-

Nature versus NurtureThe point is that it is one thing to claim something is genetic or nature and another thing to have isolated and treated a cause. Maybe there are strong genetic causes to family dysfunction? — Andrew4Handel

Maybe they are. But gene expression is far more complex than you make it out to be - in fact, it's not at all the case that simply saying something is 'genetic' automatically situates it on the side of 'nature'. Both MindForged and DiegoT have already mentioned just how implicated the very idea of 'genes' are with the cultural and social environment in which they belong. It simply an obscene simplification to align genes with nature to begin with. It is no accident in fact that some authors have called into question the very idea of a gene as a causal agent unto itself, precisely given the complexity of their expression. Again, this attempt to put things into little boxes labelled 'nature' and 'nature' is nothing but oversimplification that would make for worse policy crafting, not better. -

Nature versus NurtureI have never heard of a non medical intervention into someones life or family where genes have been mentioned. You do not have to explicitly say nurture but it is clear that most interventions outside of genetic illnesses are nurture interventions and the intervention is not based on any knowledge of the peoples involved genetic traits. — Andrew4Handel

This is not an argument. This is barely an anecdote. Nothing doing. -

Nature versus NurtureSure, there are reasons to find 'causes' for things and attempt to intervene; one wonders what good it does to place those causes into little pre-marked boxes labelled 'nature' and 'nurture'. If anything, such an artificial parsing of phenomena would prejudice an investigation, not facilitate it. The world doesn't care about whatever concocted categories we'd like to make for it.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.So two roles, one linguistic and one practical, that come together to form a language game. The game is where the language makes contact with the world.

Is that about right for you? — Banno

Hmm, but it's all linguistic. And all practical. Language is always-already in contact with the world: it is worldy qua activity - qua practice. -

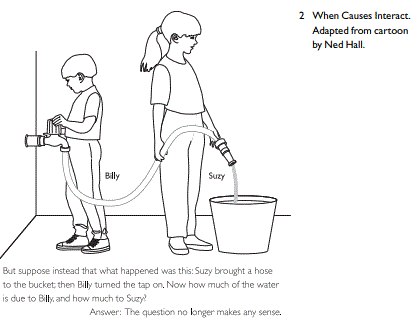

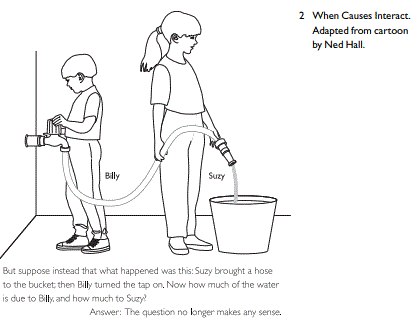

Nature versus NurtureOne of my favourite images from Evelyn Fox Keller's The Mirage of a Space Between Nature and Nurture:

-

Nature versus NurtureI think the idea that nature and nurture play an equal rule is vague — Andrew4Handel

I didn't say they play an equal role. I said the whole debate is largely meaningless. -

Nature versus NurtureThis is a false dichotomy, read up on epigenetics. — MindForged

Yep. Anyone who thinks there is an agonistic relation between nature and nurture is uninformed about both. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Side note: the meter rule discussion has some really interesting parallels with the discussion that opens On Certainty, where Witty similarly trashes the idea of either assenting or denying a certain kind of statement:

OC §10: "I know that a sick man is lying here? Nonsense! I am sitting at his bedside, I am looking attentively into his face . -So I don't know, then, that there is a sick man lying here? Neither the question nor the assertion makes sense. Any more than the assertion "I am here", which I might yet use at any moment, if suitable occasion presented itself."

It would be a cool exercise to trace the connections between these two lines of thought, but that'd be for another thread.

Also, I had a thread on here a while back about the meter, although approached from a very different angle, if it might interest anyone to read: https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/1114/the-example-or-wittgensteins-undecidable-meter (please don't reply to it, it'd be zombieing a very dead thread). -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§50 (Part 2)

Witty's reflections on the meter rule in Paris have been the cause for alot of confusion, but I think alot can be cleared up by simply placing the comments in context: Witty's revision of the themes in the Theaetatus passage. Let's first recall §49, where Witty grants that (something that grammatically counts as) a simple plays no explanatory/descriptive role: such a grammatical element can only named, and to name something, is not to explain anything. Next, recall his further point that "naming and describing do not stand on the same level", and that naming prepares the way for describing.

Now, if one treats the meter rule as having the same role as a name, the comment becomes relatively clear: the meter rule in Paris is that which 'explains' what counts as a meter (it is a means of representation), and is not something that is itself to be 'explained' (is not something that is represented). Witty makes this particular connection explicit:

§50: "The same applies to an element in language-game (§48) when we give it a name by uttering the word “R” - in so doing we have given that object a role in our language-game; it is now a means of representation".

There are at least two interesting points to make here. The first has to do with the disparateness of the examples, and what unites them. Consider: what allows Witty to analogize between a physical object (a metal rod in Paris), and a kind of word (name)? - Two seemingly very different things. Well, what they share is a role in a particular game - a 'game of measuring' in one, as Witty says, and a 'language-game' in another. It is the role of each element in the game particular to it that allows that element to carry the burden of explanatory work.

Unlike a Socrates, who would attribute to each element an ontological standing, having to do with it's being-a-simple tout court, Witty attributes to each only a relative grammatical standing, whose role in explanation is derivative or parasitic upon our use-in-a-game. Here, once again, is the substation of ontology for grammar that I mentioned in previous post: language-games as a condition of sense, including the sense of existence itself, which is here sucked dry of it's metaphysical grandeur and indexed simply to... grammar:

§50: "And to say “If it did not exist, it could have no name” is to say as much and as little as: if this thing did not exist, we could not use it in our language-game".

The second thing I want to make explicit is that the fact that elements can have roles also implies the contingency of those roles. A word can play one role in one instance, and another role in the next; the metal rod in Paris might be replaced down the line and no longer be the paradigmatic meter: in both cases neither the word nor the rod changes 'in itself' - only its role. So not only do roles relativize what can be said of a particular thing (were the rod in Paris just any other ordinary rod, presumably we could ask whether it were a meter or not), but so too can roles themselves change (the paradigmatic rod in Paris may become just another rod). Ontology is here doubly 'de-substantialized'.

(Finally, note that this mirrors again the discussion in §49 which comments on how words and sentences (simple and complexes) can change roles "depending on the situation in which it is uttered or written"). -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.I wasn't satisfied with it. Tweaking it a bit before reposting :)

-

Why do we hate our ancestors?that they might even be people like you or me. — TogetherTurtle

Speak for yourself. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Or posts even! In this thread! About the book! :gasp:

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Just to be clear - the PI for me is... well put it this way, it's one of two books I've ever annotated from start to finish, so yeah, I kinda know that you're jumping ahead. Water's wet, you'll tell me next?

My approach here is to simply read it as if for the first time, taking each passage as it comes, and reading it organically. These groups are best suited to first time readers, so that's the assumption I'm operating under. If I'm not dealing with things that are dealt with far later in the text, then yes, that's almost exactly the point (did I need to explain this? To which idiot?). If and when I do refer to later sections, it's something I try to signpost pretty heavily

Feel free to do otherwise if you'd like. But my plan is to stick to the same parameters of reading that I've followed so far. Which includes dealing with replies, objections, or other derivitive discussions. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§50 (Part 1)

§50 continues its engagements with the Theaetetus passage, this time, turning its attention to the question of existence (or ‘being’). Before going on it’s worth quickly noting just how much Witty has so far excavated from this passage: first, in §47 and §48, the relation between simples and composites; next, in §49, the role that both have with respect to explanation, description, and naming. Now, in §50, the question of the meaning of ‘existence’ with respect to simples and composites. All these terms and the relations between them - explanation, description, naming, existence, simples and composites - can all be found in the Theaetetus passage, and its actually pretty cool to see how much Witty manages to wring out of it in his own efforts to establish an alternative articulation between them.

Anyway, §50 pulls all these threads together and is, as a result, probably one of the more confusing if not brilliant passages in all of the PI. In it, Witty fleshes out the notion - one I mentioned earlier - that language-games are the condition of sense, this time, by paying close attention to the sense (and thus grammar) of ‘existence’. For existence too has a sense, and its sense is similarly conditioned by the use to which it is put. Hence the first part of §50, which begins by setting out a conditional (an ‘if’), which lays out a use of ‘being’ and ‘non-being’, and follows its consequences:

§50: “If everything that we call “being” and “non-being” consists in the obtaining and non-obtaining of connections between elements, [then] it makes no sense to speak of the being (non-being) of an element” (emphasis and ‘then’ added).

With what follows being simply the counterpart of this conditional (I’ll re-arrange the sentence to make it more obvious):

§50: “If everything that we call “destruction” lies in the separation of elements … [then] it makes no sense to speak of the destruction of an element” (emphasis and ‘then’ added).

As with the grammatical relativisation of the simple and the complex in §47 and §48, here too the sense of ‘existence’ is made relative to grammar, or, what amounts to the same thing, our use of words in a language-game. The conditional serves to highlight that "everything that we call “being” and “non-being” may well be otherwise; that is, contingent upon other grammars or uses of words. The second part of §50 brings the question of names back into the fold, and deals with one of my favourite bits in the PI, about the meter rule in Paris. It gets its own post. -

I can't post a replyHi, your reply got caught by the spam filter, probably because you didn't add any paragraph breaks, so it's all just one wall of text - which is something spam bots sometimes do. In future, please just add some paragraphs to your posts otherwise it'll get caught again. Your reply is there now. I've added some paragraphs, but I'd really prefer not to do it again.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Of course it's idiosyncratic. This is philosophy. The OED is for children who are too inexperienced to pay attention to context.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Ah, but did Witty have daddy issues? Can't read the PI without knowing that either.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.See my response to StreetlightX above, basically I think its a mistake to treat it as a book about language in any academic sense — Ciaran

Says someone who reckons it's important if Witty correctly represented Augustine? And I'm accused of being too academic? Cute. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Eh, who cares whether Witty got Augustine right, or if it really does represent some commonly held view. Augustine is a foil to develop a point, and can be treated as that without loss. Irrelavent point.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.I do not think that Witty has used that term though — Metaphysician Undercover

It was discussed when we went over §29, and the boxed note after §35, where the term was employed. In any case, I've made clear my use of the term in my own discussions of those passages, so I'd prefer you didn't mistake your short memory for a lack of fidelity on my part. And who cares what preconceived notions you bring to the table? As with your initial confusion about 'games', they were irrelevant then, and they remain irrelevant now. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.That's correct, and the point being, yours and Sam's discussion of grammar is out of place, not relevant to the text, and actually quite distractive. — Metaphysician Undercover

But Witty has talked about grammar. We've talked about grammar. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.It's a reading group dude. We read the PI as we go. It's pretty simple.

-

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Grammar involves rules, and we have not gotten to the point where he discusses what learning a rule consists of. — Metaphysician Undercover

At this point, Witty has nowhere linked grammar with rules (not saying there aren't any, but you're preempting, so your objection doesn't make sense).

Streetlight has done a pretty good job for not having much of a background in Wittgenstein (if I understood his earlier comment correctly), but this is probably due to his philosophical background. — Sam26

Cheers but I've been reading Wittgenstein on and off for years. Never quite in such depth, so this is a nice opportunity to hash out the PI in ways I've not done before.

StreetlightX is doing a bloody fantastic job delving into the material with a sharp intellect at a great pace — John Doe

Heh, I'm basically doing one subsection a night, and at this rate, it ought to take about two years or so lol. But hopefully not every section will demand commentary. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§49

I'm skipping §48 because it's fairly self-explanatory [no natural way to decide on a simple], but also because the later sections that return to it actually hold the more interesting discussions of the example that it offers. We'll take it up as those discussions crop up.

§49 (and §50!) return to the curious invocation of explanation in the Theaetetus passage quoted in §47. If we recall, there Socrates says that so-called primary elements cannot be explained, insofar as they themselves carry out explanatory work. Explanation is a one-way street, from simples, to composites. However, having 'grammatically relativized' (if we can call it that) what counts as a simple and a composite in §47 and §48, §49 now explores the consequences that this relativization has upon this apparent one-way street.

The consequences are as one would expect: Witty grants that if something counts as a simple in a particular use of langauge, then Socrates is right: the (grammatical) simple cannot be something that describes, insofar as it is only named (names do not describe). However, what are simples in one instance may be complexes in other instances: this is what Witty is getting at when he says that:

§49: "A sign “R” or “B”, etc., may sometimes be a word and sometimes a sentence. But whether it ‘is a word or a sentence’ depends on the situation in which it is uttered or written".

- where 'words' correspond to simples, and 'sentences', to composites. Two examples are given. The first in which someone is trying to describe the complex colored squares of §48 (in order to reconstruct it, say), wherein to speak of "R" is to have "R" function in an explanatory role (An imaginary conversation: Q: "What squares are in positions 1, 2, and 7?"; A: "R"). In this case, "R" describes - it plays an explanatory role. In the second case, one is trying to memorize what exactly is designated (named) by "R" in the first place ("That is 'R'"). In this case, R is not something that explains, but simply names.

One point of interest here is that §49 answers a question posed back in §26, where Witty writes that "One can call [naming] a preparation for the use of a word. But what is it a preparation for?". It's here, in §49, that Witty answers this question: "Naming is a preparation for describing".

As usual, Witty is once again paying close attention to the types of uses of words, without which one can fall into "philosophical superstition", as he calls it here. Such superstitions being, again, the confusion between kinds of uses of words. Here we can see a bit better why such confusions happen: precisely because the role that a word can play is reversible: in one case a simple, in one case a composite, in one case a name, in one case a description - all depending "on the situation in which it is uttered or written". -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§47 (Exegesis)

Following §46, in which the question of the simple and the complex was bound up with questions of existence in Socrates, §47 will begin the process of substituting ontology for grammar: questions about existence for questions about uses of words. It begins with a rhetorical question that, tellingly, once again asks about the composition of ‘reality’:

§47: "But what are the simple constituent parts of which reality is composed?” (my emphasis).

To this question, Wittgenstein will reply that we can only make sense of the notions of the simple and the composite by reference to how the word(s) in question are put to use - and further, that there innumerable ways in which they can be put to use:

§47: “The question … makes good sense if it is already established … which particular use of this word is in question. If it had been laid down… then the question … would have a clear sense - a clear use”.

Note here that use and sense are almost used as synonyms: to have a sense - to mean something - is to have a use (in a language-game…). The idea is that it is only once we have sorted out the particular grammar of our use of terms, that we can begin to make sense of the very question of the simple and the composite: getting the grammar right is a condition of making sense of the question, and subsequently, of being able to provide an answer. All this can be paraphrased by saying, as Witty kinda does, that one cannot make sense “outside a particular [language] game”: language-games act as conditions of sense.

§47 (Remark: Relation Between Language and World)

Here is where I think things actually get super interesting, from an epistemological point of view: if grammar is a condition of sense, and there are innumerable ways in which we can employ grammar(s), what exactly is the status of grammar (hence language and sense) itself? For it’s clear that grammar cannot be ‘read off’ the ‘thing itself’: the chess-board in all its black and white glory provides no definitive answer - cannot provide any definitive answer - as to how to parse what is simple and what is composite about it. The grammar of our languages(s) do not 'naturally mirror' the structure of the world (if it even makes sense to speak of a 'structure' of the world).

This, again, is because sense is function of our use of words. This is one way to understand Witty's objection to 'philosophy'. 'Philosophy', Witty thinks, tries to read sense directly off the world itself as though some kind of mirroring relation: it doesn't pay enough attention to the mediating role of grammar in conditioning sense (hence the closing remark of §47, which derides the 'philosophical question' by 'rejecting' it).

Now, there are a few directions and conclusions one can draw from this line of thought, but one I'd like to nominate is what I might call the relative autonomy of language (or, on the flipside, the indifference of the real (to language)): the act(s) of making sense are relative - and can only be relative - to the concerns and interests that we have as users of language - our forms-of-life, without which we would not make sense. Another way to put this is that meaning must be made, and not merely 'found': it involves an active process of construction, which is constrained by, but not entirely determined by, the reality of which it (sometimes) speaks. This needs to be made more precise, but I make these quick remarks as extrapolations from the text so far, to indicate at least the spirit in which I read these sections, if not the letter. Also worth keeping this in mind for the sections on aspect-seeing later on in the text. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§46

So, like I said, §46 marks a change in the argumentative strategy of the PI, with Witty no longer looking at types of uses of words, but rather, more closely at what are considered 'words' - what is it that are 'used'? He begins with a passage from the Theaetetus, which is actually pretty damn complex. We can break it down like this:

For Socrates, to each so-called primary element corresponds a name (there is a one-to-one mapping between name and primary element). Names however, do nothing but 'signify' primary elements: they tell us nothing about them other than that they exist or not. Now, it is important here that primary elements and their names are associated with existence. They are ontological primitives.

Importantly, one cannot give an explanatory account of these primitives, because these primitives are what do any kind of explaining. It is only when primitives are composed together, that we can have 'explanatory language', language that does more than just name, and hence, determine a thing's existence. I bring to the fore here the question of existence, because the remarks that follow will contest not only what counts as a complex and a simple (which is what is often focused upon), but far more importantly, the very status of complexes and simples as ontological. In place of ontology, Witty will substitute grammar. We'll see what this means as we continue. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Orienting Remarks for §46 Onwards

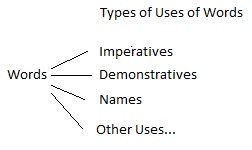

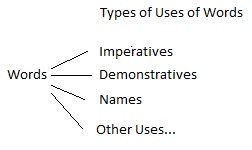

§46 marks yet another turn in the argument of the PI, and probably the most radical so far. Up to now, it can be said that Witty's concern has been to establish that there can be different kinds of uses of words (and not just one kind - naming, as with Augustine). That is, it's not just that different words have different meanings (as if words merely differed by 'degree'), but that the meanings of words also differ in kind: we can distinguish between types of words (with Witty so far having examined, roughly in order, imperatives, demonstratives, and names). Diagrammatically, we might be able to put it this way, with the right hand side of the diagram being what has been covered so far:

§46 onwards turns its attention to the left hand side of this diagram. So far, the question of exactly what is subject to different kinds of use hasn't really been brought up, other than saying that it is 'words' which have different kinds of use. In fact, the examples offered by Witty so far have themselves largely been individual words like 'slab!' or 'Nothung'. It is this assumption that is here put into question in the discussion after §46. The question could be put like this: what is the 'unit' of meaning? It is a word? A sentence? A proposition? In fact, is it legitimate at all to speak of a unit of meaning? And if it is, under what conditions?

This concern can actually goes all the way back to §1 where Witty already signposted his intention. To recall:

§1: "In [Augustine's] picture of language we find the roots of the following idea: Every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated with the word. It is the object for which the word stands."

As I mentioned earlier in my commentary on this line, I said that Witty will try and show both that (A.) words don't just correlate to objects (there are different kinds of words (§1-§45)), but also that (B.) it cannot be taken for granted what counts as the natural 'unit' of meaning. §46 onwards tackles this second aspect of Witty's objection to the Augustinian picture. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Also, if I'm right that the consideration of kinds of (uses of) words has dominated the discussion in the PI so far, it's even possible to broadly identify three successive sections of the book up to roughly §45, which correspond to extended discussions of three different kinds of uses of words:

§1-§27: Imperatives (block! slab!)

§28-§36: Demonstratives (this, that)

§37-§45: Names (Nothung, Mr. N.N.)

- each of which allows Witty to deepen his discussions of use, grammar, and illusions. The PI has alot more structural cohesion than it might seem on first glance. that said, perhaps worth noting that what follows in §46 onwards - the discussion of 'simples' and 'complexes' - breaks with this structure of discussion. Worth considering why. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Whoa, that looks at first glance like an aggressively Kantian reading of Wittgenstein. — John Doe

Hah, well, considering I read the PI as a Critique of Pure Language, I'm not exactly concealing my 'Kantian aggression' here. But it's important not to get too caught up in things here - I simply meant a paraphrase of this:

§24: "The word “language-game” is used here to emphasize the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life."

Which one can roughly read as: the meaning of words (or meaning in general) is determined/structured/conditioned/'grounded' (pick your poison) by the use to which it is put as part of an activity. Whether this in turn can be read as a question of 'conditions of possibility' is neither here nor there, and isn't really what I had in mind when invoking Kant (although I will say that, in line with Deleuze's reworking of the transcendental, if pushed, I'd say something like: Wittgenstein attends to the conditions of actuality of meaning, not to their possibility; this is why I've drawn connections, in a previous remark here, to the similarity of Wittgenstein's approach to the question of sufficient reason: why this meaning rather than that).

That aside, what I did have in mind when I made my Kant comment was their similarities with respect to their treatment of illusions. For Kant, it's the nature of reason itself which engenders 'transcendental illusions', illusions internal to the functioning of reason which are brought about by the 'illegitimate employment' of the faculties. For Wittgenstein, there are similarly illusions generated by the illegitimate employment of language itself, the confusion of kinds when 'language goes on holiday' and attention is not paid to the language-games or grammar to which uses of words belong.

A last comment: I make no bones about reading Wittgenstein as a fully-fledged philosopher with a strong and systematic understanding of meaning and language. I simply don't buy his self-characterisation as some kind of para-philosophical flâneur, flitting about making local points here and there. He has 'theories' like any other philosopher, and I think one needs to offer 'strong' readings of Wittgenstein in order to make sense of his work. My 'side-comments' linking issues in Wittgenstein to Kant, to Sellars, to questions of sufficient reason and so on are meant to place Witty directly in the fray of philosophy, situating him on eminently philosophical terrain which he probably wouldn't have liked, but then, I reckon his own writing betrays his self-image, in the best possible way, -

Naming and Necessity, reading group?It's funny. People are saying things like - how can one possibly imagine a world in which Nixon does not have such and such and did not do such and such???

One wants to say: tell me more about this person you can't tell me anything about. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.Instead he says a lot about how language structures our experience. — Πετροκότσυφας

Hmm, I can't say I really recognize this in Witty - how language structures meaning (which is in turn structured by our forms-of-life), yes, but experience? That doesn't really accord to my reading. But with respect to the question: 'what sort of thing is ontology'? - I agree that Witty enables a really interesting re-framing of this question, in much the same way Kant does. But the devil's in the details, and without going too much into it, I've already read Witty as a linguistic materalist par excellence. Maybe this will come out in the reading more as we go along. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.In a way, it's the opposite; language all the way down, a sort of linguistic idealism — Πετροκότσυφας

As in, that's the view you see Witty holding? -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.General remark: For me personally, probably the most powerful import of the PI is its provision of a critical apparatus from which one can evaluate mistaken uses of language. I’ve always maintained that the PI ought to be read as a ‘Critique of Pure Language’, which, similar to Kant’s project, is attuned to ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ employment of language, with illegitimate employment - the confusion of kinds of uses of words - leading to all sorts of what Kant calls ‘transcendental illusions’, and what Witty refers here to instances of language on holiday. The importance of the PI cannot be truly appreciated without an understanding of its critical-evaluative import: how it allows one to identify, or become far more sensitive to, problems of language use that might otherwise go unnoticed.

If I have one gripe, it is that Witty characterises philosophy as a whole as being nothing but the outcome of these processes of linguistic confusion. Contrary to Witty, I think that all philosophy worthy of the name has never been subject to this problem - in fact that philosophy has always been attentive to such issues in an implicit manner - and that his diagnosis of philosophy as suffering from such maladies is simply a misdiagnosis. Which doesn’t, of course, mean that the disease itself is misidentified - only misattributed. This doesn’t, I think, substantially impact the main results of the PI. -

Philosophical Investigations, reading it together.§37-§38

The discussion from §37 marks a new line in the progression of argument so far. Having, in §36, begun to broach the issue of being mislead by language (i.e. issues of ‘spirit’ and ‘superstition’), Witty will begin to flesh this out by comparing what we might call the logic of names with the logic of demonstratives (‘this’ and ‘that’). The issue once again hinges upon the different kinds of words that names and demonstratives are:

§38: "the word “name” serves to characterize many different, variously related, kinds of use of a word a but the kind of use that the word “this” has is not among them”.

This confusion between different kinds of words, when one kind is mistaken for another, is what happens, Witty famously says, when “language goes on holiday". Philosophical problems in particular, Witty avers, arise from just these kinds of confusions between kinds of (uses of) words. Here he speaks specifically on demonstratives mistaken for names:

§38: "For philosophical problems arise when language goes on holiday. And then we may indeed imagine naming to be some remarkable mental act, as it were the baptism of an object. And we can also say the word “this” to the object, as it were address the object as “this” - a strange use of this word, which perhaps occurs only when philosophizing”.

§39-§45

§39 till about §44 fleshes this out further, by trying to distinguish all the more rigorously between names and demonstratives. This happens by way of a discussion of how names don’t actually need a referent - or ‘bearer’, as Witty calls it - to be of use, that is, to have sense (italicised by Witty in §39). This is fairly straightforward so I won’t go into it, but the pay-off is in §45, where Witty definitively distinguishes names and demonstratives by noting that unlike names, demonstratives “can never be without a bearer”. The point of all of this is, again, to distinguish between different kinds of uses of words, which has been the common thread running through the entire book so far.

§43

§43 is easily one of the most famous and widely cited passages in the PI, so worth backtracking a little and devoting a remark to it. First, the passage itself:

§43: “For a large class of cases of the employment of the word “meaning” - though not for all - this word can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language. And the meaning of a name is sometimes explained by pointing to its bearer.”

One thing that jumps out at me is the context in which this passage appears: although often taken to be some kind of stand-alone mission statement about Witty’s overall views on language, in the context of the discussion, it actually serves to set-off the specificity of naming from language in general: naming is just one species of language use among others. This statement then, is inseparable from a consideration, again, of kinds of uses of words: to speak of a ‘use in the language’ (curious and significant employment of the definite article), is to speak of languages which employ different kinds of uses of words.

Streetlight

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum