if it would resolve our real dispute -- though, for sure, I'm not sure if we even have a real dispute or if we have hammered down where the best point of disagreement is at at this point. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)It also, in contrast to my answer, lacks plausibility when it comes to accounting for optical illusions - at least those relating to colour and perception in a similar way to that of the picture of the strawberries. — Sapientia

This just begs the question, though. It is only an optical illusion if there is an illusion.

That in combination with what I've said about colour categorisation. And so does yours, does it not? Don't you similarly think that we can tell that the strawberries are red because the brain does such-and-such? — Sapientia

No, not at all in fact. All you need do is look at something to tell the color of something. That the brain is doing something to make the gray appear red seems to be the argument on the opposing side, by my lights.

Ha! Perfectly reliable? You might have gotten away with that if it wasn't for those meddling scientists, who came along and discovered that colour is inextricably related to light emissions, and that particular ranges of wavelength in normal circumstances cause us to perceive particular colours - and were thus categorised accordingly - almost without exception. Then exceptions were discovered, and this is one of them. Hence the grey coloured strawberries appearing red, hence the unreliability of your method. — Sapientia

Eh, scientists must make arguments like anyone else. I don't need to believe what a scientist has to say just because a scientist says it. There isn't such a thing as a valid appeal to authority in science. You can trust authority for certain purposes, and must do so very often in life, but that is no reason to believe something is true.

That's not how science works. You're perfectly rational to not believe something until you understand the demonstration -- you don't have to disbelieve it, either, per se. It doesn't have to be forbidden. But you certainly don't have to take a scientists word on anything.

That's, like, the whole point of science. It is open to anyone to interrogate and understand. It may take some time and effort to understand, and it's fair enough to say that you or I aren't up to snuff on a topic -- but that doesn't mean you have to believe anything. That's just anti-scientific thinking.

We do have an explanation. The brain is the mechanism — Sapientia

The brain is a black box. There are inputs and outputs being defined, but that's about it.

A chemical equation works in a similar manner.

H20 -> h2 + 1/2 o2

The "->" stands for "yields" -- while we may observe the beginning and ending products of a chemical reaction what is not demonstrated is the step-wise process which occurs. Many experiments are set up for the very purpose of determining the mechanisms of even singular chemical reactions. It is by no means an easy thing to determine, considering that you can't exactly observe the mechanism but, instead, have to infer it based on other measurements. (such as the rate of reaction, for instance).

So what I see when I hear "the brain does it" is "photons -> images" where "->" is "the brain does".

That is no mechanism.

One doesn't need to elucidate a mechanism within a mechanism within a mechanism ad infinitum or until you're satisfied, if that's even possible. — Sapientia

Why?

:D

So it's unwise to claim to know something in light of what the experts know, when we don't know it in the way that they do? — Sapientia

Yup.

At least if you're claiming the mantle of science. Scientific arguments are straightforward enough that given enough time they make sense. Claims of 'complexity' and 'difficulty' are just mystifications.

Evolution is probably my favorite scientific theory because it demonstrates this so very well. The arguments for evolution are easy to lay out and explain to someone. You have more advanced topics in biology, of course. But the overall theory of evolution? It is elegant and easy for most anyone of average intellect to grasp and understand.

No, that's not quite reasonable, because an explanation has already been given, just apparently not to your satisfaction. — Sapientia

"because", without qualification, is also an explanation. And it is the sort of thing one gives to stop questions, for certain.

But there's no reason to think that because this explanation has been given that one should be satisfied with it, or that it is reasonable either.

What counts as either a reasonable or satisfactory explanation, clearly, needs something more to it than simply that it has been given.

This is just to knock down the notion that because an explanation has been given that we must accept it as satisfactory or rational -- I don't think this is the explanation you are giving, just that it passes the criteria you're proposing here for the acceptance of an explanation as rational or satisfactory.

No need. This has most likely been verified by scientists before we were even aware of it. The work has most likely already been done, and we can appeal to these authorities. Or we could harbour unreasonable doubt. Perhaps it's all just a joke or a conspiracy! Yeah, I don't think so. In this case, it is valid to appeal to authority and to make certain reasonable assumptions about what was done to verify the hypothesis. — Sapientia

That's just bonkers. At the very least you cannot be claiming any kind of scientific value -- as you said earlier, 'to science' the problem -- if you aren't even willing to verify a belief with some kind of standard of measure, but just take it on faith that this was done. Even if the scientists have done this, it is on the basis of reproducibility that scientific argument is built.

You don't need to have faith in the priests of scientific knowledge that what they translate from the book of nature into the vernacular is the truth, may Darwin be praised. You just do the experiment yourself. You may do the experiment wrongly, of course, but so may they.

At least, insofar that we are defining color along the lines of wavelength, and not what it looks like, it does seem reasonable to ask -- what wavelength have you measured?

Some red isn't red though, is it? We're talking about grey, which, as we know, contains some red. But if you conclude that it's red on that basis, you'd also have to conclude that it's yellow, and that it's blue, and so on. Which is just nonsense. It's grey. — Sapientia

I conclude that it's red on the basis of what it looks like. This is my standard.

And you've focussed a lot on the brain - too much, perhaps - but don't forget about the established colour categorisation, and that whether or not something corresponds accordingly doesn't matter one iota about the brain. The brain has to do with why we perceive it a certain way, not why it is the colour that it is. — Sapientia

My focus on the brain is an extension of the argument for why the strawberries only appear red, when in reality they are gray. The brain, after all, is the causal agent proposed here.

As for what colour it is -- it seems to me that you're taking on faith that it is the color it is, since there hasn't been a measurement, no?

Or. . . maybe you're just using the standard I've proposed? Given what you have said about the lack of need to measure I'd say this is a fair inference.

You look at the pixel, it's gray, and therefore the strawberries are gray, because the strawberry image is made of the pixels, and color is the sort of property which translates from its bits to what it makes up, therefore the color of the strawberry image in reality is gray, though it appears red. Scientists explain the causal mechanism somewhere behind the scenes, but ultimately that's not what matters -- what matters is what color the pixels are.

But then you're just looking at the pixel to determine its color. Which is exactly what I've said we should do to determine something's color. It's just in the case of the strawberry, you believe the image stays gray because the pixels are gray. I'd say that without some kind of argument to the contrary, we should just determine color in the exact manner that we did the first time around -- by looking at it.

If we drop out the brain entirely, and we aren't measuring wavelengths -- and if we don't know what the brain is doing aside from vague hand-wavey references to 'color constancy', why should it be referenced at all except to say it does something somewhere? Which is hardly and explanation -- then the strawberry image is red, and the pixels are gray.

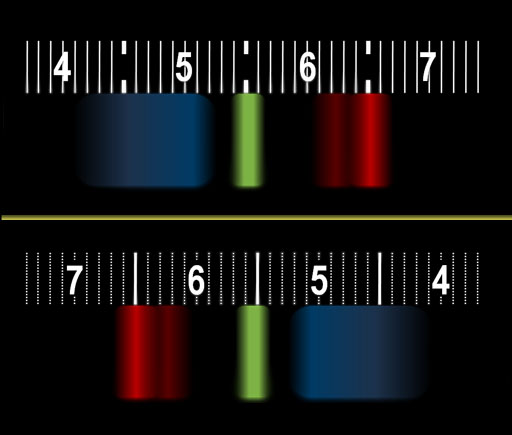

FWIW, I decided to hunt down some kind of image of monitors being measured by spectroscopes. The following websites abliges: http://www.chemistryland.com/CHM107Lab/Exp7/Spectroscope/Spectroscope.html

Assuming that their results are accurate:

This is what he got by aiming the spectroscope at the white portion of a screen. Not the image we're talking about, by all means, but this is what he gets.

What I don't see by looking at this is white -- I don't see how you get white from these results. I see how, knowing that when light combines such and such colors evenly you get white you can predict white. But I don't see how you get white from this. It seems to me that you must first know what white light looks like in order to know what colors you are going to get by combining this particular array of colors.

What would be of particular interest, I think, would be to see the spectroscopic results of one pixel compared to the entire photo. I don't think they'd be identical. I don't think anyone would think they'd be identical, either, for that matter. But if they're not identical, by your own theory of color, then the pixel and the image are not the same color, at least. Maybe you wouldn't go so far as to say they are red. You'd explain the difference in color by the differences in the gray palette of the picture, I'd say. That would save your theory.

But at the end of the day given that there are no such spectroscopic tests, I'd say that we really are just looking at such and such to determine such and such, and it is your belief that color is the sort of property which does not change as it aggregates into a whole which yields your belief that the strawberry image is gray, while it is my belief that we determine color by looking at it and there is nothing more to it than that which yields my belief that the strawberry image is red.

EDIT: 10 minutes after -- there's a very good image on that website which explores this difficulty more, too. The yellow one, when measured by the spectroscope, only comes out as a mixture of green and red -- it is not a 'pure' yellow, i.e. the yellow associated with the particular wavelength on the electromagnetic spectrum. Yet, clearly, the box is yellow.

Pointillism explores this notion quite well, too -- individual dots from a pen can be one color, but when you stand back, the picture is a mixture of the colors there. Impressionism does as well, and sort of pushes against the lay notion of color constancy presented in the pop articles so far -- that things do stay the same color as the light changes. But I'd have to know more about what is really be proposed to say for certain. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)And my question is: why do you ask, and why isn't that answer good enough for you? You could go and ask a neuroscientist who could probably give you a more detailed answer, although my guess is that you still wouldn't be satisfied. But why should I care? We only know what we know, and what we know enables us to answer the question in the way that I have done, which is good enough for the sake of this problem of perception, but perhaps not for some other problem that you seem to have introduced into the discussion. But this is a discussion about the former, and it need not digress into a discussion about the so-called hard problem to which you seem to be alluding. — Sapientia

Well, the question was "What colour are the strawberries?" -- and your answer is that they are gray, in reality, but red, in appearance. My answer is that the strawberries are red, while the pixels are gray. Your answer seems to rely upon some kind of mechanism which the brain does, no? So, we can tell the strawberries are really gray because the brain does such and such. It seems a natural enough question to ask what it is that the brain does to make it appear as such and such when in reality it is this or that. Or, at the very least, how it is you determined this, and why we might want to determine things differently in this case than in other cases.

I'd think you would care for the answer because it would explain your belief here. I suppose you don't have to care though. You could certainly just believe it's true because a scientist says it's true.

If the explanation boils down to the brain does stuff here like elsewhere that's not exactly persuasive when we have a perfectly reliable method for determining color, I'd say. If we don't have a mechanism, then the explanation really does amount to about the same thing as magic. It's like all the neuro- talk you see in the papers everywhere meant to explain everything -- and the explanation boils down to the same: "The brain made you do it"

Here, at least, there's this notion of color constancy, so there's a bit more than this -- but not much.

I'd suggest that we could at least admit that we don't know the mechanism, but presume that the strawberries are really gray because the pixels are gray, and it seems like this brain-thing does stuff with perception so we believe that it might have something to do with it. At least, we could say that maybe someone with more knowledge than ourselves -- of which I am certainly not the most knowledgeable on the subject, I hardly even qualify as a hobbyist -- might know, but we ourselves don't understand the process, and so it would be unwise to claim we know in the first place.

But if that were the case, then I'd also suggest that it is quite reasonable to believe the strawberries are red, since we determine the color of images and things by looking at them -- and that it is the one who is claiming to know the real reality that should explain themselves in light of this.

I didn't elaborate because I didn't think it necessary. You already know about this, don't you? And even if you don't, others in this discussion have gone into detail on this. There is an established means of categorising colour based on range of wavelength. That's what I was referring to, and you can look it up yourself if need be. This is what I'm appealing to when I make the claim that the strawberries are not red, and I do so because I think that it makes for a better explanation than the alternative which claims that they are red. I don't really want to go into further detail than that, since I've already done so in previous comments, and I stand by those comments. I'd rather you just address what I've already said on the matter, rather than reiterate from the starting point of this discussion. — Sapientia

OK.

And the whole point with the picture of the strawberries is that the wavelengths of light do not in this case correspond to our colour-perception! Our Colour-perception is red, but the wavelengths do not correspond! — Sapientia

As far as I can tell no one here or elsewhere has actually verified this. We have extracted colors of pixels through a color picker, but no one has used a spectrometer or anything.

If we were able to shoot the light through a prism, I betcha we'd get some red.

It's not about waves, photons, atoms, radiation, or whatever, "having" colour, as such. It's about wavelengths of light according with an established colour categorisation, and it's about how useful this colour categorisation is. It is useful when trying to explain what happens with certain optical illusions, for example.

Colour is not subjective, unless by colour, you just mean colour-perception. But it was you yourself who introduced that latter term, so clearly the distinction is useful, yes?

Colour is colour-perception, yes. I think that's about right, though we have to be careful here -- there are obvious traps in saying it just in this way, and in using the term 'subjective'. Color is not subjective in several senses of the word 'subjective', either, I'd say. Hence why I'd prefer to avoid using the word 'subjective' -- first-person is better, I think.

Yes, I disagree if you do. That is, I stand by my claim that optical illusions like the picture of the strawberries emphasise the fallibility of what we normally do, viz. jump to the conclusion that the strawberries are red because they appear red, and so if you disagree with that, then I disagree with your disagreement. — SapientiaWe are, but that's the point. It emphasises the fallibility in what we normally do. — Sapientia

I just mean that I think we've found where our disagreement lies. You believe that this normal way of determining color is fallible in this case. This is what I'm contending is not the case -- that the method of using a color picker on the picture to determine the color of a pixel is not a good way for determining the color of the strawberries, that our looking at the image of the strawberries is adaquate for telling us the color of the strawberries in most cases, and that it is so in this case as well.

At the weakest I'm claiming that to continue in this belief without some kind of argument about the nature of color, the brain, and reality (in the case of this image) is rational.

So what I mean is that I believe we've honed down where our disagreement is. Not that we don't disagree. -

'Panpsychism is crazy, but it’s also most probably true'You seem, on the other hand, to be suggesting that the fact that it's common justifies it. I don't agree with that. — Terrapin Station

Not that it is common, period, but rather that is a necessary part of the scientific project. Insofar that one accepts the findings of science then one must also accept some amount of creative theorizing and beliefs or thoughts 'on the limb of reason', and ask why it is they are either right or wrong. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)What about them? If I could look at the world through the eyes of a cat, I wouldn't expect to experience trichromatic vision. Just the same as I wouldn't through the eyes of a colour blind human. — apokrisis

They might look at the same wavelength energy in some sense, but we know that there is no counterfactual sensory judgement taking place, such that they see red and not green. And my argument is that experience is nothing but a concatenation of such base level acts of discrimination. Physical values have to be converted to symbolic values in which an antagonistic switching off a neural response is as telling as switching that response on. Now both 1 and 0 have meaning. Absence means as much as presence, whereas back in the real world, there is only the presence. — apokrisis

You are advocating Panpsychism it appears. For some reason the right wiring of a complex brain adds something different. The complexity of the patterns being woven lines up all the protoconsciousness to create not just bare mentality but mental content.

Yet that is still a mystical tale as the protoconsiousness remains itself rationally unexplained and beyond empirical demonstration. From a theory point of view, it is a hypothesis is not even wrong. — apokrisis

I'd say that any theory of consciousness, from that same point of view, is not even wrong. That's just where we're at. I wouldn't call this pan-psychism, though -- I'd call it (a form of) property-dualism, which seems to fit nicely in with mind-body dualism (considering that they are theories for two different questions). It would take both a third-person proto-conscious bit and a first-person proto-conscious bit to produce some qualia. (so, a rock, having no mind stuff -- let's just say -- wouldn't have qualia, nor would some dis-embodied mind, though it may be thinking of things or making computations).

I mention animals because they would, using your line of arguments against dualism, also count as counter-arguments because they will experience the world differently. What seems to me to be the case is that you believe a dualism couldn't explain deviation in experience, whereas what I'm saying is that a belief that experience is nothing but a concatenation of base level acts of discrimination couldn't explain constancy.

Here are some other things which dualism has to offer:

Explains...

the tendency towards animism.

The existence of relationships becoming de-mystified, including relationships not just with people but also with animals, plants, and objects.

How emotion flows out into the world, and vice-versa -- the inter-penetrable nature of the boundary between mind and world, and why it isn't a hard barrier.

How it is that society is characterizable as a mental phenomena, even when it isn't itself a mental phenomena.

How it is we are able to perceive the minds of others.

De-mystifies the existence of mind in the first place.

And, as I've already mentioned, dualism explains why it is that experience has so many striking regularities.

Were this a research program these would be at the end of my poster board as further areas that need research ;).

But it shouldn't be any surprise that dualism, having fallen out of favor, needs an update. That's what happens to transcendental frames as they are dropped -- they fall out of date, and the new frame is what gets updated with the new information. I just don't think that experiential deviation is enough of a reason to reject it (and, also, I'd include animals, unlike the Cartesian variety of dualism). It seems to me that, just as the strawberries here are being counted as evidence for the brain editing or adding colors, that deviations of this sort would just be examples meant to elucidate the particulars of the mind. i.e. 'needs further research' :D

I certainly agree that the self-conscious human mind is socially contructed. The ability to introspect in an egocentric way, rationalise in an explictly logical fashion, reconstruct an autobiographical past, etc, are language-based skills that we learn because they are expected of us by the cultures we get born into.

So that is part of the semiotic story. Adding a new level of code - words on top of the neurons and genes - allows for a whole new level of developmental complexity.

Qualia are perceptual qualities and so are a biological level of symbolisation. Even a chimp will experience red due to a similarity of the circuits. But only humans have the culture and language that makes it routine to be able to introspect and note the redness of redness. We can treat our brain responses as a running display which we then take a detached view of. Culture teaches us to see ourselves as selves...having ideas and impressions.

So the point then about the red strawberries is that there is also still the actual biological response that can't be changed just by talking about it differently. And this shows that the biological brain itself is already a kind of rationalising filter. We never see the physical energies of the world in any direct sense. The world has been transformed into some yes/no set of perceptual judgements from the outset. It is already a play of signs. And so the feeling of what it is like to be seeing red is somehow just as much a sign relatiion as the word "red" we might use to talk about it with other people.

If you are a physicalist, you want to somehow make redness a mental substance - a psychic ink. And if we are talking about colour speech, we are quite happy that this is simply a referential way of coordinating social activity or group understanding. The leap is to see perceptual level experience as also sign activity - a concatenation of judgements - not some faux material stuff. — apokrisis

Something I'm not quite following here is how you escape the charge of representationalism. Or perhaps this is just something I thought you were trying to say, but aren't? If red is a sign, then it does seem that the mind is representational at least. (at least, as I understand sign -- a signifier and a signified, a mark and a mental-thing-ish-semantic-bit fused together)

Just asking for clarification here.

The mind is a modelling relation with the world. And after all, it should feel like something to be in that kind of intimate functional relation, right?

I don't think so, per se. At least, if we are physicalists. If not, then it seems that red could serve just as well as blue, as the inverted-spectrum argument goes -- and, in fact, if it's just a large functional organic-machine, that wavelengths are just as good as red-ness because that's still information, a pre-sign informational bit which can be converted into an electrical-voltage-sign which enters the dynamic system known as the brain, which sends out its signals to the body to reproduce.

But one need not feel anything in this process for reproduction to occur. All that would be needed is for information to be fed into the functions which generate signals which form the basis of signs. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)The logic remains - if dualism is true and qualia are not brain dependent, then the blind should have at least imaginative access to those qualia, despite eyes that have never functioned in a way that would produce the right neural circuits. And you shouldn't be able to zap the V4 colour centre of the brain and produce then a loss of colour qualia as a consequence. — apokrisis

I'm not so sure about that. What about other creatures? Non-controversial examples of other creatures which have vision and demonstrate intelligent behavior I mean. It seems to me if your reasoning holds then any deviation whatsoever should disprove dualism. But why would I want to defend something which is so clearly and easily refutable by a wealth of counter-examples?

I mentioned color-blindness before, and I'll mention it again. It seems to me that the color-blind look at the same red in a different way. I don't think that perception necessarily displays every aspect of the world.

For the congenitally blind I could see it going either way. Wouldn't it depend on exactly which side of the divide the qualia are on, for example? And why can't qualia only be perceived if one has both the right mind-stuff and the right body-stuff? What if the perception of qualia just is two proto-conscious bits on each side of the divide lining up?

Perception doesn't have to be veridical and univocal for dualism -- dualism would just explain the apparent similarities of experience, since there would be a shared structure of mind.

Besides, I am mentioning this only to show the weakness in transcendental argumentation -- it's valid, but it's far from certain. Often enough what ends up happening is that counter-examples get counted as support in one theory, and vice-versa. The counter-examples just take on a different m

eaning depending on which transcendental conditions we decide are more likely.

And one man's modus ponens is another's modus tollens, after all ;).

It'd be less confusing to say we prejudge on the whole. And still less confusing to say we positively predict. Conceptions are schemata, to make use of the good old fashioned cogsci borrowing from Kant. We have mental templates to which the world is already generally assimilated. Post hoc judgement is reserved then for where the schema prove to need tailoring. — apokrisis

Sounds good to me. I agree with this general notion of cognition, then, let's say?

I still think it is ratio-centric, but I don't think ratio-centric thinking has to be somehow directed by an individual -- it can all take place 'under the hood' of awareness.

Seems we are good here to me. The only thing I'm questioning is whether this under-the-hood cognition is what results in the structure of experience. It seems to me that it's more a learned habit, something taught by the environment, something which can be trained and honed for, but likewise, can be diminished and taken apart.

So rather than it being a model of either the mind or experience, it's just something the mind can do, and it's just a part of what shapes our awareness of experience.

Hope that helps.

The way you phrase this again says you find it natural to think about the mind as representational - the cogsci paradigm which is being replaced by the enactive or ecological turn in psychology (or return, if we are talking gestalt dynamics and even the founding psychophysicists). — apokrisis

I think we'd have to think of the mind as representational if we believe that in reality the strawberry we see is gray, while in appearance it is red -- at least to some extent. Here I'm just trying to engage the argument as it is presented, not necessarily endorsing this view of things. As I noted to Sapientia, I don't think this distinction is very useful to perception, but there has to be some engagement at some level otherwise we'll just end up talking past one another, it seems to me.

And that is my point about the paradigm shift represented by semiotics. Representationalism presumes that a stable reality can be stability pictured and so stabily experienced - begging a whole lot of questions about what could ever be the point of there being the observer essentially doing nothing but sitting and staring at a flickering parade of qualia painted like shadows on the cave wall.

But give that observer a job I say. Observation - defined in the general fashion of semiosis - is all about stabilising the critically unstable. So minds exist to give determination to the inherent uncertainty of the material world. If matter is a lump of clay, minds are there to shape it for some purpose.

And uncomfortable though it may seem, the science of quantum theory says observers are needed to "collapse" the inherent uncertainty of material nature all the way down. Existence is pan-semiotic.

Somehow we now have to honour that empirical fact in a way that makes Metaphysical sense. Most folk agree we can't claim that "consciousness" solved the quantum observer problem. But quantum foundationalism does think that some notion of information, contextualism and counterfactuality will do so - which is another way of talking about semiotics.

So I'm talking about a sweeping paradigm shift. The systems view is about how existence has to founded on the primal dynamism of material uncertainty becoming regulated by the sedimentation of informational constraints.

Heraclitus summed up the understanding already present in Greek metaphysics - existence is flux and logos in interaction.

And the mathematical exploration of what that could mean is still being cashed out, as with the return of bootstrap metaphysics in fundamental theory - https://www.quantamagazine.org/20170223-bootstrap-geometry-theory-space/ — apokrisis

Sounds neat to me. I don't endorse a representational view of mind, personally. But I'm also uncertain to what extent mind even actually overlaps with experience, personally. I sometimes get to thinking that experience is sort of its own thing -- and that our minds are first collective, and second individual -- there is a pre-existing mind to our birth, one generated by the social interactions of our peoples (sort of like distributed cognition and extended mind, as one could conceive of the scientific project, but less structured or intentional or teleological), which in turn generates our sense of self (usually through a mixture institutions -- the family, the church, school, work), and an individual contact with this more general structure. This individual contact and sense of self is what combines to form our personal mind, which in turn is what directs awareness, but does not generate experience. Rather, it directs awareness of said experience. Or perhaps at this point we could be said to have some agency in the affair and could claim we direct our awareness of experience, if only in part.

But the mind thing isn't making model things of the experience things, so it's not representational. Rather, there's a kind of flow or seepage between the two

Just laying that out there to make some of my statements clear. It's worthwhile to explore the arguments because my notions are quite hazy, merely intuitive, un-argued for, and not really worth considering and certainly not ready to be lain out in argument or for persuasion, and only worth mentioning to make my other statements in this discussion clear. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)So by your dualistic reasoning, every congenitally blind person ought to report imagining colours, every congenitally deaf person would still imagine noises, every teetotaller would still know the feeling of drunkenness, etc. After alll, something may be missing in terms of inputs to drive brain activity but we all partake in the one mind substance, right? — apokrisis

Not necessarily. Cognition of mental phenomena could depend upon physical inputs, after all -- and then, also, just because there is a single-mind that does not then mean that we are all one. The identity of a person -- from their physical body up -- is constructed out of the raw stuffs of the world. One mind-world -- multiple people within the mind-world.

Brains are salient to individual identities in such a world, so it's not entirely off base to be looking at brains -- that would be one part of the physical-world, after all -- it's just not the whole picture, in accordance with this line of reasoning.

So what does your "judgement" entail as a neurological concept? It does seem to imply a hard dualism of observer and observables. It does give primacy to acts of attentive deliberation where I am pointing out how much is being done automatically and habitually, leaving attention and puzzlement as little to do as is possible. So talk of judgement puts the emphasis in all the wrong places from my anticipatory modelling point of view. Just the fact that judgements follow the acts strikes another bum note if the impressions of present have already been generally conceived in the moment just prior. — apokrisis

Hrrmm, I wouldn't disagree with much of judgment being on "auto-pilot", actually. One can consciously judge, of course, but judgment is just the application of concepts to particulars, or the powers of the mind. That doesn't mean it has to be something I consciously do. It just means that the mind is a disciminating-machine, marking differences on the basis of concepts. Actually, your description of visual perception is pretty much what I mean by judgment -- the ganglion, to use the brain-theory of the mind, is judging the light coming in, and is already discriminating from the beginning.

I can see how such language could be confusing. I'd say that while we can pause to consciously consider and judge our mental processes, that the majority of the time they are beyond awareness and not thought too much about -- so, while I'm doing my thing, or focusing on this or that, my mind is judging, i.e., discriminating between particulars, making distinctions (or recalling distinctions learned, also often subconsciously, to further judge/discriminate between particulars and make sense out of what is just too much to take in total while still making sense)

On this front I don't think we have much to disagree on, to tell the truth. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)I really don't think that the brain is "adding colors". I think that's a mistake, thinking that the brain is adding red. I believe the red is there, as part of the mixture within the grey. I would say that the brain "subtracts" or otherwise tries to account for the teal, because it appears like there is a lens of teal between the eyes and the strawberries. So the teal is subtracted from the grey, and we can see the red within the grey. — Metaphysician Undercover

I believe that the strawberry-image in the picture is red. But what that says about this or that theory of color or perception, I'm less committed on. I really don't know what I believe there -- I'm just following the arguments where they go. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)No, the brain doesn't drop out of the explanation. And it doesn't need to be a natural object outside, so that criticism is based on a false premise that was never part of my argument. — Sapientia

I think we're miscommunicating a bit here. To be fair, your argument was a google search. What I mean by 'drops out of the explanation' is that all that is said is we have reality on one side, and appearance on the other, and two claims about both. When asked how reality becomes appearance, the answer is 'the brain did it, just like it does with other objects to keep the color constant under different light conditions' where the main example was a blue sky.

My question is -- what does the brain do to reality to make the appearance? But the answer is "it makes the appearance appear like the appearance appears, different from reality" -- which just masks the mechanism I'm asking after.

And I'm not the one misinterpreting the grey strawberries as red, that's what you're doing. That's the common misinterpretation that is shown to be erroneous, and to which you're clinging, despite the scientific evidence to the contrary.

With science. What you describe above determines appearance. You can conflate that with something else, but that would be erroneous/misleading.

I'm grouping these just as a side note, because it will take us pretty far astray.

A basic view of science:

Science is little more than a collection of arguments about certain topics. There are established procedures in place for certain sorts of questions, there are established beliefs due to said process, but in the end it's a collection of arguments about certain topics on what is true with respect to those topics.

At least, as I see it. We don't science it -- we make an argument. An argument, in this context, can of course include experimental evidence. But said evidence must, itself, be interpreted to make sense.

So really I'm just asking after the arguments in play. What does the scientist say to make his case convincing to yourself? What convinced you?

I've already addressed those first two sentences. They are irrelevant, since that don't support your conclusion. I accept both of them, yet reach a different conclusion. — Sapientia

I think this is addressed later in your posts.

And I doubt your last sentence. What do you mean by that? — Sapientia

I mean that when Newton placed prisms to diffract light from the sun into a spectrum that the red part of the spectrum which came out of the prism was called 'red' not because it was had a larger wavelength and such was proven, but rather because the light was red.

If all of the parts are made of wood, then the chair is made of wood. Do you disagree? — Sapientia

No, that makes sense to me.

Though if all the parts are made of wood, and some parts are painted green while others are painted yellow, then it wouldn't make sense to say that the chair is green. :D

In fact, what if the chair had a sticky reprint of the pixel-image we're discussing? Just to make it closer. Then, what color would the chair be?

Although if you're confused about appearance and reality, you might think otherwise. — Sapientia

I'm thinking this is probably where we diverge the most, then. We seem to be in agreement on both the fallacy of composition and whether or not it has merit depends on the circumstances. If, in fact, the image is gray and appears red then certainly I am wrong.

So really it seems we're more in disagreement on determining which color is the real color, and which color is the apparent color.

Okay. But if we're saying that wavelengths or whatever are real - which is the assumption that I'm working under, and which will be agreeable to many - and if we're talking about colour in terms of wavelength or some related scientific description, then it makes sense to say that what we're talking about in such cases is reality. And similarly, with regards to any appearance which seemingly conflicts with this reality, if we're categorising that in contrary terms, then it'd make sense to say that this is not real. Furthermore, if we're attributing properties, and we accept the aforementioned, then we should do so accordingly in the right way, by attributing appearance to the subjective and property to the objective, rather than attributing appearance to the objective, as some people in this discussion seem to be doing by making certain kinds of statements which lack clarity and precision. — Sapientia

Cool. This is much closer to what I'm asking after.

I think this condition: " if we're talking about colour in terms of wavelength or some related scientific description,"

is likely the culprit of disagreement. Electromagnetic waves are real, as far as anything in science goes. But photons, nor atoms, have any color whatsoever. This is not an attribute of the individual parts of what we are saying causes the perception of color. Certain (regular, obviously, as you note about gray not being a regular wave) wavelengths of light correspond with our color-perceptions. But the color is not the electromagnetic radiation.

Color is -- to use your terminology -- subjective. I'd prefer to call it a first-person attribute not attributable to our physics of light, which is a third-person description of the phenomena of light rather than objective/subjective, myself.

Okay, I don't have a problem with that epistemic approach, but it does seem naive to end up with that common means of determination which has been demonstrated to be erroneous in at least some cases, as with the strawberries. — Sapientia

Cool. Then I think we're more or less on the same page in terms of the terms, at least :D

Whether such and such a demonstration is erroneous seems to be the major point of disagreement.

I don't think we need to get caught up in the so-called hard problem here, if that's what you're getting at.

Responding to this in reverse order because I think the latter point is more important:

I don't think we need to get caught up in the hard problem either. I wasn't really trying to go there, but it does seem related to the topic at hand. But it seems like we've managed to pair down our disagreement to one of "how to determine such and such", so there's no need to get into it.

We become conscious of certain things as a result of our respective brains. We see the grey strawberries as red, and, typically, our initial reaction is to think that they are in fact red. — Sapientia

Honestly, while brains are certainly a part of the picture of human consciousness -- I wouldn't dispute this -- we just don't know how we become conscious. Either there is no such thing in the first place, in which case there is nothing to explain, or if there is such a thing then we don't know how or why it's there.

We are, but that's the point. It emphasises the fallibility in what we normally do. — Sapientia

I think this is covered at this point. Let me know if you disagree. -

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)I'm off to work. I'll get reading and replying this evening.

-

What Colour Are The Strawberries? (The Problem Of Perception)Kant is a familiar reference point. But my argument is more properly Peircean or biosemiotic. — apokrisis

Cool.

Of course we can't compare our experiences to know that your red is my red. in that final analysis, there is a brute lack of counterfactuality that thus winds up in an explanatory gap. But quite a lot of telling comparisons can be made on the way to that ultimate impasse. So for instance everyone sees yellow as the brightest hue, and also doesn't see brown as the blackish yellow it really is. And that phenomenological commonality is explained in complete fashion by the known (rather jury-built) neurological detail of the visual pathways.

So in the end, our yellows might indeed be different as experiences. Yet we can track the story right down towards this final question mark and find that similar neuroscience is creating similar mental outcomes. Thus we are not getting a strong reason for the kind of doubt - the talk of the purely accidental - that you might want to introduce to motivate a philosophy of mind argument. — apokrisis

Hrmm, not purely accidental I wouldn't think, but accidental. Some people's judgments happen to align, after all -- one could think there is regularity to be found based on some grouping. But as judgments differ from various persons as we can observe by means of the behaviors which are the results of judgment, and color is an experience of judgment, it wouldn't be a function of mere doubting but rather a fair inference from our explanatory frame that we do, in fact, see different colors. If what we are saying is true about color, then there is no explanatory gap -- it is the most sensible thing to believe. (though it does bugger the more functionalist notion of the brain which seems predominant -- at least on its face)

There's another reason why similar neuroscience could be creating similar mental outcomes -- the other flaw of Kant's philosophy, which whether we are Kantian or not these sorts of arguments do seem to follow this form of argumentation, is the transcendental argument.

So we have a gray image with a particular teal chosen to make the gray strawberries red. This is after having asked what are the possible conditions of experience -- the experience being this notion of color constancy. The brain adding colors to appear constant is the necessary conditions for colors remaining constant, or in this case, not doing so. We see that colors are constant(generally) and modified(when exploited) in experience, therefore this precondition is necessary.

But we can come up with other possible pre-conditions which explain the pheneomena. As a for instance, we might say that it is not the brain which judges and adds colors to experience, but the mind which does so. We know this to be so because we actually do see the same colors -- at least the same hues (as you note, yellow is the brightest hue for all of us). This explains the seeming regularity of experience better than reference to an embodied organ which differs from person to person. This organ, like the heart and the lungs and the skin, is certainly necessary for mental activity. Modifying it modifies mental activity. But it is not the best explanation for experience (one way of parsing the transcendental argument is that it's kind of the pre-cursor or model to abduction, hence my use of the term 'best explanation')

However, if we all agree to the same pre-conditions, then all the phenomena start becoming support for the pre-condition -- when, in fact, the pre-condition was meant to explain the phenomena. So this would be another reason why similar neuroscience could be creating similar mental outcomes -- mere agreement on the proper pre-conditions for such and such phenomena.

I'm trying to be quite clear that talk of emergence is very much reductionist handwaving most of the time. It is taking the idea of physical phase transitions - the idea of properties like liquidity emerging as a collective behaviour at some critical energy scale - and treating consciousness as just another material change of that kind.

But I am arguing the exact opposite. I am saying there is a genuine "duality" in play. The brain is a semiotic organ and so it is all about a modelling relation based on the play of "unphysical" signs. So material physics isn't even seeing what is going on. No amount of such physics could ever produce anything like what the brain actually does by just adding more of the same and relying on some kind of collective magic.

Of course physics does self organise and that kind of emergence is a really important correction to physicalist ontology. But semiosis is yet another story on top of that again. — apokrisis

OK, cool. We are definitely in agreement here. Though my doubts in emergence were more produced by seeing how arguments for emergence fall to all the same arguments against dualism (in particular the argument about how these two planes interact -- emergence is very hand-wavey on this front, moreso than even the early pituitary-gland positing dualists ;)). And since most emergentists were anti-dualists, it just seemed an inconsistent position since emergence is mostly motivated by trying to find a non-dualist solution to the mind-body problem.

Ah well. Forget any mention of Kant then. — apokrisis

Cool. Though I'm not sure that K's theory of truth was at issue here as much as his theory of cognition which seems to be in play.

This is Peirce so "truth" is pragmatic. We have already shifted from requiring that the world be represented in some veridical fashion. We are now viewing cognition in the way modern neuroscience would recognise - modelling that is ecologically situated, coding which is sparse, perception that is only interested in the degree to which uncertainty can be pragmatically minimised.

Why does the eye only have three "colour" pigments when evolution could have given us as many as we liked? Less is more if you already have in mind the few critical things you need to be watching out for.

Seems to me this is difficult to explain along evolutionary lines, at least immediately, because the way our species happens to see differs from the way other successful species happen to see. Also, while vision has evolutionary advantages for a land-dwelling species in an environment flooded with light -- or I can see how that makes sense at least - that doesn't mean that the three-color vision we experience is evolutionarily related. It could have been a bi-color, for all we can tell, and the tri-color vision just came along for the ride, or was sexually selected for, or was a random mutation and a seismic event wiped out those with bi-color vision.

It's all rather speculative, no?

Neuroscience has a ton of more technical jargon. But it is a basic fact of neural design that every neuron has hundreds of times more connections feeding down from on high than it has inputs coming up from "the real world". So just looking at that anatomy tells you that your prevailing state of intention, expectation and memory has the upper hand in determining what you wind up thinking you are seeing.

If you know pretty much exactly what should happen in the next instant, you can pretty much ignore everything as it does happen a split second later. And thus you also become exquisitely attuned to any failures of the said state of prediction. You know what requires attentive effort in the next split second - the hasty reorientation of your conceptions that then, with luck, allow you to ignore completely what does happen after that as you have managed now to predict it was going to be the case.

So yes. This doesn't tally with the usual notions of how the mind should work. But that is because the phenomenology as we focus on it is naturally about all our constant failures to get predictions right. It seems that the homuncular "I" is always chasing the elusive truth of an ever surprising reality. However that introspective view by definition is only seeing things that way because there is such a bulk of events successfully discounted in every passing instant.

For example, in the second that just passed, I was effectively, subconsciously, predicting that Donald Trump was not about to barge into my room, an asteroid was not about to plough into the park outside my window, my foot wasn't about to explode in a shower of fireworks. So that is what brains do - allow us to discount a near infinite ensemble of possibilities as that which is almost infinitely unlikely.