-

Logic of truthAbsolutely. And Goodman goes on in the next paragraph (and the link in the first quote will take you there via page 49) to explain how he would eliminate talk of corresponding relations for n > 1. But let's stick to n = 1?

-

Logic of truthI mean one-place? (Sure I've seen "unary" quite a lot but I doubtless have it wrong.)

-

Logic of truthWhatever is meant by 'predicate' and 'property' there, you asked about model theory. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I assumed that by 'predicate' was meant primarily linguistic predicate or adjective, but that this corresponds roughly to a unary predicate in FOL? And properties are the corresponding unary relations?

But you wouldn't need to mention those? I mean, you did mention them, as is usual, and my proposed revision was clearly eccentric, in context. So I was pleased when you didn't immediately reject it. I'm ready to hear that model theory would require reference to corresponding properties, contra Goodman.

So I was interested (and still am) in what you have to say. -

Logic of truthI can't find a pdf, but here's the paragraph.

A second thread of Hochberg's article comes to something like this: a common predicate applies to several different things in virtue of a common property they possess. Now I doubt very much that Hochberg intends to deny that any two or more things have some property in common; thus for him as for the nominalist there are no two or more things such that application of a common predicate is precluded. Advocates of properties usually hold that sometimes more than one property may be common to exactly the same things; but Hochberg does not seem to be arging this point either. Rather, he seems to hold that a predicate applies initially to a property as its name, and then only derivatively to the things that have that property. The nominalist cancels out the property and treats the predicate as bearing a one-many relation directly to the several things it applies to or denotes. I cannot see that anything Hochberg says in any way discredits such a treatment or shows the need for positing properties as intervening entities. -

Logic of truthE.g.

The nominalist cancels out the property and treats the predicate as bearing a one-many relation directly to the several things it applies to or denotes. — Goodman, p49 -

Logic of truth

But no problem, either? Talk of properties when glossing use of a logical predicate is eliminable?

Even in model theory? -

Logic of truth'Snow is white' is true iff what 'snow' stands for has the property that 'white' stands for. — TonesInDeepFreeze

Would you (or Tarskian model theory) accept

'Snow is white' is true iff what 'snow' stands for hasthe property that'white' standsfor [it, among other things]. — TonesInDeepFreeze

? -

Interested in mentoring a finitist?I am talking about how the spectrum — apokrisis

I know, but as usual you don't see where I'm coming from.

that allows your 50 shades of grey — apokrisis

Yours not mine.

This is confusing for sure. — apokrisis

With that attitude...

But after the separation of the potential, you get the new thing of the possibility of a mixing. — apokrisis

...and with those abstract nouns.

So we start with a logical vagueness - an everythingness that is a nothingness. — apokrisis

Do you mean, an indiscriminate application of colour words to the domain of things (or patches)?

We have a “greyness” in that sense. Something that is neither the one nor the other. Not bright, not dark. Not anymore blackish than it is whitish. You define what It “is” by the failure of the PNC to apply. You are in a state of radical uncertainty about what to call it, other than a vague and uncertain potential to be a contextless “anything”. It is not even a mid-tone grey as there are no other greys to allow that discriminating claim.

But then you discover a crack in this symmetry. You notice that maybe it fluctuates in some minimal way. It is at times a little brighter or darker, a little whiter or blacker. Now you can start to separate. — apokrisis

Do you mean, you are able to apply the words in a manner that begins to distinguish two different though still overlapping colours?

You can extrapolate this slight initial difference towards two contrasting extremes. You can drag the two sides apart towards their two limiting poles that would be the purest white - as the least degree of contaminating black - and vice versa. — apokrisis

But you're anticipating the later refinement (the bipolar continuum) and assuming it's intrinsic to the earlier distinction. I was pointing out that it isn't.

Once reality is dichotomised in this fashion, then you can go back in and mix. You can create actual shades of grey by Goodman’s approach. — apokrisis

Goodman's approach is concrete and clear. Yours is abstract and poetic.

A discrete classification in no way has to imply a continuous one. -

Interested in mentoring a finitist?How do we recognise the discrete except to the degree it lacks continuity. — apokrisis

If it's not a rhetorical question (and apologies to the OP if this is off topic)...

The final requirement for a notational system is semantic finite differentiation; that is, for every two characters K and K' such that their compliance-classes are not identical, and every object h that does not comply with both, determination either that h does not comply with K or that h does not comply with K' must be theoretically possible. — Goodman, Languages of Art

So not necessarily a matter of degree. Arguably a matter of discrimination. Which can be all or nothing. Witness digital reproduction. Where black and white are kept safely apart by grey, and there is no need for any collapse (or refinement) into 50 or more shades.

(Easy with those abstract nouns please, Apo...) -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."A kettle is not a word. — Michael

Agree.

A kettle being black is not a sentence. — Michael

Agree, but want to know if "a kettle being black" refers to any combination of these

- the particular kettle indicated by context

- the particular black thing

- kettles in general

- black things in general

- black kettles in general

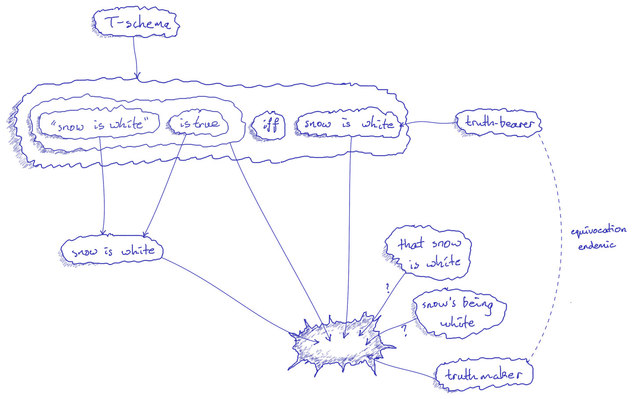

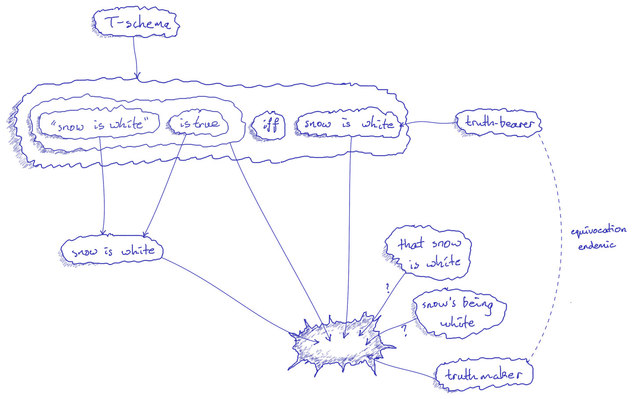

... which might elaborate picture 2. Or whether you allege, rather, an entity corresponding to the whole sentence "the kettle is black", as per picture 1. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Which would be helpful if using were anywhere near as clear as mentioning. — Srap Tasmaner

Yes, good point, for whole sentences. Not, though, for nouns or adjectives, where the distinction is perfectly clear: use a word or phrase to mention a thing, and use a name of the word or phrase to mention the word or phrase. Mention means refer to. Albeit with a hint of 'in passing'.

For whole sentences, the distinction is clear enough if clarity is desired. Either

Use a sentence to mention an alleged entity corresponding to the whole sentence. And whether or not you commit to the existence of the entity thus alleged, try not to equivocate between that and the sentence itself (mentioned by use of its name). (Picture 1.)

Or

Use a sentence to use one or more of its component parts to mention actual things or classes. (Picture 2.) Or to perform your preferred speech act to which the picture does no justice.

Either way, drop "fact" and "proposition" and "state", if clarity is your aim. Choose "sentence" or "abstract truth-maker" or "situation" or "thing". For as long as these remain somewhat less easily confused. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."

-

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."and we have a more substantial account of truth. — Michael

How isn't it just a more substantial account of p? -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Declarative sentences work by pointing a word or word-string at one or more objects. — bongo fury

Why is this at all un-obvious?

I suppose, because why would we need a sentence to point "white" at snow and not need another sentence to point "snow" at snow?

And, because perhaps we don't need a sentence to point "white" at snow. "White" already applies to what it applies to, and that happens to include snow. Otherwise the sentence wouldn't be true.

But we need a sentence to point out, highlight, the pointing or application of "white" to snow in particular, out of all the other things it applies to. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Is there something mysterious about correspondence? — Michael

For whole sentences, yes, a bit.

We have a sentence "the cat is on the mat", we have the cat on the mat, and we say that the former is about or describes the latter. Is that mysterious? — Michael

Yes, a bit, as soon as we notice that parts of the sentence taken separately are about or describe the cat on the mat.

"the cat" is about or describes the cat.

"the mat" is about or describes the mat.

"is on" is about or describes the notorious pair of objects.

Does it, or perhaps the whole sentence, be about or describe a relation? That could be mysterious and controversial. My objection to it, and to any supposed truth-making correlate of a whole sentence, even e.g. of (non-relational) "snow is white", is that it misunderstands how declarative sentences work, and further obscures the matter.

Declarative sentences work by pointing a component word or word-string at one or more objects. (Picture 2.) Thinking that the whole device points at a fact or state of affairs obscures the matter by suggesting that the fact has a similar structure to a sentence, or even a similar function. Perhaps we think the sentence is pointing at a pointing. Who knows what half-baked notions fly around, infecting believers and skeptics of correspondence alike. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."A propositional attitude is a mental state held by an agent toward a proposition. — Wikipedia

What would have been wrong with calling such an attitude a sentential attitude? And making it a mental state held by an agent toward a sentence?

A proposition would be no less such an attitude than belief, fear, assertion, doubt etc. The proposition that snow is white would be (e.g.) the proposal that "snow is white" be accepted, or that "snow is white" correspond to reality, or that "snow is white" be true etc.

Not solving much, of course, as such attitudes generally don't.

But folks might be less prone to confuse sentence with reality. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."True is what we call sentences which prevail: those whose tokens replicate successfully as free-standing (e.g. un-negated) assertions within the language.

What do you mean? — Bartricks

"True" is what we call sentence tokens that bear repeating on their own terms, which is to say, without contextualising in the manner of "... is untrue because..." or "... would be the case if not for..." etc.

Such contexts are potential predators, and must be fought off and dominated. -

Twin Earth conflates meaning and reference.I was confusing contextualized meaning and referent. — hypericin

And so was I, but deliberately. As per Goodman: https://fdocuments.in/document/goodman-likeness.html

Not necessarily as per Putnam, but I think it's arguable he is problematising non-extensional meanings. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."

Unlike redundancy theories, however, the prosentential theory does not take the truth predicate to be always eliminable without loss. What would be lost in (11′) is Mary’s acknowledgment that Bill had said something. — IEP

And that Mary agrees. And you have at least two speakers to deal with if you don't.

So

truth a property of sentences (which are linguistic entities in some language or other), — Pie

reduces further to a property of utterances. E.g.

Language (and even logic) as opinion polling. Which gets my vote, although it can sound daft. As can coherence theory in general, after all. -

Twin Earth conflates meaning and reference.S1: The water is cold.

General reference/meaning is indicated, specific not.

S2: ទឹកគឺត្រជាក់។

General not, specific not.

S3: The water in Lake Michigan is cold.

Both indicated.

S4: The water in Lake Michigan is ironic.

Specific reference/meaning is indicated, but general not: we are unable to infer the general application of both "water" and "ironic" in the event that they intersect.

General and specific can each be independently known or unknown. -

Twin Earth conflates meaning and reference.that S refers to a specific bit of water, not water in general. — hypericin

Yes, or as I put it: that you mean a specific bit of water, and we don't know which.

But, as you say, we all still know, as English speakers, what it means for the water (whichever it is) to be cold. Or, as I put it: we all understand your reference to cold things in general intersecting with water in general. -

Twin Earth conflates meaning and reference.Simply, we English speakers all know what S means. It is basic English. But we don't know to what it refers.

Therefore, meaning and reference are distinct concepts, and must not be conflated. — hypericin

I suggest they're interchangeable. We all know that your sentence S refers to water in general, and cold things in general. We just don't know which bit of water you mean. -

Twin Earth conflates meaning and reference.And yet, despite our clear understanding of S, we have no idea what the referent is. What water is cold? The relevant context is unknown. S has no clear referent and yet is perfectly understandable. This can only be the case if meaning and referent are different: only then can we make sense of understanding the one without knowing the other. — hypericin

So reference is to some particular item (e.g. glass of liquid), whereas meaning is reference to a wider class or extension (e.g. of water)?

We can refer to the wider extension (know the meaning of "water") without being able to refer to the particular item? Although wouldn't that (being so able) be knowing which item you meant? -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."We seem to agree that "snow is white" is a sentence — Banno

Yes if we agree to clarify that the string without quotes is what we're calling a sentence, while the string with quotes is a name facilitating talk about the smaller string (the calling it a sentence).

and that snow is white is a fact, — Banno

Yes if we agree to clarify that the string itself is not what we're calling a fact, at least, it is not the fact which, as a sentence, it represents. That would be as silly as confusing the name "Fido" with the dog which, as a name, it represents. The string is a sentence, representing or corresponding to the fact.

yet you seem to need to slip something else in between the bolded bit and the white snow. I don't. — Banno

If the bolded bit is the bolded string, and slipping something else in between that and the white snow is choosing to distinguish the two, I enthusiastically plead guilty. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."So meaning is both purely imaginary and not in the head, an imaginary lightning bolt from symbol to object — hypericin

Yep, why not?

... which is also the object? — hypericin

Eh?

Then how does he deal with sentences with no referent? "The cat in the hat" has meaning but no reference in the world. — hypericin

See the link above.

(For Goodman's solution. I'm not sure how Putnam deals with it. Good question. :smile: ) -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."the very same thing can be marks on a screen, a string of letters, a sentence and a fact. — Banno

Sure. Just not the fact which, as a sentence, it represents. Except of course in cases of self-reference: "this sentence has thirty one letters" etc.

The very same thing can be marks on a screen, a string of letters, a noun or noun phrase, and a thing. Just not the thing which, as a noun or noun-phrase, it represents. Except when it is "word" etc.

Now, I happen not to believe that there are such things as facts, which are represented (your word) by whole sentences, analogously to how such things as cats and dogs are represented by names or nouns. But I don't mind discussing or making a diagram about them. For the sake of argument.

You appear to be motivated by a similar scepticism, hence:

It's clear that the thing on the right is not the name of a fact. — Banno

Surely, a sentence doesn't work like a name? Agreed. Unfortunately you think you have a better idea, but you don't perceive that it involves equivocating, as is borne out by

the very same thing can be [generally, not just exceptionally] marks on a screen, a string of letters, a sentence and a fact [the one it also represents]. — Banno

So how did this happen?

"Snow is white" is not a fact; it is a sentence. That snow is white is how things are, and so, it is a fact.

Now the bit in the above sentence that I italicised is a string of letters, "snow is white", and it is not dissimilar to the bit I bolded. — Banno

Yes, but the bolded string and the italicised string both represent (allegedly) a non-linguistic fact. Only the slightly larger string that includes quote and unquote represents a string. So,

"Snow is white" is not a fact; it is a sentence. [But only the string without quotes is a sentence. The string with quotes is a name, facilitating talk about the sentence.] That snow is white is how things are, and so, it is a fact. [But only the fact represented by the string is how things are. The string is a sentence, talking about the fact.] — Banno

-

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Then where is it located? — hypericin

Wherever we pretend it to be located. In a diagram we might draw an arrow between our depiction of a symbol and our depiction of the corresponding object. We may or may not pretend some corresponding bolt of energy passes between the symbol and object themselves.

But I'm treating meaning as synonymous with reference, and I notice from your discussion with @Joshs that you baulk at that. I think Putnam points out a history of the supposed distinction, through denotation vs connotation, sense vs reference, and others more ancient. And recommends dropping it. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."And it seems that others (@Michael) have tried to make the same point to you. — Banno

I don't think so. @Michael grudgingly accepted the very same clarification you continue to reject. I don't know if this is because you also reject truth-makers corresponding to whole sentences. On which the clarification is premised. So do I. Maybe @Michael only accepts them for the sake of argument. So can I. And so you seemed to do here:

"Snow is white" is not a fact, because facts are things in the world, and so while "snow is white" represents a fact, it is not a fact. — Banno

So I used your word "represents" to clarify

The thing on the right is a fact. — Banno

as

The thing represented by the sentence on the right is a fact.

But whereas @Michael found this manner of clarification too obvious for words, you start critiquing correspondence theory:

It's clear that the thing on the right is not the name of a fact. — Banno

I wouldn't mind, if you wouldn't keep on equivocating between the factual literature on the right hand side of the T-schema and its worldly subject matter. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Meaning is not something in the world either, — hypericin

Agreed.

it is something in the head — hypericin

It is invented, or pretended, by people using their heads, but that doesn't locate it in the head.

(otherwise, how can we make sense of abstractions, lies, or fictions?). — hypericin

See the link above.

Sentence, meaning, worldly referent are all not identical, do you agree? — hypericin

The second is our pretended connection between the first and third. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Are scrawlings on a page or vibrations in the air true? — hypericin

Some of them are sentences, and some of those are true, yes. Meaning, some them are what we choose to point the word "sentence" at, and some of those are what we choose to also point the word "true" at.

Absurd, this is an obvious category error. They are symbols, only their interpretations can be true or false. — hypericin

What are interpretations? I would say: sentences that help us construe symbols as pointing at things. What would you say? -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."and meaning rests on definition — RussellA

I think the heap puzzle is a clear enough counterexample to that general assertion.

Meaning rests on, or is, usage: some of it agreed, some controversial. Whether 10 grains constitutes a heap is controversial. But a million grains is an obvious case. And obvious cases and obvious non-cases are sufficient to guide usage, for many words. We don't need a dictionary or manual.

The Sorites Paradox is only a paradox because it requires a definition that does not exist. — RussellA

If by definition you now mean threshold or cut-off point, then yes, and I agree. But then it's "only" a paradox because ordinary usage is perfectly meaningful without such definition. -

Logic of truthmetalanguage — Banno

I'm not sure, but: you mean object language? The interpretation is that fragment of the metalanguage that interprets terms of the object language? -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."A heap is defined as "a large number of". Large is defined as considerable. Considerable is defined as large. Definitions become circular. — RussellA

Yes, although the circularity perhaps only reflects the fact that definitions are unnecessary. The game asks for judgements, but not reasons.

I suggest that the brain's ability to fix a single name to something that is variable is fundamentally statistical. — RussellA

Fair enough. My interest is more in the linguistic community's ability to fix the name. Recent research in the area is indeed statistical.

Such statistically-based concepts could be readily programmed into a computer. — RussellA

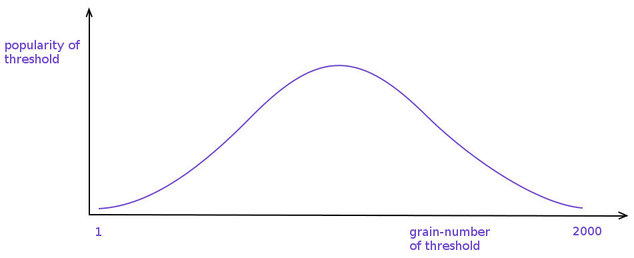

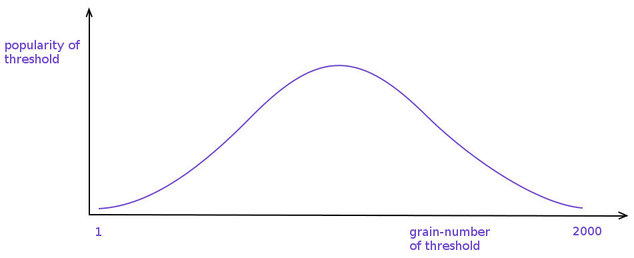

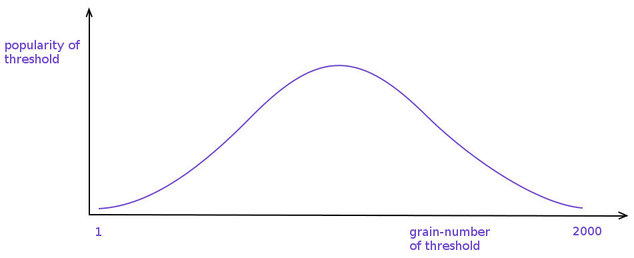

Or, even better, developed by evolutionary algorithms that simulate cooperative language games. The results are indeed similar to your picture, or mine here:

But, as such, they all fail the sorites test, which requires some perfectly absolute intolerance, as well as tolerance. Is my gripe. As discussed.

I mentioned this to you because you seemed to be wrestling with the tension between individual (Humpty Dumpty) judgements and general norms. And I think that's what the sorites puzzle is about. As your reply maybe supports. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."That should be obvious to any competent English speaker. Most of us understand the difference between use and mention. — Michael

I disagree. Never mind.

Perhaps the consequent of (b) is a fact, similar to how the subject of (a) is a person. — Michael

Well sure, but a consequent is a sentence (or proposition). So you now reject

I don't think it correct to say that the proposition is the fact. — Michael

as tiresome pedantry? Ok. Since you don't claim to be denying corresponding truth-makers for whole sentences, I shall be less suspicious of equivocation.

It is not a fact that snow is green. — Michael

Without truth-makers for whole sentences, this is unproblematic. It just means that " 'snow is green' is true" and "snow is green" share false instead of true as their common truth value.

And if you want more (rather than pure deflation) try

"True" applies to "snow is green" iff "green" applies to snow.

This talks about practices of classification.

c) unicorns are green

"True" applies to "unicorns are green" iff [more careful formulation, still false]

Fiction is literally false. Figurative truth translates usefully into literal truth about second-order extensions.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/556693 -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."I wouldn't say that the subject of the sentence corresponds to a person. — Michael

Well I would recommend it, in any discussion of semantics, as "subject" is notoriously ambiguous between word and object, and often clarified for example by use of "grammatical subject" versus "logical subject". (Which at least serves to flag up the issue.)

I mean exactly what I said; that snow being green isn't a sentence. — Michael

If you don't see how my clarification might prevent people from thinking you were talking about the word string "snow being green" not being a sentence, then I must suspect you are becoming enchanted by systematic equivocation. -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."Something else.

Snow being green isn't a sentence. Snow being white isn't a sentence. Vampires being immortal isn't a sentence. — Michael

Do you mean that some alleged (truth-making) non-word-string corresponding to or referred to by the word-string "snow being white", or indeed by the word-string "snow is white", isn't a sentence?

I think that was @Luke's point, but fair enough. So you would clarify thus:

Although there may be times, like with (a), where the consequentisdoes correspond to a fact, — Michael

?

Or are you still unsure whether it's correct to call a (truth-bearing) sentence or proposition a fact? -

"What is truth? said jesting Pilate; and would not stay for an answer."I'm unsure.

Snow being green isn't a sentence, so what is it? — Michael

Do you mean the word-string "snow being green" or something else? Are you unsure about that?

bongo fury

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum